Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

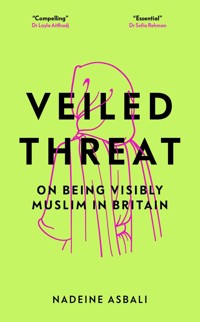

Nadeine Asbali would be the first to say that a scarf on a woman's head doesn't define her, but in her case, that's a lie. Nadeine's life changed overnight. As a mixed-race teenager, she had unknowingly been passing as white her entire life: until she decided to wear the hijab. Then, in an instant, she went from being an unassuming white(ish) child to something sinister and threatening, perverse and foreign. Veiled Threat is a sharp and illuminating examination of what it is to be a visibly Muslim woman in modern Britain, a nation intent on forced assimilation and integration and one that views covered bodies as primitive and dangerous. From being bombarded by racist stereotypes to being subjected to structural inequalities on every level, Nadeine asks why Muslim women are forced to contend with the twin oppressions of state-sanctioned Islamophobia and the unrelenting misogyny that fuels our world, all whilst being told by white feminists that they need saving. Combining a passionate argument with personal experience, Veiled Threat is an indictment of a divided Britain that dominates and systematically others Muslim women at every opportunity.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 331

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i“A compelling exploration of how a piece of cloth can transform your role in the fabric of society. Nadeine Asbali skilfully navigates the complex interplay between fear, bias and security policies like Prevent to unveil the Islamophobia faced by visibly Muslim women and the demonisation of an entire community. From counter-terrorism to Turkey Twizzlers, this book enlightens and entertains simultaneously.”

Dr Layla Aitlhadj, director of Prevent Watch

“Veiled Threat is more of an invitation than a threat. Nadeine Asbali presents, through vignettes of her life, some of the most pertinent and universal flashpoints in the lives of British Muslims. She expertly handles the varying issues of heritage, identity, Islam, racism, feminism, humanity, motherhood and even joy with thoughtfulness and insight. Despite some of the heavier topics covered, Nadeine’s unique narrative style makes this an enjoyable whilst informative read. An essential addition to school curricula and home libraries.”

Dr Sofia Rehman, author of A Treasury of ‘A’ishah

ii“As a visible Muslim and a dedicated doctor, Veiled Threat is a refreshing and eloquent testament to the nuanced challenges faced by Muslim women and men in modern-day Britain. Nadeine Asbali’s enquiries into the intricate intersections of misogyny and Islamophobia provide a profound understanding of the unique burdens borne by Muslim women, illustrating the systemic and institutional biases that disproportionately affect us. Her critique of white feminism is a vital contribution to the discourse on intersectionality, encouraging readers to engage in meaningful conversations about inclusivity and solidarity within the feminist movement. In addition, Nadeine’s exploration of social class as a compounding factor in experiences of Islamophobia enriches the narrative, painting a comprehensive picture of the challenges faced by Muslims across different socio-economic strata. This book not only resonates with my personal experiences but also advances the discourse on diversity, inclusion and the intricate intersections of Muslim identity. A must-read for anybody passionate about creating a more inclusive and informed society, promoting dialogue and solidarity across diverse communities.”

Dr Kiran Rahim, paediatrician and Instagram educator

“A powerful journey into the complexities of identity and visibility as a Muslim woman in contemporary Britain. Nadeine Asbali, with poignant honesty, explores the impact of societal expectations and the intersectionality of Islamophobia and misogyny. Through vivid anecdotes and incisive observations, Veiled Threat challenges stereotypes, exposing the struggle of being perceived as an outsider in one’s own home. It’s a compelling study of resilience, sisterhood and the profound influence of the hijab on one’s sense of self.”

Rabina Khan, writer and former Liberal Democrat councillor

iii

v

In the name of Allah, the most beneficent, the most merciful.

This book is for my sisters in faith, my fellow visibly Muslim women. Those, like me, whose existence is built upon the precarious ground of policy and stereotype, penned in between the twin oppressions of misogyny and Islamophobia, our voices drowned out by the endless din of those seeking to save us and others condemning our covered bodies as foreign, menacing, un-British. This is for us: we whose very presence on this racist island is resistance. Here’s to refusing to be fetishised, maligned and criminalised into integrating, into belonging. Here’s to refusing to prove our humanity to white feminists who trample over our dead bodies, politicians who call us letter boxes and a nation that never bothers to see us as anything but meek victims, convenient political mascots and veiled threats all at once.vi

vii

‘The woman who sees without being

seen frustrates the coloniser.’

Frantz Fanon

viii

Contents

Introduction

I’d be the first to say that a scarf on a woman’s head doesn’t define her, but in my case it’s a lie.

My racialisation occurred overnight. One day I was a white(ish) child with a slightly foreign-sounding surname and the next I was something sinister and threatening, perverse and foreign. Suddenly, I was an outsider in the town I called home. I was called ‘Taliban’ on the bus and grown adults steered their children away from my covered head as though my otherness was contagious, like the flu. Teachers swooped in to save me from the chauvinistic father they imagined to be the cause of my newly covered hair. I didn’t know it as a mixed-race teenager, but I had been passing as white my whole life. My passably English-sounding first name, my white mother and my homelife of Turkey Twizzlers and Tracy Beaker had sold me the myth that I was like anyone else – that I had access to Britishness by birthright. That it could never get taken away.

2But then the façade, and the entire life I had built upon its premise, collapsed. No longer a normal kid who went under the radar, I learned that being visibly Muslim in a nation as hostile as Britain means forever living in the margins. A perpetual victim, a ceaseless threat. The object of someone’s fetish or someone else’s white saviour complex. A political symbol, a harbinger of extremism. A terrorist’s wife or a woman desperate to whip off her headscarf. Never, ever simply ourselves.

Still, I almost didn’t write this book.

I thought, it’s so rudimentary, isn’t it? So obvious. So typical. A hijabi writing about the hijab, as though the only thing Muslim women are capable of writing about is what’s on our heads rather than anything that might happen to be inside them.

I wondered if anyone would care about what a Muslim woman had to say about a piece of cloth. I doubted if the things I had to say were even relevant any more. Look around you, I told myself, there’s a hijabi in pretty much every make-up advert on TV these days. Nadiya Hussain is a household name. Primark puts headscarves on its mannequins. I haven’t been asked by a student if Muslims are ‘the ones who shoot everyone’ in at least half a decade. Let it go!

But that’s the point. Muslims shouldn’t have to prove our humanity, our worth. We shouldn’t have to win gold medals or baking contests to matter. We shouldn’t have to 3fold ourselves up and squeeze through the narrow definitions that society dictates of us in order to be heard. We shouldn’t have to dress a certain way, behave a certain way, think a certain way in order for people to listen up.

Well, this is me forcing you to listen. I may be a Muslim woman but I don’t speak for us all, so if you have come to this book for representation – to tick your book club’s diversity box for the month – look away. I am tired of defending, explaining, justifying my existence away. I am exhausted from constantly condemning actions that aren’t mine, obscuring parts of me that are unpalatable to the only place I have called home. This book is not about what all Muslim women think; but it is about what it means to be visibly foreign in a nation intent on forced assimilation and integration, that views covered bodies as primitive and dangerous. It is about grappling the twin oppressions of misogyny and Islamophobia, and how Muslim women are perpetually stuck between patriarchal cultural norms in our own communities, racist policy-making, white saviour feminism and the unstoppable Islamophobia machine. And it is about the gleaming joys to be found in those margins, too. The sisterhood, the community. The beauty, the fulfilment. It is about all the ways the hijab has defined me – for better and for worse.

As I wrote this book, Muslim women were suddenly back in the news again. In the past few months alone, France has banned girls from wearing anything even remotely 4Muslim-looking in state schools – including co-ord sets and high-street maxi dresses. Palestinian women are giving birth in bombed-out hospitals with no anaesthetic whilst the world sanctions it as self-defence. France (yes, again) has just prohibited its athletes from wearing the hijab during the upcoming 2024 Paris Olympics, and we’re over a year on from white feminists saving Muslim women in Iran by livestreaming themselves shaving their heads. The spectre of a British Prime Minister referring to us as ‘letter boxes’ hangs over our heads. The name Shamima is practically a racist slur. And the world’s most viral misogynist has become a Muslim and converted scores of our brothers, husbands and sons to the idea that we are subhuman.

From Europeans colonising the mysterious, primitive ‘east’ full of sensual veiled women being traded for camels to today, where wearing an H&M maxi dress to a French school is illegal if your name is Khadija but not Chloe, Muslim women have come no further in unshackling ourselves from the double jeopardy of Islamophobia and misogyny. The same old myths, stereotypes and paradoxes that have always defined us still prevail, confining us in ways that, ironically, we are told only the scarves on our heads are to blame for.

So, to answer my own question: yes. Writing about the hijab does matter now as much as it ever has done. Perhaps more. I can’t imagine an archetype of visible foreignness more contested and political than the hijab and thinking 5about what it means to be visibly Muslim in Britain is to get to the very core of the Islamophobia, misogyny and racism that rules our society. It is to expose how state surveillance, geopolitics and social expectation compete on the battleground of our bodies. It is to interrogate liberalism’s unshakable hatred of covered bodies. It is to hold this nation to account for what it does to those who don’t assimilate. To say, I’d rather be a veiled threat than your version of a palatable Muslim woman.6

Chapter 1

Turkey Twizzlers and couscous on Sundays

English, Libyan, other

My mum called me down for dinner in that sing-song way she always did. But I was busy.

Nade-eine, dinner’s rea-dy – she called again, as I illustrated the hundredth perfectly placed eyelash and traced the curve of a nose on the two faces peering up at me from the pages of my sketchbook.

Dinner’s getting cold, sweetheart, she said, now in my room. A dab of blue eyeshadow here. A fringe there.

What are you drawing?

It’s me, Mummy.

Which one?

Both.

…

Come on, sweetie, let’s eat.

8I know what you’re thinking: this memory sounds made up. It’s just almost too convenient to be real. It too perfectly conveys the fragmented and fractured innards of my identity to sound like something a kid would actually do. But that’s why it’s real – because I really did view myself as two separate but simultaneous beings. I simply didn’t know how to be both.

One version of me had long flowing hair and bare shoulders, sometimes with a little star tattoo. This me had long lacquered lashes, cat eyeliner to rival Cleopatra’s and a Barbie doll pout. The other me had my head covered in an eclectically patterned scarf with a spherical face in a permanently chirpy smile. One was the English me and one was the Libyan me. On the brink of adulthood, I would become one, but I was never quite sure which one that would be. Like a caterpillar awaiting the chrysalis, I didn’t yet know what I’d emerge as.

Before becoming a visibly Muslim woman with an awareness of the heavy political implications of my existence, I was just a child with a foreign-sounding surname and skin that tanned easily. Growing up with an English, non-Muslim mother and a Libyan, Muslim father was like having two selves that lived parallel lives inside of me. These two sides of me barely met, and so they coexisted perfectly. Like flatmates who work opposite shifts, one sleeping whilst the other lives their life. Experiencing nothing of each other except some crumbs on the worktop 9and the scent of perfume lingering by the door. The eldest child in a mixed-race home has no blueprint for how to navigate life between two identities. I was making it up as I went along, and the way I dealt with it was to separate the fractions of my being along physical, geographical and temporal lines.

On weekdays, I was English. I wrote song lyrics up my arm and ate Turkey Twizzlers in front of The Simpsons (followed by The Weakest Link). I did my homework at the table and pretended I wasn’t listening to Hollyoaks in the background and spoke to my friends on MSN about who said what about whom. I wrapped my hair in socks so it would be curly for school and begged my mum to let me walk to the shop on my own for sweets. I listened to my iPod at the dinner table by hiding the earphones behind my hair and thought slamming my bedroom door in anger was the most grown-up thing in the world. I stayed up past my bedtime reading Harry Potter under my duvet and painted my nails a different colour on every finger.

Then, I was Libyan when we’d hurtle up the M1 every weekend to meet my dad’s old Libyan school friends in Coventry, Nottingham and Sheffield. I was Libyan when we’d eat stuffed peppers on kitchen floors, the lost cadence of Arabic washing over me as we listened to our dads rally against the dictatorship they had all fled – free in some terraced house in Earlsdon to say what would have got them killed at home – whilst our English mothers rolled their 10eyes and reminded them that they didn’t need to shout, they weren’t in Libya any more.

I was Libyan when we would eat couscous on Sundays, bejewelled with caramelised onions and chickpeas, tomatoey stewed meat and vegetables poured over the top. I was Libyan when my dad would lift us up and shake us whilst my mum hoovered up the small grains of couscous that fell beneath us, which we had inevitably got in between our toes and in our hair (couscous is a messy business when you’re a child). I was Libyan when my dad would get a sudden pang of homesickness and grow quiet for the day, looking out the window at our morose English street and imagining he was in the bustle of his home city, where the houses packed tight together like overgrown teeth in a teenager’s mouth and lines of washing ran between them like floss. I was Libyan when he’d take out his melancholy on the garage, randomly tidying up the leftovers of our lives into a semblance of order, watching our straight-lipped English neighbours avoid his eye as they slid into their houses and remembering how, at home, everyone knew everyone, how everyone’s door was open for a neighbour’s child to eat lunch or an old childhood friend to catch up over tea. I was Libyan when that sorrow would metamorphosise into a spontaneous desire to stuff sheep guts with spiced rice and meat, creating osbaan, a meal none of us were particularly keen on but that I ate anyway, eager to show him that home could be found here, too.

11In the winters, I was English. I would pop a small square of chocolate in my mouth every day in the month of December and count down the days until Christmas. I’d eat roast turkey on the 25th and unwrap my presents in front of the twinkling tree. I was English when I was singing Christmas hymns in school assemblies, my shiny tinsel earrings swinging in time with ‘Away in a Manger’. I was English as fireworks exploded in the air and as I made resolutions I’d break within a week. I was English in the rain and in the hail, in the grey din of a British January. I was English when we put on the local radio to listen out for our school listed amongst those closed for snow days. I was English in the spring, as everyone commented on how long the winter was and when warmer evenings suddenly felt full of hope. I was English writing Valentine’s cards to my friends and making nests for Easter chicks. I was English as the days got longer and our school trousers turned to checked summer dresses, as we laced together daisy chains and watched aeroplanes trace lines across the sky.

Then, suddenly, I was Libyan again, usually around the end of July. I don’t know exactly when it would happen, when and where the parts of me would do their silent exchange. She’s yours for the summer. See you again in September. Perhaps it was the last day of school, when I’d go home to the house turned upside down as we packed our lives into suitcases for the next six weeks. Maybe it was the first day of the summer holidays, when my parents, my younger 12brother and I would head out on the two-hour drive to Heathrow Airport. Inevitably running late and having forgotten something, we would rush down the motorway at breakneck speed, my dad’s driving getting increasingly erratic as the clock ticked closer to departure time, my mum berating him with her eyes. ‘We’re not in Libya yet!’ she’d tease, transporting us all to the lawless roads of Benghazi and the incessant beeping that sounded in every corner of the city, as constant and pervasive as birdsong. Or maybe it was in Heathrow itself, as I’d puke my guts out due to travel anxiety in the toilets whilst my parents solemnly watched the clock. It could be when we were on the rickety Libyan Arab Airlines plane, halfway across the ocean with England behind me and Libya on the horizon. Or as we landed, when the plane erupted in applause or when the hot gush of desert air smacked us in the face as we climbed down the stairs to the tarmac.

Either way, for the next month and a half, there was no balancing act. I’d eat with my hands, stay up too late and drink more Pepsi (Bebzi) than I’d ever be allowed at home. I’d sleep at a different auntie’s house every night, eat shawarmas and knock-off Nutella straight from the jar at 3 a.m. I watched horror movies on MBC and sang along to songs I didn’t understand the lyrics to. Everyone fasted until sunset and we broke our fasts on dates and milk as the mosques around the city reverberated with the word of God. We sat on the kitchen floor peeling almonds, stuffing courgettes, 13squeezing the juice out of tomatoes and chopping onions. Picking grapes straight from the vine and olives straight from the tree, we’d deliver them to neighbours armed with stock phrases I memorised beforehand. We’d float weightless in the hot salt bath of the Mediterranean Sea as the sun roasted our skin. Listening to the sounds of faraway crickets and the whoosh of ceaseless traffic, I’d dip freshly made bread in saccharine mint tea as my aunties gossiped about somebody’s son and somebody’s daughter.

Then, again, as abrupt as it had arrived at the helm of summer, the exchange would occur again. A plane would land on the grey London tarmac, serenaded by the familiar pitter-patter of rain, and we’d dig out the hoodies we had packed in our backpacks that we hadn’t needed for the best part of two months. The muted, brusque, clinical sound of the English language being spoken around me for the first time in six weeks would remind me that I was English again. At least, for now.

At first I thought it was a flaw in my character to slice myself up into separate parts. Other people didn’t struggle to see their mixed-race identities in such conflicted, tumultuous ways. Such people seemed to view it as the best of both worlds, whereas I felt marooned between two. Why was I overcomplicating it? But now I realise that this is a primary function of whiteness itself. Whiteness isn’t designed to be diluted; it cannot exist alongside anything else. In order for whiteness to be the preserve of privilege and 14power, it means that necessarily it must become tainted as soon as it is mixed with anything else. Whiteness with a drop of anything is no longer truly white. There is no such thing as being part white. I might be half English, my genealogy might be 50 per cent Anglo-Saxon, but the reality is that the brown in me negates the white. I never was and never will be half white, just like a person can never be half privileged, half powerful, half immune to the violence of the state. Half free from structural racism.

We have words for it these days. Terms that can explain away that feeling of being two halves instead of a whole. We call it code-switching. So rational, so detached a word to describe lacerating yourself into parts and deciding which is the most palatable for which audience, which you is acceptable for this context. Code-switching is often construed as empowering – getting ahead of the current, learning to navigate structural prejudices, to take charge of your othering. But code-switching itself confirms that we must live our lives by codes, by rules, by standards and by norms. That we must conform fully at any one time. We have no language for being more than one thing at once. We only know and we are only taught how to switch, to slot ourselves in, to constantly, constantly please.

Now, I can look back at my childhood and see that I wasn’t ever really one thing or another at any given point. I was perpetually a half thing – not quite complete. It’s little wonder I was hit with a midlife-crisis level of introspection 15before I was barely through puberty. They may have been only glimpses, but the other me was always there whilst I inhabited whichever version my environment called for. My foreignness was a spectre in the distance that emerged as I was eating dinner with my white grandparents, growing closer as they pointedly served us chicken whilst they ate pork and made comments about it being such a shame we can’t have a bite of sausage. It was there when people overcomplicated my straightforward name and asked me where I was really – no, really – from. It grew larger when I’d have to explain that I couldn’t sleep over at my friends’ houses for the fiftieth time because it was ‘against my dad’s religion’ (which I had presumed it must be, down to the steadfastness with which my parents stuck to this rule). It was there, it was always there, forming a ball of alienation and confusion in the depths of my stomach.

The opposite was true, too. My whiteness lingered threateningly in the periphery as I struggled to converse with my Libyan cousins; my fumbled, stunted Arabic a reminder that I wasn’t a proper Libyan and my strange English habits outing me as unavoidably different there, too. I gave everything to fitting in every summer when we went to Libya. I’d hate it when my cousins wanted to practise their English on me or refer to me as their English cousin to their friends. I was jealous of how utterly at ease with their Libyanness they were. How they knew the nuances of language, culture and habit that only a native can pick 16up. I was embarrassed of my ungainly, uncontainable Englishness – the way I pronounced certain words and how I didn’t know the right thing to say at the right time or know how to eat aseeda (a giant mound of dough covered in date molasses) with my hands or suck the bone marrow out of a piece of meat. Even now, as an adult, I am ashamed of how I have to rehearse a conversation with my dad before wishing a cousin congratulations on their engagement, how I don’t innately know the right phrase to say when someone has passed away, how after the birth of my son, my aunties showered me with the most intricate, eloquent blessings and wishes and all I could muster was shukran, shukran. Thank you, thank you.

I talk a lot about how my visible Muslimness is what ejected me from whiteness, but in truth, a nation like Britain pounces on any semblance of weakness as soon as it can sniff it out, othering and segregating long before our adult selves are aware of what is befalling us. The veneer of whiteness soon shatters for those who don’t rightfully deserve it, for those who don’t truly succumb to its regimented demands. It was already dwindling when I was a nonwhite toddler in the arms of my clearly white mother and people looked at her with judgement. It was bursting at its seams when I explained to the dinner ladies at school that I couldn’t eat pork because my dad was Libyan (that’s what I thought the reason was) and they looked at me like I had just calmly informed them that I was an alien. Whiteness 17was long gone by the time my friends were sneaking sips of decades-old alcohol taken from the back of the kitchen cupboard and calling me boring for faking a stomach ache to go home. Even when I thought I belonged, I didn’t. Even when I held whiteness in my hand, it was already slipping through the cracks of my fingers.

Like all children do, I learned how to be a person through watching my parents. Except my personhood was separated into two people who represented each half of me. When I consider how I came to think of my identity later on, I realise it’s no coincidence that my parents viewed each other’s homelands with derision and even scorn. My mum had lived in Libya for five years before I was born and made it clear she wasn’t willing to repeat that experience in a hurry. My dad had grown resentful from decades of languishing in England when his heart yearned to return home, which he would have done long ago if it wasn’t for his now-British family keeping him here. Despite their union having created me, I never saw a way that Englishness and Libyanness could exist in harmony – and certainly not within me – because my parents seemed bound together only in spite of their divergent backgrounds and never because of them.

This book explores much of the after – how the hijab changed everything for me and what happened to my sense of self after being well and truly otherised for good. But for there to be an after, there must be a before, and that was as fiercely personal as it was political.

18Growing up, I was a daddy’s girl and by that I mean that I have always felt the pangs of my father’s heart twinned in perfect sync with my own. From childhood, I could interpret the frown lines and understand the sighs. I saw the crumpled wax-paper hands from the hours of manual labour and could read in them the sacrifice and the silent, swallowed pain. I knew, innately, that as the firstborn child, my birth had changed the course of my parents’ lives, that my dad was here in this country he loathed because of – and for – me. I felt not obliged but compelled to show him that glimmers of home could be found here, too, knowing it would cheer him up if I paid special attention in one of his impromptu Arabic lessons at the dining table or stayed to speak to whichever relative he was on the phone to when everyone else invented an urgent reason to leave the room.

At the same time, I was a pre-teen who clashed with her mother like every girl has in the history of the universe. I was painfully aware that I wasn’t like her, that I wasn’t going to inhabit the same spheres of womanhood that she dwelled in. I was chubby and she was thin, she was white and I was… something else, whatever that was. She fulfilled society’s standards of what it means to be white, to be a woman, and I already knew I didn’t. My fierce love for her as my mother collided with a secret hidden anger: I almost blamed her, inexplicably, because it was her womb that had spawned this two-sided existence that didn’t make sense to me. I envied her for being so sure about who she was 19when I couldn’t find that out myself and for having grown up without the weight of racism weighing down upon her. I imagined her as the homely Libyan mother that my aunties were, who spent their days making pasta from scratch and cleaning the bathrooms, dishing up extravagant dishes three times a day and most of all passing on genes to their children that make them one thing rather than two.

I associated my mother with my Englishness and with my whiteness because, after all, it came from her. And so, the more I was socially and politically maligned by the racism I was increasingly experiencing, the more distant I felt from the woman who had saddled me with this hotchpotch identity to begin with. I felt bitter, as though it would have been easier if I didn’t have any whiteness in me to try to belong to in the first place. Likewise, the more I was racialised in public and the more I was outcasted from the white spaces I had once inhabited with ease, the more I began to identify with my dad and with his culture, even if that wasn’t the sum of all my parts. As the Arab Spring dawned, this became a vehicle into my Libyanness that I had never been given before. I may not have understood all the social cues and nuances of language as a ‘real’ Libyan, but I could become an expert on the politics and, ironically, my free access to social media in the west meant that I could know even more than my family on the ground. I became obsessed with the Arab Spring and the subsequent political conflicts in Libya. I pinned Libya’s new freedom 20flag to my school uniform and spent my lunchtimes on Twitter following every latest development. I shared so much, and with such detail and urgency, on my newly created Twitter account that I even had western journalists contacting me for interview because they thought I was a rebel fighter on the front lines and not a schoolgirl from the Midlands. But like all politics, it was fleeting. Gaddafi was overthrown and Libya descended into a power vacuum and was plunged into civil war, and my GCSEs came and went and I no longer knew everything that was happening. The instability in the country, as well as a spate of kidnapping of foreign nationals, meant that my dad no longer thought it was safe for us to visit, and then all at once my summers were no longer spent in a place where the air thickened like treacle but in the solemn malaise of England. And then, again, Libyanness, like Englishness, was a part of my identity that may have been bound to my DNA but felt further away than ever.

Whilst the geographical core of my whiteness was here in the UK, much of what I was latently learning about whiteness came from my time in Libya. Privilege, after all, manifests as a blindfold to those it is endowed upon. Like many formerly colonised lands, Libyan society is obsessed with light skin. Women wear gloves so their hands don’t turn brown whilst driving. Teenage girls avoid the sun at midday lest their skin become anything but milky. Women with the whitest skin have the best prospects, the best chance 21of marrying into a reputable family. Bleaching creams are applied daily like moisturiser. A white-skinned woman at a wedding will find herself flogged by multiple mothers of eligible bachelors who already see visions of their future white grandchildren reflected in her complexion.

I remember laying down to sleep next to my cousins one night – the way we always did, on fraash mattresses spread out on the floor in my auntie’s sprawling marbo’a (a room built for guests). We’d been to a wedding and we traced the henna on our hands, hummed the songs whose volume still pounded in our chests and dreamed of ourselves as brides. My youngest cousin turned to me and said, ‘You’re lucky, you’ll be able to marry a nice man,’ and when I asked ‘Why?’ she said, ‘Because you’re white.’

‘I’ll get someone old or mean,’ she added. We were eleven.

The funny thing is, I didn’t think I was white. Skin-tone-wise, I was at my darkest, having baked in the hot Mediterranean sun for the past six weeks. Identity-wise, I knew I wasn’t white either. I had watched enough eyes dart between my grandparents and this brown-ish child inexplicably calling them Nanny and Grandad to know that people didn’t see us as the same.

What my cousin had meant, of course, was that I had more proximity to whiteness and by default more access to the privilege it promises. I couldn’t see it at the time, but the way my aunties always berated me for letting myself get 22so brown in the sun, how some of my cousins delighted that they were now whiter than me – even how they said that I should have got my mother’s blue eyes instead of my brother (as though I had a choice in the matter) – was because they saw whiteness for what it was. It is something that can be given or denied, something that must be earned and maintained. Something delicate and ephemeral, something ravenous for constant upkeep, something that can be lost in an instant if it isn’t preserved. Like milk, something that curdles as soon as anything else infiltrates it. Something that goes bad in the sun.

Chapter 2

Blood, bone and chiffon

How the hijab changed everything

The glint in his eye tells me he pledged his allegiance to defending the borders of Great Britain roughly around the same time he exited the womb.

He informs me that I have been selected for random additional screening, gesturing in wild circles around my head to indicate that the cause for this absolutely random screening is the shiny blue hijab I’m wearing.

‘Take a step to the side for me, please.’ Curtness reveals the spiky edges of his voice.

Up to this point in my fourteen years of life, I had regarded people in authority as trustworthy, with noble and caring intentions, if a little pernickety about rules like finishing your homework and going to bed on time. But this was different. For the first time, I was being perceived as a 24threat – a thing to be handled with suspicion and derision. Inside, I felt wrong: a hot sensation of shame and self-contempt. The beeping and clattering, talking and whirring of the people and the airport machinery around me grew jaded, as it was drowned out by the fierce gush of my own pulse in my ears.

I wait by the side as instructed and I lock eyes with my younger brother who has already passed through the metal detector entirely uneventfully, without so much as a second glance from anyone. He raises his eyebrows and I shrug in reply. I’m glad we are too far apart to speak. How do I convey what is happening, this thing morphing between us that I cannot name?

I am taken to a small windowless room where a woman sizes me up with beady, excessively lined eyes. There’s another detector, this time an entire booth, and she explains that I’ll have to stand in it whilst it X-rays me. I picture cameras burrowing down to the marrow of my bones, checking if there’s a suspicious package concealed in my platelets.

‘Please remove the head dress, love.’

It takes me a moment to realise what she means by ‘head dress’.

I set about unwrapping my scarf, which is no easy feat given that barely a fortnight into wearing the hijab, I am still at the stage of relying on no fewer than ten pins and a 25whole lot of luck to keep it in place. She watches my quivering hands search for the exact location of each pin, a bemused smirk curling her dry lips at the edges.

After what feels like a year, I’ve managed to unwrap one layer. ‘Nearly there,’ I reassure her, with a nervous and hollow laugh. She purses her lips and asks to see my passport. Taking a seat, she throws her legs ostentatiously onto a small plastic table, folding one over the other, browsing my passport like it’s this morning’s tabloid paper.

‘Nay-deen,’ she starts, mispronouncing my name as most people do. ‘Ash… as… az… barley?’

Naydeen Azbarley – easy first name, confusing surname. Half familiar, half foreign. My oxymoronic identity summed up within my name itself.

‘Where you coming from, then?’

‘Benghazi… uh, Libya.’

‘Lebanon?’ she says.

‘Umm, no, Libya.’

She regards me as though I informed her I’d just returned from a colony on the moon.

‘My dad’s from there,’ I explain.

She looks at my passport and back to me again, taking in the stark difference between the child in the photo and the slightly older child in front of her who looks decidedly more foreign.

Finally having unwrapped my scarf, she signals for me 26to turn around in a circle like some sort of bleak fashion show as she inspects my scalp, pulling my bun side to side, up and down.

‘How come you bother with that, then?’ she asks, ushering me into the 3D scanner.

‘Well,’ I begin, before realising that I don’t quite know what to say. Nobody has yet asked me that question.

When I think back to this encounter at the airport, I realise that something significant and concrete occurred in that moment. A shift – in me, in my family, in how we define ourselves and how we are perceived in the eyes of others. When my brother and I, who share the exact same set of parents, were separated – him going through security without so much as a second glance, and me, set aside for questioning, for scrutiny – I realise that what I am witnessing is the making of who I am and the breaking of who I was.

They may not have realised it, but these border staff made a decision in that moment that would define me for life. Or maybe that was what they intended to do all along.