13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

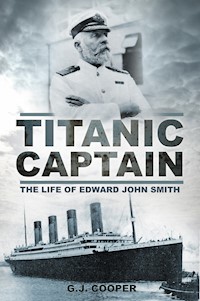

Commander Edward John Smith's career had been a remarkable example of how a man from a humble background could get far in the world. Born to a working-class family in the landlocked Staffordshire Potteries, he went to sea at the age of 17 and rose rapidly through the ranks of the merchant navy, serving first in sailing vessels and later in the new steamships of the White Star Line. By 1912, he as White Star's senior commander and regarded by many in the shipping world as the 'millionaire's captain'. In 1912, Smith was given command of the new RMS Titanic for her maiden voyage, but what should have been among the crowning moments of his long career at sea turned rapidly into a nightmare following Titanic's collision with an iceberg. In a matter of hours the supposedly unsinkable ship sank, taking over 1,500 people with her, including Captain Smith.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

To my parents William and Barbara Cooperand in memory of my uncle Peter Tomkinson,the first historian in the family.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It would have been difficult if not impossible to have written this book without the interest and assistance of a number of institutions and individuals. The author would therefore like to start by thanking the staff of the following establishments: the Maritime History Archive at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada; the National Archives, Kew, London; the Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool; the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; the New Brunswick Museum, St John, New Brunswick, Canada; Paris Smith LLP, formerly Paris, Smith and Randall, solicitors, Southampton; the University of Keele Library; Hanley Central Library and Archives; Liverpool Library; Lichfield Library.

The list of private individuals I wish to thank begins with Ernie and Pauline Luck who have pretty much been my co-conspirators in this work. Ernie introduced me to Captain Smith’s family link with the Mason and Spode pottery dynasties, then went out of his way to trace the exact address of the house that Smith was born in and the credit remains with him for that. Both Ernie and Pauline also proofread a number of my chapters and prevented a few of my barbarisms getting into print. Via Ernie I would also like to thank a number of other people whose information contributed to this biography: the late Marjorie Burrett; Lyane Kendall; and Barbara Faruggio. I would also like to thank the members of the Mason’s Pottery Collectors Club for allowing me to give a talk on Captain Smith and for the many kind comments I received afterwards.

Another person who has my sincerest thanks is Norma Williamson, a descendant of Captain Smith’s uncle George. Her research into her family history came as a pleasant revelation saving me a great deal of legwork and filling in a few otherwise embarrassingly large blanks in the Smith family tree.

Other individuals I wish to thank are: my friend and work colleague Paula Brown, who proofread several of my chapters and brought a number of points to my attention; Martin Biddle who helped me out of a number of geneaological holes; Steve and Gill Jones who provided me with the location of the grave of Smith’s mother and were good enough to send me some photos; Susan M. Wickham who put me onto Kate Douglas-Wiggin’s memoirs; and in a very useful info swap, novellist Ann Victoria Roberts and her husband Captain Peter Roberts, master of the heritage steamship Shieldhall, pointed out a number of researcher’s and landsman’s errors in my work that I had not noticed. G.W. Robinson, Geoffrey Dunster RD, RNR, and Lt. Commander Raymond J. Davies RD, RNR, contributed useful information to my earlier research and deserve to be thanked here still. So too does Jeff Kent, who many moons ago published my first book on Captain Smith. Two other individuals I would like to thank (though they may both have long since forgotten about me) are Biddie Garvin, who in 1987 during a college trip to Stratford to see a production of The Taming of the Shrew, gave me the idea for my first book on Smith and started me on this path; and Mike Disch, an American actor who in 2003 contacted me out of the blue for any insights I might have into Smith and rekindled interest in what for me had by that time become a rather dusty subject.

One major difference between this work and my original research, is that the online community has provided me with a wealth of research and opinions to draw upon, most notably on Philip Hind’s excellent Encyclopedia Titanica website. Though I have by no means corresponded with all of the individuals listed here, to paraphrase Lightoller somewhat, their online comments, knowledge and good common sense in the face of much Titanic-related silliness has given me much guidance and food for thought and it would be churlish not to acknowledge the fact. I should note, though, that any opinions expressed in this work, are mine and mine alone. I would, therefore, like to thank, in no particular order: Inger Shiel, Mark Chirnside, Michael H. Standart, Erik Wood, Dave Gittens, David G. Brown, Bob Godfrey, Brian J. Ticehurst, Bill Wormstedt, Tad Fitch, George Behe, Addison Hart, Scott Blair, Samuel Halpern, Senan Molony, and Randy Bryan Bigham. Dustin Kaczmarczyk of the German Titanic Society contacted me privately pointing out a number of problems with my original text that needed addressing and has my thanks for that. Mark Baber, along with his many contributions to the Titanica site, also very kindly provided me with the fruits of his research showing that Captain Smith had been unfairly blamed for the grounding of the SS Coptic in 1889. Another community member, Parks Stephenson was good enough to contact me with information on the installation of Marconi wirelesses on White Star vessels, for which he too has my thanks. I have no doubt there are others, but it is difficult to recall everyone and should I have obviously missed anyone out they have my apologies.

Last, but by no means least, I would like to thank my family and friends who, without badgering me too much over the years, have continued to be interested in the progress of my research.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

1Made in the Potteries

2Before the Mast

3White Star

4The Majestic Years

5Baltic and Adriatic

6The Wednesday Ship

7Titanic

8Nemesis

9Momento Mori

10Epilogue

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

1

MADE IN THE POTTERIES

Hanley in North Staffordshire, where Edward John Smith, the future captain of the Titanic, was born in 1850 was one of six towns that by the time of his birth were known collectively as the Potteries. Only two centuries before, the district had not existed. Hanley and its near neighbours, Tunstall, Burslem, Stoke, Fenton and Longton, had still been a group of small moorland farming settlements, but the heavy upland soil and higher than average rainfall made for poor farming and circumstances had obliged the inhabitants to indulge in supplementary crafts to make ends meet. The local abundance of clay and coal had made pottery-making the natural choice in this respect and over time the locals had earned a reputation for the production of a wide range of domestic wares and pottery storage jars that were sold at the larger county markets. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution during the eighteenth century, these village crafts rapidly blossomed into full-blown industries and the small settlements had grown as people flooded into the area looking for work. So successful had the subsequent rise of the area been, that by the middle of the eighteenth century the six towns of the Potteries supplied the bulk of the pottery used in Britain and by the beginning of the nineteenth century the area was well on the way to dominating the world’s ceramic market.

Success, though, had come at a heavy price. As photographs of the Potteries in the nineteenth century reveal, 100 years of industry had produced a grim urban landscape and visitors to the area met with an interesting, if rather apocalyptic scene. When a German traveller, Johann Georg Kohl, first saw the district in about 1843, he was put in mind of an embattled line of fortifications. On approaching the Potteries from Newcastle-under-Lyme, the first thing he noticed was the thick cloud of smoke that spread out over the region. This poured from hundreds of factory chimneys and bottle ovens – the distinctively shaped pottery kilns of the region – of which dozens were often gathered close together looking, Kohl noted, ‘like colossal bomb-mortars’ in the distance. The conical slag heaps of the local collieries, the high roofs of the drying-houses and warehouses and the thick walls that enclosed the factories, along with the piles of clay, coal, flint, bones, cinders and other matters lying scattered about, served only to strengthen the illusion. Nor did the Potteries diminish in interest as he passed its borders. In the sooty cobbled streets between the great factories, or pot banks as they are known locally, he spotted the small terraced houses of the workers, the shopkeepers, the painters, the engravers, the colourmen, and others, while here and there the intervals were filled up by churches and chapels, or by the grander houses of those who had grown rich as a result of the pottery industry.1

Sprawled across the south-western slope of a gently rising hill, Hanley lay roughly in the centre of the Potteries conurbation. With a population of just over 25,000 people in 1851, it was the largest of the six towns. Like its neighbours, its inhabitants were largely employed in the pottery industry or down the local pits. The bulk of the town’s pot banks, though, were situated away from the town centre and Hanley had developed into the commercial heart of the region. Perhaps because of this, even today Hanley town centre – now the city centre of Stoke-on-Trent – still largely retains its eighteenth-century street plan, relatively unaltered by later developments; its winding streets, scattered squares and ‘banks’ forming an ‘archipelago of island sites’, as the VictoriaHistory has described the seemingly random knot of buildings at its core. The majority of the old village buildings had been demolished before E.J. Smith was born and had been replaced with much more imposing structures. A small, stone-built covered meat market – now the Tontines – was built in 1831, while a new town hall complete with columns and a classical pediment was erected in Fountain Square in 1845. Until the late 1840s, Market Square had been dominated by a large coaching inn, the old Swan Inn, but this too had been demolished and replaced with a new market hall which opened in 1849. This market was the grandest structure of all, with an impressive stone façade three storeys high with balustrades and a row of ornamental stone vases set above a row of tall shop windows. These shops were probably the first of Hanley’s more ambitious shop fronts, ‘far above the standard of everything else in the Pottery district’, and they quickly became the focal point of the town.2

Houses were being built too, hundreds of them. A sudden influx of newcomers into the town in the late 1840s and 1850s – not only pottery workers, but also new workers for Lord Granville’s collieries – had caused serious overcrowding in the available housing in the lower part of town and in Shelton. This had created further problems with serious outbreaks of disease that caused much death and misery. In response, new housing sprang up in previously underpopulated areas, such as Northwood, Far Green and Birches Head. Another major development, and one more pertinent to our story, occurred to the east of the main town, where what became the Wellington estate started to expand from Well Street where Captain Smith was born, down over the other side of the hill across previously untouched farmers’ fields.

Well Street

Just as the older buildings were giving way to grander structures, so too were the colloquial street names of yesteryear being exchanged for more glorious titles. As the name of the new Wellington estate implied, many of its streets would be named after famous men or events associated with the Napoleonic Wars – Wellington Road, Nelson Place, Picton Street, Waterloo Street and Eagle Street. The names of the older streets, though, situated on the edge of the old village were more parochial in style and Well Street was one of these. It predated the new estate and was so named because it was the site of, or was situated near to, two old wells. One of these, the Woodwall well, had been the main source of water for the entire town in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By the 1840s, it was accessed via a street pump from which the local housewives drew water for their household needs and a water cart run by a ‘higgler’ filled up. This higgler then drove his cart around the town selling his water for ½d a bucketful. Today it seems primitive, but at the time it was a valuable and useful trade, for in the early years of the nineteenth century piped water was still a rarity and often of an inferior quality to this natural spring water. Because of this, the Woodwall well and other natural springs were still regularly used as late as the 1840s and even though the supply of water had grown limited due to the flow being diverted on many of its underground streams, there are indications that it may still have been used by people in the neighbouring streets as late as the 1850s. Even today these ancient springs still flow, though the waters of the Woodwall well now run through a conduit that empties into the nearby Caldon Canal.

Well Street also still exists, but like the wells it was named for it is not what it once was. In the not so distant past the street was much longer and like nearby Charles Street, reached up to Bucknall New Road. In the 1960s, the upper part of the street was demolished and the space given over to the construction of a series of maisonettes and blocks of flats. What remained also survived the construction of the modern bypass known as the Potteries Way, the building of which, in the 1980s, removed several old streets from the map. Modern houses have replaced the old Victorian houses down one side of what remains of Well Street. Down the other side there still exists a row of old Victorian terraced houses that run down the bank from number 51, to the Rising Sun pub at the junction with Waterloo Street. In these we may fancy that we catch a glimpse of what Well Street once looked like, but only in late Victorian times, for it seems that most of these houses did not exist until after 1891 and although a Rising Sun pub had been on the site for years, the present building did not appear until 1886.

To see Well Street how it was prior to this, we need an old map and a little imagination. The map is extant. Produced in 1865, the large-scale map of the Potteries, surveyed by Captain E.R. James RE, clearly shows the layout of the upper part of the Wellington housing estate that year. It was probably a typical street of the locality and the period, with a simple dirt track, or a cambered cobbled road with blue brick pavements. The upper part of Well Street was given over to the terraced houses that Kohl had noted on his peregrination, the monotony of which was broken by the occasional shops that were simply houses converted by their owners. Most of the terraced houses in Hanley were built back-to-back with small yards to each, containing ash pits and privies. The houses were built of brick with tiled roofs and most had only four rooms. The ground floor was paved with bricks or quarries, there was a front parlour and behind it a living room with a cooking range and possibly a boiler for washing clothes in, while the upper storey had two bedrooms.

Of course, the conditions inside each home varied with the wealth, social background and disposition of the occupants. One visitor to the area noted some workers’ houses, the windows of which were decked with flowers in pots that would put London parlours to shame.3 These pots were often placed on mahogany chests of drawers which were themselves clear indications of some small wealth. On the other hand, an article in the MorningChronicle spoke of grimy parlours containing wretched sofas, all rickety boards and dirty calico that served as beds for some members of the family. An official report into the state of large towns in the region noted that though small and gloomy, the houses locally were not deficient in ventilation, but the inhabitants being for the most part engaged in warm manufactries were mortally afraid of cold air and the illnesses it might engender and blocked most of the vents and gaps. 4

The lower half of Well Street, though, would have come as a pleasant surprise to anyone expecting a continuation of these typical working-class dwellings. Clearly marked on James’ map, three quarters of the way down the now steeply inclined bank and set back from the road, was a large property of quality fronted by an ornamental garden. This was ‘The Cottage’, a large house owned by George Fourdrinier, a local paper manufacturer who had made his fortune producing paper transfers for the pottery industry. The quality of his establishment can be gauged from the details in the sales advertisement for the property carried in the first copy of the StaffordshireSentinel of 7 January 1854, following Mr Fourdrinier’s retirement to Rugeley just prior to his death. There were dining rooms, a drawing room, a breakfast room, four bedrooms, a kitchen and school rooms. Included in the household goods up for sale over the four days 16 to 19 January 1854 were: a mahogany bagatelle board, a pair of globes, a solar lamp, a magnificent fourteen-day Parisian timepiece, an eight-light chandelier, a six and a half-octave pianoforte by Collard and Collard, a collection of oil paintings by eminent masters, 100 volumes of books and electroplated tea and coffee sets. The list moved on to more mundane items, but also listed a six-year-old carriage horse (16½ hands) and a ‘useful bay horse’. These could be harnessed into either the ‘Capital, well-built four wheel Dog Cart’ or the ‘handsome Barouche, with turn over back seat, in good condition.’ 5

For the people of Well Street, the main benefit provided by The Cottage would have been the large ornamental garden in front of it, its numerous trees and bushes adding a splash of colour to the soot-stained bricks and cobbles of the neighbouring houses. These gardens stood on land now occupied by the remaining terraced houses of Well Street. The garden is clearly depicted on James’ 1865 map, showing that The Cottage was still occupied years later and proving that many if not all the houses there today are later additions.

The presence of such a high-class house also alters somewhat the perception of Well Street as the largely working-class street that it later became. We are instead looking at an area in transition, if The Cottage predated most of the surrounding terraces. After all, prior to the start of construction of the Wellington estate, Well Street was on the rural edge of the village, the perfect place for a rich manufacturer to make his home. The construction of the Wellington estate began in the 1830s and the church of St Luke’s, which on James’ map can be seen just to the east of The Cottage, was not built until 1853–54. Fields to the west of Well Street, where Gilman Street now stands, plus others further to the east, support this idea. Also many of the back yards to those houses down the western side of Well Street even appear to have had trees in them. So, though not perhaps a rural idyll, Well Street was on the other hand not a blighted urban slum. Nature still had its place. It seems to have been a good spot to settle and raise a family.

The Smith Family

One couple that did just that were Captain Smith’s grandparents, Edward and Elizabeth Smith, who arrived in Hanley in the early years of the nineteenth century. For the next sixty or perhaps seventy years, three generations of their family lived there, raising their children and, in the case of E.J. Smith’s branch of the family, rising in social status. Edward Smith first appears in Well Street as an apparently humble working-class tenant, but when the last of the family finally quit the street and the Potteries in the late 1870s, they were lease holders on at least two properties.

A little is known about the life of Edward Smith senior. He was the son of Edward Smith and Jane Blakemore who had married in Bradley, near Stafford, on 27 December 1760. They seem to have had a number of children, their son Edward being born on 16 April 1775 and baptised at St Mary’s Church, Stafford, on 21 May that year. Twenty-three years later on 10 September 1798, at Ranton parish church, the younger Edward married twenty-year-old Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Tams, the daughter of John and Catherine Tams from the village of Salt. The couple may have settled locally at first, but by the early 1800s, drawn perhaps by the promise of better wages and greater opportunities, they had moved north to the Potteries where they settled in Well Street. Here, Edward started working as a potter.

In 1807, the first appearance of the name Edward Smith can be found amongst hundreds of other mundane entries in the 1807–08 Hanley Rate Book. There are no street names or house numbers given in this large red tome and the most that can be gleaned from the book is that one Edward Smith occupied property No.4375, owned by a certain William Tambs; the rate on the house was 2s 4d. As there are no remaining rate books for the years 1808–62, it is impossible to trace this particular Edward Smith any further. However, in 1818 an early trade directory of the Staffordshire Potteries was published, which proved to be more informative. In the section covering Hanley, we find the following entry: ‘Smith, Edward, potter, 8 Well Street, Old Hall Street.’ The presence five doors away of Samuel Sneyd, grocer at number 3 Well Street, indicates that this was indeed Captain Smith’s grandfather. Mr Sneyd and Edward Smith’s family were in the same houses relative to one another, at the time of the 1841 census.6

Between 1807 and 1822, at least seven children were born in Hanley whose parents were named Edward and Elizabeth Smith. The eldest of these, Edward, was baptised on 10 May 1807, while Mary Ann (or Mary Anne) is listed as being baptised twice, on either 10 or 28 May 1809. One Thomas Smith was baptised on 30 October 1814, Jane on 11 September 1816, William on 1 June 1818, and Phyllis was baptised on 16 September 1821. All of these children had been christened at St John’s, the town’s Anglican church, but the last child, George, was baptised at the Charles Street Wesleyan Chapel. His details are more complete; he was born on 28 October 1822 and baptised on 1 December 1822.7 Although the double entry for Mary Ann Smith raises some questions, the chances are very good that this is a full list of Edward and Elizabeth Smith’s children. There is supporting evidence that Edward and George, the eldest and the youngest, were related, as they were both still living with their mother in 1841 when the census was taken. We also know that Jane Smith was their sister, as Edward would be a witness at her wedding and her daughter was lodging with his family in 1861.

From the information contained in the 1851 and 1861 census returns, it seems that Edward Smith junior, the father of Edward John Smith, was actually born in 1805, two years before the St John’s baptism. That he received some education in his youth can be seen from the fact that he was able to write his name in a strong and practised hand when he later married. What form this education took is unknown, but from 1805 to 1817, when the building was demolished, a Sunday school for local boys operated in Hanley’s old market hall, a small, ugly brick building supported on iron pillars, which stood at the top of the present-day Market Square. His schooling, though, would have been a very perfunctory affair, lasting at best only a few years, for by his early teens, Edward, like hundreds of other youngsters across the district, was apprenticed as a potter.

To most people the term ‘potter’ conjures up an image of a man sitting at a potter’s wheel throwing finished wares. In Stoke-on-Trent, however, ‘potter’ is very much a generic term covering a dozen or more occupations on a pot bank. What evidence there is, namely a single reference on his death certificate, indicates that Edward had actually worked as a pottery presser, pressing clay into plaster moulds to form the shape of the pot. Though not as skilled a job as throwing, pressing nevertheless requires speed, dexterity and plenty of hard experience in order for its practitioner to make a living. Pressers produced the more complex, often ornamental pottery shapes such as square or oval-bodied wares that could not be produced on a wheel. Hollowware statuary was also largely press-moulded, the best known pieces being the cheap flatbacks, fairings and Staffordshire dogs that ornamented many a Victorian mantelpiece.

On 23 May 1838, the family suffered a loss when the head of the family, Edward Smith senior, died at the age of sixty-five. According to his death certificate he still lived in Well Street and the cause of his death was given as asthma, brought on perhaps by his years spent working in warm, dusty pot banks. He may have been ill for some time, as according to the death certificate he had prior to his death been reduced to working as a labourer. Two days later, his nephew George Redfern, who lived only a few doors away in Well Street, went to notify the registrar of his uncle’s demise. Edward Smith was buried at St John’s churchyard, Hanley, on 27 May 1838.

The death of Edward Smith senior could not have come at a worse time for his daughter Jane, who was planning to marry. Less than two months later, on 16 July 1838, Jane married potter Thomas Privet at Wolstanton parish church. Both bride and groom were at that time living in Tunstall. The witnesses to the marriage were her brother Edward Smith and a woman named Priscilla, whose surname is difficult to make out on the certificate. The reason for the marriage in haste only a matter of weeks after her father’s funeral seems to have been that Jane Smith was pregnant, her daughter Ellen being born just a couple of months later.

The 1841 census was the first survey of the British population to list individuals and households. This from a researcher’s point of view is a positive boon, compared to the simple head counts provided by the three previous censuses, but it was by no means perfect. The 1841 census listed street names, but not house numbers; individuals were named and their employment given, but their marital status, relationships to the head of the household and birthplace were not recorded, while the age of most people over the age of ten years was ‘rounded down’ to the nearest five years. Thus a man of thirty-seven would be ‘thirty-five’ in the census return, or a woman of fifty-three, would be ‘fifty’, though the rule was not always enforced rigorously. The enumerator who covered Well Street often stated a person’s true age, or rounded them down to the nearest decade.

On the night of Sunday, 6 June 1841, three people were listed as living at one particular house in Well Street, Hanley. The eldest of these was sixty-three-year-old Elizabeth Smith, whose profession was listed as ‘Ind’ – presumably shorthand for independent. The second individual was Edward Smith, whose age was given as thirty, though he was actually nearer thirty-five or thirty-six years old. Under profession, the census return has the words ‘J. Potter’, which probably stands for ‘Journeyman Potter’, in other words a skilled workman, but not yet a master potter; he was later described as such on his wife’s death certificate. The last person in the household was eighteen-year-old George Smith, who worked as a gilder, applying gold decoration to pottery.

The next household contained the large Simpson family and apparently three guests or lodgers, a widowed transferer, thirty-five-year-old Catherine Hancock, and her two children, ten-year-old Joseph and six-year-old Thirza. If the entry is correct then there were thirteen people living, or at least staying, in the house, a rather unlikely scenario given such a small building. Instead, Catherine and her children probably lived in the neighbouring house and the enumerator merely failed to indicate this. Still, there were connections between the Smiths, Simpsons and Hancocks. One of these is of considerable importance to our story, for by 1841, Edward Smith and Catherine Hancock were lovers and marriage was in the air.

Mother and Child

The mother of Captain Smith had been born Catherine Marsh, the daughter of potter Ralph Marsh, in Penkhull in about 180 . She appears to have received little or no education as a girl and on both of her subsequent marriage certificates Catherine signed with her mark. Indeed, the first time she appears in any documentation is on the occasion of her first marriage. This took place, after banns, at Wolstanton Church on 13 June 1831, when she married potter John Hancock. Although John and Catherine were married at the parish church, the available evidence, namely the baptisms of their children, indicates that they were in fact Methodists. They had probably not changed their religious beliefs in the interim, the simple fact was that Methodists had to get married in the parish church. In 1753, Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act had defined a legal marriage as one which took place in the Church of England, after banns and according to the rubric, old style common-law marriages being effectively outlawed. Only Quakers and Jews were exempt from this law, so between 1754 and 1837 all nonconformist marriages took place in Anglican churches. There seems to have been very little opposition to this, Methodists after all believed in many of the same religious tenets as Anglicans. Catherine seems to have been traditionally minded and even after 1837 she still preferred to get married in an Anglican church rather than one of the new-fangled registry offices.

Her first marriage was a short but fruitful one. John and Catherine’s first child, Joseph, was born on 26 June 1832; the second child, John, came along on 6 February 1834 and was baptised at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, Burslem, on 2 March 1834. John, though, only lived for eighteen months and his burial took place at Tunstall Christ Church on 30 August 1835. Then, on 1 January 1836, Catherine had a daughter, or possibly twin girls. Certainly local baptismal records show two girls named Thirra and Thirza, daughters of John and Catherine Hancock, as being born that day. On 7 January 1836, one Thirra, daughter of John and Catherine Hancock, was baptised at Wolstanton parish church. Thirza, however, was baptised at the Tunstall Primitive Methodist Chapel on 17 January. Thirra never appears after this, but Thirza certainly prospered, living to a grand old age and having children of her own. Thirra could have been her twin and perhaps died in infancy, though no burial entry has yet been found. The most likely explanation, though difficult to prove, is that they were the same person, namely Thirza Hancock. Perhaps she was a sickly child and her parents feared for her life, which would certainly explain the hurried Anglican baptism – any port in a storm – but she rallied and ten days later was rebaptised in her parent’s Methodist faith, her name being changed or corrected in the process.

There were no more children born to the couple, for in either 1838, or 1839, John Hancock died. The exact date of his death is not known for sure, as there were at least five separate John Hancocks who died locally at this time.

Up until this point, Catherine and her family had lived in the Penkhull-Wolstanton-Tunstall area, so what exactly prompted her move to Hanley in or around 1840? The Simpson family may have been the link. William and Hannah Simpson had eight children and the names of the three youngest were Joseph (seven years old), Catherine (five years) and Thirza (six months). It could be coincidence that these children had exactly the same Christian names as the Hancocks, or it could be an indication that the Simpsons were friends or relatives of Catherine’s, who had taken her and her children in, or put her into the neighbouring property that was up for rent in Well Street.

Certainly the Simpsons knew the Smiths, as Hannah Simpson was present a mere six days after this census was taken when, on 12 June 1841, Elizabeth Smith died at home. Two days after that, it was Mrs Simpson who went to the town hall to inform the local registrar of the death. The death certificate gives Elizabeth’s cause of death as ‘dropsey’(sic), otherwise known as edema, a condition caused by the abnormal accumulation of fluid in the body tissues or cavities, which causes painful swelling in the affected parts. Dropsy, it is now known, is a symptom of an underlying condition rather than a direct cause of death, the latter being most often caused by congestive heart failure brought on as a result of the condition.

Elizabeth Smith was buried at St John’s Church, Hanley, on 15 June. Many graves were exhumed in the twentieth century when the graveyard was reduced in size. Details of the memorial inscriptions of those graves that were removed were recorded, but there is no mention of Elizabeth Smith’s or her husband’s being amongst these, so they may still be there, though much of the site surrounding the sadly neglected church is today off-limits to the public.

The hasty burial was followed just under two months later by a happier event, namely the marriage of Edward Smith and Catherine Hancock. This took place at St Marks Church, Shelton, on 2 August 1841. According to the marriage notice carried in the North Staffordshire Mercury, Edward and Catherine were married at the ‘same time and place’ as another couple, Thomas Meigh and Isabella Lightfoot, both of Hanley.8 The surnames of the witnesses at Edward and Catherine’s marriage are difficult to make out, but they appear to read William and Julia Laynton. The information on the marriage certificate clears up one curious notion that has grown up concerning Captain Smith’s father. The dearth of information on Edward Smith prior to this event has led to speculation that he had contracted an earlier marriage and had children some time in his twenties, but on the certificate we read that Edward was a bachelor and there is no reason to believe otherwise. For a marriage to again occur so swiftly after a family tragedy seems rather unusual, but perhaps the match had been planned for some time. Whatever the case may have been, Catherine and her children Joseph and Thirza now set up home with her new husband.

For nine years afterwards we hear little of the Smiths or the Hancocks, a fairly sure sign that they settled down and lived their lives quietly. It was not until the end of the decade that they come into sight once again and when they do, it becomes clear with hindsight that subtle changes in their fortunes had taken place. These changes would eventually see the Smiths and Hancocks of this story leaving the Potteries for good and would propel the as yet unborn E.J. Smith to his long career at sea and eventually into the limelight.

The most notable differences were in the careers some of them had now begun to follow. Catherine Smith had given up working as a transferer on a pot bank and had begun working as a grocer, either on her own, or on some other premises, while her daughter Thirza found employment as a milliner and dressmaker. This may have been a family trade for the Hancocks, as in 1818 another Thirza Hancock is listed as a milliner and dressmaker in Hanley. The biggest break, though, and the most significant in the development of this story, came in late 1849 or early 1850, when Catherine’s eldest son, Joseph, left the Potteries entirely, travelled to Liverpool and entered the merchant navy. Why he did so is unknown, but it is clear from one account that Joseph, as either an example, or an active advocate, was later the chief cause of his half-brother choosing to go to sea himself.

That little half-brother, who would first emulate, but then surpass Joseph, now enters his own story. In 1849, Catherine Smith found that she was again pregnant and on 27 January 1850 she gave birth to a baby boy. He would be her last child and the only one born of the union of Edward and Catherine. They named their new son Edward John Smith, the first name doubtless after his father and the middle name came either from Catherine’s late husband, or in memory of the son she had lost fifteen years before.

The number of the actual house where the future captain of the Titanic was born has long been something of a bone of contention, as there is no house number given in the birth certificate, which merely states that he was born in Well Street. It has formerly been stated that Edward John Smith was born at 51 Well Street. The oft-quoted number 51 comes from the 1851 census where it appears alongside the street name beside the Smith family entry.9 However, the number here is not that of a particular house, but rather the schedule number, in other words the fifty-first building visited by one particular enumerator that day, not necessarily 51 Well Street. The matter of the house number was further confused over the following decades as the houses were renumbered on at least two occasions, probably as Well Street and the surrounding estate expanded. That this was indeed the case rather than the family simply moving house, is borne out by the fact that the Smiths and many of their neighbours occupied the same houses relative to one another over this period. Thus, by 1861, the Smiths’ home had become number 17 Well Street and by 1871, the last occasion that Edward John Smith was included on a census in his native town, his old family home had become 30 Well Street. The clue to the real number of the house where he was born can be found in the 1851 edition of Slater’s Classified Directory for Birmingham, Worcester and the Potteries. Though Edward’s address had no number, two grocers on either side were numbered. Totting up the numbers in between, it seems that in 1850 the Smiths actually lived at number 86 Well Street. As further confirmation, when Edward’s brother George Smith got married a couple of years later he gave his address as 86 Well Street where he was still living with his brother and his new family.10

At the time of Edward John Smith’s birth, the property comprised a ‘house, shop and yard’. This was probably just an ordinary house, the front parlour of which was converted into a store – a fairly common practice even in the late twentieth century. Certainly the Smiths’ store easily converted back into a family home when Catherine Smith left the area in the late 1870s. In the 1851 edition of White’s Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire, Edward Smith of Well Street is listed as a ‘Shopkeeper’, though, as noted elsewhere, it was probably Catherine who actually kept the shop. Though both Edward and Catherine were at times described as grocers, they are not here listed under that heading. The same distinction was made in the 1852–53 edition of Slater’s Classified Directory. The Smiths appear to have run something akin to a general store selling (according to White’s Directory) flour, cheese and other household goods as well as groceries.

Schooldays

Though no baptism record has yet been found, young Ted Smith, as he was known in his youth, was probably a Methodist. He certainly attended the Methodist British School in the nearby village of Etruria. This seems to have occupied the old Sunday school building at the rear of the New Connection Wesleyan Chapel which still stands in Lord Street, Etruria, not far from the Wedgwood pottery factory around which the village was originally built. The school later reverted to being a Sunday school, while the regular day pupils were absorbed into the Etruria Board School that opened in 1881 and was finally demolished in 2005. The old British School building itself is long gone and no pictures of it seem to exist. The closest we get is in a photograph of Etruria taken in 1865, in which the side walls of the chapel can be discerned, the Etruria British School, though, is out of the picture. As if to echo this lack of an image, surprisingly little textual information survives about the school, the Victoria History for Staffordshire barely notes it and E.J.D. Warrillow’s History of Etruria tells us only a little more. There is scant information about its origins, though it became very closely tied to the Etruria Unsectarian School. This had been an infants school founded in 1847 by Francis Wedgwood, the grandson of the famous Josiah Wedgwood, which later effectively became the British School’s infants department. This suggests that Francis also endowed the British School, but as a junior school to take the children who had attended the Unsectarian School.

The British School was founded in 1851; the earliest reference to it in the local directories was in 1852–53, but it appears to have had a good reputation from the start and embraced the Methodist doctrines that the Smiths obviously wanted their child to inherit. Like all schools of its ilk, the Etruria British School was a private institution. Parents had to pay for their children’s education as free compulsory state education did not start until 1890. As there are no figures for the school Smith attended, we can only make comparisons. For instance in 1843, children at the nearby Shelton British School paid 2d a week, while in 1862, the Etruria Unsectarian School that took over from the Etruria British School, charged 3s a month. The sums demanded seem paltry today, but even these small amounts were often more than the average family could afford in such a poor area. In 1843, the Shelton School had 180 boys and 108 girls on its books, but as the teachers admitted only 100 of the former and eighty of the latter attended regularly. The rest were absent in the main because their parents could not afford the fees every week, or even a decent set of clothes to send them in. It was also revealed that many boys were taken out of school early to start work, while girls were required to look after the home while their mothers went out to work. Joseph Lundy, the master at the Shelton School, felt that this was a great pity, as those pupils who stayed on for any length of time did well in their studies.

The Etruria British School was a monitorial school, so called because the responsibility for a great deal of the teaching was delegated down a chain of pupil monitors from one class teacher. The schools of this type were usually subdivided by religious faith; the Anglican community was largely catered for by the National Schools, while the Nonconformists sent their children to the British Schools. These employed the Bell or Lancaster systems of tuition respectively. Both were systems (arrived at separately) whereby a very limited number of teachers could hand the lessons over to the monitors, who would see that the large classes each got the same amount of tuition per pupil. Both systems demanded heavy regimentation of the schoolchildren, and inevitably analogies have been drawn with the factory system then in operation. Despite the overtones, though, this was not a middle-class ploy designed to produce workers ready for the factories, it was simply the best method for the situation; only in this way, as Joseph Lancaster noted, could 500 children be taught from one book instead of 500. In fact, at its simplest the monitorial system was a variation on the theme of learning by rote that had been employed for centuries. Such a method of learning could have remarkable results – Shakespeare, for instance, learnt his lessons by rote. But, as critics of the monitorial system noted on more than one occasion, less able pupils were left behind as the lessons steamrollered on and the benefits to all were lost if the teaching was poor, while real problems would result if the monitors under the teacher’s tutelage did not fully understand what he or she had been taught.

The schools’ governing bodies supplied each local branch and school with a simple set of ‘readers’. These were printed sheets bearing excerpts from books that could be held up in front of a class for the pupils to copy. At first in both National and British Schools, these readers were drawn almost exclusively from the Scriptures, but by the 1850s, both societies had come to realise that the Bible, though a useful and familiar text for children to begin with, had its limitations in the increasingly complex society that was nineteenth-century Britain, where secular knowledge counted for much more than familiarity with the Scriptures. As a direct result of this realisation, a set of secular readers had been introduced in the mid-1840s. Instead of the old religious tracts written by divines, these were written by people who espoused the ‘new religion’ of political economy that had come with the rise of industry. These new readers extolled the habits that children were expected to cultivate in this new order such as diligence, forethought, frugality and temperance and explained the perils of neglecting them, allied to dire warnings of the dangers to the working man of rocking the economic boat. The laws of political economy were also invoked to argue against trade unionism and the futility of government intervention in wage disputes. Basically, it embodied all of the principles that the middle class wanted the working class to believe in.

Not that the children were aware of this, and the pill was sweetened by presenting it in many varied and often very familiar forms. For the youngest, there were fairy stories and fables, the traditional moral endings of which were given a new slant to fit the new belief system. As the children grew older, the new secular readers provided a much wider range of textual material that would give them a much better grasp of the wider world. One suggested curriculum for schools using the new readers was drawn up by a training college inspector in 1848, ‘…biography (of good men); natural history; the preservation of health; cottage economy; horticulture; mechanism; agriculture; geography; history; grammar; natural and experimental philosophy; money matters; political economy; popular astronomy.’ 11

In most monitorial schools, the school day was regulated with almost military efficiency. Discipline was strict and disruptive pupils were punished quickly. There were, however, no beatings in a British School. Being a Quaker, Joseph Lancaster had opposed the use of the cane under his system and he instead advocated punishments that would shame, exhaust or terrify the malefactors. These could range from something as simple as having the pupil wear a dunce’s cap, to thoroughly Byzantine punishments, like fastening a heavy log around the children’s necks and making them walk around the school until they dropped, tying them up in sacks, or hoisting them up to the ceiling in a basket until the end of the lesson.

Though ousted from its paramount position in the curriculum, piety was still rigorously enforced, as too was deference to their elders, children being drilled to ‘know their place’ and ‘respect their betters’. In National Schools, the attitude towards such indoctrination was that it taught the children to put up with their lot in life now, and to happily accept the existing status quo when they became adults; the attitude in British Schools, though, was different and to twenty-first-century eyes surprisingly modern. Though the emphasis was still there to respect God and their elders, the education they received was instead extolled as a benefit by which they could better their lot in life. This was a subtle difference, but a telling one nevertheless, and indeed in later times many of the old boys of the Etruria British School did exceptionally well in their chosen careers, Ted Smith being one of them.

The Patriotic Schoolmaster

Good teachers helped to push the message home and the Etruria British School seems to have been able to attract better than most. The trade directories of the time tell us the names of the head teachers at the school. The first of these, mentioned in the 1852–53 edition of Slater’s Classified Directory, was Jane Vickers. In a separate entry in the same book, one John Vickers is noted as being a schoolmaster at Etruria, though at which school it does not say. The Vickers’ tenure, though, would be brief and the school soon had a new head teacher who would have a profound effect on the pupils he taught.

We all remember our favourite teachers, the people who influenced us and helped to shape us for adult life, and the boys of the Etruria British School were no different. By the mid-1850s, the school had as its headmaster Alfred Smith, a native of Derbyshire, who was a much loved and respected teacher by the standards of the time. Spencer Till, a school friend of Ted Smith’s, later recalled their ‘much respected master’, while another old school fellow, Joseph (Joe) Turner, called him ‘dear old Alfred Smith’. Only a few years after Ted left his school, Alfred Smith was appointed as the first secretary to the Hanley School Board, whilst he also spent time giving private tuition to future local luminaries such as Cecil Wedgwood, a scion of the famous potting family who in 1910 became the first mayor of the newly federated Stoke-on-Trent. A measure of the esteem in which he was held can be gained by seeing how in later life many of the old boys, including Ted Smith, would attend a reunion in their old teacher’s honour.

Alfred Smith died at the age of seventy-eight in 1911, but in the 1850s he was still a vital young man in his twenties and, it seems, a fiery patriot. According to Joe Turner, the boys under his charge were taught to love ‘God, Queen and Country’ and he often regaled them with tales of brave British deeds. This would make a deep impression on many a lad. Joe Turner, who would himself later go to sea, wrote, ‘I have often thought that there are few schools in our country that produced the number of soldiers and sailors that the Etruria British School did, and this was in a great measure owing to the patriotic fervour of our schoolmaster.’12

Ted Smith for one certainly took Alfred Smith’s teachings to heart and he was instilled with a deep love of his country and its achievements that never left him. In the aftermath of the Titanic disaster, though his name was essentially wrapped in the flag by the popular press, those who knew him personally vouched for the fact that Smith was indeed very proud to be British. The publisher J.E. Hodder Williams wrote:

He was very British, almost insular for a man who had travelled so widely. His last command as the waters rose to the bridge, ‘Be British,’ was what we expected and wanted him to say. He belonged to the race of the old British sea dogs. He believed with all his heart and soul in the British Empire. He had added that to his creed.13

We even know of one of the tales that may have fired Smith’s patriotism and inspired him in his hour of need, for Joe Turner recalled with some irony in later life how he had listened with fascination to Alfred Smith’s rendering of the wreck of the Birkenhead.

The HMS Birkenhead had been a troopship ferrying soldiers drawn from several regiments, plus their wives and children, to Algoa Bay, Cape Colony to take part in the 8th Kaffir War. Its journey from Britain had passed without incident, but early on the morning of 26 February 1852, as it neared its final destination, haste and a strong prevailing current resulted in the ship being driven too close to the coast where it impaled itself on a rock off Danger Point on the outskirts of Cape Town. As the ship began to break apart the crew discovered that there were not enough serviceable lifeboats for all on board and so at the request of their officers the soldiers famously formed ranks and stood firm as the ship broke up and went under, thereby allowing the women and children to escape in the remaining boats. Of the 643 people on board only 193 survived the disaster and the soldiers’ chivalry gave rise to the ‘women and children first’ protocol that male passengers and crew were expected to abide by should they be unlucky enough to be caught in a shipwreck.

This astonishing story of self-sacrifice fascinated the Victorian world in many of the same ways that the story of the Titanic would the people of the twentieth century, and the conduct of all future evacuations, including the Titanic, would be measured against this yardstick. Doubtless Ted Smith heard this tale, if not from his teacher then certainly at some point during his long career at sea, and it seems more than likely that the hard lessons taught by the men of the Birkenhead had a bearing on how he tried to manage his own evacuation half a century hence.

A Day at School

If he had started school as an infant, doubtless Ted’s mother or father, or perhaps even Thirza, would have taken him to school at first, but as he got older and made friends, Ted began to go to school in the company of other boys. One of these, William Jones, later recalled how half a dozen of them used to travel into school every morning. ‘I remember how Vincent Simpson used to call on me first and how we would call for Johnny Leonard. Then the three of us would knock at Ted Smith’s door and having collected the others we would run down Mill-street and Etruria-road to school.’14

The route they took still exists, though it has changed a great deal in the interim. Jones’ ‘Mill-street and Etruria-road’ are now Etruria Road and Lord Street respectively. They form part of a busy thoroughfare linking the Potteries and Newcastle-under-Lyme and serve a number of brash out-of-town superstores and multiplexes. In the middle of the nineteenth century, though, Mill Street was bordered by corn fields and Etruria Road was guarded by a toll gate and passed through a thick copse of mature trees, known simply as the Etruria Grove. Prime dawdling country for your typical schoolboy if ever there was any.

School would start at 9a.m. for all classes. At the Shelton British School there were classes for boys, girls and infants in separate classrooms. The Etruria School was apparently the same, though only boys are ever mentioned in the accounts that have survived. Before the lessons began, the school said the morning prayer, then the senior monitor called out all the lesser monitors and asked for a head count of each class. Considering that Ted Smith was to spend the majority of his adult working life in a job where a hierarchical chain of command governed his existence, such roll calls would remain very familiar.

After the head count, on command the children sat down on bare wooden benches and waited for their orders. The head monitors received the lesson from the teacher or headmaster, then gave out the letters or phrases to be copied and these were written either on a blackboard, or on a card, which was held up before the whole class, who then copied it out on their own small slates. When they were all done, the senior monitor called out, ‘Hands down. Show slates,’ and the monitors then did the round checking for any mistakes before further orders of ‘Lay down slates,’ ‘Clean slates,’ and ‘Show slates clean,’ were issued. Then a fresh set of words and phrases were set out and it started all over again.

Age largely dictated what they were taught. The younger pupils usually had their mornings given over to writing or reading and spelling lessons, where groups of children would be brought out to read from the board. Alternatively a monitor would come in with a card bearing the alphabet and the class would say each letter out loud as it was called out. The children were also tested on their ability to count to 100 accurately. As the pupils grew older, though, the lessons would have become much more involved and taxing. The new readers encouraged pupils to analyse and dissect the passages or subjects they were studying and they often came with a list of questions or critical notations. The teacher would take the pupils through the passage and question them as to what it meant, or at least be asked to give their own interpretation of its meaning.

At about 10.30, there was a five-minute break before they returned to their lessons. These carried on until about 11a.m., when the class had to study their catechism or religious induction, so important to the Victorian sense of religion: the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments and a few psalms, all taught in the same manner as the alphabet. After that was done, the class said grace ‘before meat’ and at noon went home.

Lessons resumed at about 2p.m. The children said grace ‘after meat’ and then got back to their routine. For the youngest pupils, the afternoon was spent in the same manner as the morning, but as the scholars got older the afternoons were given over increasingly to arithmetic, tables and accounts. At 4.30, more prayers were said, followed perhaps by evening hymns. Then, finally, the children were allowed to go home.

Of course, it is only possible to speculate how close all this was to the routine Ted knew at school, as the system did vary, but that the school did operate along these lines is perhaps borne out by the fact that Ted numbered among his closest friends boys that quite often were many years his junior, so if he had taken up the duties of a class monitor, he would have had occasion to meet many of them from day to day. For instance, there was Edmund Jones who knew him as a senior boy at the school and considered him to be ‘a quiet, respectable, courageous lad who never put himself to the front too much’. Jones also recalled that Ted was always on hand to defend the weaker and younger boys if anyone ever fell to bullying them.15 Spencer Till, the son of an Etruscan grocer who was to remain lifelong friends with Ted, was seven or eight years his junior.

Joe Turner was two years younger than Ted. He, though, remembered him in a rather different light, as ‘a high-spirited lad’ as Alfred Smith was want to call such boys, and at first the two of them were at odds with one another:

Ted Smith quarrelled with me many times and used to punch my head, and I returned the obligation. These quarrels became so incessant that our dear old schoolmaster cautioned us before our class that they must be stopped, but if we wanted to cudgel ourselves, we must go out in Hall Fields and cudgel each other to our hearts’ content. I am sorry to say that we both took such advice and met after close of school. My second was Herbert Greatbach. Ted Smith’s was my brother Edward. After the fight had progressed for some time with sword sticks, I inadvertently struck Ted Smith on the neck, and this so infuriated Smith that he rushed on me, put down my guard, and thrashed me until I howled.16

Like most schoolboy quarrels, though, one good fight seems to have cleared the air and in time Ted and Joe grew to be the best of friends.

Out of school, Ted spent a good amount of his spare time out playing with his mates. The gang of lads who ran down to school with him every morning seem to have numbered amongst his close friends. William Jones recalled that he and the others spent many happy hours together before and after school. The reporter who interviewed Mr Jones after the Titanic disaster, was shown an old faded photograph of the six boys, ‘in which the bright, determined face of the boy who was to be the leading figure in the world’s greatest maritime disaster stands out conspicuously.’ 17

These though were not the public school boys of Tom Brown’s Schooldays,