Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

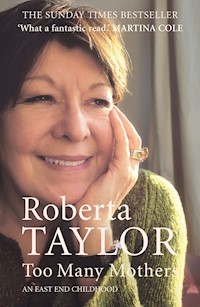

'I was born in a sideboard.' So begins Roberta Taylor's bittersweet memoir of her early years, a book that proves beyond doubt that real life is stranger than any soap opera. It's Boxing Day, 1956 in East London, and it's freezing, inside and out. Roberta, aged eight, sits in the kitchen in her overcoat, determined to make herself invisible, watching the shenanigans of the grown-ups. Her granny, Mary, reigns over the house with an iron will and an eye to the main chance. Roberta's cousin is on her hands and knees at the parlour grate, trying to retrieve grandad's dentures from the coals, dragging her coat in the dust. It's too cold to hang it up by the front door. Besides, Granny Mary makes no exceptions when it comes to the occasional light thieving. Aunt Doll learns that the hard way. Not even a padlock kept Mary from stealing Doll's wedding presents, although nobody can understand how she got the back off the wardrobe without Doll noticing. Too Many Mothers is a portrait of an embattled extended family at war with itself and the outside world. From petty crime to pet monkeys, tender romance to shameless emotional blackmail, illegitimacy, adoption and even murder, Roberta Taylor has written a kaleidoscopic and unforgettable memoir of her family and her early life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 356

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Too Many Mothers

Roberta Taylor is one of Britain’s most respected actresses. A member of the Glasgow Citizens’ Company, Roberta has worked for years in theatre. In 1997 she became a household name when she played Irene Raymond in the BBC soap EastEnders. She now stars in ITV’s The Bill. She lives in London.

‘A marvellous book! I couldn’t put it down. Roberta Taylor brings that era and that part of London zinging to life with such an authentic voice. It’s so rare to find East Enders given their real voice.’ Helen Mirren

‘A gut-wrenching memoir that still has you gasping with laughter. I don’t know of any other book that captures the stink of poverty like this and still celebrates. A hell of a book. Give it to your prosperous friends who wonder what it’s all about.’ Frank McCourt

‘The Taylor family’s mid-20th century version of East End life is discomfortingly close to Dickens’s depictions of survival in the slums a century earlier. All the same there is a tremendous generosity and a good deal of dark humour in Taylor’s telling of her family’s story … Reading Taylor’s prose is like listening to a fascinating and feisty friend.’ Melanie McGrath, Evening Standard

‘As mordantly funny as it is affecting.’ Paul Bailey, Independent

‘Engrossing’ Michael Moorcock, Guardian

‘Compelling’ Mark Sanderson, Sunday Telegraph

‘The actress familiar to fans of EastEnders and The Bill with a gob-smacking memoir of her early life and the extended family who brought her up. This included the wily matriarch Nanny Mary and a host of aunts: Doll, Flo, Violet and Carol. Like the most far-fetched of soap operas, except you couldn’t make this up. It would be a brilliant Radio 4 “Book of the Week”.’ The Bookseller

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Atlantic Books.

This ebook edition published by Atlantic Books in 2012.

Copyright © Roberta Taylor 2005.

The moral right of Roberta Taylor to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Some of the names in this book have been changed. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781848872561

Atlantic Books Ormond House 26/27 Boswell Street

For Elliot, Jo and Ellis

The Boxing Day Table

Contents

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER ONE: Mary

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER TWO: Mary

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER THREE: Mary

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER FOUR: Mary

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER FIVE: Mary

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER SIX: Mary

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER SEVEN: Flo

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER EIGHT: Doll

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER NINE: Vi

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER TEN: Win

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Robert

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER TWELVE: Carol

Boxing Day 1956

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: George

EPILOGUE: Roberta

Boxing Day 1956

Mary eased her heavy legs out of bed and sat up. The room was like an icebox. Her feet fumbled around in the dark and found the torch. It was five o’clock in the morning and she had a hectic day ahead of her. The corpse that had been lying next to her gave off a fart which blew Bob into a more comfortable position. His gaping, gummy mouth closed with a damp smack. She shone the torch over the bed and grabbed one of the overcoats that masqueraded as blankets, shivered herself into it, and stared at him in the brutal pencil of light.

‘His face has eaten him,’ she thought, and remembered the different face and body she had married all those years ago.

CHAPTER ONE

Mary

Mary Roberts, née Burke, started smoking when she was nine years old, had her arms tattooed by the age of fifteen, and married my grandfather, Robert Victor Roberts, at eighteen. She shuffled the facts of her life to suit her intentions. She swore that she was born on 8 August 1900 to an Irish tinker family. Her birthday was always celebrated on the eighth of August, even though her birth certificate insists that she poked her nose into the world on 13 May 1900. Like a brass band on a Sunday morning the speed and energy of the cockney accent cooked very nicely thank you with the southern Irish tones and vernacular of her parents. The scenic route of her life would not have much to do with geography; she lived and died in the East End of London.

Mary sauntered away from her family home, away from the slums of Poplar, without so much as a by-your-leave, in February 1918, and walked four grim miles east to Bob Roberts’s mother’s house in West Ham. She was pregnant. How and where Mary met Bob had never cropped up. He came from a better class of cockney, apparently. Perhaps they washed more often, had antimacassars, books, and sat at the table to eat. Mary’s children were in no doubt that it was the Roberts side that was the civilized side.

Would he marry her? Of course he would. She was gorgeous. Pale skin, green eyes, a mass of complicated red hair, and a cheeky little figure with a temperament to match. A Shetland pony in human form.

They whispered their dilemma in the privacy of Clara Roberts’s front parlour.

He couldn’t marry her right at that moment, he had to return to sea in two days’ time. She hadn’t reckoned on his going away so soon, and neither had he, but there was a war on and the Merchant Navy had an important job to do.

If Bob and his brother William managed to survive, they would be away until Christmas at least.

‘In this situation, it’s all hands on deck,’ he tried to explain to her.

All she owned she stood up in. She didn’t look that much different from most poor girls of the time, but for her hair, her swagger, and the minx-eyed look she’d give instead of a straight answer. Leaving her, Bob braced himself and walked to the scullery.

His mother and brother took the news better than they might have done in peacetime. Clara had bigger things to fret about now. Her boys were going away and she couldn’t guarantee she would ever see them again.

Today was Mary’s first meeting with Clara and William, and her first meeting with the inside of their house. She had sidled past a couple of times last year, out of curiosity, when she had been waiting to meet Bob at the street corner.

Her own living arrangements had consisted of a bug-infested tenement, surrounded by thieves and vagabonds. The daffy of fourteen Burkes shared one and a half rooms, one cold tap and a black cauldron on the open fire stewing lumpish, watery broth. An iron double bed catered for her mum, dad, and the three youngest toddlers. Two large mattresses on the floor slept the nine other Burkes: girls in one, boys in the other. She had slept with somebody else’s feet in her face all her life.

Here, she was in a real house. Mary sniffed her future in the beeswax of the parlour. On the mantelshelf were two postcards with camels on them, a wooden-framed photograph of Bob and William in matching dark overcoats, a pair of pewter candlesticks, and a small metal candle-snuffer. The shelves on the wall to the left of the fireplace were home to a pink flowery tea set, the six cups, face down in their saucers to keep out the dust, separated by the round fat teapot. On the top shelf, taking pride of place, she eyed up an ancient-looking carved ornament of a withered old man.

She ran her fingers over the highly polished sideboard against the opposite wall and looked at the squat wooden clock sitting on a lace runner.

Three o’clock in the afternoon.

Thursday, 28 February 1918, she reminded herself.

Stealthily she opened the sideboard drawers. In the left-hand drawer, packed to the gunwales, lived pieces of yellowing lace and neatly folded gentlemen’s handkerchiefs. The right-hand drawer contained a pile of formal-looking documents, a pair of scissors, some buff envelopes, and half a dozen collar studs. Right at the back of the drawer she spotted something else. A roll of large white five-pound notes gripped by a rubber band.

At the sound of the Roberts family coming towards her Mary quickly re-arranged herself as a scrap of humanity that only the coldest heart could ignore. The money stayed in the drawer. Clara was first in, followed immediately by her two sons. William had his arm around his younger brother’s shoulder. It looked as if Bob had been crying.

Boxing Day 1956

‘I, Mary Burke, a very, very bad Catholic, take thee Bob Roberts, my religious Protestant ... I even married you in your Proddy church didn’t I?’

Mary left him to his slumber.

It had not been a restful night for her. She had floated between the dead and the living, in that fitful, pointless kind of sleep. Footsteps across her ceiling all night, quietening down babies and toddlers, had made her ratty.

She hadn’t dreamt of the Chinaman in donkey’s years.

Mary’s children: between 1918 and 1943 she had laid her seven eggs. She could have laid more if she’d persevered. I am the epilogue of her life. Her granddaughter.

CHAPTER TWO

Mary

Mary never went home again. And no one came looking for her.

Tea was brought in by William, Clara held her hand and lowered her into the armchair, and Bob rolled her a smoke. Clara told her what they had decided would be for the best, for all their sakes. If she agreed, of course.

She more than did.

Mary stuck to her story, that her parents had thrown her out. No, there was nothing to go back there for. It was time for the grand tour.

Between the parlour at the front and the scullery out the back was Clara’s bedroom. She would sleep here with Clara for the next two days, until the boys had gone off to sea. Mary had never seen a bed so clean, so squishy. Four large white pillows with lace edging sat like sentries on top of blankets over blankets over more blankets, topped with a shiny golden fattipuff eiderdown. There was more than enough room for the two of them; she thought of the absolute luxury of all that bed for one person. Clara hadn’t shared her bed for ten years. The polished lino had green woolly runners on either side of the bed to keep your feet warm when you got up. The room was almost identical in shape to the parlour, with an identical fireplace. In the alcove stood a wardrobe with a full-length mirror for a door. The other furniture was a small round table by the window and a straight-backed wooden chair with a rattan seat by the fireplace. The fire was neatly laid but not yet lit. She peeked out of the big square window and saw that it looked onto the backyard. The six shirts and two towels on the washing line were stiff with the cold.

Mary was delicately manoeuvred into the back room to be shown the stove, the big butler-sink with its bleached wooden draining board, and the pots and pans. Something hearty was simmering slowly in a big pot on the gas, warming the whole room. Under the window was a white enamel-topped table and four chairs; an open carton of salt sat in the middle of it. They didn’t bother to take Mary into the yard, just pointed to the privy and asked if she needed to use it. She didn’t. It was too cold to go outside unless really necessary.

The upstairs didn’t seem to match the downstairs in size. It was up here that Clara explained what was going to happen. Once the boys had left, William’s bedroom would become Mary’s scullery, and his bed would be moved down into Clara’s room. A sink and a stove would be put upstairs, and Bob’s room would become their marital bedroom. Each bedroom had a small iron fireplace, so it wouldn’t get too cold. Lugging the coal up would be a bit of a hike, but they all decided it was manageable, even for a girl.

Mary gave off a dazed look while all this was going on, disguising her fleetness of tongue and brain. She looked pliable. How else could an innocent, unmarried girl get pregnant? So pliable, in fact, she allowed herself to be bathed in the zinc bath which had been dragged in from the yard, and she even let Clara unpin her hair and search for nits. Clara found none. While all this female cleansing was going on, William and Bob were placed in the front parlour.

With sterilized hair and body, she was given a set of Clara’s undergarments and a long grey skirt with matching top. She was allowed to keep her own boots, for now. The women were almost the same size, except that Mary was about two inches taller. The long skirt was not as long as it should have been. She plaited her damp hair into two braids. It would dry with a pretty kink in it and by tomorrow morning appear curlier than it really was. Everything Mary had arrived in was put on the fire in the front parlour, rag by rag, and burnt. She had shed her old skin, and was preparing a new, thicker one for the future.

After supper of lamb and potato stew, she helped Clara with the washing up in the scullery while William and Bob organized the bedtime fire in Clara’s room and hot-water bottles for themselves. Bob’s hot glances pierced the back of Mary’s neck, she felt his arm brush by her breasts to get to the tap. She never looked at him, never said a word to him.

The comfort of the fire, the armchair, and the hot milk made her eyelids and head droop as she sat in the parlour with her new family. They had all been talking about what was going to happen tomorrow. She drifted in and out, thinking of those fivers in the drawer right next to her.

Bob was given permission to walk her into the bedroom, kiss her goodnight, and put her to bed. One of his mother’s nightdresses was waiting for her, laid out on the golden eiderdown. As he soaked up her lovely perfume of carbolic, Mary gave him a tired wink, a little kiss on the mouth, and sent him on his way.

Her last gasp of energy was spent taking off one set of new clothes and donning another. She took her time getting into bed. Mary wanted to luxuriate in every limb being embraced by the sharp prick of the cold linen sheets, followed by the cosy comforting weight of all those blankets. Then she conked out. She dreamt she was flying on a huge five-pound note, a magic carpet riding the breeze across the continents of the world.

The next day brought a trip to Stratford Broadway on the electric tram. William paid the fares. The Broadway was dominated by Boardman’s, the fancy outfitters: three vast floors of clothing for every occasion. Bob and William went off for a stroll round the shop, while Clara fitted Mary out with a warm grey coat, two frocks, and a pair of ladies’ buttoned boots. The frocks and coat were as shapeless as they could find, to make room for her pregnancy. Next stop was the underwear department, where two of everything was needed for Mary and, Clara said, ‘to kill two birds with one stone’, some underwear for the boys.

Wrapping up this new clobber took for ever. The old boy behind the counter meticulously cut off the individual labels, folded each garment carefully onto brown paper, and made little parcels which he tied up with string. Bob and William occupied themselves chatting to him about the state of the war, the torpedoing of a hospital ship on its way to Brest two days before, and their own imminent departure on Sunday. This was too much for Clara, so she went and sat on a chair by the entrance: the chair for weary or aged customers. Mary stood by her side, silently eyeing up the business going on at the counter. The clerk’s dandruff had showered his well-worn three-piece suit; his long fingernails were grubby from ink and string. Her first new clothes. No one’s else’s hand-me-downs any more.

Clara twittered, ‘I wish they would get a move on, I’m more than peckish now. How you doing, Mary? Starving, I’m sure. We are going to have to fatten you up, young lady.’

Mary ‘mmm’-ed in agreement, through tightly clamped lips. She was staring at the backs of the two brothers. They didn’t look like brothers. Where Bob was dark, delicately built, handsome, and open-faced, William was thick-set, taller, with light, colourless hair and dull yellowy skin. He didn’t have Bob’s aquiline nose, high cheekbones, and square lips; he was not handsome at all. William was hidden in his skin. There was no light shining from him, everything was pasted down. Bob looked like his mother. Mary decided that William must take after the dead father. She eagle-eyed the payment. The brothers shared the cost. Replicas of what she had seen in the sideboard yesterday emerged from both their pockets. They counted the money out and handed it to the scurf-laden old clerk, who placed it into a tin canister along with their bill.

She watched the tin bullet fly along wires above the counter to the payment cubicle at the end of the store. A hawk-nosed spinster with a severe middle parting tallied everything up and sent the change flying back to the clerk.

‘Slow down, Mary, no one’s going to pinch it. At least try and taste it before you swallow it.’ Bob grabbed her wrist and winked. She winked back.

Mary had almost polished off her double pie and mash, swimming in delicious green liquor, before the rest of them had even got going. Clara didn’t care for the secret ingredients of the pies and had gone for her usual, jellied eels, from which she was delicately picking the bones. Mary wanted the eels as well, but knew the pies would fill her stomach for longer.

‘Sorry. Am I showing you up? I’ve never been looked after like this before, it’s made me starving hungry.’ Mary studied all three of them.

‘You’re hungry because you’re carrying,’ said Clara. She said it in such a way that Mary couldn’t fathom which way it was intended. It wasn’t whispered or declared with any attitude, just said – as if the dustcart or the milkman had arrived, and Clara carried on filleting her food.

Mary knew she would have to keep her wits about her if she was ever going to translate the whys and wherefores of Clara’s and William’s thoughts.

Clara took her time, still eating long after the other three had well finished. The pie shop was getting very busy and the counter queue now stretched into the street. Some people were taking their food away with them, the rest squeezing themselves into any spaces left at the long tables, giving miserable grunts to anyone still taking up a seat after they had finished their food. Which, of course, meant Mary, William, and Bob. Mary was dying for a smoke and gestured at Bob, putting two closed fingers to her mouth and gently inhaling. He gave a shake of his head. Outside, while they waited for the tram, he whispered to her that it looked common for women to smoke in public, and he didn’t want to aggravate his mother and brother. She laughed. Clara and William gave her a sharp look and shuffled their feet into different arangements.

‘Fuck me, maybe even laughing makes a girl look common around this lot,’ thought Mary.

Bob put his arm around her shoulder and whispered to her again, ‘Soon as we’re back indoors, I’ll roll you one. Promise.’

Bob paid their fares this time, and Clara spent the journey talking about what they would have for their tea.

‘If it’s all right with you, Mary, I thought we’d have the leftover stew as soup with some bread and dripping; the lamb’s all finished.’ This was said as if there were some choice in the matter, yet delivered as a foregone conclusion. Not that Mary felt the need for a choice; she was getting to grips with the luxury of having two bellyfuls in one day.

She got her smoke. Bob lit the fire in the parlour, William made a pot of tea, and Clara went for a lie-down on her bed. Mary felt a bit at sixes and sevens. This domestic palaver was confusing her: she didn’t quite know how to help, or when. Sweet William finished his tea, picked up the newspaper, and retired to the outside lavatory. At last they were on their own.

‘Bob, you do all like me, don’t you? I mean, I would help more, but I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. How do you think it’s going to work out? Me being here on my own with your mum?’

Bob picked her up and plonked her on his lap. He squeezed her as tight as he could, kissed her forehead, kissed her chin, her nose, and then her mouth. She snuggled into him and wondered if she could have told him what was on her mind in a clearer fashion. She wasn’t that sure herself what it was that she needed to know.

‘Mum will show you the ropes. Don’t worry. You can’t learn what to do all in one day, can you? By the time I’m back home you’ll be doing all right. Why don’t you start by putting on one of your new frocks, and chuck those bloody old boots away. Come on, let’s see you looking all fancy pants.’

But she couldn’t. The packages were in the bedroom and she didn’t want to disturb Clara.

‘I’ll start my fancy-pants life tomorrow. I’ll get all togged up for you then.’

Tomorrow would be Saturday, their last day together. On Sunday morning at the crack, Bob and William would be off for at least six months. Mary took it for granted they would return fine and dandy. The war hadn’t filtered through to her much, it was simply another aggravation to put up with. For most of the time she forgot about it.

After soup and dripping, the four of them sat round the fire, occasionally chipping in bits of conversation. Mostly it was quiet. Clara sat in one armchair darning socks, William in the opposite one knitting something grey and chunky on big fat needles. Bob and Mary were doing a wooden jigsaw puzzle of an old sailing ship on the dining table by the window. Every time one of them managed to put a piece in its right place they would tap twice on the table. ‘Dah, dah!’

Bob was better at it than Mary. He knew all about ships, from one end to the other, and was concentrating. Mary was concentrating on other things. Her mind was on tomorrow, and the next day, and the next. It was draughty by the window and she wanted to get into that bed again, to be asleep before Clara came in. She was full of food and thoughts and needed to be on her own for a while.

Tomorrow morning she was going to be shown the local shops. In new frock and boots.

A spindly box shrub struggled to grow behind the low brick wall that led up the path to the front door. Number fifty was in the middle of the terrace of identical yellowy brick houses. They each had a large protruding bay window on the ground floor and two arched windows above. The windows and doors of every house had been painted in the same high-gloss brown. Clara was very proud of the fact that her windows stood out from the others. She had heavy wooden venetian blinds to protect the full-length lace curtains behind. The other houses only had lace curtains in the bottom halves of the windows, to keep out passing nosy parkers.

These streets of terraces fanned out to the high road with its small cluster of shops, a ten-minute walk away. The butcher, the baker, the greengrocer, the cobbler, the public steam laundry, the pawnbroker, and, above the pawnbroker, the herbalist. The milkman with his horse-drawn cart came very early each morning. The horse was called Plimsoll because, like a slave, he had been named after his boss, Stanley Plimsoll. Both horse and man had bad teeth, bad breath, and a bad temper. Clara took Mary into every shop – even the pawnbroker’s, to climb the stairs to the herbalist above, where a paper screw of senna pods was purchased. Next stop was the cobbler’s, to have William’s and Bob’s shoes repaired while they were away, and then on to the butcher, the baker, and the greengrocer’s. This last supper was going to be as special as wartime conditions would allow, aided and abetted by little extras from the shopkeepers. Steamed meat pudding, carrots, and turnips, followed by bread pudding.

Boxing Day 1956

We were all wearing our overcoats to keep warm. ‘This is a bitter Christmas,’ Mum had said yesterday.

Marching from the front room into the bedroom, then back out into the passage, Nanny and Granddad were attacking each other with vicious words. I think my mum was trying to keep out of their way. She was in the scullery making tea and toast for anyone who could face breakfast after the night before, trying to keep my baby brother quiet at the same time. My newish dad was out there with her, splashing about, having a shave before someone else commandeered the sink.

I crawled into the sideboard to get away from the noise, the cold, and the horrible stink. Granddad’s final performance before he had gone to bed was to spew up in the fireplace. The smell of beery sick from the grate mingled with the burning of white crusty bread floating down the passage from the scullery. My cousin, Pattie, was given the gut-tugging job of cleaning out the grate and getting the fire going, sharpish. I should have been giving her a hand, twisting old newspapers into plaits thick enough to work as kindling, or bringing in more coal from the scary outside coal-hole opposite the front door. Instead, I stayed in my sideboard, lying on the plastic-wrapped sheets that Nanny hadn’t managed to peddle before Christmas – she’d been relying on the money, that’s what I’d heard her tell my mum.

‘What are you doing in there? They won’t be in there, you silly little cow.’ Nanny dragged me out and closed the door on her tallyman secrets. She gave me a wink and a ‘shush’ with a finger to her mouth.

Pattie was going to get into trouble as well, because she was taking so long to make the fire, using newspaper to protect her hands from Granddad’s throw-up and trying to hold her nose at the same time.

‘For Christ’s sake, it’s not going to bite you; uglier things than that have married your mother. Now get a move on, we need to get the babies fed and watered,’ Nanny shouted at her.

Pattie jumped out of her skin, hitting her head on the mantelshelf. And there they were, sitting in the middle of Nanny’s frayed, rose-patterned carpet, surrounded by crumbs of last night’s fire. Nanny spotted them straight away and laughed and shouted out at the same time. ‘Oi, you lot, we’ve found them. You’ll never in your pip believe where.’

Mum came running in with Buster on her hip and the grill pan in her hand. My dad followed her, half his face covered in shaving soap. I crawled back into the sideboard and peered out. Sooty lumplets of burnt coal and blackened strips of newspaper had been chucked across the floor. It was as if a chopped-off head had been burnt to ashes, the skin, bone, eyes, and mouth crushed to powder. Only the teeth were left. Teeth, I knew, were very difficult to get rid of, because the police were always searching for murdered people’s dental records. The top set snarled up at us from the carpet, the lower set looking lonely and scared near the window.

Granddad’s false teeth had been found at last.

‘A quick brush-up and a soak in bleach for an hour and they’ll be as right as rain,’ Nanny said, as she picked them up and went off to the scullery.

Granddad’s face would stop looking like an empty envelope and he would be able to chew his Boxing Day Feast properly along with the rest of us.

Well almost all of us.

CHAPTER THREE

Mary

The stove was in, the sink was in. Mary was in. William’s bed and chest of drawers were out, downstairs in Clara’s bedroom.

That last Sunday morning had seen clinging squeezes and tears between Clara, William, and Bob. They read each other’s eyes for a sign that they would see each other again. It was the same at every leaving; they would never get used to it. But Mary’s imagination was more stunted: she couldn’t think beyond a day at a time. She heard him say he would write to her, send her money, be back in a few months. Hopefully before the baby was born. Then they would get married. That’s what she heard, so that’s what she accepted.

Bob was grateful for Mary’s innocence, that she didn’t make a fuss, and with a hug and a wave he and William strutted down the street back to some bastard’s war.

It didn’t take long to dawn on Clara that Mary had to be house-trained. How to shop, how to cook, how to clean.

Mary would never fall in love with hygiene or housework. All this constant washing and ironing, washing up after every meal, after every cup of tea, was such a waste of time. In the months that Bob was away Clara taught her all his favourites. Mary learnt how to make meat pudding, rice pudding, and of course, bread pudding. She was turning into a little pudding herself, the only giveaway that she was pregnant.

Pregnancy hadn’t brought any new fancies or changes of mood. She was waiting to deliver a parcel, that was that.

In that first month that Bob had gone, she hadn’t touched a halfpenny of the big white five-pound note he had given her. It was for emergencies, he’d said, and, nearer the time, to buy the necessary bits for the baby. The money never left her. At night it went under her pillow and during the day she walked around on it, in one of her boots. The bundle of fivers in the sideboard drawer had long disappeared. It was one of the first things she had checked out. She decided it must have been used up that day at Boardman’s. Clara held the purse strings, and if Mary needed anything she had to ask her for it. A few pennies for tobacco always came with a lecture, which was getting on her nerves. That five-pound note would have to be broken into.

Mary wanted the moment; she couldn’t afford the future. All her life she could deal only with the moment.

Bob had never stopped thinking about her and wrote as often as the mail and the war allowed. Mary had almost forgotten what he looked like, sounded like, or even who he was any more. There was no point in writing back, he could be anywhere.

The moment the pregnancy started to show, she made another dent in the fiver and treated herself to a cheap wedding band. By June, her breasts and seven-months-gone stomach were pushing hard at the seams of her frock. The neighbours knew she wasn’t married yet but turned a blind eye for Clara’s sake.

Mary’s playtime came during Clara’s regular-as-clockwork afternoon snooze. On bad weather days she would poke around the house, trying to find any secrets lurking there; on good weather days she would stroll through the park or to the shops, and occasionally hop on a tram.

How Mary got away with it she never knew. She had walked right past them before the penny dropped. That old familiar sound. The cross fertilization of two tutti-frutti planets. It was her big brother Patrick, strolling along with four other navvies, filthy dirty and laughing their heads off. It was his laughter, the way he tossed his head back, that had made him miss the sight of her, his little sister, very pregnant and looking like she had come up a few inches in the world. She heard the men stop and in that instant she was round the next corner crouching in someone’s front porch. The burden of the baby made her legs and back hurt. It was time for a sit down and a smoke. ‘At least eight more fucking weeks of this,’ Mary moaned to herself.

She shouldn’t have come here today. What was he doing in Stratford anyway? If the Burkes ever found her, she would lose everything. Like locusts, they would nibble every penny away, then they would start on Clara, Bob, and William until every one of them went down the sewer. She knew all their tricks; they had educated her well. Bob wouldn’t stand a chance against them.

‘You’re as white as a sheet, Mary. What’s happened? You all right?’ Clara was up and busy ironing by the time Mary got back home.

‘Yeah, yeah, I’m just a bit tired. I’m going to have a little kip, if you don’t mind, Clara.’ Mary puffed her way up to her quarters and couldn’t wait to flop down on the irresistible pillows, linen sheets, and blankets. She would shroud herself in good linen for the rest of her life.

The next day Clara took Mary to the herbalist’s to let him give her the once-over and check that everything was as it should be. A tonic was prescribed, or, as Mary called it, her ‘bottle of jollop’. For the next weeks she didn’t stray very far; she was too big to be seen in public now. To display a body that had obviously seen sexual action wasn’t decent.

Eventually a slow daughter crawled out of Mary in the middle of the night, at the beginning of September 1918. Mary named her Florence Maud, after no one in particular: baby Flo.

Three days before Christmas 1918, Bob and William came back home safe and sound. They peered at the three-month-old bundle, ‘umm’-ed and ‘ah’-ed, asked if she was always that quiet, and plonked a red fez on her head. The hat fell over the baby’s face and down to her neck. Three-month-old Flo tilted her head to one side and stayed very still. She didn’t cry or panic, but simply let it all happen – a bird in a cage with its cover on for the night.

The wedding would get done in the new year. In the meantime, Clara was so bewitched with her boys being home that she allowed Bob and Mary to live upstairs as man and wife immediately. Their single bed would be replaced with a double after the wedding. She didn’t want them to be too comfortable, too soon.

They were all going to have a grand Christmas.

William accepted his new arrangements, sleeping downstairs in his mother’s room, with good grace. He didn’t think it would be for long.

The wedding finally took place at St Luke’s Church, West Ham, in March 1919. They left their seven-month-old daughter outside in her pram. The whole performance didn’t take long. There was no delicate trawl down the aisle, more a quick trot to get it over and done with. The handful of witnesses consisted of Mary’s future mother-in-law, future brother-in-law, two of Bob’s schoolmates, and the vicar. No other Burke in evidence. She thought of letting her family know that she had come up in the world, but never got round to it. No point in sending them a letter either, because Mr and Mrs Burke and the rest of their tribe had never learned to read and write. That had always been Mary’s job. And her special gift.

Boxing Day 1956

‘Win, me and your dad are getting out of your way. Tell Len when he gets here that we’re in the Red Lion,’ my dad shouted upstairs. Mum heard him but couldn’t be bothered to answer over the din. She was upstairs changing my brother Lionel, who was crying. He was exactly three months and one day old – his first Christmas on this earth. Jumping and hollering with them was my other brother, Buster Bill.

Buster Bill from Shooter’s Hill. I don’t know where that came from; we never had anything to do with Shooter’s Hill, we just used to sing it to him when he was being good.

He was two years old and ‘a fucking genius’, my dad told everyone.

Nanny was in the passage, telling them not to come back pissed if they didn’t want their dinner chucked over their bonces.

‘Mary, you’re all woman, you are,’ Dad said to her.

A spanking on the door knocker made more commotion. I slid into the passage and saw that it was Aunt Doll and Uncle Len, with my cousins, Ron and Barbara.

‘Perfect timing mate. Me and Bob are just off down the pub. Keep your coat on and turn round. Hiya, Doll, see you later.’ Dad gave her a quick peck on her cheek, ruffled the heads of Barbara and Ron, and pushed Uncle Len and Granddad out of the door.

Aunt Doll stared at Granddad’s sunken face. ‘You’re not going out like that, Dad, are you?’ she said. ‘Put your teeth in, for Christ’s sake.’

‘He can’t, the silly old bastard. We’ve had a right performance here this morning,’ Nanny shouted as she walked down the passage.

The door slammed and the men were out and free for a few hours.

‘Kids, go in the front room and keep warm. Behave yourselves or you’ll have me to answer to. Follow me, Doll, I’ve got to get this joint in, else we’ll never get any grub.’ Six-year-old Barbara and eleven-year-old Ron did as they were told. I was still half in the room and half out in the passage, and Aunt Doll gave me a peck on the cheek.

‘Where is everybody?’, she said as she poked her nose into the front room and then carried on towards the scullery.

I nodded my hellos to Barbara and Ron, and said I’d be back in a minute. I could hear Barbara moaning already about how cold it was.

‘Win’s upstairs, seeing to her two. I’ve not heard a peep out of our Carol and the Galoot. They must still be soundo. I don’t reckon they’ve had much kip either. Her kids have been cantankerous all night, and that woke up Win’s boys. To tell you the truth, I was grateful to be down here away from it all.’ Nanny unwrapped a large leg of lamb from its bloodied newspaper as she rattled on. I hoped she was going to wash it before putting it in the oven, and from the look on Aunt Doll’s face she was thinking the same thing. It had been living in its newspaper outside the back door for two days in a wooden-framed box with a chicken-wire door. It was frozen stiff. Nanny lit the oven, took out her big baking tin, and put it on the bath.

Granddad had put the bath in himself. It was opposite the stove, under the window that looked out onto the backyard. The taps didn’t work. The bath was covered in a seen-much-better-days white sheet, and on top of that he had made a worktop out of an old door. King Edward potatoes, Brussels sprouts, and parsnips were spread out, ready and waiting for peeling. The worktop was so low it was going to turn whoever got that job into a hunchback.

‘Mum, give it here. I’ll wash the meat and you can start peeling.’

‘Fuck off, I’m leaving that job for our Flo when she finally decides to make an appearance. She had one of her turns last night and it’s taken the wind out of her sails. But she’s not staying in bed all day, that’s for sure, I’ve got too much to do,’ Nanny clacked as she took the glass with Granddad’s teeth out of Aunt Doll’s way, and lit herself a Wild Woodbine.

From the third step of the stairs I could see everything, and I could press myself into the wall. Aunt Doll had put the leg of lamb in the sink on a plate and was trying to clean off the frozen blood with the ice-cold water as carefully as she could, so as not to get her light grey, woollen duster coat spattered.

‘That’s a lovely coat, Doll. How much was that?’ asked Nanny, puffing away and staring at the coat.

‘It was a treat from our Len. I never asked. If he sees me doing this in it he’ll go spare.’ Aunt Doll concentrated on cleaning the meat and avoided Nanny’s eyes. Money talk was dangerous talk, that’s what Mum always said.

‘No, it’s just that I could probably have got you one. I might have saved him a few bob. Where did he get it from, do you know? I’m sure my tallyman had something very similar.’ All this was interrupted by me nearly being knocked off my perch and Nanny getting a headbutt in the legs from Buster. Mum followed behind, breastfeeding Lionel.