18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

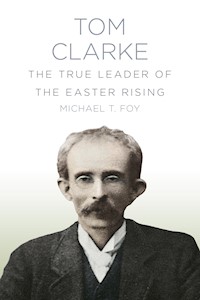

Long overshadowed by fellow republicans Patrick Pearse and James Connolly, Tom Clarke was the man who made the Easter Rising possible. During an extraordinary life dedicated to Irish freedom he rose from humble origins and endured thirty years of struggle, imprisonment and exile before becoming a master conspirator in the Easter Rising. Endowed with a charisma and moral ascendancy, he held together a disparate group of followers and they, in turn, recognised his indispensable leadership by insisting that his name alone should have pride of place on the Proclamation. It was a gesture that, in a sense, guaranteed Clarke immortality; it also proved to be also his death warrant. But death held no terrors for Clarke who was to die satisfied in the belief that, with the sight of a tricolour flying over the GPO, he had changed the course of Irish history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

1. Beginnings: Tom Clarke, 1857–1883

2. ‘An Earthly Hell’: Prison 1883–1898

3. Exile: America 1900–1907

4. Climbing to Power: 1908–1914

5. On the Road to Revolution, Part One: August 1914–September 1915

6. On the Road to Revolution, Part Two: September 1915–April 1916

7. Prelude: Holy Week 1916

8. The Easter Rising

Bibliography

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Once again I have to acknowledge the invaluable contribution of my friend and former colleague, Walter Grey. Besides our many enjoyable discussions about Tom Clarke, Walter read various drafts of the book and made many constructive suggestions for improvement. I am forever in Walter’s debt. I also want to thank my oldest friend, Dr Brian Barton who suggested that I write a life of Tom Clarke. Dr Timothy Bowman, Dr Michelle Brown and Stewart Roulston read and commented on the book’s final draft. I also received important help from Liam Andrews, Ken Boden, Lisa Dolan, Rev. Barbara Fryday, Gerry Kavanagh, Colette O’Daly and John Tohill. Once again I am indebted to Helen Litton who indexed the book. I would also like to express my gratitude to three members of The History Press Ireland: Beth Amphlett who commissioned the book, Ronan Colgan, and Gay O’Casey who edited the text.

Michael T. Foy

1

Beginnings: Tom Clarke, 1857–1883

In the year 1847 when much of rural Ireland was in the throes of the Famine, a 17-year-old farmer’s son from Co. Leitrim joined the British Army. For James Clarke that was not an unusual choice as a member of the small, scattered Protestant minority near the western fringe of Ulster and loyal to the British connection. Seven years later as a soldier in the Royal Artillery he was fighting in the Crimean War at the battles of Alma and Inkerman and taking part in the siege of Sevastopol. After the conflict ended in February 1856, his regiment transferred to Clonmel, Co. Tipperary where James was promoted to bombardier.

In Clonmel James met Mary Palmer, a Roman Catholic servant girl. On 21 May 1857 they married in Clogheen at Shanrahan Anglican parish church. Like many of her social class at the time, Mary could not read or write and made her mark in the register. Since in that period the Church of Ireland – to which James belonged – alone issued marriage licences, Roman Catholics like Mary often married under its auspices, though she insisted that any children the couple had would be raised in her religion.

Thomas James Clarke, the subject of this book, was their firstborn. Hitherto it has been accepted that Thomas was born in 1858 at Hurst Park Barracks on the Isle of Wight where James’s Royal Artillery regiment was stationed at the time. One historian, though, has asserted that Thomas was born at Hurst Castle – an abandoned fort on the Hampshire coast that had not had a military garrison for over 150 years and which during the eighteenth century had become a favourite haunt of smugglers. But the records show no Thomas James Clarke born on the Isle of Wight or in the nearby county of Hampshire during the entire 1850s, nor is anyone of that name listed in the British Army’s births and baptisms for England and Ireland during 1857 and 1858. Furthermore, Clarke’s widow Kathleen asserted that her husband had been born on 11 March 1857 and celebrated his fifty-ninth birthday just before the Easter Rising in 1916. The inference is that Thomas James Clarke must have been born out of wedlock in Co. Tipperary.1 Over the next twelve years, James and Mary had three more children – two girls, Maria and Hannah, and a younger son, Alfred. In April 1859, James, Mary and their then only child Thomas accompanied the regiment to South Africa, almost drowning on the way when their ship was involved in a serious collision.

After five and a half years the Clarke family returned to Ireland and, after being honourably discharged from the Royal Artillery in January 1869, James joined the staff of the Ulster Militia Artillery. With no married quarters available in the militia barracks, James and his family lived in Dungannon, a rather drab provincial town in Co. Tyrone whose arid social life came to a dead stop on Sundays. Evenly balanced between Protestants and Catholics, the town was dominated by its centuries-old sectarian struggle between Unionism and Nationalism. Tyrone had been a cockpit of religious and political antagonism since the Ulster Plantation and the county was also a heartland of the great O’Neill clan that in Tudor and Stuart times had provided two notable rebels against English power – Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone and his nephew, Owen Roe. This bitter county was the centre of Thomas Clarke’s small world. Only the newspapers connected him to outside events and he travelled little, apparently never even visiting Belfast, 50 miles away.

Now known universally as Tom, Clarke attended St Patrick’s National School in Dungannon. Under the monitor system he became an assistant teacher but was eventually let go because of falling rolls. Clearly intelligent and well read, Tom became an enthusiastic amateur actor in Dungannon’s Dramatic Club. But politics was his all-consuming passion and he came to espouse the cause of Irish independence. This commitment divided the Clarke family because his father had for decades served proudly as a British soldier and his brother Alfred had also enlisted in the Royal Artillery. Any early influence that his mother, who came from a very different background, might have had on Tom’s ultimate political beliefs remains a matter for conjecture. When James Clarke warned his son that defying the British Empire meant banging his head against a wall, Tom retorted that he would just keep going until the wall fell down. His rebelliousness was certainly not rooted in a miserable childhood. The Clarkes were a happy family and Tom respected and admired his father, rejecting only his army uniform; the bonds with his mother and siblings stayed strong and harmonious. Much more influential in shaping his political consciousness was Tom’s time in South Africa. Increasingly hostile to the British Army, he came to regard it as an imperial garrison that oppressed not the black population – then politically invisible – but the Boers, Dutch settlers for whom Tom developed a lifelong sympathy. But it was on his return to Ireland that Tom’s political ideas really crystallised. Only a few years after the Fenian Rising of 1867 the British Army and Royal Irish Constabulary were still highly vigilant – and visible – in Co. Tyrone. And in bitterly divided Dungannon memories of the Irish Famine remained vivid, while an agricultural depression during the late 1870s exacerbated a traditionally turbulent relationship between landlords and tenants. The town also experienced frequent sectarian rioting between Protestants and Catholics.

In 1878 Tom attended an open-air meeting outside Dungannon addressed by John Daly, a national organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). A superb public speaker with a powerful physique, imposing presence and magnetic personality, the 33-year-old Daly’s oratory mesmerised audiences and his vision of an independent Ireland left Clarke deeply impressed. Suddenly Tom realised that his mission in life was to destroy every vestige of British authority in Ireland – Crown, Viceroy, Army and the Dublin Castle administration, the entire colonial system. He espoused the same goal as Wolfe Tone, his greatest historical inspiration. Almost a century earlier, Wolfe Tone, the father of Irish republicanism and instigator of the 1798 Rebellion, had set out ‘to subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England, the never-failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country’. And from this goal Tom himself was never to deviate. Later in 1878, after the Dungannon meeting, Clarke and his best friend Billy Kelly joined a Dramatic Club excursion to Dublin where Daly swore them into the IRB.2 But after becoming the organisation’s Dungannon secretary, a disillusioned Clarke discovered that his idealised vision of the IRB as a sword for smiting England was very different to the drab reality of a society that had seriously lost its way. He was to spend the rest of his life remedying that situation.

Founded in both Ireland and America in 1858, the IRB was a secular, secret, oath-bound revolutionary movement dedicated to achieving Irish independence. Organised in circles, IRB members underwent clandestine military training, preparing to rise in Ireland when England became involved in a major war. Through conventional battle the IRB hoped to defeat British forces, establish a revolutionary government and win international recognition for an independent, democratic Irish republic. The IRB’s American counterpart – which became known as the Fenian Brotherhood – channelled men, weapons and funds to Ireland and after the American Civil War ended in April 1865, thousands of former Union and Confederate soldiers crossed the Atlantic hoping to fight in an Irish rebellion. But the British government struck first in September 1865 by arresting and imprisoning most IRB leaders and detaining hundreds more. This pre-emptive strike ensured that when the insurrection finally occurred in 1867, it was a complete anticlimax. The only significant action was at Tallaght outside Dublin, where police fired on and routed columns of rebels. After the abortive rising everything fell apart. With most IRB leaders in prison and the organisation itself bereft of energy and purpose, the Fenian Brotherhood collapsed into squabbling factions. By 1871 Prime Minister Gladstone believed it was safe enough to give an amnesty to the imprisoned IRB leaders, especially as constitutional nationalism was gathering strength in Ireland where a Protestant lawyer, Isaac Butt, had established a Home Rule movement.

One IRB leader, John Devoy, believed ‘it was a wonder that the men of the organisation, after such a series of defeats, had the recuperative power to reorganise the movement’.3 But somehow it did survive. However, to prevent another hopeless rebellion, the Supreme Council changed its constitution and stipulated that henceforth the support of a majority of the Irish people was required for the IRB to inaugurate war with England. In the 1874 Westminster general election, the Supreme Council even supported Home Rule candidates. But within three years this co-operation ceased as most IRB members became disillusioned with constitutional politics, though even then four Supreme Council members dissented and were forced out. So by the time Clarke joined the IRB in 1878, it was more like a talking shop than a revolutionary conspiracy. And when he finally got some action it proved sterile and self-defeating. In August 1880 a nationalist Lady Day parade through Dungannon led to clashes between Catholic and Protestant mobs in the so-called ‘Buckshot Riots’. A newspaper reported that after police in Irish Street fired buckshot into crowds, ‘the firing was returned with interest from revolvers and by repeated showers of stones from the crowds of desperate men, many of them inflamed by drink, almost rushing on the points of the bayonet in the eagerness of their attack’.4 Clarke and Kelly were among the shooters and despite eluding a subsequent round-up, the heat was on. Since Tom was already unemployed, they decided to leave for America, departing from Dungannon on 29 August 1880 and sailing a fortnight later from Londonderry. For Clarke this was a leap in the dark. But though it meant abandoning everything and everyone he knew, Tom was always a fearless gambler and no doubt hoped that in America his revolutionary career might finally take off.

After a fortnight’s voyage Clarke’s steamer arrived at Castle Garden on the island of Manhattan, then New York’s reception centre for European immigrants. Later many of them recalled the excitement of sailing up one of the largest natural harbours on earth and realising – even before its first skyscraper was built – that New York’s high-rise buildings promised them a new life in which the sky was indeed the limit. Pressing through a huge hall thronged with people conversing in many languages, Clarke was now a world away from Dungannon. Finally, immigration officials processed him and Kelly into a vibrant and astonishingly diverse metropolis of industry, finance, commerce and entertainment. This was the city that never slept. Here social life was exciting and liberating and iconic landmarks were everywhere from the Statue of Liberty and Broadway to Times Square and the world’s longest suspension bridge in Brooklyn.

By 1880 over a third of New York’s 1.5 million inhabitants were Irish or of Irish descent, concentrated mainly in the cheap housing of Brooklyn and Manhattan’s ‘Little Dublin’.5 Urban Protestant America regarded the Catholicism of the Irish as alien and subversive and many Irish slid into lives of crime, alcoholism and violence. Even though by the 1880s Irish immigrants like Clarke were much better educated than previous generations of illiterate peasants, many still worked at dirty, dangerous semi-skilled and manual jobs. With no waiting relatives or friends and lacking a house and job, Clarke and Kelly faced an uncertain future. But the New York Irish had stuck together, building a vast support network of social, military and athletic clubs, and it was through these that the pair came to board with another Dungannon man, Pat O’Connor. He also gave them jobs in his shoe shop, although after a couple of months they shifted to Brooklyn’s Mansion House hotel where Clarke worked as a storeman and Kelly as a boilerman.

However, politics was never far away and Tom and Kelly joined the Napper Tandy Club, a branch of Clan na Gael, then the leading republican organisation in Irish America. Founded in June 1867, the Clan was a revolutionary society committed to Ireland’s liberation by force of arms. It had only really taken off after January 1871 when Gladstone released IRB leaders like John Devoy, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and Thomas Clarke Luby and immediately exiled them to America. Joining the Clan, Devoy and O’Donovan Rossa quickly emerged as the dominant figures in Irish-American nationalism and in time both men would also dramatically change Tom Clarke’s life. Devoy’s forceful, single-minded personality and organising talent quickly attracted 15,000 members to the Clan from across America and in 1875 his fund-raising ability had persuaded the cash-strapped IRB to reunite with the American wing. A year later Devoy pulled off a sensational coup by dispatching a sailing vessel, the Catalpa, to rescue a group of transported Irish soldiers from a prison in western Australia. He then established a joint Revolutionary Directorate linking Clan na Gael and the IRB (with America the dominant partner). Devoy now stood at the zenith of his political power but ironically by the time Tom reached America in late 1880, Devoy had split the Clan and precipitated his own downfall. This was because Devoy’s triumphant Australian rescue had raised his followers’ expectations to completely unrealistic levels. Many outlandish ideas for attacking England now circulated, including a Clan submarine fleet that would destroy the Royal Navy and starve the enemy into submission. Devoy rejected all such schemes and dismissed as fantasy predictions of an imminent Irish revolution. Instead he favoured joining with Ireland’s landless peasantry and Isaac Butt’s Home Rule party in a broad national front that would campaign for gradual political and economic progress in Ireland. By 1880 this so-called New Departure policy had established an alliance between the Clan, Home Rulers now led by Charles Stewart Parnell, and Michael Davitt’s Land League.

However, this semi-constitutionalism went against Irish republicanism’s entire raison d’être of violent struggle against British rule. An authoritarian, Devoy had suddenly sprung his gradualist policy on a bemused membership, many of whom regarded it as heresy. Devoy’s leading critic and the champion of militarism was Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, a charismatic former IRB leader from Co. Cork. Once he and Devoy had been best friends until incompatible personalities and policies drove them apart. Studious, reserved and teetotal, Devoy was very different from the gregarious, chaotic O’Donovan Rossa, an alcoholic famous for his spectacular benders in Broadway bars. When O’Donovan Rossa’s atavistic hatred of England led him in early 1880 to advocate assassinating Queen Victoria and wiping out the entire House of Commons with chemical poison, Devoy expelled him from the Clan. But O’Donovan Rossa regarded Devoy’s policy as treasonous to the Clan and he didn’t go quietly, taking a minority of radicals with him. Even many members who stayed in the Clan harboured serious doubts about Devoy’s leadership. While his New Departure appealed to the head, O’Donovan Rossa’s demand for immediate, violent action to humiliate England appealed to the heart. In any struggle for the republican soul, Devoy was ultimately bound to lose.

After establishing his own radical organisation, the Skirmishers, O’Donovan Rossa set out to literally blow Devoy’s ‘heresy’ to pieces.6 He recruited volunteers and solicited funds for a bombing campaign in England that would embrace an openly terrorist strategy of ‘indiscriminately, deliberately, recklessly and uncaringly destroying civilian life, property and security in the pursuit of military and political ends. Randomness and ruthlessness are intended to sap confidence in the state, to create irresistible pressure on the government to reach an accommodation with the terrorists’.7 Contemptuously dismissing civilised warfare as ‘trash’, O’Donovan Rossa planned no-warning attacks on British government buildings, transport systems and even places of entertainment. By consciously targeting civilians, he intended creating a general panic that would destroy the British public’s faith in the authorities and catapult Ireland’s cause on to a worldwide stage.

O’Donovan Rossa’s operatives commenced their bombing offensive in January 1881 with an explosion at Salford army barracks in Lancashire that killed a young boy. Despite a shoestring budget that necessitated them using cheap gunpowder, they gradually fomented a reign of terror, making the civilian population fearful of ‘an invisible adversary who could strike at any moment unsuspected and unknown by those around him, hidden and protected by anonymity’.8 Many Clan members became uneasy at O’Donovan Rossa forcing the pace and grabbing all the headlines and glory, at their organisation being outdone by a ‘revolutionary showman’9 who was emerging as the first bogeyman of a new terrorist age. Most of O’Donovan Rossa’s operatives were Clan defectors and there was a fear of more members leaving to join him. Clarke – himself a natural Skirmisher – was probably torn between his own warlike instincts and his loyalties as a Clan official. But he regarded unity as an overriding principle, especially after the internal strife that had destroyed the Fenian Brotherhood and disabled the IRB. Furthermore, Tom’s political antennae must have detected that increasing rank-and-file discontent in the Clan would soon change either the organisation’s policy or its leadership and probably both. And since the Clan’s membership and financial resources were far superior to O’Donovan Rossa’s Skirmishers, any bombing campaign by it was bound to be far more destructive. Clarke would have wanted to be part of that.

Clan members’ dissatisfaction at a lack of action finally erupted in August 1881 during an annual conference (the ‘Dynamite Convention’) at Chicago. One observer, Henri Le Caron, recalled that:

Nothing was talked of but the utter lack of practical effort which had characterised the past two years. The whole question of active operations came up and was debated at great length. Many of the delegates present attacked both the Revolutionary Directorate and the Executive Body for having practically done nothing.10

Devoy was unable to hold the line and resigned his presidency, leaving delegates ‘determined that some outward and visible sign should be given England of its power of doing mischief’.11 His successor was Alexander Sullivan, an archetypal city boss whose political machine dominated Chicago. Ambitious and unscrupulous, Sullivan was a lawyer with a well-deserved reputation for his iron nerve, ruthlessness and a coldly ferocious temper. He always carried a pistol and had once been acquitted by a packed jury after killing a school principal for allegedly insulting his wife; later he shot and wounded a political rival. Clearly Sullivan was not someone for whom violence was a distasteful last resort.

Anxious to make up for lost time, Sullivan intended outdoing O’Donovan Rossa with a Clan bombing campaign in England that would use powerful dynamite instead of gunpowder. Irish Republicans regarded dynamite as the nineteenth century’s weapon of mass destruction and a radical alternative to their traditional but unsuccessful strategy of mass rebellion and open warfare. Vastly exaggerating its destructive power, they had dreams of airships bombing English cities and explosives teams crossing the Atlantic to incinerate London, inflicting on it the same devastation that Rome had once visited upon Carthage. Such visions had transfixed Clan delegates to the Chicago convention and one recalled that although ‘the word dynamite finds no single place in the official records of the assembly it was in the air and in the speeches from start to finish’.12 Sullivan told his confidante, Henri Le Caron, that America alone would control, fund and staff the bombing campaign in England, hermetically insulating it from the IRB in Ireland and Great Britain. Although employing Irish and British members with local knowledge might have been preferable, Sullivan distrusted an IRB Supreme Council that opposed bombing and feared it might sabotage his strategy. He also believed the Royal Irish Constabulary had penetrated the IRB and told Le Caron – almost certainly wrongly – that the Royal Irish Constabulary had forty agents in America trying to infiltrate the Clan.

Sullivan delegated the selection and training of Clan members for bombing missions in England to Thomas Gallagher, a 32-year-old doctor. Born in Glasgow to Irish parents from Donegal, Gallagher had emigrated early to America where he joined Clan na Gael and graduated from a New York medical school. With a lucrative practice in Brooklyn he became a dapper man about town, sporting a gold-tipped walking cane, but Gallagher’s strident hatred of England and his knowledge of chemicals took him into much darker territory. Le Caron recalled him going on and on about ‘making experiments in the manufacture of explosives and advocating their use. He was quite enthusiastic in their praise and so carried away by his subject that he expressed his willingness to undertake the carriage of dynamite to England and to superintend its use there’.13 After Sullivan granted his wish, Gallagher established a training school to instruct Clan recruits in the manufacture and use of dynamite.

John Kenny, the president of the Clan’s Napper Tandy Club who had sworn in Clarke and Kelly, recalled a meeting at which:

A secret call was issued for volunteers to do something more than talking for Ireland. The nature of the work was not stated but it was intimated. One of the first to volunteer for that job was young Clarke. It was no boyish adventure with him. He was a sensible and thoughtful young fellow who fully realised the risks to be undertaken. Tom Clarke came to me that night and quietly asked to have his name sent to the proper quarters for service in any capacity.14

Clarke certainly met Sullivan’s criteria about recruits being loyal and intelligent young bachelors with no close personal ties: Tom had no wife, children or even a girlfriend to worry about if things went wrong and he had also deliberately severed contact with his family in Ireland. A Tyrone accent would also enable him to melt into London’s large Irish population. After being vetted Tom was chosen. Billy Kelly had volunteered at the same time as Clarke but was turned down. At Gallagher’s training school in Brooklyn, Tom learned about handling and detonating dynamite, clearly impressing the doctor who brought him to a deserted part of Long Island where he gained experience by blasting rocks with nitroglycerine. After graduating with honours, he made it on to Gallagher’s bombing team. His time had finally come.

An audacious bombing campaign in England undoubtedly appealed to Tom’s dramatic imagination, offering him a starring role in a lethal form of street theatre that would soon usher in a new world of global terrorism. Not long before, Clarke had been teaching in a rural Ulster backwater, but now, along with other fanatical young men – ‘dynamite evangelists’ – he stood poised to travel vast distances and strike at the very heart of the British Empire. Secretive, single-minded and ruthless, with no moral qualms about killing civilians, Tom was well suited for such a dangerous venture. In his mind the rules of war apply did not apply to England and its people; they were liable to be attacked anywhere – in government offices and crowded shops or on the streets, buses, trains and underground system. Tom was not squeamish about causing deaths and casualties and it could have been him, not O’Donovan Rossa, who declared that ‘I believe in all things for the liberation of Ireland. If dynamite is necessary for the redemption of Ireland then dynamite is a blessed agent of the people of Ireland in their holy war. I do not know how dynamite could be put to better use than in blowing up the British Empire’.15 Drinking from the same well of rage and visceral hatred as O’Donovan Rossa, Tom would let nothing stand in his way, not even an IRB Supreme Council opposed to bombing. Nor was he bothered about operating in an English capital teeming with soldiers, policemen and the newly formed Special Branch of Scotland Yard. Dangers such as premature explosions, imprisonment and even execution concerned him not at all.

In October 1882, Sullivan sent Gallagher on a reconnaissance mission to England.16 Posing as an American tourist, he spent a couple of months gathering intelligence on security measures and potential targets like the House of Commons, Scotland Yard and government offices in Whitehall. Returning to America, Gallagher submitted to the Revolutionary Directorate a favourable report on the prospects for a bombing campaign in England. Impressed, Sullivan approved one commencing in early April 1883, appointed Gallagher as its leader and allocated him funds. Gallagher could not wait to get started and wearied Le Caron by talking about ‘nothing but dynamite, its production, its effectiveness and the great weapon it was soon to prove against the British government’.17 But it is surprising that in Sullivan’s small circle nobody queried Gallagher’s obvious vested interest: a bombing campaign’s most enthusiastic supporter had been chosen to assess its chances of success. Having done so much to get the bandwagon rolling in the first place, Gallagher would have had great difficulty halting it even had he wanted to.

The Clan’s bombing campaign was lamentably flawed from start to finish. Sullivan and the Revolutionary Directorate had seriously overestimated Gallagher’s ability, swayed perhaps by his professional standing and confident manner. In reality Gallagher was just as inexperienced a conspirator as the men he led. Tom’s fate now rested in the hands of an amateur who was about to give a master class in ineptitude. And in another way Gallagher was not quite what he seemed, because he was secretly working both sides of the street. While nominally a Clan member following Sullivan’s instructions, Gallagher had surreptitiously allied himself with O’Donovan Rossa, the politician he most admired, in a dual allegiance that made Gallagher effectively a Skirmisher, piggybacking a free ride on the Clan’s superior resources. Furthermore, despite Sullivan’s boasts about a blanket of absolute secrecy, a British intelligence agent had infiltrated his operation. Ironically this was none other than Henri Le Caron, the very person Sullivan had cautioned about the necessity of preventing enemy penetration. For fifteen years this ‘Prince of Spies’ had been reporting on the Clan’s activities and leaders. But despite warning the British government in general terms about what was coming, Le Caron could not provide Special Branch with the bombers’ identities, hiding places and intended targets. Initially at least, the authorities had to rely on catching a lucky break.

Gallagher organised his mission in two separate phases. First, he decided that tight security at ports made smuggling commercially manufactured dynamite into England too risky and planned instead to produce explosives in the country itself. Only when a stockpile was ready would he and the other team members cross the Atlantic to commence attacking strategic targets in London. But Gallagher had only assembled a small group and his operation was under-resourced from the start. In late January 1883 he sent just one person, Alfred George Whitehead, in advance to the English midlands city of Birmingham. In this unfamiliar location, Whitehead was expected by himself to rent and convert premises into a shop that he alone would run as a front for a bomb-making factory in which he would manufacture gelignite. And although secreting Whitehead far away from London certainly increased operational security, it meant that highly unstable nitroglycerine would have to be transported by train over a hundred miles south to the English capital.

After giving Whitehead a couple of months to set himself up in Birmingham, Gallagher and the others sailed separately to England during March 1883. The first conspirator out was John Curtin, an iron moulder who arrived in Liverpool after visiting his parents in Co. Cork. Alfred Lynch, a 22-year-old coach painter using the pseudonym ‘Norman’, followed on 13 March with orders to stay in London and await Gallagher’s further orders. Lacking a strong personality and completely untrained in explosives, Norman was probably selected because of his pliability, someone whom Gallagher could use as a glorified errand boy. Gallagher himself embarked on 14 March, travelling on the same ship – but in a different class – as his alcoholic brother Bernard and another passenger, William Ansburgh. Whether Bernard Gallagher and Ansburgh were actually connected to the plot is still unclear. Clarke was last out, leaving from Boston in the guise of Henry Hammond Wilson, supposedly an Englishman returning home. Sworn to secrecy, Tom confessed many years later that it had been one of the hardest things in his life not telling even his best friend Billy Kelly that he was going thousands of miles away on a mission.18 Now working in another Long Island hotel, Kelly first learned about Tom’s disappearance when a suitcase of his belongings arrived for safekeeping along with a note warning him to stonewall any inquiries from Tom’s family.19 On the voyage to England and for the second time in Clarke’s life, he nearly drowned when his ship hit an iceberg, but a passing vessel rescued the passengers and brought them to Newfoundland. Tom then completed his journey to Liverpool.

Whitehead, meanwhile, had been building up his cover in Birmingham. On 6 February 1883, he bought premises 2 miles south of the city centre that he eventually opened as a paint and wallpaper shop, an ideal front for purchasing the chemicals needed to make nitroglycerine. Whitehead dispersed the fumes through a back kitchen funnel connected to the chimney. To keep watch over his arsenal, Whitehead took lodgings in rented rooms next door to his shop. Unsurprisingly, he was soon unable to cope with serving customers while secretly manufacturing dynamite, so he hired a 13-year-old boy to work the counter. The youth proved remarkably incurious, even after an explosion at the rear of the shop that Whitehead dismissed as an accidental pistol discharge. If Whitehead had been further along in manufacturing explosives, he, the boy and many residents nearby would have perished. But employing a very young assistant and packing an inordinately large number of boxes into such small premises was always likely to create suspicions about Whitehead’s business. Near the end of March 1883, a supplier tipped off police who secretly entered the shop and discovered its true purpose. It was the intelligence breakthrough that Special Branch so desperately needed and Birmingham detectives immediately began covert surveillance of Whitehead’s customers and visitors. On 28 March they got lucky when Thomas Gallagher travelled from London to inspect Whitehead’s progress. Shortly after Gallagher’s arrival they were unexpectedly joined by Clarke who had just travelled from Liverpool – evidence of Gallagher’s inability to co-ordinate the conspirators’ movements and organise effective counter-surveillance. In quick order the police had identified three prime suspects.

The next day Gallagher and Clarke travelled together by train to London, where Tom took lodgings in a private house situated among an Irish community near Blackfriars Bridge. Inexperienced and inadequately trained, Tom then sent Whitehead an uncoded letter containing his new address; he also revealed his intention of returning to Birmingham to collect explosives that would be used to start bombing the capital. On 5 April 1883, Clarke helped Whitehead pour 80lbs of nitroglycerine into rubber fishing stockings and pack them into a case. He then took it by cab to Birmingham’s main railway station and caught the return train to London. A detective had tailed Clarke’s cab but lost it in the heavy traffic. Just after Tom had left, Norman turned up at Whitehead’s shop. Norman had been holed up at a Euston Square hotel in London until Gallagher dispatched him to Birmingham to bring nitroglycerine back to the capital. After collecting a wooden trunk packed with 200lbs of explosives, Norman went by taxi to Birmingham railway station, where he sent Gallagher a telegram arranging for them to meet at Euston Station in London. Norman then travelled south on the 6 p.m. train, but in the next compartment were Birmingham detectives who had sent a telegram warning Special Branch in Scotland Yard about Norman’s imminent arrival. At 9 p.m. Gallagher met Norman at Euston Station and they went by taxi towards a hotel in the Strand where Norman was to store the explosives. But Special Branch detectives shadowing the pair lost track of Gallagher when he slipped out of the cab just before it reached the hotel. After a few hours waiting in vain for him to reappear, they gave up, went inside and arrested Norman.

British authorities then began rounding up the remaining suspects. Early on 5 April 1883, Birmingham police raided Whitehead’s accommodation and arrested him. They also discovered Clarke’s uncoded letter to Whitehead containing his Blackfriars address which, incredibly, Whitehead had not destroyed. The Birmingham police next advised Scotland Yard detectives to discreetly watch Clarke’s lodgings. Just after lunchtime Tom returned there accompanied by Gallagher and Chief Inspector Littlechild of Special Branch arrested them both. By then police were searching Norman’s room in Euston Square where they discovered a telegram from Gallagher’s Charing Cross hotel. They then searched Gallagher’s room and found a letter from Curtin’s London address. Soon afterwards detectives apprehended Curtin. Like a circular firing squad, the conspirators had destroyed each other through messages they should neither have sent nor retained. William Ansburgh’s London address was also found in Gallagher’s hotel room, although the two men had apparently never met again after crossing the Atlantic. An inebriated Bernard Gallagher was detained in the family home town of Glasgow where he had been on a never-ending pub crawl since arriving from America.

It had been a close call for Special Branch. Although they arrested Gallagher’s entire team and seized 500lbs of nitroglycerine, things could have turned out very differently but for civilian alertness and the conspirators’ own folly. On separate occasions, detectives trailing Clarke and Thomas Gallagher had lost them and only luck facilitated their eventual capture – still in possession of enough explosives to inflict carnage on London. It must have galled Tom and Gallagher to have come so close to success only to fall into enemy hands at the last moment, and to be rounded up so quickly, Gallagher after only ten days in England and Clarke a day less. Literally overnight Tom’s situation had changed dramatically, from potentially holding the power of life and death to a state of utter helplessness. He and the other Irish prisoners were remanded to Millbank Prison, an immense yellow-brown fortress on the north bank of the Thames close to the Houses of Parliament and the Old Bailey, where they would soon stand trial for treason-felony. A mightily relieved public craved to know what these ‘monsters’ looked like, but at that time newspapers lacked any photographs to satisfy its curiosity. Even the Prince of Wales was intrigued and had his private secretary approach the governor about the possibility of Edward inspecting the prisoners ‘quite privately’.20 But ultimately the royal tour of Millbank never materialised.

However, police photographs of the bombers did exist, taken very shortly after their arrest, still in civilian clothes.21 Millbank’s governor presented them to the head of the prison service, Sir Edmund du Cane, jocularly apologising for the poor image of an agitated Whitehead, ‘taken by the instantaneous process whilst the gentleman was objecting and great was his vexation when he realised that we had secured his likeness!!’22 But Clarke’s photograph was very different. Not despairing or blankly uncomprehending, he was sitting in an armchair dressed like a middle-class businessman or academic. Captured and on remand, he knew that his life had just changed forever – and not in a good way – yet he remained composed and dignified, his eyes locked unflinchingly on the camera. Silently, Tom seemed to be marshalling his resources for battles soon to be fought.

Although presumed legally innocent, Tom was treated as a convict from the time of his arrest. Apart from a daily hour of exercise and attendance at chapel, he was held in solitary confinement, a regime that Michael Davitt, a former Fenian prisoner in Millbank, regarded as ‘a very terrible ordeal’.23 Davitt especially remembered hearing:

The voice of Big Ben telling the listening inmates of the penitentiary that another fifteen minutes have gone by. What horrible punishment has not that clock added to many an unfortunate wretch’s fate by counting for him the minutes during which stone walls and iron bars will a prison make.24

And there were other reminders of a noisy, joyful world just beyond reach such as the strains of a band in St James’s Park and railway engine whistles ‘with the suggestiveness of a journey home’.25 Things hadn’t changed much by Clarke’s time. Although he conceded that the Irish prisoners ‘were not treated with exceptional severity’,26 the surveillance was close and continuous. They were not allowed to converse and Tom was caught out twice when he tried. Written messages were also forbidden, but despite having no pens or pencils they succeeded in communicating with each other: ‘A fellow has no business in prison unless he is resourceful and observant’.27 But the mental desolation was a different matter:

Looking back now to my imprisonment in Millbank I get a picture of a dreary time of solitary confinement in the cold white-washed cell with a short daily exercise varying the monotony. Day after day all alike, no change, maddening silence, sitting there in that cell, hopeless, friendless and alone with nothing in this world to look forward to but that one note occasionally coming to me from one or another of my poor comrades, Gallagher, Whitehead and Curtin who were in the same plight as myself.28

The authorities spent almost three months strengthening their case against Gallagher’s team. They had Whitehead on manufacturing and possession, Clarke and Norman on possession, and could prove Thomas Gallagher’s association with all three men. The police had also seized incriminating documents. But evidence against the rest was weaker and largely circumstantial; charging them all initially with treason-felony was problematic. There were no captured maps or notes detailing targets, vital in persuading a jury that the defendants had really intended using the dynamite in a deadly fashion. So the prosecution caught a lucky break when a chastened Norman, his mind concentrated wonderfully by five days in prison and the prospect of thousands more, contacted Scotland Yard and offered to become a prosecution witness. And what a story he had to tell. In his version he, a young man, trusting and naive, opposed to violence and with no real interest in Irish politics, had been dropped right in it by a manipulative Thomas Gallagher. Norman claimed that the doctor had accompanied him around London pointing out bombing targets like the Houses of Parliament (‘This will make a great crash when it comes down’) and Scotland Yard (‘That will come down too’).29 The prosecution knew that if Norman could sell himself convincingly to the jury as a victim of Gallagher’s manipulation, it would clinch their case. And to secure his testimony, it gave Norman a sweet deal: no jail time, a new identity in a foreign country and possibly – republicans believed undoubtedly – piles of money for a fresh start in life.

The trial of Clarke and the others began on Tuesday 22 June 1883 at London’s Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey, and because of the great demand for seats at the ‘Dynamite Conspiracy’ trial, admission was by ticket only.30 The Lord Mayor welcomed its three presiding judges, Lord Chief Justice Coleridge, Master of the Rolls, Lord Justice Brett and Mr Justice Grove. For their protection, barricades had been erected at various court entrances, while policemen flooded the nearby streets to deter a rescue attempt, an explosion or hostile crowds: ‘The prisoners were brought to and taken away from court under a strong guard of mounted police, the appearance of the van and its armed escort causing much excitement as it passed through the streets’.31 The six accused men knew nothing about Norman’s pre-trial negotiations with the prosecution and on the first day a journalist reported that ‘when Norman appeared, instead of going into the dock, he proceeded with chief inspector Littlechild to the witness box. I shall never forget the look of consternation on the faces of the prisoners as he was being sworn by the court’.32 All the defendants pleaded ‘Not Guilty’. Five were legally represented – two by QCs – but Clarke acted as his own defence counsel. Whether handling explosives or appearing before the three most senior judges in the land, Tom demonstrated his great self-control, confidence and a willingness to stand alone. But he was also determined to keep the conspiracy’s secrets to himself and knowing that the less he said in court the better, Clarke declined to testify on his own behalf. Most of what he did say in court was a lie, including his continued insistence that he really was 22-year-old Henry Wilson and a punning claim that he worked as a clerk. Resisting grandstanding, Tom limited himself to interventions designed to create reasonable doubt. Trying to undermine the credibility of eyewitness identification, he successfully extracted admissions from his Birmingham cab driver and Whitehead’s young shop assistant that they did not conclusively recognise him. But a detective insisted Clarke was the man he had tried following to Birmingham’s central railway station. And while Norman admitted never having met Clarke and could not connect him directly to the plot, he had already sunk Gallagher, with whom Tom had been arrested – and at Tom’s accommodation where a significant amount of explosives was present. If jury members connected the dots, then Clarke was in serious trouble.

Since no defendant testified, the trial lasted only four days. Clarke declined to make any closing arguments and after the Lord Chief Justice’s summing up, the jury needed just an hour and a quarter to convict him, Thomas Gallagher, Whitehead and Curtin, though it acquitted Ansburgh and Bernard Gallagher. Thomas Gallagher buckled on hearing the verdict, swearing on his mother’s grave that he was the victim of a tragic miscarriage of justice and had never even met O’Donovan Rossa, the plot’s supposed mastermind. Gallagher’s denials failed to sway the Lord Chief Justice who sentenced all four convicted men to penal servitude for life. Spectators cheered, as did the crowds gathered outside when they heard the news. Clarke shouted at the judge, ‘Good-bye we shall meet in Heaven’.33 He remembered being ‘hustled into the prison van, surrounded by a troop of mounted police and driven at a furious pace through the howling mob that thronged the streets from the Courthouse to Millbank Prison. London was panic-stricken at the time’.34

NOTES

1 The question of Tom Clarke’s place and date and place of birth has been complicated by anonymous and erroneous notes deposited in his private papers at the National Library of Ireland. Accepting these at face value, Gerard MacAtasney in his book Tom Clarke: Life, Liberty, Revolution stated that Clarke was born in 1858 at Hurst Castle on the Hampshire coast. Later in the nineteenth century, Hurst Castle was re-fortified with a military garrison but only after a government report of 1859 by which time the Clarke family was in South Africa. Writing almost eighty years before MacAtasney, Louis Le Roux in his book Tom Clarke and the Irish Freedom Movement had apparently realised this error and assumed that the anonymous writer of the notes must have meant Hurst Park Barracks on the Isle of Wight where Clarke’s father’s regiment was then stationed. Kathleen Clarke also reinforced her claims about Tom’s age by asserting that he was 26 years old when he went to prison in June 1883 and 41 years old when he was released in September 1883 (‘A Character Sketch of Tom Clarke’, NLI MS 49,355/12). I am grateful to the General Register Office for Births, Marriages and Deaths, Southport, England for the information concerning births in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight in 1857 and 1858. Both MacAtasney and Le Roux also accepted the incorrect dating by the writer of the anonymous notes of 31 March 1857 as the occasion of Clarke’s parents’ marriage. I am grateful to the present rector of Shanrahan Church, Rev. Barbara Fryday, for providing me with a copy of the marriage certificate. There is also a marriage certificate with the same details at the General Register Office, Dublin.

2 In his life of Clarke, Louis Le Roux asserted that Daly had sworn in Clarke and Kelly in 1882 – a time when both men were living in America. However in a letter to the Irish Press on 4 March 1937, he corrected himself by writing that he had a statement from Kelly saying that he, Clarke and a few other friends had been sworn into the IRB in 1878. For Clarke and Kelly’s friendship, see William (Billy) Kelly, BMH WS 226 and also Kelly’s manuscript notes on the early life of Tom Clarke in Ireland and America, NLI MS 44,684/1.

3 John Devoy, Recollections of an Irish Rebel, p. 254.

4Belfast Telegraph, 18 August 1880.

5 For the New York Irish, see Jay P. Dolan, The Irish Americans: A History. Also Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy Meagher, The New York Irish.

6 For the Clan split and the onset of the dynamite campaign, see Terry Golway, Irish Rebel: John Devoy and America’s Fight for Ireland’s Freedom, pp. 139–45.

7 Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1848–1922, p. 328.

8 Shane Kenna, ‘The Politics of the Bomb’ in Fearghal McGarry, The Black Hand of Republicanism: Fenianism in Modern Ireland.

9 Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1848–1922, p. 336.

10 Henri Le Caron, Twenty-Five Years in the Secret Service, pp. 187–8.

11 Ibid., p. 187.

12 Ibid., p. 188.

13 Ibid., p. 192.

14 Lecture on Clarke by John Kenny, Gaelic American, 12 January 1924.

15 O’Donovan Rossa quoted in Jonathan Gannt, Irish Terrorism in the Atlantic Community 1865–1922, pp. 132–3.

16 For the dynamite campaign in England, see Shane Kenna, War in the Shadows: Irish American Bombers in Victorian Britain. See also K.R.M. Short, The Dynamite War: Irish American Bombers in Victorian Britain.

17 Henri Le Caron, Twenty-Five Years in the Secret Service, p. 192. See also pp. 200–1.

18 Kathleen Clarke in a letter to the Donegal Democrat, 9 October 1964. There is a copy in the Seán O’Mahony Papers, NLI MS 44,101/4.

19 Billy Kelly, William (Billy) Kelly, BMH WS 226 and NLI MS 44,684/1.

20 Letter from the Governor of Milbank to Sir Edmund Du Cane, 23 April 1883. Papers of Sir Edmund F. Du Cane, MSS. Eng. Misc. d. 956-8. 961 Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

21 The original photographs are deposited in the Du Cane Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

22 Letter from the Governor of Milbank Prison to Sir Edmund du Cane, 23 April 1883, Du Cane Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

23 Michael Davitt, Leaves from a Prison Diary, p. 171.

24 Ibid., p. 172.

25 Ibid.

26 Clarke in a lecture he gave in 1899 to Dublin’s ’98 Club, a year after his release from prison. Clarke’s copy, sadly incomplete, is in the Clarke Papers, NLI MS 49,354/6.

27 Clarke, Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life, p. 12.

28 Ibid., pp. 12–13.

29 K.R.M. Short, The Dynamite War, p. 132.

30The Times, 12 June 1883. This newspaper carried extensive reports on the trial on 12, 13, 14 and 15 June 1883.

31The Times, 12 June 1883.

32Reynolds Weekly Newspaper, 22 April 1883. Cited in Shane Kenna, War in the Shadows, p. 143.

33The Times, 15 June 1883.

34 Tom Clarke, Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life, p. 11.

2

‘An Earthly Hell’: Prison 1883–1898

After returning to Millbank, Clarke was immediately initiated into the English convict system. First fitted out in a khaki uniform, he then had his hair cropped and became literally just a number as prisoner J464. Finally a senior officer read out to him the rules and regulations that he was to obey absolutely:

Nothing in them startled me like the one that stated, ‘Strict silence must at all times be observed; under no circumstances must one prisoner speak to another’. When I thought of what that meant in conjunction with another paragraph, ‘No hope of release for life prisoners till they have completed twenty years, and then each case will be decided on its own merits’, and remembered with what relentless savagery the English government has always dealt with the Irishmen it gets into its clutches, the future appeared as black and appalling as imagination could picture it.

Another Irish prisoner declared that ‘the announcement never failed to stagger even the most hardened and reckless criminal’.1

Convicts normally spent the first nine months of their sentence in solitary confinement, but since Millbank usually held only remand prisoners, Clarke, Gallagher, Whitehead and Curtin were soon transferred out. Awakened suddenly on 25 August 1883 and ordered to dress quickly, they were handcuffed in a chain gang, surrounded by a posse of armed officers and escorted to a nearby railway station. Their destination was Chatham Prison, about 30 miles east on the southern shore of the Medway estuary and situated just outside the town itself.2 At this time Chatham exuded British military and industrial power, with forts and army barracks protecting its great naval dockyard while ships plied one of Europe’s busiest waterways, constantly replenishing the wharves, workshops and warehouses. For decades inmates from England’s largest public works prison had been extending the dockyard, building new basins and dry docks; now Clarke too was destined to toil here for many years, helping to raise more great monuments for his captors. Alighting from their train at Chatham, Clarke’s party was put in a horse-drawn Black Maria and driven to the prison’s reception hall, where an officer recorded Tom’s name, religion, occupation, place and date of birth. Clarke still insisted that he was Henry Hammond Wilson, born in Great Yarmouth in Norfolk and three and a half years younger than his real age of 26.3 Warders measured Clarke’s height and weight, gave him a medical examination, took his photograph and recorded details of his complexion, hair and eye colour. After bathing he was escorted along corridors and walkways to a cell.

Stretching almost half a mile, Chatham Prison held 1,700 convicts and housed another 2,000 people. The governor, Captain Vernon Harris, and his two deputies had their own living quarters, while accommodation was provided for senior officers, over a hundred warders and their families, four chaplains, two doctors, nurses, scripture readers, civil guards and schoolmasters. The grounds contained a chapel and infirmary, an administrative block with offices for Harris and his deputies, a reception office and a search room for visitors. There was also a library, a warders’ mess room and a staff reading room as well as a cookhouse and a bathhouse. An edifice in the middle contained the convict cells. Chatham Prison resembled a small factory town with workshops that employed inmates as tailors, shoemakers, printers, blacksmiths, carpenters, wheelwrights and fitters. Other prisoners laboured in an iron foundry, cultivated gardens and vegetable plots or dressed stone brought from quarries at Portland in Dorset.

As a high security prison, Chatham had a permanent military presence, a guardroom stocked with weapons, armed sentries at the main gate, an army barracks nearby and a police unit that investigated criminal offences committed inside the gaol. A former army officer, Harris ran his prison with ‘clock-like precision’.4 He had personally recruited many former soldiers and sailors as warders and they shared his belief that ‘discipline was a first duty and to exact it from others a second of at least equal importance’.5 Their attitude chimed with Gladstone’s Home Secretary, Sir Edward Harcourt, who rejected the dynamitards’ claim to be prisoners of war and implacably denied them political status. Harcourt encouraged Harris to treat Clarke and his comrades as felons. So did the Director of Prisons, Sir Edmund du Cane, an austere and intellectually brilliant civil servant who for decades had seen off successive Home Secretaries while outlasting every prison reformer. Enjoying such high-level protection, Harris’s hard-line approach meant that ‘everyone must conform and either fall out or be crushed’.6

The Governor’s stringent controls were partly intended to prevent the Irish convicts hatching escape plots or enlisting outsiders to spring them from prison. There were precedents. In 1867 Fenians had freed two republican leaders from a horse-drawn police van in Manchester and three months later they also exploded a bomb outside Clerkenwell Prison in London, killing a dozen civilian bystanders. Harris’s anxieties about security swelled as Special Branch hunted down the remaining dynamitards in London, Liverpool and Glasgow and imprisoned them at Chatham, twenty-one in all. To prevent any breakouts on his watch, he kept the prison permanently on high alert, ordering that every vehicle entering and leaving be searched, right down to the baker’s and butcher’s vans. Designating the Irish convicts as Special Men, he concentrated them in a separate penal block that was located a considerable distance from the ordinary prisoners. Hidden away from an unsympathetic English public and abandoned even by many Irish nationalists, Clarke did not anticipate getting his freedom for a very long time – if ever. Such oppressive isolation left the Special Men feeling like the Forgotten; one wrote that ‘we, the Irish convicts, were virtually in a living tomb, cut off from everything and hearing no human sounds but hard words and harsh orders from the warders’.7

Chatham’s regime enforced discipline among prisoners right from the start by driving out rebelliousness and making them malleable. Except for short exercise periods and attendance at chapel, Clarke was initially confined to his cell all day, spending many dreary hours picking oakum. This involved separating lengths of old ship’s rope into coils by sliding them back and forth on his knee and removing tar and salt from the strands which would later be used to caulk the seams of wooden ships. Such repetitive and intellectually deadening work was ‘a dreadful and cruel occupation. It annoys the fingers and was monotonous to madness’.8 When Clarke finally entered the main prison population in early 1884, vigilant warders mounted close surveillance upon him virtually every waking minute and frequently throughout the night as well. They also searched him and his cell regularly for weapons and contraband. Ordinary rub-downs occurred routinely at least four times a day, but it was the prison officers’ twice monthly ‘disgusting’ body examinations, conducted with ‘the most repugnant minuteness’, that left Clarke feeling utterly violated. After stripping him naked on a bench, they probed every orifice with a lamp and he never forget their mocking running commentary or ‘the indecent and hurtful way some of the officers mauled me’.9 However, Tom hated even more the systematic sleep deprivation inflicted only on the Special Men; Clarke’s nightmares occurred during his waking hours. After every working day he would return wearily to his cell and throw himself down on the floor longing only for oblivion, but even when a bell rang and he retired to bed, it was difficult to nod off. And sleep, when it finally came, was constantly interrupted by a loud noise that resembled cannon fire, made by inspecting officers banging cell doors behind them. Once every hour a warder peered through a ‘Judas hole’ in cell doors: any prisoner who pulled a blanket over his head received a bread-and-water punishment and if he turned away the warder would shine a flashlight on a wall before slamming the peephole shut:

This went on night after night, week after week, month after month for years. Think of the effects of this upon a man’s system and no one will wonder that so many were driven insane by such tactics. The horror of those nights and days will never leave my memory. One by one I saw my fellow prisoners break down and go mad under the terrible strain.10

Harris’s most effective weapon in preventing the dynamitards from conspiring was a rule of perpetual silence that banned prisoners from conversing. Clarke even had to raise a hand first before being allowed to address a warder. Deputy Governor Griffiths conceded that:

A very vicious system for reports and punishments was in force at Chatham. All intercommunication was forbidden and the rule was strictly enforced by a stringent and meticulous discipline. It was easy to go wrong, very difficult to do right. Misconduct was scrupulously interpreted, the shadow of a ‘report’ would hang heavily over the whole body of convicts and might result in punishment for very trifling offences.11

Harris’s warders punished inmates for moving their lips, turning a head, keeping an untidy cell, hesitating to obey an order and not closing up in the ranks. To Clarke this was a cruel system of ‘perpetual and persistent harassing which gave the officers in charge of us a free hand to persecute us just as they pleased. It was made part of their duty to worry and harass us all the time. Harassing morning noon and night and on through the night’. 12 But Chatham’s warders saw it very differently. Believing Clarke and his comrades capable of mass murder, these ex-servicemen felt that they were in a sense still at war against a cunning and dangerous enemy and so they never let their guard down when around them, brooking neither argument nor delay. Furthermore, even a hint of them fraternising with prisoners risked official censure and accusations of trafficking contraband. Griffiths acknowledged that ‘almost invariably they were brusque and abrupt in manner, seemingly unsympathetic and little given to weakness as they would have deemed it, to gentle and conciliatory treatment of their charges’.13 Clarke often felt like a verbal punchbag when warders bellowed orders at him like a parade ground sergeant-major ‘with as much fuss and noise as if I were a whole regiment of soldiers’.14 Another Irish prisoner compared his incarceration to being ‘enveloped by a shroud’ and that ‘the nagging, the ordering about, the mental kicking and hammering crushed him to a pulp’.15 Clarke hated almost every officer, but apart from Governor Harris he most despised ‘Bully’ Parker whom he once witnessed hooting with laughter while punching and kicking a simple-minded prisoner unconscious. Only two of the staff at Chatham ever showed him any kindness – an Irish infirmary nurse who threw bread into his cell and whispered news items, and a Cockney who warned him to avoid a prison informer.16