22,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

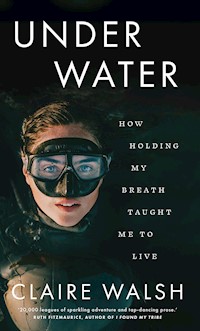

'I needed to breathe. Not the short, shallow breaths that keep you alive … merely existing. I wanted that breath that starts deep down in your being and fills your lungs and limbs with life.' Claire Walsh spent her twenties living the life she thought she was supposed to live, all the while playing hide-and-seek with depression. In her thirties, finding herself single and living with her parents, she decided it was time to chart a different path. In Central America Claire discovered freediving, plunging up to 60 metres below the water's surface without the use of breathing apparatus. It taught her the power of breathwork, but more importantly it taught her how to find freedom in the present moment. Under Water is a candid and captivating story of what it's like to take part in one of the most dangerous sports in the world, and a reminder that sometimes all we need to do is take a deep breath. '20,000 leaues of sparkling adventure and tap-dancing prose.' Ruth Fitzmaurice, author of I Found My Tribe

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

For Mum and Dad

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

1. What do you do?

2. Widths, waves and washing machines

3. Beginnings of breathhold

4. Second most dangerous sport in the world

5. Yatba’ – To follow

6. The thing with feathers

7. Falling hard and falling short

8. Fear

9. Nothing changes if nothing changes

10. Countdown

11. Pause

12. The turtle and the hare

13. Habibi

14. Official top

15. Cold water

16. Softer

17. Burnt popcorn

18. Same same, but different

19. Tangled necklaces

20. I’m okay

21. Welcome home

22. Under Water

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill Books

Photo Section

‘When you find yourself alone in a silent underwater world, you’ll reconsider your previous thoughts and attitudes, and discover new things. Thoughts pass and disappear in a few seconds, and this silence has a calming and nurturing effect on our restless souls.’

Natalia Molchanova, worldchampion freediver (1962–2015)

PROLOGUE

Underwater you don’t hear anything.

Putting my face in the water is like a sigh of relief for my mind. Internal chatter, judgements and criticism fade to a white noise and the rhythmic anchor of my breathing through the snorkel lulls me into the welcomed quietness.

Dancing in front of my eyes, beams of light extend 30 metres below me, showcasing a spectrum of silvers, blues and greens. She’s in a playful mood today, the sea. Winking at me, beckoning me, her flirtatiousness belies her strength. I smile back and she sends a wave to flood my snorkel. Purging my snorkel, I exhale forcefully. Okay, okay! I never was in any doubt who was boss.

I settle into my breathe up, the preparation, the cycle of breathing to bring the body and mind into a state of relaxation before a dive. This sound, the slight dragging of the air through the snorkel, amplified by my neoprene hood and the water, is one I dream about when lying in bed. When sleep evades me, I think of this moment, this soothing lullaby, and just as in the water, my eyelids grow heavier and my limbs soften. This is, after all, an extreme sport of relaxation.

My dive today is 60 metres. This is my deepest dive. The line is lowered and set, the depth marked out by pieces of red electrical tape in a series of lines. At the bottom, above the weight, the bottom plate is waiting for me at the target depth with a little Velcro tag that I’ll tuck in my hood and bring back up as a souvenir, proof that I’ve reached my goal.

In the broader world of competitive freediving, 60 metres isn’t deep – not by a long shot. The world record for women in this discipline, free immersion, is 98 metres. But it’s deep for me, a personal best in fact.

I once described my goal of diving 60 metres to my friend, Máirín, quickly following it up with the customary disclaimer that it isn’t really that deep for a freediver. I proceeded to rattle off the world records, as well as how much deeper friends of mine dived, with each number diminishing my own achievement, desperate for her to understand that this wasn’t deep deep.

Some months later Máirín and I took a spin into town. We parked in the centre of Dublin city, and I started to head in the direction of the restaurant.

‘Nope, this way first.’ Máirín cocked her head and set off in the opposite direction. I rolled my eyes, not in the mood to play along. Where were we going? I was hungry.

We rounded the corner and came to the base of Liberty Hall.

‘How tall is it again?’

‘Fifty-nine metres,’ I whispered.

‘Fifty-nine metres,’ she repeated.

We stood looking, craning our necks to see the top of the building outlined against the grey sky above.

‘Don’t ever try and convince me that’s not an achievement, Claire Walsh.’

I nodded silently. Sixty metres no longer felt small.

Floating on the surface of the water I try not to imagine an inverted Liberty Hall lying beneath me, waiting to be scaled on one breath. Instead, I lift the corners of my mouth to a gentle smile and visualise the dive ahead of me. Peeking through half-closed eyes, I catch sight of those winking, twinkling beams. You’ve got this, the sea whispers.

Setting off with purpose, this is softer than concentration. This is focus, this is trust, this is my mind stepping to the side and allowing my body to trigger the physiological responses that we humans share with dolphins, whales and seals. While 3 minutes underwater to 60 metres and 7 atmospheres of pressure sounds extreme, I have trained my dive reflex. I trust my body and make the adaptations to protect my ears from the increase in pressure, my lungs from the weight of the water around me, to conserve energy and use my precious oxygen efficiently. And when the levels of CO2 in my blood rise and I get that urge to breathe, I trust my mind to find ease beyond the discomfort to allow me to continue on my 60-metre odyssey.

Pulling myself down the rope, head first with my feet trailing behind me, I remind myself how lucky I am to be doing this. I close my eyes and settle into the pull, pull, pull rhythm. My jaw makes the smallest of adjustments as I equalise my ears against the pressure of this dense first 10 metres. My environment begins to fade into the darker colours of the quieter underwater world; my movements, pace and reactions must be measured and match.

Efficiency is key.

Then something magical starts to happen. The space between each pull opens up: pull and glide, pull and glide. I’ve moved through the axis from being positively buoyant, through neutral and into the delicious sinking freefall of negative buoyancy. In that glide there’s a sense of breaking through, of release. The glides stretch further still and it makes me think that this is the closest I’ll get to flying. Peter Pan sort of flying. Second-star-to-the-right sort of flying, effortless soaring-through-the-clouds freedom. The caress of the water on my skin not covered by my wetsuit is all that reminds me that I’m not in the clouds, I’m underwater … but still flying.

The increasing pressure all around – the weighted compression of my chest, the mask being pushed back into my face – lets me know I am sinking. I don’t need to open my eyes to the hazy dark-green surroundings to know that I’m getting deeper. Careful not to make any big movements, I send one last reminder through my body to soften, relaxing my feet, releasing tension from my knees, my belly, my neck. This is my favourite part of the dive: freefall. Light, sounds and the surface have faded. To be here, at this depth, is both incredibly empowering and completely humbling. Pulling my focus inwards, swaddled in this state between awake and asleep, I let go and savour the experience.

Touchdown.

I’m here already? Freefall had passed in a dreamy blur and I was at the bottom. My lanyard carabiner hits the stopper and I reach below to take a tag from the bottom plate. I’ve made it! I allow the smallest, split second of celebration before turning and tucking the little piece of Velcro into my hood. Now for the way back up. I don’t think about racing to the surface or a need to breathe. Out of the corner of my eye I catch the yawning black hole in the coral to my right, locally known as the Arch. I nod, somewhat respectfully, and I settle into a steady, efficient pace that moves me out of the enveloping pressure of depth. The mantra you’ve got this, you’ve got this, you’ve got this helps create a rhythm to my pulls, but more importantly keeps my mind anchored and stops it straying down any unhelpful mental paths. Thoughts use oxygen too and, as I said, the name of the game is efficiency.

I know there’s a risk involved. To the uninitiated, freediving seems extreme at best and downright dangerous at worst. Often considered one of the most dangerous sports in the world, I’ve heard it being described as ‘basically scuba-diving but without the apparatus’. Looking at it that way, taking a deep breath and going down on just the air in your lungs, pulling down on a rope or swimming down as far as you can and then having to come all the way back up, it sounds utterly stressful and even panic-inducing. It doesn’t sound just dangerous but complete lunacy.

There is a risk, but it’s a calculated risk. I know the rules; I am under the watchful eye of my coach, my safety diver. I’m attached to the line by my lanyard. I am doing all I can to keep myself safe. In doing that, I can put the risk out of my mind and focus on the upside: the relaxation.

A unique form of relaxation, freediving to me is a negotiation between body and mind, a quest for a state that requires confidence and concentration, as well as humility and softness. It pierces through surface layers and works with you on a level of intimacy that day-to-day living rarely affords. Striving to hit that balance is like juggling self-awareness, autonomy and trust.

Right on cue, my safety diver appears in my field of vision. I ease into a pull and glide and allow my gaze to take in my surroundings. I notice the changes in light, the colours of the coral along the walls in front of me and take a quick mental picture of how incredible this journey back up looks.

Approaching the last 10 metres of the dive, also known as the low O2 zone, I gently repeat to myself what I’m going to do once I reach the surface. Breathe, remove mask, signal ‘okay’, say ‘I’m okay’. Ten metres to the surface is where most shallow-water blackouts occur. Here divers experience a sudden drop in partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs. With my coach watching my ascent, I feel safe and focus on my surface protocol.

Breathe. Mask. Signal. ‘I’m okay.’

I break the surface and drape my arms over the buoy as I take some active recovery breaths.

‘Breathe, Claire,’ my coach reminds me softly, positioning himself so he can see my face and watch for signs of hypoxia. I know I’m fine – ‘perfectly clean’ – as we freedivers say. Catching my breath, I remove my mask, wipe the water off my face, signal towards him and say, ‘I’m okay.’ I keep breathing and pull my tag from my hood. The buoy erupts in splashes – the customary celebration in freediving. It’s taken me so long to get here, not just to this depth, but to the trust, the appreciation for each moment and the ability to find moments of relaxation amid discomfort. It is indeed worthy of celebration.

Dipping my head below the buoy to detach my lanyard, I look down at where I’ve just returned from. I think of the fear that a few years earlier would have stopped me attempting such a feat and how much I’d have missed out on, not just in the achievement but, like most things, the process to get here.

Freediving has brought me around the world, allowed me to explore underwater scenes that would rival anything from Finding Nemo and created a network and sense of belonging with those that I trust with my life, my freediving buddies. Most importantly, it has nurtured a dialogue, a much-needed mediation between my mind and my body, facilitated by the wisest of teachers, the Breath. It has initiated me into the world of mindfulness: being fully immersed in the moment, without judgement or expectation. Something that had evaded me on land for years.

So what’s it like to take part in the second most dangerous sport in the world? In this extreme sport of relaxation, I haven’t endangered my life, but learned how to live it.

Take a deep breath. Concentrate. Allow your shoulders to fall away from your ears and instead stack the air in your belly, your ribcage expanding confidently, your chest welcoming the stretch. Imagine a wave of oxygen flowing, undulating up your spine and awakening your body as it moves through you. Pausing at the top of the inhale you feel full, fuller than you’ve experienced before. Heart beating against your lower ribs, fingertips tingling with life, your face feels a flash of heat. Smile, get comfortable, be prepared to meet yourself, become reacquainted with yourself and learn that you are capable of more than you anticipated. It’s this pause, this place, this unexplored playground between the inhale and the exhale where the magic is going to happen.

Let’s dive right in.

chapter 1

WHAT DO YOU DO?

Are you still watching?

Hitting ‘continue’, I couldn’t have told you what had happened in the previous episode – or the one before that if I was being honest. I just needed something to go in front of my eyes, a distraction, white noise.

‘Are you getting up today?’ Mum popped her head in the door, hoover in hand, the smell of lemon floor cleaner wafting upstairs. Monday is ‘chore day’, always has been.

‘Not for a while,’ I replied somewhat sheepishly, feeling like a lazy teen who grumbles about having to get out of bed at midday. But I was 32, it was 10 a.m. and my day off.

The innocuous exchange left me feeling anxious and not a little bit guilty. I should be – I caught myself.

Should.

It was a sticking point for me, a word I battled with and against on a daily basis. On my day off I should really give myself a break. Shite, there I went again.

I was back living at home. I had spent the last few years renting, sometimes building a home and other times paying money to condense my life, my living, to a damp single bedroom. Living at the behest of landlords was restrictive at best, and each time my housemates and I received the ‘one month’s notice: we intend to sell/move back into the property’ email, it sent us into a tailspin. Downloading Daft and setting up viewings, searching our emails for the references and documents we’d assembled only months previously. Then to packing, pulling out the cardboard IKEA boxes from storage. You had intended to throw them out last time but stopped yourself, not fully confident you wouldn’t need them again in the near future. Each attempt to find a new dwelling was a race, a competitive one at that, and handicaps like, for example, receiving that mail on 18 December told you that your odds weren’t very good. You’d need a place for an interim stay. That’s how I found myself boomeranging back to my childhood bedroom.

The household sounds – the creak of the third stair, the Morning Ireland music and the kettle boiling – were both comforting and suffocating. I felt like a failure. Mum and Dad were gracious, welcoming, and facilitated the change, but there was no getting around the fact that I was an adult living in another adult’s house and that it was just as hard on them as it was on me. Having my way of living, my adult patterns and routines, replanted into this new–old environment made me feel caged in and exposed. My chest tightened and my skin itched with a sense of restlessness and unease. I was all over the place, literally. At the bottom of my bed was a bag for the week crammed with notes, materials, changes of clothes, empty and stained travel mugs and the inevitable apple I had forgotten about. My clothes were in a suitcase in the corner. Unpacking and hanging my clothes in the wardrobe that I had, in my teens, covered in glow-in-the-dark stars was too much of an admission that I’d be here for a while, that I was officially back living with my parents. The boot of my car had boxes of my belongings that came with me on my commute, with the remainder stacked in a damp corner in the puppet theatre. This temporary way of living was surreptitiously morphing into the norm, leaving me feeling unanchored and unsettled. I quashed these emotions by keeping on the move: teaching, performing and belting it across the M50 to get from one job to the other. I’d keep going, another quick cup of coffee and a chocolate bar for sustenance, the nervous energy fuelling my commute that crisscrossed Kildare and Dublin multiple times a day.

Until I stopped. My days off saw me feeling spent, drained.

I was unrecognisable from the person who stood tall, confident and assured and animatedly addressed the 50 people in front of her. She felt far away at those moments. It was too much – I needed to switch off, dull my senses and recharge. If I could just turn my brain off and rest …

My working week started on a Wednesday. Banging on the door of the bathroom, begging my brother to hurry up. I’d miss my shower window because of the repeated snooze button. I’d grab a quick rinse, more so to wake me up and help cleanse the cloud of grogginess that wrapped around me like the steam of the bathroom. No time for luxuries like breakfast, make-up or dry hair, I’d slop coffee into a travel mug and hit the road.

One of my jobs was teaching drama in a primary school. The 30-minute slots felt unnecessarily like torture. I’d been there years, seen the kids go from adorable full-cheeked junior infants to sullen but very cool pre-teens. The teachers were polite, and some were friendly, but I felt out of place among them, not a real teacher. I’d long since given up on going to the staff room, instead skipping lunch or munching on an apple in the too hot or too cold (but never juuuust right) drama room.

It was five hours of being ‘on’. Some days I managed, lifting the class with my enthusiasm and excitement, relishing their creativity. Other days I felt like a shell, barely able to summon the energy to smile. Those days I felt disappointed in myself, inadequate, and silently promised myself to do better the next week.

The next few days would pass in a blur of smiling, singing, performing, cursing at traffic, anxious glances at clocks and hurried meals shovelled into my mouth while hopping from one foot to the other. I’d stretched myself way too thin. I’d swallow another mouthful of coffee, plaster a smile onto my face and will my energy to keep going just a little bit longer. Hoping to pull off that swan gliding-on-the-water look while swimming like fuck underneath the surface. Maybe it was time to face facts: my swan was more wobble than glide … and she was not a very good swimmer.

Lengthening my spine, I took a deep breath and pulled open the door to the bar. Shit, what’s his name again? Rummaging for my phone, I opened the app: Mark, grand. At the same time, a message came in to let me know he’s running a bit late. It was always the greeting bit that I got nervous about. Should I go in for a cheek kiss? Is a hug overfamiliar? I had a guy stretch his hand out like he was meeting a prospective employer. That was weird. I suppose it was an interview of sorts.

Mark’s missed bus gave me a chance to get settled. I ordered a G&T without the G to disguise the fact that I wasn’t drinking. Turns out Leixlip wasn’t a very sexy place to live, and especially not when you were driving 40 minutes back to it and it was your parents’ house. I slid my car keys off the table and into my handbag and positioned myself to be able to see Mark make his grand entrance.

Oh sweet Jesus, I can’t believe I put on a full face of make-up for this. Lipstick, I’m wearing LIPSTICK, for feck’s sake.

I smiled and listened to him describe his perfect woman: petite, ‘up for the craic’ and brunette. Oh, and big boobs, as he winked lavishly at me. Terrific, I’d hit one on the list, possibly two. Yay me?

His last girlfriend was a model, did I know that? Funnily enough, no, I didn’t. Please tell me more about her. Sex mad was she? Oh, how lovely for her. Couldn’t drive the length of the M50 without pulling in and giving you a – OKAY! I get the idea, thanks. You wouldn’t catch her dead on a dating app? Ah right, was that because of the ‘model status’, do you think?

‘So Claire, what do you do?’

Hands down, this was my least favourite question. Heck, I was even guilty of asking it myself from time to time. Unable to catch the words before they were out of my mouth, I would kick myself, knowing that I’d have to answer the same question.

‘Ahm – well, it depends on what day of the week it is …’

And maybe what time of the year it was and which year it was. I wasn’t trying to be deliberately obtuse or evasive. When it came to my work, it just wasn’t a straightforward question.

Undeterred, he kept going: ‘Have you had many long-term relationships? Do you have kids? Are you renting or have you bought?’

‘Yes. Nope. Nope – I mean, renting. Well, not quite renting. I was renting and now I’m back with my parents …’

I trailed off and let the silence hang in the air as his eyebrows furrowed. I could see him mentally scanning box labels, trying to figure out which one to put me in.

Single?

Living with her parents.

No kids.

She must be really focused on her career then.

‘So, what is it that you actually do?’

Aaaand we were right back to where we started.

‘I do a lot of things. I sing. I swim in the sea, all year round. I work as a puppeteer’ – cue him, as everyone did, making sock-puppet hand gestures and me (mentally) replying with a different kind of hand gesture – ‘I work as a drama teacher, a singing teacher, a movement teacher and occasionally a movement director. I run choirs, gospel choirs, choirs for fun, and I’ve taught people about breathing and how to use their voice. I sometimes run workshops and I sometimes put on shows.’

I could tell people what I did, but it would always come with a disclaimer.

When I was studying for my Leaving Cert, it was coming up to my practical singing exam in music. I

went to meet the pianist accompanying me to go over my piece a week before the exam. I handed over my sheet music, took a drink of water and cleared my throat before apologising.

‘You’ll have to excuse me, I have a bit of a sore throat at the moment.’

He didn’t sympathise, offer me a Strepsil or advise a complicated steam and eucalyptus routine for later. He merely scoffed, maybe even snorted, and replied, ‘You and every other singer I’ve played with.’

That was my introduction to the disclaimer: a rush of words that you offer preceding a task to help others manage their expectations of you. An excuse. A self-deprecating babble. A warning. An explanation.

My answer to What do you do was always preceded by my disclaimer: a well-rehearsed and slick piece with interchangeable phrases to suit the situation – and delivered with a smile. What no one would know was that it continued for way longer in my head once I’d finished the verbal part. Smile gone, this next, internal phase was where things became less structured. Thoughts picked up pace as punctuation took its leave. Words leapfrogged over one another narrating an imagined dialogue with a building sense of urgency.

Maybe it started off as an attempt to cultivate an ‘Ah sure, look’ free-spirited approach to life or to mask a vulnerability or provide a justification. Or maybe it was because when it came to what I did, I felt a little bit ashamed and, a lot of the time, embarrassed.

Swirling the ice cubes left at the bottom of my empty glass, I left my mouth on ‘automatic response’ while my brain struck through the hopeful scenarios I had in my head. Jesus, I don’t know what’s more pathetic at this stage – the fact that I still hold out hope for each first date or the fact that I probably will go on a second date with him …

Women in their 30s are dangerous. Perceived as a predatory bunch, sniffing out partners with frantic urgency underscored by the ominous ticking of their biological clocks … Or so our ‘I’m not ready to settle down yet’ counterparts would have us think. It felt like the trickiest of balancing acts, to want, maybe even yearn, for a partner but to still appear aloof, to be aware of your age, acknowledging and respecting any desire to have a family in the future, but to be ‘chill’ and nonchalant about wanting something serious. Just be yourself but don’t give too much away. Know who you are and what you want but don’t scare him with your independence. Online dating felt more and more like a game: scoring points, collecting weapons, avoiding traps until you qualified for the next level … and then do it all again. It was trying to figure out a set of rules that you’d been handed, that you didn’t know exactly how much you agreed with, but you’d been told that it’s all part of the game. For better or worse, you’d decided to play.

I’d had relationships, even long-term ones. I was someone who saw myself meeting a guy, walking down the aisle, right, together, left, together, buying a house and having kids. Sure I’d work, but to be fair, having studied drama and done a master’s in movement, the details of that career path was always a bit hazy. My relationship goals were all pretty much ‘tick the boxes’. At 28 I found myself newly single and a bit dazed by the prospect that my life might not look like I had always thought. I wasn’t quite ready to reimagine a new path nor was I excited by the potential. Quite the opposite. I was scared; I was embarrassed. The ‘how things should be done’ blinkers were firmly in place, my naivety limiting my imagination. I couldn’t envisage a life beyond that and I didn’t know where to start.

So in my 20s, I had profiles on POF, Match, Tinder and Bumble. The more I chased the original ‘plan’, the further away it seemed. I wouldn’t say that I was – that dirtiest of dirty words in the dating game – desperate – but I was the other dirty word: lonely. It’s not like I didn’t enjoy my own company; I could go to a restaurant on my own, for coffee, to the cinema. I’m great company and entertain myself no end. But I felt like I didn’t fit in with my peers among the engagement/new house/promotion celebrations. Now I was 32, single, couldn’t rent, let alone buy, my own place and my work, although rewarding in the moment, wasn’t on a solid career trajectory … and had me physically and mentally all over the shop. I felt like there was a huge new checklist and I just couldn’t get my shit together enough to tick even one of them off.

I was a reluctant ‘free spirit’ square peg in a ‘settling down’ round hole. No matter how I squashed and pushed and yearned for it, I just couldn’t seem to fit. I was exhausted. I needed more than this. I wanted more than this.

It started off as a musing over Christmas. ‘I think I might go travelling through South America,’ I announced, testing how it sounded out loud. My brother, Matt, had spent a few months travelling the summer before and had planted the seed of the idea. It was peak pantomime season in the puppet theatre and with each ‘oh yes you did’ and ‘it’s BEHIND YOU’, I was inching closer to saying ‘feck it!’ and packing my bags. It’s not that I had a huge urge to travel but more a huge need for change – a change of scenery was as good a thing as the next. It wasn’t going to fix things – where I live, what I do and who, in the future, I might do it with. It was an escape, a knee-jerk reaction, a forceful kicking down of the walls that I felt were moving in on me, an attempt to create space. To breathe.

I hadn’t done the ‘year out to travel’ in my 20s like many of my friends had. I was too busy. I spent most of my 20s playing hide-and-seek with depression, putting my hands over my eyes, and like a toddler’s idea of ‘hiding’, hoping it wouldn’t find me. Spoiler: it did.

I’ve used the same analogy for years to describe depression. It starts with:

It’s like you’re playing baseball.

This in itself is gas. Not only do I know very little about sport in general but I know absolutely feck all about baseball. I went to watch games (Games? Matches? … See what I mean!) when on holidays but all I remember are the snacks and the songs; both excellent.

It’s like you’re playing baseball and are at home base. Then something happens, disorients you, and when you go to place your foot on home base, it’s been moved. You’re no longer safe and, try as you might, your foot can never find that spot.

I don’t know how well this ties in with the actual rules of baseball or whether I’m merging them with the made-up rules we imposed for playing rounders as kids. But what I was trying to describe was the sense of never knowing, never trusting what you thought you knew, what had been familiar and safe.

Sure, there’s sadness, unexplainable sadness, weighty pressing-on-your-chest sort of sadness. But worse than the sadness is the nothingness. Numb, unfeeling. Despondent, unable to feel fear or anxiety but also joy, excitement … or peace. There’s the tiredness that makes mountains out of the smallest of tasks and that can, in an instant, flip into restlessness that has you afraid to stay still.

I think, if I had thought about it long enough, I might have guessed these were symptoms of depression. What I would never have expected was the guilt. Not only do you feel this way but it’s compounded by an unbearable guilt for feeling this way. Compared to others, your life is charmed, uncomplicated and so privileged. How dare you – what right have you to feel like this? Pull yourself together, think positively, go for a walk – snap out of it.

But I wasn’t just looking for attention and, try as I might, attempts to snap out of it resulted in a mounting pressure to hide it. I could feel it … even before I opened my eyes in the morning. It was a heaviness that waited behind my eyes – it didn’t matter whether they were open or closed.

Waking was either one of two things.

Eyelids shooting open, unsure of whether I was even asleep to begin with. My phone would let me know that a few hours had passed but also that it was too early to get up. I needed to get back to sleep. I needed to get back to sleep before my brain, those thoughts, stirred. Rolling over with a quiet caution, I would repeat go back to sleep, go back to sleep to myself like an urgent prayer. I needed to go back to sleep before I was caught.

Too late.

Lying down, the tears would slide down each side of my face, as if running away from each other. I tried to take a deep breath against the gulps of panic tightening my throat, my chest heaving as short and shallow breaths threatened to engulf me. I lay still. I need to ride this out. I know the drill.

I’d long since lost trust in my own judgement and my own emotions as being reliable barometers of any given situation. So I found myself reverting to people who could speak louder, more confidently, seem more assured, to help create my own sense of self, my own recollection of situations. Thoughts and memories mixed and merged, sliding over one another, distorting, warping. With each one I was brought back to events, conversations where a new meaning, a new version revealed itself. And with each retelling the actual people involved fell away and they became stock characters, personas that hissed in my ear, telling me I’m not good enough, that I’m wrong, unkind, ugly, selfish, cruel, fat and failing in everything that I do and unlovable in everything that I am. Each new thought spiderwebbed out into 12 more, each as virulent as the next, triggering waves of anger, shame, hatred and fear. Time, counselling and daylight hours would remind me that this wasn’t truth: it was an onslaught of my demons, taking advantage of my sleeping state to catch up on me. They’d be gone in the morning.

But I was scared.

Do you remember that scene in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, the version with Gene Wilder in it, when the lucky visitors have stuffed their gobs with giant gummy bears, edible toadstools and lollipops the size of tennis rackets, and now stand in confusion beside the chocolate river having witnessed Augustus Gloop’s demise. Wonka, seemingly impervious to the recent events, gestures to a delightful-looking steamboat that emerges from a tunnel to take them on the next part of their tour.

Wonka eases their fears, reassuring them that they’re going to love this, and to start with they do. Cheerfully setting off, this is simply the next part of their adventure, the next step in a day full of unexpected events.

Their enjoyment segues into confusion as they’re plunged into darkness. The boat gathers speed and the disorientated and queasy passengers become more and more agitated as grotesque, disjointed images flash on the walls of the tunnel while the boat hurtles forward into the darkness.

They plead with him to stop, but Gene Wilder’s Wonka becomes alive with the thrill of the chaos. The tension builds to panic, and as a child watching, I became just as unsettled as the characters, wanting to return to the colour, candy and comfort of the ‘world of pure imagination’.

With a chaotic crescendo, the boat stops. The lights come up and it’s almost equally shocking to see everything is the exact same, the horror of the tunnel disappearing as unexpectedly as it appeared.

Many nights I’ve been in that tunnel, stepped on board cautiously. Seeking reassurance but allowing myself to be carried along by the journey. Then it all changed, trips down memory lane, safe, enjoyable memories disintegrated and morphed into events both real and imagined. My fears projected onto a screen in front of me in the darkness. The sound so deafening, that I couldn’t help but listen to words taunt and mock me. I was scared, disorientated, it felt so real, like I had no control over how fast I was going or the images and thoughts I was being assaulted with.

Mr Wonka, I want to get off!

A lot of the nights I gave in, I believed. Tears came hard and fast, lugging despair with them. Sobs travelled from what felt like the centre of my being and I doubled over, not sure whether the pain was emotional or physical at this stage. It felt hopeless. I’m a horrible person and I need to make it up to people. I need to prove that I’m worthy of their friendship, their attention and affection. Their love.

Some nights I gritted my teeth and rode it out like a monstrous rollercoaster, clenching my gut against the gnarled twists and drops. Morning would bring a respite, I was sure … ish.

Other times, waking was as if in slow motion. My alarm would ring:

Snooze. Alarm. Snooze. Alarm … I’m going to be late, really late. But I can’t open my eyes. Glued shut with groggy sleep, I already knew it was there. I knew how I felt before I’d even started the scramble to make up for the time I’d lost hitting the snooze button. My muscles ached and there was a weighted feeling in my chest, in my whole body. The tears had already started. They had their own schedule and agenda, just doing their own thing, irrespective of the situation, of the growing list of things to do in the shortening space of time. I only noticed them when they dropped onto the lap of my pyjamas. With a heavy sigh, I would begin the tussle between calling in sick or starting to get ready. I’d like to say that most of the time I chose to get up, to put one foot in front of the other and slowly start to assemble a presentable version of myself … but I’d be lying.

The warm refuge of the duvet won many, many times. Even years later that sentence affects me like the sound of nails on a blackboard, has me sucking in air through my teeth. I couldn’t shake the notion of being lazy, of letting people down, not being able to ‘brave face’ it. I just couldn’t. It wasn’t so much about not wanting people to see me like that (I didn’t) but more that I wanted to spare people from being around me. To use far kinder language than I would have at the time, I wasn’t the best version of myself. I’d give myself a day in bed, I’d recharge and I’d do better tomorrow.

On those ‘tomorrows’ I would operate in slow motion, dazed, shell-shocked, out of it. (Sometimes I was. I remember having a dosage of an antidepressant that I had to split between morning and evening. In the clunky clamber to get out the door in the morning, I swallowed the two tablets by accident. It wasn’t until I’d reached work that I realised something was wrong. I copped my mistake and rang my doctor. Not ideal but I was in no imminent danger. I’d just be drowsy for a few hours. I fabricated a, no doubt, feeble excuse and had to be driven home. My gratefulness at being back in the safety and privacy of my bed only lasted until I realised I’d have to explain to my then boyfriend what had happened, explain that it was an accident, and deal with his inevitable disgust.)

I was so embarrassed, so ashamed. This was a time where social media was Myspace and the beginnings of Facebook. Thankfully I didn’t have to subject myself to the endless toxic platitudes of positive vibes only. But I knew what I brought to the party. I knew I wasn’t a fun person to be around. My words would spill out and I’d let slip hints at the negative distortion of thoughts inside. I wished I was different. Processing instructions or even innocuous greetings was an arduous task. I’d scan them for criticism or hints that they could see what was going on. I thought everyone could see it, could smell it off me, as if I’d been branded with a giant ‘Depressed’ across the back of my shoulders that let people know how weak and inept I was.

In 2020, when Caroline Flack was found to have died by suicide, social media responded and rallied with messages of ‘be kind’.

In a world where you can be anything, be kind.

Words of encouragement: talk to someone, have empathy and, most of all, be kind.

I remember scrolling through my feed on Instagram. People sympathised and thanked God that they themselves didn’t have mental health issues, that they were positive, strong people.

I stared at my screen. The sides of my vision went fuzzy and my mouth dried up.

I understood the intention: words are important, they hold weight. If ‘positive and strong’ is held up as the opposite of having ‘mental health issues’, what does that make me or anyone else whose eyes shoot open, unexplained, at 4.48 a.m. each morning?

Negative and weak.

Back then it was my biggest fear. Not just that that’s how people perceived me, but that that’s who I was, what I was.

Negative and weak.

Living your life trying to prove to others, to yourself, that you are not is like having a thirst that, no matter how many glasses of water you pour down your neck, won’t be quenched. It’s relentless, rife with misunderstood intentions, polarising and, most of all, exhausting.

My time was spent denying, compensating or apologising. Not out loud or in my actions but, most of the time, in my head. It was a noisy place filled with arguments, rebuttals, push-back, anger and a feeling of being misunderstood. If I could just prove myself to them … It was my full-time job, and I worked around it. It was a game of life-or-death importance and I played with steely determination. I would not get caught. The barrage of symptoms nipped at my heels, tripped me up, and still, I kept stumbling forward.

Of course I fell, I lost the game. Maybe I was just too tired, but in 2008, having just turned 26, I got caught.

You’re It!

Fine, I surrender.

Now what?

A cycle of medications, meetings with doctors and hospital admissions followed. So did anger, so much anger. Diagnoses were made and then changed. Depression, yup, that made sense. Bipolar disorder? Okay, that sounded more impressive, more legitimate. Plus, the women on the ward who had bipolar disorder seemed to have way more fun than the rest of us. They largely congregated in the smoking room while we sat in front of the television, knitting. I’d sometimes peer into the room through the plumes of smoke when I was getting my evening cup of tea from the trolley. It looked so much more … energetic than where I spent my evenings.

At least I had a name for it now. To paraphrase my doctor at the time, ‘that which we call a rose, by any other name, would smell as shit’. Maybe the name wasn’t all that important. Recognising the triggers, the symptoms and how to manage them was what mattered.

Years later, that diagnosis was changed to borderline personality disorder. I’ve barely ever said that aloud, let alone committed it to paper. This one I couldn’t get on board with at all. I had switched from private care to the public mental health system. I was diagnosed by a doctor who had not previously met me, but made his assessment based on the findings of his registrar. I was unable to speak as I listened to him recount information that was incorrect, nuances missed. Tears fell heavily into my lap as I felt helpless, unable to advocate for myself and like I was falling between the cracks.

So I skipped the J1 visa, interrailing, the year in Australia, typical pilgrimages people my age were doing. The road to recovery was the only travelling I did. I don’t know if you’ve been on that road but this was a time before smartphones and Google Maps and boy, let me tell you, it’s easy to get lost. You’d think it’d be straightforward:

Just stay on the road.

What they don’t tell you is that sometimes the road forks and you don’t know which is the best route, or other times the road is like a motorway that you’re driving, the route stretching ahead of you for miles, monotonous and boring miles … so you pop on the indicator and take a detour through a town just for a change of scenery. I spent most of my 20s and early 30s on that road. I’d got lost so many times, I felt I couldn’t ask for directions any more.

I needed to breathe. Not the short, shallow breaths that keep you alive, ticking over but locked into a state of fight or flight, merely existing. I wanted that breath that starts deep down in your being and fills your lungs and limbs with life, opens your eyes to the colours, your nose to the smells and your ears to the sounds, that breath that meets fear and discomfort with a calm certainty that this will pass. Without knowing it, I wanted that breath that places you in the world, lungs open, heart open: living, a part of it.

New Year’s Eve, 2014, I booked a plane ticket.

I’d fly into Panama City and home from Lima, Peru, two months later. Where I went and what I did in between that was wide open; the thought was exhilarating.

I booked a hostel for the first night and after that I’d play it by ear. Of course, the first morning in the hostel I met a lad from Cahersiveen. He had teamed up with a lad from Waterford and they were going to get a boat from Panama to Colombia via the San Blas islands in a few days’ time. Did I fancy joining them? That was the first shrug of my shoulders accompanied by a scared–excited ‘sure’, allowing my path to be shaped by the people I met and opportunities that presented themselves.