Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

William Dargan's career began in Wales on the Holyhead Road, working under the famous Scottish engineer, Thomas Telford. He went on to build roads, railways, canals and reservoirs, developed hotels and the resort towns of Bray and Portrush, laid out Belfast harbour, ran flax and thread mills and reclaimed vast tracts of farmland in Derry and Wexford. He operated canal boats and cross-channel steamers, constructed several canals and railways in England and in 1834 built Ireland's first railway from Dublin to Dun Laoghaire. There is hardly a town in Ireland untouched by William Dargan. Alone he funded and constructed the 1853 Art-Industry Exhibition on Dublin's Merrion Square as a boost to a country recovering slowly from the effects of the Great Famine just five years before. The National Gallery, raised largely in tribute to him, has a Dargan Wing and his statue stands in its grounds. Despite these achievements Dargan was a modest man. Several times he declined a peerage, a seat in parliament and even the baronetcy offered by Queen Victoria when she came to take tea at Mount Anville, his south Dublin mansion. This fascinating book, complete with over thirty archival photographs, draws on a range of original material and sources, much never seen in print before, to present an all-round portrait of a dynamic and engaging figure showing how his energy and abilities laid the foundations for Ireland's later prosperity. The story of Dargan and his era will inform and uplift, evoking wider appreciation of a true patriot and an honourable man who did so much for his country.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 504

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

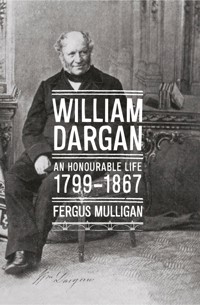

WILLIAM DARGAN

An Honourable Life 1799–1867

Fergus Mulligan

A portait painting of Dargan in 1854, by George Francis Mulvany, first Director of the National Gallery of Ireland (courtesy CIÉ).

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

List of Abbreviations

BBC&PJRBallymena, Ballymoney, Coleraine and Portrush Junction Railway

B&BRBelfast & Ballymena Railway

B&CDRBelfast & Co. Down Railway

BJRBanbridge Junction Railway

B&LJCBirmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal

CB&PRCork Blackrock & Passage Railway

CIÉ Coras Iompair Éireann

DART Dublin Area Rapid Transit

D&BJRDublin & Belfast Junction Railway

D&DRDublin & Drogheda Railway

D&ERDundalk & Enniskillen Railway

D&KRDublin & Kingstown Railway

DL Deputy Lieutenant

D&WRDublin & Wicklow Railway

DW&WRDublin Wicklow & Wexford Railway

EGMExtraordinary general meeting

GSH Great Southern Hotels

GS&WRGreat Southern & Western Railway

ISERIrish South-Eastern Railway

KJRKillarney Junction Railway

L&BRLiverpool & Bury Railway

L&CRLondonderry & Coleraine Railway

L&ER Limerick & Ennis Railway

L&FRLimerick & Foynes Railway

L&MR Liverpool & Manchester Railway

L&NWR London & North-Western Railway

MGWRMidland Great Western Railway

M&LRManchester & Leeds Railway

N&ARNewry & Armagh Railway

N&ERNewry & Enniskillen Railway

NW&RRNewry Warrenpoint & Rostrevor Railway

P&DRPortadown & Dungannon Railway

RAISRoyal Agricultural Improvement Society

RDSRoyal Dublin Society

RERoyal Engineers

RHA Royal Hibernian Academy

RHSI Royal Horticultural Society of Ireland

RICRoyal Irish Constabulary

TCD Trinity College Dublin

T&KRTralee & Killarney Railway

UCD University College Dublin

URUlster Railway

W&LRWaterford & Limerick Railway

W&TRWaterford & Tramore Railway

WWW&DR Waterford, Wexford, Wicklow and Dublin Railway

Preface and Acknowledgments

Over many years I’ve studied the life and career of William Dargan, developing a great admiration and genuine respect for the kind of man he was and his achievements, even though he died eighty-five years before I was born. His way of living and working are admirable and were always marked by a sense of decency and fair play. Also the scale of his achievements in developing the dormant Irish economy through transport infrastructure and many other enterprises has to a large extent been forgotten. Behind this cold economic terminology is the reality that Dargan provided many thousands with a livelihood, especially during the dark days of the Famine. However, we should not confuse humanitarian qualities with softness: Dargan could display steel-like attributes when necessary.

The example of a life well lived is relevant in all eras but especially so in difficult times such as the present. Openness, honesty and fair dealing are universal, timeless qualities and comprise a valid role model for anyone in business even if they have been clearly absent from many of our financial and political institutions in recent years. The life of William Dargan has a resonance and a relevance even for our day.

Sometimes he has seemed a hard man to track down. On occasions I found myself in libraries, archives or company record repositories, trawling through a vast, almost indecipherable nineteenth-century minute or letter book trying to locate a vital piece of information on a Dargan project secreted somewhere within. A board or committee meeting’s ‘rough minutes’, as they were called, the first draft, written in haste in spider scrawl and without an index of course are often the only company records to survive. To the occasional alarm of other researchers I’ve tried communicating with Dargan at such times, appealing to him to help me find the right page along these lines: ‘If you want me to write your life story, you’d better help me.’ Then, as people used to do in a former era when seeking guidance from the Good Book, I would open the huge volume of minutes at a random page. And there, every single time, without fail, guaranteed, would be … nothing of any use or interest whatsoever.

Despite Dargan’s lack of celestial cooperation in the area of research he would still be the first person in my line up of historical guests at an imaginary dinner party and my list of questions to him would be as long as the phone book.

The Greatest Train Journey of All

In researching Dargan I’ve sometimes thought of life as a train journey. When you first step aboard, the train seems to be full of old people and it moves very slowly. It makes lots of stops and you have to stand as all the seats are occupied. But at each station some people get off and others get on, so that at times the train can seem crowded but at others quite empty and you have no trouble finding a seat. As the journey continues the average age of the passengers appears to decrease and at the same time the train starts to speed up. After a while you look around the carriage and realize not only are most passengers younger than you but you’re actually one of the oldest. Occasionally you seek out a friend or a relation only to discover they got off several stations back.

And then suddenly it’s your stop. No matter that there’s something you just have to do, there are people you meant to contact, you really want to finish the book you’re reading or you’d rather chat to your fellow travellers than face the disruption of alighting at a strange station in the middle of nowhere. It’d be much easier if this was the terminus and everyone alighted together but your journey isn’t like that and the fact that lots of others before you have left the train at their destination is little comfort. Your ticket is only valid as far as here, so leaving everything including the comfort and warmth of the train behind you, reluctantly, you get up from your seat, walk to the door and step from the train onto a darkened platform. You’ve never felt so completely alone and barely notice people at the carriage windows waving goodbye as the door behind you swings shut and the train moves off slowly into the night. You have no choice but to turn and face … what? This is where my imagery fails.

If you’ve tried to lead a decent life, and even if you’ve failed, you’ve nothing to fear when you leave the train, no matter what awaits you on the platform. And that’s one of the reasons I wrote this book about William Dargan: to present a pen portrait of someone who was honourable, fair-minded and hard-working, a man who changed the face of Ireland and left the world a better place than he found it.

Buíochas

Lots of people helped with this book and I received great encouragement from many different quarters. My friend Martin Nevin of the Carlow Historical and Archaeological Society, who was enthusiastic from the start about a life of William Dargan, has done much to research and preserve the memory of Dargan in his native county and farther afield and has always been most generous in sharing his time and his knowledge.

Prof. Louis Cullen was very supportive and would often greet me with an interrogative: ‘And how is Mr Dargan?’ before gently demolishing my excuses for not completing this book. Prof. David Dickson, my PhD supervisor at Trinity College Dublin, always encouraged me to publish, while the Dargan family, the most patient people on the planet, were ever supportive and encouraging. While researching in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland I often met the late Herbert Dargan SJ, one of William’s great-grandnephews, then based in Belfast. His brother, the late Dan Dargan SJ, lived in retirement in Ranelagh and would occasionally phone me to suggest a possible research area and to inquire directly how the book was progressing. Their niece, Mary Dargan Ward, who rightly has immense pride in her great-great-granduncle, has always been positive and interested in nuggets of information I managed to discover about her illustrious ancestor.

Grants from the Grace Lawless Lee Fund at Trinity College Dublin helped greatly when travelling to the UK for research purposes. At a recent critical stage, when the writing molehill was truly a mountain, I spent two very pleasant weeks during a cold, crisp winter at Villa Palazzola in the Alban Hills outside Rome where free of all distractions and excuses the peace and calm of that beautiful place were so conducive to writing. My thanks to Mgr Nicholas Hudson and Joyce Hunter for facilitating those productive visits. I am grateful to Geraldine Finucane, Group Secretary and the Board of CIÉ for allowing me to reproduce the fine portrait of Dargan by George Mulvany, and to Olivia O’Leary, a famous Carlovian like Mr Dargan, for performing the launch.

My brother, John Mulligan, willingly drove me around Anglesey to locate Mr Dargan’s early handiwork in north Wales and we spent many pleasant hours with Tara Dog exploring and photographing Dargan’s canal in Staffordshire and visiting the church at Adbaston where he and Jane were married. Among people deserving a special mention are: Dr Andy Bielenberg, University College Cork, Bruce Bradley SJ, John Callanan, Engineers Ireland, Prof. Ron Cox, Trinity College Dublin, the late Dr Maurice Craig, Kevin Curry, Brian Donnelly, National Library of Ireland, Brian Gilmore, Rob Goodbody, the late Charles Hadfield, Richard Harrison, Mary Kelleher former RDS Librarian, Barry Kenny, Iarnród Éireann, Kathleen Kinsella, Bray, my cousin Dr John Logan formerly of the University of Limerick, the late Lord Meath, Jenny Muddimer, St Michael’s church, Adbaston, Frederick O’Dwyer, Cormac Ó Grada, University College Dublin, Sr Maire O’Sullivan, Mount Anville convent, Ray O’Sullivan jnr Genprint, Joanna Quinn, RDS Library, Peter Scott Roberts, Holyhead Maritime Museum, Alexander Smeaton, Dublin City Libraries, the late Mark Tierney OSB, Glenstal Abbey, Ray Thomas, St Mary’s church, Market Drayton, Dr W.E. Vaughan, Trinity College Dublin and Gerard Whelan, RDS Library.

That the writing of this book took so long is no-one’s fault but mine and the fact that that some people in the above list have gone to a better place shows how extended its gestation has been.

I also want to thank the staffs of the following archives, libraries, companies and institutions who willingly provided access to records and archival material in their care: Allied Irish Bank Archives, Bank of Ireland, Belfast Harbour Commissioners, Bray Heritage Centre, British Library, London, British Library of Political and Economic Science, London, British Newspaper Library, Colindale, Caledon House, Co. Tyrone Carlow County Library, Carlow Historical and Archeological Society, Coras Iompair Éireann Archives, Cork City Archives, Department of the Environment, Belfast, Dublin Chamber of Commerce, Dublin City Archives, Dublin Diocesan Archives, Dublin Port Archives, Fingal County Council Archives, Engineers Ireland, Glasnevin Cemetery Archives, Glenstal Abbey Archives, House of Lords Record Office, Institution of Civil Engineers, London, Irish Architectural Archive, Irish Railway Record Society, Kilruddery House, Linen Hall Library, Belfast, Liverpool Record Office, Market Drayton Library, Shropshire, Marsh’s Library, Dublin, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Mount Anville Archives, National Archives Dublin, National Archives London, National Gallery of Ireland Archives, National Library of Ireland, Picton Library, Liverpool, Probate Registry, York, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, Religious Society of Friends, Dublin and London, Royal Archives, Windsor Castle, Royal Dublin Society Archives, Royal Irish Academy, Royal St George Yacht Club, Salt Lake Family History Centre, Utah, Shropshire County Record Office, St Alban’s parish, Merseyside, St Patrick’s College, Carlow, Trinity College Library and Manuscript Room, Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, University College Dublin Library, Wicklow County Library.

A glance at the contents will indicate that this book covers Dargan’s life in a thematic way focusing on the major projects he undertook and the key events of his life. In doing so it is broadly but not strictly chronological. I hope this book will encourage others to come forward with their research findings and new information about Dargan the man. All the usual E&OE apply and all amendments and updates about William Dargan will be gratefully received at [email protected].

For years when pointing out a building, a canal, a railway, a road or a viaduct my children’s eyes would glaze over as they intoned in a monologue: ‘Yeah, yeah, Mr Dargan built it.’ And so I dedicate this book to my wife Eveleen and our children Matthew, Clare and Conor, who have tolerated if not shared my interest in William Dargan’s life.

Fergus Mulligan

1 April 2013

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The Publisher would like to thank for their painstaking work his editors Djinn von Noorden and Fiona Dunne, and Marsha Swan for her typesetting and page design.

1. Introduction

William Dargan is arguably the greatest Irishman of the nineteenth century. His name is often recognized yet his life and achievements are still only vaguely acknowledged. In the Republic there is one bridge named after him, the slightly overstated Luas bridge at Dundrum, despite calls to name it after a local politician from people who do not realize it is already called Dargan Bridge. His name is incorrect on the bridge plaque and his dates are out by ten years.

Forty metres from where I write is the embankment of a railway line Dargan built 160 years ago, still solid as ever and now a busy rail corridor for the Luas. That is a fair achievement by any reckoning and hard evidence of just one of his great achievements.

The major event in nineteenth-century Ireland was without doubt the Great Famine of the 1840s. No one is sure of the full extent of the deaths during and after an Gorta Mór: the authorities kept few records of pauper deaths, and a million dead and two million emigrants is probably as close as we can get to horrible reality. Two of the leading figures of nineteenth-century Ireland, Michael Davitt who founded the Land League and Charles Stewart Parnell, were both born in 1846 at the start of the Famine, while Daniel O’Connell, the Liberator, died in 1847 just as it reached its peak. By contrast Dargan’s career as an engineer and entrepreneur was at its pinnacle in the years just before, during and after the Famine. At this time he claimed to have 50 000 people working on his various projects; possibly an exaggeration to include subcontractors he employed. But even if the figure is halved, it means 25 000 men earned a living on Dargan projects and if each supported four other people (a modest estimate), 100 000 relied on wages from William Dargan to survive during the bleak years of the 1840s. He gave this economic lifeline to so many people who would otherwise have starved.

Political figures, especially those who died for freedom, tend to be better remembered in Ireland than the few who employed the destitute and advanced the economic development of the country. One of the aims of this book is to show just how unique was Dargan’s contribution to Ireland and to suggest that he, as much and probably more than any other figure in nineteenth-century Ireland, deserves that overused and sometimes abused title of patriot.

Dargan’s Key Principles

Although most of Dargan’s own records, accounts and business papers have not survived and there are irritating gaps in his curriculum vitae it is still possible to say a lot about the man and his business methods. He came from a modest farming background in Co. Carlow and his transition from an ordinary rural upbringing to becoming one of the richest men in Ireland was phenomenal. What marks Dargan out from many other successful entrepreneurs and industrialists is that he achieved this great success using his own talents and skills, with the benefit of some useful contacts at the start of his career but without inherited wealth and most important without exploiting his workmen. His success was built on his reputation: the companies that gave him contracts and the men he employed trusted him to behave fairly. This is not to say he did not have difficulties with some projects or that every one was a total success but his sense of business ethics and fair dealing put him ahead of many of his rivals. This is a hard role to adopt in any era but even more so at the dawn of the industrial revolution.

Dargan’s decency towards his men won their loyalty and was a major factor in his being able to complete his projects satisfactorily. He paid wages on time but if his men went on strike (combination being an illegal act at the time) he could be ruthless, dismissing the strikers or in some cases prosecuting them. If a client treated him badly or refused to pay what he felt he was due he was very direct in saying as much and taking every step to recover what he was owed. Underneath that genial benevolence was a layer of steel.

An example of this forthright management style is the way Dargan handled the widespread system known as ‘truck’, on-site provision shops run by some contractors. Such hucksters often sold over-priced, shoddy goods, including alcohol and food items and by extending credit ensured their labourers were caught in a perpetual web of debt. Dargan recognized truck had some benefits for men working far from any town but the risks and problems outweighed the potential benefits and so he did not permit it. However, when building a section of the line to Cork in 1845 a Dublin paper criticized the wages he paid and accused him of exploiting his own men with truck. His letter unequivocally refuted the allegation, adding that over fourteen years as a contractor he had paid his workmen £800,000 in cash (see Chapter 5).1Dargan was clearly irritated by the accusation and his trenchant response is eloquent in its denial of the charges and his statement of policy as regards his workmen. It also indicates his financial muscle: £800,000 was a very large sum. There were no further such accusations against him.

This fairness and transparency in relations with his employees is mirrored in Dargan’s dealings with the companies who awarded him civil engineering contracts. Construction projects can be complicated and not every job went smoothly. However, Dargan managed to complete most of his contracts on time and within budget and even when this was not the case, measured negotiation nearly always resolved any major issues, with one or two notable exceptions.

An engraving of William Dargan by W.I. Edwards for the 1853 Catalogue to the Industrial Exhibition based closely on the portrait by George Mulvany.

A Giant Among Men

Dargan accomplished an extraordinary amount of work in his lifetime. He is known today mainly as a railway contractor (or civil engineer) and the mark he left on the country is huge. He built around 830 miles of railway in Ireland (1335 kms), a staggering amount, plus sections of line in Lancashire and Yorkshire. Before any railway opened in London he built the first public passenger railway in Ireland, the Dublin & Kingstown, now the DART line between Pearse Station and Dun Laoghaire. Farther afield, anyone travelling by train to Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Killarney, Tralee, Limerick, Athlone, Galway, Longford and Belfast is travelling on lines built wholly or mainly by William Dargan. We can add to this list other branch lines (most now closed) such as Cavan, Foynes, Tramore, Passage and several out of Belfast including Newtownards, Banbridge, Armagh, Ballymena and Portrush. Although the railway network in the north has been decimated and only a few of Dargan’s lines there remain open, without Dargan’s industrial muscle, who knows how long Ireland would have had to wait before these lines were built?

Yet Dargan did much more than just build railways. After constructing the road between Howth and Dublin – the final link in Telford’s great highway from London to Dublin – he built several canals, among them a section of the Newry Navigation with its magnificent locks, the Kilbeggan branch of the Grand Canal and the entire Ulster Canal connecting Lough Neagh to Lough Erne. He then ran barges on the Ulster Canal, which fed into the cross-channel port at Newry and from there ran steamers to Liverpool. He attempted to develop the linen and sugar industries, growing flax and sugar beet, he invested in hotels, he changed Bray from a wretched fishing village into a thriving, fashionable seaside resort, he reclaimed vast sloblands on the Foyle and in Wexford, turning them into fertile farmland, he ran a thread mill in Chapelizod, which at one time employed 900 people and he built canals and a brace of major railways in England.

The creation of the National Gallery of Ireland is largely the result of public demand for an expression of gratitude to Dargan for his work in proposing, building and funding entirely on his own the Art-Industry Exhibition of 1853. It was held on Leinster Lawn on ground now occupied by the Gallery.

In contrast to this great catalogue of achievements Dargan was a genuinely modest man. The Victorians had a distressing fondness for excessive rhetoric that often verged into humbug: the successful completion of a railway line elicited a squadron of public and private individuals eager to claim the credit. The celebratory dinner always included many tedious speeches and toasts to everyone from the monarch down to the station cat. Despite being the key person who brought the line into existence both literally as its builder and sometimes the chief financer, Dargan was usually among the last to speak. More often than not he simply stood up, wished the company every success, and sat down again. This was typical of the man: he was paid to do a job and he was glad it turned out well. Subsequently he declined many offers to take a seat in Parliament and steadfastly refused public honours, culminating in his courageous direct refusal of a baronetcy from Queen Victoria when she called to his house for tea one afternoon in 1853.

Given the nature of his work all over Ireland it is not surprising Dargan moved around a lot. The compilation of his addresses below taken from correspondence and various directories shows how much he travelled in the course of his career. Until 1851 some served as both home and office. All dates are approximate and overlaps are evident.2

A Famous Son of Carlow

Some years ago the Old Carlow Society decided to raise a plaque to the county’smost famous son and asked me to write the text and to unveil the plaque, a surprise and a great honour. The ceremony took place on the platform of Carlow station in September 1993 in the presence of William’s great-grand-nephew, the late Fr Daniel Dargan SJ and Mary Dargan Ward. It was a wonderful occasion and passing through Carlow station it still gives me delight to see the plaque on the station wall honouring this great man.

2. Dargan’s Early Life and Career

William Dargan was born at the cusp of the nineteenth century on 28 February 1799, a year after the bloody rebellion that took place throughout south-east Ireland. Dargan family tradition has it that two of William’s uncles, Thomas and Michael Dargan, were involved in that fatal and informer-blighted uprising and were tricked into going to Carlow town where the yeomanry, with their trademark brutality, seized and hanged them.1The name Dargan comes from the Irish Ó Deargain, the red-headed one.

Dargan’s Accent: Follow Me Up to Carla’

Despite the absence of recording equipment in the nineteenth century we can, with a degree of accuracy, hazard a guess as to William Dargan’s accent. Take the train from Heuston Station towards Waterford along the line he built so well and alight on the platform at Carlow. Walk down the town and stop in Main Street and wait till you see two local people aged forty-five or over and listen to their chat. If they’re Carlow people and they haven’t lived away from the town for any length of time, chances are you’re hearing an accent very similar to William Dargan’s.

Dargan’s Birthplace

Co. Carlow was and remains a prosperous part of the country with good farmland and a number of fine country houses. Some details of Dargan’s family background were published inCarloviana2with the location of the grave of William’s father in Killeshin cemetery. Patrick Dargan died in 1833, aged seventy-seven, and William’s mother, Elizabeth, who died aged forty-two in 1813, is also buried in this grave, as are four of William’s youthful siblings reflecting the high child mortality rates in those days. Among his other surviving brothers and sisters were Mary, Thomas, James, Elizabeth, Selina who is mentioned in his will (see Chapter 9) and Michael. Apart from his brother James who worked with him as a railway engineer little is known about this group. Similarly the family religion is uncertain; the fact that so many of his relations entered the priesthood, combined with events at the end of his life, make it likely he was born a Catholic.

Press Coverage in 1799

Finn’s Leinster Journal, one of the few local papers in Ireland at the time of Dargan’s birth, was published twice weekly in Kilkenny and circulated in Co. Carlow. The issue for 27 February to 2 March 1799 unsurprisingly has no mention of Dargan’s birth: the son of a tenant farmer would not merit inclusion. It did, however, carry London gossip, news of local outrages, continuing efforts to stamp out the 1798 rebellion and the winning numbers of the ‘English Lottery’ with substantial prizes of £20,000, £10,000, £500 and £50.Plus ça change.

William’s parents, Patrick and Elizabeth Dargan, were said to be relatively well-off tenant farmers with a holding of around sixty-one acres at Springhill and Ballyhide, Queen’s County (Laois).3In 1819 Patrick transferred the sixty-one-acre tenancy to his sons Thomas and William.4The question of William’s birthplace remains disputed as both Laois and Carlow claim him. The plaque unveiled at Carlow station by the Old Carlow Society states he was from Carlow while a similar but contradictory plaque at Portlaoise station claims him for Laois.5

In later yearsThe Irish Timescited his birthplace as Carlow, a location firmly rejected by the editor of theCarlow Sentinelwho said Dargan was born at ‘Spring Hill in the Queen’s County’,6close to where Martin Nevin of the Carlow Historical and Archaeological Society places it.

Those industrious genealogists, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (aka the Mormons), have listed Dargan’s birthplace in their universalInternational Genealogical Indexas Ardristan near Tullow, Co. Carlow. It is quite possible Dargan’s family moved from there when he was an infant, even to several different locations. One move may have been to Graiguecullen, a suburb of Carlow town west of the River Barrow and therefore in Co. Laois. Another possibility is that William may have lived with some of his relations. It was not uncommon for large families to divide their children among other family members to share the burden of rearing them.

Martin Nevin has made great efforts to locate the Dargan homestead but even he can only locate it approximately. The most likely location and the place where he grew up (but not necessarily where he was born) is in the townland of Ballyhide, Killeshin, Co. Laois, west of Carlow town and the River Barrow on the slopes of the Slieve Bloom mountains. It is possible the family lived in Crossleigh House, Ballyhide. The evidence for this claim is a land purchase Dargan made in 1850 through the Encumbered Estates Court of 101 acres owned by Lord Portarlington for £2114 9s.3d., a substantial sum even for a man as wealthy as he had become by then.7The land is good quality and the map accompanying the deed shows it is about half a mile wide and a quarter deep, divided into approximately seventeen small fields with two small houses.8By 1825 the tithe records do not list a single Dargan living in Ballyhide.

The Text on the Dargan Grave at Killeshin

The Dargan family grave at Killeshin graveyard, Co. Laois. William’s parents Patrick and Elizabeth Dargan and several of his infant siblings are buried here. Photo: Martin Nevin

IHS Gloria in Excelsis Deo Erected by Patrick Dargan in memory of his mother Giles Dargan who departed this life the 24th of April 1801 aged 76 years. Lord have mercy on their souls. Amen. And also his wife Elizabeth Dargan who departed this life December 24 1813 aged 42 years. And of the above Patrick Dargan who departed this life March 12 1833 aged 83 years. And of his children Michael Laurence Bridget and Patrick who died young.

The Barrow bridge at Carlow town with the distinctive castle that once guarded the river crossing. Dargan would have passed over this bridge many times.

Crossleigh House, Ballyhide. Co. Laois, where Dargan may have spent his early years.

The deciding factor must be that he described himself as from Carlow on more than one occasion, for example before a House of Commons parliamentary committee in 1845.9In summary, it is therefore likely that Dargan was born near Tullow, Co. Carlow, and moved to Graiguecullen, Co. Laois, outside Carlow town at an early age and then spent most of his youth at Ballyhide, also Co. Laois.

Encumbered Estates Court map showing the lands Dargan acquired when he bought his homestead in 1850.

Patrick Dargan’s holding was part of the estate of Lord Portarlington whose seat was Emo Court. From later events it appears William attracted significant patronage and that he and his family were well regarded by their landlord.

William was one of a large family. His brother James worked as a railway engineer and married Jane Walsh in the Anglican church of St Philip, Liverpool on 7 September 1839. He died in Limerick in 1854, aged forty. James had a son, also called James Dargan and another railway engineer and it is from him that William’s great-grand-nephews, the three Jesuit Dargans, were descended down to William Dargan SJ, Herbert Dargan SJ and Daniel Dargan SJ, all deceased, as well as Mary Dargan Ward, keeper of the surviving family records.10

A useful and rare source on Dargan’s early years is a manuscript version of theHandbook of Contemporary Biographypublished soon after 1853, in which the subjects edited or rewrote their own entry.11The handwritten author proof corrections survive in the British Library and we can be reasonably certain that Dargan made these corrections himself. The entry states that Dargan went to school in Graiguecullen.12He was said to be of strong physique, very speedy in drawing up a contract and could complete calculations rapidly and accurately; all characteristics that would serve him well in his later career. A government report throws some light on the possibilities.13

The Best Days of His Life: What Kind of Schooling Did Dargan Have?

The Appendix to the Second Report of the Commissioners of Education Inquiry Information provides data on schools in Carlow and Laois in the early nineteenth century. Though published in 1824, about ten years after Dargan finished his schooling, the report reveals a great deal about education in that era. Graiguecullen, east of Carlow town, had five stone-built schools, all fee-paying: three Catholic and two Protestant, with pupil numbers ranging from sixteen to seventy. The income of the master or mistress is recorded (£10 to £35 p.a.) but the only mention of a curriculum in the Appendix is whether or not the scriptures were read to the pupils. There is also an entry for Evaton, ‘a spacious mansion’, probably Everton House at Kelleskin (Killeshin) civil parish, a private RC boarding school with thirty-three male pupils under Master George Alexander Lynch, which cost £3000 to build. His income was a staggering £1280 p.a. By contrast, Master Patrick Byrne ran a school at Ardristan, east of Carlow, possibly Dargan’s birthplace. He taught thirty-eight RC boys and girls in a ‘miserable mud cabin’, surviving on an income of just £4 p.a.

On leaving school, probably in his early to mid teens, it is believed Dargan spent some time working on his father’s land and that his first job was in the Carlow county surveyor’s office.14There were reports of a career setback, possibly an unsuccessful application for a job with the Carlow Grand Jury, the body responsible for a wide range of public works in the county.15At this point two influential patrons, John Alexander and Sir Henry Parnell MP, enter Dargan’s life, possibly through the efforts of Lord Portarlington, the family’s landlord.

John Alexander ran his successful mills at Milford, Co. Carlow, once very extensive according to the 1840 travel diaries of Mr and Mrs Hall.16The ruined building still stands in a picturesque location on the River Barrow from which it drew its power. Somehow Alexander came to hear of the young Dargan and seeing his talents decided to help the young man at the start of his career.

The Milford mills complex owned by John Alexander’s family was once one of the largest in Ireland. This derelict building is one of the few survivals of this vast enterprise.

Milford, the small station south of Carlow town, closed in 1963.

Telford’s Great Road from London to Dublin

It is easier to establish the nature of the support William Dargan received from Sir Henry Parnell, MP for Queen’s County (Laois), a major political figure at the time and an uncle of Charles Stewart Parnell. Parnell the elder spotted the talents of the young Dargan around 1819 and found a job for him on Telford’s great road. It is quite possible that Alexander referred Dargan to Parnell, knowing of his involvement in public roads.

As a government minister Parnell travelled often to London via Holyhead, ‘the barbarous little hamlet’ as F.R. Conder described it, enduring the hazards of the mountainous track taken by the mail coaches across north Wales into the English midlands and on to London. Samuel Smiles described the road across Anglesey as a dangerous, ‘miserable track, circuitous and craggy, full of terrible jolts, round bogs and over rocks’.17After braving another watery crossing of the Menai Strait the weary traveller faced the road across north Wales, which was ‘rough, narrow, steep and unprotected, mostly unfenced and in winter almost impassable’. One coach in 1815 took forty-one hours to cover the 225 miles (363 km) from Holyhead to London.

This building at Holyhead was once the Eagle and Child Inn. In the early 1800s surveyors and engineers measuring sections of the Holyhead road used it as a common reference point in their journals.

This was the principal line of communication between the government in London and Her Majesty’s Irish subjects. The problem was that maintenance of the Holyhead Road was the job of several turnpike trusts who levied tolls to cover the cost of road repairs. These trusts were notoriously corrupt and proceedings were speedy and secretive, with much jobbery, partial allocation and outright fraud, so that only a small part of the funds allocated trickled down to road repairs; hence their poor state.18

In 1814 Parnell wrote to Robert Peel complaining bitterly about the state of the road and the discomfort and dangers of the journey to London he and the other 13,000 travellers annually had to endure. The government appointed Parnell chairman of a parliamentary commission whose task was to prepare estimates and supervise construction of what was essentially a new road. The Commission entrusted the project to the great Scots engineer, Thomas Telford,19and the two men worked closely on it, becoming friends. Parnell was a frequent guest at Telford’s engineering dinners held in his Westminster house.

Who You Know

There are several layers of connection here, all suggesting the contacts and support which helped Dargan in his early career and later when his business was thriving.

The Halls, who were friends of John Alexander of Milford, later became friends of William and his wife-to-be, Jane Arkinstall. Thomas Fairbairn of Manchester (who built the 120 hp mill engine at Milford) was later a close friend and business associate of Dargan’s and supplied many locomotives to him and the railway companies for whom he worked.

John Alexander became in time a director of the Irish South-Eastern Railway, which Dargan built through Carlow towards Kilkenny. Alexander was a relation of the Earl of Caledon (whose family name is also Alexander). Dargan had close links with Lord Caledon while building the Ulster Canal in the early 1830s.

Sir Henry Parnell, Charles Stewart Parnell’s uncle, became Minister for War and later Paymaster-General in Lord Melbourne’s government, becoming Lord Congleton in 1841. In later years, like other members of the Parnell family, he began to suffer bouts of insanity. These became increasingly serious and some time later hanged himself. ‘That fatal strain again’, as F.S.L. Lyons puts it.

We have an 1836 account directly from Dargan himself of his duties on the Holyhead Road from evidence he gave while enduring spirited parliamentary cross-examination about a bill to authorize the Dublin & Drogheda Railway.20He said he was an inspector of works and resident engineer under Telford rather than simply an overseer, as had been suggested by learned counsel, and was a works manager under one of three principal supervisors, William Provis. It was Provis’ job to submit daily works journals to London for each section of the road under construction, information supplied by a number of inspectors, including Dargan.

These handwritten journals are still in existence and contain detailed information about the number of men and horses on site every day, the hours worked, the weather, tasks completed, overall progress and any unusual events.21More specifically Provis also described the job of a works manager like Dargan as logging time and materials used, deploying workmen, removing rubbish, checking bridges, drains and fences, keeping a daily journal and paying the men’s wages. A works manager earned 24 shillings a week in the first year, rising to 27 shillings in the second year and 30 shillings thereafter. Provis and Dargan worked together on canals in the English midlands some years later and Dargan must have been fond of him because he kept a bust of his old boss in his Mount Anville house. An assistant of Telford’s on the Holyhead Road was John Macneill, later to become a leading engineer in his day and first Professor of Engineering at Trinity College. Macneill earned 2½ guineas per day in Wales (£2 10s6d), a substantial salary when the average wage for an unskilled labourer was just 1s6da day. He and Dargan worked on many projects together but their relationship was more professional than amicable.

Sir John Benjamin Macneill (1793–1880)

John Macneill, a leading nineteenth-century Irish civil engineer, was born at Mount Pleasant House, Dundalk, a fine house with ‘something of the air of one of the smaller government houses of the British Raj’, as Bence Jones describes it. (The building, called Mount Oliver, is now a religious institution.) After five years in the Louth militia, Macneill, like Dargan, worked with Thomas Telford on the Holyhead Road from 1826–33. The Drummond Commission appointed him to plan railway developments in the north of Ireland and his colleague Charles Vignoles did the same in the south. Macneill became the first Professor of Civil Engineering at Trinity College in 1842 but his interest lay more in building railways than teaching others how to build them.

He was involved in almost every major railway project in Ireland, working closely with Dargan on many of them, sometimes with sparks flying. They were not exactly friends, more like close colleagues. Like W.R. Le Fanu and other prominent engineers, Macneill was a freemason. He was also quite litigious: in 1849 he sued Durham Dunlop, the editor of the influentialIrish Railway Gazette, for libel, not a wise move and one he was to regret. In later life Macneill went blind and lived in relative poverty in London. However, the story that he was reduced to selling matches on the city’s streets is a myth. He died in a house on the Cromwell Road and is buried in Brompton Cemetery. Long unmarked, the Institution of Engineers of Ireland and Trinity College Dublin erected a plaque over his grave in 2001.22

Apart from often having to make the journey to London, Parnell had a particular interest in road construction and wrote a book on the subject. He gave detailed technical instructions to the works inspectors on the Holyhead Road such as Dargan who were to supervise a foreman and a gang of labourers ‘quarrying rock, gathering field stones, getting gravel, breaking stones, scraping the road, loading materials into carts and all works that are reducible to measure’.23Parnell opposed pitting contractors against one another since they would cut corners if the price was too low, leading to disputes, ruinous subcontracts and law suits.24Telford’s instructions were equally clear. He insisted the surface had to be elliptical for drainage with a solid pavement of large stones laid close together, a binding of walnut-sized stones and a layer of gravel. He favoured employing women and boys to break the smaller stones and advised payment by piece-rate.

The Stanley Sands toll-keeper’s house by Thomas Telford on Holy Island near Anglesey whose design resembles a traditional Welsh hat and provided a view of travellers coming in both directions. Dargan adapted a similar one-storey design for his lock-keeper’s cottages on the Ulster Canal.

The last section across Anglesey passes over the Stanley Sands to Holy Island and is closely identified with Dargan. Telford decided on a completely straight road from the Menai Strait to the Eagle and Child Inn, Holyhead at a cost of £52,221 12s7dover four years.25In autumn 1821 work began on lot 8, the Stanley Sands embankment, which was 1100 yards long, 34 ft wide, 16 ft above the sands with a bridge on a rock outcrop for tidal flows.26By February 1822 most of the road across the island was complete and the embankment well in hand.27Provis reported the embankment was complete in summer 1823 and had opened with an elegant toll house and gates at the western end.28The Stanley Sands was Dargan’s first major engineering project, a most useful training for his later work on the Howth road, the coastal route of the Dublin & Kingstown Railway and the Foyle and Wexfordslobland reclamations. Ten years later, when tendering for the Dublin & KingstownRailway, Dargan travelled with the company’s engineer, Charles Vignoles, to view this work on the Stanley Sands in April 1832 (see Chapter 2).29

For Those in Peril: 1843

Although the completed road was a vast improvement Thackeray wrote an account of one disagreeable journey through Wales in his 1843Irish Sketch Book:

The coach that brings the passenger by wood and mountain, by brawling waterfall and gloomy plain, by the lonely lake of Festiniog, and across the swinging world’s wonder of a Menai bridge, through dismal Anglesea to dismal Holyhead – theBirmingham Mail– manages matters so cleverly, that after ten hours’ ride the traveller is thrust incontinently on board the packet, and the steward says there’s no use providing dinner on board because the passage is so short.

Both Telford and Parnell were pleased with Dargan’s input and happy to recommend the rising young engineer for other projects. He was now ready to return to Ireland and put that knowledge to good use in the next phase of his career.

The Colossus of Roads: Thomas Telford (1757–1834)

Born in poverty in Dumfriesshire, the son of a shepherd, this great engineer became an apprentice stonemason at fourteen before moving to London. As Shropshire county surveyor he built forty bridges and then worked on roads, harbours and canals, including the magnificent stone and iron viaduct carrying the Llangollen canal high over the River Dee valley.

Telford’s greatest project was the London-Holyhead road, now the A5. Beyond Shrewsbury it was virtually a new road. The 1826 Menai suspension bridge was a triumph and his journals describe the heart-stopping tension as early one morning he watched the first raising of the vast iron link cables holding the bridge.

The poet Robert Southey assigned Telford the ‘colossus’ title; another was the ‘Pontifex Maximus’. John Macneill worked closely with Telford on the Holyhead Road, as did Dargan in the later stages. Telford always wrote of Dargan in very warm terms. He was a poet in his own right and wrote his autobiography but never married and had no known family. He held regular all-male engineering dinners at his house, 24 Abingdon Street, beside the Houses of Parliament. He died there in 1834 of a ‘bilious derangement’, as his clerk described it.

With the highway open to Holyhead and the journey time by coach from London cut from forty hours to a more manageable twenty-eight, the final stage of the London-Dublin mail coach route was the road from Howth to Dublin. Although a difficult harbour to use, Howth was the main packet station until cross-channel ships transferred to Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire). Impressions of Howth at the time were almost as negative as those of Holyhead. An anonymous writer advised anyone travelling to this ‘village of wretched thatched cabins’ to bring ‘a troop of horse to guard against robbers and a gunboat for protection against sea pirates’.30

In 1823 Telford ordered a detailed survey of the road from William Duncan (most likely Dargan), which found it was in a poor state and subject to frequent flooding from the sea but not as bad as the Holyhead road before completion.31Dargan rebuilt the entire road with a solid stone sea wall from Clontarf crescent to Sutton. It drew high praise from Telford and Parnell, who described it as ‘in a perfect state … a model for other roads in the vicinity of Dublin’.32Dargan’s work is still visible in the low sea wall, which resembles the one he built across the Stanley Sands near Holyhead. Even better, Col. John Burgoyne of the Commissioners of Public Works, a man who would feature in Dargan’s career when he began to build railways, persuaded the Treasury to award Dargan a premium of £300 for the quality of his work.33This was a large sum of money and apart from the confidence it expressed, gave Dargan the vital seed capital needed to set up his business in Ireland.

3. Dargan’s First Contracts

With the Holyhead and Howth roads now complete, Dargan was beginning to make a name for himself as one of Telford’s rising stars. As well as building roads Parnell had become interested in improving the Barrow Navigation, canals being one of the chief means of transporting goods and passengers in the pre-railway era. In 1824 the Barrow company offered Dargan the post of superintendent and he presented his resignation to Telford who replied warmly from Edinburgh that he was sorry to lose him and that his conduct was always ‘perfectly satisfactory’.1Both Telford and Parnell advised him to take the job, which he did, but it is not known how long Dargan held it.

Dargan then began to work for a number of turnpikes. In late 1827 the Malahide Turnpike noted it had received ‘a letter from a person of the name of William Dargan’ in response to a press advertisement. Dargan said he would maintain the Malahide and Summerhill roads for five years, protect the footpath from Summerhill to Ballybough, provide a ‘good, firm, even surface’, fix the road from Fairview Crescent to Malahide with a footpath, all for £2000 with £500 for repairs and £900 for other improvements.2Not being prone to hasty decisions the trustees were still discussing his tender five months later and finally decided to award a basic maintenance contract worth just £30 to Thomas Carney.

Dargan was more successful in his native Carlow, becoming a surveyor on the Dublin-Carlow road. He calculated the job would take ten months and his estimate for the Castledermot to Carlow section is included with the plans deposited before parliament bearing his signature.3

At the 7 July 1829 trustees’ meeting at Ball’s Inn, Blessington, Dargan offered to act as clerk without an increase in his surveyor’s salary of £100 p.a.4At the next meeting, 12 August 1829, the trustees ordered him to spend £134 on repairs at Tallaght, Dolphin’s Barn and Poulaphouca. From then until 6 July 1830 the minutes are in his handwriting and signed by him.5Later he was ordered to erect milestones with corrected figures and sat on a committee to decide work priorities.6Dargan also invested in the turnpike: the next month he took a number of £100 debentures, to be partly repaid in road tolls and in July 1830 estimated repairs to one section at £150 13s4d.7At this meeting Capt. Derenzy became overseer and replaced Dargan as clerk. The meeting also defined Dargan’s duties as surveyor: to inspect the whole road once a month, account for expenditure and provide a quarterly estimate of projected work, the number of men needed and their wages. In 1831 he agreed to seek a government loan and provided a three-month estimate for a section near Carlow:

By autumn 1831 Dargan was beginning to reduce his involvement with the Carlow turnpike as he focused more on the Kingstown railway.8However, Dargan had a repair contract for the Circular Road, Dublin, running 5 miles 80 perches from Leeson Street and Kilmainham to Summer Hill, beginning on 1 December 1829, worth £28 11s5dp.a. per mile with £150 annually for upkeep.9He attended thirteen board meetings over the three years and the secretary reported the materials he used were excellent.

The Dunleer turnpike contract, covering a section of the Dublin-Belfast coach road, was more controversial. The commissioners approved his plan to reroute one stretch near Balrothery to save costs after which Dargan won a year’s contract for the Dublin-Swords road from 24 December 1828, worth £650, paid quarterly.10He received £81 in February and £189 16sin June 1829 but from then on relations deteriorated. In reply to a remonstrance about delayed repairs from William Robinson, Turnpike Secretary, Dargan wrote: ‘The most satisfactory reply I could give you would be by getting to work quickly’.11

Robinson then said the Swords road was ‘exceedingly bad’ and needed Dargan’s ‘prompt exertions to put it in to passable repair, which I hope you will immediately attend to’.12A fortnight later Robinson was more insistent: the Dunleer road was in ‘very bad condition’ part of it being ‘completely worn down’ and if Dargan did not fix it his ‘sallary will be withheld on next quarter’s day’.13Soon after he added that sections at Drumcondra, the fifth milestone, Pennock Hill, Swords and the tenth milestone needed ‘immediate and substantial repairs’ while the Swords footpath was ‘in a ruinous state which I am sorry to say you have intirely neglected’.14Despite these complaints Dargan received £225 in May 1831, made improvements at Cloghran hill (for which he earned £65 6s6dplus £100 for his main contract) and was asked to submit plans for Julianstown bridge and hill.15

Illness prevented him attending the meeting on 1 August 1831 but he wrote: ‘As I am very much in want of money, you will greatly oblige me by having the amount of my quarter’s contract forwarded to me by Mr Robinson.’ This produced £250 a few days later.16Dargan missed the next meeting for more dramatic reasons: ‘Some riots having occurred in Banbridge [cut] on the works carrying on there by me. I am obliged to be present this evening at the Investigation.’ He concluded the works were now, hopefully, satisfactory and added: ‘I want money very much.’17But a month later Robinson complained about the ‘very bad order’ of the Swords road, which was ‘in a wretched condition for want of gravel’, with similar problems at Balrothery, north of Gormanstown and north of Drogheda.18He said he would hire men if Dargan failed to remove piles of materials near Santry and clear the blocked water table at Swords. Not surprisingly matters came to a head and Dargan tendered his resignation on 21 November 1831. The Commissioners had expected his contract to run for three years from February 1830 and began proceedings against him estimating the urgent repairs would cost £400.19A year later, because there was ‘no injury or loss sustained by the public’ from his resignation, the Commissioners instructed their lawyer to drop the legal action.

This contract may have been troublesome because Dargan underestimated the work or he may have been distracted by his Banbridge and Kingstown railway contracts. Four years afterwards, he argued before a Lords Committee that he was free to end the contract at any time and when the Dunleer Trustees criticized his work unfairly and retained part of his fee, he did so. His response to them was: ‘Now, gentlemen, I have kept the road in good order as far as I bargained, and now you have paid me, our engagement ceases.’20At the same parliamentary committee Mr Joy, counsel, argued that many of Dargan’s contracts, the Kingstown Railway, Ulster Canal, Dunleer road and Kilbeggan Canal were blighted by disputes and poor relations. Dargan countered that they were complex, demanding a flexible response from him to problems that were impossible to foresee, that costs overran and apart from the Kilbeggan Canal, he had concluded all these contracts amicably.

Canals in the English Midlands

One of Telford’s last engineering projects before his death in 1834 was the construction of the appx. 40-mile (64 km) Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal. This was a slight misnomer as the canal was nowhere near either city but built to connect existing waterways. The canal cost over £800,000 in total and Provis and John Wilson won the substantial contract to build the 39 miles of the main line.21Dargan was by now quite well off as indicated by the fact that in 1826 he took twenty £100 shares in the company.22He described his duties a few years later to a parliamentary committee thus: ‘I surveyed the principal portion of the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction Canal. I was then assistant manager for Mr Prowes [Provis] on these works and I contracted afterwards for some works on the Middlewich canal … [I was] three years surveyor, superintendent and contractor.’23

The deep cutting of the Birmingham & Liverpool Junction canal at Woodseaves has an unusual keyhole opening to reduce the dead weight of the filling on the whole structure. The Spectacle bridge between Ennistymon and Lisdoonvarna is similar to it.

A high bridge of mixed materials carries the road over the B&LJ Canal near Gnosall.

The second contract, with Dargan as assistant manager, proved difficult. At Woodseaves a mile-long cutting, 90-ft deep, a mile-long 50-ft embankment between Knighton and Sheldon and a 2-mile cutting at High Offley were very troublesome.24Worst of all was a mile deviation through Norbury Park, made at Lord Anson’s behest: there were almost endless collapses until several years later a solid bank was built.25Vignoles admired the ‘great canal excavations of Mr Telford’ when he saw them in 1833.26Telford left his sick bed in London to inspect the works but died on 2 September 1834, six months before the opening and the first boat passed through the completed canal on 2 March 1835. Eleven years later Robert Scott MP described it as ‘one of the best canals in the kingdom … constructed on the best principles of canal-making’.27

Walking Dargan’s Canal

In April 2011 I walked a delightful five-km stretch of the Birmingham&Liverpool Canal around Gnosall, Shebdon, Woodseaves and High Offley in Staffordshire This is now part of the Shropshire Union Canal, a popular and busy leisure waterway. Near Gnosall (pronounced ‘Knows-all’), there is a long deep cutting and a tunnel through the sandstone with crudely finished walls and roof, unlike many of the pretty little road bridges, which have lovely curves of beautifully cut stone. The lack of finish suggests the company was under financial strain and had to economize. Another very deep cutting near Woodseaves has a high bridge with a curious keyhole.

Dargan also won part of the contract to build the 9¾-mile Middlewich Canal, a feeder branch of the B&LJC towards Manchester, which cost £129,000 and opened on 1 September 1833, eighteen months before the main canal.28It is uncertain how much of the contract work Dargan completed and his testimony suggests he worked on the main line before the branch.

Dargan’s Wife

Dargan came back from the English midlands with more that just useful experience – he also acquired a wife. On 13 October 1828 he married Jane Arkinstall in the Anglican parish church of St Michael and All Angels, Adbaston, Staffordshire, which is close to the route of theB&LJCanal. The curate who celebrated the wedding was Charles Thomas Dawes and the witnesses Sarah Arkinstall and William Arkinstall. Jane was born in Adbaston, the daughter of Thomas Arkinstall and Jane Elizabeth Armson.29It is tempting to read doctrinal significance into the fact that Dargan registered his home parish as St Thomas’ Church of Ireland parish, Marlborough Street, Dublin and that he was married in an Anglican church.30It was the norm in those days for a wedding to take place in the bride’s home parish and perhaps like many a young man he was not that concerned about religious faith.

We can presume that William met his future wife while working on Telford’s canals. There is no mention of members of William’s family being present nor of a honeymoon. The couple did not have any children.

Looking North

Returning to Dublin with his new wife, Dargan decided to focus his business efforts on Ireland, looking around for more substantial projects than simply fixing roads or building canal sections. The north-east of the country was then more developed than the rest of Ireland so it made sense for him to concentrate his energies there. He won a contract for major improvements to the centre of Banbridge, Co. Down, the first of several projects he undertook in the north. Between 1831 and 1833 Dargan built a new market house in the town (still standing), dug a deep excavation to lower the steep main street (590 ft long and 16 ft wide/180 x 5 metres) and built a granite arch across it with a carriage road on either side, at a cost of £19,000 plus £2000 for the market house.31These works completely changed the appearance of the town.

The pretty little Anglican church of St Michael and All Angels, Adbaston, Staffordshire where William Dargan married Jane Arkinstall on 13 October 1828.

The entry in the registry for the marriage of Dargan and Jane Arkinstall. Courtesy Staffordshire Records Office.

Dargan dealt with a local man on this project, William Reilly DL, advising him that it would give Banbridge a ‘novel and interesting appearance’.32Others were not so enthusiastic: writing in theOS Memories of Ireland, Lt George Bennett RE said when he saw the cut in 1834 he thought while it was ‘of great benefit to travellers, [it] is none to the inhabitants, indeed, on the contrary, and it is the subject of much complaint’.33More recently the market house was described as ‘a foursquare-plus building of random blackstone with heavy granite quoins at the corners and to the central projection’.34