9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

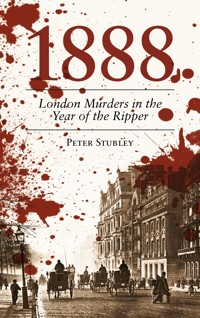

In 1888 Jack the Ripper made the headlines with a series of horrific murders that remain unsolved to this day. But most killers are not shadowy figures stalking the streets with a lust for blood. Many are ordinary citizens driven to the ultimate crime by circumstance, a fit of anger or a desire for revenge. Their crimes, overshadowed by the few, sensational cases, are ignored, forgotten or written off. This book examines all the known murders in London in 1888 to build a picture of society. Who were the victims? How did they live, and how did they die? Why did a husband batter his wife to death after she failed to get him a cup of tea? How many died under the wheels of a horse-driven cab? Just how dangerous was London in 1888?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Prologue 1 January, 1888

1 Journey to the Centre of the Earth

2 The Streets of London

3 Life in the Suburbs

South

North

West

East

4 Life in the City

Markets

Pubs

5 In Darkest London

6 Policing the Metropolis

7 The Curse of Scotland Yard

8 Two Mysteries

A Nagging Toothache

At the Pleasure Grounds

9 Home Sweet Home

The Lady’s Maid

The Banker’s Wife

Trouble and Strife

The Neglected Wife

The Triple Event

10 The Unfortunates

11 Under the Knife

12 Dead Babies

13 Children

The Runaway Soldier

One Night in Judd Street

At the Workhouse

A Telegram for Mr Spickernell

Want and Murder

Ten Shillings

14 Teenage Gangs in London

15 Madness

16 Death

Epilogue 31 December, 1888

Appendix

Bibliography

Notes

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

Prologue

1 JANUARY, 1888

As the church bells rang in the New Year across central London, a woman lay dying. Her left arm had been sawn off and her face was swollen with bruising to her forehead and right eye. Elizabeth Gibbs was slowly succumbing to shock and exhaustion despite the efforts of the medical staff at St George’s Hospital in Hyde Park. Outside the temperature was dropping towards - 4° Celsius and the frost lay so thickly on houses, trees and roads that it appeared as if snow had fallen. The capital was in the middle of its coldest winter for thirty years. Later that morning thousands of people would swarm across the frozen ponds and lakes of the city, happy to risk a cold bath when the ice gave way. Life droned on regardless as Elizabeth Gibbs slipped away at 2 p.m. that afternoon, becoming the first homicide victim of 1888. 1

By the end of the year the police would count a total of 122 cases, of which twenty-eight were classed as murder and ninety-four as manslaughter. More than half of the victims were female, and eight were said to be of the ‘unfortunate’ class, living on the margins of existence by selling their bodies for a few pennies at a time. Five of those eight are generally accepted to have been the victims of a single serial killer who would never be identified, let alone arrested or put on trial. The newspapers called him Jack the Ripper, and were only too happy to promote the legend to help make them a profit. And it did so, handsomely. But among the acres of newsprint devoted to the unknown murderer, the Victorian public would have read reports of other victims who would not be remembered over 100 years later. Some of these cases would be mentioned in Parliament and in the pages of The Times, but they were far less sensational when compared to a knife-wielding maniac loose on the streets with a lust for blood.2

Elizabeth Gibbs was one of these other homicide victims, a respectable married woman living in the wealthy area of Belgravia, on a road that was home to Alfred Tennyson, Ian Fleming and Mozart over the years. She was sixty-eight years old and was enjoying a pleasant walk along Grosvenor Place, near Buckingham Palace, when she was knocked down and run over by a horse-driven van carrying bottles of mineral water. Her arm was so seriously injured that it had to be amputated by a surgeon in an unsuccessful attempt to save her life. Following her death, police charged a forty-three-year-old delivery driver from Shoreditch called Alfred Winwood with manslaughter. Winwood was convicted and sentenced to six months’ hard labour.

It is just one story among dozens from 1888, and the cast list includes all ranks and classes of society from every corner of the city; from the unnamed newborns dumped on the street to the seventy-one-year-old retired major shot dead at his front door, and the Jewish immigrant working for slave wages in the East End to the Englishwoman living in relative comfort in the West End.

Murder is the ultimate crime, and a particularly shocking one can attract the attention of Queens and prime ministers and help bring about real change. On the other hand, some suspected murders were virtually ignored by the press and public because they were so commonplace in nineteenth-century Britain. But each case can illuminate hidden parts of society and provide colour to those areas well charted in textbooks. Not just by telling the stories of the victims and their killers but also the places that the two met, the cause of death, the action or inaction of the police and the prosecuting authorities, and the reactions of judges and juries. The historian Richard Cobb wrote that ‘famous murder trials light up the years and give a more precise sense of period than the reigns of monarchs or the terms of office of presidents’. What might be called ‘murderography’ has the potential to describe a specific period of time better than any other kind of historical study. This book aims to use the stories of those victims of homicide in one year in late-Victorian London to illustrate the period, and to hopefully give an impression of what it might have been like to live through one of the most exciting eras in our history. 3

At this time the British Empire was at the height of its influence and power – economically, politically and culturally. London was its capital, and therefore the capital of the world. Its inhabitants included: Florence Nightingale; H.G. Wells; George Bernard Shaw; Arthur Conan Doyle; Oscar Wilde; the American author Henry James; a young student by the name of Gandhi; the Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick; a six-year-old Virginia Woolf; and the fourteen-year-old Winston Churchill. And ruling over all was Queen Victoria, Empress of India, who had celebrated her Golden Jubilee in the summer of 1887 with a vast procession through the streets, and a banquet for kings and princes from across the world. The affection and loyalty of her subjects was obvious. One of the spectators that day summed up the general mood by writing in her diary: ‘We are filled with enthusiasm and loyalty. What an Empire! What a City! What an Age! What a Queen!’ 4

Queen Victoria had celebrated the arrival of 1888 by remembering the previous twelve months as being ‘so full of the marvellous kindness, loyalty and devotion of so many millions’. She wrote in her journal that there was ‘not one mishap or disturbance, not one bad day … never never can I forget this brilliant year.’ But twelve months later her mood was very different. This time she marked ‘the last day of this dreadful year, which has brought mourning and sorrow to so many, and such misfortunes, and ruined the happiness of my darling child’.5 Although the Queen was referring mainly to the death of her son-in-law, the German Emperor Frederick III, there had been little to celebrate in 1888. The economy was still struggling through a depression which began in the 1870s, protestors continued to take to the streets, workers went on strike, and the population was gripped by moral panic over a series of murders without parallel in history. For this was the Year of the Ripper.

1

JOURNEY TO THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH

The RMS Ormuz was the fastest ship in the world. It was 482ft long, 52ft wide, and weighed more than 6,000 tons but its 8,500hp steam engines could propel it halfway round the globe in less than four weeks. Not so many years earlier the same trip would have taken three months. It was equipped with berths for nearly 400 passengers – 106 in first class, 170 in second and 120 in steerage – as well as two saloons, two promenade decks, a library, a drawing room, a coffee room, two smoking rooms and a hospital. No wonder that its proud owners, the Orient Line, had seen fit to boast: ‘Were the world a ring of gold, Ormuz would be its diamond.’ But for John King it was just a means of getting home.6

The thirty-nine-year-old chemical engineer was making the voyage from Australia to London with mixed emotions. Just four months earlier, in April 1888, he had arrived in Sydney with high hopes of finding his fortune in the fabled ‘workers’ paradise’. The auspices had seemed favourable, for that year marked the centenary of the first landing of 1,350 colonists at Sydney Cove. Alas, it had not worked out as he expected and he had decided to return home to his wife, Mary, and their two young children, eight-year-old John Jr and seven-year-old Alice, in Rutherglen, Lanarkshire, not far from Glasgow and the Govan shipyards where the Ormuz was built in 1886.

His journey took nearly seven weeks. After leaving Sydney on 1 August 1888, the Ormuz called first at Melbourne and Adelaide before sailing across the Indian Ocean towards Egypt, passing from the Southern Hemisphere to the Northern and leaving the Southern Cross behind. At Suez they took on more coal for the engines before navigating the 86 mile-long canal between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean.7 After stopping off at Naples the ship rounded Spain, battled through the gales and stormy seas of the Bay of Biscay and gave its passengers their first sight of England through the fog at Plymouth. Two days later it was powering against the flow of the Thames towards the city at the heart of the British Empire. London, a metropolis of more than 5 million inhabitants, was also the symbolic centre of the world, where east meets west at zero degrees longitude.8

Finally, on the morning of 11 September 1888, the ship pulled into Tilbury Docks in Essex; it had been built two years earlier at a staggering cost of £2 million.9 John King stepped on to dry land and began the final leg of his journey by train, first from Tilbury to Fenchurch Street station, and then from St Pancras to Glasgow. It was a far less glamorous arrival than that of a foreign student from Bombay two weeks later. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi sauntered off the SS Clyde in a white flannel suit purchased specially for the purpose. Gandhi wrote in his autobiography: ‘I found I was the only person wearing such clothes … the shame of being the only person in white clothes was already too much for me.’ Gandhi travelled by train to the luxury Victoria Hotel, and quickly bought a new outfit and a 19s chimney-pot hat at the Army & Navy Stores, determined to appear the quintessential ‘English gentleman’ during his three-year law course at the University of London.10

By the time John King arrived at the impressive red-bricked edifice of St Pancras station he was part of a merry band of twelve fellow passengers from the Ormuz. Most of them were already drunk and singing loudly as they crammed on board the 9.15 p.m. night train to Glasgow. Joining King in one of the third-class compartments were three fellow Scotsmen: John Mattison and Charles Lee, who had both worked on board as firemen, and twenty-two-year-old stowaway James McKill, the son of a chemist from Hamilton.11

Such was their state of intoxication that nobody could remember what exactly started the argument between King and McKill. ‘They seemed as if they were going to take off their coats,’ remembered John Mattison, ‘I don’t know whether they did.’ Mattison got out at the next stop and joined his crewmate Charles Lee in the other carriage. From that point everything became a little hazy. He woke up the next morning in the Leicester Royal Infirmary, having accidentally headbutted the window, smashing the glass and cutting his head in the process. Another, more sober, witness believed the argument was between King and Mattison, although McKill had certainly offered to fight anyone who felt they were up to the challenge. King’s pockets were bulging with bottles, which he claimed were lemonade. The whisky was in his baggage, he said, but there was no time to retrieve it before the train set off. Whatever the truth, from Kentish Town onwards King and McKill were alone together in the same compartment. When the train reached the next stop at Bedford only McKill remained, lying full length on the seat, dozing. When they reached Glasgow the next morning, nobody noticed that John King had gone missing.

At 6 a.m., about 100 yards from Finchley Road station in north London, a signalman found two shirts and a cap by the side of the tracks. John Cockayne checked there was nothing in them before going on duty. Just over an hour later, three-quarters of a mile down the track towards London, platelayer William Franklin was walking through the Belsize tunnel carrying out an inspection of the line. Near one of the air shafts, half a mile from the London end, he saw a body between the rails and the wall. Its head was missing. Or rather about two-thirds of it had been sheared off and bits of brain and jaw had been scattered over the tracks. Further up the tunnel Franklin also saw a mark on the slimy black brick wall, as if a finger had been drawn along it. The mark began at a height of 7ft 4in and gradually dropped over a distance of about 10ft, at which point it seemed as if the body had collided with the wall, tumbling over and over for another 28ft before coming to rest. Franklin alerted the stationmaster before returning to the scene to move the body to the platform at Haverstock Hill to await the arrival of the police.

Inspector Somers of the Y Division quickly established that the dead man was John King. In a pocket was a ticket to Glasgow, a number of letters, a silver watch and chain, and two purses containing £3 9s 3d, along with papers indicating he had just come from Australia. His clothes and hands were black with muck from the tunnel, but there was no blood on them, and only a small tear to the left sleeve of the coat. Other than the catastrophic damage to the head there were only a few other small scuff marks on the knee and thigh. The doctor who examined him saw no evidence of any struggle. He had certainly not been robbed. Everything pointed to a tragic accident. There was also a suggestion that King had wanted to get two bottles of whisky from the luggage compartment further down the carriage, but did not have time at St Pancras station. Had he made a foolhardy attempt to retrieve his whisky by clambering along the side of the train? The jury at the inquest at St Pancras Coroner's Court seemed to think so, and after commending the police returned a verdict of accidental death.

The twist in the tale came only a few days later when the story appeared in the Scottish Reader newspaper. Hugh Mickle, a greengrocer from Kilmarnock, read the report and realised that he had been on that very same train with his friend George Cowan. They had entered a third-class smoking carriage and started a conversation with a young man on his way to Glasgow. This fellow was keen to talk, mentioning how he had just come off the boat from the Colonies. Tall stories, mostly. But one of his yarns was particularly memorable – earlier in the journey he had got in a fight with a stranger and had thrown him out of the train. He then took off his shirts because they were torn and stained with blood and threw them out the window as well. ‘I asked him what the gentleman was like,’ said Mickle. ‘He said he was a gruff sort of man, stouter than himself.’ Mickle declined the offer of a swig from the man’s bottle and noticed that the passenger had a bruise on his right cheek. There were also small bloodstains on the window next to the platform and on the floor. ‘He said he had got a blow on his mouth from the strange man,’ Cowan later recalled, ‘and that the blood came from a spit out of his mouth.’ The two friends from Kilmarnock advised the traveller to try to wash his face and get a shirt before he went home to see his mother. They hadn’t taken his boasts at all seriously and parted with him on good terms at St Enoch’s station in Glasgow half an hour later. ‘He told us a good many yarns,’ said Cowan. ‘In fact I put it down as a yarn from first to last.’ Yet now that they knew of events further down the line in London, it seemed that this was a case of murder.

Thirty-four years earlier the first-ever murder on a British railway had caused uproar in the press – Thomas Briggs had been beaten about the head, robbed and dumped out of a train in Hackney, east London. Due to the subsequent chase of the suspect across the Atlantic, the case had been an international sensation. When the killer Franz Muller was arrested he was carrying Mr Briggs’ gold watch and his hat. Muller’s own, cheaper, hat had been discarded. By contrast, the case of John King was an altogether more muted affair, particularly after the inquest. But now history seemed to be eerily repeating itself, for John King’s soft felt hat was missing. The sailor’s cap and shirts found on the railway line must have belonged to the killer.

Inspector Bannister, who had been happy to accept that the death of John King was a tragic accident, now reopened the investigation. He took statements from Mickle and Cowan, and on 21 September went in search of James McKill.

As it happened, McKill had ignored the advice to clean himself up and had proceeded to drink himself into a stupor. He was found lying shirtless in Eglinton Street, Glasgow, and was taken off to the police station to sleep it off. The next day he was brought before the magistrate and fined 5s, but as he only had 1s 10d on him, he was locked up for four days. On his release he had little option but to return home to his parents in Hamilton. It was an unexpected homecoming, but even more unexpected was the visit of Inspector Bannister on 21 September. The detective declared:

I have come to make inquiry about John King, who is said to have ridden with you from Kentish Town station in a third-class carriage on the night of the 11th, and whose dead body was afterwards found on the line in Haverstock Hill tunnel. You are not called upon to make any statement, and you need answer no questions, but if you do I will write it down, and in the event of any charge being made against you, it may be used against you.

McKill, described as a short man with close-cut hair and sharp, intelligent appearance, was happy to give his side of the story. He knew John King as a passenger on the Ormuz, but after they had got on the train at St Pancras McKill had fallen asleep and had no idea if anyone else had been in the same carriage. He denied making any confession to Mickle and Cowan or throwing his shirts out of the window. He claimed that he had actually sold his shirt in Glasgow for 1s so that he could buy a drink. Nonetheless there was enough evidence for him to be charged and returned to London. On the way there Bannister asked where he had got the felt hat found in his home. ‘I know that is the dead man’s hat,’ he replied. ‘I had a cap. I don’t know what became of mine.’ When McKill tried on the cap found on the railway line it appeared to fit him perfectly. ‘Yes, that’s mine,’ he replied.

The justice system was much quicker in the late nineteenth century than it is today. Inquests into suspicious or unexplained deaths were usually held within a few days, and coroners had the power to commit suspects for trial. At the same time, the suspects could also be brought before the magistrates at the local Police Court. Either way, cases of murder or manslaughter were usually heard at the Old Bailey within one or two months. If the charge was approved by a Grand Jury, the suspect would stand trial.

McKill’s trial began on 26 October. Under the law of the day, McKill was not allowed to give evidence and had to rely on the skill of his barrister Charles Gill. His defence was that John King’s death was an accident and that the victim must have got out of the moving train himself in a state of extreme intoxication. ‘The story about there being a fight and the prisoner having thrown the deceased out of the train was too absurd for a moment’s belief,’ Mr Gill was reported to have told the jury, ‘particularly when it is remembered that the deceased was the bigger and stronger man of the two, and besides, the quarrelling and the fighting and the throwing out would all have been done, if the story were true, within three minutes and a half.’ If it was true, then one would have expected to see signs of a desperate struggle. Mr Justice Cave advised the jury that if they thought McKill’s confession was simply the ravings of a drunken man then they ought to acquit. Even the prosecutor seemed unenthusiastic about the case. The jury did not even bother to leave court and after two minutes of hushed conferring in their box they returned a verdict of not guilty. McKill was a free man.

If this seems an anticlimax, it serves only to demonstrate that not every story has a clean-cut ending. Suspicion and a host of unanswered questions are not enough to convict a man of murder. Neither was the explanation of a tragic accident satisfactory. The victim’s family did not recognise John King as the type of man who would recklessly climb out of a moving train to fetch a bottle of whisky. Before his trip to Australia he had been teetotal and an unlikely brawler. Now he was dead, and his wife Mary had to look after his two children alone. She moved back home with her father and brother in Rutherglen and in 1892 got married to a blacksmith. Sadly tragedy had not yet finished with the family. Seven years later, John King’s son died at the age of nineteen from appendicitis.

James McKill married a year after his acquittal and had at least three children. His father died in 1893, followed by his mother in 1915. In 1920, at the age of fifty-five, he appears to have emigrated to America and settled down in Cook, Illinois, and found work as a janitor at an oil company. His son Robert got a job on the local electric railway.12

2

THE STREETS OF LONDON

Londoners in 1888 were astounded by the changes that had taken place since the start of the nineteenth century. As one observer noted, ‘Old London is going, going, indeed, has well-nigh gone.’ It was now an urban giant extending well into Surrey, Middlesex and Kent, and its centre had been furnished with new landmarks like Trafalgar Square, Buckingham Palace, the Royal Courts of Justice, the National Gallery and the Houses of Parliament. Then there were the restaurants and theatres, department stores and tea shops, and hotels boasting elevators, telephones and electric light in all bedrooms. It was a sightseer’s paradise. The guidebook, London of To-Day, summed up the mood in their 1888 edition:

Since the end of the eighteenth century London has undergone a marvellous change. The monster Metropolis, which is still swelling every year – to which, indeed, many thousand houses, forming several hundred new streets, covering a distance not far short of a hundred miles, were added but a year ago – which is increasing in a way which makes it bewildering to contemplate, not its final limits, but where those limits will reach even in the near future: this monster London is really a new city.13

Of course, not everybody agreed. The writer Ouida argued in an article for Woman’s World in 1888 that:

… for a city which is in some respects the greatest capital of the world, the approaches to London are of singular and painful unsightliness … The streets are dreary, although so peopled; the sellers of fruit or flowers sit huddled in melancholy over their baskets, the costermonger bawls, the newsboy shrieks, the organ-grinders gloomily exhibit a sad-faced monkey or a still sadder little dog; a laugh is rarely heard; the crossing-sweeper at the roadside smells of whisky; a mangy cat steals timidly through the railings of those area-barriers that give to almost every London house the aspect of a menagerie combined with a madhouse … To drive through London anywhere is to feel one’s eyes literally ache with the cruel ugliness and dullness of all things around.14

Nevertheless this new, expanding city required a transport system to match. One by one, the great railway stations were opened: London Bridge (1836), Euston (1837), Paddington (1838), Waterloo (1848), King’s Cross (1852), Victoria (1860) and Charing Cross (1864). Sewers were constructed. Bridges were built over the Thames and tunnels were dug under it. People swarmed from one end of the city to another by foot, bicycle, trains and horse-drawn cabs, omnibuses and trams.15

All this travelling posed increasing danger to the pedestrian, particularly at the busiest intersections. Piccadilly Circus, which was originally a crossroads, stood at the junction of the two major new thoroughfares, Regent Street and Shaftesbury Avenue, the latter being completed in 1886. The great illuminated advertisements were yet to go up, and the statue of Anteros, the Angel of Christian Charity, would not take its place at the centre of Piccadilly Circus for another five years. What it did have was an endless flow of horses, human beings and goods surging and halting under the direction of dedicated police constables determined to prevent everything from toppling into chaos. It was said that:

… at the movement of a gloved hand, a stream of cabs, buses, carts, waggons, barrows, drays, traps, carriages – in fact, every variety of conveyance upon four wheels or two suddenly comes to a standstill, just to allow a lady to pass! The lady has as much right to passage-way as the owner of the proudest horseflesh, and it is on this principle that the policeman acts – everybody in turn.16

In an age before the combustion engine and exhaust fumes, the interchange was filled with the shouts of drivers, clattering hooves and the snorts of horses, with manure dropping from the back end. Every few minutes another omnibus passed through the vortex on its way to Hammersmith, the Strand, Liverpool Street, London Bridge, and West Kensington. This was the heyday of the buses, ‘the most convenient and the cheapest form of travelling from one London street to another’. They ran from early morning to midnight, charging fares of between 1d and 6d depending on distance and time. The first omnibuses, drawn by three horses, travelled between Paddington and Bank and had space for twenty passengers but, in effect, they were little more than a box on wheels with a few windows and a door at the back. By the 1860s the business was dominated by a French-owned outfit, the London General Omnibus Co., but from 1881 they came under increasing pressure the London Road Car Co. The Road Car buses boasted lower fares and more comfortable vehicles, and printed tickets to prevent fraud by conductors. To stand out from the crowd they flew a small Union Jack, a patriotic dig at their rivals. By 1888 the Road Cars were ferrying 22 million passengers a year compared to the London General Omnibus’ 95 million. While this competition meant passengers could travel across London for as little as a penny, it occasionally threatened to turn into a hair-raising race.

When the conductor rang his bell the intelligent horses settled into their collars without any word of command, and the passengers took a sporting interest in the driver’s efforts to pass the omnibus of the rival company; London General Omnibus Company versus the Road Cars with their little fluttering flags. And everywhere under the horses’ noses the nimble orderly boys scuttled about on all fours, with their little scoops and brushes, trying to keep the pavement of our imperial city comparatively clean, and in wet weather failing malodorously.17

A similar scene unfolded on the afternoon of Saturday 4 February 1888, as Augustus Maude boarded a road car at Piccadilly Circus to get home to West Kensington. He climbed to the top deck and took his place at the front looking out over the horses as they headed west towards the most fashionable quarters in London. The famous thoroughfare of Piccadilly lay before him – Wren’s brick Church of St James, Byron’s old rooms in the Albany suites, the Royal Academy at Burlington House, the Arcade, and the Egyptian Hall where Maskelyne conducted his theatrical magic shows. Gathering pace down the slight gradient, the road car settled in a few yards behind a rival London General Omnibus as Green Park opened up on the left-hand side. To the right were the aristocratic windows of the millionaire Angela Burdett-Coutts on the corner of Stratton Street, an ideal viewing platform that, according to Queen Victoria, was ‘the only place where I can go to see the traffic without stopping it’.18 Close to the junction with Half Moon Street, Maude noticed the omnibus in front slow down, as it stopped to allow three ladies get off. The driver of the Road Car pulled his horses on to the wrong side of the road to overtake, slammed into an elderly man crossing the street and ran right over his legs.

Over at No.94 Piccadilly, in a grand building marked out with a distinctive ‘In’ and ‘Out’ on its entrance and exit gates, Lord Charles Beresford was enjoying a leisurely afternoon at the Naval and Military Club. ‘Charlie B’, as he was known, was the Irish second son of the Marquess of Waterford and an MP who had only three weeks earlier resigned from his post as Junior Sea Lord of the Admiralty in protest at what he saw as Britain’s ill-preparedness for war. By contrast, he was admirably prepared for action on this occasion. On hearing the commotion outside the club, he strode to the scene of the accident, put the injured man in a cab and sent him to St George’s Hospital on Hyde Park Corner.

The injured man was James Langley, a sixty-eight-year-old widower who had been walking through Green Park and was crossing the road to get home to Shepherd Market in Mayfair. His accident featured in a long list published by a weekly newspaper, which included: a woman run over by a Road Car near Westminster Abbey; a four-year-old boy who knocked a kettle of boiling water over himself; a man who fell into a tub of boiling water at work; a boy whose hand was crushed at a printing machine; the suicide of a young watchmaker’s wife using cyanide; and a dock worker whose legs were crushed by a heavy case. Sadly, James Langley would not recover. Surgeons amputated one of his broken legs but the shock to his body was too great and he died two days later. It had been a successful life. He had been born and married in Berkshire but in his twenties had moved to London to make his way in the world. By 1881 he was a master carpenter employing five men. On his death, he left a personal estate of £650 to his eldest son, Isaac.

Every year nearly 150 people were run over and killed in London, and more than 4,500 were injured.19 The overwhelming majority of deaths did not result in criminal proceedings, the modern charge of causing death by dangerous or reckless driving being unavailable until 1956. It was murder, manslaughter or nothing. In the case of James Langley the inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental death, but at the Police Court the prosecution argued that the omnibuses were racing down the hill at up to 10mph in an attempt to be the first to pick up passengers. The magistrate sent the driver of the Road Car omnibus to trial for manslaughter at the Old Bailey. On 2 March 1888, Walter Prescott, twenty-eight, was acquitted after a number of witnesses, including passenger Augustus Maude, testified that the buses were not racing and that the driver had done all he could to avoid an accident after the vehicle in front pulled up suddenly without warning. He may have been guilty of negligence, the judge remarked, but it was not gross criminal negligence.20

The competition for fares between rival drivers was so fierce that it occasionally erupted into physical violence. Frederick Sheward, forty-three, was well known among other Hansom cab drivers for constantly complaining that they had been ‘rubbing up’ against his vehicle. On Saturday 22 September he returned to the busy stand in Charing Cross Road at 10 p.m. to find his paintwork had been scratched. This time he picked on fifty-year-old James Williamson, a ‘rigger’ who looked after the cabs on the rank.

‘Look at my cab, it is disgraceful, it is always the same every night as I come back,’ Sheward ranted.

‘I have not done it, I have to look after my living,’ replied Williamson. ‘It must have been done elsewhere.’

‘You ought to be ashamed,’ continued Sheward.

The argument went back and forth for several minutes until another cab driver, Henry Matthews, decided to intervene and shouted, ‘Leave the old man alone.’

Sheward replied, ‘Mind your own business, what has that to do with you?’

Matthews then got off his own vehicle, walked up to Sheward and punched him in the face, giving him a bloody nose. This delighted Williamson, who began cheering and taunting Sheward, ‘You’ve got what you deserve you bloody monkey.’

As Matthews left in his cab, Williamson and Sheward continued to argue. Williamson was threatening to hit the other man with his walking stick. ‘I’ll knock your bloody head off.’

At this, Sheward hit Williamson in the face, knocking him to the ground near the junction with Great Newport Street. ‘Take that,’ he added, before walking off.

Williamson, who was unconscious and bleeding from a head wound, was placed into a cab and taken to Charing Cross Hospital at around 11.15 p.m. An hour later he suffered two epileptic fits. Williamson died that morning and a post-mortem revealed he had suffered a fracture at the base of his skull and brain damage from hitting his head on the ground as he fell.

Sheward was arrested at his home in south Lambeth at 6.40 a.m. on 23 September by Detective Sergeant Henry Scott.

‘I have come to see you with respect to a man who was knocked down last night,’ said Detective Scott.

‘Yes, he was messing about my horse’s head,’ replied Sheward. ‘He struck me first, and I struck him.’

Sheward was put on trial for manslaughter at the Old Bailey the following month but was acquitted after several witnesses admitted that Williamson was a ‘quarrelsome man’. Another cab driver, William Andrews, also told the court that Williamson struck out at Sheward with his walking stick before being knocked down. By contrast Sheward was said to have an ‘excellent character as an honest, sober and peaceful man’.21

While most of the busiest roads were to be found in the centre of London, crossing the street in an era before traffic lights and zebra crossings posed dangers to the pedestrian all over the city. One guidebook for tourists noted that:

Crossing, although a matter that has been lately much facilitated by the judicious erection of what may be called ‘refuges’, and by the stationing of police constables at many of the more dangerous points, still requires care and circumspection … One of the most fatal errors is to attempt the crossing in an undecided frame of mind, while hesitation or a change of plan midway is ruinous.

However, it added that, ‘to the wayfarer London is the safest promenade in the world’.22

On the evening of Saturday 28 July, Ann Rowley, a seventy-four-year-old widow, was on her way to Peckham after visiting her grandson near Charing Cross. She walked to Westminster and paid 2d to board the tram heading to New Cross. As it reached the High Street opposite Rye Lane the passengers could hear a band playing loudly outside a butcher’s shop, celebrating its first day of business. Ann Rowley stepped off the back of the tram and then went to cross the road behind it. She barely had chance to respond to the rough cry of, ‘Get out of the way’, before a Hansom cab coming the other way slammed into her at 9mph. She was flung 10 yards along the road before the wheel of the cab ran over her right leg. If the driver knew what had happened, he appeared not to care and continued driving.

‘I cried out to the cabman to stop, and ran after him, holloaing as loud as I could,’ recalled one witness, the plumber William Graham. ‘I said to him “Mate, stop! You have run over that woman”.’

The driver had turned round and replied, ‘Go to buggery’, before setting off again with a slash of the reins. Others now joined in the chase and it was only through the force of an outraged mob that the cab was brought to a halt. The driver seemed more concerned about losing his two existing fares than the condition of Ann Rowley.

‘He came back with a great crowd of people,’ remembered another witness. ‘They were all holloaing at him, and there was a great deal of confusion and excitement – he refused to turn the fare out and assist the lady into the cab, and this put the people out.’

Twenty-five-year-old George Ernest Holden was a butcher by trade. Although he was licensed to drive a cab, he had no vehicle of his own and had taken one without permission from the rank in Peckham High Street.23 Most people who saw him that day took the opinion he was ‘silly’ drunk, the kind of condition brought on by two or three glasses of beer. He still hadn’t sobered up by the time he arrived at the shop owned by Ann Rowley’s grandson, Robert Portwine, off St Martin’s Lane. As the lady was taken out of the cab, Holden kept repeating, ‘It was not my fault, missus’, and, perhaps excited to find that Mr Portwine was also a butcher, went around everybody in the premises trying to shake their hand. When he was arrested a few hours later, he was back in the Greyhound pub in Peckham.

Ann Rowley ended up at Charing Cross Hospital with a broken right leg. It was put in splints but two weeks later had to be cut off because the wound wasn’t healing and had begun to rot. She died on 25 August, nearly a month after the accident. The inquest jury returned a verdict of manslaughter against Holden, but following his trial at the Old Bailey, he was found not guilty. Perhaps the jury were swayed by his claim that Mrs Rowley had assured him that it was not his fault. His barrister also made the point that the doctor who first attended the injured lady had not been called to prove that Holden was under the influence of drink. As the Hansom had been driving at a ‘perfectly proper rate of speed’, there was no negligence proved.

Then, as now, the elderly were at particular risk from London traffic. A similar fate met Maria Rider, sixty-seven, on the night of Thursday 19 January 1888, as she tried to cross the busy Borough end of Great Dover Street at the junction with Long Lane. She had made it to the middle of the road, near a traffic island equipped with a urinal, when a van being driven by one horse struck her at around 8mph. She was taken into a nearby shop by a passing ship’s steward and then to hospital where she died on 13 February from head injuries and a subsequent bacterial infection. The driver, Edward Dye, a biscuit dealer en route from London Bridge to the Swan pub 30 yards down the road, had the grace to instantly apologise when stopped by witnesses. He also appeared ‘perfectly sober’ and was driving on the correct side of the road. Dye was acquitted of manslaughter on the evidence that the victim had suddenly stepped into his path.

Children were just as vulnerable to death on the roads. David Cavalier was only a toddler, twenty-two months old, when he was run over in Bethnal Green, east London. It was 8.30 p.m. on Sunday 8 July and he was playing on the pavement outside his home in Warner Place. Further down the road two plain-clothes policemen were patrolling. There was no traffic and all seemed quiet until a horse and cart carrying a woman and child galloped round the corner from Old Bethnal Green Road at around 10mph. Eliza Cavalier, no doubt keeping one eye on her son and one eye on the housework, noticed the boy run into the road just as she heard the clatter of the approaching vehicle. ‘I ran into the road to protect him,’ she recalled. ‘My hand just touched his clothes when I was thrown away by the horse and knocked down and the cart went over me. I was so frightened.’ While Eliza suffered only minor injuries, the wheel of the cart had passed right over her son’s head, fracturing his skull, and he died not long after being taken to the Children’s Hospital in Hackney Road. According to newspaper reports the driver of the cart, fish porter Thomas Tarplett, twenty-five, had been drinking, although he was sober when taken down to the police station. A month later he was cleared of both manslaughter of the child and causing bodily injury to the mother, after witnesses testified that he was a ‘peaceable, steady and well-behaved young man’.24

The only case that resulted in a guilty verdict was that of Elizabeth Gibbs, who was run over on Tuesday 27 December 1887, but who died on 1 January, 1888. Perhaps the driver, Alfred Winwood, was convicted because of the status of his victim – the respectable wife of John Gibbs, a wealthy estate agent who had served as a land steward on the grounds of Bayfordbury Mansion in Hertfordshire, the seat of the wealthy merchants, the Baker family. But it was clear from the evidence that Winwood had also cut the corner of Halkin Street and Grosvenor Place, and was on the wrong side of the road. He also narrowly avoided killing John Gibbs and another pedestrian. As Mr Gibbs explained:

I was just a trifle in front of my wife, and immediately I [had] left the pavement and gone perhaps two or three steps, I suddenly became aware of a two-horse van coming down upon me, so close that I had neither time to think or act … I was knocked down towards the middle of the street … the moment I touched the ground I had presence of mind to swing myself round, and by that means I escaped the wheels.

He got up and found his wife lying in the road, her left arm crushed by the wheel.

When Winwood was flagged down by a postman who had witnessed the accident and told that he had run a woman over, he replied, ‘What the bloody hell has that got to do with me?’ and drove off. It appeared as if he had been drinking. Winwood was also late attending the inquest, and was arrested on a warrant issued by the coroner. He was forty-three, and employed by Messrs Batey’s Mineral Water and Ginger Beer Co. as a delivery driver for the Fulham district. At trial, his defence involved accusing John Gibbs and his wife of ‘contributory negligence’ by not taking more care crossing the road. His punishment for the crime of manslaughter was six months' hard labour, which in 1888 might still have involved ‘picking oakum’, a walk on the treadmill, lifting cannon balls, or sewing. It might have been a longer sentence had the jury not recommended him to the mercy of the court. After his release he returned home to his wife Sarah at a small house in Shoreditch they shared with a family of four, giving his occupation in the 1891 census as ‘traveller’.

As for John Gibbs, widowed so soon into the new year, he placed a death notice in The Times in tribute to his ‘dearly-loved wife’ and spent the rest of his life living with two of his daughters, first at Ebury Street in Belgravia and then in Hampstead. He died in 1905 at the age of eighty-five.25

One final case of interest did not involve horse-drawn transport but the bicycle. By the 1880s the awkward penny farthing had been refined to something similar to the modern bike, with lower seats and a chain connecting the pedals to the wheel. This new ‘safety bicycle’ would grow in popularity during the rest of the century, and there were cheers in the House of Commons in July 1888 when it was announced that bicycles and tricycles would be allowed on all roads in Hyde Park and St James’ Park. The design would be further improved with the pneumatic rubber tyre, invented by John Boyd Dunlop and patented in 1888. But, as with any method of transport, there would be reports of fatal accidents. One night in February that year a hotel landlord, forty-two-year-old John Watney Green, was knocked over by a cyclist in Kenley, Surrey, and died the next day – although the doctor suggested death was actually due to exhaustion and delirium tremens.26

Looking back from the twenty-first century it seems incredible that there was no real ambulance service in 1888. Dedicated horse-drawn carriages had been provided by the Metropolitan Board of Works for carrying fever and smallpox cases to hospital for twenty years, and it was possible to summon them by telegram for a small fee. The medical magazine The Lancet had recommended a centralised service in 1865 but the state of the nineteenth-century communication system (telegram, word of mouth and only a few primitive telephones) meant that it was quicker and easier to commandeer a carriage at the scene. The matter was left to local organisations like the Middlesex Hospital Board, who had a ‘chair and horse’ to transfer the injured from 1877, and the London Hospital who had one from 1881. The St John Ambulance provided carriages during the 1887 Jubilee celebrations, although early paramedics were often branded ‘body snatchers’. London would have to wait for the development of the motor engine before the first centralised ambulance service began in 1907.27

3

LIFE IN THE SUBURBS

The growth of transport both echoed and spurred on the growth of London itself. It was now expanding as fast as the suburban railway could lay down its tracks. More and more people were finding it convenient to commute to the City from what had once been open country. Areas like Leyton, Tottenham, West Ham, Southgate and Willesden doubled, tripled or even quadrupled in population between 1871 and 1891, as the middle class pursued respectability and the workers seized on the cheap fares to move out in search of a better quality of life. In 1888 young couples from the lower middle class were advised to choose houses ‘some little way out of London. Rents are less; smuts and blacks are conspicuous by their absence; a small garden, or even a tiny conservatory is not an impossibility’. Out in the suburbs there was fresh air, fewer shop windows to tempt the wife into extravagant spending, and less opportunity for the mother-in-law to interfere. The recommended areas were Sydenham, Forest Hill and Bromley in the south, and Finchley and Enfield in the north.28

Moving out of the city centre did not guarantee a peaceful existence, however. As the population expanded to the outer regions, so did the conflicts that decorate everyday life. While incidents were fewer, and less serious, murder still occasionally crept out to the suburbs.

South

Surbiton was only fifty years old, and a true creation of the railways (the station’s original name was ‘Kingston-on-Railway’). Although it did not become an urban district until 1894, it was a typical commuter town consisting of Victorian townhouses and churches on the dividing line between Greater London and the Surrey countryside. And while it was well within the boundary of the Metropolitan Police District’s V Division, it was an unlikely setting for a murder.

Seventy-one-year-old Major Thomas Hare had been living in a four-storey semi-detached house at No.13 St James Road for fourteen years following his retirement from the army. It was set away from the road and visitors had to climb the steps to knock on the door and await the attendance of the housemaid. The major, who had served in the 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot and the Cape Mounted Rifles in South Africa, had relatively few problems to occupy his twilight years other than the disability of his wife of nearly forty years, Frances. They owned another property in Surbiton Hill and were supported by their two youngest sons, both employed responsibly by the local council and a bank respectively. The oldest was serving with the army in India.29