Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

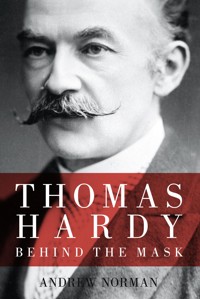

Thomas Hardy was shy to a fault. He surrounded his house, Max Gate, with a dense curtain of trees, shunned publicity and investigative reporters, and when visitors arrived unexpectedly he slipped quietly out of the back door in order to avoid them. Furthermore, following the death of his first wife Emma, he burnt, page by page, a book-length manuscript of hers entitled What I think of my husband, together with letters, notebooks, and diaries – both his and hers. This behaviour of Hardy's therefore begs the question: did he have something to hide, and if so, did this 'something' relate to his relationship with Emma? Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask pierces the veil of secrecy which Hardy deliberately drew over his life, to find out why his life was so filled with anguish, and to discover how this led to the creation of some of the finest novels and poems in the English language.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 395

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THOMAS HARDY

Other titles by the same author:

Tyneham: The Lost Village of Dorset (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2003)Sir Francis Drake: Behind the Pirate’s Mask (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2004)Dunshay: Reflections on a Dorset Manor House (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2004)Enid Blyton and her Enchantment with Dorset (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2005)Thomas Hardy: Christmas Carollings (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2005)Agatha Christie: The Finished Portrait (Stroud, The History Press, 2007)Mugabe: Teacher, Revolutionary, Tyrant (Stroud, The History Press, 2008)The Story of George Loveless and the Tolpuddle Martyrs (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2008)T.E. Lawrence: The Enigma Explained (Stroud, The History Press, 2008)Agatha Christie: The Pitkin Guide (Andover, Pitkin Publishing, 2009)Purbeck Personalities (Tiverton, Halsgrove, 2009)Arthur Conan Doyle: The Man Behind Sherlock Holmes (Stroud, The History Press, 2009)Father of the Blind: A Portrait of Sir Arthur Pearson (Stroud, The History Press, 2009)Jane Austen: An Unrequited Love (Stroud, The History Press, 2009)Hitler: Dictator or Puppet (Barnsley, Pen & Sword Books, 2011)

THOMAS HARDY

BEHIND THE MASK

ANDREW NORMAN

He slid apart

Who had thought her heart

His own, and not aboard

A bark, sea-bound …

That night they found

Between them lay a sword.

From the poem To a Sea Cliff by Thomas Hardy

First published 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Andrew Norman, 2011

The right of Andrew Norman to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6307 0

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6308 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Author’s Note

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Maps

Family Trees

1. Early Life: Influences

2. Religion: Love: Crime: Punishment

3. Emma: A Successful Author

4. Emma Inspires a Novel

5. Marriage

6. A Plethora of Novels

7. Dorchester: Max Gate

8. Jude the Obscure

9. Hardy Reveals Himself in Novels & Poems

10. Life Goes On

11. From Emma’s Standpoint

12. The Troubled Lives of the Giffords

13. The Death of Emma: An Outpouring of Poetry

14. Hidden Meanings

15. Florence Emily Hardy

16. Explaining the Poems

17. Declining Years

18. Aftermath

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Author’s Note

My interest in Thomas Hardy was aroused when I discovered a connection between my ancestors and the great Dorset novelist, poet and dramatist: that connection being the Moule family of Fordington.

Fordington, which lies on the outskirts of Dorchester – Dorset’s county town – is situated only 2 miles from Thomas Hardy’s family home at Higher Bockhampton. My paternal ancestors, who were yeoman farmers, lived here, and were baptised, married and buried at its parish church of St George, by the vicar, the Revd Henry Moule (1801–80). The Revd Moule’s son, Horatio Mosley Moule (known as Horace), was Hardy’s mentor and also his dearest friend.

Foreword

Thomas Hardy was an immensely shy person, who surrounded his house, Max Gate, Dorchester, with a dense curtain of trees, shunned publicity and investigative reporters, and when visitors arrived unexpectedly, slipped quietly out of the back door of his house in order to avoid them. So that no one should penetrate this mask of shyness, Hardy kept a rigid control over what aspects of his life were to be divulged and what were not. His first wife, Emma, behaved in a similar way, at least as far as her and her husband’s letters to one another were concerned: she burnt all that she could lay her hands upon.1 As for Hardy, following Emma’s death he burnt, page by page, a book-length manuscript of hers entitled What I Think of My Husband, together with most, but not all, of her diaries.2 When Hardy’s second wife, Florence, wrote a so-called ‘biography’ of him, he retained control by dictating to her virtually the whole of the manuscript. When Hardy himself died in 1928, Florence destroyed a great deal more of his and Emma’s personal papers.3 This begs the question, did Hardy have something to hide, a secret of some kind; and if so, is it possible, eight decades after his death, to discover what this secret was?

At first, this appears to be an impossible task, bearing in mind the vast quantity of ‘evidence’ which was deliberately destroyed by Hardy and his wives and others4 during their lifetimes. Also, when Florence died in 1937, her executor, Irene Cooper Willis, destroyed ‘a mass of the first Mrs Hardy’s incoming correspondence that had sat undisturbed in her former attic retreat at Max Gate ever since her own death twenty-five years earlier’.5 However, for a diligent researcher with an open mind, who is alive to the various clues to the conundrum which Hardy left behind, the task, as will shortly be seen, is not an impossible one.

For much of his adult life, Hardy laboured under a terrible burden of grief, the details of which he kept very much to himself. He required an outlet for this grief, a means of expressing his inner torment, and this outlet came through his writings. Hardy once told his friend, Edward Clodd, in respect of his novels, that ‘every superstition, custom, &c., described therein may be depended on as true records of the same – & not inventions of mine’.6 What he did not tell Clodd, and what only a very few of his contemporaries managed to discern, was the phenomenal extent to which his own personal life was reflected both in his novels and in his poems. However, even in this he was hamstrung, in that he could not afford to be explicit – at least while Emma was alive – for fear of offending her.

The purpose of this book is to pierce the veil of secrecy which Hardy deliberately drew over his life; to decipher the coded messages which his writings contain; to find out why his life was so filled with anguish, an anguish which led to the creation, by him, of some of the finest novels and poems in the English language. Only then is it possible to discover the real Hardy; the man that lies behind the mask.

The journey is a fascinating one. It leads to Hardy’s former haunts, including his family home at Higher Bockhampton (he disliked it being called a cottage, preferring it to be called a house); to St Juliot in Cornwall, where he met and courted Emma, and to Dorchester County Museum, where many important artefacts associated with him – including the contents of his study – are to be found. It also leads, surprisingly, to various mental hospitals, known in those days as ‘lunatic asylums’, located in such places as London, Oxford and Cornwall.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following:

Dr J. H. (Ian) Alexander; Elizabeth Boardman; Vanessa Bourguignon; Jane Bradley; Patricia Burdick; Mandy Caine; Brian Carpenter; Sue Cathcart; Kim Cooper; Caroline Cox; Helen Day; Mike Dowell; Dawn Dyer; Aidan Flood; Helen Gibson; Valerie Gill; Jennifer Hancock; Rachel Hancock; Pat Heron; Dr Jonathan Holmes; Vanda Inman; Renée Jackaman; Stephanie Jenkins; Basil Jose and family; Joanne Laing; Nuala LaVertue; Mark Lawrence; Hannah Lowery; Jasmine Metcalfe; Professor Michael Millgate; Jon Murden; Mike Nixon; Susan Old; Roy Overall; Eric H. Prior; Stephen Rench; Maureen Reynolds; Michael Richardson; Chris and Sally Searle (The Old Rectory, St Juliot, Boscastle, Cornwall); Reg Sheppard; Alan Simpson; Derick Skelly; Alison Spence; Judith Stinton; Lilian Swindall; Revd Robert S. Thewsey; David Thomas; Deborah Tritton; Toni Tuckwood; Jan Turner; Deborah Watson; David Williams; John Williams; Gwen Yarker.

Bodmin Town Museum; Bristol Reference Library; Bristol University Library: Special Collections; University of Bristol; The British Library; Colby Special Collections, Miller Library, Waterville, Maine, USA; Cornish Studies Library; Cornwall County Council; Cornwall Family History Society; Cornwall Record Office; Cornwall Studies Library; Dorchester Library; Dorset County Museum; Magdalene College, Cambridge; Oxfordshire Family History Society; Oxfordshire Health Archives; Oxfordshire Photographic Archive; Oxfordshire Record Office; Oxfordshire Studies Library; Oxfordshire Studies: Heritage & Arts; Plymouth Central Library; Plymouth and West Devon Record Office; Poole Central Library; Plymouth Central Library; Queens’ College, Cambridge; Redbridge Local Studies and Archives; Royal Geographical Society; Solicitors Regulation Authority; Thomas Hardy Society.

My thanks are also due to the Clarendon Press, Oxford; Cassell and Company Ltd, London; Mid-Northumberland Arts Group and Carcanet New Press; Oxford University Press; Macmillan Publishers Ltd; The Hogarth Press, London; David & Charles Ltd, London; MacGibbon & Kee, London; The Toucan Press, Guernsey; Longman Group Ltd; Colby College Press, Maine, USA.

A special mention is due to the enthusiastic and dedicated staff of the Cornwall Record Office, Devon Record Office, London Borough of Redbridge Local Studies and Archives, and Oxfordshire Health Archives.

I thank Professor Michael Millgate for his selfless generosity, and his diligence in preserving so much literature relating to Hardy which may well otherwise have been lost. I also thank my dear friend of many years, Dr Stuart C. Hannabuss, for his kindly words and valued criticism. And I am especially grateful, as always, to my beloved wife, Rachel, for her invaluable help and encouragement.

Maps

Bockhampton and district.

St Juliot and surrounding parishes.

North Cornwall.

Thomas Hardy’s ‘Wessex’.

Family Trees

Hardy Family Tree.

Thomas Hardy: Behind the Mask

Gifford Family Tree.

1

Early Life: Influences

Birth: Forebears

Thomas Hardy – the third generation of his family to bear that name – was born in a remote house in the hamlet of Higher Bockhampton in rural Dorset, on 2 June 1840. His entry into the world was an inauspicious one, and his life almost ended even before it had properly begun, for the infant Thomas was ‘thrown aside as dead’. ‘Dead! Stop a minute,’cried the monthly nurse (who attended the women of the district during their confinement). ‘He’s alive enough, sure!’ and she managed to revive the lifeless infant. Shortly afterwards, when he was sleeping in his cradle, his mother discovered ‘a large snake curled up upon his breast’ – which was also asleep. Because of its size, it may be deduced that this was probably a harmless grass snake rather than a poisonous adder, which is smaller.1 Thomas III, the subject of this book, was the firstborn of his family. The following year, 1841, his sister Mary arrived on the scene, but it would be another decade before brother Henry was born; to be followed by Katharine in 1856.

The Hardys firmly believed that they were descended from the more illustrious ‘le Hardy’ family of Jersey in the Channel Islands: John le Hardy having settled in Weymouth in the fifteenth century. They also believed that they were distantly related to Admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy, who served under Horatio Nelson as flag captain of HMS Victory in the Battle of Trafalgar. (As yet, no documentary evidence has been produced to substantiate these claims.)2

Thomas III’s family, on both sides, were hardworking and creative people, but their lives were not without incident. His paternal great-grandfather, John Hardy (born 1755), came from the village of Puddletown, 2 miles north-east of Higher Bockhampton, and 5 miles north-east of Dorchester. A mason, and later a master mason and employer of labour, John married Jane Knight and the couple had two sons: Thomas I (born 1778) and John.

Thomas I carried on the family tradition by adopting the same occupation as his father. At the age of 21, he ‘somewhat improvidently married’ a Mary Head from Berkshire; a person who had known great hardship as a child through being orphaned.3

Thomas I and his wife Mary had six children, the oldest being Thomas II (born 1811). Under Thomas II the family business flourished with as many as fifteen men in its employ, including the ‘tranter’ who transported the materials to the building sites.

Hardy’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Swetman of Melbury Osmond – a hamlet in north-west Dorset situated on the boundary of Lord Ilchester’s estate – was descended from a family of landed yeomen. She was of a romantic disposition, had an excellent memory and could be relied upon by the parson to identify, in cases of doubt, any particular grave in the churchyard. Also, she was skilled in ministering to the sick of the locality; her authority being the English herbalist Nicholas Culpepper’s (1616–54) Herbal and Dispensary.

When Elizabeth met and secretly married a servant, one George Hand, so great was her father John’s disapproval of the match that he disinherited her. This was to have grave consequences; for soon after her father’s death, Elizabeth’s husband also died, whereupon she and her seven children were left destitute. One of these children, Jemima, born at No 1, Barton Close, Melbury Osmond, in 1813, was destined to become the mother of Thomas Hardy III.

Jemima was skilled at tambouring (embroidering) gloves and mantua (gown) making; she worked as a servant and cook in several Dorset houses, and also in London. In late 1836 she became cook to the Revd Edward Murray, vicar of Stinsford’s parish church of St Michael (Stinsford being a hamlet situated less than a mile from Higher Bockhampton). On 22 December 1839 Jemima married Thomas Hardy II at her mother’s family’s church of St Osmond, at Melbury Osmond.

When she married Thomas II, Jemima was already more than three months pregnant. In those days, however, conception before marriage was considered by the Dorset farm labourers (and even by the lower middle classes) to be nothing unusual. In fact, among such folk, a marriage did not normally proceed until the pregnancy had become obvious. There was a good reason for this: it was considered essential for a woman to prove her ability to bear children, who from an early age would be required to help support the family. In nineteenth-century Dorset, children as young as 8 years of age were commonly put to work in the fields.4

Hardy’s Bockhampton Home

Even today it might prove difficult to negotiate one’s way through the host of labyrinthine lanes to Hardy’s former house, were it not for the fact that the route is adequately signposted. The house lies on the boundary of woodland and heathland, and may therefore be approached either from the woods or from the heath, or alternatively from a lane known as Cherry Alley. In Hardy’s time, Cherry Alley contained seven other houses, each one occupied by a person of some standing in the community. These occupants included ‘two retired military officers, one old navy lieutenant, a small farmer [presumably it was his farm which was small, rather than he himself] and tranter, a relieving officer and registrar, and an old militiaman, whose wife was the monthly nurse that assisted Thomas Hardy III into the world’.5

The Bockhampton house was a two-storey building with a thatched roof. It had been built in 1800–01 by Thomas III’s great-grandfather, John, for his son Thomas I and his wife Mary on land leased from the Kingston Maurward Estate. (In those days, a man with sufficient means could erect a dwelling for himself, or for a relative, and be thereafter permitted to live there for his lifetime; such a person being called a ‘livier’). Also included with the property were two gardens (one part orchard), a horse paddock, sand and gravel pits, and ‘like buildings’.6

The entrance to the house was through a porch leading directly into the kitchen, which had a deeply recessed fireplace on its south wall. Adjacent to this was the parlour, and then a small office where the three generations of Hardys – who were stonemasons-cum-builders – did their accounts and kept their money. Their workmen were handed their wages through a tiny barred window which was little more than a foot square and situated at the rear. From the office, an open staircase led up to the first floor which had two bedrooms. These upstairs rooms, being built into the eaves, had sloping ceilings and it was in the main bedroom situated above the office, that Thomas III was born.

The house had a chimney at each end and was thatched with wheat straw. The walls were made of cob (a composition of clay and straw), with a brick-facing at the front. The ground floor was paved with Portland-stone flagstones; the first floor with floorboards of chestnut 7in wide. Candles were used for lighting, as was usual in those times.

At some later date a self-contained bedroom and kitchen were added, the materials used being of inferior quality to those used in the construction of the original dwelling. It is likely that this extension was built some time around 1837 in order to provide accommodation for Thomas III’s grandmother, Mary Hardy (née Head), who in that year had been left a widow. (This would explain why Mary appears in the 1851 census as living in the parish of Stinsford, of which Higher Bockhampton was a part.) Later still, perhaps after Mary’s own death in 1857, the two buildings were conjoined.

Adjacent to the Hardy house was Thorncombe Wood, where swallet holes are to be found, together with a natural water feature, Rushy Pond. The wood is bisected by the Roman road linking Dorchester (Durnovaria, 2 miles distant) with London (Londinium) via Badbury Rings and Salisbury (Old Sarum), and also by an iron fence dating from the Victorian era and marking the boundary between two estates. On the periphery of the wood, on the south side, lies the hazel coppice; this species of tree being specifically grown for hurdle-making. Beyond the wood, the River Frome meanders through a fertile valley, with the distant ridge of the Purbeck Hills in the background. Ten miles to the south lies the town of Weymouth. Behind the house there extends a huge area of heathland, which in Thomas III’s time was dotted with isolated cottages. This was subsequently given the name ‘Egdon Heath’ by Hardy.

This was the landscape which Thomas III came to know in intimate detail, and also to love. It imprinted itself indelibly on his mind, and through him it would one day become familiar to people in all parts of the world, even though the vast majority of them had never seen it at first hand. During his lifetime, Hardy would live for a period outside of Dorset, but his beloved home county would never be far from his thoughts.

One of Thomas III’s favourite occupations was to lie on his back in the sun, cover his face with his straw hat and think ‘how useless he was’. He decided, based on his ‘experiences of the world so far … [that] he did not wish to grow up … to be a man, or to possess things, but to remain as he was, in the same spot, and to know no more people than he already knew’ – which was about half a dozen.7 In other words, he was perfectly happy and content.

At other times he would ‘go alone into the woods or on [to] the heath … with a telescope [and] stay peering into the distance by the half-hour …’ or in hot weather, lie ‘on a bank of thyme or camomile with the grasshoppers leaping over him’.8 When one cold winter’s day he discovered the body of a fieldfare in the garden, and picked it up and found it to be ‘as light as a feather’ and ‘all skin and bone’, The memory remained to haunt him. The death of this small bird revealed not only Hardy’s love of animals, but also his understanding of the frailty of life itself.9

Music: Books: School

Thomas Hardy III was born into a musical family and he himself developed a love of music and musicianship which remained with him all his life. His grandfather, Thomas I, in his early years at Puddletown, played the bass viol (cello) in the string choir of the village’s church of St Mary. He also assisted other choirs at a time when church music was traditionally produced by musicians occupying the raised ‘minstrels’ gallery’ at the end of the nave. Having married Mary Head, he moved into the house at Bockhampton, provided for him by his father. From that time onwards he attended the local thirteenth-century parish church of St Michael, situated a mile or so away at Stinsford, where he commenced as a chorister. He was also much in demand to perform at ‘weddings, christenings, and other feasts’.10

Thomas I was dismayed, on attending Stinsford Church, that the music there was provided not, as was the case at Puddletown, by a group of ‘minstrels’, but by ‘a solitary old man with an oboe’.11 With the help of its vicar, the Revd William Floyer, he therefore set about remedying the situation by gathering some like-minded instrumentalists together to play at the church. And from the year 1801, when he was aged 23, until his death in 1837, Thomas I himself conducted the church choir and played his bass viol at two services every Sunday.

At Christmastime there were further duties for the members of Stinsford’s church choir to perform, including the onerous task of making copies of those carols which had been selected to be played. On Christmas Eve it was the custom for the choir, composed of ‘mainly poor men and hungry’, to play at various houses in the parish, then return to the Hardys’ house at Bockhampton for supper, only to set out again at midnight to play at yet more houses.12

After his death in 1822, the Revd Floyer was succeeded by the Revd Edward Murray, who was himself an ‘ardent musician’ and violin player. Murray chose to live at Stinsford House instead of at the rectory, and here, Thomas Hardy I and his sons, Thomas II and James, together with their brother-in-law James Dart, practised their music with Murray on two or three occasions per week. Practice sessions were also held at the Hardys’ house. As mentioned, in late 1836, fourteen years after the arrival of the Revd Murray at Stinsford, Jemima Hand became Murray’s cook, and this is how she came to meet her husband-to-be Thomas Hardy II.

Thomas II is described as being devoted to sacred music as well as to the ‘mundane’, that is ‘country dance, hornpipe, and … waltz’. As for his wife Jemima, she loved to sing the songs of the times, including Isle of Beauty, Gaily the Troubadour, and so forth.13 However, although the family possessed a pianoforte and the children practised on it, she herself did not play.

A diagram was subsequently drawn by Thomas III, with the help of his father, of the relative positions occupied by the singers and musicians of the Stinsford church choir in its gallery in about the year 1835, five years prior to Thomas III's birth. At the rear were singers (‘counter’ – high alto), together with James Dart (counter violin). The middle row consisted of singers (tenor), Thomas Hardy II (tenor violin), James Hardy (treble violin) and singers (treble). In the front row were singers (bass), Thomas Hardy I (bass viol) and singers (treble). Finally, at the rear there were more singers, stationed beneath the arch of the church’s tower.14

What of the young Thomas Hardy III? He would never have the pleasure of meeting his grandfather and namesake, Thomas I, who died in 1837 – three years before he himself was born. Nevertheless, he inherited the family gift for making music and was said to be able to tune a violin from the time that he was ‘barely breeched’.15

When he was aged 4, Thomas III’s father gave him a toy concertina inscribed with his name and the date. Thomas III was said to have an ‘ecstatic temperament’ and music could have a profound effect on him. For example, of the numerous dance tunes played by his father of an evening, and ‘to which the boy danced a “pas seul” in the middle of the room’, there were always ‘three or four that always moved the child to tears’. They were Enrico, The Fairy Dance, Miss Macleod of Ayr and My Fancy Lad. Thomas III would later confess that ‘he danced on at these times to conceal his weeping’, and the fact that he was overcome by emotion in this way reveals just what an immensely sensitive and emotional person he was.16

As Thomas III grew older he learned, under the instruction of his father, to play the violin and soon, like his forefathers before him, was much in demand on this account. He always referred to the instrument as a ‘fiddle’, and to those who played it as ‘fiddlers’.17 It was the rule, laid down by his mother, that he must not accept any payment for his services. Nonetheless, he did on one occasion succumb to temptation, and with the ‘hatful of pennies’ collected, he purchased a volume entitled The Boys’ Own Book, of which his mother Jemima disapproved, since it was mainly devoted to the light-hearted subject of games.

Hardy’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Hand, was well-read and the possessor of her own library of thirty or so books (which was unusual for one who occupied a relatively low station in life). She was familiar with the writings of Joseph Addison, Sir Richard Steele, and others of the so-called ‘Spectator group’ (those who contributed to the Spectator magazine, founded in 1828): also with John Milton, Samuel Richardson and John Bunyan. The ten volumes of Henry Fielding’s works which she possessed would one day pass to her grandson, Thomas Hardy III.18

Elizabeth’s daughter, Jemima, inherited her mother’s love of books, together with a desire to read every one that she could lay her hands on. Under Jemima’s influence, therefore, it seemed inevitable that her own offspring, including the young Thomas III, would follow in her footsteps. And there were others, including Thomas III’s godfather, Mr King,19 who encouraged the boy in his reading; for example, by presenting him with a volume entitled The Rites and Worship of the Jews by Elise Giles, even though he had not, as yet, attained the age of 8.20 In fact, according to his sister Katharine, Thomas III had been able to read since the age of 3, and on Sundays, when the weather was considered too wet for him to attend church, it was his habit to don a tablecloth and read Morning Prayer while standing on a chair, and recite ‘a patchwork of sentences normally used by the vicar’.

Thomas III was considered by his parents to be a delicate child, and for this reason he was not sent to school until he was aged 8 (instead of 5, which was the normal practice). And so it was not until the year 1848 that he arrived at school for his first day of lessons. He was early, and he subsequently recalled awaiting, ‘tremulous and alone’, the arrival of the schoolmaster, the schoolmistress and his fellow pupils.

The Bockhampton National School, which had been newly opened in that same year, was situated a mile or so from his house, beside the lane which led from Higher to Lower Bockhampton. The school was the brainchild of Julia Augusta Martin, who, together with her husband Francis, owned the adjoining estate of Kingston Maurward. This they had purchased from the Pitt family three years earlier, in 1845. The couple inhabited the manor house, built in the early Georgian period, not to be confused with the estate’s other manor house nearby, which dated from mid-Tudor times. A benefactress of both Stinsford and Bockhampton, Julia had built and endowed the Bockhampton National School at her own expense; collaborating with the Revd Arthur Shirley (who in 1837 had succeeded the Revd Murray as vicar of Stinsford) on the project.

The Martins had no children of their own and Julia came to regard Thomas III as her surrogate child. In fact, she had singled him out as the object of her affection long before he had even started school. Passionately fond of ‘Tommy’, Julia was ‘accustomed to take [him] into her lap, and kiss [him] until he was quite a big child!’Thomas III, in turn, ‘was wont to make drawings of animals in water-colours for her, and to sing to her’. That he reciprocated Julia’s sentiments is borne out by his statement, made some years later, that she was ‘his earliest passion as a child’.21 One of Thomas III’s songs contained the words, ‘I’ve journeyed over many lands, I’ve sailed on every sea’,22 which would, no doubt, have amused Julia, who must have realised that Thomas III had never ventured beyond his native Dorset. It transpired, however, that the boy was shortly to widen his horizons when he and his mother Jemima paid a visit to her sister in Hertfordshire, and on the return journey caught the train from London’s Waterloo Station to Dorchester. This was Thomas III’s first experience of rail travel – the railway having come to Dorchester only as recently as the previous year, 1847.

At school, Thomas III excelled at arithmetic and geography, though his handwriting was said to be ‘indifferent’.23 Meanwhile, his mother encouraged him with the gift of John Dryden’s translation of Virgil, Dr Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas and a translation of St Pierre’s Paul and Virginia. A friend gave the young Thomas III the New Guide to the English Tongue by Thomas Dilworth24 and he also possessed A Concise History of Birds. Perhaps, however, his greatest joy was to discover, in a closet in his house, a magazine entitled A History of the (Napoleonic) Wars. 25 This would one day inspire him to write two books of his own, namely The Trumpet Major and The Dynasts.

When a year later, in 1849, Thomas III’s parents decided that their son should transfer to a day school in Dorchester, Julia Martin was offended, not only at the loss of her ‘especial protégé little Tommy’, but also because this new school was Nonconformist. This may have been a deliberate gesture of defiance by the Hardys who had developed a great antipathy towards Stinsford’s vicar, the Revd Shirley. This was because, as will shortly be seen, Shirley had been instrumental in destroying not only the fabric of their cherished medieval parish church of St Michael, but also its cherished tradition of providing live music for its congregation.

And so, at the age of 9, Thomas III commenced the second stage of his formal education, walking to and from his new school in Dorchester – a distance of 6 miles in total. Here he flourished, winning at the age of 14 his first prize: a book entitled Scenes and Adventures at Home and Abroad. 26 The headmaster, Isaac Last, was by repute ‘a good scholar and teacher of Latin’, but because this subject was not part of the normal curriculum, Thomas III’s father was obliged to pay extra for it. Nevertheless, his confidence in his son was amply rewarded when, in the following year, the boy was awarded Theodore Beza’s Latin Testament for his ‘progress in that tongue’.

Other authors with whom Thomas III was familiar were William Shakespeare, Walter Scott, Alexander Dumas, Harrison Ainsworth, James Grant and G.P.R. James.27 He also commenced French lessons, and at the age of 15 began to study German at home, using a periodical called The Popular Educator for the purpose. He was clearly a prodigious worker, and it is difficult to imagine that any other child in the county of Dorset (or anywhere else for that matter) was better read than he.

From whence did the impetus come that led Thomas III to drive himself so hard? From his father? Probably not, for Thomas III did not deny that the Dorset Hardys had ‘all the characteristics of an old family of spent social energies’, and it was the case that neither his father nor his grandfather had ever ‘cared to take advantage of the many worldly opportunities’ afforded them.28 Instead, the likelihood is that the drive came from his mother, the provider of books, who had insisted on him changing school in order to better himself; she, having experienced abject poverty as a child when her mother was left destitute, had no desire to see any child of hers in the same predicament.

Thomas III’s move to Dorchester was not without its repercussions. So annoyed was Julia Martin at having her protégé removed from her own school, that she forthwith deprived the boy’s father of all future building contracts connected with her Kingston Maurward Estate. Fortunately, Thomas II was able to obtain such contracts elsewhere, such as one for the renovation of Woodsford Castle – owned by the Earl of Ilchester and situated 5 miles to the east of Dorchester, by the River Frome.

When Thomas III subsequently met with Julia Martin, on the occasion of a harvest supper, she reproached him with having deserted her. Whereupon he assured her that he had not done so and would never do so. It would be more than a decade before the two saw one another again; by which time the Martins had sold their Kingston Maurward Estate and moved to London.

Domicilium

When he was aged 16, Thomas III composed a poem about his home entitled Domicilium, which reads as follows:

It faces west and round the back and sides

High beeches, bending, hang a veil of boughs,

And sweep against the roof. Wild honeysucks

Climb on the walls, and seem to sprout a wish

(If we may fancy wish of trees and plants)

To overtop the apple trees hard by.

Red roses, lilacs, variegated box

Are there in plenty, and such hardy flowers

As flourish best untrained. Adjoining these

Are herbs and esculents, and farther still

A field; then cottages with trees, and last

The distant hills and sky.

Behind, the scene is wilder. Heath and furze

Are everything that seems to grow and thrive

Upon the uneven ground. A stunted thorn

Stands here and there, indeed; and from a pit

An oak uprises, springing from a seed

Dropped by some bird a hundred years ago.

In days bygone –

Long gone – my father’s mother, who is now

Blest with the blest, would take me out to walk.

At such time I once inquired of her

How looked the spot when first she settled here.

The answer I remember. ‘Fifty years

Have passed since then, my child, and change has marked

The face of all things. Yonder garden plots

And orchards were uncultivated slopes

O’ergrown with bramble bushes, furze and thorn:

That road a narrow path shut in by ferns,

Which, almost trees, obscured the passer-by.

‘Our house stood quite alone, and those tall firs

And beeches were not planted. Snakes and efts29

Swarmed in the summer days, and nightly bats

Would fly about our bedroom. Heathcroppers

Lived on the hills, and were our only friends;

So wild it was when first we settled here.’

The poem is quoted in full, and for two reasons. Firstly, because it would be presumptuous of any person to believe that he or she was capable of describing the Hardys’ house better than Thomas III himself; and secondly, because it sheds important light upon his character.

From the poem it is clear that Thomas III possessed an excellent vocabulary, and was capable of writing with both style and fluency. He is poetical and knows how to make his words chime pleasantly with each other. He senses how, with the passing of time, everything changes. He also has a vivid imagination, where he sees the honeysuckle (‘honeysucks’) as having a will of its own, as it reaches upwards towards the sky. On a practical level, he has an extensive knowledge of local flora and fauna.

Surely Thomas III’s poem, Domicilium, is an indicator of the direction which his future life will take.

2

Religion: Love: Crime: Punishment

Thomas Hardy I died in 1837 which, as already mentioned, was the year in which the Revd Murray was replaced by the Revd Arthur Shirley as vicar of Stinsford. Shirley was a vigorous reformer and innovator who embraced the ideas of the High Church, as advocated by the leaders of the ‘Tractarian Movement’ (the aim of which was to assert the authority of the Anglican Church). This, for the Hardys, was no less than a disaster, and the ‘ecclesiastical changes’ which were imposed by the new vicar led Thomas Hardy II to abandon (in 1841 or 1842) all connection with the Stinsford string choir, in which he had played the bass viol, voluntarily, every Sunday for thirty-five years. Nevertheless, the Hardys continued to attend church every Sunday; the ‘Hardy’ pew being situated in the aisle adjacent to the north wall.

Nor did the rift between Shirley and Thomas II dissuade the latter’s son, Thomas III, from attending the Sunday School (established by Shirley) where, in due course, he became an instructor along with the vicar’s two sons. In this way he gained an extensive knowledge of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, and was said to know the morning and evening services by heart, as well as the rubrics and large portions of the psalms.1

There was a great deal of antipathy on the part of Anglicans towards Catholics at the time. This was apparent when Thomas II took his son to Dorchester’s Roman amphitheatre, Maumbury Rings, to see an effigy of the Pope, and of Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman (the first Archbishop of Westminster), being burnt during anti-Papist riots. As for Thomas III, despite the rigour and intensity of his Anglican upbringing, the age-old conundrum of religion was one which he would struggle with and agonise over throughout his life.

Quite apart from his infatuation with Julia Martin, and hers with him, Thomas III, like many people of artistic bent, was of a deeply romantic and impressionable disposition and likely to fall in love at any moment. However because of his natural shyness the objects of his desire were, as often as not, completely unaware of his lovelorn state. Such young ladies included one who passed him by on horseback in South Walk (one of Dorchester’s several tree-lined streets), and unaccountably smiled at him. Another was from Windsor; a third was the pretty daughter of the local gamekeeper who possessed a beautiful head of ‘bay-red’ hair – and was later to be recalled in his poem To Lisbie Brown. 2 Finally, there was Louisa, whom he recalled in another poem, To Louisa in the Lane. Thomas III would also immortalise the first romantic meeting of his own parents in his poem A Church Romance.

Doubtless the young man was destined one day for a great but more tangible romance. When it came, however, the question was, would it live up to his expectations?

Despite the seemingly idyllic and tranquil surroundings of the Hardys’ Bockhampton abode, woe betide anyone who dared to transgress the law or to flout the authorities; for if they did, harsh penalties awaited them. Thomas III’s fascination with hanging may have been the result of his father telling him that in his day he had seen four men hanged for setting fire to a hayrick, one of whom, a youth of 18, had not participated in the burnings but had merely been present at the scene. As the youth was underfed and therefore frail, the prison master had ordered weights to be tied to his feet in order to be sure that his neck would be broken by the noose. ‘Nothing my father ever said,’declared Thomas III, ‘drove the tragedy of life so deeply into my mind’ as this account of the unfortunate youth.3 Thomas II also told his son that when he was a boy and there was a hanging at Dorchester Prison, it was always carried out at 1 p.m. in case the incoming mail-coach subsequently brought notice of a reprieve of sentence. Another piece of information that Thomas III gleaned was that the notorious hangman, Jack Ketch, used to perform public whippings by the town’s water pump, using the cat-o’-nine-tails.

As a youth himself, Thomas III was to witness two executions. The first was of a woman, when he stood ‘close to the gallows’ at the entrance to Dorchester Gaol.4 The night before he had deliberately gone down to Hangman’s Cottage, situated at the bottom of the hill below the prison beside the River Frome, and peered through the window, where he observed the hangman inside as he ate a hearty supper.5 The woman to be hanged was Elizabeth Martha Brown, who paid the ultimate penalty for murdering her husband. ‘I remember what a fine figure she [Brown] showed against the sky as she hung in the misty rain,’ wrote Thomas III later, and ‘how the tight black silk gown set off her shape as she wheeled half-round & back [on the end of the rope]’ – an indication that perhaps the incident induced in him not revulsion, but a measure of sexual excitement.6

The second hanging occurred one summer morning two or three years later. Having heard that it was to take place, Thomas III took his telescope to a vantage point, focused the instrument on Dorchester’s prison, and as the clock struck eight, witnessed the public execution of another murderer, this time a male.

Again, images of these harrowing events made a permanent impression on the sensitive mind of the young Thomas III.

A Career: London: First Novel

Thomas III had been brought up to believe that his family was connected, albeit distantly, with other more illustrious ‘Hardy’ personages in the county – past and present – such as Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy, his namesake; Thomas Hardy, who had endowed Dorchester’s grammar school in Elizabethan times; and several others including, of course, the Channel Island Hardys and in particular one Clement le Hardy, Baillie of Jersey. From this it may be inferred that his family was desperately anxious for the young Thomas III to succeed in the world and make something of himself; to reverse what was seen as the trend, in their case, of a family in decline. However, before he embarked upon the journey of life, his mother Jemima issued him with a warning. Said he, it was ‘Mother’s notion (and also mine) that a figure stands in our van [path] with arm uplifted, to knock us back from any pleasant prospect we indulge in’.7

While Thomas II was working on the Earl of Ilchester’s Woodford Castle, it so happened that an associate of his, one John Hicks, architect and church restorer, was present there with him. Thomas II duly introduced Hicks to his son Thomas III – who also happened to be present on the day – and on the strength of this meeting Hicks invited Thomas III to assist him in a survey. Hicks liked what he saw, and the outcome was that he invited Thomas III to be his pupil. Thomas II duly agreed to pay Hicks the sum of £40 for his son to undergo a three-year course of architectural drawing and surveying. So, in 1856, when he was aged 16, the young Thomas started work at Hicks’ office in Dorchester’s South Street.

By now, Thomas III had progressed from the frailness and fragility of his childhood into a vigorous manhood. He threw himself with gusto into his new apprenticeship, but at the same time, this did not prevent him from pursuing his study of the Latin language, which enabled him to read the New Testament, Horace, Ovid and Virgil in the original. Likewise, by teaching himself Greek, he was able to read Homer’s epic poem Iliad. This necessitated him rising at 5 a.m., or 4 a.m. in the summer months, in order to fit everything into the day. Hicks, being a classical scholar himself, was well-disposed to Thomas III’s efforts in this respect.

With fellow-pupil Robert Bastow and two other youths – both recent graduates of Aberdeen University, who were the sons of Frederick Perkins, Dorchester’s Baptist minister – Thomas III had furious arguments as to the merits and de-merits of ‘Paedo-Baptism’ (the baptism of infants). This led the latter to consider whether, having himself been baptised as an infant at Stinsford’s church of St Michael, he should now be re-baptised as an adult.

Adjacent to Hicks’ office in South Street was the school of poet and philologist William Barnes, who would often be called upon to adjudicate in matters of dispute between Thomas III and Bastow on the subject of classical grammar. Barnes, a Latin and oriental scholar of great distinction, had compiled A Philological Grammar in which more than sixty languages were compared.

The year is 1859 and Thomas III (who henceforth will be called Hardy) is aged 19. His three-year apprenticeship is over and he is now given the task, by Hicks, of making surveys of churches with a view to their ‘restoration’. In reality, this was a euphemism for what Hardy regarded as ‘ruination’, and the fact that he had become a participant (albeit unwilling) in this process would, in later years, cause him enormous regret. Its legacy remains to this day and is easily borne out by a comparison of, say, the ‘restored’ Stinsford church of St Michael and Puddletown’s church of St Mary, which escaped restoration and in consequence has retained its exquisite and fascinating historical artefacts in their original condition and situation.

The restoration of Stinsford church had begun under the aegis of the Revd Shirley in 1843, when the main part of the west (‘minstrels’) gallery was removed. Shirley also removed the chancel pews and replaced the string choir with a barrel organ. For this, the Hardy family never forgave him. Hardy would one day get his revenge (although these traumatic events had occurred when he was a mere infant) in a poem, The Choirmaster’s Burial, in which ‘an unsympathetic vicar forbids [deceased choirmaster] William Dewey old-fashioned grave-side musical rites’.8

Hardy was now at a crossroads: the question being whether he should pursue a career in architecture or immerse himself ever more deeply in the Classics, and in particular, the Greek plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles. In this, he was to be guided by his literary friend and mentor Horace Moule, son of the Revd Henry Moule, vicar of nearby Fordington. Born in 1832 and therefore eight years his senior, Horace Moule had studied at both Oxford and Cambridge universities and had recently commenced work as an author and reviewer. It was he who introduced Hardy to the Saturday Review – a radical London weekly publication which attributed the majority of social evils to social inequality – and who also made Hardy gifts of books, including Johann Goethe’s Faust.

Hardy now commenced writing, in the hope of being published. He was successful, and his first article, an anonymous account of the disappearance of the clock from the almshouse in Dorchester’s South Street, appeared in a Dorchester newspaper. The poem Domicilium followed, together with articles published by the Dorset Chronicle