Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

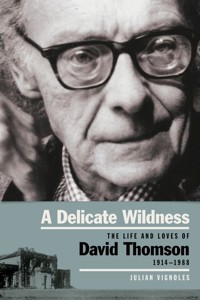

David Thompson was a Scottish writer, folklorist and radio producer, who became an honorary Irishman. His life took a defining turn when as a student of history at Oxford, he came to County Roscommon in the early 1930's as tutor to an Anglo-Irish family, the Kirkwoods. He fell in love with his charge, Phoebe, the daughter of the house, and returned to London in 1939, becoming a radio producer with the BBC, where he spent the remainder of his working days. David Thomson was affecting, febrile and uniquely talented. His life was dominated by his love of women and locale – Ireland, Scotland, London – sensuous worlds apprehended through the artistry of his written legacy. With over fifty unseen photographs, this biography speaks to the writer's 'delicate wildness' (Seamus Heaney's phrase) and to the contradictions and passions of a singular man.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 308

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

the lilliput press

dublin

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Nairn in Darkness

2. Woodbrook: Enchantment in Roscommon

3. A BBC Producer

4. The Kiernan Sisters

5. Martina

6. Challenges at the BBC

7. Moral Candour, Fiction and ‘Fiction’

8. Seal and Hare Uncovered

9. Man and Fox

10. The Memoir Triumphant

11. Phoebe

12. The Woodbrook Legacy

13. The Great Hunger

14. In Camden Town

15. County Clare Interlude

16. A Roscommon Coda

17. Nairn in Light

Postscript

To Peter and Anne, myparents

Acknowledgments

This book is based on David Thomson’s writings, notebooks and correspondence, and on the recollections of family and friends. All his published works have an autobiographical element, so I have made much reference to them throughout. He also had a great archival sense throughout his life, keeping large amounts of notes and letters.

There were many people who encouraged and helped with this project and to whom I’m grateful. I had very valuable guidance at crucial stages of the work from Tim Lehane; Joe Duffy gave me great advice on draft chapters; Timothy, Luke and Ben Thomson were supportive and candid in recollection of their parents; Sally Harrower and her colleagues at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, afforded me a most pleasant time, as did the Rathmines Library in Dublin. Angela Bourke shared Thomson insights. Seán and Desmond Biddulph and Steve Bober were invaluable because of interest in their own family histories. I’m grateful to Joe Mulholland and RTÉ Archives for the interview he recorded with David Thomson in 1987.

I’ve shared a love for all matters Woodbrook with my friends, the owners of Woodbrook House since 1970, Mai and the late John A. Malone, who always celebrated their home’s literary heritage and had a great welcome, allowing me to photograph the house and grounds. Others helped along the way: Kate Kavanagh, Luke Dodd, May Moran, Marion Dolan, David Gillespie, Lionel Gallagher, Mary O’Rourke (née Pogue), Percy Carty, Neil Belton, Stina Greaker, Ríonach Uí Ógáin, Evelyn Conlon, Dave McHugh, Norman Colin, Judy Cameron, Melanie and Patrick Cuming, David and Sue Gentleman, Christopher Ashe, Cathal Goan, Bairbre Ní Fhloinn, Diane Barker, Patrick Kinsella and Jeananne Crowley. Tim Dee was an incisive guide to BBC matters and on David’s legacy. Marie, Michael, Christopher and Catherine Heaney and Faber and Faber Ltd kindly gave permission to quote from Seamus Heaney’s work.

My wife, Carol, and sons Eoghan and Rory, encouraged me from the start. Antony Farrell of The Lilliput Press was enthusiastic when I approached him about telling the Thomson story, and both he and Fiona Dunne proved exacting editors.

This book would not have been possible without the support and generosity of the late Martina Thomson, who talked to me at length, even as her health began to fail. I had phoned her from the famous Henry’s pub in Cootehall in May 2013 during that year’s John McGahern Seminar, in which David’s twenty-fifth anniversary was marked. I asked what she would think about my writing his biography. Her response was positive and the journey began.

Introduction

On the evening of 26 February 1989, a group of distinguished Irish people gathered in The Royal Irish Academy in Dublin for a commemoration. They were to honour not a fellow Irish person, but a Scotsman, born in India. It was one year after his death. He was David Thomson – writer, folklorist, radio producer, scholar and honorary Irishman. He suffered sometimes-frail health and poor eyesight, but had a mind quietly on overdrive for most of his life.

Seamus Heaney began proceedings that night: ‘This is a wake of sorts, where we remember the care, delicacy, research and affection that David invested in this country – as a historian, a folklorist and as a person. He had made intimates of his readers.’

Jim Delaney of University College, Dublin, paid tribute to Thomson as a folklore collector and co-author of The Leaping Hare. ‘He was scholarly and not just a folklorist, but a literary artist’ he said. The poet Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill said that in The People of the Sea Thomson had carried with him what she described as ‘the mind-set of the Irish language so totally’, though he never learnt the language and was apologetic for that.

The broadcaster Seán Mac Réamoinn said of Thomson’s most famous work, Woodbrook: ‘I know of no book that explains us better to the world outside. And does so with such unsentimental sympathy.’ He continued: ‘That seemingly remote and withdrawn man had this vivid and acute knowledge of people and things and what people were doing, what things were significant in the world. He was his own man, but he was also ourman.’

John McGahern also recalled Woodbrook: ‘It is strange in the English tradition of writing about Ireland. I know of no voice like it; there is no savage indignation, no exasperated tolerance, no dehumanizing farce, and no superior tone. It has a rare sweetness and gentleness.’

I first came across David Thomson when browsing in Fred Hanna’s Dublin bookshop during the summer of 1985. I saw the hardback edition of Woodbrook in a remainder sale. The jacket photo was an atmospheric shot of water and reeds. Something struck me about it and I bought it. It changed my life. And so devastated was I with the ending, that I immediately read the whole book again.

I was working in RTÉ Radio, so I responded by making a documentary to express my admiration for the book. The programme, ‘The Story of Woodbrook’, was a labour of love. When, about a year later, I got to meet David himself, I was face to face with a hero, a Dylanesque figure, who engrossed me in a way no one had ever done.

This book is the first to tell the David Thomson story; the complexity of one gifted man’s life; the trials and triumphs of his interaction with the world; his wit and wisdom; his take on love and loss – and his frailties. It’s an account of his journey as a writer and an appraisal of the work he left us. Perhaps most of all it’s a story about the people he loved and the people who loved him.

David Thomson’s legacy of thirteen published works were developed out of the notebooks, the ones that usually filled his jacket pockets, containing thoughts, reflections, sometimes inspired ramblings. These were compiled in the corridors of the BBC, in pubs, on park benches in North London, in the company of literati and the homeless.

In relation to Ireland, he illuminated the role of folk memory in our understanding the past. He shone a light on our history and was an important chronicler of the fortunes of the Anglo-Irish community in the mid twentieth century.

And what of David Thomson, the man? He came from a family that flew a flag when they were in residence, where as a visitor after Newton house in Nairn had been converted to a hotel, he was refused entry because of his appearance. Once, a child on a London street insisted that David take a sixpence the boy was offering him. He was an Oxford graduate who became an Irish farmer. He once had a love affair with a woman who worked in an African brothel. He liked having a drink with homeless people in London. His greatest work concerns a love story with a girl who was only twelve, but who haunted him romantically and creatively. He liked to brush against women’s hair on buses. He wrote a heartfelt letter to Harold Wilson protesting about the Vietnam War. He identified horses by their names in photographs. He admitted that animals sexually aroused him. He once wrote an angry letter to complain about a ban on men shaving in the borough of Camden’s public toilets. His death in 1988 caused his wife an extended period of profound grief.

In his published work and in his notebooks, Thomson not only shows literary prowess but reveals himself openly and frankly to his readers. His writing enriches us with curiosity about many aspects of humanity – tradition, belief, memory and love. His writing expresses one man’s yearning for contentment as he deals imaginatively and articulately with the urges and passions that drive all of us. He was flirtatious, bold, playful, bohemian, and eccentric, with ‘the manners of a king, the gentleness of a saint’, according to one of his sons. Seamus Heaney summed up his spirit when he said David had ‘a delicate wildness’.

In May 2013 I was involved with John Kenny of University College Galway and Philip Delamere, County Leitrim’s arts officer, in organizing a tribute to David Thomson on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death, as part of the John McGahern International Seminar. Woodbrook admirers emerged, many with their well-worn original editions, their enthusiasm palpable.

I travelled to Nairn in the Scottish Highlands, by train as he had done many times, to visit his childhood home. I saw the fisher town that he described – now with no fishing vessels to be seen, but pleasure yachts bobbing in the breeze. I crossed the bridge over the Nairn River, where his ashes had been scattered, to a the beach where British troops prepared for the Normandy landings as David began his career at the BBC. At Newton, the family seat to which David Thomson felt mixed allegiances, a gardener worked in the grounds overlooking the Firth of Moray; looking up at the bare flagpole that once used to announce the family’s presence, he remarked that their era was well and truly gone now. But the change that concerned him more was climatic, as the flower bulbs he was planting might be ‘fooled’ by the mild winter days and sprout but are killed by spring frost. David Thomson loved flowers and would have approved of this concern.

One day last winter, as I drove slowly down the lane that was once the Woodbrook avenue, towards the house and past the places he described so beautifully, the memory of Thomson’s words, written about this corner of Ireland so long ago, came dramatically to light.

I realized again why I wanted to write a book about him.

David, aged ten, with pets including Kuti the dog, at Pattison Road, Hampstead, May 1924.

The Spring

In memoriam David Thomson

Choose one set of tracks and track a hare

Until the prints stop, just like that, in snow.

End of line. Smooth drifts. Where did he go?

Back on her tracks, of course, and took a spring

Yards off to the side; clean break; no scent or sign.

She landed in her form and then ate snow.

(Which is why Pliny thought the fur goes white

And why one friend imagined the Holy Ghost

As a great white hare on the summit of a ridge –

Then sprung himself at last, still weaving, dodging,

Haring it out until the very end,

The shake-the-heart, the dew-hammer, the far-eyed.)

—Seamus Heaney

Martina Thomson’s Diary

12 October 1988 Nairn

The river was fast and brown with choppy waves. I tore the seal off the plastic bag. There was the stuff. It was not so soft as I had imagined it, but hard like little gravel. I took a handful of ashes and put it in my hair. Then I took the bag to the edge of the river and strewed the remainder into the fast flowing water. It left a white trail, which travelled at great speed down the river. I rubbed the ashes into my hair, I felt you could spare that bit.

By the time I was back to the hotel bedroom I thought of those ashes as mingling with the open sea of the Moray Firth.

1. Nairn in Darkness

‘All the Irish should be hanged!’ said Granny in a louder voice than usual. She was known to everyone as kind and gentle.

This fragment of a breakfast-table conversation, recounted inNairn in Darkness and Light, echoed through David Thomson’s life, and with it the fraught relationship between the two islands. He remembered it as a seven-year-old from a morning when his household in Nairn was discussing the impending arrival of David Lloyd George, the British prime minister, to holiday in the Highlands that summer of 1921.

But David’s grandmother was asked to clarify her remark; did she mean to include the family’s local acquaintances in Nairn, the O’Toole’s? That family was related to Saint Laurence O’Toole, the twelfth-century Abbot of Glendalough and Archbishop of Dublin, some of whose descendants in this part of Scotland had decided, in order to disguise their Irish background, to change their name to Hall, after Ireland’s Easter Rebellion of 1916. Granma stood firm.

Far away from this town in the north-east of Scotland David Thomson’s life had begun, five thousand feet above sea level, in the city of Quetta, then part of British-occupied India. His father, Alexander Guthrie Thomson, a Scottish native born in 1873, had obtained his commission into the Indian army as a 2nd lieutenant in 1893. His posting was with the 5th Regiment of Punjab Infantry founded in 1849. The regiment later became part of the army of the new state of West Pakistan in 1947, and Quetta, close to the Afghan border, is now part of the Punjab region of Pakistan. The two Pakistan states were created, controversially, as part of the Indian independence settlement in 1947, in the two regions of India that had Muslim majorities.

The Indian army had been established for the colonial purpose of subduing a subcontinent, controlling its warring factions and maintaining it as part of the British empire. There were different wars during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; uprisings by Sikhs and Muslims, then the Mutiny of 1858, which nearly ended British rule. The Indian army’s rank and file largely consisted of Indian men, as Britain and Ireland alone could not have supplied the army manpower needed for a country of India’s size. At the time Alec Thomson got his commission in 1893, the ratio of Indian to British servicemen was two to one.

When Thomson had graduated from Sandhurst, he ironically couldn’t afford to remain in the British army itself. Officers at that time needed a separate income if they were to live the ‘appropriate’ life, to be ‘like well-off gentlemen’. For the privilege of being officers, the men had to buy their own uniforms, day-to-day and ornate ceremonial ones, as well as swords for battle and state occasions. The Thomsons were well-to-do, but the Finlays, the family he would marry into, were in a different league financially and in terms of connections. Why there was no ‘dig out’ by the wealthier side of the family at the Newton estate in Nairn for the young Thomson is unclear. But India was perhaps attractive on its own merits. The Indian army, which was usually short of officers, provided everything free. Also, in India, infantry officers were mounted, and that appealed to Alec Thomson. India was an adventure for men like him. The polo was apparently better, too.

The Indian army maintained British power in the subcontinent by at times benign, but mostly firm and sometimes brutal means. It carried out a notorious massacre in April 1919 at Jallianwala Bagh, in the city of Amritsar, opening fire on a crowd protesting at the arrest of local leaders. Exact figures for casualties are disputed but hundreds of peaceful protestors, including children, were mown down. Ninety-four years later, in 2013, David Cameron became the first British prime minister to visit the site and offer apologies, describing it as a ‘deeply shameful event in British history’.

As the young Alec Thomson began his military career stationed in British Baluchistan, where Quetta is located, he was thinking of someone back home in Scotland. Before he’d left, Thomson had fallen in love with Annie Finlay, his first cousin, when she was aged just fifteen. She was born in 1880. When they became engaged during one of his home leaves, her family, on both sides, disapproved. The Episcopal Church of Scotland had only just changed its rules to allow marriage between cousins.

Annie Finlay managed to follow her fiancé to India, chaperoned by her aunt May, whose husband was in the Indian Civil Service. She married Alexander Thomson on Christmas Eve, 1907. The newly-wed Annie was to move from her native Scottish Highlands to a very different and exotic mountainous region of the world.

A contemporary account describes one aspect of life for women in the Raj, as British-administered India was known.

The honey smell of the fuzz-buzz flowers, of thorn trees in the sun, and the smell of open drains and urine, of coconut oil on shining black human hair, of mustard cooking oil and the blue smoke from cow dung used as fuel; it was a smell redolent of the sun, more alive and vivid than anything in the West.1

In the late nineteenth century, thousands of young men left Britain for India to serve as administrators, soldiers and businessmen. Many young women followed in search of marriage – and even love. These young women were known as ‘The Fishing Fleet’. They endured discomforts and monotony, but also found an intoxicating environment, the sky aflame with vivid colours, pungent scents from, to them, exotic shrubs and flowers.

The Indian sub-continent Alexander Thomson and his family were to leave behind in 1914 was about to experience a great upheaval. In 1915, one of that country’s great sons, Mahatma Ghandi, returned from Europe to his enormous native country to champion the Indian masses and begin his unique independence struggle, based on civil disobedience.

David Thomson’s sisters, Mary and Joan, were born into this colonial environment in 1908 and 1911. Their only brother, David Robert Alexander, to give David his full name, was born on 17 February 1914. A third daughter, Barbara, was born later in Surrey and a fifth child, Lily, died in infancy in England. Stephen Bober, David’s sister Barbara’s son and David’s nephew, recalls his mother speaking of her father as a kind and just man, driven by the best sort of Christian values.

Alexander Thomson’s regiment, the 58th Vaughan Rifles, was active in France during World War I. He was decorated with several medals – some for service in particular campaigns, but he also received a Distinguished Service Medal and the French Croix-de-Guerre. Philip Mason in his book on the Indian army, writes of gallantry and devotion to duty, and at one point refers to ‘clearing a German trench’ to describe a much more brutal activity, almost casually describing the loss of life involved. He recounts a particular engagement involving Thomson’s battalion. Sir Arthur Wauchope of the Black Watch saw his regiment’s flank exposed, but the 58th came to their aid: ‘And a fine sight it was to see the 58th pushing forward, driving all before them. A year’s experience has taught our men that there was no regiment that ever served in the brigade they would as soon have as the 58th to come to their aid.’2

Alexander Thomson was seriously wounded at Rue-du-Bois on 9 May 1915. He was mentioned in dispatches on 31 May 1915, ‘for gallant and distinguished services in the field’. He returned to England where he lay for weeks, his body mutilated, in a darkened room, as his wife nursed him, between May and September 1915. He recovered and returned to the army, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in October 1919. He retired in May 1920. The family then lived mostly in Buxton, Derbyshire, and he ‘commuted’ by train for years to Manchester to different jobs. One of these was managing a factory, which employed disabled soldiers. Later he became secretary of the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust. This was a far-sighted early-twentieth-century progressive town-planning project to create a model community in this part of north London, with people of all classes living together in ‘beautiful houses set in a verdant landscape’. By 1935 the Suburb comprised a large swath of about 800 acres stretching from Golders Green in the south to East Finchley in the north.

In the winter of 1914, David’s mother left India with her two daughters and her nine-month-old son. It was a long voyage on a troop ship bound for France. Since secrecy prevailed after war was declared in August that year, his mother had no idea where her husband had been ordered to go, except that it was to the front. Alexander Thomson, not yet thirty, acting undoubtedly with personal bravery, carried out his duty, which involved willingly ordering other young men to almost certain death, as his wife nursed their only son, an infant who in time would quietly reject all of his father’s military values.

Annie Thomson brought the baby David and his sisters to her mother’s house, Tigh-na-Rosan, in the town of Nairn, the home of David’s Granma – she of the ‘hanging’ remark. A short walk away was Newton, the large family seat owned by Annie’s brother, Robert Bannatyne Finlay. The house was later converted to a hotel, and frequented by, among others, Charlie Chaplin, who holidayed there several times in his later years during the 1970s. Robert Bannatyne Finlay, later Viscount Finlay, had bought the house in 1887 during the first period he was MP for the area, the Inverness Burghs, between 1885 and 1892. The hotel still has Finlay and Chaplin suites.

David’s maternal Granma’s home, Tigh-na-Rosan in Nairn, as it is today.

Newton House, Nairn, in the Scottish Highlands, David’s uncle Robert Finlay’s family seat, now a hotel.

For the young David Thomson, his maternal grandmother’s house and his uncle’s mansion in Nairn, on the Moray Firth north-east of Inverness, became his most formative home as he began a lifelong relationship with that town, its history and traditions. In Nairn in Darkness and Light (published in 1987, a year before his death), he returned to the place of his childhood in this last published work. It’s an example of the Thomson blend of autobiography, memoir and evocation of place, in this case the world seen through a child’s eye via the prism of the seventy-two-year-old writer. The book earned him The McVitie’s Prize of Scottish Writer of the Year in 1987.

In Nairn in Darkness and Light’s opening chapter he continues to evoke that summer of 1921 and Lloyd George’s visit. At Newton disapproval is expressed at the Prime Minister’s apparent intention to reach a treaty with Ireland, giving it a degree of independence. The treaty negotiations, which were to have long lasting consequences for both islands, had begun in London that summer. The household in this privileged part of Nairn had its own local preoccupations, as David recalls a little sarcastically: ‘At breakfast and in the conservatory and billiard room the men were usually talking and laughing. Was the wind too strong, would the grouse fly high? Was the sun too bright for fish to rise, had the rain made the golf course greens too soft and slow, the tennis courts too quaggy?’

It could be said there was anti-Home Rule form in the house: Robert Finlay had under William Gladstone’s influence initially supported Home Rule for Ireland, before ‘turning coat’ on that issue and leaving Gladstone’s Liberal Party. He had now risen to the inner circle in the government of Lloyd George. Between 1916 and 1919, Finlay was Lord Chancellor in Lloyd George’s coalition government, then replaced by Lord Birkenhead, who was later a negotiator and a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In 1921, Uncle Robert, as David Thomson refers to him, was appointed to the Permanent Court of International Justice, established by the newly formed League of Nations, and which became the International Court of Justice in 1946.

That summer Robert Finlay and the family were shocked by the idea that Éamon de Valera might succeed in detaching Ireland from the British Empire to form a republic that would include its Protestant minority, who were hostile to the idea. This Protestant minority and their declining fortunes would later be a crucial experience in David Thomson’s life and part of the inspiration for Woodbrook.

When Lloyd George went fishing that autumn not far from Nairn, he not only offended the unionist consensus, but committed a fishing no-no; while others in his party were using flies – unsuccessfully – on the Kerry River, the Welshman slipped away downstream and apparently attached a worm to his line and landed a twenty-ounce brown trout, the only catch of the day, ‘Thereby adding to his sins in all the eyes of Newton, where fishing with a worm was taboo.’

Thomson’s evocation of that time ends as he notes that a letter arrived to interrupt the British leader’s holiday, from de Valera in Dublin, and Lloyd George had to convene a Cabinet meeting in nearby Inverness.

David said in 1987 that he began to write, ‘as soon as he could read and write’. At the age of seven he won a literary prize, that same year, 1921, in a magazine called ‘Little Folks’. The prize was a modest one: a framed photograph of Derwent Water in the Lake District. He recalled taking the bus to the nearest town to their home in Buxton, Derbyshire, to collect his prize. He was dying to show his trophy to his sisters, but sat on it by mistake on the bus home and the glass splintered on the picture, so that was what his siblings saw. The story itself was about flower show daffodils that go missing from his uncle’s garden, and a boy and his brother’s attempts to retrieve them.

Nairn in Darkness and Light opens with a letter from David to Kolya Yakovlevich, a childhood friend who like David, spent summers in Nairn. Kolya had a Ukrainian father but his mother Catriona was Scottish, a Ferguson. She had met Ivan Yakovlevich while they were both studying medicine in Edinburgh University. They fell in love, got married and went to live in Kiev. Things didn’t work out though David never found out why, but Catriona returned to Scotland with Kolya, or Kolly, as he became known. He was regarded as a delinquent, a little mad and engaged in shoplifting, but David admired him, it would seem, for this ‘whiff of sulphur’ about him, not to mention his good looks and natural charm. David’s grandmother thought the child should have been sent to Borstal, after a particular incident where he damaged the roof of her house, and rain caused a ceiling to collapse, wrecking of a valuable Persian inlaid escritoire.

David saw Kolya every summer till he was seventeen, their mothers being tennis partners. It was on long cycling excursions with the Ukrainian–Scottish lad that Thomson’s lifelong love of the countryside first developed. Their letter-writing forms one of the threads of Nairn in Darkness and Light. He refers to Kolya as his cousin, but says he was never sure whether he was a real cousin or not, leaving a riddle that might possibly have involved a transgression by a member of the family at some stage.

There are strong hints in the young Thomson’s letter writing to Kolya of his future talent. In one, he’s describing morning prayers in Newton and regretting that his friend wasn’t there to enjoy this scene with him:

I was kneeling beside uncle Tom and you would have been beside me and he was muttering his usual cross things all through the beginning and if they hear they take no notice but today they did because when uncle Robert got to the Lord’s Prayer uncle Tom said, ‘No Popery’ quite out loud, and some of the new maids giggled. Cathy and Gina I guess, and Uncle Robert stopped and Mrs Waddell marched the maids out of the dining room but it should have been Uncle Tom who was marched out.

Thomson later admits embellishing this ‘No Popery’ scene, but of course he was recognizing the value of doing that. He then sums up the climate in Nairn and evokes a memory many from these latitudes would share:

It often rained in Nairn for days and days, but I think most people’s memories of childhood summers live in blue skies, white clouds, the dust of the roads, the earthquake cracks in sun baked pathways, the blue and white sea, green leaves and grass, hot pebbles and the yellowy whites of the sea sand. Mine certainly does.

David aged nine, with his parents, sister Barbara and Granma, at Newton, August 1923.

David had a morbid curiosity, aroused by one of the employees, the henwife at Newton, as she went about her work. The birds’ feeding time first attracted this curiosity, and then attention turned to a darker matter. The children, David and his three sisters, disliked the woman because she was ‘ostentatiously cruel’. He says she killed hens slowly, relishing, he believed, in the agony of her victims. Then he makes an admission. He sought to witness the killing secretly – by design, rather than accident: ‘For the sight and sounds aroused an emotional tension in me that was at once both repellent and attractive. I would think about it in bed with sorrow and compassion for the bird and yet I would long for the day when I would be old enough to kill one with my bare hands.’

When the family weren’t in Nairn, they lived in Derbyshire and later at Hampstead, London. David was sent to a succession of schools between the ages of five and eleven. He disliked them all. There was one in Buckinghamshire he hated so much he named it Dotheboys Hall, as he was reading Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby at the time and thinking of the gruff and violent Wackford Squeers of the novel. He noted that it was the days before private schools like his were subject to inspection. The couple who ran ‘Dotheboys Hall’ (he doesn’t reveal its real name) punished with punches and kicks and resorted, he says, to starvation – their favourite. A friend of his, Ian Gordon, was locked up for a week, he recalls, because he could not learn by heart the words of the Sermon on the Mount. When David’s parents found out they moved him to University College School in London. It was here that a seemingly harmless incident occurred that had a profound effect on the rest of his life. ‘I remember every detail of that November day during my second year at University College School and of the sleepless night that followed.’

Even with his already poor eyesight, he had attempted to play rugby. Although he says he had strong thighs and could play as a forward, his poor eyesight meant that the ball was invisible for much of the time and the other players were ‘blurred like white ghosts’. During the game that day, he received an accidental kick from someone on his own team just at the side of his right eye. The first result was confusion at Geography class the next day, when a simple exercise in map reading became a problem. His eyes began to be inhabited by shapes and blobs that reminded him of protozoa, the organisms visible when viewing tissue through a microscope.

When his mother brought him to a specialist, a Dr Burnford in Wimpole Street in London, we get a fascinating glimpse of his mother’s emotional life as much as we do of his eye condition. Dr Burnford had, David’s mother said, ‘saved her life’ when treating her husband, David’s father, during the war. The doctor had changed his name from Bernstein to assimilate better in the post-war period in England. He had become, according to her son, a close friend of Annie Finlay Thomson: ‘His sense of humour was something like my mother’s which must have been one reason for her fondness for him, that deep affection which amounted, I now believe, to love.’

Thomson leaves that fascinating thread there. But it’s typical of his willingness to explore emotional matters in his writing. A consultation with another doctor, Mr Maclehose, followed. He maintained that the kick to the head was not necessarily the cause of the haemorrhage behind the eyes, but it may have hastened it. His prescription was drastic for the young David: he was to lie in a darkened room for at least six weeks. His parents read to him during this time. A man came daily from a school for the blind in Great Portland Street to teach him Braille.

The rest of the ‘cure’ was then revealed to him. He describes his mother’s anguish at not knowing which of the prohibitions were worse to a boy of eleven. He had to give up reading and writing entirely until he stopped growing – at twenty-one. He was never to exert himself, lift heavy objects, never to play games, not ‘even cricket’. Running and diving were out, and if he dropped something, he had to feel for it with his hand and avoid looking at the floor. All this was designed, according to the medical knowledge at the time, to prevent the revival of the protozoa in David’s eyes.

Tim Dee, from a later generation of BBC radio producers than David, in a talk he gave on BBC Radio 3, referred to this early period of David Thomson’s life using the image of the floaters that crossed David’s vision as a metaphor. He became a kind of human floater, Dee says, passionately concerned with the stories of the people he recorded or lived among, ‘but also as someone who was somewhere else, who focused those stories through the prism of his own sensibility. The floater is both a separation from and a colouration of what the eye sees. And so, brilliantly, David Thomson, saw, lived and wrote.’ 3

In 1925 David’s parents made what he himself agrees was a wise decision. They sent him to live in Nairn with his grandmother, ‘which benefited me for the rest of my life’. They wisely predicted, he concludes, that doom would beset him in London, if he was unable to do all the things his friends were involved in, that he’d ‘have to hide when the gang came to take me on an evening’s rampage’. It’s possible also that David’s parents were aware of mental fragility at this stage in his life. Martina Thomson reflected on this in 2013, believing that it showed a vigilance regarding their son’s welfare.

David describes in detail the train journey that began this great wrench. He had made it before but always had the comfort of having his family with him, as he had on so many previous journeys to Scotland. It was the 19.30 night train from Platform 13 at Euston. His father had hired him a pillow and blanket at the station. Thomson likes detail; the train needed two engines to haul the carriages up the Camden embankment, passing the street that would be his future home, its construction an aspect of rail engineering history that Thomson would explore many years later in In Camden Town.

As morning broke and Scotland approached, the train thinned out as carriages were detached and the remaining cars joined the Highland Line at Perth, where David describes a surreal encounter – with sexual overtone – as he returned the hired pillow and blanket to a larger-than-life girl who collected them on the platform:

– Twas a braw nicht, I’m thinking, but ye were on your lonesome?

– Aye

– Well now, you’re a canny loon, or look to be. Next time ye travel north, send word for Meg o’ Perth an she’ll go south to bring you. Mind my name well now. Meg. They all know Meg. And Meg will share your pillow wi’ye and we will travel couthie warm togither.

She laughed and pushed her barrow further up the train.

He learnt the names by heart of the stations from Perth to Nairn, ‘like a poem in my head, Dunkeld, Dalguise, Ballinluig, Pilochry’. He and his sisters could recite them: Killiecrankie, Blair Atholl, Struan, Dalnaspidal, and the highest place where a board said ‘SUMMIT’. He remembered his sister Barbara had once made strangers laugh by shouting, ‘There’s another station called Gentlemen.’ A branch line then cut through the Cairngorms with more stops such as Dumphail, Forres, Brodie, Auldearn and then Nairn. This line didn’t survive the cuts of the 1960s and the present route to Nairn goes through Inverness and takes the line to Aberdeen, leaving the stations of Thomson’s childhood as much a part of history as Jacobite rebellions.

The young David arrived in Nairn to a not uncommon discord with an elderly relative. In his case it was his maternal grandmother. Apart from her view of the rebellious Irish, he says she had kind and gentle qualities, but David and she seemed to share a mutual antagonism. After the three years he lived with her, he could only recall acerbity. He speculates that her husband’s early death caused her spirits to sink so low, ‘they were lost to her entirely, buried deep in her unconscious mind as a protection against pain. I cannot remember ever hearing her use my Christian name in the vocative once during those three years.’