18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Phillimore & Co Ltd

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

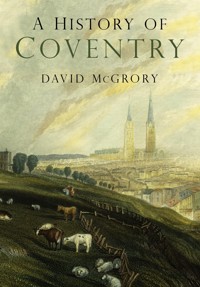

The author, well known as the writer of more books on the city than anyone, explores Coventry's history from Roman times through Earl Leofric, Godiva and the Norman castle, to monastic houses, including St Mary's priory. Coventry has a rich medieval heritage, and rose to power in the Wars of the Roses, when the royal court moved there. Major themes in the city's history are discussed, through previously unknown source material, covering the Siege and Civil War, education, health, the church, crime and punishment, and industries from medieval weaving to modern car-building.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

LOOKING FROM CROSS CHEAPING INTO BROADGATE CIRCA 1750 (19TH-CENTURY ENGRAVING BY GEORGE WEBSTER).

First published 2003, 2004

This paperback edition published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© David McGrory, 2003, 2004, 2022

The right of David McGrory to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9766 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

FOR MY HEATHER WITH LOVE

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

ONE Beginnings

PREHISTORY – ROMAN COVENTRY – SAXON COVENTRY AND OSBURGA – LEOFRIC, GODIVA AND AELFGAR – THE HOUSE THAT LEOFRIC BUILT? – THE EARLY BISHOPS – THE EARLS OF CHESTER AND COVENTRY CASTLE

TWO Medieval Coventry

THE EARL’S HALF AND THE PRIOR’S HALF – CHURCHES AND MONASTERIES – THE CITY WALL – ROYAL VISITS – THE GUILDS OF COVENTRY – LIFE IN MEDIEVAL COVENTRY – CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

THREE Lancastrian Coventry and Henry VI

A ROYAL CITY – THE ROYAL COURT MOVES TO COVENTRY – WAR – COVENTRY CHANGES SIDES – RELIGION – CRIME AND PUNISHMENT – DAILY LIFE

FOUR Tudor Coventry

HENRY TUDOR – THE VENERATION OF HENRY VI – LAURENCE SAUNDERS – RELIGIOUS REBELLION – DISSOLUTION – DOOMSDAY OF THE MYSTERY PLAYS – THE COVENTRY CROSS – ELIZABETH AND MARY – EDUCATION – CRIME AND PUNISHMENT – DAILY LIFE

FIVE Seventeenth-Century Coventry

ROYAL VISITS – GREAT REBELLION AND GLORIOUS REVOLUTION – RELIGION – CRIME AND PUNISHMENT – EDUCATION – EVERYDAY LIFE

SIX Everyday Life in Eighteenth-Century Coventry

EDUCATION AND RELIGION – CRIME AND PUNISHMENT – LEISURE

SEVEN Nineteenth-Century Coventry

INDUSTRY – EDUCATION – ENTERTAINMENT –CRIME AND PUNISHMENT – RELIGION

EIGHT Coventry in the Twentieth Century

HOUSING, HEALTH AND PUBLIC SERVICES – INDUSTRY – TWO WORLD WARS – REBUILDING THE CITY

Notes

Select Bibliography

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

FRONTISPIECE: Coventry Cross

1 Tumuli and standing stone

2 Prehistoric axe-head

3 Roman Hoard

4 The Lunt Fort, Baginton

5 Benedictine abbess and nun

6 Saxon church with relic beam

7 Cnut presenting cross

8 Coventry Priory remains

9 Godiva and Leofric

10 `Godiva Window’, Holy Trinity

11 The Lady Godiva

12 High altar at Canterbury

13 Seal of Roger Longespee

14 Wells Cathedral

15 Seal of Richard Peche

16 Seal of Roger Northburgh

17 Street Plan of 1923, detail

18 Caesar’s Tower

19 Saxons ploughing

20 Hospital of St John

21 Monks chanting

22 Pilgrims

23 Priory guesthouse

24 Pilgrim badges

25 New Street

26 Holy Trinity in 1841

27 Coventry in the 14th century

28 Church of St John the Baptist

29 Whitefriars Monastery

30 Whitefriars Gate

31 Bachelor’s Gate

32 The Charterhouse

33 Carthusian monk

34 John of Eltham

35 Greyfriars Gate

36 Gosford Gate

37 Swanswell Gate

38 Hill Street Gate

39 Priory or Swanswell Gate

40 Cook Street Gate

41 Mill Lane Gate

42 Street Plan of 1923

43 Fourteenth-century joust

44 Edward the Black Prince

45 Sir William Bagot

46 St Mary’s Hall

47 St Mary’s Hall medieval kitchen

48 St George’s Chapel

49 Henry VI and John Talbot

50 Cardinal Beaufort

51 Henry VI in St Michael’s

52 John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury

53 Margaret of Anjou

54 Earl of Warwick

55 Meeting in a Chapter House

56 The Golden Cross in Hay Lane

57 A Coventry silver groat

58 Cheylesmore Manor gatehouse

59 Fourteenth-century friar

60 The church of St Michael

61 Carving of St Michael

62 The Knaves or whipping post

63 Butcher Row and the Bull Ring

64 A merchant’s shop

65 Henry VII

66 Fifteenth-century execution

67 King’s Window, St Mary’s Hall

68 The Coventry Tapestry

69 Henry VI on Tapestry

70 Margaret of Anjou on Tapestry

71 Drawing of walled Coventry

72 Burning Lawrence Saunders

73 Henry VIII

74 Greyfriars’ graveyard excavations

75 Franciscan friar

76 Benedictine monk

77 Carthusian monk

78 Carmelite friar

79 Priory surrender document seal

80 Remains of the Priory

81 Priory excavations

82 Encaustic tiles from the Priory

83 Carved head, Priory remains

84 Dorter undercroft, Priory

85 Excavations of the undercroft

86 State chair, St Mary’s Hall

87 Remains of Priory mill, 1930s

88 Pageant wagon in Broadgate

89 Coventry Cross

90 Elizabeth I

91 Mary Queen of Scots

92 John Hales

93 The Free Grammar School

94 The Guildhall, Bayley Lane

95 Stocks by St Mary’s Hall

96 Courtyard of Ford’s Hospital

97 Old Malt House, Gosford Street

98 William Shakespeare

99 James I

100 Palace Yard, Earl Street

101 Sir John Harington

102 Princess Elizabeth

103 The Coventry Cup

104 St Mary’s Guildhall entrance

105 Coventry in 1610 by John Speed

106 Prospect of walled Coventry

107 Charles I

108 Civil War re-enactment

109 Robert Greville, Lord Brooke

110 Spencer Compton

111 Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

112 Prince Rupert of the Rhine

113 Spon Gate

114 Basil Fielding, Earl of Denbigh

115 Church of St John the Baptist

116 Colonel William Purefoy

117 James, Duke of Monmouth

118 James II

119 St John’s in the 19th century

120 Remains of the west tower

121 Richard Baxter

122 Cook Street Gate

123 Philemon Holland

124 Free Grammar School

125 Home of Orlando Bridgeman M.P.

126 Broadgate, west side

127 Map of Coventry 1748

128 Girls of the Blue Coat School

129 The Blue Coat School

130 Much Park Street

131 St Michael’s church

132 Mayor’s Parlour, Cross Cheaping

133 Execution broadside

134 The market place

135 Great Hall, St Mary’s Hall

136 Grave of John Parkes

137 Miss Sarah Siddons

138 Coventry Barracks

139 View of Coventry in 1809

140 Whitefriars workhouse

141 Whitefriars cloisters

142 Cross Cheaping and the Burges

143 Cross Cheaping and Broadgate

144 Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital

145 Broadgate in 1898

146 Hales Street in the 1890s

147 Coventry railway station

148 The Royal Field Artillery

149 Coventry election, 1865

150 By Order of the Mayor

151 Weavers’ soup kitchen

152 Thomas Stevens ribbon

153 Watches made by A.H. Read

154 Rotherham’s in Spon Street

155 Thomas Chapman, watchmaker

156 Singer cycle advert, 1886

157 Advert for `Rover’ safety cycle

158 Early motor vehicles

159 Schoolyard and Hospital

160 Bayley’s Blue Gift Charity School

161 Horse-racing in 1845

162 George Eliot

163 View of Coventry, c.1838

164 Death mask of Mary Ball

165 The stocks and the Watch House

166 St Michael’s in 1841

167 Choir and apse of St Michael’s

168 Greyfriars rebuilt as Christchurch

169 St Osburg’s Catholic Church

170 Opening of Coventry Fire Station

171 Barrs Hill Girls School

172 Broadgate in 1929

173 Broadgate and High Street, 1926

174 Humber and Hillman cars

175 Whitley bombers at Baginton

176 Ordnance Works in Red Lane

177 Hertford Street ablaze, 1940

178 Eagle Street, 15 November 1940

179 Mass burial after blitz

180 Coventry Cathedral ruins

181 Corporation Street redevelopment

182 King and Queen look at plans

183 The Phoenix Levelling Stone

184 Gibson’s plan for the precinct

185 City centre cleared of rubble

186 Princess Elizabeth

187 Building the Upper Precinct

188 The Upper Precinct in 1955

189 Market Way and Smithford Way

190 Broadgate in 2001

191 The Godiva statue in 1978

192 Coventry’s new Cathedral

193 Consecration of the Cathedral

194 Graham Sutherland tapestry

195 The Upper Precinct in 2001

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to the British Museum, British Library and the Public Record Office for their help. Also many thanks for the continuing help of Coventry City Libraries, Local Studies Section and Coventry City Archives, and particular thanks to Simon Thraves of Phillimore for his hard work in the production of the book. I would also like to thank all of Coventry’s previous antiquarians and historians over the centuries who have all contributed in some way to this work. The sources for this work have been gathered over many years and are too numerous to name.

Most illustrations are from my own collection, but those I would like to thank for illustrations are Coventry City Council, Coventry Libraries, Local Studies, COVENTRY EVENING TELEGRAPH, Midland Air Museum, John Ashby, Margaret Rylatt, Barry Denton, Les Fannon, Albert Peck, Cliff Barlow, Trevor Pring, Frank Scotland, Joseph York, Roy Baron, Jane Railton, Neil Cowley, Roger Bailey, David Morgan, Kathleen and Susan Spragg and Craig Taylor.

One

BEGINNINGS

PREHISTORY

Warwickshire’s earliest known rock deposit lies north of Coventry in the Nuneaton area. It dates to the Pre-Cambrian period and consists of volcanic ash laid down some 600 million years ago. In the Cambrian period the land was swamped by a sea, which began to recede in the Devonian era (408 - 360 million years ago), the north of the county becoming river deltas. The rock laid down in this period is well known in Coventry and the county as the traditional building material, old red sandstone.

In the Carboniferous period (360 - 286 million years ago) Coventry lay within an area of deltaic mudflats and swamp forest, thick with trees and ferns. The crushed remnants of this once great forest were burned in local fires as coal, mined from the 17th century at such places as Wyken, Walsgrave, Binley and Keresley.

As the Carboniferous moved into the Permian period the swamp forest disappeared. The Coventry area was peaceful compared with the north of the county, which suffered from earthquakes. Paddling about in the warm waters of the local lagoons were creatures such as the carnivorous, armour-plated amphibian, Dasyceps bucklandi. This species was local to Warwickshire. In the age of the dinosaur, the whole of the county was covered by a warm shallow sea teeming with life such as fish, ammonites, belamites and dinosaurs, such as the long-necked, four-paddled Plesiosaur and the dolphin-like Ichthyosaur. Fine examples of both have been unearthed in the south of the county, and `a fine head, much compressed, and a large jaw with teeth’ of a Mastodontosaurus was found in Keuper beds in Coventry.

Sixty-five million years ago the sea retreated and the area became temperate, interrupted by three glacial periods and a period dominated by a sub-tropical climate. In the centre of Coventry, on the old Alvis site on the Holyhead Road, a hippopotamus skull was unearthed some years ago. During the glacial period Coventry and part of Warwickshire was covered by Glacial Lake Harrison,1 the ice from which helped form the landscape we see today.

Just outside Coventry lies the small village of Bubbenhall, where in recent years evidence has been found of early man. At the site of Waverly Wood Quarry archaeologists have unearthed flaked tools and enormous hand axes which were once wielded by Homo Erectus. These have been amino-acid dated and found to be 500,000 years old.2 Animal remains show that their owners were following the great herds as they migrated across ancient Warwickshire. The site is one of the oldest known in England. Another ancient site on the outskirts of the city is Baginton, where finds from the Lower Palaeolithic have been made,3 such as a rare quartzite hand axe and flint implements, as well as microliths dating back to the Mesolithic period. These have also been found on the northern edge of the city at what appears to be a seasonal camp on Corley Rocks, Corley. As far back as 1935 there were 23 known sites around Coventry which had turned up worked flint tools.4 It is also worth noting three worked flints, consisting of a possible arrowhead, a scraper and possible flint knife, found during excavations at the Charterhouse. All the tools were found out of context, which indicates early prehistoric passage, probably along the river through Coventry centre.5

Another ancient site, this time within the present city boundary, is the area occupied by Gibbet Hill and part of Warwick University. The area appears to have had almost continuous occupation since the Neolithic period. Amongst the many local finds are stone axes made at the `axe factory’ at Craig Llwyd in North Wales.6 Recently Iron-Age roundhouses were discovered here. In 1968 a stone butted axe made in the Penzance region was found in the Allesley/Eastern Green area, and an axe made in the Lake District was found at Corley, which leads some experts to believe the Coventry district lay on a prehistoric trade route. A comptonite hammer-axe made in the Griff area near Nuneaton was found in 1968 in a garden in Greendale Road, only one and a half miles from the Penzance axe.7

The Neolithic peoples were the first to introduce agriculture, living in settled communities and not following the herds. Wherever they lived can usually be found burial mounds. Few are known in the Coventry area, but sources do tell of lost undated mounds,8 such as the Giants Grave which could once be found in Hillfields and two undated tumuli in the grounds of Coombe Abbey.9 This mound could date to the Bronze Age, however, like the two round barrows recorded at Baginton. These were built by the `Beaker People’, one of whose clay `beakers’ was destroyed in the Coventry Reference Library on 14 November 1940. Likewise, the `Brandon Barrow’ in the Brandon area on the edge of the city was destroyed when the branch railway station was built. At Walsgrave-on-Sow in 1882 a finely polished greenstone socketed axe-head was found,10 which could date from the Mesolithic to the early Bronze Age.

The camp at Corley Rocks was excavated in 1923 and is believed to have been occasionally occupied from the Neolithic to the Roman period. It has been suggested in the past that Barrs Hill in Radford was at some point a prehistoric camp. Clues to this lie in the pre-16th-century local name of Medelborowe or `middle-borough’, borough or burgh signifying a fortified place. It has also been noted that in prints of the area made in the 18th century terracing can be seen on the hillside. This may have been made in the Civil War period, when the area was occupied for a short time as an `outer’ fortification of the city, but the old ditch fortifications could simply have been re-dug. The PROCEEDINGS OF THE WARWICKSHIRE NATURALIST AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY of 1904, in a report on prehistoric covered ways, notes the following: `Barrs Hill, Coventry, 200 yards, down to Radford Brook. This way has long been filled up.’ The sunken track ran down the hill towards Middleborough Road and was wide enough to take one man and one animal walking side by side, in the tradition of all such ancient fort tracks, so that people could use them unseen by enemies, or to escape or outflank attackers. It cannot be linked to any Civil War fortification for it runs not towards the city but away from it. The existence of the track adds weight to the belief that the hill was indeed a prehistoric fortification.

1 THE ONLY KNOWN PICTURE OF A TUMULI AND STANDING STONE IN THE COVENTRY AREA, COOMBE ABBEY, 1729.

Very little from the Celtic/Bronze-Age period has been found around Coventry, though enough to suggest the passage of people through the area. Broadgate Hill, its original name unknown, is surrounded by a massive ditch which the Saxons called the `Hyrsum Ditch’, the ditch of obedience, which stretches from above Earl Street around the hill-top probably down to Pool Meadow; this lower end was probably the `rather wide stagnant ditch’ mentioned in 1910 in the COVENTRY STANDARD.11 It may have formed a barrier to keep people out, or it may have been created to demark a sacred site. It may, of course, date to the later Saxon period and be some sort of town ditch or part of a burh, a fortified enclosure. The Hyrsum has been archaeologically dated to the 12th century, by odd pottery fragments, but it bears a Saxon name and may have been re-dug because of silting in the 12th century, probably during the war between Stephen and Matilda.

On and around Broadgate Hill, the centre of this enclosure, odd finds have been made, such as a hollowed-out log boat and coracle paddle. The valley formed by Broadgate and Barrs Hill was originally a huge lake, which fluctuated in size according to the seasons, known as the Bablake or `Babbu-lacu’. A remnant was known in the 14th century as the `Babylake’. An explanation for the name is that it was a stream (some have suggested `lacu’ means stream) associated with someone called Babban, i.e. Babban’s stream. This seems unlikely considering that what filled the valley was a large lake stretching from beyond Queen Victoria Road to Market Way to Pool Meadow. This lake has in places left up to thirty feet of silt. When the Woolworth store was being constructed in the early 1950s it was noted that hundreds of oak piles protuded from the lake bed. No proper excavation was done on the site so we can only guess at their possible origins. Much of this ground was still undeveloped as late as 1807.12

During the rebuilding of Broadgate in 1947 a workman unearthed a Bronze-Age axe-head, which was displayed but later disappeared. However, a photograph13 of objects found in Broadgate showed various items from different periods, amongst them the coracle paddle and axe, as well as a socketed and looped palstave dating from between 850 and 650 B.C. A second axe-head of the same type was found in a field at Canley amongst spoil taken from Broadgate during the same excavations. As late as the 1960s the find was dismissed as an unrecorded axe-head blasted a considerable distance from a `former museum, bombed during the war, [which] stood near this area’.14 The museum referred to, John Shelton’s Benedictine Museum in Little Park Street. Shelton had saved his collection of artefacts from his home, which was burned but not blown up. It seems clear that this second axe originated in Broadgate. Now, one axe could be a casual loss, but two is unlikely. A founder’s hoard of damaged implements for re-smelting is also unlikely, as the axes were intact, which leaves the possibility of deliberate burial as an offering on a sacred hill-top, a practice not uncommon in the period we are dealing with. Sadly, during the period when Broadgate was being dug up much evidence of Coventry’s early history was destroyed.

There was a third Bronze-Age axe-head from Coventry in the Staunton Collection, said to have been used in the old Coventry Pageants or found on the site of one of the pageant houses. Another axe-head found on Whitley Aerodrome in 1928 has been dated to 1500 B.C.,15 and a Gallo-Belgic gold stater dating from 57 to 45 B.C. was found in a garden in Beake Avenue, Radford. WEST MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY (35, 1992) reported the discovery of the end link of a decorative bronze bridle bit, dating from the late 1st century B.C. to the early 1st century A.D., found by a metal detectorist in the Coundon area.

During the period known as the Iron Age, Warwickshire lay in the borderlands of the Coritani, to the north-east, the Cornovii in the west and the Iceni in the east. Celtic names survive in local rivers such as the `Abhain’, for Avon, `Leamh’ for Leam, and Sowe, known by the Celts as the `Samhadh’. The main watercourses running into the centre of Coventry are the Radford Brook and the Sherbourne. The Radford Brook has lost its original name but the Sherbourne derives from the Anglo-Saxon and is translated `shere-bourne’, meaning `clear stream’. It does, however, appear to have an older name, the `Cune’. The ancient Cune/Sherebourne passes through Coundon (Cunehealm), giving the Celtic settlement its name.

2 PREHISTORIC AXE-HEAD FOUND IN BROADGATE IN 1947. (DRAWING BY DAVID MCGRORY)

The word `cune’ (sometimes spelt `couen’ or `couaen’) can be found in Couaentree, the earliest spelling of Coventry in Edward the Confessor’s charter confirming the foundation of Coventry monastery.16 This has been suggested by many historians as the origin of the Coventry place-name, the `treabh’ element indicating a farmed village on the Cune. The word `cune’ can also be linked to a meeting place of two water sources, such as at Cound near Shrewsbury, where the `Cound’ meets the Severn. Mildenhall in Wiltshire, where the Og meets the Kennet, was known in Romano-British times as Cunetio.17 It is notable that the Celtic god Condatis gave his name to watersmeets and confluences. Coventry itself had its own meeting place of the waters: the Cune/Sherbourne flowed into the Radford Brook (possibly known as the Cunnet) at the bottom of present-day Trinity Street, where the Mill Dam was. Both watercourses would have fed the great Bablake. The name Cune seems to have been known locally until at least the 16th century and appears to have two meanings in the Celtic language, either `hound’ or, from `kuno’, `the exalted holy river’. The Anglo-Saxon `shere-bourne’ can be interpreted as sacred or pure river, and it is known that the Celts considered many rivers sacred, especially those, like the Cune/Sherbourne, rising from the earth.

Other former suggestions for `Coventre’ are the `convent town’ or the `covenant tree’, indicating a tree by which a covenant or pact was made between two Danish warriors. Both these have long since been dismissed, a place-name expert in the late 1890s, after many years of confusion, deriving the city’s name from a word used in a copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dated about 1060. `Cofantreo’18 is used only once and is translated, ignoring the `n’, as the tree of Cofa. But there appears to be no known Anglo-Saxon personal name `Cofa’, the nearest being `Cufa’.19 And `cofa’ is only ever used as part of another word, to mean `heart’. The Anglo-Saxon pronunciation of the word `Cofantreo’ would be Covantreo, the Saxon `v’ always being written as an `f’, another example being `Beferburna’ pronounced Beverburna, the Bever stream. If Cofa did not exist, and the actual word is `Cofan’/`Cofen’, pronounced Covan/Coven, we have a known Early English word meaning a cave, valley or cell.20 The site of old Coventry lay on the side of a valley which has a tradition of a cave in its hillside. In the OXFORD DICTIONARY OF ENGLISH PLACE NAMES, `Coven’ is said to mean a valley among the hills, again fitting for Coventry’s location.

ROMAN COVENTRY

It used to be though that there was no evidence of a Roman presence in what came to be Coventry. It is now safe to say that the Roman’s knew the place and also inhabited here.

Traditionally, Julius Agricola passed through Coventry, built a marching camp on Barrs Hill and called the nearby settlement `Coventina’. Barrs Hill did bear marks of undated fortification, and Roman coins and pottery dating from the reign of Tiberius (A.D.14) to the 4th century have in the past been found upon the hill. Also, at the base of Barrs Hill, Shelton unearthed a wooden causeway 15 feet across built on oak piles driven into the bed of the Babbu-lacu. He declared the work Roman, and to corroborate his theory he also found Roman horseshoes on the bankside near to present Well Street. The structure suggests trained builders, and Agricola’s Legio XX (which left Britain A.D.87) are known to have passed through the area. They were engineers and quite capable of constructing a causeway. During building they would have camped on the high ground above the valley, i.e. Barrs or Broadgate Hill.

As for Coventina, there is a shrine dedicated to this Romano-Celtic goddess at the legionary fort at Crawborough in Yorkshire. The goddess, who is part of a water cult, was normally shown naked or semi-naked pouring water from an urn and holding a plant. In the 19th century a `medal’ was found during building work in New Buildings, said to have on one side a woman pouring water from a jug and on the other a naked woman with a plant between her feet. The fact that the medal, now lost, bore a nude woman suggests it was Roman rather than later. At Crawborough, the shrine to the goddess consisted of a decorated altar before a walled pool in which offerings were made. One such pool existed at the bottom of Cox Street and was known as Hob’s Hole. Hob, of course, is a name connected with the devil, so the previously sacred paved pool became the devil’s hole in Christian times.

In the Sherbourne in Cox Street, near to the hole, Shelton excavated the original riverbed and found `a coin of Emperor Galinus (A.D. 253-88), a bronze ring, jet ring, toilet set for nails and ears, surgeons needles, pottery, iron handles, bronze for beating out, shears, etc’.21 These were sent to the British Museum and the smaller objects were identified as `the contents of a Roman lady’s satchel’. This find is significant inasmuch as it shows Coventry lay not in a wilderness familiar only to legionaries but on an established route which Roman women travelled along.

It is thought that two Roman routes met at Coventry, one or both of which may be of prehistoric origin. One of these began from Mancetter (Manduessedum) by the Roman Watling Street (A5). Mancetter was the site of a Roman settlement and legionary fort, and the site of the `Field of Chariots’ where Boudicca’s revolt against Roman rule was crushed in A.D.61. It is believed that the horses captured after this event were trained by the Romans in the rare horse-gyrus at the Lunt, Baginton. The road passes Caldecote Hill, Caldecote being a name regularly found on Roman roads, then the Roman pottery kilns at Hartshill, and the Roman camp at Camp Hill. It emerges on the other side of Nuneaton at Caldwell as the present-day B4113. Here we have again the occurrence of `Cald’, which is thought to have indicated some sort of Roman roadside shelter. The road continues through Griff, where stone axes were made, possibly indicating a pre-Roman route, and Bedworth, site of Roman finds and a Roman trackway noted in 1793, and into Coventry through Longford, another name linked with Roman roads.22

3 HALF OF THE ROMAN HOARD FOUND IN FOLESHILL. (Gentleman’s Magazine)

The road then continues either along the course of the present Foleshill Road or joins a secondary route following that of the Stoney Stanton Road. Near the bottom of this route in 1792 a large and significant Roman find was made. It was reported in the COVENTRY MERCURY:

On the 17th of December last, was discovered in a meadow at Foleshill, belonging to Mr. Jos. Whiting of that place, in digging a trench, about two feet below the surface, an earthen pot, containing upwards of 1,800 Roman copper coins, principally of the Emperors Constantine, Constans, Constantius and Magentius; most of which remain in the possession of Mr. Whiting, for the inspection of the curious. And on Sunday last, in continuing the same trench, he found another earthen jug, containing a greater quantity of larger coin; but the latter are in greater preservation.23

In the GENTLEMAN’S MAGAZINE of 1793, a correspondent signing himself `Explorator’ added that a `second pot was much broken when discovered, but appears from the fragments to resemble the former, only is smaller; the coins, though said to be better preserved, and larger, were precisely the same sorts, &c., as those first discovered.’24 This intriguing hoard of over 3,500 coins was found at Bullester Fields Farm and adds weight to the evidence that a Roman road ran through the site of present-day Coventry.

The track then cut in a westerly direction across the edge of Barrs Hill, in the direction of either Bishop Street or Cook Street and Silver Street, to the lake edge and the site of Shelton’s hippo-sandals and causeway. By this site ancient pillars `of great strength and size’ were also unearthed, and in 1796 another now forgotten object, an alabaster statuette of a warrior wearing a laurel crown was found. The figure was reported as being `considerably below the surface of Bishop Street and near to the Free School there’. The statuette, now lost, was believed to be Roman.

The Warwickshire Natural History and Archaeological Society reported (1868) that in 1820, near the bottom of Broadgate Hill, underneath a medieval cellar, was unearthed an `old pavement, said to be Roman’. This continued up to the top of Broadgate Hill, for it was here that the GENTLEMAN’S MAGAZINE of 1793 reports:

In the last summer the street in Coventry, called Broadgate, was opened to a depth of 5 or 6 feet, when a regular pavement was discovered, and upon that pavement, a coin of Nero in middle brass ...25

This find has been dismissed because it is known that a pavement was laid in Broadgate in medieval times, but other finds were made in the area. Shelton unearthed a stone trackway behind the Burges in the 1930s, and around the mid-19th century, workmen unearthed a 10-inch-high marble statue of Mars while digging behind Cross Cheaping. The statue shows one of the legions’ most favoured gods leaning against a shield and holding a wheatsheaf in his dual role as god of war and of agriculture. In Cross Cheaping, in the direction of the Broadgate track, a Roman `pavement’ was discovered at the end of the 19th century.26 The coin of Nero was not the only one to be found on Broadgate Hill. Nineteenth-century historian William G. Fretton wrote, `I have several Roman coins found in this locality’.27 In the Municipal Exhibition at the Drill Hall in 1945, wooden water pipes, found in Broadgate and believed to be Roman, were exhibited.

Other finds from the Coventry district include a possible villa or farmstead site unearthed during the building of the Showcase Cinema in Walsgrave.28 The area lies below Mount Pleasant, another place-name linked to Roman sites. During a recent dig (1999) in Gosford Street a Roman fibulae brooch was unearthed. A third-century Roman coin, an antoninianus probably of Constantius or Constantine, was unearthed during excavations in Much Park Street in 1970-4.29 Roman pottery was unearthed in Spon Street in 1976 and coins of emperors such as Antoninus Pius, Gordian, Maximian, Julian and others have been found in Keresley, Radford, Coundon, Whoberley and Stoke. In 1912 a Roman pot in coarse grey-ware was unearthed in Broad Lane. Fragments of Roman pottery were discovered in nearby Broomfield Road,30 and more Roman pottery was found near Centaur Road.

The Lunt Roman Fort, already mentioned, was first set up, it is thought, at the time of the Boudiccan revolt as a legionary headquarters and then a training camp for captured Iceni horses. It was built on a spur of land overlooking the River Sowe. Its name originally meant `wooded slope’. Roman occupation at Baginton was unknown until 1928, when Edwards and Shotton discovered two rubbish pits which contained pottery. By 1959 the Roman site was believed to have consisted of a farm or villa.31 But this was to change when excavations began in 1960 and defensive ditches were unearthed, quickly followed by evidence of a large fort. A settlement appears to have been built up around it, stretching towards the present airport.

The fort continued to grow until A.D.80 when it was abandoned, probably because Julius Agricola needed the troops for his northern campaign. The legions returned in the reign of Galinus (A.D.253-88)32 and rebuilt a fortification, and the present gateway and ditches date from this period. The gate was dated by a coin of Galinus found in a post-hole. The coin was believed to have been lost, but it is more likely that the gate builders deliberately placed it in the post-hole as a protective offering. A piece of late third-century Wappenbury grey-ware was also unearthed from a ditch.33

The gyrus (circular training ring) from the first fort, which has been re-constructed, is unparalleled in western Europe. It measures some 107 feet around and the `archaeological evidence strongly suggests’34 that it is a cavalry training ring. Here horses could be conditioned for battle by men positioned around the ring striking their swords against their shields. The sounds mimicked those of battle. The original fort also contained granaries (HORREA), headquarters (PRINCIPA), commander’s house (PRAETORIUM), workshops (FABRICA), stables and barracks (in the Praetentura). The fort may have originated as a training camp for captured horse, but up until A.D.80 it probably developed as a specialist training centre for elite cavalry such as the COHORS EQUITATA.

4 THE RARE GYRUS AT THE LUNT FORT, BAGINTON. (MARGARET RYLATT/COVENTRY CITY COUNCIL)

SAXON COVENTRY AND OSBURGA

After the fall of Roman Britain the Romano-British population absorbed Anglo-Saxon immigrants who were well established in the area by the mid-sixth century. The famed Baginton Bowl, a large bronze and silver, enamelled and jewelled bowl, was unearthed at a large burial ground. Many fresh settlements sprang up, as the word `ley’ for `forest clearing’ testifies. These include Keresley, Allesley, Henley, Whitley, Binley, Canley, and Whoberley. Others now lost include Shortley, Bissesley and Pinley.

As for the central settlement in Coventry, we can only make assumptions. No buildings have been found, although this does not mean they did not exist. Dugdale believed the earliest settlement lay on Barrs Hill. Later historians mention that undated coins and old stonework were unearthed here, and tradition tells us that the missionary St Chad passed through the area (there was a St Chad’s Well in Stoke) and built a small chapel on Barrs Hill. It is true that Barrs Hill was once the home of a church dedicated to St Nicholas, a dedication which points to an early building. By the Dissolution this chapel had grown into a large church, consisting of a central chancel with towers and spires on both ends, which fact was later remembered in the field names of `big’ and `little spire field.’

Central England at this time was not a Christian place; it was not until 655 that the heathen king of Mercia, Penda, was killed in battle. His son Paeda, who became a Christian, succeeded him. A year later he was succeeded by Wulphere (656-75), who in 661 allowed the first baptisms in Hwiccia (south Mercia). Although some of the Saxon nobility adopted the faith and allowed the construction of churches, Christianity was less widespread among the rural population. Various edicts throughout the Saxon and into the medieval period outlawed the veneration of trees, rocks and springs.

Osburga (commonly known as Osburg), meaning `divine fortress’, was one of the famed sisters of the Saxon monastic house at Barking. An obscure figure, she is mentioned only once in her lifetime by St Aldhelm, Bishop of Sherborne (died 709). His book DE LAUDIBUS VIRGINITATIS, written around 675, was dedicated to the `Sisterhood of Barking’ and records that Osburga and the other sisters of the house left Barking to establish monastic settlements elsewhere. Tradition, the later existence of St Osburg’s Pool and the fact that her relics lay in Coventry strongly suggest that Osburga came to Coventry as abbess around the year 700. An anonymous 14th-century manuscript in the Bodleian Library also informs us that, `In ancient times on the bank of the river called by the inhabitants Sherbourne, which flows right through the city of Coventry, there was formerly a monastery of maidens dedicated to God.’35

The monastery would most likely have been a double house holding both monks and nuns and ruled over by an abbess. This was the norm during the seventh and eighth centuries, the church in this period having no wish for seclusion since the suppression of paganism could not be conducted from behind closed doors. Many Christian churches were built directly upon pre-Christian sacred sites, which may explain why Osburga decided to build upon Broadgate Hill. After her death the house was dedicated in her name and her relics displayed in a reliquary on a large crossbeam.

The monastic house continued to serve the local area through troubled times. In the year 829 Ecgbryth `overcame the Mercian kingdom’, and in 910 the land of the Mercians was `ravaged’. Archaeologist Mick Aston has suggested that monasticism was `virtually extinguished’ in this period. But most of the Danes that settled in England were massacred on St Brice’s Day, 13 November 1002, including those in Coventry, and for some time afterwards Coventry became famous for its Hock Tuesday play, which acted out the massacre. Sixteenth-century historian Robert Laneham says of the play that it was `wont to be play’d in the citie yearly’.

5 A BENEDICTINE ABBESS AND NUN (19TH-CENTURY ENGRAVING).

6 RECONSTRUCTION OF A SEVENTH/EIGHTH-CENTURY SAXON CHURCH WITH RELIC BEAM (19TH-CENTURY ENGRAVING).

When Alfred the Great had forced the Danes to agree to the `Peace of Wedmore’ in 878, which confined them to the Danelaw, an area north of Watling Street, it was said that `much of Mercia was practically in ruins, cities and monasteries had to be rebuilt’. Reminders of the Danes in this area, probably infiltration from the Danelaw, are place-names such as `Biggin’ (Stoke), which is Danish for house, and Keresley, which means `Kaerers clearing’. Another relic dating to around this period is an axe believed to be Danish in style.

It is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles of the year 1016, that `In this year came Cnut with his host, and with him ealdorman Eadric, and crossed the Thames into Mercia at Cricklade, and then during the season of Christmas turned into Warwickshire, and harried and burned and slew all that they found.’ This Danish army was led through the county by one who knew it well, Edric Streona, known to history as Edric the Traitor or Grasper. Cnut took the land by force and was crowned king of all except Wessex. John Rous, the 15th-century priest and antiquarian who lived at the hermitage at Guys Cliff, must have had access to ancient documents for he wrote of the destruction of the Hom Hill fortress at Stoneleigh and added, `even the Abbey of Nuns at Coventry is destroyed, of which in times past the Virgin St Osburg was the Abbess’.36 The Danes probably burned down St Osburga’s, but some of her bones and her skull survived and were later re-housed in new reliquaries.

7 CNUT PRESENTS A CROSS TO A NEWLY RESTORED CHURCH (19TH-CENTURY ENGRAVING).

By all accounts Cnut ruled well. At the Council of Oxford in 1018 he agreed to rule under `one God’ and to avoid `heathen practices’. He grew remorseful for the blood he had shed and the destruction he had caused in taking the throne, and in 1026 he went to Rome. From here in April 1027 he wrote a letter to his people, saying amongst other things that `I have vowed to God himself, henceforth to reform my life in all things ... and with God’s assistance, to rectify anything hitherto unjustly done.’37 Amongst these rectifications was the rebuilding of many religious houses that his army had previously destroyed. William of Malmesbury says that, `He repaired throughout England, the monasteries which had been partly injured and partly destroyed by the military incursions of himself or his father; he built churches in all the places he had fought.’ The 16th-century antiquarian John Leland, quoting old sources, states that the site of Coventry Priory was formerly the place where `Kynge Canute the Dane made [a] howse of nunes. Leofrike, Erle of the Marches, turnyd it in Kyng Edward the Confessor’s dayes into a howes of monkes.’

The house of nuns that Cnut `made’ must refer to the rebuilding or restoration of St Osburga’s. A piece of local red sandstone, decorated with a squirrel in a tree or vine, unearthed in Palmer Lane in 1934 was until quite recently believed to be a piece of a cross but has now been identified as a door jamb which may have formed part of the entrance to the church itself. Another relic of Osburga was found during the excavations of the west entrance of Coventry Priory in 1868, when a letter appeared in the COVENTRY HERALD stating, `Sir, it gives me intense gratitude to behold with my own eyes … the very seal of Coventry’s ancient Minister, now in the possession of Mr Hinds, the druggist of Far Gosford Street. It is fine cut-stone … the usual size of a conventual Abbey Seal, with the rude figure of St. Osburg upon it, standing up with a Crozier in her left hand … Mr. Odell, a kind Magistrate of this city, informed me that this sacred relic, which has St. Osburg’s name upon it and figure, was found amidst the rubbish while it was being carted away from the excavations then being made for the present Blue Coat School.’38

8 THE WEST ENTRANCE TO COVENTRY PRIORY IN THE 1950S. THE COLUMNS WERE ORIGINALLY PAINTED RED AND WHITE.

St Osburga’s `restored’ church would obviously have housed the relics of Osburga herself. Cnut also gave to the `church of Coventry’ another important relic, namely the arm of St Augustine of Hippo, `the Great Doctor’. It appears that in 1022 he ordered Archbishop Aethelnoth to purchase the arm in Pavia for a 100 talents of silver and one talent of gold. The relic was presented to the rebuilt/restored church and Cnut was a step nearer to heaven; such a gift `would gain him many friends and prayers’.39

Leland and Sir William Dugdale both state that Leofric created the house in the reign of Edward the Confessor and the date of foundation fits this, 1043 being the year that Edward was crowned. But the 1043 date belongs to a confirmation charter and not the original. It is likely, however, that this confirmation was produced around the same time as the dedication. Dugdale quotes a manuscript written by a later prior, Galfridus (1216-36), who categorically states that Archbishop Edsie performed the ceremony on 4 October 1043 in the presence of Abbot Leofwine (no other abbots are recorded before him) and 24 monks, and this foundation was also confirmed by a papal BULLA, although it later proved to be a forgery. It could be a complete fabrication or the replacement for a lost document.

Recent (1999-2001) archaeological excavations on the site of St Mary’s Priory have produced a spectacular find under the north chancel, near No. 7 Priory Row. Stone and skeletal remains IN SITU suggest that St Osburga’s stood on this site. The curved stonework discovered could reflect the fact that many seventh- and eighth-century Saxon churches had semi-circular apses, even though it is facing north. During the dig a large enclosing ditch was unearthed which had been filled in in the 12th century and may be a defensive or boundary enclosure in the manner of other Saxon churches such as South Elmham in Suffolk. It may, however, date from the fortification of the monastery in the early 12th century by Earl Marmion.

Many early Saxon churches were enclosed or added to in later periods, and the fact that Leland suggests that Leofric turned the house of nuns into a house of monks may infer the swallowing up or extending of the old church with a rebuilding and refoundation under the Benedictine rule. Certainly the monastery of St Mary was also dedicated to St Osburga. The site already had a river and pool, and springs such as the one which fed the Priory’s main water source, the Broad Well, also existed.

LEOFRIC, GODIVA AND AELFGAR

Leofric, Earl of Mercia, or, to give him his original title, Leofric, `hlaford Myrcena’ (Lord of the Mercians), was the son of Leofwine, ealdorman of the Hwicce (south Mercia) in 997.40 Leofwine retained the title even after Cnut had executed his eldest son (Leofric’s brother), Northman. Leofric was created Earl of Mercia by Cnut around 1026. His family gained their aristocratic status despite Cnut’s policy of replacing Danish earls with Saxons.

Florence of Worcester records that Cnut treated Leofric with `great kindness’ and Ingnulphus adds that the King `greatly loved Earl Leofric’. Leofric was also a friend and confidant of Edward the Confessor, supporting his right to the throne against the other great earl, the powerful Godwin. The tradition of Leofric as the `grim’ lord, a heartless tyrant who forced his wife to shame herself, is nonsense, and in his lifetime Leofric was considered a great man, a diplomat and a saint. He was extremely religious and attended mass twice a day.

It was expected in this time that all great men should use their wealth to build new churches and bestow land and other gifts upon them. Leofric founded (or re-founded) the great church in Coventry, and supported it with lands, and other churches across his great lordship from Evesham to Croyland in Lincolnshire. Other sides to his character were as soldier and peacemaker. When a revolt began in Worcester which threatened the stability of the throne, it is said Leofric nearly razed the town to the ground. As for the peacemaker, `It is difficult to tell of the distress and all the marching and the camping, and destruction of men and of horses, which all the English army endured until Leofric the Earl came thither, and Harold the Earl and Bishop Alder, and made a reconciliation there between them.’41

The man many considered an uncanonised saint, who had seen miraculous visions and raised Harold I, Harthacnut and Edward the Confessor to the throne, died in 1057 at his hall at Kings Bromley, Staffordshire. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle informs us that, `In this same year, on 30 October, earl Leofric passed away. He was very wise in all matters, both religious and secular, that benefited all this nation.’ He was brought from his hall in Staffordshire to be buried in great pomp at Coventry at his church of St Mary. Roger de Hoveden wrote that, `Leofric, that praiseworthy Earl of happy memory, son of Duke Leofwine, departed this life … and was honourably buried at Coventry.’ William of Malmesbury adds that Leofric’s body came with a huge donation of gold and silver and was lain within one of the porches of the church.

Godiva, whose name was really Godgifu, meaning `Gods Gift’, was the sister of Thorold, Sheriff of Lincolnshire. A charter concerning Croyland Abbey, quoted in the Chronicles of Ingnulphus, now believed to have been written in the 14th century, is our only source connecting Godgifu to Thorold, and its claims are not necessarily fabrications. The charter refers to Aelfgar as Leofric’s eldest son, which implies that he and Godiva had more than one. That second son has been linked with Hereward the Wake. The DE GESTIS HEREWARDI from 1150 states that Hereward was the son of Leofric of Bourne (near Croyland) and Ediva. Ingnulphus gives the same parentage and also connects Leofric with Croyland Abbey, which we know was connected to the family.

Two sources tell us that the Abbot of Peterborough was Leofric’s nephew and Hereward’s uncle.42 Hereward and his rebels certainly sacked the abbey after William the Conqueror had placed a Norman bishop in the building. Among the rebels was Earl Morcar, Leofric’s grandson and Hereward’s nephew. After the rebellion Hereward is said to have been reconciled to William and settled down with a gift of land. Domesday Book records that a Hereward held land in Warwickshire, Worcestershire and Lincolnshire, all part of the old kingdom of Mercia. Later sources such as the DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY dismiss the connection between Leofric and Hereward, but the most recent book on Hereward, published in 1995,43 goes into this issue in depth and in the end cannot dismiss its possibility.

9 VICTORIAN PAINTING OF GODIVA AND LEOFRIC.

There is also some debate about whether Godiva was even the sister of Thorold, again because of the dubious nature of many early charters. According to Burbidge, the relationship is confirmed by the CHRONICON PETROBURGENSE, where Thorold is described in Latin under the date 1050 as being vice count and brother of Godiva, countess. It is believed that Leofric was Godiva’s second husband, and that she split the land of her unnamed late husband (an earl) amongst the churches in the Ely area in the reign of Cnut. Possibly it was this same Godiva who is recorded in the LIBER ELIENSIS (chronicle of Ely Monastery) under the year 1022 as being in fear of death and giving more land (that of her late parents) to the monastery. It is not impossible that Godiva’s first husband was the incumbent of Mercia, the Danish Earl Eglaf, who died around this time during a visit to Constantinople.

Apart from references usually concerning occasional bestowal of land or gifts, Godiva is not mentioned in any chronicles of her time. She does, however, appear in chronicles written many years after her death. The 14th-century Croyland Chronicles of Ingnulphus refer to her as `the most beauteous of all women of her time’. Godiva’s love of the church is often mentioned, and especially her devotion to the Virgin Mary. The fact that she had once been near to death may have had a direct effect on her devotion. As well as building new churches and chapels, she made gifts of land and of other items such as jewels melted down and recast for holy relics. After Leofric’s death these became more modest. Her jewelled necklace was given to Coventry Abbey, and three cloaks, two curtains, two coverings for benches, two candlesticks and a book to Worcester Abbey. Godiva visited the abbey personally to make the gifts, `for the health of his [Leofric’s] and her soul’,44 and also because Leofric had taken lands off the abbey, promising their return after his death, and Godiva now wanted this extended until after her death.

Godiva was probably around 57 when Leofric died. Their son Aelfgar inherited the Mercian earldom and Godiva appears to have gone into retirement, supported by what remained of her lands. Some years later she may have gone into a religious house. She appears to have spent much time at the ancient Evesham Abbey, where she and Leofric built the church of Holy Trinity, and here she was buried. The Evesham Chroniclers claimed that Prior Aefic, her father confessor, had convinced Godiva to found a new Benedictine house for monks in Coventry.45 EVESHAM NOTES & QUERIES states that the last recorded visit of Godiva to Evesham was to attend the funeral of Prior Aefic at Holy Trinity. In his excellent book OLD COVENTRY AND LADY GODIVA, however, Dr Burbidge quotes this passage from the EAVESHAM CHRONICLE: `Then your worthy Prior Aefic departed from this daylight in the year of Our Lords Incarnation one thousand and thirty-eight, and his grave worthily exists in the same church of the Blessed Trinity near that of the same pious Countess Godiva, and of whom, so long as he lived, he was a friend.’ According to the `Douce Manuscript’ at Oxford, her date of death was 10 September 1067.

10 THE ‘GODIVA WINDOW’ OF HOLY TRINITY CHURCH.

So Godiva lived to see the death of her husband, the great Leofric of Mercia, and the death of her wayward son, Earl Aelfgar. She also witnessed her granddaughter Ealdgyth’s becoming Queen of England by marriage to King Harold, and the destruction of Saxon England with the death of Harold on Senlac Hill. Her estates were redistributed amongst various Norman lords.

THE LEGENDARY RIDE

Whether or not Godiva’s legendary naked ride through the market place of Coventry ever took place has been for centuries a source of debate. It was not written about in her lifetime, or the lifetimes of her children or grandchildren. In fact it wasn’t mentioned by any of the chroniclers until over 150 years after her death, which is probably because it never happened. The original story, probably told to Roger of Wendover in 1190 by monks displaced from Coventry Priory, appears in Wendover’s FLORES HISTORIARUM:

The Countess Godiva, who was a great lover of God’s Mother, longing to free the town of Coventry from heavy bondage from the oppression of a heavy toll, often with urgent prayers besought her husband, that from regard to Jesus Christ and his mother, he would free the town from that service, and all other heavy burdens.

The earl sharply rebuked her for foolishly asking what was so much to his damage, and always forbade her ever more to speak to him again on the subject. She, on the other hand, with a woman’s pertinacity, never ceased to exasperate her husband.

He at last gave her his answer: Mount your horse and ride naked, before all the people, through the market of the town, from one end to the other, and on your return, you shall have your request.

Godiva replied: But will you give me permission, if I am willing to do it? I will, said he. Whereupon the countess beloved of God, loosed her hair and let down her tresses, which covered the whole of her body, like a veil, and then mounting her horse and attended by two knights, she rode through the market-place, without being seen, except her fair legs.

Having completed the journey, she returned with gladness to her astonished husband, and obtained of him what she had asked for. Earl Leofric freed the town of Coventry and its inhabitants from the aforesaid service, and confirmed what he had done by charter.46

Wendover’s HISTORIARUM survives only as a 14th-century manuscript, so the above tale may not be the original. There are at least two other versions by Wendover, either written or revised by him or copied by others at Wendover’s scriptorium at St Albans, where he was a priest and later prior. In another account attributed to Wendover, Leofric isn’t `astonished’, but filled with admiration. A third account, most likely Wendover’s original, states that Godiva rode through the market seen by none and Leofric considered that a miracle had taken place. This miracle is repeated, and dated to the year 1057, in an account written by Matthew of Westminster (this may be Matthew Paris) which must have been copied from Wendover. It states that Godiva completed the ride and returned rejoicing to her husband, who considered it a miracle. In his own CHRONICA MAJORA, written in the early 13th century, Matthew Paris repeats the miracle: `hoc pro miraculo’.47

As these sources pre-date the 14th-century version above we can safely assume that we are dealing with a miracle. Godiva rode through the market place accompanied by two knights when it was full of people, and nobody saw her. It was a time of `miracles’, when the miraculous tales of the early chroniclers were known as `monkish tales’. This is the basis of the Godiva legend wherein the countess, benefactor of the people, is forced to take drastic steps to save `her’ people from a `burdensome servitude’.

The origins of the ride itself, regardless of Godiva’s participation or otherwise, may lie in ancient fertility rituals dating back to Romano-Celtic Britain. In the south of Warwickshire, about twenty miles from Coventry at Southam, which once belonged to Godiva, a `Godiva Procession’ survived until about 1845, which bore some aspects of a pagan rite. Two women on horseback, one white, one black, called `the Black and White Lady’, were completely covered with drapes of lace which made them virtually invisible to those looking upon them. It wasn’t always a case of blacking up, either, for in 1794 it was recorded that, `The inhabitants of that place have engaged a [real] Black Lady to accompany the celebrated Lady Godiva.’48 Leading the two women was another important character, a man wearing a bull mask called `brazen face’.

11 THE LADY GODIVA BY JULES LEFEBVRE, 1907.

The white woman represented one aspect of the fertility goddess, the black woman the darker side. The fact that the two were referred to as a single `lady’ suggests they were regarded as one. An illuminated document of the Smiths’ Company of Coventry shows Godiva followed by a black woman riding an elephant, and in one version of the `Banbury Cross’ rhyme we find, `Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross, to see a black lady ride on a white horse.’49

The man dressed as a bull was outlawed by the Church as late as the 7th century. The bull mask was symbolic of fertility, the `brazen face’ a symbol of the sun, the giver of life. Despite being outlawed, the `Ooser’ (as he was known) survived in rural England into the 20th century. This pre-Christian deity could be found in places such as Melbury Osmund in Dorset, where generations of the same family were guardians of the horned bull mask with bulging eyes. A bull mask was also used in Shillingston, Dorset in Christmas rituals with young girls.

It is known that fertility rites took place in the Romano-Celtic period wherein naked women blackened themselves with woad, one ancient ritual involving girls on horseback being led around the fields by a bull-masked man. In their original form they were believed to restore fertility to the land, and to give some assurance of good crops and healthy beasts. Such traditions can be traced back to the Neolithic period, when myths told of the earth-goddess being annually impregnated by her consort the sun-god, who then lost his power until the next fertility cycle.

The `Godiva Window’ which could once be seen in Holy Trinity Church depicted a woman, said to be Godiva, sitting side-saddle on a white horse in a yellow dress and holding in her hand a flowering hawthorn branch. The May tree was a fertility symbol associated with agricultural rites connected to the god Mars. A Romano-British bronze found in Wiltshire shows Epona, the goddess of horses who had connections with agricultural fertility, in similar style, with a horse and holding a branch probably of hawthorn. She also holds a dish and wheat, other symbols of agricultural fertility. It seems likely that an ancient ceremony was recalled by the monks, or by a monk, from Coventry who turned it into a miraculous tale of self-sacrifice, and thus the Godiva legend was born.

THE HOUSE THAT LEOFRIC BUILT?

It had always been believed that Coventry’s first cathedral and monastery was founded by Earl Leofric and Lady Godiva but it has recently been suggested that they did not found the monastery but only endowed it. The arm of St Augustine was presented to Coventry church in 1022 and those who have chosen not to believe in the existence of St Osburg’s claim that the only church which could have been extant at this time was St Mary’s Monastery, the later Priory. The foundation date of 1043 has had to be recalculated back to 1022 or earlier. The confirmation charter of Edward the Confessor, the original source for the later date, already known to be a forgery, is now considered totally spurious.

For the foundation and endowment of St Mary’s we rely mainly on charters which are known to be forgeries or, more properly, copies, with additions made later to help the prior with claims upon lands and liberties that were not strictly his. The earliest known charter relating to Leofric’s foundation of the monastery exists as a copy made on 7 February 1267. It reads:

In the Year of the Incarnation of our Lord one thousand and forty-three, I, Earl Leofric, by the counsel and advice of King Edward and Pope Alexander, who sent to me his letter written below, with a seal, and by the testimony of other devout men, laymen as well as churchmen, have caused the Church of Coventry to be dedicated in honour of God and Saint Mary His Mother, of Saint Peter the Apostle, of Saint Osburga the Virgin, and of All Saints.

Therefore I have given these twenty-four towns together with a moiety of the town in which the Church, for the service of God, and for the food and clothing of the Abbot and monks serving God in the same place …