7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grosvenor House Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

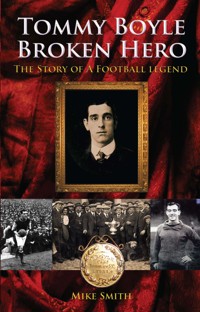

One of the most gifted centre-halves of his day, Burnley captain Tommy Boyle won all of English footballs major honours; the FA Cup, League Championship and he represented England at international level. But once his playing days were over and after run-ins with the police and local authorities, the former international footballer was sent to Whittingham Mental Hospital, a former lunatic asylum.Broken Hero traces Boyle's career from his early days working as a miner in the militant South Yorkshire coalfield, to the proud day he became the first captain to be presented with the FA Cup by His Majesty, King George V. The story covers Boyle's experiences during the First World War where he served in the Royal Field Artillery and was badly wounded. The doctors gave him little chance of ever playing again, but he proved them all wrong and made a remarkable comeback to crown his career by leading Burnley to the Football League title in 1921. Tommy Boyle - Broken Hero tells the story of a great character and explores the circumstances that led to one of footballs first celebrity players being locked away in a mental hospital for the rest of his life unable to tell his story. Until now.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 570

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

www.grosvenorhousepublishing.co.uk

Introduction

In September 1911, Thomas William Boyle walked through the doors of Burnley Football Club and a legend was born. Boyle was one of the most outstanding players of his generation, “one of the best centre-halves who ever stepped onto a football field… a gem amongst jewels,” was one football manager’s assessment of him. He represented England at international level and in 1914 became the first captain to be presented with the FA Cup by the reigning monarch, His Majesty, King George V. The Yorkshireman won all of football’s major honours, but once his playing days were over, something inside Tommy Boyle broke.

On leaving school at twelve, the young Tommy Boyle became a miner and his first sporting interest was in athletics where he competed as a sprinter, but it was football where he made his mark. Despite his stature at five-feet seven, his ability as an attacking right-half was spotted by the Barnsley manager Arthur Fairclough, who signed him to professional terms in 1906. Boyle went on to lead Barnsley to their first Cup final in 1910 and was later sold to Burnley. It was at Turf Moor where he made his biggest contribution to the game. Boyle led The Clarets to promotion to Division One, he represented England at full international level and won the FA Cup. When the First World War came he became Bombardier Boyle serving in the Royal Artillery on the Western Front. It was there he was badly wounded and for a while it looked like his playing career was finished. But being the gritty character he was, Tommy Boyle defied the consultants and fought his way back to play again. He crowned his comeback by winning the League championship in style, leading a Burnley side that stayed undefeated for thirty League matches, a record the club held until the Arsenal side of Dennis Bergkamp and Thierry Henry surpassed it in 2004.

There was no mistaking Boyle on the football field. With his jersey tucked in and his shorts pulled up nearly under his armpits, he would make the most noise, barking his instructions to his teammates. “A real captain if ever there was one,” said Charles Buchan about Boyle in 1932. He dominated games with sheer enthusiasm, determination and thrived on conflict. Yet despite all of his successes in the game and the enjoyment he brought to thousands, when his playing days were over Tommy Boyle struggled to come to terms with a life without football.

Broken Hero turns the clock back to the beginning of the twentieth century, revealing the events and people who played the game with Boyle at the time. By the early 1900s, football had changed. With the introduction of the Football League and win bonuses equal to a working man’s weekly wage, the former gentleman’s game was consigned to history. There was nothing gentlemanly in some of the brutal challenges meted out on Saturday afternoons in games that might also feature a punch-up or the continuation of an ongoing vendetta between players. And more often than not, in the thick of it all was Tommy Boyle, who gave as good as he got, all five foot seven of him.

September 2011 sees the 100th anniversary of Tommy Boyle’s arrival at Burnley Football Club. Broken Hero covers Boyle’s formative years; his background, what influenced him and the period of the First World War which devastated the team he played in. Finally the story looks at how after such an illustrious career, Tommy Boyle ended up with nothing, spending the last years of his life in a mental hospital. Drawing on material not previously published, Tommy Boyle - Broken Hero tells the remarkable story of a real football hero who in his prime had character, presence and generosity in abundance, but who in later life became a dangerous man, to himself and others.

Mike Smith

Summer 2011

Acknowledgements

A number of people deserve thanks for helping me put together the pieces of the Tommy Boyle jigsaw. Thanks go to David Wood, Arthur Bower and Grenville Firth of Barnsley Football Club who provided information about Tommy’s time there; David Coefield at St. Helen’s Church in Hoyland and Geraint Parry and Peter Jones who provided me with details of Tommy’s season at Wrexham FC. I’d like to thank Rob Cavallini, Ulrich Matheja, Jan Buschbom and Olaf Sievers for information on Tommy’s year working in Germany.

In Burnley, thanks go to local historians Roger Frost, Andrew Gill and Mike Townend at Towneley Hall and to Ken Ashton who manages the ‘Asylum’ website. Thanks to Roger and Sue Haydock for information from the Lancashire Football Association and to Paul Evans at Firepower, The Royal Artillery Museum in Woolwich. Thanks go to Tony Scholes, editor of ClaretsMad, the online website dedicated to Burnley supporters across the globe and to Charlie Wilson who helped me knock the story into shape. Thanks also to Derek Crossland for his advice and to Phil Drinkwater who helped me find the first piece of the Tommy Boyle jigsaw. Many thanks go to Ray Simpson at Burnley Football Club and to the living descendents of the Boyle family who live all over the world: Eileen Varey, John Jarvis, Maureen Sykes, Kevan Boyle and Sonia St. John, for their photographs and stories of ‘Uncle Tommy’.

Nearly finished, but they do deserve a special thanks: Burnley Central Library staff put up with me for nearly three years and provided an endless supply of books and documents from libraries all over the country. Thank you for the fantastic service you provide. If I have missed anyone, my sincerest apologies and I really do thank you for your help and support.

Finally, a special thanks go to my family for putting up with what became ‘an obsession’ and to apologise for all the lost weekends spent in archives, museums and libraries all over the UK living and breathing old football ‘stuff’.

About the Author

Mike Smith was born and brought up in Whittlefield in Burnley and one of his earliest recollections was as a five-year-old seeing the Burnley team touring the town in an open-top coach having won the 1960 League Championship. He has supported Burnley Football Club ever since and still lives in the area. Mike has a passion for sport history and has enjoyed an extensive career working in the engineering industry, teaching in further and higher education and he currently works at The University of Manchester and teaches for the Open University. Broken Hero is his first published work.

Disclaimer

The events that took place throughout this story were real. The people named in the story were real and the historical dates, events and facts found from official documents and source material provided in the story are all true. However, in drawing the facts together from over a century ago, the book cannot claim to be a totally accurate biographical account. Some elements of the latter part of the story can only be said to be what the author believes to have happened to the central character based on anecdotal evidence. As such the book makes no claim to be complete in every sense and aims to both inform and entertain.

For Julia, Clare, Dorothy and Norman.

List of Figures

Fig 1:Primrose Bank Infirmary, Burnley

Fig 2:Platts Common 1893

Fig 3:Platts Common street scene 1905

Fig 4:Hoyland Silkstone Colliery, Platts Common

Fig 5:Barnsley FC Crest

Fig 6:Barnsley FC team 1906-07

Fig 7:Barnsley FA Cup Team 1907

Fig 8:The Crystal Palace, Sydenham

Fig 9:Barnsley v Queens Park Rangers FA Cup Quarter Final 1910

Fig 10:Tommy tosses up at the 1910 Semi-final vs Everton at Old Trafford

Fig 11:Barnsley score in the FA Cup Semi-final

Fig 12:The Barnsley team fly to the Cup final

Fig 13:Barnsley 1910 Cup Final Team

Fig 14:1910 FA Cup Final programme featuring Tommy Boyle and Colin Veitch.

Fig 15:Tommy shakes hands with Colin Veitch at the kick-off.

Fig 16:Barnsley in Budapest on their summer European tour 1910

Fig 17:The Dubonnet Cup Competition in Paris 1910

Fig 18:The Mitre Burnley, 1911

Fig 19:Philip and Lady Ottoline Morrell portraits by Henry Lamb 1911

Fig 20:The Burnley team 1911

Fig 21:A selection of Tommy Boyle cigarette cards

Fig 22:Tommy scores against Blackburn Rovers at Ewood Park 1913

Fig 23:George Halley, Tommy Boyle and Billy Watson cigarette cards

Fig 24:Tommy and George Utley toss up in the semi-final at Old Trafford 1914

Fig 25:Burnley outside their training headquarters, Lytham, Lancashire

Fig 26:Burnley train on Lytham seafront

Fig 27:Ottoline Morrell with Burnley supporters outside the House of Commons

Fig 28:The Liverpool team

Fig 29:The Burnley team

Fig 30:The Cup Final Programmes

Fig 31:The Cup final gets underway

Fig 32:Bert Freeman scores the winning goal for Burnley

Fig 33:Tommy is presented with the FA Cup by His Majesty - King George V

Fig 34:Tommy with the FA Cup outside the Thorn Hotel, Burnley

Fig 35:Tommy is presented with a giant laurel wreath in Berlin

Fig 36:The Austrian sports journal, ‘Presse Sportblatt’ announce Burnley’s arrival

Fig 37:The Grand International – war as sport

Fig 38:‘The Gunners’ - The Lancashire Royal Field Artillery football team

Fig 39:Bombardier Boyle and Annie Varley at their wedding 1st March 1917

Fig 40:Fritz is kicked into touch

Fig 41:Tommy’s WW1 Medal Card

Fig 42:Tommy getting a massage from Charlie Bates at the start of the 1919-20 season

Fig 43:The Burnley team at the start of the 1920-21 season

Fig 44:Tommy Boyle caricature

Fig 45:Billy Nesbitt, Bob Kelly, Jo Anderson and Benny Cross

Fig 46:Tommy with the FA Cup and League Championship match balls

Fig 47:Tommy receives the League Championship trophy

Fig 48:The Burnley team with League Championship Trophy 1921

Fig 49:The Pedestrian Inn, Grimshaw Street, Burnley

Fig 50:Tommy as trainer/coach at Burnley in 1923 with the players

Fig 51:Central Berlin 1924

Fig 52:Whittingham Mental Hospital, Lancashire

Fig 53:Tommy’s 1921 Charity Shield Medal and Three International Caps

Fig 54:The Boyle family grave in St. Helens Churchyard, Hoyland

Fig 55:Coach Boyle in characteristic pose 1923

Picture Credits

Fig 2: Copied under agreement from The Ordnance Survey.

Fig 15: Courtesy of Paul Joannau - Newcastle United FC Historian.

Fig 16-17: Courtesy of David Wood, Barnsley FC Historian

Fig 31: Courtesy of Eric Hebden.

Fig 49: Copied with permission from Burnley Central Library.

Fig 53: Copied with permission of the Boyle family

Contents

Part One: The Boy from Platts Common

Chapter 1: Primrose Bank Infirmary 1932

Chapter 2: Roots

Chapter 3: The Boy from Platts Common

Chapter 4: Barnsley

Chapter 5: A Grand Day Out

Chapter 6: Burnley

Chapter 7: The Cup

Chapter 8: The Bloody War

Part Two: Broken Hero

Chapter 9: Boyle’s Brigade

Chapter 10: The Comeback

Chapter 11: One Last Chance

Chapter 12: Farewell Burnley

Chapter 13: Back in Business

Chapter 14: Together Again

Chapter 15: Whittingham

Chapter 16: Epilogue

Appendix

Bibliography

Thomas William Boyle: Honours

Comparing the performances of Burnley’s two League Championship winning sides

Part One:

The Boy from Platts Common

Chapter 1: Primrose Bank Infirmary 1932

O the thousand images I see

And struggle with and cannot kill…

Millions may have been haunted by these spirits

As I am haunted.

– Richard Adlington

The black Humber Pullman with its four occupants slowed to a halt on the gravel driveway outside the rear entrance of the Infirmary. The driver left the engine running and the wipers going as heavy morning rain continued to pour down from black-grey skies. It was also blowing a gale outside where, in the rain, stood two men wearing white hospital-issue jackets with matching trousers. Both held on to an umbrella in an attempt to keep dry. They were waiting for him.

In the back of Humber sat a man flanked by two police officers. “Where’s the rest of the welcoming committee? Where’s the papers and the bloody mayor?” asked the man. The two officers sitting on either side of him glanced at each other but made no reply. There would be no welcoming committee today, no press and no mayoral welcome. No fuss, that’s what The Chief had instructed.

The rear doors of the Humber opened and the two officers and their prisoner, handcuffed to one of them, stepped out. At six foot, the two officers towered over the man in their custody by a good six inches. The prisoner looked pale and undernourished. He wore a long shabby gabardine overcoat with no belt, a shirt buttoned at the neck with no tie and trousers that had not seen creases for some months. Unshaven and reeking of last night’s booze, he sported a week-old black eye and looked like he’d slept in his clothes for the last month.

Through bloodshot eyes the man looked upwards through the rain and it suddenly clicked where he was. Bloody hell…back ere’ He grinned to himself. He knew where this place was; he’d been here before, lots of times. They’d fix him up good style so he could play again, no problem. But right now he could do with something to cure the pounding in his head that felt like it was about to split open.

The two officers and their prisoner went inside and were followed by the two white coats. One of them closed and locked the heavy outer door, then locked the inner iron gate behind it with a loud, clang. The door secured the five men shook off the rain and climbed the stone staircase to the first floor, their footsteps echoing in the damp hallway. The white coats followed the three visitors up the stairs and whispered to each other. They couldn’t believe who it was.

Figure 1. Primrose Bank Infirmary, Burnley

Tommy Boyle arrived on the male mental wing of Primrose Bank Infirmary in Burnley on Wednesday 24 February 1932 for what was officially deemed ‘a period of observation’. It was said he had been ‘unwell’ for a number of weeks and had arrived at the Infirmary in a police car following a night in the Burnley police station cells. No charges had been made about the incident that took place on the Tuesday evening and no record was kept of it. Tommy Boyle was a well-known character in the town and had been for well over twenty years. He knew the police and the Chief Inspector well enough from his football days and his previous charity work in the town. He knew them also for another reason, the charges they had made against him nine years before. He’d not forgotten that.

In recent weeks he’d been in trouble again. He had allegedly been barred entry from a number of town centre pubs for causing trouble, so the previous evening when the landlord of one pub refused him a drink, he had gone berserk and swiped all the glasses off the bar. That was one story. The police were called and they carted him off to the station. It wasn’t the first time and when the Chief Inspector found out it was the last straw.

On the day of his admittance to Primrose Bank, Tommy Boyle was forty-six years old. The booze had added another ten years to his appearance. Only a decade before, he’d had it all: worshiped by his adoring fans, a local celebrity with a glittering career behind him and idolised in the press. Tommy Boyle, leader of the legendary ‘Boyle’s Brigade’, England international, FA Cup winner and League champion. He’d even met the King. With money in his pocket, his own pub in the centre of town, he was the main man, Mr Burnley and drinks all round. Ten years down the road, he was Tommy Boyle of no fixed abode, on the dole and sleeping rough in the local doss-house. The good times were long gone; in fact, everything had gone: the pub, the house, the money and Annie had left him. If the last eighteen months had seen a decline in Tommy’s personal and financial affairs, more worrying was his disturbed mental state and his temper, which after the previous night’s performance in the pub, had been brought to the full attention of the Burnley authorities.

Primrose Bank Infirmary was located on a ten-acre site on the outskirts of town. Opened in 1876 as the Burnley Union Workhouse, part of it had been converted to an infirmary twenty years later. As a workhouse, it had employed a strict regime in which inmates faced harsh working conditions in repayment for food and lodgings, and even after its conversion, the place still wasn’t exactly The Savoy. The Infirmary was large enough to accommodate male and female patients, the chronic sick and elderly patients and sick children. It also had two secure mental wings that could accommodate up to seventy-four male and the same number of female patients. The mental wings were located on the ground floor, which also contained the guardians’ boardroom, master’s offices and a storeroom for the inmates’ clothes. The master’s and matron’s bedrooms were located on the first floor at the rear along with the resident medical officers’ office. Male patients were accommodated in the west wing and females in the east. To enable segregation of the sexes the corridors were barred with locked iron gates. The facilities for mental patients at Primrose Bank supported mainly short-stay patients until more permanent accommodation could be found.

The procedure of having someone committed under the 1930 Mental Health act was a quite straightforward one. A family member – a father, mother, husband or wife – could inform the authorities that their relative had, in their opinion, gone insane. On their say so committal forms would be completed and signed, sanctioning that the person be taken into care initially for a period of observation. The police would usually be called, as Peter Barham describes in this example from Lunatics of the Great War:

John H. remembers the day when his father was taken away. He watched the Black Maria arrive with two policemen to take his father away he recalls. His mother signed the form afraid he might do something violent. John recalls his father chopping up all the furniture into little pieces and putting them on the fire until there was nothing left.

Two independent doctors were required to assess the patient and provide separate opinions. If they agreed then a simple form was completed and the person in question would then be taken in by the Infirmary staff. That was all it needed.

The five men reached the first floor landing. “You’ll be okay in here, Tommy,” said the officer who was handcuffed to him, “they’ll feed you up and look after you.” Tommy stared at him, thinking, after all I’ve done for you an’ all. He made no reply to the officer who he knew and looked down at the stone floor. There were people waiting in there, in that room, clever people who would fix things so I can go out and play again.

In his oak-panelled office on the first-floor landing, William Alexander Mair, the resident medical officer at the Infirmary, sat at his desk preparing the admission paperwork. Outside in the small waiting room were Primrose Bank’s master, Mr Ray; the matron, Miss Bennett; superintendent of the male mental ward, Robert Kirby; and chairman of the Infirmary Committee Board of Guardians, Hezekiah Proctor JP. Miss Bennett knocked and notified Mair that their patient had arrived and the group went through to Mair’s office. One of the officers handed over a folder to Mair who took it and checked its contents. The other officer released Tommy’s handcuffs and Mair thanked both men for their service and they were both dismissed. Tommy sat down in a chair in the middle of the floor facing the window, rubbing life back into his hand. The rain continued to bucket down outside. In front of Tommy was a long bench table and behind it five chairs. In the corner of the room the warmth from a coal-fire was welcoming. Just like home Tommy thought as he rubbed his hands in the warm glow of the fire.

Across the table from him, the welcoming committee sat down and prepared themselves. Proctor, Kirby, Mair, Ray and Bennett. Laid out in front of them was an array of files, books, forms and folders, notes and ink pens. Behind Tommy, the two white-coats sat quietly on each side of Mair’s door. Tommy maintained a fixed gaze at the pattern on Mair’s carpet. He coughed, his chest playing up again and holding his forehead asked for something to fix his splitting headache. Mair indicated to one of the white-coats to bring some aspirin and a glass of water, which Tommy thanked them for.

The formal admission procedure began with a welcome from Bill Mair followed by the staff introducing themselves and their roles. Through the blurred fuzz of the headache, Tommy was told why he was here and the reasons behind his admission. They all look so bloody miserable, not even a smile for the cat, he thought. He was to stay in Primrose Bank, Mair explained, for a period of up to fourteen days while they assessed his health and his state of mind. Under the Mental Health Act, fourteen days was the maximum period the hospital could detain a patient under a reception order. After that the patient could be released back into the community or an extension order from a court was required. If the patient escaped and was not recaptured within the fourteen-day period, the whole admission process had to begin again. Mair went on to explain that a thorough medical examination would be carried out to assess Tommy’s physical condition and over the following days there would be physical and mental tests, meetings with doctors and checks on his health, all to show that that he was getting better and responding to treatment. Only when the medical staff agreed he was fine would he be released.

Tommy shifted in his seat. He wasn’t listening though the headache was subsiding. Since his childhood he had hated small rooms, tunnels or being cooped up anywhere. He had to be outside. Ever since that day, the day that Jimmy died. The only thing on his mind right now was for this meeting to end and to get out of this place. He could feel the oak-panelled walls of Mair’s office closing in, like the walls of the pit and the bars of the tiny cell he’d just spent the night in.

Mair went on, explaining that they wanted to look after him, sort him out and fix him up, - the whole hospital line. Finally, he asked Tommy if he had any questions. The five committee members looked at him and waited for a response but none was forthcoming. Tommy simply shook his head and at that Mair stood up signalling the end to the meeting. Mair wished Tommy an enjoyable stay and confirmed that they all expected him to get well quickly.

The formalities over, Mair handed over to Robert Kirby and the two white-coats walked Tommy downstairs to the bathhouse where the Infirmary barber, Mr Fothergill, would give Tommy a shave, a haircut and a bath. Fothergill was a busy man. He knew all the male mental patients personally as they were not allowed to shave themselves. He certainly knew the man now sat in front of him, having seen him many times over the years, both in the newspapers and in the flesh in a claret and blue jersey at Turf Moor. Fothergill couldn’t believe his eyes as he ran the cut-throat razor up and down the leather strop. Tommy was asked his collar size and other measurements and a white-coat went off to the stores to get a set of male issue clothes while Tommy’s were sent to the laundry. After a shave, Fothergill ran a hot bath that was taken with a white-coat present. There was little privacy here. Patients were not allowed to visit the bathroom unaccompanied, not for the first forty-eight hours.

Two months prior to Tommy’s arrival at Primrose Bank, an occupancy audit of the mental wings was carried out by the Chief Medical Officer D. C Lamont who recorded that, “60 men were occupying 74 of the available beds in the male mental ward, 57 of them being long-stay patients… with 57 women inmates in the female ward.” So Tommy was not lonely on the ward that day. He was allocated a bed in the long male dormitory, and then taken down to the canteen for a meal. Peter Barham describes that one of the Infirmary’s first objectives was to feed the patient up: “the inmate would be put on a high-protein diet of eggs, milk pudding and beef tea and, depending on the patient, a dose of bromide or paraldehyde.” Following his meal Tommy was given a tour of the ward facilities and shown the day room. As with all patients, the days in the Infirmary were a common routine of sleeping and eating meals, with very few social activities. Essential in the daily regimen were the tests to check whether patients were fit enough to be released and could be trusted not to harm themselves, or anyone else.

After only two days in this environment, Tommy was restless. He hated rules, routines, confinement and the bars on the windows drove him mad. Hospital? More like a bloody prison camp… He was unhappy and wanted out. There was nothing to do and there was nothing to interest him: no football, no racing, no papers, no beer and no women. It was the match Saturday… There was nothing wrong with me anyway. Two weeks in here, in a bloody loony bin? He paced the floor like a caged tiger. He stood out like a sore thumb and the other patients pointed and stared at him. He shouted and swore back at them. First chance and I’m bloody out of here… He planned his escape. What am I doing here anyway with a load of bloody idiots? Bugger-all wrong, and what the hell was in the food?

He dragged a chair over to the day room window, stepped on it and climbed onto the window-sill where he sat and looked out through the bars. In the distance he could see farms, hills and green fields. Just like home. He closed his eyes and his mind wandered back to the game, down the years to the start of a new season.

He breathed in the sweet smell of the football field, the scent of freshly cut grass, the dressing room odours of tobacco smoke, hot sugared tea, sweat and liniment. The anthem of boot studs stamping on the stone dressing-room floor as he picked up the ball bounced it twice and shouted his war cry, “C’maan then,” before marching his boys out to do battle one more time. The increasing roar from the crowd as they emerged from the darkness into the light. Boyle, Dawson, Taylor, Bamford, Halley, Watson, Mosscrop, Lindley, Freeman, Hodgson and Nesbitt always at the back. Seeing the faces of the pretty girls waving and blowing kisses from the enclosure and winking at the ones he’d fancied. The huge swaying crowd all around the arena, squeezed tightly together, cheering him and his boys on, their faces as far back as the eye could see.

Then he was back where it all began, the cold winter harshness of Platts Common. Its grey, snow-covered coal heaps under a heavy sky. Saturday afternoon and a sleet-covered pitch at Hoyland. Hitting the opposing centre-forward hard and taking the ball off him. Easy. Away and up field with it. Out to the winger. Carry on running, the cross coming in. Leaping into the air and connecting with the frozen ball with his temple, BANG and watching the missile fly straight through the goalkeeper’s outstretched hands. The cheers from the soaking wet handful of spectators as the ball filled the back of the net. Wiping the blood, the mud and the slush from his forehead with the back of his hand. Laughing, soaked to the skin. Home afterwards and a hot bath in front of the fire. He’d loved every second of it. Then there was the time when he’d played against…

He was abruptly wakened from his dream, a hand on his shoulder pulling him down from the window-sill.

“Come on Tommy, time to see the Doc,” said the white-coat.

“Piss off, I’m not goin’.”

He put his fists up and started swinging. He was being awkward again so one white-coat dragged him down from the window while the other pinned his arms by his side and fastened the waist belt around him, locking his wrists down by his sides. Then they frogmarched him downstairs.

“More bloody stupid questions? I’m saying nothing. There’s bugger all wrong with me I tell thi!” he shouted.

The night-time was worst. Horrible things happened to people in the dark. In the dim light of the groaning, coughing dormitory, the haunting nightmares returned. The same terrible visions, over and over. He was miles underground in the bowels of the pit, in the dark, his lamp out. The unforgettable sound of splintering timber roof-props, the crushing, rumbling sound as the roof caved in. The smoke and the dust clearing. His best friend, Jimmy Leach, a boy just like him, only his arms and head visible, reaching out, crying for him to help, the rest of his body trapped and crushed beneath huge boulders of stone. “Help me… get me… out Tommy…” the boy gasped. He clawed at the rock with bare hands, his fingers bleeding, but with no shovel or help it was futile. The look on the boys face. He watched, helpless, for perhaps seconds as the roof crushed down harder and harder and Jimmy Leach choked to death on his own blood. He’d tried but there was nothing he could do. Nothing. He’d tried, again. He shouted for help. He heard them coming. But not men. They could smell the blood and the fear. The army of huge pit rats coming for him and Jimmy Leach. They ran over him to get at their prey. Hungry, slithering, gnawing, he kicked at them with his feet…

Another scene: a smashed landscape that had once been a beautiful city. Ypres and its broken buildings, trees that should have been in leaf turned to matchwood. Shells tearing across the night sky and exploding all around. Looking down and seeing his boot oozing blood through the lace holes. His pants in shreds, covered in blood, all his kit gone and the fear of gangrene setting in. They were here again, the scavenging rats, grown fat on the bodies of his dead mates, coming again, a whole army of them, coming for him… The final reel. He was standing in the doorway of a small bedroom lit only by candlelight. A child, his little girl, lifeless and cold. The most beautiful and precious thing in his whole world gone. His heart ripped out.

He was wide awake, sweating and gasping for breath. Throat dry as a bone. Screaming pains in his head again. The bars at the windows. No way out. The horrible visions gone for now, replaced by a rage and a desperate need to get out of this place. He had tried escaping the night before but another inmate had shouted for the white-coats, so after they’d gone he’d gone over and thumped the daft sod. They’d heard his screams and came running back. He’d been returned to bed, restrained, sedated, with a white-coat posted at his bedside until the calming peace from the morphine eventually came.

Tommy Boyle’s stay at Primrose Bank wasn’t long. Five days after his arrival he was back in front of Bill Mair and the welcoming committee. There was nothing more they could do for him here. The institution wasn’t equipped for violent cases, though it did possess its own ‘treatment’ rooms that had been refitted in late 1931. Mair completed his report and wrote that Tommy had been, “striking other patients and staff”. Mair’s mind was made up. It was clear to him the patient was not fit to be released and wanted him off the books. He wasn’t alone. The Chief Constable also wanted him removed, as far out of town as possible. The press had been sniffing around the past day or two and asking questions.

“We don’t have the facilities you need here, Tommy; you need special care. We’re transferring you to another unit,” said Mair.

Transfer?

Along with Bill Mair and Robert Kirby, there were three new faces in the room that had not been present five days before. Patients who were to be admitted to a mental institution had to be certified as insane by two independent doctors and a Justice of the Peace. James Alfred Sampson JP was present and had already co-signed the order made out by Bill Mair that was addressed to the superintendent of the forwarding institution. Mair was putting the finishing touches to his report.

From across the room, Tommy looked on to see them in their huddle, gathered around Mair’s long table. They all looked serious, asking questions, their voices low and difficult to make out. Finally, they nodded in agreement and looked up. Forms and pieces of paper were signed, contracts exchanged.

Looks like a deal.

They said he was being transferred. But to which club?

“Whittingham,” was all he’d heard them say.

“Who the soddin’ hell are Whittingham and what bloody league do they play in?”

But they were not joking.

And so on Monday 29 February 1932, five days after arriving at Primrose Bank Infirmary, Thomas William Boyle, forty-six and of no fixed abode, Burnley Football Club’s most successful captain in its history, made the final transfer of his career. He was bound for Whittingham Mental Hospital, the former Lancashire County Lunatic Asylum, near Preston, where he became patient number 24281, a number he would become for the rest of his life.

Chapter 2: Roots

Pat Boyle, Tommy’s father, came from Collon, a small village in County Louth in Ireland, about ten miles from the east coast. Pat was born in 1847 to parents Patrick and Bridget Boyle and came into the world during the period of the Great Famine. Like many Irish Catholics, Pat Boyle chose to emigrate for a better life. He arrived in England in his late teens, in the middle of the 1860s and his younger brother John followed him across the water ten years later.

Following the short crossing by steamship from Drogheda, Pat Boyle arrived at Liverpool docks. On arrival he had a number of options. He could stay in England and make a career here or, if he had the money, for five pounds sail steerage class on the month-long voyage to America. For another ten pounds he could have gone as far as Australia. With the Civil War raging in America from 1861–5, England was probably the safer option. The economy was booming and labour was in short supply. The industrial revolution was in full swing, driving the growth of the British economy which led the expansion of the Empire across the globe. But this expansion was not possible without a driving source: coal, vital in fuelling Britain’s growing industrial base. Coal for the railways and the steel foundries. Coal for powering the thousands of factory and mill engines and for fuelling the British navy patrolling the oceans protecting her interests. The abundance of rich coal deposits in the north of England were crucial in sustaining Britain’s place in the world. The nation owed much of its status to the men who dug the black gold, who spent their lives underground in cramped, dangerous conditions, putting their lives at risk each time they descended into the darkness. From the mid-nineteenth century the numbers working in the coal industry grew rapidly and the young Pat Boyle was attracted by the wages the mining industry offered, twice as much as he would have earned working the land back in Collon.

Around the same time that Pat Boyle sailed for England, a young lady, Ellen St. John, made the same crossing. A year younger than Pat, Ellen was born in Tulla, a small village in County Clare, one of the counties worst affected by land evictions.

Pat and Ellen met in Wigan where Pat was working as a coalminer and Ellen as a cotton worker in the mill. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Wigan was booming. There were fifty-four collieries in the town by 1855 and up to 1,000 pit shafts, leading one town councillor to remark “a coal mine in every backyard was not uncommon in Wigan”. Pat Boyle would not have struggled to find work, and for Ellen the cotton mills in Wigan would equally have been in need of workers. The couple fell in love, and set the date for their wedding as 19 November 1870, at St. John’s Chapel in Wigan. Pat was twenty-three and Ellen, twenty-two.

Four days before the wedding, there was an explosion at Plattbridge, a pit three miles from Wigan. Twenty-seven miners were killed in the blast. That disaster had followed a similar explosion at the nearby Haydock colliery a year before in which fifty-nine men had lost their lives. Pat Boyle soon discovered that compared to working on the land back in Ireland, mining, though it paid more, was a much more dangerous game. Personal safety may have been one concern on his mind just a few months after getting married, but his main reasons for seeking pastures new were probably the higher wages the Yorkshire pit owners offered and the prospect of getting one of the new pit cottages being built around the collieries. This would be a big improvement on the shared accommodation the Boyles had in Lyon Street and it would mean Pat and Ellen could settle down and start a family.

Barnsley

Originally a major centre for the wire- and linen-making industries, by 1871 Barnsley had become the epicentre of the coal-mining industry in South Yorkshire. Coal had been dug in the area since the Middle Ages and both Silkstone and Orgreave are mentioned in the Domesday Book. Six months after Pat and Ellen were married, the 1871 Census showed Pat was lodging at Number 6, Court 1, Sheffield Road, Barnsley – a boarding house. When Pat arrived there were sixty-three pits operating in Barnsley employing thousands of men. He was employed as a colliery labourer so when he moved to Barnsley he had to start again at the bottom of the employment ladder. Of the twenty-six other people named at the same address in Sheffield Road, half were Irishmen working in the pits.

Ellen joined Pat in Barnsley six months later and the Boyles’ first child, Elizabeth, was born in Barnsley in April 1873, almost next door to where Pat had lived when he arrived two years before. Elizabeth was followed a year later in 1874 by Mary. The Boyles’ first son, John, was born in 1876, and by 1880 a fourth child, Margaret Ellen, was born.

Figure 2. Platts Common 1893 (Ordnance Survey with permission)

Figure 3. Platts Common 1905

Platts Common

By 1881 the Boyle’s had moved out of Barnsley to Platts Common, a little village just a few miles south. The village was overshadowed by the recently opened Hoyland Silkstone Colliery bringing hundreds of jobs to the area. The colliery was part of the Rockingham Mining Group owned by Earl Fitzwilliam. Rockingham consisted of four of the biggest pits in the South Yorkshire coalfield: Rockingham, Wharnecliffe Silkstone, Skier Springs and Hoyland Silkstone. The village of Platts Common sits at the junction of the Wombwell and Barnsley roads. In the village there was a grocer, a shoemaker, two beer-sellers, a chapel, a cricket ground, a bowling green and a pub, The Royal Oak.

After moving to Platts Common, two more family additions arrived. A fourth daughter, Catherine was born in 1882 and the Boyles’ last child arrived on a cold winter’s day on Friday 29 January 1886 at Number 5, Hagues Yard. Pat and Ellen named him, Thomas William after Ellen’s grandfather.

Hagues Yard was directly across the road from the pit gates. It was a block of twenty-four dwellings that shared a common yard with communal toilets and outdoor wash-house facilities. The houses in Hagues Yard were the oldest in the village. They consisted of two rooms and a pantry that offered little in the way privacy for a couple with six growing children. There was cold running water but no gas or electricity and the heating and cooking facilities were provided by a coal-fuelled, cast-iron range.

The day baby Thomas was born was bitterly cold. The Meteorological Office report for the week ending Monday 1 February 1886 read:

The weather has continued in an unsettled condition. Cold rain, sleet and snow with lightning and thunderstorms in different parts of the Kingdom. Temperatures between 1 and 4 degrees above freezing. In York the weather never got above 40 degrees Fahrenheit and the previous week has rained six days out of seven.

As the young Thomas arrived in Platts Common, in politics, Lord Salisbury tendered his resignation to Queen Victoria after being summoned to Osborne House, while miners in France were demanding an increase in pay. In football, the Leeds Mercury reported that the Leeds Parish Church football team were continuing their northern tour and had played Kendal Hornets the previous day. The game had ended goal-less, the reporter blaming the visitors’ tactics, for “repeatedly lying on the ball when it became loose”.

A month after he was born, Thomas William was baptised at St. Helen’s Church in Hoyland. The Catholic service was conducted in Latin and the baptism register shows his godparents as neighbours John and Sarah Cummins.

The nearest Catholic school for the Boyle children was a long walk away to the nearby village of Stubbin. Erected in 1864, the village school was run by schoolmistress Miss Jennie Nolan and accommodated up to 200 children, so would have had two or more teachers working there. School focused strongly on the three ‘R’s and Pat Boyle, who could both read and write, was determined to see all his children got an education as his own father had insisted back in Ireland. After the creation of the Hoyland school board in 1873, two new schools were built, one at Hoyland Nether and the other at Hoyland Common. St. Helen’s Roman Catholic school was built in 1897 when Tommy was eleven and it’s possible he moved here for his final year of schooling as it was much closer to home.

After school, children would play football in the street with a ball made of rags. Street football was a disturbance of the peace, and was one of the principal targets for police prosecutions. But Tommy Boyle wouldn’t be caught; he was too quick for them.

In his final year at school at age twelve, Tommy spent half of his day at school and half at work in what was known as the Half-Time system. He would spend his half-days on the pit top sorting coal, possibly working with his elder sisters before eventually going underground with his brother and father once his school days were over. Starting work at the pit would have been a terrifying experience for a twelve-year-old. In appearance, the pit boys resembled miniature versions of their fathers, wearing a jacket, pants, boots and a cap. They would be allocated a job working with the pit ponies as David Tonks describes,

At twelve a boy became a pony driver, leading a pony as it pulled a set of tubs underground. As he got stronger, at 16 he became a ‘putter’, and moved to supplying the miners with empty tubs and moving the full ones. Later he would become a hewing putter and at 21 a hewer, working at the face cutting coal with a pick.

The morning shift began at six-thirty a.m. If the men were a minute late they’d be sent away and lose a full day’s pay. For a hewer like Pat Boyle, the best-paid job in the pit, he would receive around three shillings and ninepence (eighteen pence) for ten hours labour.

The Conditions

For the first couple of days, Tommy would probably have lost his breakfast as the cage flew down the shaft making his ears pop. At the pit bottom the men would call at the blacksmith’s shop to pick up their tools: a wooden pick made of ash or hickory with a steel tip and a short shovel (until the start of World War I, eighty per cent of coal was cut by hand). The men would then make the long journey to the coalface, often taking up to an hour for which they were not paid. On arrival they would strip to the waist to cope with the heat and humidity, then stoop, crouch or lie on their sides for hours on end to rip out the coal from the seam. They would emerge at the shift-end looking like statues, coated in a layer of coal dust that stuck to the pores, got in the eyes, ears and nostrils and attacked the back of the throat. There were no toilets, no drinking water and no prospect of fresh air until the end of the shift. Rats and mice ran in packs and came in various shades from albino to black. The miners said some were as big as cats, with huge, sharp teeth. These creatures were known to steal the men’s lunches, if they were not in sealed ‘snap’ tins.

The job demanded and made physically strong men. The hewer would develop great upper body strength. Alongside the hewer, the putter would shovel and fill the tubs and he needed great strength to get the heavy tubs moving. This involved leaning forwards at an angle with both arms around the tub, head down and pushing forward, often barefooted to give better traction until the tub began to move. Once they had got the load moving, momentum took over until eventually the rope boy with his pony took the coal tubs to the pit bottom. The putter would develop solid upper body and leg muscles – perfect development for an athlete, especially a runner. The putter would regularly catch his back on the low roof, leading to ‘shirt buttons’ as the skin scraped off along the vertebrae, leaving a blue scar as the open wound mixed with coal dust.

The South Yorkshire coalfield experienced some of the worst disasters in mining history. At the Huskar mine in Silkstone in 1838, twenty-six children, including eleven girls, three of whom were only eight, and fifteen boys drowned during a thunderstorm as they attempted to escape rising flood waters. This incident led to the Royal Commission ending the employment of women and children underground from 1842, though it carried on in some pits. In February 1857 at the Lundhill mine, an explosion killed 189 men and boys, and before Christmas in 1866 an explosion ripped through the Oaks Colliery in Ardsley just to the east of Barnsley, killing 361 men and boys. Only six miners from the entire shift escaped alive. The following day as mine rescuers tried to reach survivors, a secondary explosion killed twenty-seven of them. These events and dozens like them had a massive effect on the local pit village communities, with hundreds of families losing husbands, brothers and sons.

The accident records for the Hoyland Silkstone colliery show some seventy-seven men were seriously hurt or were killed between 1886–1911, the youngest just thirteen years old and the eldest aged sixty-six. An injury to one particular miner at another Barnsley pit was reported in an article in the Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser in 1893:

Yesterday evening Patrick Boyle, a miner from Barnsley was brought home from the New Oaks colliery near Barnsley where he had been buried six hours and was believed by his friends to be dead. Boyle was working when a large fall of roof buried him and constant falls prevented him from being rescued. His head was bared and his body protected by timber until he was extricated. Strange to say he was only cut about the head and was able to walk when he got home.

It is unclear whether this was Tommy’s father as New Oaks was some distance from Platts Common. It is more likely that Pat Boyle was employed just across the road at Hoyland Silkstone, but we can’t be certain. Whichever Pat Boyle it was, he had certainly been very lucky to survive his ordeal.

In facing the daily threat of death from roof falls, gas, fire, explosions and floods, miners were and remain a unique band of workers. They face the harsh conditions together with a black sense of humour and a special bond exists among them, a camaraderie unknown in other professions and probably only equalled in the armed forces. Tommy would have experienced this in his formative years. Miners stick together, work together, drink together and when things get tough, fight together. Improvements in working conditions and pay were only won through a hard struggle which continued down the generations, mainly through strikes, which brought great hardship to the men and their families. As a consequence of their actions, they faced lock-outs, scab labour, home evictions, and police and military intervention. Though working conditions improved with the passing of the 1872 Mines Act that gave the miner a ten-hour working day, it was to be another fifteen years before miners enjoyed a half-day off on a Saturday and a working week of fifty-five hours. As their struggle continued, by 1900 the working week for miners was reduced to forty-five hours, by which time the fourteen-year-old Tommy Boyle had been working underground for two years

Figure 4. Hoyland Silkstone Colliery, Platts Common.

Violent times

The Boyle family would have experienced their share of ‘the struggle’ through a number of disputes, many of them violent ones that took place in Platts Common.

In 1887 Hansard recorded:

On Monday both excitement and curiosity were caused by the arrival at Hoyland Silkstone of a staff of police from Barnsley, who proceeded to search about 500 of the men and boys employed at the colliery there. It appears that about 9 o’clock in the morning, a girl named Wild, who was picking coal from the rubbish heap of the colliery, found a loaded pistol amongst the dirt which had been thrown out of a corve… The pistol had a screw barrel, and was indifferently loaded with powder and ball, but no wadding or paper had been used for ramming the charge home. Nothing of a suspicious character was found, however inquiries are still being made in order to find out for what purpose the pistol had been taken down the pit. (Hansard, 6 April 1887)

In the summer of 1893, the coal price had collapsed by thirty-five per cent. As a consequence miners faced a twenty-five per cent reduction in wages and were locked out if they refused to accept the cut in pay. Any striking miner was warned he would face eviction from his home if he joined the strike. In South Yorkshire, ‘The Great Lockout’ as it was known, lasted five months and was one of the most violent and bitter disputes in mining history. Author David Hey wrote that in some villages, including Hoyland and Orgreave, the militia were called out to quell the disturbances. Four squadrons of Dragoons and a squadron of Lancers were stationed at Wentworth Woodhouse on the Earl Fitzwilliam’s estate on standby to maintain order. The Earl, a joint owner of the Rockingham mine group, was against any of his men being union members. The Riot Act was read at Featherstone near Wakefield but it didn’t prevent troops firing on striking miners, killing two and wounding sixteen. The bitter dispute dragged on, attitudes on both sides hardened and it descended into what became known locally as The Rockingham Riots. Platts Common was caught up in the dispute as the Daily Commercial Advertiser reported in November 1893:

… some thousands of miners proceeded to Hoyland Silkstone colliery and completely sacked the place, seriously injuring, with bludgeons, Mr Fincken the managing director and others. The vast body then proceeded to the Rockingham colliery of which Mr Chambers is managing director and made a most furious attack upon the premises as well as upon the persons found above ground. After drinking the contents of three casks of ale and availing themselves to a dray load of mineral waters, the rioters deliberately set fire to the offices and adjoining buildings.

A small boy carried the news to Hoyland Common where shopkeepers hurriedly put up shutters. The strike dragged on for four months before a meeting in late November 1893 agreed that the men could return to work at their old wages. All this provided a canvas to the conditions Pat Boyle and his family faced as they tried desperately to eke out a living underground.

Sport in Barnsley

When the shorter working week arrived in 1887, miners had long earned their Saturday afternoons off. The men could develop other interests, such as tending their allotments, racing pigeons, spending the afternoon in the pub or attending sporting events. Sunday was the Lord’s Day, strictly reserved for putting on your Sunday best, going to church and serving God. Practically everywhere was shut apart from the church. After a short Saturday morning shift, the afternoon became devoted to sport. In summer the men in Platts Common would play bowls or cricket. Rabbit coursing was popular and took place in the fields next to The Royal Oak pub with larger competitions held at Queens Fields in Barnsley. And in winter there was football.

When Tommy was a year old in 1887, the twenty-four-year-old Tiverton Preedy arrived in Barnsley fresh from theological college to take up his post of assistant stipendiary curate at St. Peter’s Church, just a stone’s throw from Sheffield Road where the Boyle family had lived. Two years before, Preedy had trained in Lincoln under his mentor, Edward White Benson. A former assistant master at Rugby School, Benson was a contributor to the development of the Rugby School football rules and believed strongly in team sports like rugby with its morals of team spirit, fair play and ‘Christian manliness’. Clearly influenced by Benson, who went on to become archbishop of Canterbury, Preedy arrived full of optimism. The Parish of St. Peter’s was one of the poorest in the town. While walking back to St. Peter’s one day, he passed a pub and overheard some young men talking about forming a football team. Where rugby appealed to the more affluent, football was the more popular, unruly game of the streets. Preedy realised that through football he could reach out to the young, working-class men he saw hanging around outside pubs with little to do in their spare time.

Preedy chose the name Barnsley St. Peter’s Football Club for his community project and at the club’s inaugural meeting on Tuesday 6 September 1887 he became the club’s first financial secretary. His first priority was to find somewhere to play. From the steps of St. Peter’s looking north-eastwards across Doncaster Road stood a valley of open fields, an area known as Oakwell. He approached the Senior brothers, owners of the Oakwell Brewery to which the fields belonged, and asked whether he could hire a field for a football match. After an initial refusal Preedy persisted and the brothers eventually granted his request. Eleven days after the inaugural meeting, on 17 September, Barnsley St. Peter’s first match took place. Three years later, the club began its first season in the Sheffield and District League. Preedy must have been a keen footballer in his day as he is mentioned in an article entitled ‘Is football dangerous’ in the Pall Mall Gazette of March 1892:

On December 10 (1891), the Rev. Tiverton Preedy was running in the football field at Barnsley when he struck his forehead with great violence against a wooden beam. He was felled and bled profusely from a severe scalp wound.

Fortunately, Preedy survived his run-in with the goalpost, but in 1896 he left St. Peter’s for a new post in Islington where he continued his work in developing young men through sport, focusing on boxing and wrestling, with some of his protégés selected for the 1908 Olympics. His fondness for Barnsley remained throughout his life and he made regular return visits to see how his community project had developed. Following their years in the Sheffield and District and the Midland Leagues, Barnsley FC, along with Glossop North End and New Brighton Tower, were elected to Division Two of the Football League in the summer of 1898. Arthur Fairclough became the first Barnsley secretary, staying at the club for three seasons before leaving in 1901. He then returned three years later for a second period, one that would see Barnsley reach two Cup Finals and sign a certain youngster from Platts Common.

The Barnsley and District Football Association was formed in September 1893 after breaking away from the Sheffield Association. Once again the Reverend Preedy was influential in matters. One of the new Association’s objectives was to “encourage local talent”. A year later at the first annual general meeting, some sixty clubs were represented and a Scholars’ Cup competition for local schoolboys was established. Sadly, this competition was discontinued in 1895, the minutes reporting “the schoolmasters having insufficient time”, but in its place an under-sixteens junior league was set up. Hoyland had a number of teams representing collieries, ironworks, churches and pubs and hard rivalries existed between them. Hoyland Silkstone pit had its own football team and there were five other football teams in Hoyland: Hoyland Rock, Hoyland Town, Hoyland Nether, Upper Hoyland and Hoyland Common Wesleyans. The whole area must have been football crazy!

Chapter 3: The Boy from Platts Common

Then up lads, and at it, though cold be the weather;

And if by perchance you should happen to fall,

There are worse things in life than a tumble in the heather,

For what is this life, but a game of football?

– James McConnell

It was an ordinary working day in the middle of August 1899, but a tragic day that would shape the young Tommy Boyle’s future. The men from the village arrived for the morning shift as usual at six thirty a.m. Among them the Boyles; Pat, Tommy and John and the Leaches – Jimmy, his father and three brothers – all descended in the cage together. Tommy and Jimmy were best friends and were employed as rope-boys, pulling the full coal tubs along with their ponies. At the pit bottom, the men collected their tools from the blacksmith’s shop and the boys went on their way to collect the ponies from the stables. A couple of hours into the shift, Tommy heard a loud rumble in the tunnel ahead where Jimmy had just taken a full load of coal. As he ran up the tunnel, clouds of smoke and dust engulfed him. He couldn’t see a thing. He called out for Jimmy as the dust began to clear but he soon realised he was too late: