9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

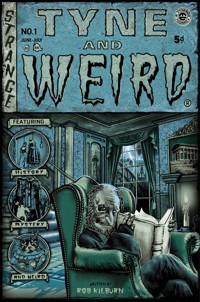

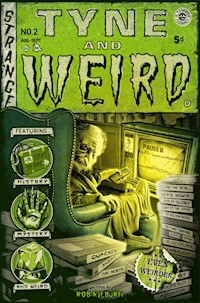

'Stories like this tend to have a life of their own…' From privateers to monkey murderers, kleptomaniacs to automatons and giant bugs to fart lamps – it's time to gather round the fire once again for more tales of North East madness. In this second installment of Tyne and Weird, Rob Kilburn embraces the odd and ventures further than ever into the strange world of Tyne and Wear.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Rob Kilburn, 2022

Illustrations © Dan Underwood

The right of Rob Kilburn to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9219 8

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

This book is dedicated to my son, Oliver Andrew Kilburn.

I dedicate this book to you knowing that though you entered this world at a strange time, you inherited the strength of your mother, Sarah, the creativity of your father and the combined love of us both.

I hope in the years to come you reflect on this strange tome and inherit the curiosity and caution with which it was written.

I also dedicate this book to my little brother, James Kilburn. Not so little anymore but still looking out for his family and brother. I cherish your support and the strength you have given to me and our family.

FOREWORD

1 CROSSING THE LINE

2 WAR

3 BEYOND TYNE AND WEAR

4 THE WEIRD

5 PEOPLE AND PLACES

6 LET ME ENTERTAIN YOU

Greetings travellers!

Welcome once again to the paper embrace of the collection of eclectic tales that is Tyne and Weird.

Going back to my youth, I remember being thirsty for tales tall and small, in particular ones involving the paranormal or themes on the fringe. From urban legends of the customer who finds a fried rat in her fast food, to the friend of a friend who has returned from travelling abroad with strange spots on her lips – only for it to be later revealed that those particular spots can only be acquired from kissing someone who has been in physical contact with dead bodies.

One particular tale I remember hearing that related to the North East was that of a taxi driver who, returning from a fare late one night on a country road, passes a woman looking disheveled and distressed. He pulls over and offers to drive her to safety, though he cannot get much sense from her. During the journey he looks back in the rear-view mirror expecting to see the sobbing woman, only to discover his taxi is empty with no trace of that passenger ever having been there.

Stories like this tend to have a life of their own, being adapted from one person to another having happened to their relative or a friend, and eventually the origin disappears like a mumbled word in a game of Chinese whispers.

The stories included in this book are the very same and will hopefully take on a life of their own upon entering your head. Whether you are telling a friend in the pub or cracking on with a relative at Christmas over dinner, embrace these tales and fulfil their purpose by spreading the word.

If we could all run around doing whatever we wanted, I dread to think of the consequences and the kind of world we would live in. That privilege is reserved for the rich, but the people in these tales, like you and I, cannot live without consequence.

The stories you’ll read in this chapter detail what happens when you cross that legal line, whether right or wrong by modern standards. I ask you, the reader, to put yourself in the shoes of the desperate men and women that committed these crimes.

GRAVE ROBBING AT CHRISTMAS

On Christmas Eve 1823, not everyone was in good spirits. Captain Hedley of Sunderland had a sad task to undertake: the burial of his 10-year-old daughter, Elizabeth.

It was a cold winter and the icy weather in Sunderland parish graveyard had frozen the earth, so much so that the ground could not be properly dug. Unable to penetrate to the usual depth, a shallow grave would have to suffice.

Four sad days passed and the captain wanted to move his daughter’s body to a better part of the graveyard. No doubt this would have been the only thing on his mind for the four days over Christmas, sullying what is the happiest time of the year for most. Determined, he returned to the graveyard only to find that the child’s coffin was bare.

The authorities were alerted immediately and upon investigation they reached the conclusion that the body of his 2-year-old daughter had also been stolen from its tiny coffin.

GRAVE ROBBING AT CHRISTMAS

The authorities were not without suspects, though, and they turned their focus to two strangers who had been seen lurking around the cemetery, particularly at times when funerals were taking place. The police acted quickly and one of the men was apprehended that afternoon.

Word had got out of the foul deed committed by the two strangers and an angry mob soon formed. While being transported to the police courtroom, the baying crowd threatened to stone the man to death. Terrified by the idea that the police may hand him over, he began confessing to the crime.

Constables were sent immediately to the lodgings of the man and it was there they found the criminal’s fellow grave robber, who was in possession of the body of Captain Hedley’s daughter. Packaged in straw, the body was ready for delivery to an address in Edinburgh.

Upon further investigation, the police found human teeth and various documents linking the two men with the removal of six bodies.

It became clear that the fiends had been robbing graves throughout the whole county. The men had been sending the bodies further north by horse and cart to Scottish surgeons. The two criminals would be identified as Thomas Thomson of Dundee and John Weatherley of Renfrew.

The next month, January 1824, the two Scotsmen took the stand at the Durham Sessions, pleading guilty to the offence of grave robbing.

While you might expect such a despicable crime to carry a heavy sentence, the two men received very lenient sentences. For their crimes they received just three months’ imprisonment, together with a fine of sixpence.

HUNG, DRAWN AND QUARTERED

In January 1593, Newcastle would be home to the grizzly execution of a Roman Catholic priest. Until the start of the 1530s, English Christianity had been under the supreme authority of the Pope. King Henry VIII, after having his annulment to Catherine of Aragon denied by the Pope, declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England and began having the monasteries closed down. Shortly after, Catholicism would become illegal in England for a period of over 200 years. This is when our story takes place …

Edward Waterson was born in London and raised in the Church of England. His adventurous spirit would see him cross the waters and travel through Europe to Turkey with some English merchants, where he no doubt would have been exposed to a wide variety of cultures and customs. Upon his return to England, Edward stopped in Rome, where his faith would turn to the Catholic Church and he would be ordained as a priest in 1592.

Deciding to return to England would not have been a frivolous decision because of the danger to his life for just being a Catholic priest, but it is one he decided to pursue regardless. Upon arriving in his home country another Catholic priest aboard the same ship, Joseph Lambton, was arrested but Edward had a very lucky escape.

His fortune soon turned, however, as he would be captured less than a year later in midsummer 1593. Joseph, the fellow priest aboard his ship coming to the country, had been executed in 1592 and the sheriff is said to have shown Edward the quartered remains in an effort to frighten him. Regarding these as holy relics, Edward showed no fear and would languish in jail until after Christmas, when he would be executed as a traitor.

He was brought to Newcastle to be executed, but things would not go according to plan. When he was being brought to his place of execution, the horses carrying him refused to move, forcing him to be brought on foot. This unfortunately did not save him and he would undergo the horrific process of being hung, drawn and quartered.

For those of you who may have forgotten what you were taught at school in relation to this particular method of execution, let me remind you. Reserved for the most serious of crimes, the process would begin with the convicted person being brought to a wooden panel by horse, where they would be hanged until almost dead. Just as relief of the noose no longer being around their neck would set in, they were emasculated, disemboweled, beheaded and then chopped into quarters. The remains were often placed aloft in areas where the public could easily see them so as to be a constant reminder of what happens to those who committed such serious offences.

Father Edward Waterson, being recognised as a martyr, was beatified by Pope Pius XI in 1929.

THE ART HEIST

A retired bus driver from Newcastle, who at the time was also a disabled pensioner, I might add, is not the kind of person you might think would be likely to be responsible for one of the most notorious art thefts in Great Britain … but then again you may not have heard the name Kempton Bunton.

Born at the turn of the century in 1900, it would be many years before his name would surface in the media alongside the word thief. Having retired from his job, Kempton was living on £8, which left little funds for himself to use at his discretion. In the 1960s a painting by the renowned Spanish artist Francisco Goya of the Duke of Wellington was to be sold to a rich American art collector, and to be taken to his home back in the United States.

It was at this point that the British Government intervened to keep the painting on British soil, paying the same amount offered by the buyer of £140,000 (the equivalent of over £3 million in today’s money). Kempton was said to be enraged at this, living on the little money he had and still having to pay for a TV licence.

Kempton has said that through simply talking to the guards at the National Gallery he learned a lot about their complex security system, which involved infrared sensors, alarms and a number of other electronic security protocols designed to keep some of the country’s most treasured works of art safe. This would be enough to deter anyone thinking of pilfering the art … that is, of course, if the systems were active and not actually switched off in the morning for the cleaners … which they were.

On 21 August 1961, Kempton had allegedly wedged a bathroom window open and slipped in, leaving with the prized painting in hand via the same window. The police assumed that an experienced art thief had performed the daring criminal act but a letter was then sent to Reuters news agency with a demand that £140,000 be given to a charity that would pay for TV licences for poorer people alongside amnesty for the theft, a demand that was not met.

Four years would pass until 1965 when Bunton contacted a newspaper and, just like in a spy movie, the painting was returned via a lost luggage office in Birmingham. Bunton then turned himself in to the police, admitting theft. During the trial he was only charged with the theft of the frame in which the painting was held, as he returned the painting itself and never intended to keep it.

While he received three months in prison, it was later revealed that it may well have been his sons that were involved in the initial theft and then passed the painting to their father. Bunton, the bus driver from Benwell turned art thief, died in 1976, leaving behind the question of who really took that painting from the National Gallery.

THE HIGHWAYMAN

Gateshead Fell in the eighteenth century was an area with a reputation for being a danger to those unaccustomed to it, and one such local character named Robert Hazlett no doubt took his share of the blame for this reputation. Hazlett was a highwayman who would chance upon coaches passing by and rob them at gunpoint.

This unfortunate career choice would be the end of him when he perhaps got a little greedy and attempted to rob two people in one night on the vast marshland of Gateshead Fell in 1770. His greed saw him rob a woman named Ms Benson, whom it is said reported the highwayman to a mail carrier making his way down the road following her escape from the scene. The mail man did not listen and crossed paths with Hazlett who, much to his later regret, also robbed him, committing a crime now punishable under the Murder Act of 1752, which permitted gibbetting for those caught.

Hazlett was destined to face the law and was eventually caught and taken to court. In an astounding turn of events, it seems that Hazlett had even robbed the judge who was to give him his sentence at some point, giving him little chance of any mercy. He was hanged and his body gibbetted by a local pond as a deterrent for all those who might be tempted to pursue the same career. John Sykes touches on this in his book of local records:

THE HIGHWAYMAN

Hazlett’s gibber, or stob, as it was called, remained here many years after the body had disappeared. On the in closure of the Fell, Hazlett’s pond (which was the name it retained from the circumstance of the gibbet), becoming the property of Michael Hall, Esq., that gentleman caused the pond to be drained and cultivated.

FURIOUS RIDING

In our long recorded history, we have criminalised and legalised many a strange thing. What is legal today might be illegal tomorrow and vice versa.

Reported in the Sunderland Echo in 1935 is a case where a group of men received a fine for a bicycle-related crime. Below is the report:

Fines of 10s each were imposed at Sunderland County Petty Sessions to-day on John Bramley (20), Outram Street, Sunderland; Enoch W. Smith (22) of Mailings Rigg, Sunderland; Joseph Sanders (20) of Henry Street, Hendon; and James Miller (32) of Trewhitt’s Buildings, Sunderland; for riding furiously.

How does one ride furiously exactly? Were they going too fast? Being reckless? Or did their face bear an angry expression? I am afraid I cannot answer that question for you. While it is still illegal today to ride your bicycle under the influence of alcohol and other substances, I can’t see anyone being charged with riding furiously anytime soon.

HIGH TREASON

Nicholas Emil Herman Adolphus Ahlers was living in Roker, Sunderland, when the First World War broke out. He was most likely a well-recognised and respected man, having worked at the German Consulate in Sunderland. In 1914, on orders from his home country, he was tasked with recruiting German men that were of fighting age to return overseas.

Ahlers was arrested and his office was searched, revealing a number of documents that linked him to the departure of local Germans. When he was brought to trial, a number of his countrymen testified against him, including Otto William Martin, of Tunstall Road, who described being approached on a tramcar in Roker and being advised to return home or face consequences. Ahlers’s defence argued that he was unaware of the announcement of the outbreak of war between the two countries and had only been soliciting people for a few hours following this. Soon after this he was found guilty of high treason in Durham and sentenced to death.

One particular quote from Ahlers at his trial that newspapers repeatedly shared was this: ‘Although naturalized, I am German at heart.’ His verdict was appealed successfully as anti-German prejudice was found to have occurred during the trial. Shortly after being released, he moved down south and began going by the name Anderson while under watch from the Government. Both Ahlers and his wife were eventually interned and were kept separate from each other.

While detained in Holloway Prison in 1917, Emma Ahlers, Nicholas’s wife, committed suicide. She had been struggling to cope with the separation that her family now faced and was also unable to sleep. In a letter left under her pillow she asked for forgiveness from Nicholas and detailed her belief that their children would look after each other. Nicholas Ahlers was eventually deported back to Germany in 1919.

THE FATAL TRAIN ROBBERY

On 18 March 1910 two men boarded a train at Newcastle at the start of a journey that was destined to change both their lives. John Innes Nisbit boarded the 10.27 service from Central Station bound for Stobswood Colliery in Northumberland to deliver £370 in wages. When the train reached the end of the line, Alnmouth Station, his body was found under the seat, having been shot in the head five times, with the bag of money missing.