Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

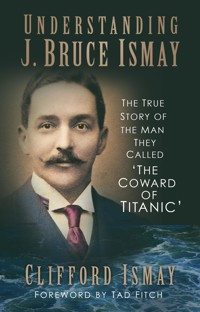

Coward. Brute. Yellow-livered. For over 100 years, J. Bruce Ismay has been the scapegoat of the Titanic disaster. He is the villain of every film and TV drama: a fit and able-bodied man who sacrificed the lives of women and children in order to survive. Some even claim that it was his fault the Titanic sank, that he encouraged the captain to sail faster. But is this the true story? In Understanding J. Bruce Ismay, Clifford Ismay opens up the family archives to uncover the story of a quiet man savaged by over a century of tabloid press. This is a must-read for any enthusiast who wishes to form their own opinion of the Titanic's most infamous survivor.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 301

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the memory of my father Cecil Ismay,a wonderful man who showed me the stars.

Titanic sinking animation on back cover courtesy of HFX Studios, directed by Thomas Lynskey and animated by Levi Rourke. Model artwork by Liam Sharpe and Michael Brady. Animation was produced under the historical guidance of J. Kent Layton, Tad Fitch, and Bill Wormstedt.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Clifford Ismay, 2022

The right of Clifford Ismay to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9071 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Tad Fitch

Introduction

1 The Ismay Family

2 Young Thomas Henry Ismay

3 Purchase of the White Star Line

4 Declining Health

5 Joseph Bruce Ismay

6 Presidency of International Mercantile Marine

7 RMS Olympic, First of the Olympic Class

8 RMS Titanic

9 Carpathia Rescue and Bruce’s Homecoming

10 Bruce Ismay’s Retirement from International Mercantile Marine

11 Life in Ireland

Appendix 1 Extracts From the Archives

Appendix 2 Maryport-Built Sailing Ships of the Nineteenth Century

Appendix 3 White Star Line Handbook

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

FOREWORD BY TAD FITCH

Bruce Ismay is among the most easily recognisable figures of the Titanic disaster. This is partially because he was the chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. However, he is even more recognised due to the tremendous amount of character assassination that he was subjected to in the yellow press following the sinking. This built up a subjective and largely negative caricature of the actual man, one that has unfortunately stood the test of time. Even though it makes for a dramatic story, this portrayal of J. ‘Brute’ Ismay, the so-called ‘Coward of the Titanic’, does not stand up to scrutiny or to a close study of the historical facts.

Besides the negative impact that the rumours and subsequent attempts at character assassination had on Ismay and his family, it also virtually erased the real Bruce, the human, from the historic record. Misconceptions and myths surround nearly every aspect of his involvement with Titanic, from basic information about the design and safety provisions aboard the ship, to his actions during the maiden voyage, and even extending into his later life.

Cliff Ismay has done a great service in writing this biography. Far from being a hagiography designed simply to refute popular myths about the man related to Titanic, here is a true, rounded portrait of his kinsman, the man Bruce Ismay truly was. No longer will we know Bruce just from his actions, both alleged and true, on 14–15 April 1912. In these pages, you will learn about the Ismay family’s background and origins, and how they became involved in shipbuilding. You will learn about Bruce’s father, Thomas Henry Ismay, and how their difficult relationship had a profound impact on his personality. A shy and sensitive individual, Bruce would often hide this side of himself behind a discourteous façade, as a form of compensating. Readers will also learn of his courtship and eventual marriage to his wife Julia, and about their children.

You will learn how, far from being the cold, uncaring individual portrayed in movies, Bruce was described as a charming and warm host by those who got to know him and was extremely charitable to those around him, even if he was described as sometimes being taciturn and abrupt in his business dealings. Readers will also learn how, even though Ismay was greatly impacted and traumatised by the Titanic disaster, he did not withdraw from society or become a recluse, contrary to popular myth. In fact, he attempted to revoke his planned retirement from the International Mercantile Marine, the parent company of the White Star Line, following the sinking. He would maintain multiple business dealings throughout the remainder of his life.

For those who are interested in learning the true history of those aboard Titanic, Cliff Ismay has done an invaluable service. This book will be enlightening and fascinating to many and is a welcome addition to the ‘human story’ of Titanic. I hope that readers will enjoy getting to know the real Bruce Ismay as much as I did.

Tad FitchCleveland, Ohio

Tad Fitch is a member of the Titanic Historical Society and Titanic International Society. He has co-authored six books to date, including Report into the Loss of SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal (2011); On A Sea of Glass: The Life & Loss of RMS Titanic (2012); Titanic: Solving the Mysteries (2019); and the forthcoming Recreating Titanic & Her Sisters: A Visual History (2022).

INTRODUCTION

On Sunday, 14 April 1912, RMS Titanic, at that time the largest moving object built by the hand of man, collided with an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York, resulting in the loss of more than 1,500 lives. From that moment, the actions of Joseph Bruce Ismay, chairman of Titanic’s operating company, the White Star Line, would be scrutinised for over a century.

In modern times, the story has become ingrained in popular culture: ‘the world’s largest, most luxurious ocean liner sinks to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean without an adequate number of lifeboats for all on board’. While the tragedy still captures people’s hearts and minds over a century later, no other individual within the narrative remains more controversial than Joseph Bruce Ismay.

The status of Ismay while aboard Titanic has been open to much discussion over recent years. It would be true to say that Bruce was chairman of the White Star Line and president of the International Mercantile Marine, although he was not on board in either capacity. According to the ship’s manifest, Bruce was listed as a First Class passenger, not as an employee of the White Star Line.

At the time of the collision, Bruce was resting in his cabin and was alerted by a sudden vibration, after which he lay there for a few moments. Not realising that the ship had struck ice, his first thoughts were of the colossal ship losing a propeller blade. A short while later, he left his cabin, meeting a steward in the corridor outside his room. Bruce asked what had happened, but at that point the steward was also unaware of the unfolding horror awaiting everyone on board. Bruce immediately returned to his cabin and hurriedly put on a dressing gown and a pair of slippers, before making his way to the ship’s bridge. There he met Titanic’s captain, Edward J. Smith, who informed him that the ship had struck ice.

Bruce asked of Smith, ‘Do you think the ship is seriously damaged?’

Smith replied, ‘I’m afraid she is.’

On hearing Smith’s reply, Bruce made his way to the lower decks, where he chanced upon the ship’s carpenter, and the severity of the damage was explained to him. In the main companionway, Bruce also met Joseph Bell, the ship’s chief engineer. Bell explained that the ship was taking on water and it was possible that, given the severity of the damage, the watertight compartments might not control the flooding; he also felt the pumps might only be sufficient to keep the ship afloat for one hour, or perhaps two.

Bruce proceeded back to the ship’s bridge, and, upon arrival, he heard the order being given to break out the lifeboats. The chairman of the White Star Line then made his way over to Titanic’s starboard-side Boat Deck, where he met a ship’s officer. Bruce informed him of the urgency of the situation and promptly assisted in putting women and children into many lifeboats before boarding the last lifeboat to be successfully lowered from the starboard side.

The ensuing American inquiry into the Titanic disaster did not directly attach any blame to Bruce, although it was felt that his mere presence on board may have contributed to Captain Smith’s decision to increase speed. The following British inquiry cleared Ismay of any blame.

Immediately following the sinking of Titanic, Bruce Ismay was attacked by the British and American press, who, at least in part, held Bruce responsible for the Titanic disaster and for the fact that he was saved while a great many others lost their lives. American newspapers, especially those owned by Randolph Hearst, labelled him as the ‘Coward of the Titanic’ and suggested that Bruce’s name should be changed to J. ‘Brute’ Ismay, while also suggesting the company’s name should be changed from White Star to Yellow Liver.

To what extent can we question the accuracy of these criticisms?

1

THE ISMAY FAMILY

To understand Joseph Bruce Ismay, it may be necessary to look back in time, not only into his life but also to examine his family history. Many Ismay family members have their roots in Cumbria, or Cumberland as it was known before English county boundary changes in 1974. The Ismay family can be traced back to at least the turn of the sixteenth century, and possibly as far back as 1066, with the Norman invasion of Britain. The surname Ismay is derived from the name of an ancestor, ‘the son of Ismay’, with the name originally being a rare girls’ name in thirteenth-century France. The name managed to survive, later becoming a surname.

For the purpose of this chapter, we shall begin in the ancient parish of Uldale, Cumbria. Uldale is a small village located in an isolated area, among the fells of the northern edge of the English Lake District and overlooks the River Ellen which flows into the Solway Firth at Maryport.

Originally, a ninth-century Norse-Irish settlement existed there. The name Uldale comes from the Old Norse language ‘úlf’, meaning ‘wolf’. Dale-wolves once roamed the fells here in abundance.

A certain Daniel Ismay lived in the village with his wife, Ann. He was born in Bromfield, a small hamlet 10 miles to the north-west of Uldale. He had met and fallen in love with Ann Cowx, the daughter of John Cowx, a prominent Uldale family. Daniel and Ann, already heavily pregnant with her first child, were married in St James’ Church, Uldale, on 12 November 1754, with their first son Thomas being born two months later.

In the eighteenth century, Uldale was a small village with a population of around 350 inhabitants. Villagers were mainly employed in farming, copper mining and quarrying for limestone. Daniel plied his trade as carpenter in and around Uldale for a great many years, during which time Ann gave birth to seven sons and five daughters. The last four born were all boys, but sadly, none of these four boys lived past their fifth birthday.

Thomas was the eldest of the seven brothers and attended the local grammar school, which was located close to his home to the south-east of Uldale village. As a young boy, his passion was carving pieces of wood which he would find lying around in his father’s workshop. Mostly he carved small boats, inspired by pictures he found in his favourite books, and he became very good at it.

At that time, farming was the main business of the Ismay family. However, like his father, Thomas’ profession was a carpenter, working alongside his father for several years. In July 1777, Thomas married Elizabeth Scott, soon after her birthday, both being 22 years of age. Soon after their marriage, Thomas and Elizabeth, who was heavily pregnant with their first child, decided to seek a new way of life and relocated to the seaside town of Maryport, Cumbria, an upcoming town which was 18 miles to the west of Uldale and situated on the shores of the Solway Firth. It was here that their first child, Henry, was born.

After several years plying his trade as a carpenter in Maryport, Thomas was enlisted as a soldier with the British Army, becoming involved with the British invasion of Guadeloupe. Thomas was subsequently captured by the French and remained a prisoner in Guadeloupe until his death in 1795, at just 40 years of age.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Maryport had a population of just under 4,000 inhabitants. The main income in the town was from importing timber from America and exporting coal to Ireland. There were three main shipbuilding yards situated on the town’s River Ellen, which, being a narrow river, necessitated most ships to be launched broadside. Therefore, ships built in Maryport were typically between 30 and 450 tons, of timber construction and mainly designed for the American, Baltic and West Indian trade routes.

One of Maryport’s first shipbuilding yards was owned by Joseph Middleton, and one of his ships, the Vine, a three-masted schooner built in 1812, was built for and first mastered by Henry Ismay, the son of Thomas and Elizabeth. In January 1800, the 23-year-old Henry married Joseph Middleton’s eldest daughter, Charlotte.

Henry had been employed as Master Mariner throughout much of his adult life. His regular trading route was between Liverpool and Newfoundland, with regular stops at Queenstown in Ireland for supplies. He loved the challenging life that his profession demanded and largely remained at sea until his retirement when, along with his beloved wife, he took on a small grocery shop in Maryport’s High Street, where he traded for many years as grocer and flour dealer.

Joseph Ismay, the third son of Henry and Charlotte, was christened on 27 April 1804 in the Presbyterian Church, Maryport, the town in which he would later work as a shipbuilder, ship owner and timber merchant. Following in his father’s footsteps, Joseph entered into the seafaring world at an early age, finding employment as a foreman shipwright at the Middleton yard, which was now owned by his uncle, Isaac Middleton.

Joseph Ismay married Mary Sealby, daughter of John Sealby, a prominent gentleman of Maryport, immediately taking his new bride to live in the small house that he had purchased some three years earlier. This house was situated in Whillan’s Yard, which was a narrow thoroughfare between two of the main streets in the town and was very close to his father’s house on High Street. Being a narrow thoroughfare, all the houses were small and cramped together, and consequently, conditions in this tiny house were quite restrictive, but it made an acceptable first home for the young couple.

Four years later, their first son, Thomas Henry Ismay was born. He was destined to become one of the most prominent ship owners of his time.

2

YOUNG THOMAS HENRY ISMAY

Thomas Henry Ismay has been described as the greatest shipowner of the Victorian era. He was born in 1837, the year in which Queen Victoria took the throne, and died in 1899, just two years before her death. He was the first son of Joseph Ismay and was born in the family home in Whillan’s Yard, Maryport, on 7 January 1837. Four years later, the family had increased to four children. Charlotte and Mary were twins, and three years later another sister, Sarah, was born.

This small three-roomed house was now overcrowded, and so they bought a larger house near the family’s shipbuilding yard. Their new home was named Ropery House, so named because all the ropes connected with the shipyard were laid out nearby. The house had four main rooms and three attic rooms, thereby making an ideal home for the expanding family. It was here that their fifth child, John Ismay, was born, when Thomas was 10 years old.

Soon after moving to Ropery House, Thomas’ father, Joseph, began his own business as a timber merchant and shipbuilder, he was also Maryport’s first shipbroker and had a share in four ships trading with the port. One of the firms he traded with was Imrie Tomlinson, of Liverpool, with which his son Thomas would later be apprenticed.

As a young boy, Thomas spent many hours at the quayside. He loved to talk with the sailors and enjoyed watching the ships entering the port and leaving for lands afar. Although he was very young, he demonstrated his keen interest in anything to do with the sea and ships, even joining the sailors in the habit of chewing tobacco, soon becoming known as ‘Baccy’ Ismay.

Thomas had a happy childhood, but he had to assume a degree of responsibility at an early age. When he reached the age of 12, his father Joseph became very ill and journeyed south to Malvern, in the hope that treatment at the town’s legendary and fashionable spa would aid his recovery. During his father’s time away, the young Thomas helped look after his mother and his younger brother and sisters, as well as keeping the garden in good order, the produce of which would help provide a welcome meal at the family table. He also assisted with his father’s business in the hope that all would be ready for his father’s return.

His parents soon realised the boy’s true potential, so when he left the local school, they arranged for his further education to be completed at Croft House School, Brampton, near Carlisle, almost 40 miles to the north of Maryport. This was considered, at that time, to be one of the best boarding schools in the north of England and drew pupils from all over northern England, Scotland and Ireland. The young Thomas probably travelled to school on the newly opened Maryport–Carlisle Railway, the construction of which began the year he was born. It had only been in operation since 1841 and at that time was considered by many people to be an advanced form of transportation.

The school was run by a Mr Joseph Coulthard, his wife, two sons, a daughter and four assistant masters. It comprised two large houses, standing about 200 yards apart. In one were the residential quarters and in the other, classrooms.

The curriculum taught was considered progressive for that time and mainly consisted of English, arithmetic, classics, modern languages, philosophy, deportment, penmanship, drawing and music. Philosophy included astronomy, chemistry, physiology, botany and geology, while deportment included dancing, drill and gentlemanly bearing. While he was at this school, Thomas loved nothing better than to build model boats in his spare time and rig them according to their class. Once they were complete, he would sail them on a nearby pond, much like his great grandfather Thomas had done.

An account of Thomas’ days at Croft House was written by one of his contemporaries, half a century later:

Thomas Henry Ismay was, along with myself, and many others, a pupil at Croft House under the late Mr Coulthard, and survivors of that company will remember well the dark-complexioned lad, with dark piercing eyes, whose hobby was the sea, whose ambition was a seafaring life, and who never seemed so happy as when engaged in fashioning a miniature sailing vessel with a pocket knife out of a block of wood, rigging it with masts and sails all according to the orthodox rig of its class and then sailing it on the pond at Irthington. Anything affecting the sailing of ships touched him in a tender place and awakened those instincts which were destined to make his name famous throughout the world. Ismay finished his education at Croft House taking the general course of the school which was regarded as a very good course and far ahead of general notions of education in those days. I doubt whether any of his school-fellows or teachers would, in his school days, have predicted that such a future was in store for him.

After only one year at Croft House, Thomas’ father died suddenly, aged only 46. It was Thomas’ great-uncle, Isaac Middleton, who arranged for Thomas to be apprenticed with the shipbrokers Imrie Tomlinson, who Isaac knew well, as he and Thomas’ father had conducted business. It followed that at the age of 16, Thomas began his apprenticeship at 13 Rumford Street, Liverpool. At that time, there was a regular sea route trading between Maryport and Liverpool, and it is likely that this mode of transportation was chosen for his journey.

From that moment, Thomas could be considered to be the architect of his own fortunes. His father had been successful as a shipbuilder in Maryport, but Thomas arrived in Liverpool with very little capital, yet his young mind was full of ambition and aspiration, enough to position him at the gateway to his career.

While serving his apprenticeship, Thomas had established a good relationship with Liverpool merchants, mainly because of his honesty and the prompt attention he gave to their affairs. After three years with the firm Imrie Tomlinson, Thomas decided to gain some experience of life at sea and of the world, and so embarked on a series of voyages which lasted almost a year. His first voyage was arranged with Jackson & Co. of Maryport, sailing from Liverpool to Chile on board their vessel Charles Jackson, a three-year-old barque of 352 tonnes. Under the command of his uncle, Captain George Metcalf, Charles Jackson sailed from Liverpool on 4 January 1856, destined for South America, a journey that took almost a year.

Interestingly, several years later, Charles Jackson came under the ownership of T.H. Ismay & Co. for a short time, before being returned to the ownership of her builders, R. Ritson & Co. During his time away, he had many adventures and thoroughly enjoyed his experience. On his return to Liverpool, in the autumn of 1856, Thomas set about putting his affairs in order.

At 20 years of age, Thomas had already become a very astute businessman and was ready to make his mark. As Thomas had only been 13 years old when his father died, his uncle Joseph Sealby was made a trustee of his father’s estate. Apparently, Sealby had assigned part of the family business to his son John, particularly the management of two ships partly owned by Thomas’ late father, and now by Thomas – the ships being named Mary Ismay and Charles Bronwell.

Thomas visited Charles Bronwell while she was moored in Liverpool and asserted to the captain of the vessel that he did not consider his cousin, John Sealby, a competent person to manage the ship. This resulted in several heated exchanges between John Sealby, Thomas Ismay and ultimately Joseph Sealby, trustee of the estate. Joseph soon decided that he no longer wished to have further business with his nephew and sold his shares to Thomas. His divisive strategy had worked, and Thomas had successfully freed himself from his trustees.

While still working for the firm Imrie Tomlinson, Thomas met a retired sea captain named Philip Nelson, who was also a son of Maryport. Nelson had an interest in anything to do with ships, and his firm was known as Nelson & Company. During the year 1857, Nelson and Ismay decided to create a shipbroking business together. This partnership became known as Nelson, Ismay & Company, but as Thomas was under 21 years of age, the articles of agreement could not be signed until January of the following year.

Together, they took offices in Drury Buildings, 21 Water Street, Liverpool. Nelson was extremely cautious in all he did, whereas Ismay was full of youthful enthusiasm for the very latest design in ships. Iron in shipbuilding was not yet popular, but the youthful Thomas was convinced that the day would come when practically all ships would be built of iron.

Two years into the partnership, they commissioned their first ship, Angelita. Registered in 1859, Angelita was built by Alexander Stephen & Sons, a Scottish company specialising in the development of steam power and the use of iron for shipbuilding. Angelita was a small brigantine of 134 tonnes, which proved profitable for the company, with orders being placed the following year for two larger vessels, Mexico, a 187-ton schooner, and Ismay, a 447-ton barque. It was Ismay’s insistence that all three ships would be iron-built, and eventually – with some reluctance – Nelson agreed. The three new ships were built at Stephenson’s Kelvinhaugh yard in Glasgow and given the yard numbers 21, 29 and 30.

However, at the beginning of 1862, following the loss of Angelita, Nelson and Ismay decided they could no longer work together, and the partnership was dissolved by mutual consent on the first day of April 1862. Thomas agreed to take responsibility for all debts due to and owed by the firm. When the partnership with Nelson ended, Thomas moved his business to 10 Water Street, Liverpool and became known as T.H. Ismay & Company.

Around the time that the order had been placed for Angelita, Thomas met Margaret, the eldest daughter of ship owners Luke and Mary Bruce. They fell in love almost immediately, and it was a love that was to last throughout their whole lives. They married on 7 April 1859 at St Bride’s Church, Percy Street, Liverpool. It was by no coincidence that this was also the wedding anniversary of Thomas’ father and mother.

Thomas and Margaret were blessed with five daughters and four sons, one of whom, Henry Sealby Ismay, died at only eighteen months. Their eldest son, Joseph Bruce Ismay, was destined to succeed his father as head of the White Star Line and to become infamous to many as the man who left RMS Titanic, as the ship slipped beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic.

Margaret, or Maggie, as Thomas called her, was a wonderful wife and mother. She supported her husband in all that he did, and the couple were perfectly devoted; each lived for the other and for their children.

3

PURCHASE OF THE WHITE STAR LINE

Thomas Henry Ismay, now a director of the National Line, purchased the name flag and the goodwill of the White Star Line in 1867 for £1,000. The line was originally owned by Henry Threllfall Wilson and John Pilkington, but in 1863 Pilkington left the company to be replaced by James Chambers, also from Cumbria, who had commissioned the company’s first steamship, Royal Standard.

After two years’ trading, mainly on the Australian route, Thomas was approached by Liverpool merchant Gustavus Schwabe, who explained that his nephew, Gustav Wilhelm Wolff had recently partnered with Mr Edward Harland for the purpose of shipbuilding in Belfast and had recently built some iron ships of a revolutionary design. Schwabe was already a large shareholder in this company but had been told that no more shares were available. Being anxious to invest more money into shipping, he suggested to Thomas Ismay that he was the ideal man to start a new company of steamships, mainly to work the North Atlantic trade.

Schwabe said that if Ismay would agree to have the steamships built by Harland & Wolff, he would back the scheme without exception, and persuade other Liverpool businessmen he knew to do the same. So, in 1869, the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company was formed, with a capital of £400,000, of which Thomas subscribed a large percentage. Other shareholders included Edward James Harland and Gustav Wilhelm Wolff.

Harland & Wolff were immediately commissioned to build four ships, the first of which was Oceanic, followed by Atlantic, Baltic and Republic. These original steamers were all of similar design, with such improvements as were found necessary through the experience gained by their use in service. The order was later increased to six ships, the additional two being Adriatic and Celtic, which were 17ft longer.

With the appearance of Oceanic in the Mersey, the old liners looked outdated, as the new ships were long and narrow, appearing more like a yacht than an Atlantic liner. The design was completely revolutionary. The old high bulwarks had completely disappeared and were replaced by iron railings so that the sea could flow freely from the deck. The deckhouses had gone, and the decks were built out to the full width of the ship for the first time.

These designs were Edward Harland’s, but on seeing them, Thomas Ismay suggested several alterations which Harland & Wolff instantly incorporated. He suggested moving the main saloon and all First Class accommodation amidships, where the vibration from the engines would be least noticeable. He also suggested that cabins should be given a larger porthole, thereby making them bright and airy.

Oceanic and her sister ships made all other Atlantic steamships appear outdated almost overnight. Once again, Thomas had set new standards for ocean-going liners, and under his control, the company was set to become a world leader.

This was the beginning of the wonderful partnership that existed between White Star Line and Harland & Wolff. The heads of each of the firms became personal friends and a mutual trust and respect began to grow. With the exception of just one ship, Laurentic (II), the ships were all built on a cost-plus basis, with a percentage of the total build cost added, which was the builder’s profit.

Harland & Wolff were given absolute freedom to design and construct the finest possible ships, which they did exceedingly well. No other shipbuilder would receive a White Star contract, while Harland & Wolff agreed not to build ships for any firm that was in direct competition with the White Star Line. It was an agreement that worked very well for both the White Star Line and Harland & Wolff.

Following the death of William Imrie in 1870, his son, also named William, a close friend of Thomas for over fifteen years, transferred the whole of Imrie Tomlinson to T.H. Ismay & Company. Instantly the firm became known as Ismay, Imrie & Company and became a subsidiary of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company. The head office of Ismay, Imrie & Company remained at 10 Water Street until the new offices at 30 James Street were completed in 1898.

Thomas wished to ensure that his passengers would experience the best possible crossing while on board his vessels. In consequence, he prepared a letter which would, while Thomas was head of the line, be given to every captain upon accepting command of a White Star vessel. This example was sent to Captain Digby Murray on taking command of Oceanic, on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, on 2 March 1871:

Captain Digby Murray

February 1871.

Dear Sir,

When placing the Steamer Oceanic under your charge, we endeavoured to impress upon you verbally, and in the most forcible manner we were capable of, the paramount and vital importance above all other things, of caution in the navigation of your vessel, and we now confirm this in writing, begging you to remember that the safety of your passengers and crew weigh with us, above and before all other considerations. We invite you also to bear in mind that while using due diligence in making a favourable passage to dismiss from your mind all idea of competitive passages with other vessels, concentrating your whole attention upon a cautious, prudent, and ever watchful system of navigation, which shall lose time, or suffer any other temporary inconvenience, rather than run the slightest risk which can be avoided. We are aware that, in the American Trade where quick passages are so much spoken of you will naturally feel a desire that your ship shall compare favourably with others in this respect, and this being so we deem it our duty to say to you most emphatically that, under no circumstances, can we sanction any system of navigation which involves the least risk or danger.

We request you to make an invariable practice of being yourself on deck when the weather is thick or obscure, in all narrow waters, and whenever the ship is within 60 miles of land; also to keep the lead going in either of the last mentioned cases, this being, in our opinion, a measure of the greatest importance, and of undoubted utility.

We attach much importance also to giving a wide berth to all headlands, shallow waters, and other positions involving possible peril, and we recommend you to take cross bearings where practicable when approaching the land, and where this is not feasible you will then do well to take casts of the deep sea lead, which will assist in determining your locality.

The most rigid discipline on the part of your officers should be observed, whom you will exhort to avoid at all times convivial intercourse with passengers, or with each other, and only such an amount of communication with the former as is demanded by a necessary and business-like courtesy. We must also remind you that it is essential to successful navigation that the crew be kept under judicious control; that the lookout be zealously watched, and required to report themselves in a loud and unmistakable voice after each bell sounds, as in this way you have a check upon their watchfulness.

We have full confidence in your sobriety of habit, but we may nevertheless exhort you to abstain from stimulants altogether, whilst on board ship (except in so far as the requirements of health may demand) endeavouring at the same time to imbue your officers, and all those about you, with a due sense of the advantage which will accrue not only to the Company, but to themselves, by being strictly temperate, as this quality will weigh with us in a special manner when giving promotion.

The consumption of coals, stores and provisions and indeed all articles constituting the equipment for the voyage should engage your daily attention, and so far as possible at a regular fixed hour, in order that you may be forewarned of any deficiency which may be impending, and that waste may be avoided, and a limitation in quantity determined on while it is yet time to avail of this expedient. The vessels of the Company have always been hitherto, and will be so long as the direction is in our hands provided with a full and complete outfit under these various heads, but where waste and thoughtless extravagance occur on the part of those in charge of any of the departments, it will be your duty to check such reckless and dangerous proceedings, and take measures to bring about an immediate change. We count upon your reporting to us without fear or favour all instances of incapacity or irregularity on the part of your officers or others under your control, as in this way only can we determine upon their respective merits, and hope to surround you with an efficient and reliable staff.

After having thus dwelt somewhat minutely upon matters of detail connected with your command, it may not be unprofitable to impress you with a deep sense of the injury which the interest of this Company would sustain in the event of any misfortune attending the navigation of your vessel:-

First. From the blow which such would give to the reputation of the line.

Second. From the pecuniary loss which would accrue the Company being their own insurers to a very large extent: and

Third. To the interruption of a regular service upon which much of the success of the present organisation must depend.

We may also state that, if at any time you have any suggestions to make, bearing upon the steamers; their outfit; or any matter connected with them and the trade, we shall at all times be glad to receive, and consider such.