Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Johnny Henderson spent four years during the Second World War as aide-de-camp to one of Britain's most famous soldiers of the twentieth century, General Bernard Montgomery – or 'Monty', as he was popularly known. Shortly before he died in 2003, Henderson wrote about his time with Monty at Tac HQ. In Watching Monty, his account takes the form of a series of insightful anecdotes and brief pen sketches that give a fascinating and often humorous window on life with Monty and those with whom he worked, or came into contact, during the war years. These people range from King George VI, Winston Churchill and Sir Alan Brooke to Eisenhower and the German surrender delegation on Lüneburg Heath. Drawing on his own private photograph albums and the photographic collections of the Imperial War Museum, Johnny Henderson relates his time as Monty's ADC, from the Western Desert to Berlin, in the form of a photographic anecdotal scrap book. His pithy observations of life at Tac HQ make a unique contribution to our understanding of what made Monty tick, and shows us a less well-known but lighter side of the great man.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 179

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

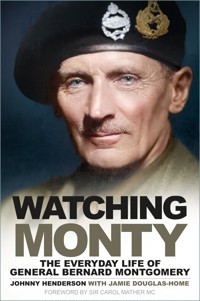

Cover illustrations. Front: General Bernard Montgomery. (Illustrated London News) Back: The author and Monty surrounded by French citizens at Caen Cathedral. (Eton College Library)

First published 2005

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

In association with the Imperial War Museum

Text © The Estate of J.R. Henderson, Jamie Douglas-Home, 2005, 2024

Imperial War Museum photographs © The Imperial War Museum, 2005, 2024

The right of The Estate of J.R. Henderson and Jamie Douglas-Home to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75249 576 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Prologue

Introduction

1 With the Eighth Army in the Desert

2 Storming Sicily

3 Assault on Italy

4 Planning for ‘Overlord’

5 The Battle of Normandy

6 Thrust into Germany

7 The Challenges of Peace

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

BY SIR CAROL MATHER MC

I first met Johnny Henderson at Monty’s Tac HQ immediately after the victorious Battle of Alamein. I was acting as Monty’s liaison officer; Johnny had arrived as his new ADC. But the roles were interchangeable. Henderson, although a young officer, was an experienced desert hand. I was sure he would be okay. So I showed him into his bivvy tent and left. I was departing for an ill-fated SAS raid behind the lines.

I was not to see him again for the best part of a year. After I had been captured and taken prisoner of war, I made a beeline for Monty’s Tac HQ following a lucky escape through enemy lines in Southern Italy. Monty was away. Johnny was in charge and put my companion and myself to sleep in Monty’s caravans. What a contrast from the moaning of the oxen in some godforsaken barn a few nights earlier. Once the invasion of Europe began, I was invited to rejoin Montgomery in my former role. Henderson was by now his longstanding ADC.

It was like old times serving at Monty’s Tac HQ. One was right at the heart of the action; contrary to the usual perception, he was a very relaxed and easy master, but only if he trusted you. If he did not, you were out. Of course, he had a ruthless streak, particularly with officers, of whatever rank, whom he considered ‘useless’. He liked to relax in the company of his young staff, as Johnny’s memoirs make clear, and, in the mess, was always goading them to admit youthful indiscretions. But no cheekiness in return was expected! I cannot imagine a happier atmosphere at any similar command post. And his use of liaison officers was a touch of brilliance. But Monty was inclined to be jealous or dismissive when it came to his army contemporaries. The exceptions being his own army and corps commanders and, of course, Brooke and Alexander.

Johnny’s rapport with Monty played a little known but crucial part in the winning of the war; for here was someone upon whose absolute loyalty he could depend and who was also an agreeable companion (Monty tolerated Johnny’s somewhat impish sense of humour). Whatever the location – in the deserts of North Africa, across the Italian plains and mountains, in Normandy, or even on Lüneburg Heath at the time of the Surrender – Johnny, as his aide, laid out Monty’s little tented camp, exactly as it had been at Alamein. It is not sour grapes to recall that American generals opted for the largest château available!

I am glad that Johnny Henderson finally decided to tell his side of the story, for it is laced with humour. On many occasions he can be seen to be skating on very thin ice, but, when found out, Monty took it in very good part. What these pages reveal is the human face of war: both of a great commander, and of his shrewd but modest ADC. A double act, if you like, but a very good one.

PROLOGUE

When I left Monty in 1946 after being his ADC for nearly four years, he said, ‘Johnny, you must never write a book.’ Then he added, ‘Anyhow, you are not capable of it.’ Actually I have never before been inclined to do so. But now, some sixty years later, I have decided to tell some stories of my time with Monty before it is too late. I do so at the suggestion of a few friends. Perhaps it is presumptive to refer to my efforts as a book!

Memory is kind. It tends to recall the more amusing times and forget so many of the long, drearier days and some of the more alarming moments. Monty’s brilliant military exploits and his great battles have been extensively documented. So I hope my reminiscences will give an idea of the less well-known but lighter side of Monty’s Tac HQ (Tactical Headquarters) and the relaxed atmosphere in which we lived. I have also included many photographs from personal albums that I put together at the time.

As I am nearly the only fellow still around who was close to Monty at the time, I have given interviews to two German television stations recently. They asked me if I saluted every time I saw Monty and if I always called him ‘Sir’. I replied that I did not think I had ever saluted him and that, after the first week or so, I never called him ‘Sir’ again. They could hardly believe their ears and were amazed to learn that life with Monty was nothing like as austere as they had previously thought.

I left Eton in the beginning of 1939 and was just about to go up to Cambridge to study history at Trinity when war was declared. I was at the university for a year, but it was an unsatisfactory time, as everyone wanted to get off to the war and one never really knew if one would be going back for the next term or not.

In the summer of 1940, while I was waiting to join the Coldstream Guards, I happened to go back to Eton for the Fourth of June celebrations and met an old friend, Kenneth Inchcape, who had just got back from Dunkirk. Kenneth said, ‘Why don’t you join a cavalry regiment instead and come to my lot, the 12th Lancers?’ The idea rather appealed to me, so Kenneth promised that he would sound out the colonel. He must have given me a reasonable reference because I soon heard that the 12th Royal Lancers had accepted me. Then I was called up the following week.

I went to Farnborough as a private soldier to learn the ropes for about a month and then moved on to Sandhurst to be trained as an officer. Four months later I joined my new regiment, which was based near Horsham in Sussex, preparing for a possible invasion.

I had been there nearly a year when we heard that we were going to be sent to the war in Egypt. In late 1941 we set sail in the last ship in a large convoy. I remember we had to sleep in our lifejackets because the U-boats were on the prowl.

Eventually we got round the Cape and disembarked in Durban on 3 November. After two weeks or so there, we were transferred to another ship, The New Amsterdam, which was reputed to go much faster than the enemy submarines. I believe there were something like 22,000 troops on her. Therefore we had to take turns in the hammocks, as there was not enough room for everyone to sleep at the same time. It was very hot and uncomfortable, but the ship only took three or four days to get up to the Suez Canal.

We stayed near Cairo to start with and were sent out to join the battle in the desert in December 1941. Auchinleck’s front line was then deep into Libya, but we were soon forced to retreat. Rommel gradually pushed us further and further back and, by July 1942, the enemy was only 60 miles or so from Alexandria.

For some reason I was able to find my way around the desert using a sun compass. So, around that time, I was chosen to take a convoy of three armoured cars and five supply vehicles to see if we could get across the Qattara Depression, a large and virtually uncharted area of salt lakes and marshes about 30 miles south of Alamein. The idea was to find out if the enemy could creep through the depression and then launch a surprise attack on the Alamein line of defences.

It soon became clear that a large force would have no hope of completing such a task. Our vehicles were only able to travel a short distance of two or three hundred yards before one would invariably break the thick salt crust that covered the bog and get stuck. We would then dig it out and continue on our way. It was a tiresome process, but in the end we managed to cross the marshes and, a little further on, we came upon a narrow path leading up a steep escarpment.

Monty’s Tac HQ camp in the desert. (Eton College Library)

As we were now a long way behind enemy lines, I told the drivers of the vehicles to wait while I took my jeep up the path to explore.

I had not gone very far when I spotted a German tank coming towards me with some of its crew lying, sunbathing, on the top. Luckily, I found a spot wide enough to turn the jeep round, and, hooting my horn continuously to warn the others at the bottom, set off down the track with the tank in hot pursuit. They fired at us as if we were running rabbits, as we dispersed and rushed off into the desert.

Somehow we lost our pursuers, and when the convoy met up again we were delighted to discover that we had all emerged from the desperate chase unharmed. We then drove back over the marshes, using our old tracks to avoid getting stuck. As we could only move by night because German planes were out searching for us during the hours of daylight, it took a long time to get home. Indeed, when we arrived safely at our base, we had been away for two weeks.

A few months later my regiment fought on the southern flank during the famous battle of Alamein. Then, on 10 November 1942, less than a week after Monty’s great victory, this rather surprised and extremely nervous captain of only 22 years old was summoned to join the triumphant Eighth Army commander’s personal staff. I have always thought that the main reason why I got the job was because I managed to plot a course through those treacherous marshes twice.

Monty learned early on that I had no ambitions to be a regular soldier after the war. One night at dinner in the desert he asked me what I thought of a pamphlet he had written on army leadership. When I said that I had not read it, he exclaimed, ‘Oh Johnny, you will never make a soldier.’ ‘You are quite right,’ I replied, ‘and, anyhow, I don’t want to be one.’ ‘So what do you want to do?’ he asked. When I said I wished to go into the City, Monty retorted, ‘Oh, that’s no good. All they want to do is make lots of money and put the dates of Ascot, Wimbledon and the start of the grouse shooting season into their diaries!’ ‘That,’ I answered, ‘is just what I want.’

Funnily enough, after I left the Army, my life panned out almost exactly as Monty had predicted. I had a long career in the City and racing and shooting became two of my favourite hobbies. But I still remained in close touch with my old chief, who kindly agreed to be godfather to my elder son, Nicky, and always used to come to lunch at our home near Newbury on the Sunday before Christmas.

INTRODUCTION

Lieutenant-General Bernard Law Montgomery, later Field-Marshal Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, was three months short of his 55th birthday when he set foot in Egypt in August 1942 as the new commander of the Eighth Army. I joined this remarkable individual that November and stayed with him for nearly four years. During that time I had practically every meal with Monty and lived with him day in day out. Therefore I saw every side of his character.

Monty was the most even-tempered person one could imagine. He hardly ever showed any emotion – not even on the morning of the Normandy landings or when he first heard that a German contingent was coming to surrender. About the only time I ever saw him agitated was in the early hours of 8 June 1944 (or D-Day +2 as it is also known) off the Normandy beaches when he told me to ask the captain of the destroyer, which had brought us over, to go in closer. He wanted to get ashore urgently and was upset when the boat shuddered as it hit the reef and it became clear that it could go no further.

Monty was a person who always wanted to be in command – yes, always. He made his opinions quite clear by repeating himself. He would listen on occasions to others, particularly his Chief of Staff, Freddie de Guingand, and his Head of Intelligence, Bill Williams. But, if something they had said changed his mind, he always claimed their ideas as if they were his own. I never heard Monty admit that he was wrong.

I have often been asked if he had a warm side. Yes, he did, but he was reluctant to show it. In the four years I was with him I never once heard him mention his wife, who had died just before the war. However, he was very proud of his son, David, and was always anxious to do for him what he felt was right. But, strangely, he also seemed to be jealous of anyone else giving David a good time.

Monty ended up with very few close personal friends after the war. He seemed unable to unwind outside Army circles. Sir Alan Herbert, the brilliant comic writer and MP for Oxford University, was a good friend of Monty and his wife, Betty, who knew many people in the world of the arts. Monty would ask A.P.H. out to Germany or Holland and his visits were the greatest fun for us. I remember in Luxembourg at the end of the war we had to find a piano for A.P.H. to play. Monty certainly enjoyed his performance. Monty was also close to another distinguished Oxford academic, the military historian, Professor Cyril Falls. Another true friend in peacetime was P.J. Grigg (Sir James Grigg, the Secretary of State for War during the war). But I cannot name another close confidant, who was not in the Army.

Bill Williams was once asked if Monty was a nice man. He replied, ‘Nice men don’t win wars.’ That may be true but I thought Bill was being a little hard. Monty had a pleasant, straightforward sense of humour and liked the ridiculous. Although he did not much like humour against himself, he often told the following tale: when he was a colonel in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in Egypt before the war, one of his young officers was permanently out with women and consequently too tired to be of service. So Monty got hold of the lad and said, ‘I am giving you an order that you are not to go to bed with another woman without my permission, but in no circumstances must you be afraid to ask. See?’

Shortly afterwards, Monty was asked to dinner with the British Ambassador in Cairo. During dinner, the butler approached the Ambassador, bowed and said, ‘There is a telephone call for Colonel Montgomery.’ ‘Ask who it is,’ the Ambassador replied, ‘and what he wants.’ The butler soon returned: ‘It is Lieutenant so and so asking his colonel if he can have a woman.’ ‘One woman once and back by ten’ was Monty’s curt reply.

Monty also had the ability to develop a clear picture of the most difficult situations. For instance, when his son got engaged, he was abroad, so he asked his father to take his fiancée to buy a ring. Monty realised that things could become tricky if she picked an item that was more expensive than David’s budget of £250, so he visited a jeweller the day before his planned rendezvous with David’s intended and told him to put all the rings worth £250 or below on to a single tray. It was then arranged that when Monty returned the next day with a pretty girl and asked to see his engagement rings, the jeweller would bring out the tray, saying it contained his complete collection. Monty could then be absolutely certain that a ring that was too dear would not be chosen!

Nigel Hamilton, who wrote a three-volume biography of Monty, suggested he was a repressed homosexual. I can truthfully say that such a thought never crossed my mind in the four years I was with him. Furthermore, if rumours had been circulating then, Monty’s reputation would have been harmed and his credibility completely undermined. I can also swear that such a scenario never occurred. Hamilton says that he surrounded himself with young officers, but so did all his colleagues. Leese employed Ian Calvorcoressi, and Horrocks, Harold Young, as their ADCs, but nobody ever suggested those generals had homosexual tendencies. Monty wanted to command and it was much easier to order the young about. Moreover, his only relaxation was to have an argument at dinner each night – he could never have done that with a bunch of oldies!

Monty. (Imperial War Museum [IWM] TR1035)

I have also been asked if he was religious. Monty always had a Bible by his bedside, but I would not know how often he opened it. He would quite often say, ‘Get on to Padre Hughes and tell him we want a service on Sunday. Not too long though.’ We also had a wonderful Army chaplain in Europe whom Monty chose. So I suppose religion played a part in his life.

Monty did not much care what he ate, never drank alcohol, except a toast, but he never minded us having a dram. Before he left Germany to return to England to be Chief of the Imperial General Staff, he heard us saying that we might as well divide what bottles there were in the mess and take them back. He firmly reminded us, ‘I am a member of this mess as much as any of you and I want my share.’

He was never concerned about what clothes he wore. In the desert, like everyone else, he would turn out in khaki shorts or trousers and an open-neck shirt. In Europe, he favoured corduroy trousers and a grey jersey. Even when Winston Churchill came he was seldom seen in uniform.

I have often been asked if I was fond of Monty. ‘Fond’ is a difficult word, and, in the past, I have never been able to answer yes or no. On reflection, I suppose that it would be unlikely for a 22–26-year-old, as I was then, to be fond of such a person. Yet, after all these years and having read what I have written, I think that I need no longer sit on the fence. I am now prepared to say that I was fond of this extraordinary character.

ONE

WITH THE EIGHTH ARMY IN THE DESERT

NOVEMBER 1942–JUNE 1943

When I joined Monty’s Tac HQ, the Eighth Army was chasing Rommel’s retreating forces into Libya and the Allied invasion of Morocco and Algeria under Eisenhower had just begun. So the depleted German and Italian Army was now facing a war on two fronts.

The Libyan port of Tobruk was recaptured on 12 November 1942. Then Monty won an important victory on 17 December at El Agheila on the coast road in between Benghazi and Tripoli, where some Eighth Army soldiers had been twice before. Monty then prepared to advance on Tripoli. We entered the Libyan capital on 23 January 1943 and stayed there for a few weeks to open up the harbour and build up our supplies for the next stage of the journey towards Tunis.