7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

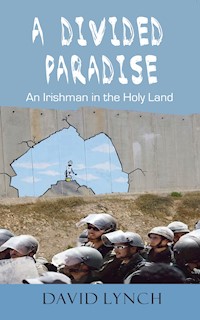

A Divided Paradise: An Irishman in the Holy Land is a vivid account of ordinary life in one of the world's most contested and volatile regions. Award winning journalist David Lynch brings to life stories from both the Palestinian and Israeli street. From coming under fire in the occupied West Bank, to visiting the 'First Irish Pub in Palestine', to talking Armageddon with young dispirited Israelis in Tel Aviv, personal experiences are interwoven with broad historical analysis. A provocative introduction to the political and personal tragedy suffered by the Palestinian people and the continuing wider Middle Eastern conflict.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

Also by David Lynch

Radical Politics in Modern Ireland – The Irish Socialist Republican Party 1896–1904

A DIVIDED PARADISE

An Irishman in the Holy Land

DAVIDLYNCH

A DIVIDED PARADISE First published 2009 by New Island 2 Brookside Dundrum Road Dublin 14www.newisland.ie

Copyright © David Lynch, 2009

The author has asserted his moral rights.

ISBN 978-1-84840-013-9

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

© Map of Lebanon and map of Israel/Palastine on page viii appears by kind permission of Julie Lynch.

Book design by Inka Hagen Printed in the UK by Mackays

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaion), Dublin, Ireland.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, David and Marie

Contents

Maps of the Holy Land

Timeline

Preface

1 Under Fire in Bil’in

2 The Occupation from Behind a Gun

3 The Open-Air Prison

4 Dancing in Ramallah

5 More Than One Wall

6 Loitering on the Margins

7 A Cold House for Arabs

8 Jew Don’t Evict Jew

9 Divided Within

10 Apocalypse Now?

Epilogue

Glossary

Acknowledgments

‘No race possesses the monopoly of beauty, of intelligence, of force, and there is a place for all that at the rendezvous of victory’

Aime Cesaire, (1913–2008) French West Indian poet and political leader.

‘No other conflict carries such a powerful, symbolic and emotional charge, even for people far away. Yet, while the quest for peace has registered some important achievements over the years, a final settlement has defied the best efforts of several generations of world leaders. I too will leave office without an end to the prolonged agony’

Kofi Annan, in his December 2006 exit address as Secretary General of the United Nations.

‘Fanatics have their dreams, wherewith they weave A paradise for a sect’

John Keats, ‘The Fall of Hyperion - A Dream’

Timeline

Some Key Events in the Modern History of Palestine and Israel

1897 – First Zionist Congress held in Switzerland.

1909 – Tel Aviv established north of Jaffa.

1917 – Balfour Declaration issued, announcing British support for a ‘Jewish homeland’ in Palestine.

1918 – British seize Palestine following the defeat of Ottoman Empire in First World War.

1920 – British Mandate over Palestine established by League of Nations.

1929 – Significant riots between Arabs and Jews as Jewish immigration to the Holy Land grows.

1931 – Jewish paramilitary force, the Irgun, is established.

1936-39 – Arab Revolt against growing Zionist power in the region is eventually defeated by British and Zionist forces.

1939-45 – Second World War. Six million Jews die in the Holocaust.

1947 – Britain hands over responsibility for Palestine to the United Nations (UN).

November 1947 – UN proposes the partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states.

1947-48 – The Nakba (Catastrophe), and the exodus of over 750,000 Palestinians from their homes. Refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip take them in.

14 May 1948 – Israel’s establishment proclaimed by their first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion.

1948-49 – First Arab-Israeli War.

1954 – Palestinian resistance group Fatah founded and quickly becomes the largest faction within the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

1956 – Israel, along with France and Britain, attacks Egypt following the nationalisation of the Suez Canal.

1967 – Israel spectacularly defeats Egypt, Jordan and Syria in 1967 War. Israel conquers the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Sinai Desert and the Golan Heights. Following the victory, Jewish settlements are constructed in the West Bank and later in the Gaza Strip.

September 1970 – Jordanian forces attack PLO strongholds in Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan and thousands die. The period is later called Black September. PLO leadership is forced out of Jordan and eventually relocates to southern Lebanon.

1973 – Israel defeats Egypt and Syria in Yom Kippur War. Israeli victory is less conclusive than in 1967.

1977 – The right-wing Likud party wins Israeli general election ending decades of Labour Zionist control. The building of settlements in the West Bank and Gaza intensifies.

1978 – Egypt and Israel sign Camp David Peace Accords. The Sinai Desert is returned to Egypt, and Egypt fully recognises the Israeli State.

1982 – Israel invades Lebanon. The PLO and its leader, Yasser Arafat, are forced out of Beirut.

1987 – The first Palestinian uprising, the ‘intifada’, explodes in the occupied territories.

1990-91 – First Gulf War. Iraq launches SCUD missiles at Israel.

1993 – The Oslo Accord is signed between the Israeli government and the PLO. The first peace agreement between Israel and Palestine.

1994 – Yasser Arafat triumphantly returns to Palestinian territory in Gaza, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) is established.

1995 – Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin is assassinated by extremist Jewish rightwinger.

2000 – The Camp David peace negotiations between Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat collapse. In September the second intifada begins on the streets of the occupied territories.

February 2001 – Likud Leader Ariel Sharon wins Israeli general election.

September 2001 – Suicide attacks by AI-Qaeda on United States kill almost 3,000 people.

2002 – Operation Defensive Shield takes place, with Israel attacking the Palestinian cities on the West Bank.

2003 – United States military lead an invasion of Iraq.

November 2004 – Arafat dies in Paris. Mahmoud Abbas becomes leader of PA and PLO.

January 2005 – Mahmoud Abbas wins Palestinian presidential election.

August 2005 – Gaza Disengagement. Jewish settlers are removed from the Gaza Strip.

January 2006 – Hamas wins Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) elections.

January 2006 – Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon suffers a major stroke, ending his political career.

March 2006 – Kadima wins Israeli elections and Ehud Olmet becomes prime minister.

July – September 2006 – Border skirmishes lead to Second Lebanon War. Israel invades southern Lebanon and attacks cities including Beirut. Hezbollah fires rockets at northern Israeli towns and cities.

May – August 2007 – Lebanese forces attack Nahr al-Bared Palestinian refugee camp to destroy a small terrorist cell. Political instability continues across Lebanon with a series of car-bombings and assassinations in the capital and elsewhere.

June 2007 – Vicious street battles between Hamas and Fatah gunmen in Gaza spiral towards a civil war. Hamas takes full control of Gaza and Fatah takes the West Bank.

May 2008 – Israel celebrates 60th anniversary of its establishment with major celebrations and visits by international leaders, including US President George W. Bush. Palestinians mourn 60 years since the Nakba.

Preface

Israelis are enjoying their state’s 60th birthday. There are barbeques on the beach, spectacular aerial displays over the Mediterranean coastline and military parades through public parks. The May weather is predictably beautiful for the Holy Land, and there is an atmosphere of excitement that belies the usual tensions in the major cities.

The local Hebrew media has produced bumper commemorative supplements to mark 60 years since the May 1948 foundation of the state. But it is the final of the Israeli ‘Survivor’ reality TV show, the upcoming Eurovision Song Contest and the gripping end to the Israeli soccer season that take up most tabloid print acreage and ordinary conversation.

Here in the secular parts of Jewish West Jerusalem morale is high. A technology-based boom continues, tourist figures have started to increase and violence within Israel has dropped dramatically. Maybe Israel at 60 is not a ‘light unto the nations’ as its most optimistic of supporters maintained it would be, but the surface of everyday life in Israel makes it feel like ‘a normal country’ as the first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion had hoped for.

Twenty minutes’ drive east from the packed cafes and restaurants of West Jerusalem’s lively pedestrian streets and shopping malls is the occupied Palestinian West Bank. Stinging tear gas swirls in the air; deafening stun grenades, low-flying military helicopters, speeding Israeli army jeeps and the crackle of gunfire greet you.

Israeli soldiers clash with Palestinian protestors outside the Kalandia refugee camp.

The protestors carry the Palestinian national flag and large cardboard keys. The keys symbolise the refugees’ homes, lost 60 years ago. For while Israeli Jewish society happily commemorates 60 years since the Israeli Declaration of Independence, the exact same historic moment marks the beginning of the Palestinians’ national tragedy.

Their Nakba (Catastrophe) also occurred in 1948, and demonstrations, public meetings, literary readings and art exhibitions are held across Palestinian society to commemorate the event. The Nakba is mourned in the occupied territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, within the Palestinian refugee camps in the neighbouring Arab states and among the Arabs who live in Israel, who make up one fifth of that country’s population.

In the occupied West Bank, some of the protests descend into violence as Israeli troops blast tear gas and fire rubber bullets at demonstrators. Later that evening, off-duty Israeli soldiers will sip their coffee in the bars of West Jerusalem while watching the Israeli soccer State Cup Final on outdoor TV screens.

Two peoples, two narratives, two realities.

But behind the clear contrast in the everyday divided experience of Israelis and the occupied Palestinians, there is a more complex, interconnecting story. Israel is not a country just like any other.

This book weaves together personal experiences, anecdotal evidence, traditional reportage and historical and political analysis. It is based primarily on my stay during the summer of 2005 in the West Bank Palestinian town of Bir Zeit. During that period I studied Arabic at the local university and wrote a series of articles for The Sunday Business Post on life under occupation and the ‘Gaza Disengagement’, when the Israeli state pulled Jewish settlers out of the Gaza Strip.

I returned to the Holy Land in March 2006 in order to cover the Israeli general election and life in the occupied territories for Daily Ireland. There had been a shock result in the Palestinian election in January of that year when the Islamic party, Hamas, rose to power. In May 2007, I travelled to Lebanon to gain an understanding of what life was like for Palestinian refugees in that region. At the time, tensions between the various factions in that divided country were growing, with car bombs exploding regularly in the capital Beirut. The Lebanese Army was bombing a Palestinian refugee camp in the north of the country in what they claimed to be an operation to destroy a small terrorist cell.

My most recent trip to the Holy Land came a year later, to cover the 60th anniversary celebrations for Israeli Independence and the parallel Palestinian mourning of six decades since their Nakba.

The contemporary world contains a long roll call of oppressed peoples whose circumstances demand our interest, sympathy and support. From the Kurds, who remain stateless and the victims of repression by various nations, to the Tibetans whose occupied country is under increasing centralised military control from Beijing. There are many others whose stories hardly ever generate newsprint.

Over the past decade, still more occupied peoples have joined the list of those who wake in the morning, peer out from their windows and see foreign troops on their land. War is being unleashed in their midst, from the Iraqis, to the Chechens and the Afghans to mention but a few.

Such national bondage is not a new historical phenomenon, but since the era of colonialism through today’s imperialism, it has rapidly intensified. The indigenous populations of the American, Australian and African continents were early victims. In Europe, in the nineteenth century, the high-profile struggles for independence by the Irish and the Poles captured the imagination of progressive, left-wing individuals and political movements. The twentieth century witnessed a whole series of successful anti-colonial struggles sweep across Africa and South East Asia. Yet despite the end of the Cold War, justice and freedom does not reign freely within a ‘new world order’ dominated by the United States.

Africa, with its famines, wars and pandemic diseases, is the contemporary home to those who suffer most desperately under the iniquitous global system. But it is in the Middle East where the forceful and bloody military actions taken by western powers and their client states to shape the world in their selfish interest are most clearly at work to the objective observer. The conflict between the State of Israel and the Palestinians is the long-standing touchstone issue in this region.

The Palestinian struggle for freedom inspires millions of Arabs and others across the globe who also fight against occupation and tyranny. This struggle has become for some a singular example of all the injustice in the world. It is an explosive political situation that contains within it all of the basic elements of oppression, inequality, hegemonic power and resistance. A ‘solution’ to the conflict based on justice is therefore believed by millions to be a prerequisite to world peace and stability.

In this context, the primary role of journalists should be both to bear witness to the complexity of events and to attempt to write truth in the face of power. Those in the modern world who have access to almost unassailable economic control and military might have little need for ever more literary and media support. Therefore, the conflict on which this journalistic-historical account focuses is one of the complex lives on both Israeli and Palestinian streets.

It is difficult to conceive how anyone who is aware of the facts or who has experienced them at first hand could not be clear in their minds as to who the principal victims and oppressed are in this particular situation.

Yet some still support the occupier. These include the political leadership of the world’s only superpower who has for many decades pursued a policy that lends unlimited support to those who occupy and take land, while also attacking, denigrating and deriding those who live under occupation or who are exiled in refugee camps.

This book, while honestly attempting to portray the often hurt, diverse and divided everyday existence in Israel, will unashamedly and sympathetically chronicle that which has lost the most over the past six decades of Middle Eastern history – the tragic Palestinian nation and its defiant, inspiring people.

David Lynch, Jerusalem, 2008.

1 Under Fire in Bil’in

The angry demonstrators stood within inches of the soldiers. They were chanting loudly, screaming straight into the faces of the young armed men who were partially hidden under their large, green helmets. The soldiers seemed unmoved, barely twitching despite the close-range sonic onslaught. Their eyes showed no signs of fear or anger; many covered them with dark sunglasses. The bright Middle Eastern sun glistened against the armoured jeeps.

I was standing on a rock a couple of metres behind the front line of protestors, trying to get a better view. A rotund, thirty-something stranger wearing a keffiyeh tight around his neck, was standing beside me. He turned to me, smiled and asked where I was from.

‘Ireland.’

‘Ireland, wow! Have you gone to any of the Irish bars in Tel Aviv? Some of them are very cool,’ he said.

‘No. Are you from Tel Aviv?’ I asked.

‘Yes.’

I paused for a second.

‘Are you Jewish?’

‘Yes,’ he laughed.

I had found myself in some odd situations during the first month of my stay in occupied Palestine, but this was already competing to be one of the most surreal.

I was positioned within the main body of a protest in the small West Bank village of Bil’in. A line of determined-looking Israeli soldiers had prevented our group, numbering approximately 200, from walking any further along the road north out of the village. It was Friday afternoon, following Muslim prayers, and the intense sun blazed above. The situation was peaceful, but there was an unmistakable tension along the narrow dusty road.

This was not where I had expected to spark up a conversation with a Jewish resident of Tel Aviv regarding the social highlights of his city, and certainly not an Israeli Jew wearing the black and white scarf that, more than any other item of clothing, symbolises the Palestinian struggle for independence.

‘I only stayed a couple of nights in Old Jaffa south of Tel Aviv when I got here last month,’ I said.

‘Oh yeah, Jaffa can be very nice. But you should come to Tel Aviv as well – it is not too far away. There are many Irish bars – it would be like home for you, maybe,’ and he laughed again before continuing. ‘Molly Bloom’s is a great Irish bar. You would love it, coming from Ireland. I was there on St. Patrick’s Day this year. They had to close the street in front of the bar, there were so many people. You could go outside and drink plenty of Guinness,’ he said while motioning his two hands up to his open mouth as if drinking deeply from a black and white creamy pint. He chuckled.

I was not really in the mood for laughing. I was at that moment questioning my sanity, wondering why I had decided to attend the protest.

The weekly demonstration held in the village situated approximately 16 kilometres west of Ramallah had begun five months previously, in February 2005.

What the Palestinians call the ‘apartheid wall’, the Israelis refer to as the ‘security fence’, and what the International Court of Justice had ruled to be simply illegal, was due to be constructed through large swathes of Bil’in’s hinterland. The imposing structure, hundreds of kilometres long, had already begun to dominate the arid landscape in many parts of the West Bank.

Local residents claimed that the Wall would ‘steal’ much of the villagers’ land, and cut Bil’in off from other Palestinian economic centres. In short, it would be a calamity, and weekly demonstrations had been organised to try to stop it.

‘What are you doing over here?’ the man from Tel Aviv enquired.

‘I am working and studying. I am learning Palestinian history and colloquial Arabic at Bir Zeit University, you know the place? It’s just outside Ramallah. I am also a journalist and I am filing stories for a paper in Dublin from here.’

‘What stories?’

‘Well, this week I’m working on an article about these gatherings and protests in Bil’in. I think I might now focus on the Israelis who attend them. Israelis like you, I suppose.’

He smiled and nodded his head.

I peeked over the Israeli man’s shoulder and focused on the increasing friction at the front of the protest. A line of some 20 fully-armed Israeli troops stood two deep, blocking our way across the narrow potholed road. The bulk of the demonstrators were local Palestinians, but there was also a minority of Israeli and international peace activists. Near the back of the march was a small group of young people who had travelled from the Basque country. They were in high spirits, chanting in broken English, Arabic and flowing Basque. I did, however, speak to one pretty Basque woman with long black hair who bemoaned the fact that most people, even at the Bil’in march, mistakenly believed herself and her comrades to be Spanish.

The protestors clapped and chanted anti-occupation slogans in Arabic, Hebrew and English. As we marched briskly forward, our intended destination was the disputed area on which the Wall was due to be constructed. However, the Israeli military had long since deemed this part of Bil’in to be militarily sensitive and out of bounds for the local residents. They did not intend to allow us through and had declared the protest illegal.

More soldiers had now spanned out to the right and left of us, taking up positions among the sparse olive tree grove. The protestors’ chanting had ceased. Other Israel Defense Force [IDF] troops stood on mounds of dirt alongside the roadway, filming the demonstration with their hand held digital cameras. A number of protestors stood a short distance from the Israeli lines, filming the soldiers with their own video cameras. Whatever was going to happen would be extensively recorded, from all perspectives.

The weekly Bil’in protest almost always ended in Israeli army attacks, which were then subsequently given high profile coverage in the Arabic media. The previous Friday, a 24-year-old local Palestinian, Ramzi Yasin, was shot in the head causing him extensive injuries. It was later reported that he had serious brain injuries that had caused him lasting sight problems. A number of other protestors were also hurt during the Israeli action.

The marchers once again renewed their chanting and furious clapping. Some were shouting directly at the soldiers, or waving huge green, black, white and red Palestinian flags. Others carried the banner of the Israeli peace group, Gush-Shalom. A Palestinian man in a wheelchair was at the front of the protest, screaming at the Israeli soldiers in Arabic. He moved his wheelchair violently back and forth against the front line of troops, waving his arms angrily. The rocky, uneven road was anything but wheelchair-friendly and this man had to push determinedly down upon the wheels to make any progress.

Organisers addressing everyone in the village community centre prior to the march had told us that this protest was to be peaceful. No stones were to be thrown at the army lines by anyone involved in the demonstration. One speaker asked people not to run if the IDF began to fire on us.

‘It is more dangerous when everyone runs together,’ explained a member of the global Palestinian support organisation, the International Solidarity Movement (ISM), sporting dreadlocks and an American accent.

To my militarily untutored eye, it now looked like the soldiers were starting to move into some pre-planned formation. Troops marched out even further to the east and west of the road, worryingly outflanking the tight knot of protestors. It was difficult to get a sense of how many Israeli troops had been deployed or where exactly they were in relation to the demonstration. I was feeling more than a little trapped.

‘You look nervous, my friend. You are not used to this sort of thing in Ireland? It’s a dangerous place, no? You hear all the news reports of violence … I suppose not as much now.’

‘Well, not at the moment and not in the part of the island I am from anyway,’ I said.

‘You have peace now, yes?’

‘Well, yes,’ I answered quickly.

‘That is great. I am happy for you and your people, we can only pray that peace will eventually come here one day as well. But as we stand here, that day looks very far away,’ he said nodding his head and pointing towards the IDF.

‘You have been to Bil’in before?’ I asked the friendly Tel Aviv resident. I was beginning to think I should be more professional, stop worrying and ask some questions.

‘Oh yes, many times.’

‘You do not worry? Not at all?’ I asked.

‘About what?’

‘Getting shot,’ I said directly.

‘Well, it is not so dangerous for the Israeli protestors really. They will try not to hurt us. It would look very bad in the media back home. But for the Palestinians, the locals, yes, it is dangerous.’

‘What about for foreigners?’ I asked selfishly.

‘Hmm. You are somewhere in between.’

‘Journalists?’ I asked, thinking that I might get my National Union of Journalists membership card out and hang it prominently around my neck.

‘You are also somewhere in between,’ he playfully giggled like the Bil’in veteran that he obviously was.

‘Why? How so “in between”?’ I enquired anxiously.

‘Well, sometimes you do get hurt – it’s hard to say. Don’t worry too much about it, you are here now. There is nothing much you can do now, is there?’

He smiled again, this time sympathetically.

I wanted to ask him about his motivations for being in Bil’in. Why was he not using his final hours before the weekly Jewish holy day, Shabbat, to walk along the beautiful, idyllic Tel Aviv promenade on the Mediterranean, rather than spending it here in the occupied territories? Why was he trying to defy the law and his own military to take part in an illegal protest? It was also potentially dangerous for Israeli citizens to travel outside the Jewish settlements in the West Bank. What were his feelings about the current state of the Israeli ‘peace movement’?

But more pressing concerns shaped my questions for now.

‘Do they always fire on the crowd?’ I asked.

‘Yes, always,’ he said honestly.

‘But how does it start?’

‘They say they are attacked. They lie.’

‘Are you sure nobody throws stones?’

‘Well, yes, eventually the local teenagers sometimes start throwing them after the soldiers attack us. I have no problem with that, some do. They feel like they are protecting their village from the army, even if it is only with stones. I understand that. Anyway – stones, can they do so much harm? Look how protected the soldiers are and look what they fire back at us.’

‘Still, it would surely be better for the organisers if none were thrown at all,’ I said.

‘Well maybe, yes. But they are not thrown until the protestors and the villagers are attacked. Anyway, look what we are doing. We are building this Wall on their land. We are stealing their land. Why? Because we can. This is the real tragedy here. When I think of what our people have been through, and now what we are doing to another people, it makes me angry.’

He again pointed towards the mass ranks of Israeli armed forces. Jeeps had brought more troops to the scene from behind the Israeli lines. The crowd was again chanting loudly in Arabic, Hebrew and English: ‘Free Free Palestine’ … ‘This Wall has got to fall’ … ‘Free Free Palestine.’

‘You drink in Molly Bloom’s, so?’ I asked.

‘What? Say that again,’ the Tel Aviv man replied. He couldn’t hear me above the growing communal chorus.

‘You like Molly Bloom’s?’ I shouted louder.

‘Ah yes, Bloom’s. A great bar. I will give you my email address and number – if you ever come to Tel Aviv, maybe we can meet up?’

‘That would be cool. It’s interesting, you might not know, but Molly Bloom was Leopold Bloom’s wife.’

‘Ah yes, Ulysses, James Joyce,’ he said quickly.

A rush of pathetic literary patriotism enveloped me as I heard the Irish literary classic mentioned in a West Bank village. It briefly took my thoughts away from the burgeoning tension around me.

‘You know it?’ I asked smiling.

‘Of course,’ he said nodding and grinning back.

‘The main character in the book is Jewish. I studied it while in college back in Ireland, there is a lot in it about Irish and Jewish identity and stuff like that,’ I said rapidly.

‘Yes. I have seen a copy of it in Hebrew. I think I read that it was only translated in the 1980s.’

‘Hebrew! How do you translate passages like “shite and onions” into Hebrew!’ I said, laughing.

There was a female scream from the front of the march. I forgot about Joyce and focused on Bil’in. There was some slight pushing and shoving between a couple of protestors and troops. Suddenly there was a deafening explosion to my left. My left ear began ringing. Then there was a quick, razor-sharp piercing pain. I thought that maybe my ear drum had burst. I bent forward and rubbed the left-hand side of my face. It felt like I was bleeding from my ear, but it was only sweat that rolled down my left cheek. To my right I saw some of the protestors running. There was another shattering sonic bang ten metres or so down the dusty path towards the village. The loud explosions from stun grenades signalled the beginning of the Israeli push. I was dazed and substantially deafened. I stood up straight and looked back at what was left of the front line of the protest, the group rapidly dwindling in number.

Protestors were now running past me, back towards Bil’in as the Israeli attack developed. The Israeli soldiers began advancing methodically. They walked around the Palestinian man still screaming from his wheelchair. A combination of fear and foggy confusion kept me stationary. As I stood rooted to the spot, there was another large explosion. A stun grenade erupted close by. Small brush fires had started on either side of the road in the tinder-dry grass. At that moment I heard a low, soft thud and I saw something sail over my head. A tear-gas canister landed a few feet away. It exploded. There quickly followed a series of further thuds as more tear gas was lobbed into the clear blue sky over the heads of the fleeing protestors. The majority of demonstrators had begun to retreat quickly towards the village. I was still unsure on my feet and highly disorientated. My hearing was muffled. Somebody pushed into my back. I moved forward unsteadily. Another protestor standing close to me roared in English to nobody in particular.

‘They are starting to fire from the trees.’

Something in that roar shook me from my momentary paralysis and broke through my partial deafness. I started to run, fast, towards Bil’in. The thick smoke from the tear gas was swirling in my path. A cloud of heavy gas now hung over the village’s northern periphery. I ran through it. Behind me I could hear the mumbled cries of people shouting and screaming. I looked quickly behind and saw a number of Israeli soldiers break free from their front lines and chase retreating protestors. Some carried long batons and heavy riot shields and swung out violently at fleeing protestors.

From the edge of my line of vision I spotted the Israeli soldiers who had taken up positions adjacent to the road. They were crouched down on their knees, taking up firing positions amongst the olive trees and behind the small broken walls surrounding tiny plots of farmland. Some were cocking their guns towards us.

Having read and studied so much about this conflict in the previous months and years only one salient fact crystallised clearly in my head: the IDF has a consistent killing rate in the West Bank. The vast majority of victims are of course Palestinian, but it also has a record of killing foreigners and journalists. Since October 2000, ten foreign citizens have been killed by the Israeli military, and there have been some high-profile cases, such as the fatal shooting of British filmmaker James Miller in 2003.

I stumbled along as fast as I could. I saw a young woman who had fallen to her knees on the dust road. She was starting to vomit. A fellow protestor had gripped her shoulder and was desperately trying to lift her and pull her towards the village. Another clearly distressed and not so young man was holding his face and moaning.

Then it hit me.

My face grew progressively numb. My eyes felt like they were contracting and excreting some sort of ooze with great difficulty. I had to stop. The tear gas had got me. The gas was rapidly paralysing part of my face. I took a bottle of water from the pocket of my combats and tried to walk forward. Then I stopped again, holding the bottle open ready to pour into my cupped hand to throw onto my face.

I could not remember whether you’re supposed to throw water on your eyes or not after being hit by tear gas. Something had been said at the meeting before the protest march began. But I could not focus clearly enough to remember. The blasts from the stun grenades continued behind me. They were starting to get closer. My mind was swirling with undefined fright, noise and pain. My face felt like it had been invaded by some silent numbing conquering army, bringing nothing but stinging pain in its wake.

There were a series of further explosions, again some metres behind. People were still running past me. I dropped my water when I began to run. Clasping my hands over my face I tried to race forward in self-imposed darkness over the rocky road, peeking painfully through my burning eyes. I could hear people fleeing, chanting, shouting and screaming both past me towards the front line, and by me into the village. The tears streamed down my cheeks as I rubbed my face furiously. I continued running unsighted.

After maybe 80 or so metres it got quieter; I could still hear the sound grenades and the thuds from the tear gas canisters being fired, but now from a somewhat safer distance. I slowed down to a walk. My eyes felt like they had been dipped in vinegar. The pain was building again.

I then felt a light pull on my left arm. I did not remove my hands. Something pulled me again this time a little harder. I stopped. I removed my hands from my face and opened my eyes slowly.

In front of me stood a small smiling Palestinian boy in a ragged short sleeve t-shirt and shorts. He was holding a wide tray full of sliced onions. He pointed at the two pieces of onion shoved up his nose. I grabbed two slices of onion and with some force sent both of them northwards up my nostrils.

‘Suckran kitiir (thank you),’ I mumbled in my rudimentary Arabic, thanking him as he ran off to help others, delivering sliced onion to pained protestors.

I rapidly looked around through my almost fully closed eyelids. I seemed to be well away from the main contingent of protestors and close to the houses on the northern edge of Bil’in. The man from Tel Aviv who I had been talking to earlier was nowhere to be seen.

I saw a large flat rock to my right and it was with some desperate relief that I went and sat down hard upon it.

*

Bil’in is a rural village of some 1,800 residents. It is much like any other West Bank village. Local life is sustained, as it has been for generations, by agricultural living, particularly olive harvesting. Its bumpy, cratered, dry streets are common across the Palestinian territories occupied by Israeli forces, a place where major infra-structural investment in modern road surfaces is almost wholly restricted to roads which only Israeli Jews may use. The rhythm of its everyday existence is equally average, with a life built around the cycle of Islamic and Christian worship, and seasonal agricultural labour. This peaceful timetable is randomly shattered by military incursions and the unpredictable vagaries of life spent living under an occupation. The town is located approximately five miles east of the ‘Green Line’, the invisible, globally recognised border between Israel and the lands that it has occupied, including the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, since the 1967 War.

The Israeli military occupation is an integral feature of everyday life in Bil’in, as it is in hundreds of similar Palestinian villages, towns and cities across the West Bank. The locals learn to live with frequent army raids, military checkpoints and night-time arrests. Adjacent to the village are a number of Jewish settlements. These settlements, which Palestinians cannot enter, have wide, modern, suburban-type roadways, housing estates, functioning sewerage and plumbing systems, and sometimes, in a region plagued by water shortages, swimming pools. Many have facilities that the people of Bil’in could only dream of.

Since the 1967 War, successive Israeli governments have continued to build settlements for Jewish residents in the occupied territories. Over the past two decades, settlement construction, deemed illegal under international law, has risen sharply. By 2004 there were in excess of 400,000 Jewish settlers living on the Palestinian side of the Green Line. Due to the construction of the settlements and the vast road and military networks they have spawned, the Israeli authorities now directly control 60% of West Bank land. The Israeli military has de facto control over the rest of the West Bank, despite the very limited power exercised by the Palestinian Authority (PA) in some urban areas. The Jewish settlements near Bil’in are built on part of that Israeli-controlled land.

A complex web of modern motorways and tunnels connect these settlements to the major Israeli cities, like Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Though Jewish settlers are permitted to use these roadways, Palestinian motorists are banned. Large-scale Israeli military installations have been built on the Palestinian West Bank to provide security for the illegal settlements and to facilitate military operations throughout the territories.

Bil’in’s colourful mosque on what passes for its main street is certainly more aesthetically pleasing than many of the mundane white mosques dotted along the undulating hills of Palestine. However, when you walk past the numerous half-built two-storey white buildings and look out from the edge of the town over the West Bank, there is nothing particular to distinguish this village from any other.

Despite appearances, Bil’in is in fact significant to the greater picture of the Middle East. The trials and tribulations of this tiny place have since February 2005 been regularly splashed on the front pages of Israeli, Arab and international papers, and the town has hosted international conferences focused on the Wall and the Israeli occupation. West Bank residents have been known to affectionately refer to Bil’in’s inhabitants as ‘Palestinian Gandhis’, for the villagers welcome peace activists from across the globe with open arms. They have suffered sustained military attacks by the Israeli army, but in the face of this, Bil’in has become a byword for a potential paradigm shift in the politics of resistance within the occupied territories, a cause célèbre for Palestinian solidarity activists and supporters around the world. For some, the town is now a pivotal example of sustained peaceful protest, and a regular forum for new ideas and developments in the Palestinian resistance. This progression has taken root from the widespread dissatisfaction among Palestinians and their supporters with the Palestinian leadership during the second intifada.

In 1987, a major Palestinian uprising against the Israeli occupation began. What is referred to as the first intifada (literally ‘shaking off’ in Arabic) witnessed strikes, demonstrations and peaceful protests across the Palestinian territories against occupying forces. (Although rather simplistically, the lasting international image of that uprising tends to be of a lone Arab boy throwing a stone at an Israeli tank.) Israeli troops had permission to shoot at unarmed Palestinians who raised their national flag. The first intifada won the Palestinians much international support as the nature of the uprising starkly exposed the massive military gap between the occupier and the occupied. The intifada petered out in the early 1990s as the peace talks that eventually ended in the Oslo Accords were signed.

The second intifada began in late 2000, and was characterised more by militarised resistance by Palestinians. It was sparked by a visit of the then Israeli right-wing opposition leader, Ariel Sharon, to the mosque compound of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, a place holy to Muslims. Sharon was conscious of the violent reaction that his heavy footsteps would ignite, as he crossed that sacred ground. That said, the roots of the uprising had been watered for many years prior to Sharon’s intentionally provocative visit.

The roots of the second intifada took hold as a result of Palestinian disillusionment with the Oslo Accords signed in 1993, the collapse of the Camp David peace talks in 2000 and the continued Israeli occupation. This disillusionment and resulting violence was captured by the Western media in footage of Israeli civilians killed by Palestinian bombings. In thinking of violence in the Holy Land, most in the West can call to mind horrific images of human remains strewn across public streets, the bodies of innocent Israelis who moments before had been eating in restaurants and dancing at discos, killed by Palestinian suicide attacks.

Suicide bombings did indeed play a significant role in the second intifada, a role they had not during the first. However, the second uprising was also characterised by mass civil disobedience and widespread military resistance to the Israeli army, which was not always reflected in the international media coverage. The second intifada also saw a continuous stream of vicious Israeli military attacks on Palestinians on a scale much larger than that of the 1980s. The crude arithmetic of the second intifada’s body count displays clearly that Palestinian civilians suffered the most.

A great deal of blood has been shed on both sides of the Green Line since the outbreak of the second intifada. Between October 2000 and May 2008, over 4,700 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli security forces within the occupied territories, with a further 65-plus killed within Israel itself. Of those killed in the territories, over 940 were minors. In Israel, more than 480 civilians have died at the hands of Palestinians, with a further 236 killed within the territories. Over 300 members of the Israeli security forces have also died during the second intifada.

Many Palestinians and solidarity activists rejected the so-called ‘militarisation’ of the most recent intifada as both ethically questionable and politically foolish. Others have invested little hope in ‘peace talks’ between the leaders of the PA and Israeli government officials. This despair followed a series of false negotiated dawns which had inspired much hope but ended with no justice and no peace. It was in this context of disappointment, discussion and debate about the future that in early 2005, Bil’in, an innocuous, historically unimportant Arab town, became the focus of peaceful mass action based on Israeli-Palestinian solidarity with international cooperation. The converts to the movement inspired by Bil’in pointed to its fresh thinking and activism within a resistance that seemed strategically directionless and badly led in the face of Israel’s military might.

In the summer of 2002, then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon gave the go-ahead to what Israel calls a ‘security fence’. The radical idea behind this massive project had swirled around Israeli military and political circles for some years. The Israeli government argued that its construction would prevent Palestinian suicide bombers from targeting civilians in Israel’s urban centres. They said it was to be built close to and sometimes along the Green Line. The authorities also promised that it was a ‘temporary’ measure.

Among Palestinians living behind the monumental construction that now weaves its way across hundreds of kilometres of the Holy Land, the perception was of course very different. Political leaders called it simply a ‘land-grab’ by Israel, taking still more Palestinian territory. They argued that the Wall was not in fact destined to be built along the Green Line, but rather, deep inside the West Bank, thus stealing Palestinian land. It would also serve to cut off villages, choking the economic and social life of the many towns situated close to its route.

Almost six decades since the creation of the Jewish state, nothing quite summed up current Israeli-Palestinian relations like this 400-mile barrier.

Firstly, the Wall is a physical expression of the iniquitous relations between both sides. Israel can, without any practical opposition from the PA, and in the face of international pressure to desist, build its Wall inside the West Bank – essentially wherever it wants. The Wall encircles Palestinian towns, cuts off communities and families, and, the PA argues, it completes the strangulation of the already enfeebled Palestinian economy. It is a unilateral act carried out by the Israeli government without any consultation with the Palestinians, and despite an International Court of Justice 2004 ruling that its construction is, in fact, illegal. It is a physical manifestation of Israel’s occupation and oppression of the Palestinians.

Secondly, it is a visible representation of the Israeli fear of Palestinian suicide bombings that partially fuelled the right-wing shift within internal Israeli politics and society since 2000. An opinion poll widely published and commented upon in Israel in March 2006 showed that a significant number of Israelis did not want to have any interaction with Arabs at all. The poll reflected an intensification of trends that had been outlined in previous data.

This survey conducted by the Israeli Geocartographia on behalf of the Centre for the Struggle Against Racism made some shocking findings: nearly half of Israeli Jews said they would not allow an Arab into their home. Forty-one per cent said that they would like segregation of social facilities, much like the ‘petty apartheid’ that had existed in the old South African state. Forty per cent said that they would like to see the government help to ‘remove’ the Arab population that lives within Israel’s borders.

During the peace process in the early 1990s, much of the overtly optimistic rhetoric on both sides was about ‘coexistence’ and ‘cooperation’. This sort of dovish jargon has since been binned. The failure of the process to provide peace and justice has led to intense disillusionment among both Israelis and Palestinians. The majority of those who describe themselves as part of the Israeli peace camp now speak in terms of ‘separation’ as the only viable path to peace, as do many Palestinians.

For example, Peace Now, the central non-party political group at the heart of the peace movement in Israel, does not oppose the Wall per se. Rather, it argues that it should not be built within the West Bank, but on the Green Line.

The Israeli security establishment highlights as a success the decrease in Palestinian suicide attacks since the construction of the Wall started. The Palestinian side maintains that it was the 2006 decision by Hamas to abandon suicide attacks that has lowered the number of bombings. But with the support of Israeli citizens in the face of international pressure, and with Palestinians relatively powerless to stop it, the foundations of the Wall were begun in 2002 and its construction continued into the summer of 2008.

The Palestinian body politic was paralysed. They could do nothing to prevent the continued building of this Wall on its territory. There were some localised, almost spontaneous sparks of resistance on a micro level among Palestinian villagers. One such village was Bil’in. Local activists claim that the Wall, if completed, would cut off 60% off the town’s farmland. The land which the villagers describe as ‘stolen’ would then become the site for a new Jewish ‘city’, established following the planned extension of five existing Jewish settlements in the locality.

*

While sitting down on the rock just outside Bil’in, I watched young Palestinian teenagers gather in a huddle. I was trying to get my thoughts together and deal with the pain in my face. I saw the teenagers move apart. They then separated out among the olive trees on both sides of the road at the edge of the village.

I could see a number of them take slingshots from their jeans’ pockets. As if one, they began to fire stones from the impressively large slingshots, swinging wildly and yet carefully controlled over their heads. The speed at which the slingshots were loaded and released was mesmerising. This was no scattergun approach. With a sharp flick of the wrist, at just the right time, the stone was released swiftly, hurtling towards the Israeli soldiers.

In what was essentially an attempted counter attack on the Israeli forces moving down the road towards the village, the local teens took to the fields. Each stood a few feet from the other, fanning out in a curved line away from the road. There was a constant level of whistling going on between them, pointing and shouting as tactics were brought to bear.