Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: McNidder and Grace

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

William Armstrong was a brilliant and charismatic figure of the 19th Century – a self-made man whose achievements are now being more widely recognised. Inventor, scientist, engineer, and an early advocator of renewable energy, he built a pioneering house in Northumberland in the North East of England called Cragside, the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectricity. Armstrong's industrial powerhouse Elswick Works on the Tyne employed over 25,000 people in its heyday manufacturing hydraulic cranes, warships and armaments. He was a visionary who was loved, and hated, and feared in equal measure. While he brought great fame and fortune to his native Newcastle upon Tyne, and to his country as a whole, he was condemned in some quarters as 'a merchant of death' for his manufacturing of weapons of war. 'This intimate, authoritative portrait reveals as never before the extraordinary achievements of a multi-faceted Victorian giant.' David Kynaston 'An excellent book – hugely enjoyable.' Alexander Armstrong

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 689

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WILLIAM ARMSTRONG

MAGICIAN OF THE NORTH

Henrietta Heald

CONTENTS

Title Page

List of illustrations

Foreword

Sources and acknowledgements

1 Xanadu

2 The Kingfisher

3 Brilliant Sparks

4 Rivers of Pleasure

5 Maister o’ th’ Drallickers

6 What News from Sebastopol?

7 National Hero

8 A Bigger Bang

9 Restless Spirits

10 ‘However High We Climb’

11 Paradise on Earth

12 High Tide on the Tyne

13 Enlightenment

14 Stormy Undercurrents

15 Egyptian Interlude

16 Natural Forces

17 The Rising Sun

18 Baron Armstrong of Cragside

19 King of the Castle

20 The Philosopher Crab

21 Rise and Fall of an Empire

Family Tree

Index

Plates

Copyright

List of Illustrations

Illustrations are reproduced by permission of named organisations and individuals.

Pandon Dene (Newcastle Libraries); Jesmond Dene, Armstrong’s house (Laing Art Gallery)

Elswick in the 1840s (Newcastle Libraries); Elswick in 1887 (Illustrated London News)

Armstrong’s first gun (Newcastle Libraries); gun trials at Shoeburyness (Illustrated London News)

The gunboat Staunch (Illustrated London News); HMS Victoria passes through the Swing Bridge (Newcastle Libraries)

The Japanese ships Yoshino and Yashima (both Newcastle Libraries)

Cragside lit by electricity (Graphic)

South-east Asia in the late 19th century (map by Bryan Kirkpatrick)

Admiral Togo with the Nobles;Japanese sailors in Newcastle (both Newcastle Libraries)

Cragside library and drawing room (both National Trust Cragside)

Plate section

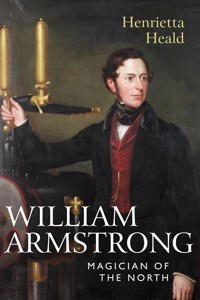

William Armstrong at 21 (National Trust Cragside, artist James Ramsay)

Anne Armstrong senior (National Trust Cragside)

William Armstrong senior (National Trust Cragside)

Margaret Armstrong, née Ramshaw (Bamburgh Castle, artist J. C. Horsley)

Anne Armstrong junior (National Trust Picture Library, photo Derrick E. Witty)

Jesmond Dene map; Jesmond Dene banqueting hall (both Newcastle Libraries)

Armorer Donkin (National Trust Picture Library, photo Derrick E. Witty)

Thomas Sopwith with William Armstrong (Robert Sopwith)

James Meadows Rendel; George Rendel (both Vickers Archive)

General Grant visits Elswick (Newcastle Libraries)

Gun testing on Allenheads moor (Robert Sopwith)

Li Hung Chang at Cragside; the Chinese ship Chih Yuan (both Newcastle Libraries)

Richard Norman Shaw’s vision of Cragside (Laing Art Gallery)

Cragside today (author)

Armstrong in the dining room at Cragside (National Trust Picture Library, photo Derrick E. Witty, artist H. H. Emmerson)

Armstrong in baronial robes (Bamburgh Castle, artist H. Schmirchen)

The royal family at Cragside (National Trust Picture Library, top photo John Hammond, bottom photo Derrick E. Witty, artist H. H. Emmerson)

Armstrong at Cragside; the launch of Pandora (both Newcastle Libraries)

An architect’s sketch of Bamburgh Castle; castle scaffolding (both David Ash)

Bamburgh Castle today (author)

Launch card for Albany (Newcastle Libraries)

Launch cards for Tokiwa and Asama (Newcastle Libraries)

Image from Electric Movement in Air and Water (Newcastle Literary and Philosophical Society)

Raising the bascules of Tower Bridge (Shutterstock.com)

Armstrong Mitchell crane in the Venice Arsenale (Venice in Peril)

Foreword

I discovered William Armstrong in Jesmond Dene. I had visited Cragside a couple of times and, like millions before me (Cragside welcomed its four millionth visitor in the summer of 2009), had marvelled at Armstrong’s amazing inventions, his taming of the landscape, and the quirky originality of the house he had built amid the bleak Northumberland moors. Later I learnt that he had made his money from industry on the Tyne, from the manufacture of cranes, ships and – sharp intake of breath – guns. But it was not until I had taken several solitary walks at dawn and dusk across the soaring Armstrong Bridge, a romance in wrought-iron and sandstone, and wandered along the banks of the Ouseburn that I really began to get the measure of the man.

Jesmond Dene is a unique urban gem. Little more than a mile from the centre of Newcastle, the vibrant heart of north-east England, the dene is a deep cleft in the landscape whose steep and wooded banks frame an enchanting burn that is sometimes gentle, sometimes tempestuous as it rushes past rocks and flows over rapids. Running north–south into the Tyne, the Ouseburn is the lure that induced Armstrong to make a home there in the 1830s with his new wife, Meggie Ramshaw.

As the years went by, the Armstrongs acquired, through purchase and inheritance, more and more land along the dene. Not content with the natural beauty of the place, they set out to improve what they found there, landscaping both the river and its banks, adding waterfalls, stepping stones, paths and bridges, and cultivating many exotic as well as native trees and plants. The aim – achieved more obviously and dramatically at Cragside – was to recreate the experience of being in the mountains, and to do it as unobtrusively as possible. ‘I am a greater lover of nature than most people give me credit for,’ wrote William Armstrong in 1855, ‘and I like her best when untouched by the hand of man.’

The shaping of Jesmond Dene was much more than an act of self-indulgence, however. Like many of Armstrong’s achievements, it had far-reaching significance. When he handed over almost 100 acres of his land in the dene to the city of Newcastle as a public park, he made it clear that his main motivation was to improve other people’s quality of life. He had earlier built a banqueting hall in the dene – intended not for sumptuous feasting but as a place where he could hold tea parties for his employees at Elswick Works. The mighty industrialist, whose workforce would at times number more than 25,000, understood the importance to working people of leisure, reward and open-air recreation, and it was in this spirit that he made a gift of the dene to his fellow citizens.

By mid-2005 I was scouring shops and libraries for books about this enigmatic figure, but found nothing that could genuinely satisfy my hunger. At the same time, the more I talked to people, the more I realised that the name Armstrong had tremendous resonance in Newcastle. There was the Armstrong Building, the bedrock of Newcastle University, for example, and the elegant low Swing Bridge across the Tyne, which would swing open (as it still does after 140 years) to allow ships to pass either side of its central axis. Those in the know pointed out that the hydraulic mechanisms Armstrong had pioneered in the construction of the Swing Bridge were later adapted to open and close the giant bascules of London’s Tower Bridge. There was even a statue of the great man and his dog outside the Hancock Museum, one of Newcastle’s favourite institutions, now reincarnated as the Great North Museum. He had contributed £100,000 to the Royal Victoria Infirmary, opened in 1906. And didn’t he have something to do with the Lit & Phil – that venerable institution near Central Station, founded at the time of the French Revolution, which played a leading role in Newcastle’s intellectual flowering in the mid-19th century, and survives to this day?

Those with more recent memories mentioned Vickers-Armstrongs, the mighty defence contractor that continued as a major employer on Tyneside until well into the 1980s. Before that it had been Armstrong Whitworth with its formidable Walker Naval Yard and, even further back, Armstrong Mitchell, producer of gunboats and fast cruisers for all the world’s leading navies. And how did the popular car-maker Armstrong Siddeley and the aviation firm Hawker Siddeley fit into the picture? Much later, I learnt that Bamburgh Castle on the Northumberland coast had been bought and restored by Lord Armstrong (as he was by then) in the last few years of his life – and that the castle was still owned and tended by members of the Armstrong family.

By the time I realised that 2010 was the bicentenary of William Armstrong’s birth – he was born the year after Charles Darwin – I knew that I should be writing his biography. His 3,000-word obituary in The Times made it clear that he had been a national hero who was seen by many as Britain’s saviour at a time of grave threat from hostile forces, and his fame stretched around the globe, from Chile to Italy to Japan. How could it happen that this remarkable figure had been almost forgotten in his native land – especially when dwindling energy supplies, industrial decline, and the threat of global warming meant that we were more than ever in need of his scientific genius, to say nothing of his inspirational business skills?

By reviving Armstrong’s thoughts and ideas as expressed in his own writings, Magician of the North attempts to reach a deeper understanding of his achievements, and to penetrate the desires and motivations that spurred one great Englishman to pursue single-mindedly the path to true knowledge.

Henrietta Heald

Sources and Acknowledgements

Ken Wilson, a National Trust volunteer at Cragside for almost two decades, has an interest in William Armstrong that dates from the Second World War, when, as a young boy, he was evacuated from Tynemouth to Rothbury. Ken has amassed an extensive archive of written material, images, film clips, and sound recordings relating to Armstrong, Cragside, and the Armstrong family, to which he has allowed the author unlimited access. Without Ken’s diligence and generosity this book could not have been written. Zena Chevassut, a friend and colleague of Ken, carried out useful research into Armstrong’s father’s family and uncovered some intriguing documents, including the younger Anne Armstrong’s lakeland diary.

One of Ken Wilson’s most important discoveries was an unpublished history of the Elswick Works, written in the late 1940s to mark the centenary of the founding of the works. A. R. Fairbairn, the author of this fascinating and detailed document, has been described as works architect at Elswick, but he died before the book could be published, and in the event a much shorter version of the firm’s history was published by what was then Vickers-Armstrongs. Little more is known about Fairbairn except that he was an enthusiast for Esperanto. An anonymous preface to the Fairbairn typescript, a copy of which was deposited in the Vickers’ archives at Cambridge University Library, describes his work as ‘most accurate’ and mentions that his research was ‘used extensively’ by J. D. Scott, the author of Vickers: A History, published in 1962. What is known about Elswick’s history from other sources is corroborated by Fairbairn’s account, and the author is indebted to him for many details not recorded elsewhere.

The largely unpublished journals of Thomas Sopwith, written over a period of 57 years, from 1822 until his death in 1879, are a treasure trove of information, not only about Sopwith’s great friend William Armstrong but also about the Victorian age and, in particular, its scientific luminaries. The diarist’s descendant Robert Sopwith, the guardian of the original 168 leatherbound volumes, has kindly granted the author permission to quote freely from them and to reproduce the photograph of Sopwith and Armstrong taken in 1856. A microfilm version of the diaries forms part of the Special Collections at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University.

Peter McKenzie, a former employee of Vickers who wrote a short biography of Armstrong in 1983, also provided invaluable information, including helping to explain what happened to the various Armstrong companies after the merger with Vickers in 1927. Peter put the author in touch with Rosemary Rendel, the granddaughter of Armstrong’s protégé George Rendel, who had herself carried out extensive research into the Rendel family and their engineering achievements, with a view to publishing her own book on the subject. Despite her advanced age, Rosemary was a fund of fascinating stories about the Rendels and gave permission for quotations from family correspondence. Thanks are also due to Jonathan and Jane Rendel and Christopher Rendel. Even before the author read Peter McKenzie’s W. G. Armstrong, the life and times of Sir William George Armstrong, Baron Armstrong of Cragside, she had been inspired by Ken Smith’s illuminating but all too brief account of Armstrong’s life, Emperor of Industry.

Since virtually everything Armstrong said and wrote is either unpublished or out of print, the author has relied heavily on the assistance of librarians and archivists, in particular Liz Rees and her excellent team at Tyne & Wear Archives, which holds a vast collection of items relating to the Armstrong, Watson-Armstrong, and Rendel families and businesses, including hundreds of letters written by William Armstrong on both personal and professional matters; for the sake of space, these are not listed individually in the chapter notes. The author would also like to thank the staff at the British Library (especially those in the Rare Books reading room); Robinson Library, Newcastle; Durham University Library; Cambridge University Library; the Bodleian Library, Oxford; and the libraries of the London School of Economics (LSE) and University College London (UCL).

Particular thanks are due to Martin Dusinberre of Newcastle University for his insights into Armstrong’s relations with Japan; Brendan Martin for his comments on industrial relations in late Victorian Britain; and John Clayson of Newcastle’s Discovery Museum for his lucid explanation of scientific and engineering matters. John Clayson co-curated with Laura Brown a major exhibition at the Discovery Museum of Armstrong’s life and works. Other individuals who helped with research and provided advice on improvements and amendments include Stephen White of Carlisle Library and Richard Sharp of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne (the Lit & Phil) (William Armstrong senior); Celia Lemmon (James Losh and the Losh family); Jo Hutchings and Frances Bellis of Lincoln’s Inn Library (William Henry Watson); Michael Hush of the Open University (engineering); Adam Hart-Davis (hydraulics); Norman McCord (industrial relations); James Tree (Hollist family); and last, but by no means least, the redoubtable Ian Fells, emeritus professor of energy conversion at Newcastle University.

The custodians and staff at Cragside and Bamburgh have given generously of their time and wisdom. Among those currently or historically associated with Cragside, the author would like to thank, in particular, Alison Pringle, Andrew Sawyer, Robin Wright, John O’Brien, Pam Dryden, Kate Hunter, Dennis Wright, Pamela Wallhead, Justine James, Carole Evans, Caroline Rendell, Hugh Dixon, Helen Clarke, and Sadie Parker. At Bamburgh, Lisa Waters and Chris Calvert have been unstinting in their help and support, and through them the author had the pleasure of meeting Francis Watson-Armstrong and Claire Thorburn; among others with a Bamburgh connection, the author would like to thank Carol Griffiths and Charles and Barbara Baker-Cresswell. Thanks are due also to Seamus Tollitt, Ouseburn Parks Manager, Robert Wooster and Sarah Capes, who enabled the author to consult the Jesmond Dene archives, and to Anna Newson, Tom Hope, John Penn, Carlton Reid, and other Friends of Jesmond Dene.

Special mention should be made of the architects and students of architecture who have directly and indirectly contributed to this book. Heading the list is Andrew Ayers, who, in the mid-1990s, was the first to whisper the name ‘Cragside’ to the author, then an ignorant Londoner. Next is Terry Farrell, whose autobiography opened the author’s eyes to the wonders of Newcastle and introduced her to John Dobson, the man who, with Richard Grainger, rebuilt the town in the 1830s. Farrell quoted the traveller William Howitt, who, writing in 1842, captured the sense of surprise still felt today by newcomers to Newcastle: ‘You walk into what has long been termed the coal hole of the north and find yourself at once in a city of palaces, a fairyland of newness, brightness and modern elegance.’ The work of Richard Norman Shaw, the architect of Cragside, remains a continuing source of fascination, especially as elucidated by his biographer Andrew Saint. The list continues with the eminent architect David Ash, who, like Farrell, spent his undergraduate years at Newcastle University, where he wrote a thesis on the history and restoration of Bamburgh Castle, which remains unrivalled today in the depth and thoroughness of its research. Likewise, Jeremy Blake of Purcell Miller Tritton, a leading firm of ‘green’ architects, wrote a dissertation on Cragside during his student years. Both Ash and Blake have been generous in giving the author permission to quote from their works. Neil Cossons, Geoff Wallis and E. F. Clarke are among the engineers who have provided particular inspiration.

Other scholarly works that have proved invaluable to the author in writing this book include Marshall J. Bastable’s Arms and the State: Sir William Armstrong and the Remaking of British Naval Power 1854–1914; Kenneth Warren’s Armstrongs of Elswick: Growth in Engineering and Armaments to the Merger with Vickers; and a PhD thesis by Alice Short, The Contribution of William Lord Armstrong to Science and Education (Durham University, 1989).

Plans to mark the bicentenary in 2010 of William Armstrong’s birth brought the author into contact with many people in Newcastle and elsewhere in Britain whom she would like to thank for their help and encouragement. In no particular order, they include: Penny Smith, Don MacRaild, Chris Dorsett, and Gill Drinkald of Northumbria University; Iain Watson and others at Tyne & Wear Museums; Graeme Rigby of Amber Films; Alex Elliot (actor); Matt Ridley (writer); Valerie Laws (poet); Sue Aldworth (artist); Linda Conlon of the International Centre for Life; Caspar Hewett of the Great Debate; Kay Easson and Chris Sharp of the Lit & Phil; Paul Younger, Frances Spalding, and Umbereen Rafiq of Newcastle University; Frances Clarke, Anna Somers-Cox and Nicky Baly of Venice in Peril; Neil Tonge, Ben Smith, Ian Ayris, Richard Faraday, Craig Brown, and other members of the Armstrong 200 Group; Phil Supple of Light Refreshment; Zoe Bottrell of Culture Creative; Jim Lepingwell of Patchwork Planet Productions. Supporters at the BBC have included Julian Birkett (producer of Jeremy Paxman’s The Victorians) and Martin Smith, who invited the author to take part in the BBC Free Thinking festival of ideas at the Sage, Gateshead, in October 2009.

Broo Doherty of Wade & Doherty has proved to be the best literary agent any new writer could hope for. The author would also like to give particular thanks to Andrew Peden Smith of Northumbria University Press for believing in the project from the start and throwing his intellectual weight behind it; Laura Booth and Laura Hicks for astute copy-editing and indexing; Linda MacFadyen (friend and publicist) for her energy, loyalty, and original thinking; Mark Stafford for general assistance; and Andy Tough, the guiding hand behind the William Armstrong website (www.williamarmstrong.info).

Friends and relations who have contributed to Magician of the North are too numerous to thank individually, but I should like to single out a few for special mention: Max Eilenberg and Caz Royds for urging me to become a writer; Ariane Bankes for her support and encouragement at every turn; my loved and loving husband, Adam Curtis; and my wonderful children, Sophie and Jamie Curtis.

1

Xanadu

It was 19 August 1884 – a hot and dazzling Tuesday in Newcastle upon Tyne. At 5.25pm, two minutes early after its 5¾-hour run from London, the royal train steamed triumphantly across the High Level Bridge into John Dobson’s magnificent Central Station, where a dense crowd surged forward, eager to catch a glimpse of the occupants. The portly middle-aged Prince of Wales was of secondary interest, but his popular Danish wife, Alexandra, and their five children, aged from 14 to 20, were greeted with exultant cheers and wild flag-waving. Never before had the young princesses, Louise, Victoria, and Maud, and their elder brothers, Albert Victor and George, accompanied their parents on such an expedition.

Although it was the first royal visit to Tyneside since 1854, there was no time at that moment for anyone to disembark. The train had halted for barely five minutes, taking on board a group of local dignitaries, before it swept north out of the curving station and disappeared into the distance in the same stately fashion as it had arrived.

For that evening, at least, a more rural destination beckoned. The royal party’s chosen resting-place during its three-night stay in the English borderland was the village of Rothbury on the River Coquet. There the princes and princesses would enjoy the hospitality of Sir William and Lady Armstrong at Cragside – an astonishing modern house in the Old English style, carved out of bleak Northumberland moorland. As the Prince of Wales stepped out onto Rothbury’s crimson-carpeted platform, one hour and a quarter after leaving Newcastle, a tall, elegant, top-hatted figure detached itself from the welcoming committee and stepped forward to shake hands with the heir to the throne.

William Armstrong had first met the Prince of Wales at the opening of Great Grimsby Docks by the Queen and Prince Consort 30 years earlier, when Albert Edward was a 13-year-old boy. On that occasion, the prince had been given a thrill by one of Armstrong’s early inventions, when he, his father, brothers, and sisters were hoisted up the 300-foot-high water tower by a hydraulic lifting mechanism. Armstrong described in a letter to his wife how the Queen stood laughing at them below. ‘Certainly the hydraulics were the great attraction,’ he wrote, ‘and I’ll be bound for it will be talked about by the children as long as they live … The Queen very nearly agreed to go up in the hoist but time was too pressing.’

At Cragside, furious preparations for the royal visitors had been under way for several weeks – ever since it had become clear that the Prince of Wales had spurned the Duke of Northumberland’s offer of accommodation at Alnwick Castle in favour of an opportunity to stay at the home of the world-famous engineer. The size of the royal retinue had made it necessary for the Armstrongs to reserve the entire County Hotel at Rothbury, in addition to Cragside itself, for the use of the visitors. Twenty extra male waiters had been employed to serve the guests at meals – outnumbering the permanent staff in the house. Margaret, Lady Armstrong had engaged London caterers approved by the Prince of Wales and ensured he would be well supplied with his favourite champagne. The menu for the first dinner included oysters, clear turtle soup, pâté de foie gras, stuffed turbot, roast haunch of venison, grouse, and iced chocolate soufflé.

By good fortune, the architect Richard Norman Shaw had just completed his 15-year transformation of Cragside from an unremarkable sporting lodge into a residence fit for a 19th-century emperor. Shaw had not only wrought wonders on the outside of the building, perched on a rocky ledge above the Debdon Burn, but also commissioned interior work by the best craftsmen of the day. The Prince and Princess of Wales would occupy the Owl Suite, which had built-in plumbing, Venetian wallpaper by William Morris, and exquisitely carved American black walnut furniture, including owl finials on the bedposts. Elsewhere in the house were Turkish baths and every modern convenience for the royal visitors. In the evening, the guests would gather before dinner in the magnificent drawing room, hung with paintings by Constable, Turner, and Millais – and dominated at the far end by a spectacular inglenook chimneypiece made of Italian marbles in blue, salmon, orange, and pink, and weighing 10 tons.

Set into the south front of the house was the Gilnockie Tower, named after the stronghold of one of Armstrong’s more notorious ancestors. Rather than the handsome high gable that Shaw had designed, the tower was topped off by a glass-domed observatory, where its owner would retreat to gaze at the stars.

But what entranced visitors to Cragside above all – and had won the house its reputation as ‘the palace of a modern magician’ – were the domestic gadgets created by Armstrong himself. Many were hydraulically driven, but others relied on electricity. In an astonishing development – following Armstrong’s damming of the Debdon Burn and his installation of a water-powered Siemens dynamo – Cragside had four years earlier become the first house in the world to be lit by hydroelectricity.

The immediate impact of this advance in human civilisation was evoked a century later by the writer and broadcaster June Knox-Mawer: ‘The wonders of science that Cragside could show were beyond any oriental palace-builder, even Kubla Khan himself. There were Sir William’s hydraulic inventions, for instance, which automatically turned the spits in the kitchens, sent the trays up and down by lift, revolved the plants in the conservatories, and beat the gongs for family prayers and meals. Most marvellous of all were the incandescent lamps that blazed out from the windows at night with a brilliance quite different from candle or gas.’1

It was appropriate, therefore, that the arrival of the royal party at Cragside should be celebrated by a festival of light. Outside the house, Armstrong had fitted a network of lights that illuminated the whole valley. ‘Ten thousand small glass lamps were hung amongst the rocky hillsides or upon the lines of railing which guard the walks, and an almost equal number of Chinese lanterns were swung across leafy glades, and continued pendant from tree to tree in sinuous lines,’ according to a contemporary account.2 ‘Clouds of little lamps hung like fireflies in the hollow recesses of the distant hills, and symmetrical designs in coloured lamps were placed along the steep flights of rustic steps which lead from the depths of the valley to the upper grounds on either side.’ The sight of the house itself was no less dramatic: ‘From every window the bright rays of the electric lamps shone with purest radiance, and the main front was made brilliant by a general illumination.’

At 10pm a magnificent display of fireworks took place on Rothbury Hill under the direction of James Pain of London and New York: ‘The woods and hills and dales were illuminated with every ray of the rainbow, rockets, monster balloons, shells, asteroids, and rayon d’or, batteries of Roman candles, electric shells, flights of tourbillons and “Mammoth Spreaders”, said to be the largest shells in the world, climaxed by a superb “aerial bouquet”.’3

Fears about setting fire to the heather having been overcome, a cone-shaped bonfire 20 feet high and consisting of huge logs of fir and pine and a large quantity of tar barrels was built on the highest summit of the nearby Simonside hills, with a similar one erected a few miles away at Elsdon. When the fires were set ablaze, they were visible not only from central Newcastle but also from Yorkshire, Cumberland, and the Scottish border, as well as from the most distant parts of Durham and Northumberland.4

Contrary to what the splendour of the event might suggest, the royal family’s host that summer’s night was no prominent local aristocrat. Although William Armstrong’s father had worked his way up from counting-house clerk on the Newcastle quayside to prosperous corn merchant and town councillor, his father’s father had made a meagre living in Cumberland as a shoemaker. Indeed, the Armstrongs were descended from a band of border reivers, or clannish outlaws, reputedly based in the ancient settlement of Bewcastle, north-east of Carlisle. In just two generations, the head of the Armstrong family had transmogrified from an unassuming artisan into a fabulously rich and sophisticated international businessman at home in the company of princes.

The festivities at Cragside – ‘one of the greatest galas ever seen in rural England’, according to Newcastle Weekly Courant – were a mere prelude to the substance of the official visit, which would not get under way until the following day. An original plan to invite the Prince of Wales to open a new dock at Coble Dene near the mouth of the Tyne at North Shields had expanded to include an extravaganza that would see the royal party progressing all over Newcastle, granted city status only two years earlier.

The outpouring of enthusiasm provoked by the occasion was reflected in the lavish decorations adorning the northern metropolis, with virtually every shop, public building, and monument festooned in flags, flowers, or evergreens, and triumphal arches spanning all the main roads on the route. Many otherwise unemployed local men had been paid to put up the decorations. The largest arch – 54 feet high and 42 feet wide – was built across Grey Street, with Grey’s monument resembling a gigantic maypole. The Times was particularly struck by the mass of illuminations and decorations and noted that the streets were so crowded that ‘locomotion was almost impossible’.

In a leader published the next day, The Times proclaimed that the arrival in Newcastle of the Prince and Princess of Wales was ‘something more than an ordinary royal visit to a flourishing town’. Commenting on the excitement of the citizens and the unusually brilliant scenes in the streets, the newspaper elaborated on the significance of the occasion: ‘As a guest of Sir William Armstrong, the Prince is regarded as identifying himself with Newcastle in an unmistakable way, for Sir William Armstrong’s is a name which embodies all the great industries and interests of the city, and his fellow-citizens are proud of him.’ This pride was well founded, for Armstrong’s importance as a major employer who had attracted a great deal of trade to Newcastle was matched only by his acts of generosity to local people, apparently stemming from ‘the pure goodness of his heart’.

The first task that the prince was due to perform – the opening of Armstrong Park – was an apparent reflection of this goodness of heart. Adding to an earlier gift of 20 acres, the industrialist was giving 62 acres of his land in Jesmond Dene, a renowned local beauty spot on the eastern edge of the city, to the people of Newcastle. The new public estate included a banqueting hall, built by Armstrong several years earlier as a place of entertainment for his employees at the Elswick Works – and since used to receive a multitude of eminent visitors.

Arriving at Central Station at noon, the royal family transferred to horse-drawn carriages and drove through the steamy city streets to the sound of cheering crowds, followed by more carriages carrying Sir William and Lady Armstrong and other members of the party. ‘Windows and roofs and every point from which a view could be obtained on the route was occupied,’ observed The Times. ‘On the roof of St Nicholas’s Cathedral choirs of the town were gathered, and as the royal guests came into sight they sang “God Save the Queen” and “God Bless the Prince of Wales”.’ At the request of the prince, the procession also passed through some of the more industrial and poverty-stricken parts of the city, including Byker.

Crossing Benton Bridge, an elegant iron structure built by Armstrong himself high above the Ouseburn, the procession wound its way down into the deep cleft of Jesmond Dene shortly before 1pm and, watched by some 6,000 spectators, made its way to the banqueting hall, where the Prince of Wales was presented with a golden key and asked to perform the opening ceremony. He remarked how glad he was that the park bore the name of Armstrong, after Newcastle’s great benefactor: ‘His name is known in the British dominions – I may safely say all over the world – as that of a great man and a great inventor. Not less known are his great liberality and his great philanthrophy.’ Then, a few yards from the banqueting hall, Princess Alexandra planted a young oak tree using a golden spade with a handle of black oak – a relic of Pons Aelius, the Roman bridge across the Tyne, which had survived for more than 1,100 years until its destruction by fire in 1248.

Ever since his parents had built a home there in the 1820s, William Armstrong had been under the spell of Jesmond Dene. Despite its proximity to Newcastle, the dene had a rugged, untamed appearance that reminded him of childhood visits to Coquetdale, the place that more than any other had captured his soul. In common with the contemporary Romantic poets, in particular Wordsworth and Coleridge, Armstrong was drawn to wild mountain landscapes, finding in them a thrill that amounted almost to a transcendental experience. ‘I am a greater lover of nature than most people give me credit for,’ he wrote later, ‘and I like her best when untouched by the hand of man. The mountain air and the vigorous exercise suit my constitution, and produce an exhilarating effect which sometimes almost amounts to intoxication, while the total absence of all restraint inspires a glowing sense of liberty which I never elsewhere experienced.’ At Jesmond Dene – and later, more dramatically, at Cragside – Armstrong sought to replicate the experience of being in the mountains. ‘The solemnity also – and frequent awfulness of the scenes one meets with – excite feelings and reflections which may with all sobriety be described as tending to produce a moral and intellectual elevation, corresponding to the physical elevation of the body.’ As the years went by, he acquired more and more land along the Ouseburn and moulded the landscape to resemble his ideal of nature. It was in this form that he now passed on the dene to his fellow citizens.

After the opening of Armstrong Park, the royal family and their retinue were entertained by members of the city corporation at nearby St George’s Hall, where lunch was followed by speeches and toasts. It was the turn of Newcastle’s radical Liberal MP, Joseph Cowen – editor and proprietor of the Newcastle Chronicle, and an old adversary of Armstrong – to take centre-stage.

Among his many provocative acts, Cowen had backed the strikers during the bitter engineers’ dispute of 1871 – when Armstrong had led the employers to defeat over the issue of the nine-hour working day – but, despite their political differences, a mutual respect had since grown up between the two men. Cowen was a controversial choice as speaker. Not once did he mention the royal guests; instead, he proposed a toast to ‘the industries of Tyneside’ and went on to deliver a paean to Northumbria – her history, her achievements, and the enterprising character of her people. In a climax that must have astonished many of his listeners, the politician ended his speech with a breathtaking tribute to his former opponent.

‘No name can be more appositely associated with northern industry and public spirit than that of the founder of Elswick, who has cast his thoughts into iron, invested them with all the romance of mechanical art, and achieved wealth almost beyond the dreams of avarice,’ proclaimed Cowen. ‘But he does not live for himself alone. He is happy when others can share in his bounty. Self-prompted, self-sustained, and, as regards his present profession, self-taught, he has worked his irresistible way through a thousand obstacles, and become one of the ornaments of his country when his country is one of the ornaments of the world.’ The MP then reflected on the unique relationship between Armstrong and the people of Newcastle: ‘He has interwoven the history of his life with the history of his native place, and has made one of the foundations of its fame the monument of his virtues. He has shown how the lofty aims of science and the eager demands of business can be assimilated, how the graces of social taste and embellishment need not be sullied by vulgar prodigality.’

Despite the audacity of its theme, Cowen’s speech was received by loud and prolonged cheering, according to The Times. But Armstrong himself struck a discordant note in his response – with a veiled allusion to a backstage row with the organising officials – when he lamented that, since so many events had been included in the programme, there would be no time for the royal party to visit his factories at Elswick: ‘An inspection of our places of industry which omits a view of the Elswick Works is rather like the play of Hamlet with the part of the prince left out.’ He was determined that his guests should at least have a view of Elswick from the river.

That afternoon, the Prince and Princess of Wales inaugurated the Natural History Museum at Barras Bridge – a project spearheaded by the naturalist John Hancock and backed financially by many of Newcastle’s leading citizens. The new building contained what was reckoned to be the most important collection of birds in the British Isles, including a specimen of an extinct great auk, as well as outstanding geological collections and a herbarium of British plants. It also provided a home for drawings of birds and animals by the engraver Thomas Bewick, and collections of fishes, mammals, reptiles, insects, fossils, and shells.5 Moving on to the Free Library in New Bridge Street, the Prince of Wales formally opened its reference department.

As they returned to Central Station to board the train to Rothbury, members of the royal party might have spotted, a short distance to the left of the station portico, the restrained Neoclassical façade of the Lit & Phil building, where more than 40 years earlier Armstrong had demonstrated in front of rapt audiences some of his first inventions, including a hydroelectric machine and a hydraulic crane. As a member of the Literary and Philosophical Society since 1836, and its president since 1860, he had attended and conducted debates there on all manner of topical subjects, contributed to the society’s vast and valuable collection of books, and put up the funds to build a 700-seat lecture theatre.

It was those early adventures in science and engineering that had captured the imagination of a knowledge-hungry public, invested the young Armstrong with a mysterious, otherworldly aura – and won him, at the age of 35, a fellowship of the Royal Society. John Wigham Richardson, who went on to found Swan Hunter shipbuilders, was growing up in Newcastle in the early 1840s and remembers being taken to see Armstrong deliver a lecture at the Lit & Phil: ‘One dark night in the Christmas holidays, our father took us four elder children to see Lord Armstrong (then Mr William Armstrong, solicitor) exhibit his electrical machine … It was a weird scene; the sparks or flashes of electricity from the machine were, I should say, from four to five feet long and the figure of Armstrong in a frock coat (since then so familiar) looked almost demoniacal.’6

During the final stage of the royal visit, Armstrong would have the chance to show off some of his greatest achievements to his future monarch – and he intended to seize it with both hands. But, before that, the royal family were looking forward to another sumptuous dinner at Cragside, from where they would observe the spectacular fireworks display, complete with bonfire, to be held at Cow Hill on Newcastle’s Town Moor, 30 miles away.

Next day, at Fish Quay, the royal party joined the chairman and officials of the River Tyne Commission on board Pará e Amazonas, a palatial paddle-steamer built by Andrew Leslie of Hebburn to carry passengers on the Amazon, and lent specially for the occasion. In attendance were nearly 30 other gaily decorated steamers carrying Tyneside dignitaries and their hangers-on. Rather than heading east towards the sea, Pará e Amazonas first steamed upriver for a mile to offer its passengers a good view of Elswick Works, where, as the prince could see, a shipyard was under construction beside the long-established engine works and ordnance works. By the end of that autumn, the keel would be laid down of the first Elswick-built warship, the torpedo cruiser Panther, commissioned by the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

Armstrong’s gilded business career had recently entered a new phase with the formation of Sir W. G. Armstrong, Mitchell & Co., a public company that cemented the long collaboration between the Armstrong firm and that of Charles Mitchell at Low Walker in Newcastle’s East End. Traditionally, Elswick Works had manufactured guns for warships built at Mitchell’s yard – but a new era had begun in 1876 with Armstrong’s building of the Swing Bridge between Newcastle and Gateshead, replacing an 18th-century stone bridge that had barred the passage of ships upriver. Driven by steam-powered hydraulic machinery that allowed it to swivel horizontally on a central pier, so that vessels could pass either side, the bridge had enabled the construction of ships at Elswick, 12 miles from the sea. The Tyne navigation had also been massively improved by dredging, and there were plans afoot to remove an entire island, known as King’s Meadows, from the centre of the river opposite the works.

Described only three years later by the politician Lord Randolph Churchill as ‘almost one of the wonders of the world’, the Elswick Works was even then undergoing a huge expansion. In 1884 it employed fewer than 5,000 people; by 1900, the Armstrong workforce would have grown fivefold. During the last decade of the 19th century, Armstrong Mitchell would periodically occupy first place in the league of British shipbuilders.7

Having turned around at Elswick, Pará e Amazonas led the long line of steamers back downriver, passing under Robert Stephenson’s High Level Bridge and through the Swing Bridge to be greeted by a crowd estimated to be around 80,000 on the Newcastle quayside. ‘On the high roofs of the houses, on the perilous tops of the most lofty chimneys, too, adventurous persons had perched,’ recorded The Times. ‘Wharves, wherries, the roofs of sheds, and the masts of ships, all were occupied; and even the pinnacle of the massive 80-ton crane carried its human burden. Everywhere the enthusiasm was unbounded. There was a continuous roar of cheering from the banks as the royal craft sped on.’ On the south bank of the river at Hebburn, more than 1,000 children were seen sitting on the side of a hill in a pattern based on the design of the Prince of Wales’s feathers; as the line of steamers approached, the children shouted and cheered, each vigorously waving a single white handkerchief.

Soon after two o’clock, the royal procession arrived at the deep-water dock at Coble Dene, nearly nine miles from the Newcastle quayside, where it was surrounded by hundreds of small boats heavy with sightseers. Although it had cost £740,000 to build, the new dock was a triumph of the Tyne Improvement Commission, which had striven for more than 30 years to upgrade the river in order to maintain Tyneside’s pre-eminence in the shipping world. Their success had been highlighted by Joseph Cowen the previous day: ‘Three centuries ago the Tyne was the eighth port of the kingdom. Now it ranks second in number of ships that enter it, third in the bulk of its exports, and first in the universality of its trade.’

One of the commission’s first great works had been the erection of two piers at the mouth of the river, which would eventually measure lengths of 3,000 feet (north pier) and 5,500 feet (south pier) respectively. Until 1860 there had been a sand bar at the entrance to the river, which gave a depth of only six feet at low water, and the entrance to the harbour was narrow and tortuous. Since then, 72 million tons of sand had been dredged, with the dredging carrying on at the rate of about 100,000 tons per week. The dock at Coble Dene had a depth of 30 feet at high water on a spring tide – a greater depth than any other dock on England’s east coast. A large staith had been constructed, on each side of which were four spouts for loading coal, meaning that coal could be taken on board waiting ships at a rate of 800 to 1,000 tons per hour.

At the west side of the dock was a warehouse for storing up to 40,000 quarters (500 tons) of grain and fitted with the most modern hydraulic machinery available. The dock had a tidal entrance 80 feet wide and a lock entrance 60 feet wide, each fitted with gates made of ‘greenheart’ oak and operated hydraulically – again making use of one of Armstrong’s earliest and most far-reaching inventions. Indeed, everywhere on the river, and in a myriad other places around the globe – from coalmines to railway stations to great ports – were visual manifestations of Armstrong’s marvellous achievements in the field of hydraulics. The phenomenon was captured in a memoir by Evan R. Jones, who had served as American consul in Newcastle from 1868 to 1883: ‘For ten years of patient industry Armstrong thought and wrought to perfect and realize his idea. Now the freights of nations are swung by his crane. His hydraulic machinery is found on every mart of commerce in the civilized world.’8

The Prince of Wales named the new dock Albert Edward and declared it open, whereupon lunch was served in a pavilion on the west side of the dock entrance. Afterwards, remarking on the indelible impression made by the Swing Bridge, the Prince expressed the hope that a similar bridge might one day be built across the Thames near London Bridge to serve the Port of London.

Reboarding Pará e Amazonas, the royal party led the line of boats to the mouth of the river, where there was time for a close inspection of the massive piers. As the steamer approached the landing stage on the north pier, the Tynemouth Life Brigade impressed the audience with a hair-raising demonstration of its rescue work. Landing on the lower part, the visitors were taken up to the higher level in an improvised carriage and drawn by a small locomotive along the wagon way of the pier to a platform erected in the shadow of the old Tynemouth Priory and Castle. After another round of adulatory speeches, the princes and princesses were conveyed through the crowded and festooned streets of Tynemouth to the station, where a train was waiting to take them back to Rothbury.

The royal family’s momentous visit to Cragside ended very much as it had begun, with a splendid formal dinner in advance of the departure by rail to Edinburgh the following morning. However, the visual record of those three days in August – a series of vivid watercolours by local artist Henry Hetherington Emmerson – portrays an atmosphere that is far from formal. Although he was the guest of a nouveau riche industrialist rather than someone of ancient lineage, the Prince of Wales showed no snobbery in his dealings with Armstrong. One of Emmerson’s paintings shows the prince and his two sons sitting in relaxed fashion on the terrace at Cragside, dressed in easy country garb – one smoking, another holding a local newspaper – all listening intently to their host’s words of wisdom. The Prince of Wales had inherited some of his father’s passion for scientific enquiry and engineering innovation – and Armstrong was the very embodiment of all that was new and exciting in the world of technology. In another painting, Emmerson depicts Armstrong in his library in the congenial company of Princess Alexandra and her three daughters. In a fatherly guise – which throws into relief his own childlessness – Armstrong points out to the young princesses an item of interest in a book. Again, even in a royal milieu, it is he who is the centre of attention.

Despite the thrills they had experienced in Newcastle and along the Tyne, it was the magician’s palace that had most entranced the royal visitors. Invited to taste the fruits of their host’s personal Xanadu, they liked what they saw and succumbed to its delights. Not least among the attractions of Cragside, it was acknowledged, were the extensive rock gardens, in which Lady Armstrong’s creative hand was everywhere revealed. Cloaking almost five acres, much of it consisting of precipitous slopes, they took their character from the crags above the River Coquet and the Debdon Burn. Almost all the rocks and stones which make up the three gardens had been manoeuvred into place by men using only levers and pulleys. Local fell sandstone had been collected from the surrounding moors and placed to show its weathered sides, and cascades were included in the designs to the north and west of house to introduce movement and the sound of water. Among the plantings were thousands of heaths and heathers, ferns, azaleas, and numerous alpine species. Between them, the Armstrongs were reckoned to have planted on the Cragside estate more than seven million trees and shrubs.

Three years after the royal visit to Newcastle, in Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee honours of 1887, Sir William Armstrong was raised to the peerage as Baron Armstrong of Cragside. However, some people muttered, as some always would, that Armstrong’s great wealth had been wrung from the blood and sweat of thousands of men less fortunate than himself, whose demands for improved working conditions he had cavalierly dismissed. His fiercest critics would later argue that Armstrong himself deserved nothing but contempt as a robber baron and a merchant of death – a man responsible for creating, manufacturing, and selling to all the leading nations on earth some of the most ferocious killing machines the world had ever seen.

Notes

1. From a BBC radio programme marking the opening of Cragside by the National Trust on 5 June 1979.

2. This and many other details of the royal visit of 1884 are drawn from the Record of the Visit of their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Wales to Tyneside, August 1884, compiled by the Town Clerk of Newcastle upon Tyne and published by Andrew Reid, Newcastle, 1885.

3. Newcastle Weekly Courant, 22 August 1884.

4. The Times, 20 August 1884.

5. ibid.

6. Richardson, John Wigham (1811) Memoirs 1837–1908, Glasgow: Hopkins.

7. Warren, Kenneth (1989) Armstrongs of Elswick: Growth in Engineering and Armaments to the Merger with Vickers, London: Macmillan.

8. Jones, Evan Rowland (1886) Heroes of Industry, London: Sampson Low.

2

The Kingfisher

It all began with water. Even as a young boy, William Armstrong was inexorably drawn to the streams and rivers near his home in the rugged, hilly countryside east of the booming coal town of Newcastle upon Tyne. From an early age his passion was fishing, and he spent many happy hours with rod and fly, thigh-deep in the fast-flowing burns of Northumberland in pursuit of the elusive trout. By his own account a ‘weakly’ child, prone to recurring chest ailments, William also put great faith in the curative powers of water – a faith that stayed with him throughout his long life. During a recuperative fishing trip to Rothbury in 1843, he wrote reassuringly to his wife, Meggie: ‘I am now getting well as fast as can be. I have been almost continually in the water this glorious day and there’s nothing does me so much good.’

William George Armstrong was born in the hamlet of Shieldfield on the edge of Pandon Dene on 26 November 1810, eight years after the birth of his sister, Anne. The family home was a three-storey terraced house in Pleasant Row with a back garden running down to the dene. Like many of the deeply cut valleys that fed their waters south into the mighty Tyne, by the mid-19th century Pandon Dene had fallen victim to the eastward expansion of Newcastle, and then been severed by a railway embankment. ‘Year by year Newcastle goes on filling up the denes and valleys which intersect her,’ lamented a contemporary chronicler.1 ‘One after another they disappear, and the picturesque undulation of the old town promises in time to give way to the level monotony of a flat surface.’ But in the early part of the century, when Anne and William were growing up there, the dene was a beguiling place, with the burn winding through it and the hum of watermills mingling with the sound of varied birdsong. ‘The mass of apple-blossom and the teaming luxuriance of the foliage which covered the banks, the little summer-houses in the trim gardens, and the winding pathway from the town to the Shieldfield, formed a picture of rare sylvan beauty.’ The original ‘Shield Field’ was the place where English soldiers would traditionally muster in preparation for their many battles against the Scots. Part of the attraction for children was the ruins of a fort built there in 1644, during the Civil War, to defend the Royalist garrison in the town against the Scots Covenanters. King Charles I had been allowed to play golf on the Shield Field during his captivity in Newcastle in 1646.

A mile or so north-east of Shieldfield, at Jesmond, was another, equally enchanting dene that would prove more resistant to urban sprawl – and which, as the 19th century progressed, would lure more and more of the prosperous families of Newcastle to create homes and gardens along its ridges. With its steep and densely wooded banks giving way to wide grassy clearings, Jesmond Dene follows the course of the meandering Ouseburn for two miles between South Gosforth in the north and Jesmond Vale in the south. The river either flows purposefully through old woodland or gathers pace briefly in rapids and waterfalls, once used to power the corn and flint mills lining the valley. Featuring unusual rock formations, stepping stones, and a variety of bridges, the dene has a magical quality. Although in Armstrong’s day it was flanked by mines and small industrial works, even then it offered a wonderful respite from the urban world. The combination of its proximity to the centre of Newcastle and its aesthetic appeal made it a desirable place of residence for the emerging middle classes, and an influential community within a community evolved there. It was in this physically and intellectually alluring environment that William Armstrong would set up his first home in the mid-1830s.

During the early years, however, it was the seductive charms of Coquetdale, 30 miles to the north, which exerted the strongest pull on young William. His father’s friend Armorer Donkin, a rich bachelor, had a country home at Rothbury on the River Coquet, and the Armstrong family were frequent visitors. Donkin – an early member of Newcastle’s Literary and Philosophical Society – numbered among his vast circle of friends the radical journalist James Leigh Hunt. Destined to play a seminal role in Armstrong’s brilliant career, Donkin was ‘most generous in the manner as well as the amount of his sacrifices’, wrote Leigh Hunt, describing him as ‘one of the men we love best in the world’.2

Donkin and the Armstrongs, father and son, fished together on the Coquet and young William developed a talent for the sport. Among his mentors was Mark Aynsley, a young Rothbury shoemaker so skilled in the art of dressing flies that they would nearly always ‘fetch’ a Coquet fish. ‘I was scarcely ever away from the waterside and fished from morning till night,’ Armstrong admitted later. ‘They used to call me the Kingfisher.’3 He confessed to a fondness for poaching, which he always did alone, his favourite stretch of water being on the nearby Brinkburn estate, whose fish were, in theory, carefully protected: ‘I have many a time crept under the bushes close to the house and filled my creel.’ Even during the harsh northern winters, when the rivers froze over, he couldn’t keep away from the water, and he proved also a competent skater, who with his tall, slim physique and arresting good looks was said to have ‘carved some graceful figures on the ebony surface of the Tyne’.4

To Armstrong, these childhood experiences were full of joy. ‘I believe that I first came to Rothbury as a babe in arms, and my earliest recollections consist of paddling in the Coquet, gathering pebbles from its gravel beds, and climbing amongst the rocks on the crag. For many years I annually visited Rothbury with my parents and under well-known local celebrities I learned to fish. The Coquet then became to me a river of pleasure. As I grew up, I extended my explorations of it from its mouth to its source, and acquired an admiration for its scenery which has been a source of enjoyment to me through all my life.’

William Armstrong’s love affair with water – which only deepened as he grew older – and his desire in general to commune with the natural world, had an intensely practical side: a fascination with channelling elemental power to useful ends. This sprang from his wish to know how everything worked and, once he had found out, to improve on it – a pursuit that was given free rein during the long periods, sometimes months on end, when he was kept at home because of ill health. From as young as the age of five or six, William delighted in getting hold of old spinning wheels and other domestic items, and he would construct from them mechanical devices that could be set in motion by primitive pulleys, made from weights hung on strings from staircase railings. His interest in toys – which, whenever possible, he would take to pieces – depended on how far they satisfied his curiosity. His very early inventions included a new basket for fishing bait, designed to preserve minnows at the proper temperature.

One of William Armstrong’s favourite excursions as a child was to the shop of old John Fordy, who did joinery work for his maternal grandfather, the Walbottle colliery owner William Potter. With Fordy’s help, he would make fittings for his miniature engines or earnestly copy the joiner’s work, acquiring a skill in the use of tools that proved invaluable in later life. Armstrong later told his friend Thomas Sopwith that his childhood had been ‘a continual study of electricity, chemistry and mechanics’ – none of which would have been taught at school.

More than fifty years before the introduction of compulsory elementary education, there was already a number of thriving schools in the Newcastle area for the lower and middle classes, including charity schools, Sunday schools, and private academies such as the highly regarded Bruce’s Academy in Percy Street, attended by the future railway engineer Robert Stephenson, Armstrong’s near-contemporary. Armstrong’s early education at a private school in Whickham, west of Gateshead, was greatly supplemented by the intervention of his ambitious father, who had proved himself a skilled mathematician and had begun to amass a vast collection of books. And, like Robert Stephenson – who had been encouraged to assiduous study by his brilliant but illiterate father, George – he would have immersed himself in the library that formed a core part of Newcastle’s learned society, the Lit & Phil.

By 1826, when Armstrong was sent to grammar school at Bishop Auckland in County Durham, his passion for mechanics was clear, and his enthusiasm for experimentation was growing. But the 15-year-old boy would have little opportunity to pursue those interests at school, where instruction was confined to ‘reading English, writing and accounts’ – in addition to the classics, a subject particularly valued by his father. A contemporary report reveals that there were, on average, 55 boys in the school, about 10 of whom received instruction in the classics. Classicists were expected to pay fees of 10s 6d a quarter.

In Bishop Auckland, Armstrong lodged with Reverend Robert Thompson, master of the school since 1814, and in one notorious incident smashed a window of a neighbouring home while testing a home-made crossbow with missiles fashioned from the stems of old tobacco pipes. The renegade’s school career survived the incident, but it is an example of how his academic studies were clearly not sufficient to satisfy his curiosity. Years later he wrote to his friend Stuart Rendel about tactics for making time pass more quickly: ‘At school before the holidays I used to try a stick notched to correspond with the number of remaining days – one notch was obliterated every morning until the happy day of release arrived.’ Armstrong’s frustration may have had something to do with the master’s lack of commitment to his pupils. The governors later found that, during a particular five-year period, Mr Thompson had ‘rarely attended the school’, criticising the poor standards that had resulted.