9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

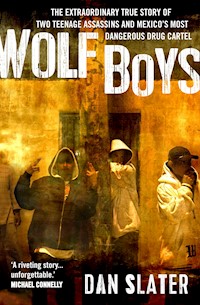

A chilling true story of two American teens recruited as killers for a Mexican cartel, and their pursuit by an increasingly disillusioned detective. At first glance, Gabriel Cardona is an exemplary American teenager: athletic, bright, handsome and charismatic. But his Texas town is poor and dangerous, and it isn't long before Gabriel abandons his promising future for the allure of the Zetas, a drug cartel with roots in the Mexican military. Meanwhile, Mexican-born Detective Robert Garcia has worked hard all his life and is now struggling to raise his family in America. As violence spills over the border, Detective Garcia's pursuit of the Zetas puts him face to face with the urgent consequences of a war he sees as unwinnable. In Wolf Boys, Dan Slater takes readers on a harrowing, moving, and often brutal journey into the heart of the Mexican drug trade - from the Sierra Madre mountaintops to the smuggling ports of Veracruz, from cartel training camps and holiday parties to the dusty alleys of South Texas. Ultimately though, Wolf Boys is the intimate and vivid story of the 'lobos': teens turned into pawns for cartels. A non-fiction thriller, it reads with the emotional clarity of a great novel, yet offers its revelations through extraordinary reporting.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Allen & Unwin

First published in the United States by Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Copyright © Dan Slater, 2016

The moral right of Dan Slater to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Fax:020 7430 0916

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 76029 147 1

E-book ISBN 978 1 95253 488 1

Internal design by Lewelin Polanco

CONTENTS

Prologue

PART I – The Straight Hard Workers

1 – You’re Not from Here

2 – Flickering Candle

3 – My Dad Does Drugs

4 – The Noble Fight

5 – Overachieving Bitch

6 – Underworld University

PART II – The Company

7 – Original Vice Lord

8 – Bank of America

9 – The New People

10 – Raising Wolves

11 – I’m the True One

PART III – Spillover

12 – In the Dirty Room

13 – Garcia’s Orgasm

14 – Corporate Raiders

15 – The Clean Soul of Gabriel Cardona

16 – The Kingdom of Judgment

17 – Who’s the Next Top Drug Lord?

18 – All in the Gang

19 – Brothers of the Black Hand

20 – Lesser Lords

21 – A Boner for Bart

22 – The Varieties of Power

23 – I’m a Good Soldier!

PART IV – Prophecy

24 – Last Meal

25 – Heroes and Liars

26 – Career Moments

27 – Catch That Pussy

28 – Twilight

PART V – Frozen in Time

29 – Legend of Laredo

30 – The Messiest War

31 – No Angels

32 – Hypocritical Bastards

33 – Another Media Guy

Epilogue

A Note on Sources

PROLOGUE

As dusk settled over South Texas, Gabriel Cardona stood in the kitchen of the safe house and offered a last-minute tutorial. “You walk up to him and just poom!” he told his newest recruit. “En la cabezota. But with both hands. In the crown, poom! You’ll fuck him up. Otherwise, poom! poom! poom! poom! Four in the chest. And then en la cabezota, to make sure.”

The recruit nodded, and scattered to his preparations.

Four days had passed without a successful action. Other than one bungled job, in which they nearly killed the wrong guy, they’d been hanging out in the rented house, a charming brick rambler on Orange Blossom Loop, eating fast food, mowing the lawn, shopping for housewares at Wal-Mart, and talking to girls on their wiretapped cell phones. They were young and vigorous, fiery in their belief of success. Now they were getting ready to kill again.

“It’s time to take care of business!” Gabriel yelled, clapping encouragement like a high school football coach on Friday night. He’d come quite a way from the ramshackle house across town on Lincoln Street—three blocks north of the international border between Mexico and Laredo, Texas—where his mother raised him and his three brothers on less than $20,000 a year. Gone were the days of borrowing mom’s Escort, of dressing in jeans and generic white T-shirts. His closet was now stuffed with brand names like Hugo Boss, Ralph Lauren, Versace, and Kenneth Cole. He still cut his hair at Nydia’s Salon. That would never change. But now he drove new cars—a Jetta, a Ram, a Mercedes SUV. His silver Benz was being customized; it would be ready any day.

He paced the kitchen, threw away a greasy fast-food bag, and washed the dishes left in the sink.

Success, the young man was finding, came with its own stress: the hangers-on, the wannabes, the phony homies, the unwanted attention from a certain detective. The competition. Richard, his new lieutenant, was growing more subversive by the day. Uncle Raul, his mother’s brother, a perennial troublemaker, kept hitting the clubs across the border and mouthing off, relying on his nephew’s reputation to keep him out of trouble. Uncle Raul would not last long if he kept that up. And then there was Christina, she of the pretty face and the not-too-wide hips, who felt abandoned while her boy worked constantly, always on the run.

It was six months from his twentieth birthday, and Gabriel Cardona was being primed for a managerial position in a global enterprise. A bilingual businessman, savvy in two cultures, he could work both sides of the border with ease. A born leader, handsome and serious, he had caramel skin, full lips, and the dark, brooding eyes of a sad Catholic saint—the type that lined the walls of his mother’s home in fading lithographs. The deity, fellow decider of fates, had cut him strong and wiry. Angel of the Lord, lord of the hood. A thug. The chuco that even preppy girls competed over.

He’d made some mistakes. But any man of action did. He’d proven himself a firme vato, a loyal soldier with balls of steel. In the shit-nothing town of Laredo, Texas, where Company membership was the pinnacle of achievement, this status meant everything. His boss, Comandante Cuarenta—or simply “Forty”—precisely the most feared drug lord in Mexico, liked him. Liked him so much that he wanted to protect him. Recently, Forty instructed Gabriel to exclude himself from jobs, to hang back and direct via cell phone but not participate unless necessary. Liked him so much, in fact, that Gabriel had been bailed out of jail, not once, but three times in the last eight months, at a cost of several hundred thousand dollars.

The law kept letting him out. The Company kept paying for it. What clearer validation could there be?

A year earlier, when Forty began sending him on jobs in Texas—as in the States—Gabriel was reluctant, caught between the future-less fringe of his birth country and the narco-state where success accrued to the ruthless warrior. Doing missions in a place where authorities frowned on homicide was not an appealing prospect. But it was Forty asking. That a boy from Lazteca received orders directly from El Comandante, even for suicide missions, was immense.

Gabriel had long imagined a moment such as this, one of great responsibility, an opportunity to advance in a way his community admired. For months he’d been breakfasting on “roches,” a heavy tranquilizer, and Red Bull. And risk, well, it was the toll of immortality. Look no further than Forty himself. Stoic. Serious. Never asked you to do something he wouldn’t. Loyal to friends. Enemy to enemies. A good man, for and about the idea. Gabriel was part of something, and a true Wolf Boy never said no.

That evening, the cars had been cleaned, the weapons loaded. Everything was ready. This was it. The beginning of something. He could see a future. As the battle with the Sinaloans, the rival cartel, drove up costs and pinched smuggling profits, the border’s underworld economy cycled down. The transport business would come and go. But enforcement was steady work. He would stack money. He would be transferred to deep Mexico, where he would run his own city. If he could cook his nemesis, La Barbie, a Sinaloan, then third-in-command was not out of the question. The other boys looked up to him. Richard would fall in line. Christina would calm down. She was mad. But earlier that evening they had returned from Applebee’s, where they had had a constructive conversation. When he dropped her off, she told him to hug her. “Tighter,” she said.

He moved about now with quicker steps, rolling a fist in a palm, rubbing the scars beneath his buzzed hair where shotgun fragments remained from old battles. If Gabriel could cement his reputation as a leader, if the past year could ever make sense, it would have to come now, at the battle’s most crucial point, under a flood of spotlights, before hundreds of men who would either anoint him the next mero mero, the true shit, or throw him to the hungry tigers like one more disposable spic.

Forty said 2006 was the last year of war. Forty said Mexico’s next president was on lock, paid for, and the country would be theirs. Todo va a ser de La Compañía. Everything will belong to the Company.

But there was a commotion outside the house, then a slamming. A stun grenade came through the front door. The concussive blast disturbed the fluid in Gabriel’s ears. He wobbled. A bright flash bleached the photoreceptors in his eyes, blinding him for three seconds. One. Two. Three.

He was facedown on the carpet, hands cuffed behind him. He thought he might die. He thought he might escape.

The world of possibility was vast.

PART I

The Straight Hard Workers

Praise belonged to those most daring in the quest for rare and exotic things, for their physical and mental toughness, their stamina, their fighting prowess in face of sudden ambush, their audacity in the face of the unknown.

—AZTECS,INGACLENDINNEN

1

You’re Not from Here

Robert Garcia was twenty-nine the first time he questioned success. Every accomplishment, it seemed, came with some deficit or drawback or innocence-eroding knowledge. You earned a scholarship but didn’t feel college. You won the battle but lost the bonus. You fell in love, and faced a dishonorable discharge. The autumn of 1997 should’ve been the brightest season in Robert’s promising career, but it arrived with sorrow. The yin and the yang, he called it.

Two decades earlier, as a child of Norma and Robert Sr., Robert emigrated from Piedras Negras, Mexico, to the Texas border town of Eagle Pass—an international journey of one mile. Robert Sr., needing to support his family, had been working in the States as an illegal immigrant; once he demonstrated an income and showed that he was spending money in Texas, he gained a green card for the family, meaning that Norma, Robert Sr., Robert, and Robert’s younger sister, Blanca, could come to the States as “resident aliens,” not U.S. citizens. After they arrived, Norma gave birth to another daughter, Diana, and another son, Jesse.

Robert, the oldest, started third grade in an American school. After school and on weekends, he and Robert Sr. picked cucumbers, onions, and cantaloupes on local farms. In spring and summer, Norma, a seamstress for Dickie’s, the work-wear manufacturer, stayed in Eagle Pass with the girls and Jesse while Robert and his father followed fellow migrants to Oregon and Montana for the sugar beet season. There, Robert attended migrant programs at local schools. Dark-skinned but ethnically ambiguous, he found northern communities mostly welcoming, with their food festivals and roadside stands where Indians sold tourist stuff. The verdant landscapes were a reprieve from the dusty flatiron of South Texas. America was a beautiful place.

Back in Eagle Pass, land was cheap. There were no codes. People could build what they wanted. The Garcia family lived in a two-room hut while they built the home they’d live in forever. It was piecework. They saved up, then tiled the bathroom; saved more, then bought a tub. In winter they heated the place with brazas, coal fires in barrels, and in the mornings Robert went to school smelling like smoke.

When would the house be finished? No one asked. Work drew them together.

As other immigrants settled nearby, Robert Sr. built a one-man concession stand where he sold snacks and sodas to neighborhood kids. Robert Sr. brought his family to the States for a better way of life, but in his mind he would always be Mexican. He was proud to live next to other immigrants in Eagle Pass. By the time Reagan took office, their patch of dirt was becoming a bona fide suburb, sprouting neat rows of handmade houses. When neighbors needed assistance with an addition or a plumbing issue, they turned to “the Roberts” for help.

Robert Sr. treated his oldest boy like a man, and Robert’s siblings respected him as a kind of second father. Trim, bony, and bespectacled, he walked taller than his five feet, eight inches. In high school, he enrolled in ROTC and played bass clarinet in the marching band. He finished high school a semester early, took a fast-food job at Long John Silver’s, and deliberated over whether he should capitalize on a college scholarship in design, or go in a different direction.

At seventeen he seemed to know himself: hyperactive, confident. He had a talent for improvisation. He was respectful in a rank-conscious way, but didn’t care what others said or advised. Introverted and impatient, he had his own way of doing things. He learned as much from his father as he did in school. He also felt the lure of service, a patriotic duty toward the adopted country that gave him and his family so much. Formal education, he decided, was not for him. So, in the summer of 1986—the same year a boy who would change Robert’s life was born in Laredo, another Texas border town 140 miles southeast—Robert, much to the dismay of his non-English-speaking parents, passed up the scholarship and enlisted in the U.S. Army.

Since he’d enrolled in ROTC during high school, he arrived at basic training as a seventeen-year-old platoon leader, instructing men who were older. To compensate for the age difference, and his small size, he acted extra tough and earned the nickname Little Hitler. After basic training, he began to work as a watercraft engineer at Fort Eustis, Virginia, where he picked up a mentor, a sergeant major, who led him to work on military bases in Spain and England. On the bases, he played baseball and lifted weights. Little Hitler sported ropy arms. His neck, once nerd-thin, disappeared into his shoulders.

In the Azores islands, on a small U.S. Navy installation off the coast of Portugal, Robert met Veronica, a blond gringa from Arizona. The daughter of a navy man, Ronnie was the only female mechanic at the base. She was tough. While fixing the hydraulic system on a tugboat one day, Robert snuck up and slapped her neck with grease-shaft oil. She wheeled around, called him an asshole. “Fuck off!” she said. One week later they conceived a son.

Ronnie was twenty, already married to a soldier, and had a two-year-old son. Her parents never liked her husband. As far as they were concerned, he was a freeloader who drank excessively at the bar they owned in Arizona. They didn’t like seeing their daughter be the breadwinner and the parent. And now here was Robert: didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, would do anything for her.

But adultery in the military was a serious crime; at the discretion of a military court, it carried felony time and a dishonorable discharge. The chiefs read Ronnie and Robert their rights. They owned up to the affair. Ronnie’s husband flew to Portugal; furious, he stomped around the base, drank, got in fights, and broke windows at Ronnie’s house. No one liked her husband. So the chiefs held a meeting to arbitrate the love triangle, and let Robert and Ronnie walk away with reprimands. When the husband called Ronnie’s mother and said, “Your daughter’s a whore!” Ronnie’s father grabbed the phone and said: “You weren’t even born from a woman! Two freight trains bumped together and you fell out of a hobo’s ass!” From there, the separation went smoothly.

In 1991, Robert’s four-year military contract neared its end as the First Gulf War started. Robert saw other soldiers reenlisting and collecting $10,000 bonuses. He was willing to reenlist, until the U.S. government offered him citizenship instead of the bonus. Robert didn’t care much about citizenship. Like his father, he’d always think of himself as Mexican; and, besides, his resident-alien status entitled him to a U.S. passport. But he still took the denial of the bonus—and the offer of citizenship as a substitute for the money that other soldiers received—as an insult. How could he serve his country for four years and not get citizenship automatically? So he declined reenlistment, walked away with neither the bonus nor citizenship, and returned to Texas with Ronnie and the boys, where he got a job as a diesel mechanic in Laredo—a border town neither of them knew.

IF IT WAS YOUR FIRST time, you drove south on Interstate 35, passed San Antonio, and expected to hit the border, but the highway kept plunging south. Texas hill country flattened out into a plain so fathomlessly vast, it gave you a feeling of driving down into the end of the earth. One hundred twenty miles later, and still in America, you reached the spindly neon signs of hotels and fast-food joints, gazed back north, and felt as if what you’d just traveled through was a buffer, neither here nor there. To the west, several blocks off I-35, rows of warehouses colonized the area around the railroad track. To the east, upper-middle-class suburbs gave way to sprawling developments, ghettos, and sub-ghettos called colonias. Go two more miles south, and I-35 dumped out at the border crossing, 1,600 miles south of the interstate’s northern terminus in Duluth, Minnesota.

Robert and Ronnie were small-town people. Sprawling Laredo, with its 125,000 residents, was a big city compared to a place like Eagle Pass, which had a population of fewer than 20,000.

“Oh well,” Ronnie sighed. “We’ll try it for a year or two.”

A few months later, while recovering from a work-related hand injury, Robert saw an ad for the Laredo Police Department. He enjoyed public service more than working for a company. But he had to be a U.S. citizen to be a cop. He didn’t see any benefit to citizenship, aside from this policing career, and wasn’t feeling especially patriotic after his snub by the military. He wondered: What would his father do? His father would shut up and do right by his family. Land the career, move forward. So Robert studied, took the test, and took the oath of U.S. citizenship.

When he joined the force, the Laredo Police Department employed about two hundred officers. Cops purchased their own guns. Uniforms consisted of jeans and denim shirts, to which wives sewed PD patches. Each patrol covered an enormous area. Squad cars called for backup, and good luck with that. But aside from domestic spats and some armed robbery, the city saw little violence. Across the river, Nuevo Laredo, with its larger population of 200,000 people, wasn’t much worse. Drug and immigrant smuggling were rampant. But a smuggler’s power came less from controlling territory with violence and intimidation than from the scope of his contacts in law enforcement and politics, and his ability to operate across Mexico with government protection. In exchange for bribes, politicians and cops refereed trafficking and settled disputes.

Mexico’s narcotics industry was well organized. The business consisted of two classes: producers and smugglers. On the western side of Mexico, in the fertile highlands of the Sierra Madre Occidental, gomeros—drug farmers—contracted with smuggling groups to move shipments north to border towns. In the states of Sinaloa, Durango, and Chihuahua, an ideal combination of altitude, rainfall, and soil acidity yielded bumper crops of Papaver somniferum. Those poppy fields—some with origins in plantings made by Chinese immigrants a century earlier—produced millions of metric tons of bulk opium per year. Marijuana, known by its slang, mota, was Mexico’s other homegrown narcotic. When the marijuana craze hit the United States in the 1960s, mota came chiefly from the mountaintops of the Pacific states of Sinaloa and Sonora, then expanded to Nayarit, Jalisco, Guerrero, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, and Campeche. The irrigated harvest for mota ran from February to March; the natural harvest from July to August. All merca, merchandise, had to reach the border by fall, November at the latest. Americans didn’t work during the holidays.

The large, curving horn of Mexico was anchored on two great mountain chains, or cordilleras, both rising from north to south, one on the east facing the green Gulf of Mexico, the other sloping westward to the blue Pacific Ocean. Between these mountain ranges, a high central plateau tapered down with the horn to the Yucatán Peninsula. Eons ago, volcanoes cut the plateau into countless jumbled valleys with forests of pine, oak, fir, and alder. The coastal lands were tropically humid, but the plateau had a climate of eternal spring. It should’ve been eminently fit for man.

Instead, Mexico’s future would be full of conquests, dictatorship, revolt, corruption, and crime.

When Robert and Ronnie arrived in Laredo in 1991, the major crossings along the two-thousand-mile border between Mexico and America—from east to west: Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo, Juárez, and Tijuana—were controlled by “smuggling families” that straddled the border and charged a tax, known as a cuota or piso, which was in turn used to pay the bribes that secured the routes for trafficking in drugs and immigrants. Fights broke out between the families, and there was some spillover violence, but there were no cartels, not yet.

Patrol officers in Laredo PD seized large quantities of narcotics and saw some dead guys left in the front yard. But nothing too graphic. The young cops, making their nine dollars per hour plus overtime, were cocky. They had no awareness of the larger world; everything revolved around them. Places like Florida, Colombia, Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Washington, D.C., were a world away, and changing. Drug-war politics were in flux. In Laredo, Robert and his partners knew little beyond their squad cars.

As cops came up in PD, some set their sights on SWAT; others tried out state agencies like Child Protective Services and found that they didn’t mind dealing with domestic nightmares. Robert liked drug work because of the local impact. A drug arrest wasn’t mere pretext. You weren’t just taking a guy with dope off the street. That guy also committed assaults and robberies to get drugs. If the guy was a big dealer, maybe he used kids as drug couriers and to operate “stash houses,” the places where dealers kept their drugs and money. Robert would stop a guy with a gram of coke or a pound of weed, or bust a house that sold heroin to local Laredo addicts. He’d get his picture in the Laredo Morning Times perp-walking a guy to the local jail. He felt like he was “sweeping the streets of crime.” He’d turn on the TV, see some Nancy Reagan–type person telling everyone, “Say no to drugs!” and feel like Superman.

THE LUMP-SUM PAYOUT RONNIE GOT when she left the military took some weight off her and Robert’s life together. They paid cash for a mobile home in South Laredo. Robert’s salary covered bills.

Still, they were a young couple with two kids, trying to make it in a new city. There was plenty to fight about. One of about one thousand white people in a city where bloodlines and patronage determined jobs and social circles, Ronnie was more of an outsider than Robert. As a stay-at-home mom she felt isolated. Life in Laredo wasn’t fulfilling. That was their biggest fight: She wanted to get out. When she did go looking for work, she felt lucky to get hired at a doctor’s office, where she was told, “You know, I like it that you’re not from here.”

Later, Robert would learn to divide the cop persona from the father-husband. But in his twenties, the machismo kicked in at home. I’m the man and you’ll obey. I’m going out tonight. There’s nothing you can do about it. Ronnie was dominant herself, until she grew sick of fighting and relented. “Okay,” she told him one night, “have a good time.” Taken aback by her capitulation, Robert worried about what she was going to do when he got home. He rushed back an hour later. Is that all it takes? Ronnie thought.

If Robert’s bravado failed to impress his wife, his little brother Jesse saw him as a hero. Jesse, feeling as though he could please their parents only by matching Robert’s accomplishments, dropped out of high school in eleventh grade and came to live with Robert and Ronnie in Laredo, where he got a job as a high school security guard. Jesse wanted to become a cop, too, but he was young. Robert advised him to get an associate’s degree in criminal justice at Laredo Community College. But Robert hadn’t gone to college, and Jesse was eager to start a career. There were openings at the police academy in Uvalde, near Eagle Pass. In the summer of 1997, Robert gave Jesse some money, and his old service weapon, a .357 Magnum. Jesse completed the academy but failed the written test, then failed it again. If he failed a third time, he’d be barred forever from a job in Texas law enforcement.

Meanwhile, after hundreds of drug arrests, fourteen cars wrecked in hot-pursuit chases, and a dozen minor fractures, Robert was awarded Officer of the Year.

A week later, Jesse bused up to Wisconsin, where his parents were doing factory work that fall. He spent the weekend with them, showing no particular signs of depression, then returned to the family house in Eagle Pass and shot himself in the heart with Robert’s service weapon.

Rumors emerged in the aftermath of Jesse’s death. A girlfriend might’ve been pregnant. He might’ve been messing around with drugs, might’ve owed people money. Robert put his fist through a wall, then stalked around Eagle Pass looking for people to speak with about Jesse, until his father said, “Déjale.” Leave it. Don’t investigate. So Robert took Jesse’s prized possession, a Marlboro jacket he’d sent away for, and bundled up his grief.

The Officer of the Year Award came with an opportunity. The Drug Enforcement Administration offered Robert a role as a task force officer. He wouldn’t make the pay of a federal DEA agent. He’d remain a cop, collecting salary from Laredo PD. DEA agents, who had college degrees, made twice as much in base salary as task force officers. Agents also earned monetary awards for major investigations, sometimes as much as $5,000 per case. The only incentive for task force officers was overtime pay—an extra $10,000 or $12,000 a year for the crazy hours. Win an award, lose a brother. Get a promotion, make the same pay. But now Robert would have the power to investigate drug traffic and make arrests anywhere in the country. He talked to Ronnie. “I’ll travel and won’t see you or the boys much. But it’s temporary. I can bust my ass for awhile.” Eric, the older son, was in third grade; Trey, the younger, was in first. Ronnie knew this arrangement made her a single parent. “Okay,” she said. “Take four years.”

For a young cop who believed in the drug war, joining the DEA was a big step in his career. It would be nothing like he expected.

2

Flickering Candle

Freeze there: See Gabriel Cardona march backward, away from the stun grenade and the Laredo safe houses, away from the Texas jails and the Company lawyer, back to that zone of impunity. See la policía clear out a restaurant so an enemy ate alone, idle prey, practice for a new soldier. See a pickup truck: Hear the screams of the bound men inside who killed Gabriel’s boss’s brother fade to the whoosh-whoosh of towering flames. See Gabriel, months earlier, arrive at the training camp, primed for the work but not yet a frío, his aptitude raising eyes among la gente nueva, the new people.

And keep rewinding, back a decade, to Laredo, Texas, in the mid-1990s. It was as hopeful a season as there had been in the oldest ghetto of the poorest city in America. A city of new immigrants and Mexican-Americans whose mother country, next door, was finally set to democratize after seventy years of one-party rule. A city on its way to becoming one of the busiest trading posts of the world’s greatest economy.

September mornings arrived at a cool ninety-eight degrees—“the late-summer cold spell,” locals joked. Mrs. Gabriela Cardona—known among her children as “La Gaby”—rolled out of bed quietly. Best to let the drunk sleep it off. On her way to the bathroom, with its ceiling that caved in a little more each year but never broke, she slapped the feet of her four sons, who slept together on a queen-size mattress. “Es-school! Es-school! Es-school!” she yelled in her accented English, and flicked water on the boys—ages eleven, ten, six, and four.

Despite La Gaby’s troublemaking brother and her good-for-nothing husband, neighbors considered the Cardonas a capable family. La Gaby inherited an old family house across the river in Nuevo Laredo, and she occasionally collected rent on it. She worked hard, and always had a job. CPS never visited their address.

If she was going to have problems with any son, she doubted it would be with the second. Gabriel had started reading earlier than other children, consuming every volume of the Sesame Street series and Selfish, Selfish Rex, a parable about the virtues of sharing. He ran about in Batman shoes, scored perfect attendance at both regular school and Sunday school, and read the Bible. Teachers remarked on his generosity, and how he looked out for smaller kids.

“Oralé, al agua pato!” La Gaby yelled. Listen up, hit that water duck!

During elementary school mornings Gabriel showered with his older brother, Luis, while La Gaby shouted soaping instructions from the kitchen: “Cabeza, cuello, arcas, wiwi, cola, pies.” Head, neck, armpits, penis, butt, feet. Combing the boys’ hair into Ricky Martin pompadours, she repeated the instructions until they learned to do it themselves: “El partido por la orilla, lo demás pa’ca y levantas al frente.” The part should be on the side, the rest toward here, and raise it up in the front. Then Gabriel helped his younger brothers get dressed, ate a breakfast taco of egg and chorizo, grabbed his notebook, and ran outside, where a tree dropped sour oranges and threw shade on the multiplying kittens that shat in the dirt by the rusty gate in front of 207 Lincoln.

Situated on a bluff overlooking the Rio Grande, El Azteca—their six-square-block neighborhood known simply as “Lazteca”—was 250 years old. The streets were narrow, the sidewalks high: a closed feel. Early morning was Gabriel’s favorite time of day. Dawn came quiet in the hood, as cops and Border Patrol switched shifts. He preferred it to the chaos of Lazteca by night, when the streets came alive with the spotlights of beating helicopters and the squeal of tires as drug runners and coyotes—immigrant smugglers—tried to outrun the authorities.

Interstate 35, the biggest smuggling corridor in America, began a hundred yards from the Cardonas’ door. On the way to school—north along Zacate Creek, west through the I-35 underpass that led to J. C. Martin Elementary—Gabriel and Luis passed men coming off night shifts packing narcotics for the drive north, illegal immigrants looking for a ride to a hotel, and the daily queue outside the bondsman’s office. Such were the signs of Lazteca’s economic health. And like any friendly neighborhood, generosity was community. Fathers and boyfriends and uncles and brothers came home after a successful trip to Dallas, giving here, giving there, buying pizzas. La Gaby would tell the boys, “Vacúnalo!”—Get a lick out of him!

Uncle Raul, the smuggler who blasted speedballs, injecting heroin and cocaine at the same time, was always in and out of prison, but Raul taught Gabriel and his friends to play football. Gabriel was the quarterback. One of his homies from Lazteca, Rosalio Reta—younger by three years and shorter than a kitchen table—was always trying to prove himself to the older kids. He took big hits and sprang back up, smiling, his huge cheeks swelling like avocados around the upper-lip birthmark. They played violent video games like Mortal Kombat, and listened to the rap music of Tupac Shakur.

On the way home from school, Gabriel and Luis played along Zacate Creek’s slimy bank. If they came home stinking like fish, they received a beating from La Gaby, who always stood at the ready with an extension cord in hand, nose active. But she had a soft core. Gabriel and Luis’s best friends, the Blake brothers, were allowed to sleep over whenever they brought La Gaby a bottle of Big Red soda or a Coke. She cried when CPS moved the Blakes to foster care in Brownsville after their mother was picked up again for heroin.

Mr. Cardona was good for certain things. An out-of-work security guard, he took Gabriel and his brothers to the park for barbecues and out riding bikes. He played guitar and sang. On weekends they walked across the border to visit extended family in Nuevo Laredo, passing from the fresh air of America to Mexico’s wilder aromas: carne asada, horses, old leather. With air-pump guns, the cousins played “shooting.” Gabriel would catch pellets in the face but never relent. They called him loco, crazy.

GABRIEL’S AMERICANNESS GAVE HIM A special status south of the border. The North American Free Trade Agreement, which took effect in 1994, eliminated tariffs on goods traded between Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Not only could Wal-Mart now ship raw materials to Mexico, manufacture goods with Mexican labor, and reimport the finished product to American consumers without penalty, but it could also establish retail outlets in Mexico and drive mom-and-pop stores out of business. Wall Street smiled. Investment flowed. American goods lined the shelves of supermarkets and U.S.style department stores all over Mexico: Adidas and Kodak; Coke and Cheetos. Willie Nelson poured through speakers. All-day dry cleaners set a new pace. As cheap corn and wheat imports from the United States hurt Mexican farmers, rural Mexicans flocked to northern cities for work in maquiladoras, foreign-owned factories, where they became inundated with American consumer culture. McDonald’s, Pizza Hut, and even Taco Bell lit up skylines from Monterrey to Mexico City. The tendency was to idealize everything American and discount everything Mexican.

After family visits, when the Cardonas returned to Laredo, Gabriel’s father became insecure, then violent, having seen himself through the eyes of his Mexican family: an American who did no better than they did. Gabriel and Luis watched their drunk father beat their mother, punching her like a man would hit another man. When Gabriel went to school with a palm imprinted on his face, his teacher asked if he was okay. He nodded. He knew the rule: No te identificas. Don’t say anything.

One night, La Gaby stabbed their father with a kitchen knife, then kicked him out for good. Gabriel was proud of La Gaby for being strong. He resented his father for drinking while his mother worked, and didn’t consider his leaving any great loss. Though a sense of deep loss came a few days later, on Gabriel’s tenth birthday, when Tupac Shakur died from gunshot wounds. Pac was his perro, his dog. Even years later he would feel coraje, rage, at whoever pulled that trigger.

IN JUNIOR HIGH, GABRIEL WON certificates of excellence for outstanding performance in math and English. Several of his adoring female classmates remembered him as the person to beat in seventh-grade algebra. He had a head for numbers, and a talent for memorization. His English teacher asked everyone to memorize a song and perform it. Gabriel appeared in class with a fake diamond nose ring, and a blue handkerchief around his head. The class rolled in laughter as he sang Tupac’s “How Do U Want It?”

He quarterbacked the football team through two undefeated seasons, and dreamed of becoming a lawyer. In the summer between eighth and ninth grade he enrolled at Workforce Center, through the Texas Migrant Council, and made a hundred dollars a week. He gave money to La Gaby, and purchased Polo shirts and Tommy Hilfiger boots for himself. He bought a bus ticket to Brownsville to visit a girlfriend whose family had moved away. They went to South Padre Island and ate pizza. Gabriel Cardona appeared to be one of those rare Lazteca kids whose energy might take him somewhere other than prison. Looking at the industrious fourteen-year-old, no one could have imagined that the $896.10 he made during the summer of 2000 would be his first and last legal income.

NAFTA, meanwhile, meant huge changes in cross-border trade, with tens of thousands of trucks coming through Laredo every week. Laredo’s population doubled during the 1990s, making it the second-fastest-growing city in America after Las Vegas, and the largest inland port in the Western Hemisphere. More than 75 percent of Fortune 1000 companies invested in Laredo’s transport facilities that warehoused Mexican goods before they headed north.

But aside from some extra minimum-wage jobs in the warehouses, none of the new revenue seemed to make it into the pockets of the working class. With a median income 30 percent below the national average, and 38 percent of its residents living below the poverty line, life for most of Laredo, still a front-runner for poorest city in America, had changed little after NAFTA’s passing. Despite the new orgy of commerce, it remained a giant, unimproved truck stop.

If the city of a quarter-million people didn’t look as poor as it was on paper, it was because the black market buoyed the legitimate one. Many of Laredo’s small businesses—perfume and toy stores; used-car lots and restaurants—were money-laundering fronts. The Mexican Mafia, a California gang with a strong Texas presence, owned slot machine halls known as maquinitas, and a bustling chain of beer drive-thrus, Mami Chula’s, staffed by bikini-clad teens who accepted tips like strippers. Other big gangs, such as the Texas Syndicate and Hermanos de Pistoleros Latinos, known as HPL, also owned businesses. The tallest building in town belonged to the DEA.

Gabriel stopped looking forward to their Mexico visits. His family didn’t have much, but he still felt bad going across in his Sunday best to see cousins who had nothing. Some of them picked pockets, washed cars, or performed sidewalk spectacles for tourist change. He did like sneaking out of church with his cousin, putting chewed gum on a stick, and fishing cash from the donation box. But Mexico, he felt, was dirty. Flies buzzed around garbage. He smelled urine, saw gang graffiti on brick walls, and watched plastic bags blow against fences, trapped like wounded birds. He didn’t like having to be careful where he sat or roamed. His opinion would change, later, when he got some money. But for now he appreciated America for its relative glimmer.

When high school started, he hoped to become quarterback of the junior varsity football team. No Laredo team had ever made it past the third round of state playoffs; in most years, Laredo carried the dubious distinction of being the largest city in America not to have a football player win an athletic scholarship at any level. Still, a Laredo kid was a Laredo kid: five foot seven, not very fast, but played hard. Gabriel had read Friday Night Lights, the famous book about Texas high school football, and he dreamed of entering that world, of experiencing the American rite, as H.G. Bissinger wrote, of playing under the “full moon that filled the black satin sky with a light as soft and delicate as the flickering of a candle.” He dreamed of something glorious to fill the blah of life.

The boy grew up handsome, talented, and popular. His ego knew little of rejection. So when the coach benched him in favor of a sophomore, he quit. It was a decision in which loads of portent would later be vested. Had he been a starter, he would’ve stayed in football, remained after school for practice, and kept getting the grades required for participation. Instead, after leaving practice that day, he hooked up with two brothers connected to Laredo’s street gang scene, smoked pot for the first time, and drove around vandalizing houses.

A few days later some terrorists knocked down some buildings in New York.

3

My Dad Does Drugs

Shortly after September 11, Robert Garcia was in the doctor’s office getting another round of steroid injections. His full head of black hair survived military service, the threat of a dishonorable discharge, early fatherhood, the struggles of marriage, and the stresses of a street cop. Now, at thirty-three, the thick hair was coming out in quarter-size patches.

It was pretty clear that drugs were to blame.

When Robert joined DEA as a task force officer, he started traveling up I-35 to “the checkpoint”—a kind of second border crossing twenty-nine miles north of Laredo where Border Patrol agents applied random levels of scrutiny to vehicles, more so to cars and trucks driven by Hispanics. Connecting with the entire system of U.S. interstates, I-35 ran up through San Antonio, Austin, Dallas, Oklahoma City, Des Moines, and Minneapolis. But it all started at the checkpoint, where the largest busts were made. Sometimes tons of narcotics were seized. As a street cop Robert made small drug busts within the city. His first months at DEA gave him a wider lens. Where, he wondered, is all this stuff coming from?

By 2000, six years after NAFTA was implemented, trade between Mexico and the United States had tripled, to $247 billion, and the four bridges that connected Nuevo Laredo to Laredo saw 60,000 trucks go north per week. Because every truck stopped for a search was a drag on global commerce, NAFTA eased friction for smugglers, too. Blizzards of white powder now came packaged in bounties of fresh citrus; boxes of plastic bananas, five-dollar sunglasses, and spice jars; as well as countless other goods. Some traffickers hired trade consultants to determine what merchandise moved across the border most swiftly under the new regime. Did a perishable get through quicker than a load of steel?

In the basic drug-interdiction formula, the DEA busted a smuggler coming across and offered to reduce his charges in exchange for his help busting the northern buyer—in places such as Detroit, Brooklyn, and Boston. To account for the time lost during interdiction and to ensure that the deal seemed genuine to the northern buyer, the truck was then flown north on a DEA jet. Or, if there was enough time, an undercover agent, like Robert, would drive the drugs to the point of sale. The DEA called these busts “controlled deliveries.”