Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

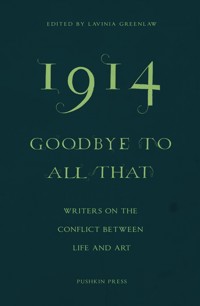

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A wide-ranging collection of reflective essays, to mark the centenary of the conflict that changed the world. In this collection of essays, ten leading writers from different countries consider the conflicts that have informed their own literary lives. 1914-Goodbye to All That borrows its title from Robert Graves's "bitter leave-taking of England" in which he writes not only of the First World War but the questions it raised: how to live, how to live with each other, and how to write. Interpreting this title as broadly and ambiguously as Graves intended, these essays mark the War's centenary by reinvigorating these questions. The book includes Elif Shafak on an inheritance of silence in Turkey, Ali Smith on lost voices in Scotland, Xiaolu Guo on the 100,000 Chinese sent to the Front, Daniel Kehlmann on hypnotism in Berlin, Colm Toibin on Lady Gregory losing her son fighting for Britain as she fought for an independent Ireland, Kamila Shamsie on reimagining Karachi, Erwin Mortier on occupied Belgium's legacy of shame, NoViolet Bulawayo on Zimbabwe and clarity, Ales Steger on resisting history in Slovenia, and Jeanette Winterson on what art is for. Contributors include: Ali Smith - Scotland Ales Steger - Slovenia Jeanette Winterson - England Elif Shafak - Turkey NoViolet Bulawayo - Zimbabwe Colm Toibin - Ireland Xiaolu Guo - China Erwin Mortier - Belgium Kamila Shamsie - Pakistan Daniel Kehlmann - Germany 'Tender, compassionate humanity' Peter Conrad, Observer 'A global gathering of essayists here reimagine the war from a variety of vantage points' Guardian 'This superb collection of essays by some of today's leading writers stands out among the many books commissioned to mark the centenary of the First World War.' The Lady Lavinia Greenlaw's poetry includes The Casual Perfect and A Double Sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde. Other works include The Importance of Music to Girls and Questions of Travel: William Morris in Iceland. She was the first artist-in-residence at the Science Museum, and received the Ted Hughes Award for her sound work Audio Obscura. Her work for BBC radio includes documentaries about Elizabeth Bishop, Emily Dickinson, the darkest place in England and Arctic light.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 172

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1914

GOODBYE TO ALL THAT

Writers on the Conflict between Life and Art

Edited by Lavinia Greenlaw

PUSHKIN PRESS LONDON

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

ONE OF MY grandfathers was old enough to fight in the First World War. Bill was the son of a Scottish railway clerk and the first of his family to go to university. He was at Aberdeen, reading Classics when, along with three of his four brothers, he enlisted with the Gordon Highlanders. One was killed, one lost a leg, one was made deaf and Bill had his lower lip shot off. Can you imagine a narrower escape?

On his return, Bill endured pioneering plastic surgery which involved flesh from his chest being grown from a flap of skin into a pedicle, which was attached to his mouth in order to regenerate it. He was one of only two in his class to survive the war, and both decided to become doctors, Bill undergoing the last of his surgery during the first year of his training. He died of pneumonia when my father, his youngest child, was eighteen months old. My father became a doctor, too.

The First World War changed the course of life. It also changed the course of lives to come. A hundred years on, it is still in sight but has slipped out of reach. The gap opening up between present and past is full of reverberations, something of which this collection of essays takes as its starting point. What does it mean to have your life and your identity as an artist shaped by conflict? I didn’t want writers simply to return to the past but to formulate and reinvigorate questions we should never stop exploring. They were asked to consider the loss of literary innocence or ideals, the discovery of new ones, the question of artistic freedom, and what it means to embrace new imperatives or to negotiate imposed expectations.

While we all know this conflict as a “world” war, few of us are aware of the true extent of global involvement that political repercussions, complex allegiances and colonial grip incurred. The countries listed as participants range from China to Liberia, Alaska to Romania. In order to reflect something of this, I decided to ask ten writers from different countries involved in the War to contribute. Each has their own experience to bring to bear of the tensions—fruitful or not—between life and art, and how these are amplified by all kinds of conflict.

I have borrowed the title, Goodbye to All That, from Robert Graves’s famously “bitter leave-taking of England”, in which he writes not only of the First World War but of the questions it raises: how to live, how to live with each other, and how to write.

LAVINIA GREENLAW

GOOD VOICE

Ali Smith

ALI SMITH was born in Inverness in 1962 and now lives in Cambridge. She is the author of Artful, There but for the, Free Love, Like, Hotel World, Other Stories and Other Stories, The Whole Story and Other Stories, The Accidental, Girl Meets Boy and The First Person and Other Stories. Her retelling of Sophocles’ Antigone is published by Pushkin Children’s Books.

THERE WAS A MAN who had two sons. And the younger of them said to his father, Father, give me the share of property that is coming to me.

Did you know about this? I say to my father. There was a German linguist who went round the prisoner-of-war camps in the First World War with a recording device, a big horn-like thing like on gramophones, making shellac recordings of all the British and Irish accents he could find.

Oh, the first war, my father says. Well, I wasn’t born.

I know, I say. He interviewed hundreds of men, and what he’d do is, he’d ask them all to read a short passage from the Bible or say a couple of sentences or sing a song.

My father starts singing when he hears the word song. Oh play to me Gypsy. That sweet serenade.

He sings the first bit in a low voice then the next bit in a high voice. In both he’s wildly out of tune.

Listen, I say. He made recordings that are incredibly important now, because so many of the accents the men speak in have completely disappeared. Sometimes an accent would be significantly different, across even as little as the couple of miles between two places. And so many of those dialects have just gone. Died out.

Well girl that’s life in’t it? my father says.

He says it in his northern English accent still even though he himself is dead; I should make it clear here that my father’s been dead for five years. We don’t tend to talk much (not nearly as much as I do with my mother, who’s been dead for nearly twenty-five years). I think this might be because my father, in his eighties when he went, left the world very cleanly, like a man who goes out one summer morning in just his shirtsleeves knowing he won’t be needing a jacket that day.

I open my computer and get the page up where, if you click on the links, you can hear some of these recorded men. I play a couple of the Prodigal Son readings, the Aberdonian man and the man from somewhere in Yorkshire. The air round them cracks and hisses as loud as the dead men’s voices, as if it’s speaking too.

So I want to write this piece about the first war, I tell my father.

Silence.

And I want it to be about voice, not image, because everything’s image these days and I have a feeling we’re getting farther and farther away from human voices, and I was quite interested in maybe doing something about those recordings. But it looks like I can’t find out much else about them unless I go to the British Library, I say.

Silence (because he thinks I’m being lazy, I can tell, and because he thinks what I’m about to do next is really lazy too).

I do it anyway. I type the words First World War into an online search and go to Images, to see what comes up at random.

Austrians_executing_Serbs_1917.JPG.

Description:

English: World War 1 execution squad.

Original caption: “Austria’s Atrocities. Blindfolded and in a kneeling position, patriotic Jugo-Slavs in Serbia near the Austrian lines were arranged in a semicircle and ruthlessly shot at a command.”

Photo by Underwood and Underwood. (War Dept.)EXACT DATE SHOT UNKNOWN NARA FILE: 165-WW-179A-8 WAR & CONFLICT BOOK NO. 691 (Released to Public).

There’s a row of uniformed men standing in a kind of choreographed curve, a bit like a curve of dancers in a Busby Berkeley. They’re holding their rifles three feet, maybe less, away from another curved row of men facing them, kneeling, blindfolded, white things over their eyes, their arms bound behind their backs. The odd thing is, the men with the rifles are all standing between two railway tracks, which curve as well, and they stretch away out of the picture, men and rails, like it could be for miles.

It resembles the famous Goya picture. But it also looks modern, because of the tracks.

There’s a white cloud of dust near the centre of the photo because some of these kneeling men are actually in the process of being shot as the photo’s being taken (EXACT DATE SHOT). And then there are the pointed spikes hammered in the ground in front of every one of the kneeling prisoners. So that when you topple the spike will go through you too. In case you’re not dead enough after the bullet.

Was never a one for musicals, me, my father says.

What? I say.

Never did like, ah, what’s his name, either. Weaselly little man.

Astaire, I say.

Aye, him, he says.

You’re completely wrong, I say. Fred Astaire was a superb dancer. (This is an argument we’ve had many times.) One of the best dancers of the twentieth century.

My father ignores me and starts singing about caravans and gypsies again. I’ll be your vagabond, he sings. Just for tonight.

I look at the line of men with the rifles aimed. It’s just another random image. I’m looking at it and I’m feeling nothing. If I look at it much longer something in my brain will close over and may never open again.

Anyway, you know all about it already. You don’t need me. You did it years ago, my father says, at the high school.

Did what? I say.

First World War, he says.

So I did, I say. I’d forgotten.

Do you remember the nightmares you had? he says.

No, I say.

With the giant man made of mud in them, the man much bigger than the earth?

No, I say.

It’s when you were anti-nuclear, he says. Remember? There was all the nuclear stuff leaking onto the beach in Caithness. Oh, you were very up in arms. And you were doing the war, same time.

I don’t. I don’t remember that at all.

What I remember is that we were taught history by a small, sharp man who was really clever, we knew he’d got a first at university, and he kept making a joke none of us understood, Lloyd George knew my father he kept saying, and we all laughed when he did, though we’d no idea why. That year was First World War, Irish Famine and Russian Revolution; next year was Irish Home Rule and Italian and German Unifications, and the books we studied were full of grainy photographs of piles of corpses whatever the subject.

One day a small girl came in and gave Mr MacDonald a slip of paper saying, Please, sir, she’s wanted at the office, and he announced to the class the name of one of our classmates: Carolyn Stead. We all looked at each other and the whisper went round the class: Carolyn’s dead! Carolyn’s dead!

Ha ha! my father says.

We thought we were hilarious, with our books open at pages like the one with the mustachioed men, black as miners, sitting relaxing in their open-necked uniforms round the cooking pot in the mud that glistened in huge petrified sea waves over their heads. Mr MacDonald had been telling us about how men would be having their soup or stew and would dip the serving spoon in, and out would come a horse hoof or a boot with a foot still in it.

We learnt about the arms race. We learnt about Dreadnoughts.

Meanwhile, some German exchange students came, from a girls’ school in Augsburg.

Oh they were right nice girls, the German girls, my father says.

I remember not liking my exchange student at all. She had a coat made of rabbit hair that moulted over everything it touched, and a habit of picking her nose. But I don’t tell him that. I tell him, instead, something I was too ashamed to say to him or my mother out loud at the time, about how one of the nights we were walking home from school with our exchange partners a bunch of boys followed us shouting the word Nazi and doing Hitler salutes. The Augsburg girls were nonplussed. They were all in terrible shock anyway, because the TV series called Holocaust had aired in Germany for the first time just before they came. I remember them trying to talk about it. All they could do was open their mouths and their eyes wide and shake their heads.

My father’d been in that war, in the Navy. He never spoke about it either, though sometimes he still had nightmares. Leave your father, he had a bad night, our mother would say (she’d been in it too, joined the WAF in 1945 as soon as she was old enough). My brothers and sisters and I knew that his own father had been in the First World War, had been gassed, had survived, had come back ill and had died young, which was why our father had had to leave school at thirteen.

He was a nice man, poor man, he said once when I asked him about his father. He wasn’t well. His lungs were bad. When he died himself, in 2009, my brother unearthed a lot of old photographs in his house. One is of thirty men all standing, sitting and lying on patchy grass round a set of First World War tents. Some are in dark uniform, the others are in thick white trousers and jackets and one man’s got a Red Cross badge on both his arms. They’re all arranged round a sign saying SHAVING AND CUTTING TENT, next to a man in a chair, his head tipped back and his chin covered in foam. There’s a list of names on the back. The man on the grass third from the left must be my grandfather.

We’d never even seen a picture of him till then. One day, in the 1950s, after my parents had been married for several years, a stranger knocked at the door and my mother opened it and the stranger said my father’s name and asked did he live here and my mother said yes, and the stranger said, who are you, and my mother said, I’m his wife, who’re you? and the stranger said, pleased to meet you, I’m his brother. My father said almost nothing when it came to the past. My mother the same. The past was past. After my mother died, and when the Second World War was on TV all the time in anniversary after anniversary (fifty years since the start, fifty years since the end, sixty years since the start, sixty years since the end), he began to tell us one or two things that had happened to him, like about the men who were parachuted in for the invasion of Sicily (my father was an electrician on one of the warships going towards Italy) but by mistake were dropped too far out from land so the sea was full of them, their heads in the water and the ships couldn’t stop, you couldn’t just stop a warship, we waved to them, we called down to them, we told them we’d be back for them, but we knew we wouldn’t and so did they.

Now I tell my father, who’s five years dead, you know, I wrote to the Imperial War Museum recently about that old picture with your dad in it, and I asked them whether the white clothes he’s wearing meant anything special, a hospital worker or something, and a man wrote back and told me maybe your dad was an Army baker but that to know for sure we’d need Service records and that the problem with that is that sixty per cent of First World War Army records were burnt and lost in a German raid in 1940.

Things get lost all the time, girl, he says.

Do you know if he was a baker, maybe? I say.

Silence.

My grandfather doesn’t look much like my father in the picture, but he looks very like one of my brothers. I’ve no idea what he saw in his war. God knows. There’s no way of knowing. I’ll never know what his voice sounded like. I suppose it must have sounded a bit like my father’s. I suppose his voice was in my father’s head much like my father’s is in mine. I wonder if he could sing.

Red sails in the sunset, my father sings right now, out of tune (or maybe to his own tune). Way out on the sea.

Gas!—GAS!—quick, boys! That was the Wilfred Owen poem. In it, gas was written first in small letters then in capitals, which, when I was at school, I’d thought very clever, because of the way the realization that the gas was coming, or the shouts about it got louder the nearer it came.

Oh carry my loved one. Home safely to me.

And Owen had convalesced, and met his friend Siegfried Sassoon, and learnt to write a whole other kind of poetry from his early, rather purple sonnets, at Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh, which was close to home, even though Edinburgh was itself a far country to me, at fifteen, in Inverness, when I first read Owen.

He sailed at the dawning. All day I’ve been blue.

My father’s voice is incredibly loud, so loud that I’m finding it hard to think anything about anything. I try to concentrate. There was a thing I read recently, a tiny paragraph in the International New York Times, about a rare kind of fungus found nowhere else in the UK, but discovered growing in the grounds of Craiglockhart and believed by experts to have been brought there from mainland Europe on the boots of the convalescing soldiers. Microscopic spores on those boots, and weeks, months, years later—the life.

But I can’t even think about that because:

Red sails in the sunset. I’m trusting in you.

Okay.

I sing back, quite loud too, a song of my own choice.

War is stupid. And people are stupid.

Don’t think much of your words, my father says. Or your tune. That’s not a song. Who in God’s name sang that?

Boy George, I say. Culture Club.

Boy George. God help us, my father says.

The 1984 version of Wilfred Owen, I say.

Hardly, he says. Boy George never saw a war. Christ. What a war would’ve done to him.

Wilfred Owen was gay too, you know, I say. I say it because I know it will annoy him. But he doesn’t take the bait. Instead:

People aren’t stupid. It’s that song that’s stupid, he says.

It’s not a stupid song, I say.

You got that Wilfred Owen book as a school prize, he says.

Oh yes, so I did, I say.

You chose it yourself at Melvens, he says. First prize for German. 1978.

How do you even remember all this stuff? I say. And really. What does it matter what prize I ever got for anything?

You were good at German, he says. Should’ve kept on with your languages. Should’ve learnt them all while you had the chance, girl. You still could. I wish I’d had the chance. You listening to me?

No.

No, cause you never listen, he says. And you were learning Greek last year—

How do you even know that? You’re supposed to be dead, I say.

—and gave it up, didn’t you? he says. As soon as it got too difficult.

The past and the future were hard, I say.

Start it again, he says in my ear.

Can’t afford it, I say.

Yes you can, he says. It’s worth it. And you don’t know the first thing about what it means not to be able to afford something.

I’m too old, I say.

Learn anything, any age, he says. Don’t be stupid. Don’t waste it.

While I’m trying to think of other songs I can sing so I don’t have to listen to him (Broken English? Marianne Faithfull? It’s just an old war. It’s not my reality)—

Here, lass, he says. Culture Club!

What about them? I say.

That fungus! In that hospital, he says. Ha ha!

Oh—ha! I say.

And you could write your war thing, he says, couldn’t you, about when you were the voice captain.

When I was the what? I say.

And you had to lay the wreath at the Memorial. With that boy who was the piper at your school. The voice captain for the boys. Lived out at Kiltarlity. His dad was the policeman.

Oh, vice-captain, I say.

Aye, well. Vice, voice. You got to be it and that’s the whole point, he says. Isn’t it? Write about that.

No, I say.

Well don’t then, he says.

It was a bitter-cold Sunday, wet and misty, dismal, dreich, everything as dripping and grey as only Inverness in November can be; we stood at the Memorial by the river in our uniforms with the Provost and his wife and some people from the council and the British Legion, and we each stepped forward in turn below all the names carved on it to do this thing, the weight of which, the meaning and resonance of which I didn’t really understand, though I’d thought I knew all about war and the wars, until I got home after it and my parents sat me down in the warm back room with a kindness that was quiet and serious, made me a mug of hot chocolate then sat with me in a silence, not companionable, more mindful than that, assiduous.

Damn. Look at that. I just wrote about it even though I was trying not to.

Silence,

silence,

silence.

Good.

It’s a relief.

That image of the soldiers on the railway tracks is still on the screen of my computer.