Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

William Paulet is the exemplar of the successful Tudor courtier. For an astonishing 46 years he served at the courts of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth and was one of the men responsible for introducing changes in religious, economic and social issues which shaped England as we know it today. He was a judge at the trials of Fisher and More and a central figure in the intrigues of the succession crisis following Edward VI's reign. Though born a commoner, by his death he was the senior peer in England and, as Lord High Treasurer, held one of the most influential positions at court. Paulet survived a bloody half-century of Tudor politics by making himself indispensable, satisfying the demands of four very different monarchs, while still maintaining his own principles. He watched former friends go to the block whilst he weathered the storms of a changing England. Bringing together the separate strands of biographical study and social history, this book offers a fascinating insight not only into Paulet's long and varied career within the royal household and in government but also, through the innovative use of descriptive scenes, into the many routines and rituals that shaped the everyday life of a Tudor courtier. In Tudor Survivor, Margaret Scard paints a captivating portrait of a great man who for many years held the purse strings of England, and both witnessed and was instrumental in the greatest events of the period. From the Siege of Boulogne to the execution of two queens, the Reformation and the beginnings of Elizabeth's Golden Age, Paulet was there, and the story of his fascinating life reveals the nature of life at the Tudor court set against the politics of the age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 503

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TUDOR SURVIVOR

TUDOR SURVIVOR

THE LIFE & TIMES OF

WILLIAM PAULET

MARGARET SCARD

Frontispiece: Henry VIII and the Privy Council, by an unknown artist.(©National Portrait Gallery, London)

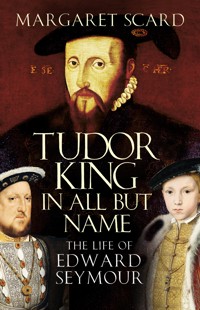

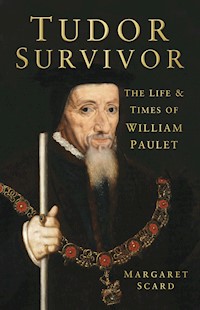

Front of jacket: William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester, unknown artist, detail NPG 65. (©National Portrait Gallery, London)

Back of jacket: ‘The Family of Henry VIII: An Allegory of the Tudor Succession’, detail, c.1572, attributed to Flemish artist Lucas de Heere (1534—1584). The panel is now at Sudeley Castle. To the left are Philip II of Spain and Mary. Edward kneels at Henry’s feet. Elizabeth on his right holds the hand of Peace. According to the inscription the painting was a gift from Elizabeth to Francis Walsingham. (Bridgeman Art Library)

First published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Margaret Scard, 2011

The right of Margaret Scard, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6925 6

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6926 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Preface

Chronology of the Life of William Paulet and Wider Events

1 The Early Years

2 Growing Influence in Hampshire

3 Master of the King’s Wards and the Royal Divorce

4 Comptroller of the King’s Household and the Act of Supremacy

5 The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the Pilgrimage of Grace

6 Treasurer of the Household and the Fall of Cromwell

7 Privy Councillor and Lord Chamberlain

8 The Siege of Boulogne and Lord Great Master

9 Lord Keeper of the Great Seal and the Fall of the Seymours

10 Lord High Treasurer and Marquis of Winchester

11 The Death of Edward and the Disputed Succession

12 Matters of Finance and the Return of Catholicism

13 The King of Spain and War with France

14 A New Queen and the Restructuring of the Exchequer

15 An Oak, not a Willow

Paulet Family c.1340–1572

Notes

Bibliography

Preface

The story of William Paulet, 1st Marquis of Winchester, is an extraordinary account of political survival during the turbulent years of the Tudor dynasty. Born into a gentry family, probably in 1484 as the Wars of the Roses came to an end, Paulet served under four Tudor monarchs, rising to the position of Lord Treasurer and becoming the most senior peer in the realm by his death in 1572. With his long and varied career at the heart of the Tudor court, Paulet serves as the archetype for the successful courtier.

This biography sets out not only to describe the life of William Paulet set against the politics of the time but also to explain his role at court and to look in detail at how he lived. The book includes several short, descriptive accounts of daily life at both home and court – all based on detailed research – that are intended to throw light on the many routines and rituals that shaped everyday life during this period. Covering such events as christenings and funerals, together with descriptions of activities such as dressing and dining, this study hopes to provide a vivid picture of the life of a Tudor courtier.

William Paulet has been a part of my life for many years and this book only came to fruition with the help of many people. However, I would like to express my especial thanks to my husband, Geoffrey, and to Valery Rose for their many hours of proof reading and for their invaluable comments and encouragement.

CHRONOLOGY

of

the Lifeof William Paulet

of

Wider Events

1484

6 June

Probable date of birth

1485

Henry VII defeats Richard III to become King of England

1509

Married Elizabeth Capel

1509

April

Accession of Henry VIIIHenry marries Catherine of Aragon

1511/1518/1522

Sheriff of Hampshire

1514

First appointment as Justice of the Peace

1516

18 February

Birth of Princess Mary

1523

Knighted

1525

Death of Sir John Paulet

1526

5 February

King’s Councillor for law

3 November

Joint Master of the King’s Wards

1529

3 November

Member of Parliament

1530

Death of Cardinal Wolsey

1531

January

Surveyor General of all possessions in the King’s hands by the minority of heirs, also Surveyor of the King’s widows and Governor of all idiots and naturals in the King’s hands

1532

May

Comptroller of the Royal Household

October

Member of King’s entourage to France

1533

Joint Master of the King’s Woods Surveyor of Woods in the Duchy of Lancaster

June

Travelled to France with the Duke of Norfolk

1533

25 January

Henry marries Anne Boleyn

April

Act in Restraint of Appeals

May

Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon declared invalid Marriage of Henry and Anne Boleyn pronounced legal

7 September

Birth of Princess Elizabeth

1534

Act of SuccessionAct of Supremacy

1535

1 July

One of the judges to try Sir Thomas More

1535

6 July

Execution of Sir Thomas More

1536

12 May

One of the judges to try men accused of consorting with Anne Boleyn

October

Organising supplies for King’s army during Pilgrimage of Grace

1536

7 January

Death of Catherine of Aragon

19 May

Execution of Anne Boleyn

30 May

Henry marries Jane Seymour

October

Pilgrimage of Grace

1537

Sole Master of the King’s Wards

October

Treasurer of the Royal Household

1537

12 October

Birth of Prince Edward

24 October

Death of Jane Seymour 8

1539

9 March

Created Baron St John

1540

July

Master of the Court of Wards

1540

6 January

Henry marries Anne of Cleves

13 July

Annulment of Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves

28 July

Execution of Thomas Cromwell Henry marries Catherine Howard

1541

Master of the King’s Woods

December

One of the judges to try Thomas Culpeper and Francis Dereham

1542

Master of the Court of Wards and Liveries

19 November

Privy Councillor

1542

13 February

Execution of Catherine Howard

1543

6 May

Installed Knight of the Garter

16 May

Lord Chamberlain of the Royal Household

1543

12 July

Henry marries Catherine Parr

1544

Organising supplies for King’s army during Boulogne campaign

1544

War with France and the capture of Boulogne

1545

Governor of Portsmouth

November

Lord Great Master of the King’s HouseholdLord President of the King’s Council

1545

French invasion threat and sinking of the

Mary Rose

1547

January

Executor of Henry VIII’s will

March–October

Lord Keeper of the Great Seal

1547

28 January

Death of Henry VIIIAccession of Edward VI

1549

October

Involved in the overthrow of the Duke of Somerset

1549

First Edwardian Book of Common Prayer Rebellion in west and east of England

October

Coup against Duke of Somerset

1550

19 January

Created Earl of Wiltshire

3 February

Lord High Treasurer

1551

11 October

Created Marquis of Winchester

1 December

Lord High Steward at the trial of the Duke of Somerset

1552

January

Duke of Somerset executed Second Edwardian Book of Common Prayer

1553

6 July

Death of Edward VI

10–19 July

Lady Jane Grey proclaimed Queen of EnglandAccession of Queen Mary IRepeal of Edwardian religious acts

1554

25 July

Witnessed marriage of Mary I to Philip of Spain

1554

January/February

Wyatt’s Rebellion

November

Parliament agrees to the restoration of Papal authority in England

1558

25 December

Death of Paulet’s wife, Elizabeth

1558

17 November

Death of Mary IAccession of Elizabeth I

1559

Act of Uniformity

April

Elizabeth declared Supreme Governor of the Church in England

1561

4 June

Fire at St Paul’s Cathedral

1562

October

Elizabeth nearly dies of smallpox

1566

5–25 October

Speaker in the House of Lords

1566

Parliament asks the Queen to name a successor

1572

10 March

Death of William Paulet

1

The Early years

The long procession moved slowly along the track towards the distant church tower. Above the banks on either side the first blackthorn blossom heralded the approach of spring and early primrose flowers nestled amongst the clumps of grass. The sun was shining but the earth was hard from recent frosts and the ice on the puddles in the cart ruts splintered beneath the walkers’ feet. At the front of the procession thirty poor men, dressed in black gowns and walking two by two, were followed by a singing choir and priests, while stretching away into the distance behind them came a long line of over 100 knights, gentlemen and esquires all attired in black and riding two abreast. One rider held aloft an embroidered standard that fluttered overhead displaying the motto ‘Love Loyalty’ with a crest of a golden falcon, its wings outstretched and with a ducal coronet around its neck. Completing this first part of the procession rode three men, each carrying a white stick, the symbol of their offices as Comptroller, Treasurer and Steward in a great house.

The heart of the procession was led by five men riding on horses caparisoned with black cloth. The leader carried a large banner displaying a coat of arms of three black swords, points downwards and with gold hilts, set within an ermine border. The other four riders, all heralds, wore tabards embroidered with coats of arms and amongst them they carried a helmet and crest, a coat of arms, a sword and a shield. These men preceded an oak coffin draped in a black pall and carried aloft by pallbearers. It was a third of a mile to the village church from the palatial house where the procession had begun, too far for the six men who bore the coffin but they were accompanied by another six to take their places. Beside the coffin walked four men holding banners displaying the ancestral marriage alliances of the deceased and following behind rode the four sons of the dead man with other male relations and friends. Above the distant toll of the church bells they could just hear the sound of the choir of men and priests whose soft chanting drifted back to them and to the many knights, esquires and yeomen who walked at the rear of the procession. It was apparent to any onlooker that this funeral cortège was for a man of great importance.

As they approached the church some of the mourners talked of the life of the deceased. There was disagreement about his age. Some believed he was 87 while others said he was older, more than 100 – but all agreed that he was ancient. They spoke of his remarkable achievements, of how, born the son of a country gentleman, he died as the foremost noble in England, next in rank to Queen Elizabeth herself. They recounted how he had begun his career in royal service during the reign of the Queen’s father, Henry VIII, and had maintained his place at Court to serve under three more monarchs – Edward VI, Mary and eventually Elizabeth. His contemporaries were all dead and he was the last of the men who had advised Henry VIII during the great events of that reign. The mourners marvelled that he had managed to survive the dangers of Court life, the factional struggles of ambitious men and the ever-changing religious demands of each monarch. Like a sturdy oak, William Paulet had weathered all the storms of Tudor rule.1

The family background and upbringing of William Paulet, 1st Marquis of Winchester, were not extraordinary and did not mark him out for a brilliant career. Paulet inherited a family name that can be traced back to the reign of Henry II in the second half of the twelfth century. Hercules, Lord of Tournon in Picardy, had accompanied the King’s third son, Geoffrey, to England and was granted land at Powlett in Somerset. Following the custom of the time he assumed the name of the place where he settled and became Hercules de Powlett. By the sixteenth century the most common usage was Paulet. Although Paulet’s ancestors did not hold influential positions at Court they did manage to consolidate their position as gentry, largely by the acquisition of property through financially beneficial marriages. The first of these took place around 1320 between Sir John Powlett, sixth in descent from Hercules, and Elizabeth Reyney who inherited her father’s considerable fortune. Sir John’s grandson, William, brought further land into the family with his marriage to Eleanor de la Mare, who was heiress to her father’s property at Nunney Castle in Somerset and Fisherton de la Mare in Wiltshire. Later their son, Sir John, inherited his father’s properties in Somerset and Wiltshire together with those of his mother, and then substantially increased his fortune in 1427 by his marriage to Constance, the grand-daughter and co-heiress to Thomas Poynings, Lord St John of Basing.2

Sir John Powlett and Constance Poynings were the great-grandparents of William Paulet, the future marquis. When their son John died in 1492 William’s father, another Sir John, inherited an extensive portfolio of lands and property, which included his principal estate at Basing in north Hampshire, the manor of Fisherton de la Mare and several other manors in Hampshire, Wiltshire and Somerset. Sir John served as one of the King’s army commanders at Blackheath in 1497, when the Cornish rebels were subdued, and in 1501 he was created a Knight of the Bath on the occasion of the marriage of Prince Arthur to Catherine of Aragon. He married his cousin, Alice, the daughter of Sir William Powlett of Hinton St George in Somerset, a family connection that was strengthened when his sister Margaret married Alice’s brother Amias.3 Sir John and Alice had six children – four sons, William (the future 1st Marquis of Winchester), Thomas, George and Richard, and two daughters, Eleanor and Catherine. While William was rising to prominence at Court his siblings appear to have led ordinary lives. Only his brother George features briefly in William’s story in an incident that resulted in George spending a short time in the Tower.

Revered as he was for his longevity, establishing the exact year of William Paulet’s birth is almost impossible. Suggested dates of birth have been 1465, 1473, 1474, 1483 and 1484, meaning that Paulet could have been as much as 107 years old when he died.4 Prior to the middle of the sixteenth century written records of place and date of birth are very sparse and the only available documented evidence suggests 1484. An inquisition post mortem (an inquiry to establish legal rights over land after a death) in January 1525 described Paulet as 40 years and more, placing his birth at 1484 or earlier.5 This date accords well with his grandfather’s birth in 1428, his father’s birth sometime before 1460 and his marriage by 1509.6 The only record of Paulet’s place of birth (and the day) is found in a poem written as an encomium on the man’s life and death. This tells us that ‘At Fisherton, hight Dalamer, this subject true was borne’ on Whitsun night, which in 1484 fell on 6 June.7 Paulet’s family owned a manor at Fisherton de la Mare in Wiltshire, a hamlet ten miles north-west of Salisbury on the River Wylye. Paulet’s grandfather, John, died in possession of the manor in 1492 and it is entirely feasible that William Paulet’s parents could have been at the manor at the time of his birth and may indeed have used the manor as their home.8Therefore Paulet was at least 87 when he died in March 1572. Any earlier date supposes that Paulet’s father was rather young when his son was born and Paulet rather old when he married.

There is no record of Paulet’s childhood but it is probable that in common with other children of the time he was baptised soon after birth. Due to a high infant mortality rate, many babies were presented for baptism within days of being born because of the belief that only those who were baptised could enter heaven. Members of church congregations were encouraged to memorise the baptism service so they could recite the prayers and baptise a newborn infant who might not survive long enough to be attended by a priest. Godparents were chosen with care to enlarge the family’s social network and to provide opportunities for the future advancement of the child.

For the three days since his birth, the infant had been cocooned within a warm stuffy chamber; now he was being carried by his godmother to his baptism. His two godfathers and his relatives, together with family friends and neighbours, had all come to witness this important event. The only people missing were the baby’s parents who had remained within the manor. They had no part in the ceremony since the godparents would speak on behalf of the child.

The party came to the door of the church and waited until the priest came out to them – before the baby could be taken into the church he must be exorcised of all evil.9The priest asked the name of the child – ‘William’ replied the godparents – and whether he had already been baptised, to which his godmother answered ‘no’. She moved to stand on the right-hand side of the priest (she would have stood upon the left side if the baby was a girl) who began to perform a series of ceremonies to purify the young William Paulet. He made the sign of the cross on the baby’s forehead and breast to free him from the power of Satan. The priest recited prayers over him and then placed a small trace of salt on his tongue. The salt was to be the ‘salvation of body and soul’, purifying his body and driving out the devil. The priest read a passage from the Gospels in Latin, and then those who were able joined him in reciting the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed. After he had made the sign of the cross on the infant’s right hand the priest led the baby with his godmother into the church by that hand while the rest of the party followed behind.10

They gathered around the font where, in answer to questions from the priest, the godparents renounced the devil and affirmed their belief in Christ, and were then admonished that they should ensure that their godchild was brought up to lead a virtuous and Christian life. The priest took the child and after asking the baby’s name again he dipped the child’s head into the cold water in the font. Three times he lowered the baby, each time with the child’s face turned to a different direction, while he recited: ‘William, I baptise you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost’. He raised the child up and passed him back to his godmother then, taking a small jar containing chrism, a mixture of oil and balm, he dipped his finger into the liquid and marked the sign of the cross on the child’s head. William was baptised, he was a member of the Catholic Church and, as a token of his innocence, was wrapped in a white linen chrisom cloth. Finally, taking the lighted candle which stood on the edge of the font, the priest placed it within the child’s open hand before passing it to one of William’s godfathers.11The ceremony was finished and the group thanked the priest and moved out into the sunlight.

The formal part of the day was over and now the christening party could look forward to the feasting and drinking that awaited them back at the manor. William’s father was at the door waiting for them. The three godparents went upstairs to take William to his mother and to congratulate her on the birth of her son. Alice was sitting in bed and took the baby who was starting to fret. She removed the chrisom cloth and cuddled him but when he began to cry she passed him to the wet-nurse who waited by her side. The wet-nurse had been carefully chosen. She came from a good local family and led a clean and sober life, important factors because it was thought that some of her characteristics might flow into the baby during breast feeding. The nurse carried William into her small chamber next door and sat feeding him. When he was old enough to be weaned she would feed him sops of bread soaked in milk or water, perhaps with a little sugar, and when he was teething the leg of a chicken with most of the flesh cut off would serve as a dummy for him to chew upon.12

At last he was finished and she laid him on her bed to change his nappy. She unwrapped the long linen cloth from around his body. The nurse was always careful not to swathe him too tightly. Although the binding would help William to grow with a straight spine and reduced the risk that he might break his legs by kicking too hard, the binding could crush his ribs if too tight and pull his spine out of alignment, leading to a mis-shapen back and shoulders. She removed the wet napkin, replaced it with a clean one and took the swaddling cloth. It was about six inches wide and ten feet long. Starting at William’s shoulders she wound the cloth around his body, wrapping his arms to his side, and down to his feet until he was a neat little bundle, easy to carry – he could even be hung on a hook out of harm’s way.13With his head protruding from the top he resembled an insect emerging from a chrysalis. As the summer weather got hotter she might leave his arms free from the bands, beginning the swaddling at his armpits, so that he was a little cooler. She lifted up the baby and going back to Alice’s room placed the little bundle in the cradle, a decorated wooden box on wooden rockers, and tied strings across the top so that he could not fall out while being rocked.14The godparents were taking their leave of Alice. The merrymaking to celebrate the birth of John Paulet’s first son and heir had begun down below and they were keen to join the other guests.

After six months the swaddling bands were removed from the baby and the young Paulet was dressed in the unisex attire for boys and girls. This comprised full-length bell-shaped skirts or petticoats, with a top possibly styled as a doublet, all worn over a shift. Young children sometimes wore a ‘black pudding’, a narrow padded ring of black silk or satin that was tied horizontally around the head, to protect them in case of a fall.15 At the age of six Paulet was ready to be ‘breeched’, a proud family occasion on which he first wore hose and breeches. From then on he ceased to wear children’s clothes – except perhaps for play when he might have worn a smock over loose trousers – and instead would have worn garments that were smaller versions of men’s clothes. The style during the reign of Henry VII was for linen or flannel drawers under hose similar to tights, with a shirt and a top garment of a doublet, like a close-fitting jacket that reached only to the waist. For extra warmth a gown was added, which could be either short or to the floor. Shoes were flat with a wide, round-toed shape.16

Childhood was short. Children were dressed to look like adults and were encouraged to grow up quickly in a world where infant mortality was high. Young boys were cared for and educated by the women in the household but after a few years they started to move into the world of men. In 1543 the future monarch Prince Edward was moved to his own suite of rooms at Hampton Court at the tender age of six; the women of his household were dismissed and a household of gentlemen and tutors appointed. Children were taught to be well-mannered and polite and to be respectful towards others. It was important to understand who had precedence over whom. The young Paulet would have learned which people were above his parents in society and those who were below.

By the time of Henry VIII’s reign the government of England and the management of the Royal Court employed the services of a decreasing number of clerics and nobles and an increasing number of officials with an academic education. This provided an opportunity for young educated men who might not previously have gained a place at Court to seek a position, usually through a sponsor. To this end the young William Paulet would have been taught all those skills and attributes that were considered essential for a young Tudor gentleman and which would enable him to socialise with and impress those people who were ranked above him in society.

Although some courtiers received little academic education – in 1550 the Imperial ambassador commented that Sir William Herbert, the Master of the Horse, could speak only English and could neither read nor write – Paulet’s impressive administrative skills were only made possible by his good education.17 This would have begun at the age of seven or eight when attendance at school generally commenced. While most girls continued to be educated by their mothers, it was usual for boys to start attending lessons either at home with a tutor or in a school run by a priest or at a grammar school, so-called because its primary purpose was to teach Latin grammar. Latin was an essential part of an ambitious schoolboy’s education. It was the language of church services and of written law and was used by clerks for official documents and accounts. It was even useful as a common conversational language. In 1533 the Imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, during a discussion with several councillors including Paulet was asked to speak in Latin as the councillors did not all understand French.18

Boys’ earlier instruction in social and musical skills continued but was supplemented by the teaching of French, arithmetic, geometry, scripture and handwriting. Much of the teaching was oral and in some subjects the emphasis was on learning by rote. For those at school the day was very long and the boys attended six days a week. The day began at 6am with prayers, and lessons continued until 11am or noon, with a short break for breakfast at around 9am. After a midday meal and recreation, studies resumed and continued until 5 or 6pm.19 Holidays were short but the children usually celebrated the many church festivals and saints’ days with a day off. On St Nicholas’ Day many great churches chose a ‘boy-bishop’ from amongst the choristers to preside over the service and to give a sermon. The local schoolchildren were encouraged to attend this service and one can imagine their delight to see one of their own as ‘chief cleric’. Shrove Tuesday was another holiday when the boys were spared lessons and allowed to spend the day in ball games and cockfighting.20

School resources were sparse and in 1518 John Colet ordered the boys of St Paul’s in London to provide their own candles. Paper was of poor quality and very expensive and so a ‘payre of tabullys’ (or tablets) were more often used for writing on with chalk. Pencils were almost unknown and boys used pens of sharpened goose quills, carried in a small ‘penner’ or sheath, with ink made from oak apples and green vitriol (a mixture of iron sulphate mixed with fish-glue and water). The first Latin grammars were printed in England in 1483 as pamphlets costing one penny or so and some pupils had these to supplement the few books owned by the schools. School regimes were harsh; an early woodcut shows a schoolroom with the pupils sitting on forms and the schoolmaster at a high chair with a cane in his hand.21 Sir Thomas Elyot, in 1531, exhorted parents to choose a good master for their boys because ‘by a cruell and irous maister the wittes of children be bullied’. He desired that they should be encouraged to learn through praise and with ‘such prety gyftes as children delite in’, and was a great advocate of exercise by which ‘the helthe of man is preserved and his strength increased’.22

Between the ages of 14 and 18 the boys might enter university at either Oxford or Cambridge, although some sons of the nobility and gentry were first sent to live and work in the houses of other noblemen. One such was Sir Thomas More, a contemporary of William Paulet, who at the age of twelve was placed as a page in the household of Cardinal Morton for two years. The primary purpose of this was the quest for patronage. It was hoped that the host would act as patron to his charge and, when the time came, endeavour to help him acquire a good position, preferably at Court. In a large household there might be several young men in attendance and, if Paulet did follow this route, he would have found himself in the company of boys from both noble and gentry families. The pages’ chamber at Hampton Court shows how pages lived together in one room, sleeping on straw mattresses, close at hand in case they were needed. The boys continued to receive tutelage in academic subjects while they worked as pages, serving at table and attending to the diners’ needs. Their education included the social skills considered necessary for a gentleman. They learned to show courtesy to women, respect to those above them and politeness to those below. Their instruction included how to care for themselves and how to dress well and make entertaining conversation.

Instructions on good manners and behaviour in company were given in publications such as the Boke of Nurture and The Babees’ Book. From these, young men learnt the rules of social precedence, the complicated rituals which accompanied the preparation of the table before a meal and how they should wait upon their lord. They were instructed not to rush to him but to use smooth actions and gentle words, to offer clean water and towels for him to wash his hands at meals and to stand before him until bidden to sit. When cutting a loaf of bread they were to offer the ‘upper crust’ to their lord – the bottom crust would be dirty from the burning faggots placed in the oven to heat it before baking commenced.

Great emphasis was placed on not offending one’s neighbour at table. Etiquette demanded that you did not ‘claw your head or your back as if you were after a flea, or stroke your hair as if you sought a louse’. Pages were instructed not to ‘pick your nose … sniff … blow it too loud, lest your lord hear’ and neither ‘retch not, nor spit too far’. And there was the rather indelicate advice to ‘alle wey be ware of thy hyndur part from gunnes blastynge’. Because of the communal style of eating, diners were encouraged to ‘keep clear of soiling the cloth’ and not to lean on the table – wise advice for people eating off trestle tables. They were to ‘touch no manner of meat with thy right hand, but with thy left, as is proper’ and to wipe their mouth before drinking from a communal cup.23 There was advice ‘against taking so muckle meat into your mouth but that ye may right well answer when men speak to you’.24 The books also gave very precise instructions concerning the different methods of carving various joints of meat and an aspiring young courtier would have given these special attention. It was considered an honour to be asked to carve the meat at the top table and was the mark of a gentleman to be able to do so properly.

In a large house with many visitors the young aspiring courtier would be able to identify a person’s rank by the clothes he wore. Sumptuary laws prescribed certain levels of dress to create a distinction between the classes; for example, only the King and his family were permitted to wear purple silk. The young page learnt how to address each man properly and where he should be seated at table according to his rank. The seating plan was very rigid and a person would be offended if he was placed in a lower seat than was his right. The most important guests sat at the top table on the righthand side of the host. Other guests were seated in descending order down the ‘legs’ of tables, with the lowest ranking visitor placed at the bottom of the left-hand table. A large salt cellar was often placed in the middle of the table – thus those of lower rank found themselves eating ‘below the salt’, away from the family and important guests. Whether Paulet entered a great household or remained at home, by the age of fourteen he would have learned many of the social skills that would later mark him out as a gentleman at Court.

‘After having studied at the University of Oxford, [Paulet] became a student in Thavies Inn three years; after that in the Temple.’25 Although his name does not appear in the University records it is possible that he was a student there because names of students who did not graduate were not always recorded. To attend university at Oxford or Cambridge prior to studying law in London was not unusual. Sir Thomas More spent two years at Oxford and then moved to an Inn in London without taking his degree.

At Oxford and Cambridge the student was admitted to a college or hall where he would live and study. These were run on the lines of a household where the students lived, ate and studied in a large hall and slept in shared bedrooms. The day was long, beginning with prayers at 5 or 6am which were followed by lectures and debates. Paulet would have spent many hours taking part in ‘disputes’ and discussions, and during the first two years at university much time was devoted to learning the skills of logic and rhetoric. This was essential for prospective lawyers but was also considered necessary training for any ambitious young man. Courtiers were expected to be able to converse and debate on any topic and for men in power the ability or lack thereof to sway others by argument could have momentous outcomes. The universities taught other subjects such as philosophy and theology, Greek, mathematics and astronomy, medicine and law. The law offered was canon and civil law, from which the lawyers became known as ‘civilians’, but for those hoping to work in the service of the King it was advisable to move to London and study common law in the Inns of Court.

Attending an Inn of Court in London was an accepted route to follow for many sons of noble and gentle birth who aspired to be courtiers. The Inns were seen as centres of education in the same way as universities, and students were taught not only English law but history, scripture, music, dancing and other noblemen’s pastimes. Society was becoming more litigious and the Inns attracted students who had no intention of becoming lawyers but who wanted enough knowledge of the law to be able to protect their own property. As today, the Inns of Court were Gray’s, Lincoln, Inner and Middle Temple but there were also about ten Inns of Chancery, one of which was Thavies Inn in Oldbourne (Holborn) where Paulet studied. The Chancery Inns each had about 100 students and here the young student barristers would learn basic law before becoming members of an Inn of Court. They learnt to understand legal procedures and precedents and were instructed in the use of writs and the meaning of statutes. They attended court to hear and see how a case should – or should not be – presented and afterwards discussed the arguments they had heard. Much time was given to debating to allow the students to practise and improve their skills of oratory, which would be so vital should they themselves appear in court. While at Thavies Inn, and later in the Temple, Paulet ‘applied himself so well, Inclined to learned skill, Till Utter Barrister he was, He there continued still’.26 He probably spent three years at Thavies Inn before moving to one of the Inns of Court.27 Here his lifestyle would have been similar to that at Oxford. Each Inn had up to 200 members living together as a community, eating meals and studying in the hall and attending communion in their own chapel.

The training Paulet received in the Temple continued that of the Chancery Inns. Highly practical, it involved committing to memory points of law he had heard in lectures and during argument and discussion. Starting at 8am, the students would gather in the hall to listen to the opinions and judgments of barristers as they argued over legal points, and after supper they took part in the moots. This was the most useful part of Paulet’s training. The moot was a practice court where the senior members – the benchers – of the Inn sat as judges to listen to the students argue a case. Initially the students were known as ‘inner-barristers’ and took part in the proceedings from within the bar, the physical barrier which separates the judges from the rest of the court. When they were deemed sufficiently competent they were called to the bar as ‘utter-barristers’ and allowed to argue points of law standing outside the bar at moots.28 Paulet reached this stage of competence and probably belonged to Inner Temple.

Admissions records are scarce and there is no record of his entry to the Inn but from 1505 to 1507 a ‘Paulet’ is listed as marshal for the Christmas festivities at Inner Temple.29 The marshal was one of three members of the Inn elected to oversee the Christmas festivities that stretched from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Night and included banquets, music and dancing, plays and masques. The marshal seated the company at dinner according to their rank and took part in the ceremonies that accompanied the meals.30 Later, in 1535, Sir William Paulet was responsible for his son Chidiock’s admission to Inner Temple. Chidiock was then no more than eighteen and gained entry for two years on favourable terms, surely on account of his father.31

By his early twenties Paulet was qualified as a barrister and set to embark on a career in law. He had learned the skills necessary for a young gentleman in Tudor society and knew how to be agreeable in company and how to dress and carry himself to make a favourable impression. He came from a respectable family and was well prepared to make his way in the world. It is probable that after his training he continued to live in London and practise at the bar since he was later called as an adviser in law to the King.

Paulet’s connection with London is strengthened by his marriage to Elizabeth, the daughter of Sir William Capel.32 They were married by 1509 though we do not know the exact date of his wedding. It is possible that the marriage took place at the church of St Bartholomew-the-Little at the end of Bartholomew Lane where Sir William Capel and his wife, Margaret, were buried in the chapel he built. Sir William started as an apprentice in London, was knighted in 1482 and served as sheriff, MP for the City and was twice Lord Mayor. He had three children – Giles, Elizabeth and Dorothy.33

As the son of a landed family, it would have been quite usual for Paulet’s marriage to be arranged by his parents. Since he married in London so far from his family home perhaps he selected his own bride. The choice of partner was very important to both families as marriage joined together not only the couple but also their relatives, bringing each the possibility of new contacts and opportunities in their social and business lives. Perhaps most important was the financial situation of the bride, and the discussions concerning her dowry and long-term support could make the marriage agreement seem more like a business proposal. Husbands were advised that ‘when himself is departed, his bounty must be present with her, even after death’.34 Should the husband die first, his wife should have sufficient property to support her for the rest of her life. Often a piece of land was held jointly by the couple and then solely by the wife if her husband died first. We can see an example of this within Paulet’s own family when, in 1468, land was settled upon Paulet’s father to be passed after his death to his wife Alice.35

The bride Elizabeth was wearing a new gown of blue damask and, since she had not been married before, she wore her long hair loose down her back. One of the men went inside the church and soon returned with the priest. Elizabeth moved to stand to the left of her bridegroom – a woman’s correct place beside a man because the Bible told them that Eve had been formed out of a rib in the left side of Adam. William took his bride’s right hand and they exchanged vows: ‘I, William, take thee, Elizabeth, to my wedded wife…’, and then ‘I, Elizabeth, take thee, William, to my wedded husband…’

After the priest had blessed the ring William slipped it onto the thumb of Elizabeth’s right hand as he said the words: ‘In the name of the Father’, then onto her index finger as he continued: ‘And of the Son’, then onto her middle finger ‘And of the Holy Spirit’ and finally onto her fourth finger ‘Amen’. This finger held special significance for it was said that a vein ran from the finger direct to the heart.36Paulet had chosen a gimmal ring made of two rings which interlinked to form one, symbolising the joining together of two people. It was given as a token of love and commitment but it was also a mark of ownership and a statement of the status Elizabeth had now accepted. The couple moved into the empty church after the priest, as the rest of the party followed behind them. Standing at the altar step William and Elizabeth listened as the priest prayed for their future together, that they should be blessed with the joy of children, and they accepted the bread as he administered the nuptial Mass. After a final blessing William turned to his bride and led her to the back of the church. Upon a table were laid out small drinking cups with jugs of hippocras, a spiced and sweetened wine drink. The wine was poured out and passed around and the wedding guests pressed around the newly married couple, drinking to their future health and happiness. The cups were soon empty and the party made its way out of the church. The party walked the short distance to Elizabeth’s family home to continue the celebrations. William’s father-in-law was a wealthy man and would want to impress his guests so a great feast awaited them there.

The marriage was not truly formalised until consummation had taken place and great importance was placed on the ceremonial bedding. The couple was accompanied by the wedding party into the bedchamber where, if the priest was present, he blessed the bed and sprinkled holy water over the newlyweds. Amidst much ribaldry and mirth the couple was helped to prepare and the guests left after having seen them into bed. Written advice was available to help couples enjoy happy and successful marriages. Guidance for men suggested that every good husband should ‘afford his wife allowance of all necessary comforts for this present life; for attire and food, for necessity and delight, that she may live a cheerful and a well contented life with him’.37

William and Elizabeth had eight children. Their dates of birth are unknown but the wills of Elizabeth’s parents indicate that six of them were born before the end of 1516.38 There were four sons – John, Thomas, Chidiock and Giles – and four daughters, Alice, Margaret, Margery and Eleanor. All eight children survived into adulthood and married, and Paulet saw some of his great-grandchildren ‘grown to man’s estate’, so there may be some truth in the assertion that he lived to see 103 of his own descendants.39 John inherited his father’s title of Marquis of Winchester but never achieved the acclaim of his father and only held county appointments. Chidiock was prominent in Hampshire and from 1554 to 1559 he served as Governor of the town and castle of Portsmouth. He was twice elected to Parliament. Giles was chosen to be a playmate of the future King Edward VI. Of the other children’s lives few details are known.

2

Growing Influence in Hampshire

At some date close to Paulet’s wedding his father, Sir John, was taken ill and was unable to run his estates or carry out his duties in Hampshire, and Paulet was summoned home to Basing to take charge. Unsuccessful nominations for him to be sheriff in Hampshire in 1509 and 1510 and many later appointments within the county indicate that he may have spent the next fifteen years or so resident at Basing.40 In his will in 1525 Sir John made a point of expressing his gratitude to William for the diligence and kindness he had shown towards both his parents and his brothers.41 This suggests that he had been looking after the family for some time and it is probable that his father had never fully recovered from his illness and that William continued to remain at Basing attending to his family’s care and the upkeep of his future inheritance.

From 1511 to 1526 Paulet was one of the King’s men in Hampshire. England had no police force and the monarch maintained control of the country through local men appointed to positions of authority. In each county the upholders of law and order were local landowners who were the sheriffs and justices of the peace and, later in the century, the Lords Lieutenant. The King relied on the support and loyalty of these men. In return for the local power and authority gained from their position, they were expected to offer unconditional service to the Crown. They not only maintained the laws of the land but executed the King’s orders, collected his taxes and kept him informed of the state of his kingdom. In the event of any serious disturbance they could be ordered to raise and lead an army to quell an uprising, so they had to be trustworthy. A landowner in control of an army was a potential threat to the King and there was always the risk that an ambitious noble could turn that force against the monarch.

Paulet was appointed as sheriff in Hampshire (Southamptonshire) for terms of one year in 1511, 1518 and 1522.42 The term ‘sheriff’ came from ‘shire reeve’ – an officer who oversaw and kept order in the shire – and the office of sheriff originated during the Middle Ages as the Crown’s fiscal and judicial representative in the counties. His primary roles were concerned with ensuring the local populace obeyed the law and paid their taxes. The sheriff, usually a prominent landowner, was the chief administrative officer in each county and was aided in his duties by an under-sheriff and clerk, and by constables and bailiffs who were the local officials within villages and hundreds of the county. Towns such as Southampton and Portsmouth were self-governing and were controlled by the aldermen and councillors, carrying out the King’s instructions. By the sixteenth century many of the sheriff’s duties with regard to maintaining law and order had been passed over to the justices of the peace but he was still responsible for keeping the King’s peace. He proclaimed the Quarter Sessions, summoned juries and carried out sentences. He presided over county elections and was responsible for the collection of debts due to the Crown, such as revenue from Crown lands in the county and fines at the County Court. He also had the authority to raise a ‘posse comitatus’ – a group of armed men over the age of fifteen whom he could summon to quell any civil unrest. Paulet’s grandfather and father had both been appointed as sheriff before him, and his brother George and son John would follow suit.

During his first appointment as sheriff Paulet was instructed by the Privy Council in May 1512 ‘to review captains, mariners and soldiers at Southampton and elsewhere, to certify number of same and arrest and punish rebels’, prior to the soldiers ‘proceeding to foreign ports’.43 This was the Council’s method of assessing manpower and of ensuring that the force was ready. Paulet would have been provided with the numbers of the available local men by the constables and local landowners. The country had no regular army and all men who owed allegiance to the monarch had a feudal duty to supply a certain number of armed men to fight in time of war. During January 1514 the Earl of Surrey was mustering an army at Portsmouth in preparation for an anticipated attack by the French. The local nobility and gentry received the order to provide men to fight and to gather with their retainers at the port. Most, including Paulet, arrived with ‘good companies’ of 20–100 men but nobles such as Lord Arundel sent 300.44 On that occasion the expected invasion never materialised and Paulet, with the men he had raised from amongst his tenants, was not called upon to fight.

Justices of the peace, or magistrates, were central figures in the government of the counties. The position was held in very high esteem and gave an indication of a gentleman’s social standing. Paulet’s sons, John and Chidiock, also served as justices, which helped to enhance the power and control the Paulet family held in Hampshire. Removal from the post was a social disgrace and the King used this threat to ensure that the magistrates used their local knowledge to further his interests rather than their own. The inclusion of members of the King’s Council as justices outside their own shires ensured that each county had some justices with no local interests to give an impartial view on the King’s behalf.

To qualify for consideration as a magistrate, a landowner or his son had to hold land worth at least £20 per annum. The post was unsalaried as it was considered that the landowning classes had a responsibility to maintain the law in their locality. While many justices were members of the nobility, Henry VIII also appointed knights and squires of country families in order to reduce the power of the nobility. A growing number of lesser country gentry and townsmen were increasing their wealth – either by commercial enterprise or from patronage at Court – and were then able to buy large areas of land in the country, thus making them eligible for the position of magistrate.

John Paulet was a justice of the peace and it is possible that William was initially nominated to replace his father during the latter’s illness. His first appointment in Hampshire was made on 24 January 1514, and he was reappointed on 18 October and twice the following year when he was one of about two dozen magistrates in the county.45 Commissions were renewed annually and men often remained in post for many years. Paulet was also appointed as justice of the peace for Wiltshire and Somerset where he owned further estates, and his training as a lawyer was to prove invaluable for his work. In Hampshire all justices were expected to attend the Quarter Sessions held in Winchester, where citizens accused of serious crimes were tried. These were held at Easter, Midsummer, Michaelmas and Epiphany. At other times Paulet dealt directly with persons accused of minor crimes, either sentencing them to jail, allowing bail or committing them to the next Quarter Session. He had the power to order the arrest of suspects and to examine them, and was able to inquire into charges against the sheriff on matters such as jury corruption. Paulet was dependent on the local officials (the bailiff and the constable) to keep the peace and to bring offenders before him. These men were empowered to arrest vagrants and beggars, attend to the upkeep of the roads and maintain general law and order in their area. They passed information to Paulet and he issued orders to them. Since there were many justices at any time within Hampshire, Paulet would have been particularly responsible for maintaining the law in the parishes closest to his own estates.

Throughout the sixteenth century, government involvement in citizens’ lives grew and the responsibilities of the justices increased as their judicial and administrative duties widened. For instance, in 1531 an act of Parliament made a distinction between the two kinds of poor – those capable but unwilling to work and those too old or sick to work. The new act provided for the former to be whipped and for the latter to be allowed to beg under licence. In 1536 the first Poor Law was passed, which gave justices responsibility for ensuring that each parish employed those capable of working, collected alms for those unable to work and cared for those in need. They were given increased responsibility for the regulation of wages and prices, weights and measures, the holding of fairs and markets, the licensing of alehouses and playhouses, the administering of laws against unlawful gambling, the maintenance of religious observance and the upkeep of the highway.

The senior justice of the peace in each county was nominated as custos rotulorum (the keeper of the shire records) and Paulet may have held this title during his father’s lifetime. The King’s commissions and letters regarding any actions to be carried out within the county were issued by the Privy Council and sent to the custos rotulorum. It was his responsibility to call the justices of the peace together ‘for the execution of the King’s commandments’.46 These commissions were generally enacted for a limited time and carried responsibilities such as collecting subsidies or inquiring into the imparkation, or enclosing, of land in Hampshire. Hampshire, being a southern coastal county, was always at risk of invasion, and commissions were often issued to examine and improve the coastal defences and ensure the maintenance of warning beacons. With the two ports of Portsmouth and Southampton in the county Paulet was also frequently involved in the muster of troops and the manning and provisioning of the ships. He described how ‘many times came commandments to gather men to be conducted to the sea-side to defend the coasts’ and that ‘everie castle and fort were furnished with armure and weapon’.47 Paulet was notified of one commission in the autumn of 1523, concerning the collection of a subsidy in aid of the Duke of Suffolk who was marching with an army towards Paris. England was at war with France but there was no money in the royal coffers to pay for it and the funds for Suffolk’s expedition were raised through taxes. All persons in each county owning £40 and upwards in goods or lands were required to pay, and it was the responsibility of the justices to co-ordinate the collection. The commission document, dated 2 November 1523, lists Paulet as commissioner to collect taxes in three areas – Hampshire, the town of Southampton and the city of Winchester. Here, for the first time, he is styled as Sir William Paulet, although only on the commission for Southampton.48 The title is given again the following April in an account of the money collected for the cost of the French war.49 So it appears that during 1523 the King had knighted Paulet during his father’s lifetime, Sir John’s title not being hereditary. Paulet’s knighthood must have been bestowed for services rendered in Hampshire, which suggests that he had already been brought to the King’s notice.

Paulet had another responsibility in Hampshire, which he held for many years, that of steward of the lands of the bishopric of Winchester. He took on the office before 1516 during the episcopacy of Richard Fox and continued when Thomas Wolsey was confirmed in 1529 following the death of Fox. Winchester was one of the wealthiest sees in England and the revenues from the bishopric lands would have been very welcome to Wolsey, who enjoyed an extravagant lifestyle. As steward, Paulet oversaw the administration of the bishop’s manors and lands, examined the way they were run by the bailiffs, held hundred-courts and attended to any business the bishop had in that area. A letter from Paulet to Wolsey in June 1529 concerned a survey that Paulet was making of the castles, manors and lands in the bishopric, possibly an initial inventory for the new bishop. He referred to there being only a few deer in one park – 500 instead of 1,000 – and suggested that certain hunters and fishermen should be punished as an example. He finished by saying that he would be in Taunton on Monday – a long ride from Hampshire but probably not unusual because the bishopric lands were widely spread.50 The appointment was a part-time one. At Christmas 1541 he was paid £10 for the year and received his travelling expenses. His brother George also received £10 for working as auditor.51 Paulet continued as steward until at least 1541 by which date he was devoting much time and energy to his many roles at Court, and some of his responsibilities as steward must have been assumed by an assistant.

Paulet records that after his father’s death in 1525 the King commanded Wolsey to send for him to come to Richmond where he was appointed, with Sir John Mordante, to the office of Surveyor of the King’s Woods throughout the realm, ‘with such fees and allowances as were necessary for them’.52 Although there is no formal record of these appointments, during 1526 Sir John Mordante was appointed with Roger Wiggyston to be ‘surveyors of woods’ and on 28 February of that year these two men and Paulet were named together in a commission to inquire into the state of some of the King’s manors with particular attention to be given to the condition of the woods and the possible sales of felled timber.53