Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

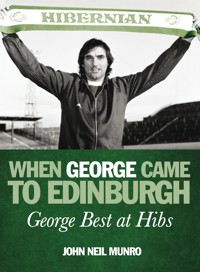

Played 24, won 10, lost 10 and drawn four. Three goals, three benders, one suspension and one sacking. This is the inside story of what happened when the world's most famous footballer joined the tenth best team in Scotland. In the winter of 1979 Hibs were enduring a season from hell and were freefalling towards relegation. They needed a miracle man to save them - what they got was a lonely, depressed man caught in a downwards alcoholic spiral. In just under a year in Edinburgh, George Best was never off the front and back pages of the national newspapers. A scrupulous, moving, extraordinary account, John Neil Munro weaves together an absorbing and unique portrait of a lost icon, with insights from his widow, his team-mates, his drinking buddies and many of the fans who saw his great performances; this is the definitive story of what happened when George Best came to Edinburgh.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 270

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WHEN

GEORGE

CAME TO EDINBURGH

This eBook edition published in 2013 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2010 by Birlinn Limited

Copyright © John Neil Munro

The moral right of John Neil Munro to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84158-889-6 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-588-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This book is dedicated to the friends who gave it encouragement, especially DJ Murray and Spook.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1GENIUS

2JOURNEYMEN

3THE SEASON FROM HELL

4GEORGE SIGNS FOR HIBS

5TWO DEBUTS

6OFF THE WAGON

7SUSPENDED

8SACKED

9‘THE TROUBLE WITH GEORGE IS . . . ’

10ONE LAST CHANCE

11RELEGATION

12FIRST DIVISION

13POSTSCRIPT

14MEMORIES OF GEORGE

APPENDIX – GEORGE BEST FIRST-TEAM APPEARANCES FOR HIBS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

On the morning of Saturday, 10 November 1979, the people of Edinburgh woke to stories in their local newspaper of strange goings-on. Pride of place on the front page of the Evening News went to the peculiar tale of a 61-year-old forestry worker who had complained of being assaulted and threatened with abduction by ‘strange creatures’ in a dense wooded area near the town of Livingston. The man – who baffled detectives stressed was sober, of sound mind and impeccable integrity – told a tale that was as chilling as it was inexplicable.

While walking through the woods, he came across a 30-foot high spacecraft with a dome that constantly changed colours atop a platform with antennae. He was then attacked by two ‘aliens’ – with round bodies and at least six legs – which bore no resemblance to humans. They approached him silently and at great speed and made genuine efforts to drag him into the machine. The man told police that he became aware of a foul smell, promptly fainted and woke to find that the aliens had disappeared and that he had lost his voice and couldn’t walk. He then had to crawl one-and-a-half miles to his home, from where he was subsequently taken to Bangour General Hospital.

At the site of the ‘abduction’, police found marks on the ground where leg struts of some machine weighing several tons had rested. The grass was pressed down in two parallel ladder-like patterns and there were four holes sunk deep into the soil indicating four supporting struts. It was generally agreed that no land-based machines that size could have penetrated so deeply into the forest and the marks did not bear resemblance to any land or airborne vehicle known to man.

It isn’t known if the victim of the abduction attempt was a Hibernian fan, but you kind of hope he wasn’t. Because if, after checking himself out of hospital, he had gone to Easter Road that Saturday, he would have seen another strange sight which would have added to his confusion. Striding along through the winter gloom that seemed to hang permanently over the old stadium in those days, past the Albion Road sauna and surrounded by a swarm of camera-wielding press hacks, was certainly the most glamorous and debatably the greatest-ever footballer to grace the game. And to make it even stranger, George Best, arm-in-arm with his gorgeous wife Angie, wasn’t just making a social visit to the struggling Leith club. No, he was actually just about to discuss signing a contract that would see the most famous footballer of all time play for Hibs!

The coming together of George Best and Hibernian FC was one of the more bizarre episodes in the history of Scotland’s national game. True, it’s not quite as implausible as Dumbarton’s brave but ultimately hopeless bid to sign the Dutch genius Johann Cruyff in 1980, but it comes close. Thirty years on, it still raises questions. Why did a man who could have played anywhere in the world choose to come to Scotland? And why did he decide to sign for Hibs, who were statistically only the tenth best team in the land in 1979, when the wise money would have been on him playing for Celtic or Rangers, the two clubs who had dominated the Scottish game for most of the twentieth century? And once he signed, what went wrong? How did he end up getting suspended and then sacked by Hibs? How did George blow the final chance to resurrect his career and to achieve one of his great ambitions – to perform on the biggest stage of all and play at a World Cup? Hopefully, this book will answer these questions and also correct a few of the myths that surround George’s time in Edinburgh.

Hibs have been habitual underachievers, but that particular year they were experiencing a season from hell. Rooted at the foot of the table after one-third of the season, they needed a miracle worker. Instead, they signed a depressed, lonely, faded superstar who was fighting a losing battle with alcoholism.

In the many books written about Best, there’s been very little mention of his Edinburgh episode, and the cynics will probably say that the biographers have got it right. They’ll argue that he only played a handful of games, only scored a few goals and failed to save Hibs from relegation. But the cynics are wrong. In the end, George was a Hibs player for just 36 days short of a year and he even came back the next season to play for Hibs in the old First Division. And although he may have been a shadow of his former self, he still managed to conjure up moments of breathtaking brilliance. If he had spent the year at either of the Old Firm teams, you would never have heard the end of it and his stay would have been the subject of countless books, stage plays and possibly even a light opera. But because he played with Hibs, his year tends to be belittled and passed over.

Looking back on George’s time in Edinburgh, sometimes you don’t know whether to laugh or cry at what he got up to. On the one hand, his drinking and womanising have elevated George to patron saint of the lad culture, but it should never be forgotten that his alcoholism caused a great deal of grief to those who loved him most. So in retelling the story of his year in Scotland, this book will try to avoid glorifying or being judgemental about his exploits. Instead, it is a straight narrative of what actually happened through the recollections of George, Angie and more than 20 people who played with him, drank with him or just stood on the terraces to watch him play.

Another rich source of information was the newspapers of the time. Whatever his personal problems, George could still play the press like no one else. There was a time in early 1980 when it seemed that every day the national newspapers carried a photo – usually on the front page – of a pensive-looking George at Edinburgh or London airport having just been sacked or suspended. All the big-selling dailies and Sundays boasted regular ‘exclusive’ photos and stories with the star. The Daily Express, back in the day when it led the middle market newspapers, had a weekly Monday column where George offered his personal views on his own frailties.

Special thanks go to Angie Best for taking time to answer all my questions and to all those who gave their memories of meeting George or of seeing him play. Thanks also to those who couldn’t help, but knew a man who could. I’m thinking of the likes of Stephen Rafferty, Rab McNeil of The Herald, Sandie McIver (Edinburgh) and Norrie Muir, and to Ally Clark and Callum Ian MacMillan for their help. Gratitude goes, too, to Neville Moir, Peter Burns and all the rest of the Birlinn team, Richie Wilson my editor, Kate Pool from the Society of Authors, and staff at Stornoway Library, the National Library of Scotland and the British Library Newspaper Reading Room (Colindale, London).

GGTTH

John Neil, February 2010

CHAPTER ONE

GENIUS

George Best always wanted to be remembered for his football abilities rather than his off-the-field activities. So before describing the occasional madness and sadness of his year in Edinburgh, it’s only right to recall that at his peak in the mid-1960s, George was an awesome football player. The boy from Burren Way on the Cregagh Estate in Belfast had it all. Equally strong on either foot, he was beautifully balanced and lightning fast, with an ability to deliver pinpoint passes from all angles and distances. He had tantalising ball control, possessed a body swerve that could destroy opposing defences and could shoot crisply and accurately from any distance. Best was also a strong and fearless tackler; indeed Old Trafford boss Sir Matt Busby always said that George was the best tackler in his great Manchester United team of the 1960s – and this in a side that featured pitbulls like Nobby Stiles and Pat Crerand. To round things off, George was also good in the air and pretty handy in front of goal, scoring 178 times in 464 appearances for United. The sight of George lacerating a defence is one that will always stick in the memory. Best’s favourite football writer, Geoffrey Green of The Times, got it right when he once memorably described George, aged just 19, ‘gliding like a dark ghost’ past Benfica defenders in a 1966 European Cup tie.

George’s football talent was spotted at an early age by Bob Bishop, Manchester United’s chief scout in Northern Ireland, who famously sent a telegram to Busby which read: ‘I think I’ve found you a genius.’ George overcame doubts about his slight frame and his own homesickness to sign as a professional for United on £17 a week in 1963. The teenage starlet was obsessed with football and dedicated to his craft; he loved to train and to help those around him. George claimed that – as a callow teenager – he could beat his teammates in training sprints running backwards, while they ran forwards! Rigorous workouts helped build up his weight to 10 stone 3lbs, which was to remain fairly constant throughout his glory days at Old Trafford. George was also, as even the most heterosexual male would have to admit, a very handsome man. With his athletic build, boyish good looks, shock of black hair and designer stubble, George had that unique quality – men wanted to be his best friend and women wanted to marry him. The chat-show host Michael Parkinson, who knew many a handsome movie star and sportsman, says that George was the biggest babe-magnet of them all. The Irishman used to wear a gold chain around his neck with the simple wording ‘Yes’, which presumably helped him to cut out unnecessary conversation on his nights out pulling women.

George and Michael Parkinson. The Scotsman

His amazing displays during the early years of his career peaked in 1968, when he played a starring role in United’s 4–1 win over Benfica in the European Cup final. But his behaviour after the game on the night that should have been his greatest triumph revealed the extent of his growing drink problem. Many years later, he confessed that he could not remember anything of the post-match celebrations in London’s West End. His drinking, which he attributed to his own shyness and inability to come to terms with his pop star status, grew progressively worse, and by his own account he was an alcoholic by 1972. (Unfortunately, this admission only came later in life; when he arrived in Edinburgh George was still in denial and refusing to admit that he had a drink problem.) George’s speciality was three or four-day binges to ‘forget about everything’ – these drinking bouts usually arrived without warning and invariably at times when things were looking positive for George. He once told the ITV football programme On the Ball: ‘I want to be the best at everything, even boozing. That’s my nature.’ If the party lasted for four hours then George would stay for five. And when he was drinking, nothing else mattered, not even money. He once lost out on a TV commercial that would have paid him £20,000, just because he was due to have a drinking session with his mates on the same day as the advert was to be shot.

The binge drinking continued off and on throughout the rest of his life. Through the 1970s, George’s alcoholism became an ugly spectator sport that just about everyone in Britain had a view on. His career had turned into something of a freak show after he walked out on Manchester United for the last time in December 1973. A couple of years later, he was hawking his wares at Dunstable Town in the Southern League. Then he moved on to Stockport County, Los Angeles Aztecs and Cork Celtic before finally finding a semblance of happiness at Fulham in 1976, playing alongside another pair of faded superstars in Bobby Moore and Rodney Marsh. But, predictably, when things got difficult at Craven Cottage, George did a runner back to Los Angeles. While Fulham languished in sixteenth place in Division Two, George was content to go on three to four-day long binges in shabby Los Angeles bars. By 1979, George was at his lowest ebb and playing fitfully for the Fort Lauderdale Strikers in the NASL. His longsuffering wife, Angie, had walked out on him (only to return shortly afterwards) with the famous line: ‘You’re wasting your life George, you’re not going to waste mine as well.’ Best was starting to resemble a tramp, occasionally sleeping on beaches between drinking bouts. He was also wracked with guilt over the death of his mother Ann in October 1978. Like her famous son, Mrs Best had a serious drink problem that contributed to her dying from heart disease. George blamed himself for not being there when his mother needed him most and he became increasingly depressed, finding it difficult to share his true feelings with others.

George with Manchester United manager Tommy Docherty. Getty Images

In previous years, he could always escape from his worries on the football pitch. Now, even that option was starting to fade away. Manchester United had cruelly said no to a testimonial for the club’s most famous son and Best understandably felt annoyed by the refusal. Around this time, he also unwittingly broke the terms of his registration by playing some invitation matches for an American team in Europe and was banned by the football authority FIFA from playing anywhere in the world. Although the ban was eventually lifted, it helped contribute to the image of George as yesterday’s man. Running out of options stateside, George returned to England eager to settle down, and initially moved to Southend to live with Angie and her parents. Still registered with Fulham, who allowed him to train with the first-team squad at the Bank of England sports ground in Roehampton, Best had appeared on ITV’s World of Sport to say he would play for free with any English First Division team to prove his worth. There were no takers. George talked about interest from eight English clubs, including two First Division teams, but in reality there was no sign of a contract being offered. So when Hibs chairman Tom Hart came calling, Best must have thought, ‘what have I got to lose?’ Angie Best recalls: ‘When Hibs got in contact, it was a desperation point for George. He was at a very low ebb. George was always keen on any idea or offer that would help him to get better, because he never knew how to help himself, he kept failing and failing, and the offer from Hibs came at an ideal moment.’ Vowing, not for the first – or last – time, to give up the booze, Best accepted the Hibs offer. So the man described as the most exciting footballer and most frustrating employee of his day ended up at Easter Road. In one sense, it wasn’t wholly a leap into the unknown: the Best family had Scottish roots. George’s paternal grandfather, James ‘Scottie’ Best, was raised in Glasgow and worked for some time at the Clyde shipyards before returning to Belfast to work at Harland and Wolff. During his son’s year in Edinburgh, George’s father made frequent visits to Scotland and apparently felt right at home and had many friends here, especially in Glasgow.*

When he signed for Hibs, Best was already well into the downward spiral which would eventually leave him bankrupt and beaten by alcoholism. Vodka was his poison of choice, and he could pack it away with frightening ease: he once drank a pint of the stuff in one go just to win a bet. Jim Blair, the late, great Daily Record columnist, once said that George was the type of guy that even the Samaritans would hang up the phone on. A trifle harsh, but George did have an uncanny knack of messing up just when it seemed easier to do the right thing. Angie had done her best to sort out his financial affairs and help his fight against alcoholism, but it wasn’t easy: they had already split up four times since their marriage in 1978, only to get together again and soldier on. It also couldn’t help that George’s life away from football revolved around licensed premises. Even near the end of his spell in Edinburgh, he still had a one-third share in a bar on Hermosa Beach in LA and substantial interests in two nightclubs – Slack Alice’s and Oscar’s in Manchester.

But as is often the way, the public seemed to love him all the more because of his flaws; there was something reassuring that someone with so much talent could also have the same weaknesses as the ordinary bloke on the street. Although his problems often got the better of him, George was at heart a good person. As his sister Barbara described him: self-effacing, down to earth, mild-mannered and not at all pretentious. All these attributes were to the fore during his time in Edinburgh. As teammate Jackie McNamara says: ‘He was a marvellous guy and everyone really liked him.’ The public could also see that, unlike many of his fellow footballers, George was an intelligent man. Anyone who heard him speak on the chat show Parkinson in the 1970s will recall him as witty and eloquent. He was a keen reader with an offbeat taste in fiction – one person I spoke to remembers George being aware of the Jerzy Kosinski novel Being There long before it was adapted into a film starring Peter Sellers. George also had a keen interest in biographies; in one interview, he said: ‘I am fascinated by Hitler and the mass murderer Charles Manson – they were evil but radiated fantastic power.’ George himself harboured little-known but genuine writing ambitions – he told one reporter that his dream was to own a 20-bedroom hotel where he could write novels.

A one-year contract with Hibs allowed George to train in London during the week and then fly up to Edinburgh on Thursday, train with the rest of the squad on Friday and fly back to London on the Saturday night. But as Ally MacLeod, Hibs’ top striker back then, told me, this arrangement was hardly conducive to getting the best out of the mercurial Northern Irishman. Ally and several of the other older heads at Easter Road had reservations about the signing, although they were soon won over by the star’s homespun personality and his ability on the pitch.

Following a pattern set throughout his career, George initially knuckled down, training hard and staying sober. When he was in the right mindset, he actually loved working on the pitch and the feeling of getting fit again. And when he did turn up for the Hibs training sessions, he worked overtime with younger players on improving their skills. Hibs’ manager Eddie Turnbull gave Best the No. 11 shirt and a free role on the pitch, but with his main position being left of midfield behind the strikers. His arrival immediately lifted a squad beset by self-doubt. But he was more than a stone overweight and both his ankles were bloated after years of being hacked by journeymen full-backs. One fan, the MSP Iain Gray, told me how near the end of games, George seemed to gravitate towards the tunnel so he didn’t have too far to walk at full-time.

Best’s year at Hibs saw his physical condition deteriorate further. While in London or Manchester, he was drinking and not bothering to train so the couple of days – at most – he spent training in Edinburgh were never going to be sufficient to get him fit for the hard grind of a winter playing in the Scottish Premier League. And the more he drank, the more depressed and lonely he became. Sadly, his time at Hibs is often remembered more for him going AWOL – or as he called it ‘going on the missing list’ – generating frustration rather than excitement. On one occasion, he set off for the airport, then decided he couldn’t be bothered and stayed in London boozing. Another time, he actually managed to arrive at Edinburgh airport, only to catch the next flight back down south.

If he was a Rolls Royce in his heyday, George was more like a Vauxhall Cavalier by the time he arrived at Easter Road. Those ex-Hibs players who were interviewed for this book almost always mentioned how, although he still had the ability to do things other footballers could only dream of, he had ‘lost the pace’. Also, his shoulder blade was just recovering from being fractured during his time at Fulham, when he crashed a borrowed Alfa Romeo car at 4 a.m. after a night boozing. He wrapped the expensive vehicle around a lamppost outside Harrods and also had to have 57 stitches in his face as a result of the smash. Eddie Turnbull rated George at his peak as one of the all-time greats, along with Cruyff, Maradona and Pele, but Turnbull was secretly dead against the Irishman’s move to Easter Road. In his biography, Turnbull recalls the moment when he looked George straight in the face and saw damaged goods: ‘His blue eyes had the look of a hard drinker about them, the yellowing skin around them a sure sign. I had seen plenty of faces like it in my career, and there was no mistaking the signs of someone who was on the skids.’

If George Best had any genuine hopes of kicking the booze into touch, then Edinburgh was not the ideal place for him to move to in 1979. Then, as now, Scotland’s capital was one of the champion drinking cities in Europe. George had a wide range of licensed premises to choose from. Annabel’s on Semple Street was the city’s most luxurious nightclub/disco – the only establishment in the UK to boast 24-carat gold-plated tables and chairs, it was open every night of the week until 3 a.m. At the other end of the luxury scale, the Clan Bar, Dizzy Lizzie’s, and the Royal Nip were some of Leith’s more notorious hostelries. The Clan on Albert Street occasionally pulled in the punters with male go-go dancers. The sight of those dancers never really leaves the memory – if you didn’t need a drink before seeing them, you certainly needed one afterwards.

George, the centre of attention. Scran

To begin with, George stayed at the North British Hotel (also known as the NB and now the Balmoral) at the east end of Princes Street, an imposing and luxurious Edwardian building which attracted the very rich and famous. If Tom Hart was trying to keep Best on the straight and narrow, he couldn’t have picked a worse place. The NB’s own bars were impressive enough, but the hotel was also within walking distance of many of Edinburgh’s finest watering holes, including the Café Royal and the pubs of Rose Street. The Daily Express journalist Andy McInnes told Stephen McGowan how when he once interviewed the star in the NB hotel, the waiter brought George his ‘usual’ – what appeared to be a large glass of Coke. ‘Only when I went to pay the bill and studied the receipt,’ McInnes recalls, ‘did I notice that he had four vodkas poured into the Coke. No wonder it looked so large. And this was his usual.’

The Hibs players’ own pubs of choice were Sinclair’s on Montrose Terrace (now the Terrace Inn), Leerie’s Lamplighter on Dublin Street on Saturday nights and Jinglin’ Geordie’s* during the week. The latter pub, on the city’s Fleshmarket Close, was also a favourite hang-out of hacks from The Scotsman and Evening News who only had to sway a few steps from their back door to the pub. The Jinglin’s landlord back then, David Scrimgeour, gave me a quick history of the tiny wee bar that was to become synonymous with George Best.

‘Jinglin’ Geordie’s used to be a pub called the Suburban Bar and it was a right honky-tonk slum of a place,’ he said. ‘A great pal of mine at the time was the chairman of Bass the brewers and when I was chatting to him one day about journalism and our favourite hostelries, he asked me if I ever thought of running a pub myself. I initially said no, but eventually I ended up getting the Suburban Bar and the brewers very kindly demolished the interior and did it up to a very high standard. The place used to be mobbed all the time – I had four staff on the go continuously. There were 1,500 employees at The Scotsman building who were all well paid, and a fair proportion of them liked a drink, plus we catered for all the traders from the Fruitmarket.’

The mix of journalists and footballers meant that Edinburgh was soon ablaze with rumours of what the Irish playboy was getting up to in his spare time. The intentions of some of the reporters weren’t always honourable. Friends remember a ‘conveyor belt’ of women waiting their turn to meet George. Different people I spoke to remember the effect he had on the female population of Edinburgh, with old grannies going weak at the knees in his presence. Others just gravitated towards him, stretched out a hand to touch him and then retreated back to their seats without saying a word.

* Angie Best’s mother is also Scottish.

* The Jinglin’ Geordie pub is named after George Heriot, jeweller and goldsmith to King James VI. Heriot amassed a considerable fortune during his lifetime and earned his nickname as he ran beside the king’s coach with coins jingling in his pockets. A bequest in his will founded George Heriot’s private school in the capital.

CHAPTER TWO

JOURNEYMEN

Being a Hibs fan has never been a job for the glory hunter. Founded in 1875 by the Irish community in Scotland’s capital, the club had lasted for 104 years before George Best arrived on the scene and in all those years, Hibs had won just seven major competitions: four League Championships, two Scottish Cups and one Scottish League Cup. It’s the type of record that leads fans to adopt a stoical attitude. A good sense of humour helps, too. Edinburgh-born war veteran John ‘Jock’ Wilson spent almost a century watching Hibs before his death in 2008, aged 105, and he knew better than most that following the Leith outfit requires a strong sense of self-deprecatory humour. Commenting on the Military Medal earned on active service, Jock would quip: ‘Well, I didn’t get it for following Hibs for 90 years – that would deserve the Victoria Cross.’ The comedian Bill Barclay, who was born and raised in Leith and has been a Hibee all his life, once joked: ‘I remember the last time we were in Europe, the fans let us down coming back on the ferry. They pulled down all the sails and threw the canons over the side.’

But the gallows humour and bare statistics don’t tell the whole story. For all their occasional spells of mediocrity, Hibs have frequently had a reputation for innovation and for playing free-flowing expressive football. In the decade following the end of the Second World War, they won three league titles. Back then, their forward line – nicknamed The Famous Five – were a wonder to behold. Bobby Johnstone, Willie Ormond, Lawrie Reilly, Eddie Turnbull and Gordon Smith were feared and respected throughout Europe. Fast-forward 20 years and Eddie Turnbull as manager at Easter Road put together another mighty side. Known as Turnbull’s Tornadoes, Hibs in the 1970s were a team laced with entertainers, and names like John Brownlie, Pat Stanton, Alex Cropley, Alex Edwards, Alan Gordon and Jimmy O’Rourke are still revered down Leith way. Stanton in particular was a class act. Simon Pia, who has written a couple of great books about Hibs, told me: ‘For most fans of my generation, there can only be one man – Patrick Gordon Stanton. A great tackler and passer of the ball, Pat was also a goalscorer and particularly good in the air. He played with elegance, with his head up and always seemed to have so much time, reading the game so well.’

Stanton’s Hibs triumphed twice in the now defunct Drybrough Cup and also won the League Cup once with a stirring 2–1 win over Celtic in season 1972–73. That victory was the Tornadoes’ finest performance, with Pat Stanton providing a peerless display, outshining a Celtic side that contained legendary names like Danny McGrain, Kenny Dalglish and Jimmy Johnstone. The Tornadoes also reached the Scottish Cup final in 1972 and had some memorable nights in Europe throughout the 1970s. A good deal of the credit for the team’s success must go to their manager, Eddie Turnbull. As Jackie McNamara, who came to Easter Road in an unpopular swap deal which saw Pat Stanton go to Celtic, recalls: ‘As a manager, Eddie Turnbull was second to none. He’s the best I ever worked under. I don’t like to draw comparisons with [Jock] Stein because I worked with Big Jock near the end of his career and in a way he had already done it all, maybe the hunger wasn’t really there for him anymore. Turnbull would put you into a situation in training and 99 times out of 100 when you played on a Saturday that training situation would help you deal with the real thing during the match. He could be a hard man, but I was a bit of a favourite of his because of all the stick he got when he signed me. But Pat Stanton ended up retiring the season that he signed for Celtic and Turnbull got another ten years out of me.’

By the end of the 1970s, the great Hibs team had mostly gone their separate ways, lured from Edinburgh by the prospect of higher wages and more regular success on the field. John Brownlie and John Blackley had headed to Newcastle, Blackley for £100,000 and Brownlie leaving as part of the deal which took Ralph Callachan to Easter Road. O’Rourke, Gordon and Edwards had also moved on and even promising youngsters like Bobby Smith – who was sold to Leicester City – were also being shipped out of Leith. What was left was a shadow of the early 1970s outfit. Part-time chiropodist Arthur Duncan was one of the few remaining from the great side, but even he had reverted from being a buccaneering winger to a fullback with licence to overlap.

Arthur Duncan. Copyright unknown

Ian Wood, who has worked at The Scotsman