6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

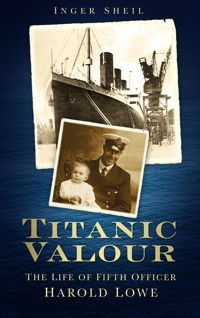

Harold Lowe, Fifth Officer of RMS Titanic, was described by another survivor as 'the real hero of the Titanic.' After taking an active role in the evacuation, Lowe took command of a raft of lifeboats, distributing passengers among them so he could return to the wreckage and look for survivors – the only officer to do so. He succeeded in raising a sail, rescued the drenched inhabitants of a sinking lifeboat and towed another boat to safety. Lowe had a long and fascinating life at sea. The tragic sinking of the Titanic was only the most notorious incident in a career that took him as a fifteen-year-old runaway to the coast of West Africa and into action in Siberia during the Russian Revolution. Titanic historian Inger Sheil has worked closely with Lowe's family to compile a gripping biography of this heroic Welshman.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Senator Bourne: Did Officer Lowe call for volunteers to return to the wreck?

Mr. Crow: No, sir; he impressed upon us that we must go back to the wreck.

From evidence given by Titanic crewman George Crowe at the 1912 Congressional Subcommittee investigation into the Titanic disaster

I have never prided myself upon being a prophet, but of this I am positive: When the Titanic disaster has become a matter of history, Harold G. Lowe will occupy the hero’s place. The reason is that in you were combined the qualities of Courage, Firmness and Good Judgement.

None of your brother officers lacked courage, but your exceptional demonstration of the latter qualities will mark you as the one who secured the results. In this country at least we honour most the man who gets results.

Sheriff Joseph E Bayliss, Sergeant at Arms to the United States Senate, 20 May 1912

For my parents Sandra and Ted Sheil

Who taught me to love the sea, but to never turn my back on it

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Reading works on the most famous shipwreck of all, the loss of the RMS Titanic, one name kept appearing. It seemed that whenever something interesting was being said or done during this unfolding disaster and its aftermath, Harold Lowe was involved. I looked in vain for a complete biography of this colourful individual – none existed. The fragments in secondary sources about his life before and after the sinking were sketchy at best. So I embarked on a journey to find out the truth about this intriguing man, and found not only supporters along the way, but friends.

This book would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of Harold G. Lowe’s descendants. Harold’s son, Harold William George Lowe, was receptive to the idea and in turn introduced me to his children, Godfrey and Gerri, and his nephew John Lowe. It is said that families can be the enemy of biographers, but in the Lowe family I found allies of the very best kind. Harold W.G. Lowe wrote to me in an early letter that ‘all I would seek is accuracy. I would not want [my father] to receive any more praise or blame than is his due.’ It is a spirit of which his father would have approved, and which all the family has demonstrated. While doing their utmost to help with information and suggestions, no member of the family has ever sought to dictate the narrative or direction of this book. Sadly, Harold W.G. Lowe passed away before seeing the work completed – I hope it would have fulfilled his hopes for it.

In North Wales I met Captain John Lowe and his wife Cara, who have more than once extended their warm hospitality and have gone far beyond any call of duty to make their family archive accessible and facilitate the necessary research. John, with his background in the mercantile marine, has provided invaluable insight into his profession. Godfrey Lowe and his wife Bernie generously shared information as we explored Barmouth and travelled to Llandudno and Deganwy together and have been continuously supportive. I value all these friendships very much. Other members of the family, including Harold W.G. Lowe’s wife Peggy Lowe, Janet Lowe and Harold G. Lowe’s nephew John Lowe (son of Arthur Lowe) have also contributed immeasurably, as did Barbara Whitehouse who shared her childhood memories of the Lowe family in Deganwy.

My good friend Kerri Sundberg was a major inspiration for this project and this book owes much to her talent and passion for the subject. Titanic author David Bryceson has been an ongoing source of support, and kindly gave me his extensive correspondence with Harold W.G. Lowe about his father.

Author and researcher Senan Molony has been a fount of practical support, providing extensive input into this book’s final form, for which I am very grateful as much as I am for his constant urgings to publish. John Creamer has been exceptionally generous with use of images and permission to quote from documents in his collection.

It is a matter of great regret for me that this book was not completed before Ted Dowding (nephew of Titanic survivor Clear Cameron) and his wife Dinah passed away. They were dear friends, and kindly gave me permission to quote from their book Clear to America by Titanic and Beyond, a collection of letters by his aunt and her friend, Nellie Walcroft.

The following individuals – researchers, authors and the relatives of those who sailed – made this work possible: Jenni Atkinson, Mark Baber, Stephen Cameron, Miriam Cannell MBE, Mark Chirnside, Alex Churchill, Andrew Clarkson, Pat Cook, Mary Conlon, Kate Dornan, Ted and Dinah Dowding, David Fletcher-Rogers, Christine Geyer, Phil Gowan, David Haisman, Steve Hall, Olga Hill, Phil Hind, Ben Holme, Tom Hughes, Daniel Klistorner, Roseanne Macintyre, Ilya McVey, Fiona Nitschke, Andrew Rogers, Bill Sauder, Eric Sauder, Monika Simon, Parks Stephenson, Brian Ticehurst, Mike Tennaro, Geoff Whitfield, Mary-Louise Williams and Pat Winship.

I am also deeply indebted to the staff of the following institutions and organisations: my colleagues at the Australian National Maritime Museum, the Bayliss Public Library, the British Titanic Society, the Colindale Newspaper Archives, the Gwynedd Archives, the Encyclopaedia Titanica messageboard, The National Maritime Museum (UK), the Liverpool Archives, the National Archives (UK), The Memorial University of Newfoundland Maritime History Archive, the Royal Naval Museum, The Provincial Grand Lodge of North Wales, Southampton Archives, The Titanic Historical Society, the Titanic-Titanic messageboard and the staff of The History Press.

Finally, my own ‘flotilla’: Rebecca, Cameron, Lachlan, Gabrielle and Kieran Bryant; Edward Sheil; Alison Fahy; Jill, Glyn and Nicholas Raines; and my parents Ted and Sandra, to whom this book is dedicated.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Chapter 1

‘Where Are You Bound?’

Chapter 2

Boatman and Sailor

Chapter 3

In Line of Reserve

Chapter 4

‘A Good Bridge Officer’

Chapter 5

White Star Line

Chapter 6

A Stranger to Everyone on Board

Chapter 7

Mayhem on the Titanic

Chapter 8

Launching Lifeboat 14

Chapter 9

‘I’ve Taken Command Here’

Chapter 10

The US Titanic Inquiry

Chapter 11

A British Reckoning

Chapter 12

In Peace and War

Chapter 13

The Bolshevik Business

Chapter 14

Families in Decline

Chapter 15

‘Before I’m Too Old’

Epilogue

Appendix I

Affidavit of Harold Lowe

Appendix II

Career History of Harold Lowe

Plates

Copyright

PROLOGUE

When RMS Titanic took her 2½-mile plunge to the ocean floor, she left behind her on the surface a slight haze, strewn bits of wreckage, and many hundreds of screaming men, women and children.

The last lifeboat successfully launched had left the ship shortly after 2 a.m., pulling away into the dark. Still aboard the Titanic were some 1,500 people. These were soon plunged into the 29°F water, where they began freezing to death. Their cries would haunt the 712 survivors in the encircling lifeboats for the rest of their lives. They were ‘terrible cries’, ‘awful cries, and yelling and shouting.’

A few of those in the water crawled aboard two canvas-sided lifeboats, so-called ‘collapsibles’, which had floated free from the boat deck as the ship sank. Balancing on the keel of Collapsible ‘B’, which had overturned during attempts at launch, or up to their knees in the freezing water of swamped boat ‘A’, they were only marginally better off than those in the water.

For most, rescue would not be forthcoming. Entire families perished that night in the pitiless North Atlantic. The Goodwins (father, mother and six children), who had hoped to settle in Niagara Falls, were swept away by the cataract. All eleven members of the Sage family, travelling third class like the Goodwins, were obliterated. The Rice family from Ireland, the Anderssons from Sweden – all died.

The lifeboats waiting out in the darkness were almost all under-filled. With their total capacity for 1,178 people, at least 466 places went unoccupied. The few in the boats listened in fear and anguish. They did not go back.

In Boat 1 fireman Charles Hendrickson broached the question of returning. The idea met with a lukewarm reception, and no attempt was made. In Boat 6 the ladies implored Quartermaster Robert Hichens to return. He announced: ‘It’s our lives now, not theirs.’

Fourth Officer Boxhall lit a flare in Boat 2 and the volume of shrieks briefly swelled up louder than before. Third Officer Pitman, in command of Boat 5, declared, ‘Now, men, we will pull toward the wreck’, but ‘very nearly all’ the passengers objected, fearing for their lives. Pitman then ordered his men to lay by their oars, and Boat 5 continued to drift, its occupants listening to the ‘crying, shouting, moaning’.

Able Seaman Fred Clench told the people in his boat the voices came from men in the other lifeboats, shouting to each other so they did not get lost in the darkness. For one survivor, the howls seemed to ‘go on forever’. Pitman estimated ‘a continual moan for about an hour’. Then the voices died away from the dark Atlantic’s surface, and one by one fell to silence.

Some distance away from the mass of people, a young ship’s officer had been rounding up as many lifeboats as he could find in the gloom of the moonless night. Tying together lifeboats 14, 4, 12 and Collapsible ‘D’, he told them: ‘All right, consider the whole of you under my orders; remain with me.’

While the people in other boats rowed, sang to drown out the cries, or simply sat deaf to the final nightmare, the officer had been busy transferring passengers out of Boat 14 to prepare a return to pick up survivors. He waited until the moment he could safely return without endangering his handful of crew.

Now, he judged, the moment had come. Harold Godfrey Lowe, fifth officer of RMS Titanic, turned to those under his charge and told them they were going back.

CHAPTER 1

‘WHERE ARE YOU BOUND?’

Composed and apparently fearless in the face of loud and threatening voices, Hannah Lowe rode into the crowd that surrounded John Wesley. The mob had every intention of stoning the preacher for the crime of delivering a sermon out of doors. This practice faced bitter opposition in these early days of Methodism, and encounters between the evangelicals and their opponents often led to more than a clash of words. Hannah, distant great-aunt of a Titanic officer, was no stranger to this threat of mob violence; her father, George Lowe, was one of Wesley’s staunchest supporters and had helped him establish chapels in Chester. Now Hannah stood as the only obstacle between the angry local men and the target of their wrath. An accomplished equestrienne, she placed her horse and herself between Wesley and the riotous throng and surveyed them coolly.

‘The first stone at the preacher will come through me,’ she announced.

The crowd, nonplussed at first, distracted, lost its purpose. It gradually dispersed under Hannah’s watchful eye, leaving Wesley unharmed. Or so ran the legend.

Nestled in the shadow of the Welsh mountain Cader Idris, by the mouth of the river Mawddach, Barmouth remains today much as it was in previous centuries. The picturesque community is one of the towns and hamlets girdling a stretch of the coast in the thin border between the hills and the sea. Said to be the seat of Idris the Giant, legend has it that anyone sleeping overnight on the mountain will awake either a madman or a poet. The town’s buildings extend in tiers up the lower slopes, the natural barrier to the inland emphasising the sea alone as the sustainer of Barmouth’s people, from the once-thriving shipwrights and fishermen, to the bed-and-breakfast trade today.

Barmouth had been home to a busy shipbuilding industry. In the mid-eighteenth century it was counted asone of the major ports of Wales, but by the 1840s two major factors converged to ensure its decline. The development of Porthmadoc to the north as a shipping centre, and the emergence of the railway in coastal transport and trade combined to radically alter the town’s economic base.

The railway worked both ways. Although the town’s history as a sea bathing resort dated to 1766, for the first time holidaymakers from industrial centres inland could avail themselves of easy access to the coast. The Barmouth of the second half of the nineteenth century adapted to a seasonal influx of holidaymakers.

The small resort town’s natural beauty, where even the buildings seem hewn out of the grey stone of the hills, may be what drew George Lowe. His artist’s eye must have seen the bare-canvass potential of ocean, estuary and clouded mountain peaks. He would paint these scenes many times in the years to come. George Lowe, from the line of fearless Hannah Lowe, selected a site on the southern approach to the town, a patch of land halfway up the hill with views far inland along the Mawddach estuary. The land dropped away sharply where he would build a house for his family, straight down to the estuary, with ready access to the river and tidal flats that fringed the Irish Sea. With walls several feet thick in places to withstand the Welsh winters, the house was substantial inside, being some three storeys over a basement. It was named Penrallt, Welsh for ‘House on the Slope’.

Harold Lowe was born, raised and died in Wales. His family origins, however, were neither Welsh nor Celtic, although his ancestors came from just over the Marches in Cheshire, England. The legend was that they could trace their ancestry to one of William the Conqueror’s men, Hugh D’Avranches, better known to history as Hugh Lupus, Hugh the Wolf.

He had been made Earl of Chester in 1069 for his part in suppressing the rebellious Welsh. To the Welsh he was Hugh Vras – ‘Hugh the fat’ – whose gluttony made him so obese that he could hardly walk. Yet it was also said that, fat or no, he also fathered a number of illegitimate children.

Harold Lowe’s faith in the family’s connection with the waddling, swaddling Earl of Chester would be demonstrated through his use of a heraldic device – the snarling wolf – that signified Hugh Lupus. But the first firm foundations for his line can be traced to 1589 when the Lowes were simple farmers at Guilden Sutton, Cheshire. Their connection with farming continued until the latter part of the eighteenth century, when George Lowe (1738–1814), father of Hannah Lowe, became a successful miller and flour dealer. A Freeman of Chester, his sons George and Edward became a silversmith and clockmaker respectively. The thread of these occupations passed down through generations, and for over a century the Lowes found their calling as skilled artisans.

George Edward Lowe was born in Chester on 20 April 1848. It was the year of revolutionary upheaval in Europe; appropriate for the boy who would grow up to be somewhat unconventional. It had seemed that he would follow in the footsteps of his father, his earliest described profession being that of goldsmith or jeweller and watchmaker. There is some suggestion that the family cultivated artistic connections; the 1881 census listed a young artist, Walter Deken, as a visitor to the Lowe household. George Lowe was of a somewhat flamboyant, even bohemian character, and rather than continue the family tradition of metalwork and clockmaking, he was drawn to painting, and oils in particular. Yet for many years he would continue to list his occupation as ‘jeweller and watchmaker’, being a member of the family firm of Lowe & Sons, with shops in Chester, Llandudno and Liverpool.

George met Emma Harriet Quick when he was working in the Liverpool shop. Harriet, as she preferred to be known, was a local girl, born in Liverpool on 24 March 1856, the youngest of Anne Theresa and Thomas Lethbridge Quick’s four children. Thomas Quick was a district police superintendent, a comparatively new occupation. The ‘New Police’ had only been formed in 1836 as a result of Robert Peel’s Municipal Corporations Act (1835), which also gave rise to the popular colloquialism ‘peelers’. Thomas, originally from Merton in Devonshire, had served with the Metropolitan force before being reassigned to the Liverpool dock force. He saw lively service in the early days of the Liverpool police, when rows and riots were almost a daily occurrence on the docks. The dock force was later amalgamated into the town force, and he was appointed a borough superintendent. He was a man of considerable personal courage, in keeping with his occupation, and it is recorded that he once imperilled his life to save men trapped in a burning building. His wife Anne, whose parents were of some means, was a Liverpool girl. A brief, elusive description of her ‘loving heart and constant tenderness’ is virtually all that survives of her reputation; she predeceased her husband.1

Hannah grew up with her siblings Thomas, Elizabeth and Robert at the police station in Olive Street where they lived with the Bridewell keeper, his family and several servants. The children could not help but be aware of the cast of characters that came and went in the station: the innocent, the unfortunate, and the denizens of Liverpool’s underworld. There was early tragedy in Hannah’s life; her mother had already passed away when her father, who had suffered from heart disease for years, suffered a stroke in mid-1867 resulting in partial paralysis. On 4 December 1867 he suffered another stroke and passed away at their home in Everton, where the family had moved following his retirement. There was more sorrow to come when Thomas’ oldest child and namesake, banker’s clerk Thomas Lethbridge Quick Junior – fifteen years older than Harriet – began exhibiting what were diagnosed as the symptoms of insanity. The younger Thomas died of phthisis on 7 August 1872, barely a month after his admission to the Ashton Street Lunatic Asylum.

Hannah remains a rather elusive figure, beyond such shadowy details as her preference for her middle name. How she met and became enamoured of George Lowe remains obscure, but on 6 June 1877, when she had just passed her twenty-first birthday, Harriet married her charming beau. Initially they set up house in Llandudno, North Wales, with a single maidservant. Their son George Ernest Lowe, first of what was to be a large family, was born in 1878. A daughter, Ada Florence, followed in 1879. In 1882 George and Harriet – now pregnant with their third child – moved into George’s father’s home, ‘Bryn Lupus’, in Eglwysrhos, a stepping-stone to Barmouth.

It was in his grandfather’s home that Harold Godfrey Lowe was born on 21 November 1882. The date and place of birth are established beyond doubt, but for a time in his life the future Titanic officer was either uncertain or dissembling these details. As late as 1910 some documents would record his year of birth as 1883, and the place as Liverpool.

Although they left Bryn Lupus while he was still a baby, the name of his grandfather’s home struck a family chord. The name ‘Bryn Lupus’ translates as ‘Wolf Hill’. Many years later, after his own retirement, Harold Lowe had stained-glass panels set into the door of his home with the slavering wolves of Hugh D’Avranches.

The young family moved more than once in these early years of Harold’s life. By 1884, George, now describing himself as simply an ‘artist’, had set up residence with Harriet and brood at Bronwen Terrace, Harlech. Between Portmadoc in the north and Barmouth to the south, Harlech had prospered around a castle, built by England’s Edward I as part of a ring of fortresses intended to subdue the rebellious Welsh.

The Lowe family continued to expand with rapidity. Another daughter, Annie May, was followed by Edgar Reginald, born on 20 September 1884. Harold and Edgar’s proximity in age – just two years – was reflected in their closeness as they grew up. Both were fated to go to sea.

First there was Barmouth. By 1893 George Lowe took his family on their final move, to Penrallt, the House on the Slope, scene of an idyllic childhood on the edge of Tremadoc Bay.

Tremadoc had a fierce reputation. In March 1893 the SS Glendarroch, out of London for Liverpool, ran aground on St Patrick’s Causeway. The Barmouth lifeboat successfully rescued all the crew, as it would again just five weeks later when the ketch Canterbury Bell was wrecked in identical circumstances.

In 1895 the causeway almost claimed the four-masted barge Andrada that was beached for several days. In August that year the Barmouth and Pwllheli lifeboats laid out anchors from the stranded barque Kragero when she ran aground in rough seas and a southwesterly gale.

The boy Harold Lowe, like other residents of Barmouth, would have been well aware of these dramatic incidents and rescues. He was learning the perils of seafaring, while also becoming fired and inspired by the actions of ordinary men in lifeboats facing grave personal danger to save the lives of others.

Although the heyday of Barmouth as a centre for shipping was over, coastal ships and tramps still arrived with regularity. Nautical themes entered George Lowe’s work, and subjects such as the coaster SS Dora featured in his paintings. For the Lowe boys, the sea was both an educator and an entertainer. In time, it would become a livelihood. In years to come it would also take a cruel toll on the Lowe family and it never ceased to be an integral part of their lives.

Lessons in the crafts of the sea began early, with long hours spent along the river, the estuary and out to sea, fishing. The oldest boy, George Junior, used his punt to carry people across the river Mawddach. His younger brothers tagged along and would come to know his circle of friends, the other boatmen who worked the same trade.

Visitors who took to the boats or indulged in sea bathing were not always water wise, and the estuary and seafront were hazardous. Tuesday 7 August 1894 saw Barmouth in the full swing of the summer season. Visitors poured into the resort, took walks up in the hills to the Panorama lookout, and hired boats on the Mawddach. Pleasure-seekers and townsfolk alike were shocked out of the holiday mood when the estuary, living up to its dangerous reputation, claimed several lives in the worst accident in the collective memory. A party of visitors, members of the National Home Reading Unit, hired three local boats to take them up the estuary to Bontddu, and then planned to return with the outgoing tide.

One boatman refused to hire his boats to the party as he felt the tides were too dangerous. Another, William Jones, required considerable persuasion before agreeing to take out his boat out. One of the other vessels was in the charge of a local boatman, Lewis Edwards, while a third group was led by Oxford University student Percival Gray, who felt himself accustomed enough to rowing. Several of Gray’s friends intended to accompany the group, but felt that the river was too rough and the wind too strong. More than one boatman on the quay advised them not to go.

The party arrived safely upriver in spite of a strong out-flowing tide. On the return, with the wind blowing fiercely enough to dislodge the hats on the heads of two of the men in Jones’ boat, a wave caught the craft broadside on and instantly capsized her. Jones was able to swim ashore to commandeer another boat, the Pearl, for rescue work. On his return to the site, he managed to pull five of his seven passengers into the boat.

Of the other two boats, Lewis Edwards was able to safely land his passengers ashore. He then journeyed to the Pearl, where one of the women pulled from the water had already succumbed to hypothermia. Searching for the third boat, the men heard screams from the far off mid-river.

About a mile from the scene of the original mishap they found a woman, Miss Packer, clinging to a seat in the water. There were no other survivors from her vessel, that commanded by the student, Gray.

Robert Morris, one of the rescuers, described what they found:

I saw the body of a lady. She was dead. I lifted her up, and with help placed the body in the boat. We saw the body of another lady, dead, and in the river, and carried it to the boat. Ten yards further we saw a body of a gentleman. We fetched another boat and near this boat there was the body of another gentleman, and we put it in the boat.

We crossed the river to help Lewis Edwards to carry the bodies of another gentleman and a lady. Then William Jones saw the body of another lady in the water, and we placed it in the boat. We waited until the police came there. We had seven bodies.2

The county coroner convened an inquest the following afternoon. George Lowe Senior, Harold’s father, was appointed jury foreman. In his presence eight men were placed in one of the boats to test its seaworthiness and evidence was collected from the boatmen, survivors and those who had decided not to join the fatal expedition.

After 40 minutes’ deliberation, George Lowe returned the jury’s verdict. They found that each of the total of ten dead had been drowned though the swamping of a boat. They made several recommendations concerning the number of passengers to be carried in boats, the inclusion of a skilled boatman in each craft, and called for an inspector to warn people of the danger they incurred in boating on the estuary under conditions like those on the day of the accident.

The jury was unanimous in commending the actions of Jones after the accident, and of Edwards in landing his passengers and returning to assist. The details of the events that took place that summer day, the tragic deaths and the attempts of the boatmen to rescue the victims, would have a profound effect on the small community. Whether or not George Lowe discussed in any detail the evidence he had heard with his family, Harold was old enough to have heard for himself the mixture of facts and rumours surrounding what had happened out on the Mawddach.

The lives of George Lowe and his family were to be even more directly touched by a boating accident the following year. With Christmas just past and the New Year still to come, at teatime on Friday 27 December 1895, George Lowe Junior took his punt from where it was moored in Aberamffra Bay across the mouth of the estuary to Penrhyn Point, and then crossed back to Aberamffra. Later that evening, at about 5.30, he left the house to secure the punt, apparently in ‘good health and good spirits’. What happened next is a matter of conjecture.

The evidence submitted at the coroner’s inquest suggests that he missed his footing as he descended the quay to get into the punt and was pitched into the sea. Unlike his younger brother Harold, boatman George could not swim. His sister Ada raised the alarm between 9 and 10 p.m. The family first searched the grounds of Penrallt, and going down to Aberamffra could see the punt in what seemed its usual position. As the Lowes continued their late-night search through the town, one of George’s friends had an eerie experience.

Robert Morris, a boatman involved in the rescue efforts of the previous summer, was awakened about 1.30 on Saturday morning by someone knocking at the door. He and his brother came down to answer the summons, only to find themselves gazing into the empty night.

Morris, as he later told the inquest, could not shake the feeling that there was something wrong. Walking down the street he found Ada and Annie Lowe near the Barmouth Hotel, who told him that George was missing. Ada believed some mishap had occurred with the boat.

Morris went to Aberamffra. He could see George’s boat alongside the quay, attached by a single rope. Going to another vantage point, he spotted a body in about 3½ft of water. Morris’ brother Francis now arrived on the scene with Dr Lloyd and a boatman.

They stalked across George Lowe’s small punt to a larger boat from which they were in position to reach the floating corpse. While the other men balanced the boat Morris stretched out far and pulled the body in with a mussel rake.

PC Barnard, hastily summoned by Francis Morris, hurried up. The men moved the body onto a stretcher and then to the quay where Dr Lloyd examined it and found no wounds or bruises. Life had apparently been extinct for some five or six hours.

The men and distraught family members took George Lowe back to Penrallt. There were perhaps shades of Ham Peggotty in David Copperfield, with the drowned boatman being carried to the house after he was washed back to shore. That same afternoon an inquest was held at the police station. After viewing the body in the family home, the jury returned to hear evidence from Ada, Morris, Lloyd and Barnard. A verdict of ‘accidentally drowned’ was returned, and a vote of condolence passed for the bereaved family.

George Ernest Lowe had been a popular young man, known for his ‘gentle and sympathetic manners’, and his death was said to have ‘cast quite a heavy gloom over the neighbourhood’. The Victorian rituals of grieving were observed, the black-bordered mourning cards distributed to friends and relatives to mark his passing, and with a rector officiating at the house and graveside, a procession wound its way from Penrallt to Llanaber churchyard in several carriages. In spite of the heavy rain there was a large attendance of George’s friends, including many boatmen and choirboys who sang with ‘great feeling and efficiency’.3

What the thirteen-year-old Harold Lowe felt at the loss of his brother can only be imagined. Typically circumspect in discussing his own emotions, when speaking later about the event he would refer to the tremendous shock the death of an eldest son and namesake caused his father, who deeply mourned the loss. But Harold too felt distress and grief at the sudden bereavement, the severed happiness. His older brother, who had left the house hours before in the height of health and spirits, was carried home ice cold and still. George had been a skilled boatman, well liked and gregarious, only seventeen years old. Without warning, he had been snatched by the sea. It was a lesson the quick and impressionable adolescent Harold did not forget, but it did not prevent his testing himself against the same elements.

Given his later career and Titanic association, it should come as no surprise that the earliest anecdotes of Harold Lowe centre on childhood exploits involving boats. The first recorded incident took place out at sea, with what might easily have been fatal results. On the afternoon of 14 September 1896, Harold took his father’s punt out from Aberamffra for a sail. It was, so the Barmouth Advertiser noted, ‘rather a risky thing to do considering his youth and the squally weather.’

When about half a mile out from shore, thirteen-year-old Lowe was struck by the boom and the boat capsized. Fully clothed and wearing heavy boots, he swam ashore and was, according to the Advertiser, ‘none the worse save for the wetting’. The incident entered local lore, to be recalled by Barmouth residents many years later after Harold had passed through another ordeal at sea.

The episode with the punt demonstrated his stubborn perseverance (and swimming prowess), but also showed how Harold’s physical courage could lead to recklessness. A woman who grew up with Lowe in Barmouth was later to claim that he had saved her brother’s life but in the process imperilled his own, although the exact details of this reported incident are elusive. Locally he was known to be a smart lad, but his role in another incident of note indicates that when mischief among the local boys was afoot, Harold Lowe was a ringleader.

It is recorded that he and a group of comrades took a boat far enough out to sea in dangerous weather that onlookers ashore feared they were in danger. The lifeboat Jones-Gibb was dispatched to the rescue. One can well appreciate the trepidation with which the boys watched the approach of the Jones-Gibb. Launching the lifeboat was no light matter, and when it was ascertained that the boys had occasioned a false alarm they could hardly expect to be popular with either the lifeboat crew or their own families. As the lifeboat finally pulled alongside, the insouciant Harold chimed in with the query: ‘Where are you bound?’ It was a touch of bravado that would later be the hallmark of many of Harold’s recorded remarks regarding an episode of high drama.

In the October following Harold’s misadventure in the punt, the town was lashed by a southwesterly gale and an unusually high tide that destroyed extensive sections of the sea walls, made the Marine Parade impassable, flooded houses, submerged Arthog and Barmouth Junction railway stations and destroyed fields and fences. In one stable a horse was found to be swimming in the inrush of sea. Businesses were shut, telegraphic communication cut off for one morning and railway traffic almost totally ceased. Barmouth’s townspeople feared for their family members at sea, and there was a rush of reassuring telegrams when the service was resumed. But when the weather had finally calmed and the assessment of the damage began, the receding waters left a sickening surprise. Washed ashore was the battered, headless body of a man. No identification could be made; the verdict recorded at the inquest was: ‘Found washed ashore on the beach in the parish of Llanddwywe.’ The nameless man was buried swiftly and quietly.

Harold cultivated other talents in childhood beyond his skill with boats. The Lowe boys were accomplished singers, an area in which the Welsh traditionally excel. Members of the Anglican Church, George Ernest Lowe had belonged to the choir of St David’s church, and his younger brothers Harold and Edgar sang in the choir of the grand, new St John’s church which stood high on the slopes where the town was built. Harold always took great pleasure in music and enjoyed singing, and the ‘Penrallt Boys’, as they were known locally, performed at small local entertainments and fundraisers.

With George’s passing Harold now assumed the role of eldest son, and with it came certain hopes and expectations. George Lowe seems to have been determined to give his sons the best education possible. In November 1897 the two eldest boys, Harold and Edgar, transferred from the 6th grade of the Barmouth Board School to the newer Barmouth County Intermediate School. By the standards of the day Harold Lowe received a very good education. Prior to the nineteenth century the Welsh education system had lagged behind that of the rest of Britain. It was rare for any child to be educated above the elementary level and in 1881 a departmental committee reported to Gladstone that only 1,540 children in Wales had received any kind of grammar-school education. The intermediate school encouraged bilingualism in the students, and use of Welsh as well as English was practiced. Although his family were Anglo-Welsh rather than native Welsh, Lowe was fluent in the Welsh language.