9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

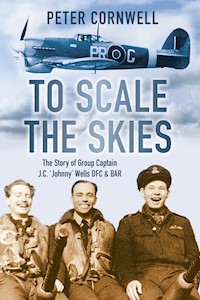

With humble beginnings as an RAF apprentice, Johnny Wells progressed to pilot and rose to the higher echelons of command at the Air Ministry. From idyllic pre-war training, he would fly bombers against rebels over Iraq, combat Fw190s over England in the newly introduced and equally dangerous Typhoon; he would undertake hazardous low-level anti-shipping strikes in the English Channel, as well as train-busting sorties over occupied territory at night and close-support ground-attack operations across northern Europe following D-Day. Indeed, Wells ended the Second World War as one of the most successful and highly decorated Typhoon Wing Leaders in the Tactical Air Force. This well-researched account of one man's rise through the ranks of the Air Ministry is finely illustrated with contemporary images and is an excellent testimony of what was required of air pilots during the Second World War. Wells' story is both an inspiration and a gripping account of one man's journey through a service career spanning more than three turbulent decades.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Abbreviations

Introduction

1Sheringham Shannocks

2Trenchard Brat

3Bircham Newton

4Tyro Pilot

5Middle East Air Force

6On Active Service

7Target Towing

8Flying Instructor

9Spitfire Pilot

10Duxford Typhoon Wing

11Frontline Manston

12‘Display’ Leader

13Staff Wallah

14Typhoon Wing Leader

15Peacetime Command

16RAF Gutersloh

17Station Commander

18Baghdad

Epilogue

Appendix I: Aircraft Flown

Appendix II: No 84 Group 2TAF

Bibliography

Copyright

ABBREVIATIONS

AA

Anti-Aircraft

A&AEE

Aeroplane & Armament Experimental Establishment

AC1

Aircraftman First Class

ADGB

Air Defence Great Britain

AFC

Air Force Cross

ALG

Advance Landing Ground

AOC

Air Officer Commanding

ATC

Air Training Corps

ATS

Armament Training Station

BAFO

British Air Forces of Occupation

BLPI

British Liaison Party Iraq

BOAC

British Overseas Airways Corporation

CBE

Commander of the British Empire

C-in-C

Commander-in-Chief

CO

Commanding Officer

DCM

Distinguished Conduct Medal

DFC

Distinguished Flying Cross

DFM

Distinguished Flying Medal

DSC

Distinguished Service Cross

DSO

Distinguished Service Order

ELS

Emergency Landing Strip

FAA

Fleet Air Arm

F/L

Flight Lieutenant

F/Sgt

Flight Sergeant

F/O

Flying Officer

FTS

Flying Training School

G/C

Group Captain

GCC

Group Control Centre

GM

George Medal

GOC

General Officer Commanding

HMS

His Majesty’s Ship

HQ

Headquarters

IO

Intelligence Officer

KCB

Knight Commander of the Bath

KD

Khaki Drill

LAC

Leading Aircraftman

MC

Military Cross

MEAF

Middle East Air Force

MM

Military Medal

MO

Medical Officer

MRCP

Mobile Radar Control Post

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

NCO

Non-commissioned Officer

OBE

Order of the British Empire

OC

Officer Commanding

OHMS

On His Majesty’s Service

ORB

Operations Record Book

OTU

Operational Training Unit

P/O

Pilot Officer

QBI

Signal code for bad weather

RFC

Royal Flying Corps

RLG

Relief Landing Ground

RM

Royal Marines

RN

Royal Navy

RNAS

Royal Naval Air Service

RNR

Royal Naval Reserve

RNVR

Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve

R/P

Rocket Projectile

R/T

Radio Telegraphy

SAO

Senior Administration Officer

SASO

Senior Air Staff Officer

SFTS

Service Flying Training School

SITREP

Situation Report

S/L

Squadron Leader

2TAF

2nd Tactical Air Force

TUC

Trades Union Congress

UN

United Nations

USAAF

United States Army Air Force

USAF

United States Air Force

VE

Victory in Europe

VHF

Very High Frequency

WAAF

Women’s Auxiliary Air Force

W/C

Wing Commander

W/O

Warrant Officer

WRAF

Women’s Royal Air Force

WSM

Wing Sergeant Major

W/T

Wireless Telegraphy

INTRODUCTION

This book owes its existence to a chance conversation between two schoolboys and the fact that the father of one subsequently recognised a photograph of a celebrated goat among the souvenirs of an RAF pilot. First thanks are therefore due to my good friend John Vasco and his son Jamie for bringing the collection of the late Johnny Wells to my attention and for introducing me to his niece, Mrs Margaret Goff.

With her permission, I was allowed to inspect a wealth of documents, photographs and material relevant to Johnny’s RAF career that remained in the keeping of the family. While his meticulously compiled logbooks revealed a rich source of information on his varied flying experiences, his surviving letters gave an equally fascinating insight into the character of the man himself – a rich vein of material further enhanced by his wide selection of photographs. For allowing me full access to all of this, copying me dozens of documents and answering my many questions, I am most grateful. Margaret Goff has been most generous with her time and enthusiastic in her support of the project from my first hesitant suggestion that she might consider entrusting me with the biography of her late uncle. I can only hope that she feels that I have done his story full justice.

Given this prime source material, any gaps in the family records were more than adequately filled by documents held in the National Archives at Kew and by selected published works as acknowledged in the bibliography. But for personal memories and anecdotes to flesh out the often sterile official accounts and add considerable colour to Johnny Wells’ story, I am indebted to some of those who knew him and flew alongside him. For their time and most generous hospitality whilst sharing memories of the man and their shared experiences, and for answering my questions, I am therefore grateful to: the late Wing Commander Roland ‘Bee’ Beamont, CBE DSO* DFC* DFC (USA) DL FRAeS; the late Squadron Leader Lawrence ‘Pinky’ Stark, DFC* AFC; Flight Lieutenant Sir Alec ‘Joe’ Atkinson, KCB DFC; and Flight Lieutenant Sydney ‘Darkie’ Hanson, MBE. Others who also provided valuable assistance were Peter Brookes of the Sheringham Museum; Jim Earnshaw of the No 609 (West Riding) Squadron Association; and fellow aviation historian Chris Goss, whose extensive photo collection once again proved invaluable. I thank them all.

My old friend and mentor, the late Bruce Robertson, generously cast an editorial eye over the completed text and offered several helpful suggestions. He also offered many photographs from his extensive private collection depicting aircraft flown by Johnny Wells during his early career. I was pleased to have had this final opportunity to once more share time with one of the founding fathers of the British aviation historian movement and regret that he did not see it reach fruition.

Peter Cornwell

Girton, Cambridge

May 2011

1

SHERINGHAM SHANNOCKS

Yellaway, yellaway, hear me great loud rattle,

Fly away, fly away, never more you’ll settle

Norfolk children’s rhyme

John Christopher Wells was born on 28 May 1912, in Sheringham on the north Norfolk coast; sea air in his lungs and salt water in his veins. The latest addition to an unbroken line spanning more than four generations of Norfolk fishermen, he was the youngest of three children, his sister Margaret being six years older and his brother Robert three.

Under normal circumstances, Johnny would have followed in his father’s footsteps, and those of his grandfather and great-grandfather before him, by becoming an inshore fisherman. But he was a ‘Mad Shannocks’, as tradition along this wild stretch of coast labels those who are Sheringham born – for their ‘shannying’ or wild and reckless risk-taking, and born into a period of great social and economic upheaval. And with such change comes fresh opportunities and challenges. Dragging a mean and perilous living from the cruel North Sea was not for him. He would break with family tradition and choose a different element to shape his life. He would take to the air.

He grew up in Lower Sheringham, a popular seaside resort a few miles west of Cromer, set ‘’twixt sea and pine’ as described in the publicity posters of the day. The neighbouring parish, Upper Sheringham, sheltered from the on-shore breezes a mile further inland, had a neat cluster of grey stone cottages set around All Saints church and the adjacent tavern. Surrounded by gently rolling hills and thick woodland, Sheringham sprawled between grassy, gorse-covered cliffs rising a hundred feet or so above its wide, sandy beaches. Eastward, the coast curved away towards Cromer, while from Sheringham Leas, high above the western promenade, the horizon was dominated by the sweep of Blakeney Point 10 miles to the west along the coast.

Sheringham, a quiet, relaxed place, shunned the blatantly vulgar displays and fairground attractions of other resorts. Yet despite more than a whiff of gentile pretension on the sea air, it had a particular charm which held its visitors in thrall and was in essence a modest little town offering an honest and hearty welcome.

Little has changed there over the years. The High Street slopes gently down towards the seafront from the Victorian railway station alongside the main road to Cromer. And at a fork in the road, just down from St Peter’s church, a squat clock tower sits in the shadow of buildings whose upper storeys are decorated in the mock-Tudor style so favoured by Victorian builders. Further down the street, at the lower end of town, a quaint jumble of grey pebble-built cottages crowd the seafront, all connected by a maze of alleys, cuts and closes, interspersed with shops, inns and boarding houses. A coastguard station and two lifeboat houses completed the picture-postcard scenery.

Heavy wooden window shutters are still fitted to most seafront properties, for winters here can be bleak. Biting North Sea winds and fierce storms, which in Johnny’s youth were constantly undermining the cliffs, force those foolish souls who do venture outside in such weather to stay well wrapped up, with teeth clenched tight against the wind. But during the long, hot summer months, the local population of around 2,000 or so was swelled by swarms of visitors descending on the village by road and rail. The Midland and Great Northern Railway, King’s Lynn to Norwich line, provided a good connection, via nearby Holt, to the quaint Hornby Dublo-like platform of Sheringham Halt.

Apart from this seasonal influx of visitors and the lucrative holiday trade, most of the local community gained a living from farming the acres of wheat and barley fields surrounding the village. Many harvested the sea. Like most towns and villages along this stretch of the Norfolk coast, Sheringham boasted its own fishing fleet with close to 300 boats and fishing smacks in its heyday. When Johnny was born, fishing was already in decline and the local fleet had reduced to about 75 boats and some 120 fishermen.

But, depending on weather and season, the fishing here could still be good with large catches of codling, skate, plaice, mackerel and herring being landed. The noise and bustle of boats competing to land their catches on to beaches festooned with wet sails, ropes and nets would have been familiar to young Johnny. Growing up in a family which owed its livelihood to the sea, he was often found playing amongst the wicker baskets and wooden boxes which littered the high water mark, crammed with crabs, lobsters and whelks en route to markets in Norwich and London.

Only a handful of the Sheringham fleet were luggers fitted for deep-sea fishing, most being in-shore boats like that operated by Johnny’s father, John Cox Wells, a third generation fisherman. Most of his catch went straight to the family fish shop in town, Grice’s, owned and run by his wife Mabel’s family.

The Grices were another old Sheringham fishing family, Johnny’s maternal grandfather, Robert Henry Grice, being greatly respected in the town. He owned the fish shop and was an elected member of the Urban District Council as well as being town crier, and served on the Sheringham lifeboat, the Henry Ramey Upcher. He also represented the town on the Eastern District Sea Fisheries Committee.

Another of Mabel’s relations was a prominent member of the Fishery Board, serving aboard the vessel Protector. So Johnny’s home life was dominated by talk of the weather and of the sea, and the house cluttered with bulky clothing, oilskins, sea boots and all the other paraphernalia associated with boats and fishing. His mother, a resolute and determined woman, did insist on keeping things neat and tidy and would spend hours trying to get the smell of fish off her hands before attending church every Sunday.

The Wells family had been fishermen and landowners on this coast for as far back as anyone cared to remember. Family folklore had it that years before, Johnny’s great-great-grandfather had made a tidy sum selling land to the famous landscape artist Repton when Sheringham Park was being created for the Upcher family. Exactly what had happened to this fabled fortune was unclear, but through a series of inter-connected wills over the years a distant relative, a solicitor in Norwich, inherited most of it.

The sea had taken Johnny’s great-grandfather in 1863, lost overboard and drowned at the age of 27, leaving a young widow with children to raise – a common enough occurrence in any fishing community in those days. Families who depended on the sea for a living were used to enduring such tragedies and many a child in Sheringham was raised without ever knowing a father.

Grandfather, John Philip Wells, another well-known local character and fisherman, had survived years at sea to settle into fairly comfortable retirement on an income largely derived from letting holiday apartments in the village. With the Grand Hotel and every other accommodation in the neighbourhood often full to overflowing during the summer months, this was a useful sideline for many local families and Johnny’s grandfather advertised holiday apartments during the season. For years, Elim House, his property in Mill Lane, was a favourite holiday haunt for many families of ‘regulars’.

With father often away at sea and mother busy in the fish shop, Margaret, Robert and young Johnny, were looked after by Dora Farrow, a distant cousin on their mother’s side of the family. Throughout their early childhood Dora cared for the children as if they were her own and they all loved her dearly. But when Johnny was about 7 or 8 years of age, the family moved to Grimsby leaving Dora behind. It was an awful wrench for all of them.

Grimsby offered their father the chance of working the big deep-sea boats, which may have lacked the independence of running his own boat but carried none of the associated costs. It was a move borne of necessity. Times were very hard and there was little money to spare, particularly during the hard winter months when fishing often proved impossible due to the weather. The lure of a better, more reliable income proved irresistible. But before long it became clear that things weren’t working out as planned and by 1922 the fiercely independent Mabel had had quite enough of Grimsby and her increasingly unreliable husband and she returned to her family in Sheringham with the three children.

They quickly settled back into the familiar routine of Sheringham life with its close-knit community. Most families here were interrelated over generations so they were surrounded by family and friends. To make ends meet, Mabel went back to what she knew best and opened another fish shop in West Runton, on the Cromer Road.

The children all attended the local council school where Johnny, always a bright and inquisitive child, emerged as a star pupil, regularly topping his class year after year. But once school was over he was as adventurous and playful as any boy his age, a popular playmate with a wide circle of friends, and a frequent patron of the cinema down the Cromer Road where he regularly surrendered his hard-earned coppers. With a shock of fine brown hair and bright hazel eyes, he grew up an active and athletic boy who never walked anywhere if he could get there by running, and would happily spend hours exploring the local countryside or playing on the beach with friends. He blossomed mentally and physically and shot up in height, soon outstripping his elder brother Robert.

On warm summer evenings, he was probably one of the dusty young urchins who would squat on the kerb outside the open-air theatre at Arcade Lawn to ogle the ‘toffs’ from the hotels along West Promenade who arrived in all their finery for the concert parties, attracted by popular entertainers of the day such as Leslie Henson, Jack and Claude Hulbert, or Cicely Courtnedge.

He grew up in a loving and affectionate family, mother and children remaining very close throughout their lives. Mabel raised them to cherish virtues she had been brought up to value herself: honesty, integrity and probity. The Grice family was full of people to look up to and take pride in: relations, however distant, who inspired great respect and deep admiration in young Johnny.

Meantime, Johnny’s father stayed behind in Grimsby trying to make a living. He was away, often for days on end, far out in the North Sea, and contact with the family back in Sheringham was at best sporadic. Inevitably they became increasingly estranged and he soon became a background figure, rarely mentioned or discussed, particularly within earshot of the children.

On the face of it, there was little or nothing in Sheringham that would fuel a young boy’s imagination or spark any interest in flying. For sure, Johnny would have known all about ‘the first German bomb to fall in England in World War I’ which had dropped in Whitehall Close, off Wyndham Street, early in the Great War. But this stray missile from Zeppelin L4 in January 1915 was surely scant reason for him to decide on a career in the Royal Air Force.

Did he, perhaps, on a hot summer’s day lie up on the cliffs watching the occasional aircraft drift high overhead, the murmur of its engine merging with the hum of insects and the dull roar of the surf? Did he ever ride his treasured bicycle the 6 miles or so along dusty lanes to the nearest airfield at Holt? Here a landing ground had been established during the Great War as a satellite to the RNAS air station at Great Yarmouth and Zeppelin chasers had been based. But Johnny would have found no trace of them remaining and the grass knee-high.

The reality is probably far less romantic. In May 1926 Johnny would have been 14 years old, which was school-leaving age. That same month the TUC called a general strike in support of the coal miners and 4 million workers downed tools. The tottering British economy was in serious trouble. Employers and successive governments alike had failed to tackle rising taxation and the crippling costs of the First World War, and workers were ill-prepared to sacrifice hard-won improvements in their working conditions and living standards. A period of economic doldrums threatened which would last a decade and continue well into the 1930s. Prospects for a young lad about to leave school were bleak indeed.

Many head teachers, aware of the opportunities presented by the RAF Apprenticeship Scheme, actively encouraged lads with good educational standards and the necessary aptitude to consider the RAF for a future career. So it is highly likely that an approach from his headmaster, Mr S.E. Day, was how Johnny and the family first came to learn of the exciting possibility of an RAF apprenticeship.

Estcourt Day, headmaster of Sheringham Council School, was the source of great encouragement and support to his young student, offering sound advice and good counsel to the family which undoubtedly helped them reach certain decisions concerning Johnny’s future. He also provided this glowing reference:

It gives me great pleasure to testify to the splendid character of John Wells late pupil of my school. During the last twelve months of his school career Wells was senior boy and as such held positions of responsibility and trust. Throughout I have always found him honest, straightforward and trustworthy. He has always been most punctual, keen on his work and most willing to oblige. In 1925 he was awarded the Character Prize for the school, this being the result of voting from his own school fellows. I have no hesitation in recommending him as a youth of high moral character and feel sure he will do his duty thoroughly and willingly wherever he is.

S. Estcourt Day, Head Master.

It must have seemed like a godsend, as there was a growing awareness within the family that Johnny should avoid going to sea like so many of his forebears. He was gifted and bright, and, whilst it was probably never discussed openly, everyone accepted that young Johnny could have a bright future ahead of him. Besides, it was a very flattering thing for Johnny to be recommended so highly by his headmaster, a fact that an immensely proud mother would have undoubtedly shared with those who enquired after him in casual conversation over the shop counter.

Luckily, Johnny’s elder sister and brother were both bringing money into the household, making it a lot easier to entertain any future for young Johnny beyond that of simply earning a living. Equally bright, his sister Margaret had quit school at 14 years of age to start work to help make ends meet and bring some extra money into the household purse. His brother Robert had a post round and worked alongside their mother in the fish shop, as well as a weekend job lighting the fires in Beeston church before services.

With the economy in the doldrums, the armed services were one of the few avenues which still offered a young man a decent chance of a career. They would even teach you a useful trade. Hadn’t one of Johnny’s uncles on his mother’s side, John Edmund Grice, done well for himself in the Royal Navy? Joining as a boy cadet, he had served aboard HMS Princess Royal during the Great War, rising to become the youngest warrant officer in the service. Rumour had it that he would soon be commissioned as an officer which was some achievement for a Sheringham lad, educated at the local school, but it just went to show what was possible.

So, with Mr Day’s help, the necessary application forms were completed and sent off. A prompt acknowledgement duly arrived. There was a stiff entrance examination to be taken, consisting of two three-hour papers. According to his mentor, Mr Day, of the 500 or so boys who would sit the examination across the whole country that June, only the top 200 would be selected. So extra coaching was the order of the next few weeks. Finally, the great day came, and although Johnny felt that he had done his best and was quietly confident, it was a tense time awaiting the results.

In due course a buff OHMS envelope fluttered through the letter box and with fingers trembling with excitement and anticipation, Johnny tore it open. Anxiously he scanned the contents trying to make sense of it all. He had to read it twice before the truth dawned: A list of successful entrants to the ‘Limited Competitive Examination for the Entry of Aircraft Apprentices’ included his name. He was placed 103rd out of 467 and had ‘gained entrance to the RAF Apprentice School at Halton’. Delighted at his success, Johnny was nevertheless a little surprised at his somewhat humble rating after enjoying top place at Sheringham Council School for so long. Clearly he was moving up a grade and would need to buckle down to some serious study to stay in the race. But as his mother was quick to point out, many of the other successful applicants came from prestigious sounding schools or even technical colleges. He was to report within the week and a travel warrant and joining instructions were enclosed. He was to be an airman.

2

TRENCHARD BRAT

On 31 August 1927, 561960 Boy Aircraft Apprentice John Christopher Wells, along with 300 or so other would-be erks, arrived at a small railway station in rural Buckinghamshire en route to RAF No 1 School of Technical Training at Halton.

Alighting from the train, they were greeted by a loud-voiced flight sergeant who checked their names against his list and shepherded them all into waiting trucks for the journey to Halton, about 4 miles from Aylesbury amongst the rolling Chiltern hills. Bouncing around in the back of the lorry, Johnny viewed the passing scenery with interest. It was decidedly different to the wide horizons and levels of his native East Anglia.

On arrival at Halton, Johnny found himself allotted a member of ‘C’ Squadron, in No 4 Apprentices Wing. They were harried into groups and formed up on the grey tarmac parade ground facing a flagpole flanked by an anti-aircraft gun, a relic from the Great War. The RAF standard fluttered weakly in the breeze. Blank windows of the tall, red-brick barrack blocks surrounding the square gazed down on them. Suddenly, they were all feeling strangely subdued, out of place and very, very civilian.

After a few words of welcome from an astonishingly immaculate officer who turned out to be the CO, Wing Commander W.C. Hicks no less, they stomped off to be medically examined and were then sworn in as aircraft apprentices – no turning back now.

Next they were issued with mattresses, blankets and pillows, directed to their dormitories, and shown how to make up their beds. Then, a brief tour of the ablutions: heavily disinfected toilets and a long washroom with rows of taps and bowls down one side and open shower cubicles opposite, before adjourning to the mess hall for tea. Here they queued at the serving hatches for bread and margarine with a dollop of jam, a slab of fruit cake and a steaming cup of dark brown tea drawn from enormous urns and served in thick china mugs emblazoned with the RAF crest. Perched on a bench and jostling for elbow room at one of the long mess tables, Johnny munched his way through it amidst the excited chatter around him and reflected on his introduction to service life. So this would be home for the next three years – not bad at all!

The following morning, after reveille at an obscenely early hour, they stumbled through ablutions and off to breakfast. Two lads from each mess table collected what was on offer from the kitchen hatch, carried it back and dished it out to the others with much hurried passing of plates and ribald comments on the size of some portions which came under close scrutiny. Suitably fortified, everyone was then ushered to the barber’s shop from where they emerged a little later like shorn lambs.

Next the clothing store, where they shuffled along in front of a counter to be issued with uniforms: breeches, puttees, boots, high-necked ‘choker’ tunic, peaked cap, stiff overalls, socks and underwear – the lot. Most things were issued in threes: one to wear, one to wash and one spare for kit inspection, which added considerably to the overall bulk. On top of which came a bewildering assortment of boot brushes, cleaning kit, plates, mug, knife, fork and spoon, webbing, towels, their very own bath plug, and a huge kit bag to carry it all.

Staggering under the load, they returned to their billets and changed into uniform, swapping items of clothing with one another in an effort to find something that approximated a decent fit. Struggling into coarse, unfamiliar uniforms was an uncomfortable yet exciting experience for the young apprentices. Civilian clothes were parcelled up and addressed home before they expectantly viewed results. They were starting to look something like proper airmen, ‘with most artificial waist and more artificial chest and rump’ as Johnny described himself, though most still felt and certainly looked distinctly less than military.

An inveterate correspondent, Johnny wrote regular letters to his sister Margaret back home in Sheringham throughout his time at Halton. Every week or so he would describe his latest adventures and, fortunately, many of these letters have survived. They provide fascinating insights into his character and his impressions, with often graphic descriptions of the typical experiences of a Halton apprentice in the late 1920s. Written in his characteristic neat, confident hand, they display obvious affection, a keen sense of observation, and a wicked sense of humour.

Obviously one early mystery, that of winding unfamiliar puttees around calves, took hours of practice to master amidst much hilarity. But like everything else at Halton he soon got used to them:

Some poor laddie got into a terrible mess with his putees. Somehow he wound them round both knees and after tugging first one end and then the other for half an hour he finally finished with half of them round his neck and was in danger of slow asphyxiation. Beastly things puttees. They are put on so tightly that when at last I staggered back to the barracks and removed them from the shanks, the pins and needles arrived by the truck.

The RAF, or more accurately its predecessor the RFC, had been at Halton since 1917 when it took over a military site there as a training centre. But not until plans were being finalised for the future of the post-war RAF did the concept of Halton fully emerge. It was the brainchild of Hugh Trenchard, the ‘father of the RAF’, who in 1920 announced plans for an Aircraft Apprenticeship Scheme for boys of good education and physical fitness. Under this scheme, boys 15 to 17 years of age would sign on for twelve years’ regular RAF service, the first three of which would be spent at Halton being trained as ground technicians and tradesmen. No 1 Apprentice Wing, with 1,000 entrants, first formed there on 22 October 1925 and regular intakes had followed ever since, Johnny joining the sixteenth entry.

Halton was a huge complex of buildings and it was not long before Johnny and his new chums were off exploring their surroundings and looking around:

I had a squint inside the school on Saturday. Through one doorway labelled ‘Lab’ I espied a queer chunk of engineering which seemed to suggest weird and wonderful evolutions, however we could not investigate on the spot … We next trailed into the lecture hall, an imposing room with tiers and tiers of seats towering skywards, all nicely carpeted and distempered in bale buff and dark brown, and with a white dome. We gaped into the maths rooms which looked so dry that we retreated to the hockey pitch where we maimed each others’ legs with painful hard hockey clubs and a much harder ball.

Their first few weeks were spent in learning basic drill and settling into the disciplines of service life: reveille at 0630 hours, ablutions and a quick cup of cocoa, before falling in outside the barrack blocks in shorts and singlets for thirty minutes’ exercise. Come rain or snow, the physical training instructor kept them on their toes until they glowed – then a most welcome breakfast, often the best meal of the day. After that, following daily routine orders, there was inspection by the duty officer before a period of hearty drill under the steadfast gaze of Wing Sergeant Major Lea – irreverently known to all and sundry as ‘Annabelle’.

Most of the senior NCOs were ex-Brigade of Guards, recruited to lick the infant RAF into shape, so discipline at the wing was harsh. Every Friday a dormitory inspection took place and woe betide any group who failed to reach the required standard; fatigues or loss of privileges were regular features of life at Halton. One of Johnny’s early letters home describes a fairly typical daily round:

We have had a strenuous day today and when we came off the square limp and fatigued everybody was blessing vaccination and unsympathetic Sergeant Majors. We have early meals here, brekker being at 7.00, dinner at 12.30 and tea at 4.30, so that by the middle of the evening we are famished and have to retire to the NAAFI where one Eccles cake cost 1 1/2d and an extra halfpenny is clapped on everything for luck. They are so mean that they take the wrappers off the Sharps Creamy Toffees because free gifts can be obtained from them. Some of the chaps are waxing eloquent over it because they are within fifty or so of the required 500 wrappers!

The workshop complex was vast, covering a few acres, with workshops adjacent to each other and set out in long rows. Here budding apprentices learned their trade, under Squadron Leader MacLean, and the work was painstaking, often literally so, but the atmosphere more relaxed than the discipline of the wing.

They were to spend the whole of their first year working on a solid block of cast iron learning several basic skills. One side of the iron block had to be filed flat, and two even parallel grooves cut down the centre. Then you had to chip away the ridges which stood proud as a result of all this effort and file the surface perfectly flat again. Working at crowded benches in a huge noisy workshop, young inexperienced hands wielded heavy hammers, files and surgically sharp chisels. The din was incredible and the resultant damage to fingers and knuckles had to be seen to be believed. Gradually the skills of measuring, marking off and working to fine limits of a thousandth of an inch were mastered.

During this period, preliminary tests were conducted to start assessing the suitability of each apprentice for selection to specific trades: airframes, engines, armament or transport. Johnny found himself earmarked as a potential engine fitter which suited him just fine. It seemed to have a lot more about it than simply patching and repairing airframes, although he had to admit that the armourer’s job had a certain appeal – handling bombs, machine guns, ammunition and the like. All very exciting and war-like.

Every afternoon, apart from Wednesday, was spent in the workshops learning technical skills whilst periods in the machine shop, welding shop, foundry, metal shop and blacksmiths further extended their technical knowledge. After a year mastering basic theory and practice, they were ready to transfer to the hangars to start work on the real thing.

Workshop schoolrooms conducted by experienced NCO fitters, many of them ex-naval engine room artificers and sporting dustcoats complete with stripes denoting their rank, were set up in each corner of the hangars. Here Johnny and his fellow engine apprentices were introduced to the baffling complexities of the modern aero engine, starting with the fundamental principles of internal combustion before moving on to the differences between in-line, radial and rotary engines.

The tutors knew their trade inside out and would pass on their knowledge to small groups of a dozen or so rapt apprentices, dressed in the obligatory overalls, who clustered around perched upon benches in front of the blackboard. Instruction was clear and questions encouraged at every stage and sessions were often enlivened with humour or some colourful anecdote culled from the instructors’ lurid past.

Sessions were interspersed with practical tuition, again done in small groups so that everyone got hands-on experience. Using motor engines at first, they progressed on to low-powered aero engines. They bench-stripped and re-assembled engine components and entire motors until they could practically do it blindfolded. Within a few months they were tackling major overhauls and refits. Gradually, they laid bare the mysteries of engines, carburettors and magnetos; superchargers and pumps; filters, fuel and hydraulic systems; and a myriad of other topics, until they were deemed proficient enough to graduate on to more modern high-powered radial and in-line aero engines.

Much of the training was done with engine in situ on the aircraft, which meant working in the open in all weathers. It was here that they turned theory into practice and started to gain the skills that would be required of them. Everything was done under the expert tuition and constant supervision of the instructors, some of whom, Johnny and his cronies soon learned, had barks worse than their bites:

Things are at the usual mid-term state. One ghastly engine (complete with final exam) just over. Tomorrow we start on our last – the famous Napier Lion. Naturally we change our instructors & we get a bull-necked Lancashireman – Wilkins by name instead of the long suffering Ware. I believe he is a happy soul & if he did not expect you to file to .0005” of arc dimension he would be alright. Anyway I have seen him laugh – so must be alright. Anybody who can face us & laugh has some innards!

We were put on washing down some machines & the day & water being very hot, interest in washing flagged somewhat, so a little liveliness was clearly indicated. The soft soap which we had been using … made lovely snowballs only slightly more odiferous & messy than self respecting snow. Still it stuck where it hit & that is the main thing. There were twelve of us altogether & three machines. The ensuing battle was exactly what you might expect & believe me was highly satisfactory from every point of view, which is more than can be said for the machines. After that … bootless & sockless we skidded nicely over the main planes in real Swiss style & rubbed in the superfluous soap. The next operation was washing it off so we tied huge dusters on our wamps & paddled to & fro from numerous water tubs all over the planes. Rinsing being the next process more water was brought, the dusters changed & more paddling ensued; the result being highly satisfactory to everyone & the planes a model of industry & energy. Altogether the ’drome course was a good time & we are very sorry to return to the old routine.

Many early graduates of the Halton Apprenticeship Scheme, on joining regular RAF units, were met with a degree of jealousy, suspicion or downright contempt by the more seasoned veterans serving in the squadrons. These ‘old sweats’, many of whom were approaching expiry of their service contracts, felt threatened by the apprentices’ higher educational standards and feared for their jobs. They dubbed the Halton boys ‘Trenchard’s Brats’, a disparaging put-down which the apprentices learned to accept willingly and later adopted with a perverse but fierce pride. After all, they were as steeped in the heritage of the RAF and as jealous of its traditions as those who had learned them the ‘hard way’. But attitudes began to change when the Halton apprentices’ knowledge and skills became self-evident to the most hardened sceptic. Yet even when they became widely acknowledged as the finest tradesmen in RAF service, ‘brats’ they remained and do so to this day.

As well as their technical training, general schooling and physical well-being, the day-to-day routine of squadron life made additional demands on an apprentices’ time with a variety of tasks and extra responsibilities.

I was on the fire picket last week. Exciting times! At 6.00 pm precisely last Friday when we had just put our weary rumps upon the forms in the dining hall, the fire buzzer buzzed. Instant commotion! Uproar! Then a ruddy blush for the door! In record time we hied across the square to the drill shed and grabbed the fire cart right heartily. Bill Hicks, the Wing Commander, rolled up ten minutes later and trailed up and down the bored ranks. It was only an alarm! Groans. The whistle went and we dashed back to the jolly old rations. As in duty bound, the fateful eight had to wait until the square was empty. Dolefully we rushed back to the feast. Alas snaffled – gone to the unknown! Starving we retired to the Naafi. Such is life!

An ambitious project undertaken by apprentices during Johnny’s first year was the construction from scratch of a full-size biplane. Once completed and test flown, it was handed over to the Halton Station Flight who maintained it in first-class trim and flying condition – as was to be expected. It became a familiar sight in the sky around Halton and a constant reminder to every apprentice of what could be achieved.

The following July, someone on the staff decided that it would be ‘an absolutely beezer idea’ to convert the biplane into a monoplane. This was another major undertaking but, as the instructors recognised, an excellent learning vehicle for those involved in the design, planning, drawing, construction, rigging and bench testing. It was a project that had the potential to cover practically the entire syllabus. Gallons of midnight oil later, with the conversion done, all the necessary flight tests completed and the Certificate of Airworthiness duly granted, there was much celebration. Only then was it announced to the astonished assembly of proud young apprentices that their new ‘Halton Mono’ was to be entered in the next King’s Cup Air Race!

In the weeks leading up to the big event, growing excitement and anticipation on the station approached fever pitch. The forthcoming race became the sole topic of conversation with endless discussions on the relative merits of each new entrant and their previous form. Newspapers were eagerly scanned and aviation journals scoured for any scrap of information. Meantime, the aircraft itself was lavished with attention, fine-tuned and streamlined to a standard hitherto only dreamt of. Confidence grew.

On the day of the race only a small select group from Halton were allowed to attend but news of the result preceded their return. Leading the race and only 2 miles from the finish, the Halton entry had run out of petrol and had been forced to land – literally something of a come-down, but a magnificent performance of which they could all feel justifiably proud. Or so it was said at the time.

On top of classroom theory and practical work, every apprentice had to attend a full round of instructional films, demonstrations and technical lectures, some of them delivered by leading experts in the field:

I had a perfectly ripping evening last week at a lecture on ‘Slotted Wings’ by Handley Page. The gathering was of course select & the front benches were eminent technical officers & others of like ilk. We were the back benchers. Brother Page ambled happily through his notes & slides (90% shown upside down) & then came the discussion – and the fun.

His first victim was a Squadron Leader of great renown who ’midst respectful silence asked a question about the air eddies over the upper surface of the planes wings & said they were most noticeable at a certain part. Brother Page armed with lengthy pointer & smirking broadly indicated a spot on the diagram & said, ‘You mean there?’ His Highness replied in the affirmative & then – ‘Well they don’t, it’s here!’ from H.P. pointing to another spot a yard away & grinning expansively. His Highness just sank down weakly upon his unsympathetic chair whilst we rocked & choked at his foaming dial.

Another ass from the centre of the assembly then got up sprightly & expounded at painful length speaking with his usual plummy voice. He wound up with great stress, lifting his eyebrows to soaring heights by way of effect. Dead silence followed this learned tirade & then H.P. said, ‘’Fraid I don’ quite git yer!’ The learned friend fairly gobbled, then grew gloriously red whilst guffaws that were nearly muffled arose from the back benches. Deflation finally set in & he sat down perspiring.

We began to take a lively interest at this point & by the time the lecture closed down we were shrieking at the answers thrown around to the learned by H.P.

Clearly an accomplished speaker, Handley Page obviously knew a thing or two about putting a message across and had gauged his audience to a tee.

Two days a week were also spent on school studies in order to raise apprentices’ standard of general education to at least matriculation level. Mathematics, science, technical drawing and English were drummed into them under the supervision of the headmaster, Mr H.A. Cox, and Sunday morning church parade punctuated each week, helping to keep track of the days, with religious services conducted in a converted hangar.

There was also a fairly regular stream of visiting dignitaries and foreign delegations, all keen to learn what they could of the RAF Apprentice Scheme in general and Halton in particular. Without doubt, it was an impressive facility and a much-admired jewel in the RAF crown. Over a single four-month period between March and July 1928, Halton hosted visits by the King of Afghanistan, the Czechoslovakian Air Attaché, a delegation of French officers and three officers from the Imperial Japanese Army. One of Johnny’s letters captures something of such occasions from an apprentice’s viewpoint:

We had our annual inspection by the AOC on Monday. We played at soldiers until 11am whilst the Wing band played a mournful dirge on bagpipes or bellowed brazenly from trumpets. They turned on some flutes by way of a treat (?) & that just about settled it. Had it not been for the OC persisting in saying ‘Flights florm flours’ it would have been a disaster.

But it was not all work and ‘bull’, for sports and physical education also featured on the syllabus. Of average height and build, Johnny stood 5ft 8in and enjoyed such activities, particularly cross-country running. Every Wednesday afternoon was set aside for sports, weather permitting, or even it seems when not:

Yesterday it rained Halton rain. It just fell. Consequently all games were off and some bright spark had an inspiration – X country. We set off and trailed down the Wendover Road for about a mile and two hills. Then we broke off and squelched happily up a morass labelled ‘Farm Road’ and waded muddily another ½ mile till we came to the worst hill in Bucks. It was chalk, it was wet, and it was raining Halton rain on the worst hill in Bucks up which we were supposed to run. Terrific groans.

We treadmilled up the skyline. It took ages. At last we reached the top and plunged into the wood, and incidentally more water. We wallowed through twigs and beautiful foliage. Knee-deep we emerged to the tipmost top (or topmost tip?). Then we had to descend. We did. A winding path led temptingly downwards covered by a carpet of brown autumnal leaves. Tempted, we rushed and we fell. The leaves were two feet deep and wet. The jolly old wamps kicked up the Persian carpet in a sloppy exhaust. I caught somebody’s wake and thirsted for revenge. I forged ahead and gave him my wake. Not ’arf. He was smothered. Happy, I continued. The gradient took its effect. My feet seemed to revolve. I tore my way through leaf and twig and arrived in record time at the bottom. A clear way lay ahead and I let it rip. I mowed ’em down like hay. I was done in when the Naafi gates heaved in sight and I staggered wetly upstairs leaving my trail as I proceeded.

Apprentices at Halton were members of a Flight within a Squadron, like the house system in public schools, and teams representing each Flight competed for the many sports cups and prizes to be won throughout the year. The better sportsmen amongst them could graduate to the squadron team, but only the very best of them stood any chance of qualifying to represent the wing. Johnny, a good runner, was less keen on other sports and this obviously included boxing:

We had a shriek last Wednesday. In the afternoon we all had to go and watch the boxing. After a time we felt bored … thus when we were told we had to watch it again the next night we groaned. At 9.00 pm feeling utterly fed up with boxing and boxers who were afraid to tap each other, we (my chum and I) trailed off and then turned in. At 11.00 pm the others turned up … we grinned happily from the jolly old blankets. The others raged. Tired as they were, the temptation to a pillow fight was not to be resisted. Therefore at 11.00 pm Room 6 was an uproar and after a strenuous twenty minutes we crawled back to bed and encored the efforts of some unhappy lads who were trying to make their beds, the lights having gone out at just after 11.15.

On 28 May 1930, Johnny, reaching the exalted age of 18, achieved ‘man status’ in the eyes of His Majesty’s Royal Air Force. His salary was doubled to a full guinea a week which undoubtedly helped with the cost of the cigarettes he was now officially permitted to smoke, although he had already been doing so for some time, risking a day’s detention had he been caught. After nearly three years in the service, to the vocal distress of his mother but barely concealed mirth of his sister, Johnny was also developing a very colourful vocabulary.

By now, Johnny and his cronies were old hands and fast becoming well versed in the ways of the service; younger, less experienced apprentices being considered fair game:

Here all the lamp-posts bearing fire alarms are painted with horizontal red & white stripes for half their height. Some wag told some poor innocent ‘rooks’ to line up at one for their first haircut indicating lamp-post to assure them that the adjoining building was the barbers. A doleful line accumulated its members patiently waiting for the doors to open. At last they did & the Wing Sergeant Major came in sight tapping belt in a satisfied manner. His brilliant optics then lighted on the line in front of him & popped out of his head in the approved manner. A minute of vain gurgling & this dignitary then quietly enquired what they wanted outside the Sergeants Mess!

The timid line having restored themselves to their feet after the polite enquiry replied ‘Haircuts’ in various keys & tones. The WSM then developed a mild fit for he landed the first one a beauty & then carried on moving down the steadfast though wavering line in record time. The line needless to say soon dispersed & melted gradually & painfully away whilst the WSM hitching pantaloons & belt made his way to his car.

Now WSM ‘Annabelle’ Lea was inordinately proud of his motorcar, which Johnny describes as a ‘super extra-special two-seater coupe sports model’, a source of considerable interest and amusement:

It was bought expressly to do one of the officers in the eye as (he) has just got a rare saloon car which quite outdid the WSM’s Fiat. Now the WSM’s car is glorious to look at but makes a terrible row when the engine is going. When Symington (Flt Lt Archibald Symington MC) first got his the WSM drew up in his Fiat pretty silently & viewed the other car with the eye of the owner-driver, noting polished black leather covering etc etc. His engine purred happily away & he asked the other respectfully when he was going to start his engine at which Brother Symington grinned & glided happily away. The engine had been going all the while! Curses from the WSM.

The WSM however gets this latest creation, a Hillman, in reply & we are waiting to see what his rival will do. I think the WSM has bitten off a big bit this time because the rival happens to be Symington of the soup family & has thousands of quids laying around as a matter of course. Yesterday he had his Hillman engine running & Symington told him to ‘shut off that damned row’. More curses from WSM which of course are just what we like. I don’t know what he will do if Symington rolls up in a Rolls on Monday.