Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

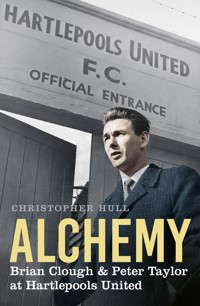

Alchemy reveals the bittersweet reality of Brian Clough and Peter Taylor's first management job together. The lower-league Hartlepools United are penniless, with a meddling chairman, a ramshackle ground and want-away players. Yet the management pair tackle every challenge head-on, forging a winning blueprint that later transforms unfashionable Derby County and Nottingham Forest into League and European Cup champions. Exploiting a wealth of archive newspapers, plus interviews with those present at the creation, Alchemy exposes the humble origins of Clough & Taylor's meteoric rise to the top of the football tree.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHRISTOPHER HULL is a senior lecturer in the Centre for Student Exchange and Language Development at the University of Chester. Despite being born and raised in London, he has been following Hartlepool United since 1978. Alchemy is Hull’s third book. His second delved into the real story behind Graham Greene’s 1958 spy-fiction classic Our Man in Havana and its 1959 film version. William Boyd described Our Man Down in Havana (Pegasus, 2019) as ‘a revelation and a delight’.

Cover Illustrations:

Front: Northern Daily Mail

Cartoon graciously provided by North News & Pictures Ltd

First published 2022

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Christopher Hull, 2022, 2024

Map illustrated by Rick Britton; © Christopher Hull

The right of Christopher Hull to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-80399-146-7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Prologue

1 Hero to Zero

2 ’Boro Days

3 Never Give Up

4 On the Scrapheap

5 The Fear

PART I: HARTLEPOOLS

6 The Hartlepools

7 Little Town Blues

8 V for Victor

PART II: THE 1965/66 SEASON

9 Phone a Friend

10 Buckets & Feathers

11 Howay, howay, howay

12 Polishing a Diamond

13 Parking the Bus

14 Tightrope

15 Steam Stopped Play

PART III: THE SUMMER OF ’66

16 Summer Jobbing

17 England’s World Cup

18 Taylor-Made

PART IV: THE 1966/67 SEASON

19 Mission Statement

20 Driving the Bus

21 Ord from the Board

22 On His Bike

23 Lead into Gold

24 Let there be Light

25 Drive My Car

26 Not Cricket

CONCLUSION

27 Snookered in Scarborough

28 Top of the Tree

29 Turning the Corner

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

1 May 1993

The final whistle is about to blow on Brian Clough’s twenty-seven-year management career. In the Premier League’s inaugural season, a home defeat condemns Nottingham Forest to the First Division. Just days from retirement, Clough suffers his first-ever relegation as player or manager. Sporting his trademark green Umbro sweatshirt, he slurs his words in post-match interviews. Worn down by alcoholism and stress, red blotches speckle his face. Clough begins the banter cheerful but ends it tearful. His verdict on relegation? The team and their manager were ‘not good enough’. He thanks the men behind the microphone for their professionalism over the years, while they salute him for entertaining us. The BBC’s Barry Davies, himself a legend, receives a hug and a kiss.

The end resembled the closing scene in a Shakespearean tragedy. Two lead roles had been central to the football drama, but Clough played out its fifth and final act alone.

As a pair, Brian Clough & Peter Taylor were household names in British football from the late 1960s until the early 1980s. Their characters and talents chimed to produce inimitable chemistry and amass trophies. When they were firing on all cylinders, the effect was magical. In five years at Forest from 1976 they won two League Cups, the First Division Championship, and back-to-back European Cups. In similar fashion, they steered Derby County from the lower reaches of the Second Division to the First Division Championship in 1972. The Clough & Taylor brand was synonymous with transforming underperforming teams at unfashionable clubs and turning them into serial winners.

But when the two elements of the formula were apart, there was no spark of chemistry. For example, Clough never fully committed to Brighton & Hove Albion in the years between managing Derby and Forest in the East Midlands. The pair barely made an impression at the south-coast club. And when Clough went it alone during forty-four infamous days at Leeds United in 1974, the results were disastrous.

Yet when they were together and in top gear, as at Derby and Forest, nobody could hold a candle to them. Brian Clough was the charismatic half of the double act. Due to regular television appearances, his nasal Yorkshire drawl was seared into the national consciousness. When he spoke, the public listened. In his own mind and the minds of many listeners, he spoke truth to authority. But for others, his big-mouth brashness and overconfidence were a turn-off.

Peter Taylor was seven years his senior, but nowhere near as telegenic. Away from the limelight in which his partner basked, he was the more ambitious and strategic-thinking man. He also liked to gamble, literally and metaphorically, trusting his instincts to take a punt. His eye for talented players and bargain buys, as well as horses, was second to none. Together, the Clough & Taylor brand was as complex and balanced as a fine blended whisky, but not to everyone’s taste.

Before they first hit the big time at Derby, the pair served their joint-managerial apprenticeship at the base of the football pyramid. During a nineteen-month baptism of fire at the Cinderella club of North-East football, they tackled all manner of challenges and difficulties. The club had never won promotion and lay next-to-bottom of the Fourth Division. It had applied for re-election to the Football League in five out of the previous six seasons. With few pennies to rub together, its council-owned ground was one of only two in the league without floodlights.

Clough & Taylor’s rocky journey to the top of the football tree therefore began at its very bottom.

1

HERO TO ZERO

December 1962

Beginning on Christmas Eve, a Siberian anticyclone joined freezing air from the North Pole to inflict one of the harshest ever winters on Great Britain. The Big Freeze of 1962–63 held the country in its icy grip until March, with -20°C temperatures and 15ft snowdrifts paralysing everyday life. For weeks on end, no number of braziers, groundsmen’s pitchforks or bales of straw could prevent decimation to the Football League programme.

Boxing Day’s fixture list suffered nineteen postponements and another three abandonments. Matches called off included Middlesbrough v Norwich on Teesside. Sunderland’s home fixture up the North-East coast only survived thanks to Wearside’s proximity to the relatively temperate North Sea. Despite the referee deeming the half-frozen pitch playable, however, a pre-match hailstorm left it more treacherous still.

Wrapped up against the rotten weather, the fans streaming through Roker Park’s turnstiles were full of expectation. Sitting second in the Second Division, Sunderland’s promotion hopes were pinned on the red-and-white-striped no.9 shirt of their plucky goal-a-game striker. Ahead of the match he was seen dancing on the balls of his feet in the stadium’s foyer, describing the goals he’d score. With a record of twenty-four goals in twenty-four games that season, few questioned his cocky self-confidence.1

The game against Bury, the best attended in the country, started brightly for Sunderland. Their first big moment of excitement came in the 16th minute, a dress rehearsal for the calamity to come. Bury goalkeeper Chris Harker up-ended their star centre-forward Brian Clough as he pounced on a cross, only for Charlie Hurley to skew the resulting penalty wide.

Recollecting the second and far more pivotal 27th-minute incident three decades later, Clough explained: ‘I’d got my head down into the penalty area chasing a bad ball into the box … The goalkeeper came out a bit barmy. Anyway, I went over him and I did my knee and I did my big head … and I finished up in the infirmary in Sunderland.’2

Veteran North-East football correspondent Doug Weatherall remembers the Boxing Day game as if it was yesterday:

I can see him now on the icy ground, watching the ball over his shoulder. Brian’s weight was behind him as he was stretching. The advancing goalkeeper had his weight forward and there was a terrible collision.3

He crawled through the slush on all fours, slumped on his backside in the six-yard box, and pounded the pitch with his right palm. Everyone packed into Roker Park knew it was a bad one.

A photo sequence told the story the next day under the headline: ‘The clash that could cost Sunderland promotion.’ ‘Clough, his face twisted in pain, lies helpless on the muddy carpet of Roker Park’; ‘The crowd falls silent as the St John Ambulance Brigade volunteers carry the injured leader from the field.’4 While the 1–0 home defeat to Bury was Sunderland’s first in thirty-two league games, the fans had lost much more than a football game.

The deathly hush that rippled through the Boxing Day crowd suggested their promotion hopes had shattered like falling icicles from the Clock Stand roof.

Among the crowd that fateful afternoon was a sport-mad and music-loving 13-year-old schoolboy living in West Hartlepool. He’d saved up his pocket money to travel up the North-East coast to Seaburn near Roker by train. John McGovern rubbed elbows on the terraces to catch a good view of the action. Like other supporters at the Fulwell End, he was ‘gobsmacked’ by the turning point on 27 minutes that transformed the game’s festive atmosphere into that of a wake. After departing early to catch a less crowded train home, other passengers on the station platform enquired about the score. Sunderland were losing, he told them, but much more ominously, ‘I think Clough’s broken his leg.’5

Fast-forward three years, and the roles of player and onlooker would be reversed. Without knowing it, the 42,407 Boxing Day fans on Wearside had witnessed a key career- and life-defining moment for Brian Clough. He’d play again, but surgery on medial and cruciate knee ligament damage in the 1960s was not what it is today.

When McGovern met Clough face to face in 1965, it was for a practice game at the ramshackle Victoria Ground, home to Hartlepools United Football Club. (The club would lose its extra ‘s’ after the amalgamation of The Hartlepools – Hartlepool and West Hartlepool – in 1967). The league’s youngest manager, Brian Clough, alongside assistant manager Peter Taylor, recognised a gem who’d play under them for many years to come. Brian Clough and John McGovern’s joint football journey therefore began on Boxing Day 1962, with the mud-spattered striker rueing his ruined right knee.

2

’BORO DAYS

In Brian Clough’s eyes, his Mam kept the cleanest front step on their street. The street was Valley Road on Middlesbrough’s Grove Estate. He was closer to his mother than his father, a sugar boiler in a local sweet factory and a Middlesbrough FC season ticket holder. In the football-obsessed North East, Brian and his father stood on Ayresome Park’s terraces to worship Teesside heroes George Hardwick and Wilf Mannion, famed for his inimitable body swerve.

Sally (known as Sal) and Joe Clough instilled discipline in their children and a love of family life. Liver and onions was a teatime favourite, and there was no TV. Just a wireless, a gramophone and a piano. His Mam, who ruled the roost, spent many hours at the mangle, where Brian often helped her with the sheets.

Born in 1935, Brian was the fourth eldest of six boys along with two sisters. Typical of the day, the six brothers slept three-in-a-bed and were never cold. They all shared errands, while their parents scrimped and saved for the two-week family holiday to Blackpool every summer.

Academically, his brothers and sisters outperformed him. Indeed, a lifelong sense of inferiority arose from him failing his eleven-plus, the only sibling to do so. He cried on hearing the news. While they progressed to grammar school, he attended the local non-selective secondary. He left without any O- or A-levels, a fact he often mentioned in later life when boasting about the silverware he won as a football manager. In his mind, medals and trophies trumped paper qualifications.

Young Brian had a burning ambition to get picked for every team but struggled for selection at Marton Grove Secondary Modern. Resentment at being overlooked smouldered within him. It didn’t help that he was a small child who only spurted upwards from the age of 16 to reach 5ft 11in. His first love was cricket and the Yorkshire and England opening batsman Len Hutton. But his brothers’ preference for a different sport turned him into a football fanatic who drove himself to outcompete them. There were always pairs of football boots hanging behind their coalhouse door, and constant debate about who was the best player. For a time, four Clough brothers – Desmond, Billy, Joe and Brian – played for Saturday/Sunday afternoon village team Great Broughton in the Cleveland League. This left their mother with a large pile of muddy kit to wash every weekend. His other hobbies included collecting birds’ eggs, hunting out the best conkers, and climbing trees to pick apples and pears from the posher areas of Middlesbrough.1

Brian stood out with schoolteachers for his strong opinions on any given topic. Yet despite his cockiness and lack of academic prowess, the school made him head boy, an honour that brought him immense pride. The pleasing taste of authority, wearing a head boy’s cap and instructing his fellow pupils, stayed with him.

He left school at 15 to start an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner at the massive ICI plant in Billingham, racing there on a bike with dropped handlebars and narrow tyres. But his lack of dexterity meant he was unsuited to the work, and an underground tour of an anhydrite mine terrified him. ICI made him a junior clerk, but he was little more than a note-carrying messenger boy who progressed to filling out overtime sheets.2

A schoolteacher’s recommendation led Brian to start playing for Middlesbrough FC’s junior side. Yet no sooner had he progressed from amateur to professional at 17½ years old then he was called up for two years of national service in the Royal Air Force. Posted to RAF Watchet in Somerset, he could barely have been any further away from the North East, although test match cricket on the wireless provided a pleasant distraction. He played football for his station side on Wednesdays and Saturdays but bristled at never being picked for the RAF national team.3

On returning to Middlesbrough, it took far too long in Clough’s mind for him to become a first-team regular. He made his first-team debut against Barnsley on 17 September 1955 and scored four goals in nine games that season. What he termed his ‘Golden Year’ of 1956/57 made him a regular first-teamer and built his reputation as a prolific sharpshooter. He also gained notoriety as a bighead and a loudmouth. He just couldn’t refrain from calling out his fellow players’ shortcomings, particularly their frailties in defence. In Brian’s opinion, and he said so, there was no point in him banging in a hatful of goals up front if they were leaking them by the sack load at the back. Until they resolved the problem, he asserted, ’Boro would be perennial underachievers in the Second Division.

In a situation that would play out again at Sunderland, Clough made few friends in the Middlesbrough dressing room. After initial difficulties establishing himself in the first team, his goalscoring prowess cemented his position in ’Boro’s forward line. The one real friendship he did develop was with a goalkeeper seven years his senior who arrived on Teesside in 1955 after ten years at Coventry City, nine of them under the influential manager Harry Storer.

Born and brought up in Nottingham, Peter Taylor arrived at ’Boro with his young family and soon began to mentor Brian Clough. He couldn’t understand why his new younger acquaintance was not a regular in the first team given his goalscoring ability. ‘This fair-haired boy of 20 was the greatest player I had ever seen. I knew then that he must find success,’ Taylor said later. With a keen eye for football talent, developed under Storer, Taylor persuaded ’Boro manager Bob Dennison to give his cocky colleague more opportunities in the first team. Like most of his football-related judgements, Taylor was spot on.

Bachelor Clough and family man Taylor hung out together. The junior partner made regular visits to Taylor’s home, where they’d spend endless hours discussing football. They travelled top-deck on buses to take in countless matches around the North East. The pair talked tactics and honed a joint philosophy about how the game should be played, and how managers should manage.

Under Storer at Coventry, Taylor had studiously observed how his manager spotted and acquired talented players, often at bargain prices. And furthermore, he learned from him how to discern and exploit their best attributes. Storer was not a man to suffer fools in his dressing room or in the boardroom, and liked the game played hard.4 Taylor had become a disciple of Storer at Coventry, as Clough would become a disciple of Taylor at Middlesbrough. His new friend became his champion in the ’Boro dressing room. Beyond his footballing nous, Taylor also made Clough laugh with his observational dry wit. Furthermore, he told him to his face when he was wrong.

In 1957, Clough began to date a local girl he met at the Rea cafeteria, a regular player hangout for a milkshake and a chat. Brian considered himself the luckiest man in the world to have met her, and after two years of courting he married Barbara in 1959. Like Peter Taylor, she was able to keep him on an even keel, at least most of the time.

On the one hand, Clough had good reason to be cocky. His goalscoring record was phenomenal and the statistics spoke for themselves. In four consecutive seasons at Middlesbrough he scored more than forty goals. In the 1957/58 and 1958/59 seasons he was literally a goal-a-game striker, with stats of 42/42 and 43/43 games to goals respectively. Two of his goalscoring records still stand today, perhaps never to be surpassed. In total, he scored 251 league goals from 274 starts. Only three weeks before his life-defining injury, Clough had completed the fastest 250 goals in league football. Like his record in reaching 200 goals, it still stands. Among this goal frenzy, he scored eighteen hat-tricks at Middlesbrough and Sunderland. In addition to these, he scored four goals on five occasions at Middlesbrough, and once bagged five goals in a 9–0 hammering of Brighton at Ayresome Park in August 1958.

Clough was renowned as a fox in the 6-yard box, pouncing on any sniff of goal. He’d often pick up the ball in midfield, distribute it accurately to either wing, to dash forward into the open space for a quick return.5 The near post was his main bread and dripping.

There is one large caveat to these records, however. All Clough’s goals, bar one, were scored in the Second Division. The lingering question is why no First Division club bought him if he was that good, and why he won just two full England caps. He would have told you that it was due to the rank bad judgement of First Division managers and England team selectors. According to Clough, and some agreed, England played him in the wrong position or in the wrong formation. Others reckoned his lack of progression up the league and at international level had a lot to do with his oversized head and salty tongue.

As well as possessing an uncanny ability to score goals, he also excelled in rubbing up people the wrong way. In a notorious episode at Middlesbrough, for example, most of his teammates signed a round-robin requesting that the club withdraw the captaincy from him. Instead of shooting his mouth off, Clough shot a hat-trick in their next game to help sink Bristol Rovers 5-1. Manager Bob Dennison quipped that his players should repeat the round-robin if it was going to have that effect.

Doug Weatherall had attended a game at Carlisle and stayed the night in the town. He was supposed to cover a game at Workington the next day when his office called and instructed him to get over to Teesside and cover the story.

Doug sped to Clough’s house in Middlesbrough, but on his arrival spotted a car belonging to Len Shackleton, a former Newcastle and Sunderland footballer and now working for the Daily Express. Derrick Hodson was there too, working for the same newspaper. They had unfortunately beaten Doug to scoop the headline story that Clough was requesting a transfer. Nevertheless, when Doug asked Clough out of his rivals’ earshot how the episode made him feel, he lamented, ‘It’s broken my heart.’6

Clough carried the hurt for another two years before ending his playing days at ’Boro. After a sixteen-day summer cruise in the Mediterranean with his wife Barbara, their ship docked at Southampton early one morning, where the suntanned Sunderland manager Alan Brown awaited them. With the two North-East clubs having already agreed a deal, he’d interrupted a holiday in Cornwall to try and seal it. It took the two men just six minutes to shake hands on Clough’s salary. A month after Peter Taylor’s departure for Port Vale, a transfer fee of £45,000* took the prolific centre-forward up the A19 from Teesside to Wearside in July 1961.

________

* Readers interested in modern-day equivalent prices should use www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

3

NEVER GIVE UP

The Cloughs slid into personal hell on Boxing Day 1962. Following his injury, Brian found himself in Williamson Ward 2 of Sunderland Accident Hospital. Even his wife Barbara was unable to visit him, as she was confined to bed at home with flu.1

The couple’s friend Doug Weatherall saw him the day after his injury and immediately enquired, ‘What’s the score Brian?’

‘They tell me that everything in my knee’s gone.’

When Doug described the injury to Newcastle United’s physio, his verdict was ‘he’s finished’. According to Doug, however, ‘Brian never admitted that his career was over’.2

Barbara did eventually visit her husband four to five days later, only to inform him she’d suffered a miscarriage. Brian was unaware she was even pregnant. With stitches from cracking his head on the icy pitch, to having his entire leg in plaster from ankle to groin, it had turned into a joyless Christmas. When he was ready to leave hospital, Alan Brown gave him a lift home and literally carried the player on his back from the car door to the threshold of his club bungalow on St Nicholas Avenue. Clough admitted he was not the easiest husband to live with during this period, resting his shattered knee on the cushions of their red G Plan settee.3

In early 1963, the Big Freeze led to so many P-P (postponed) entries in weekend fixture lists that the three main Football Pools companies – Littlewoods, Vernons and Zetters – set up a Pools Panel for the first time. The six-man team of experts met behind closed doors to decide who would have won the matches had they been played. The BBC announced their guesstimates on live television.

Elsewhere, the Big Freeze paralysed roads, railways and airports. Snowploughs, shovels and rock salt attempted to get the country’s lorries, trains and planes moving again. But that was cold comfort for the nation’s farmers, who struggled to get their produce out of the frozen ground. A vegetable shortage resulted, and the price of cabbages, carrots and potatoes shot up.

Upon seeing Clough’s injury on Boxing Day 1962, Alan Brown had immediately deemed the situation hopeless. Yet neither manager nor club physio John Watters could tell Clough because it would have ‘shattered him’. They judged he needed at least a sliver of hope to cling onto over the difficult months that followed.4

Brown thus paid more attention to the psychological blow suffered by his star centre-forward. In the next day’s newspaper, he declared ‘this COULD be a long one’. While stressing it was ‘a big blow’ to the club and its fans, he underlined that ‘the player is suffering more than we are’.5

He did his utmost to soften the blow by driving Clough hard to recover from crippling injury, despite the futility. Brown had been through the same sad process before. As a trainer at Sheffield Wednesday, he’d had to tell Derek Dooley his career was finished after the centre-forward broke a leg playing at Preston. More tragically still, Dooley had to have his leg amputated.6

On the weekly Football Echo’s front page ten days after his injury, Clough thanked the legions of Clock Standers and Roker Enders, etc., who had sent messages of encouragement to him. His ‘secretary’ – his wife Barbara – had answered them all.7 But he sounded much less chirpy two weeks later: ‘The thought of being out for the season has brought hours of depression. It would be wrong for me to say otherwise. I was enjoying my football more than at any time in my career and beginning to feel that Sunderland could take on anybody.’8

By the time they removed his leg plaster in late March, Clough was still top scorer in the league, despite not having played for three months. He was relieved to see the back of the cast, and the Echo’s front page pictured him completing a giant jigsaw alongside Barbara at home.9 Two months later his crutches had given way to sticks, and his depression to determination. But hard work alone would not compensate for his crippling knee injury.

Renowned as an arch disciplinarian with a soft underbelly, Alan Brown drove Clough hard during his convalescence. In late June, Clough was leaving his car at home to walk to Roker Park to regain fitness on its terracing and perimeter track.10 He sprinted up and down the fifty-seven steps of Roker Park’s terracing, often with Brown in tow for moral support. He used a diminishing pile of forty football boot studs to keep count, and even chased pigeons to gain fitness. Alone, he sprinted up and down Seaburn’s Cat and Dog steps on repeat, never doubting he’d make a full recovery.11

His period of convalescence reinforced Clough’s respect for the North-umbrian’s ironclad rule. It was indeed the lean and upright Brown who taught Clough most about discipline, applied to the individual and to his teams. The player admitted to being frightened of a manager whose ‘bollockings’ he defined as being worth ten from anybody else. Instead of tearing a strip off players, he tore off their entire shirts.12 According to Doug Weatherall, Corbridge-born Brown was ‘the most formidable manager’ he ever met. ‘Anybody who can deal with Alan Brown,’ he told me, ‘can deal with any other manager.’13

Clough revered Brown like a subordinate does his commanding officer. Indeed, Brown ran his teams like a sergeant major does a parade ground. He was the dictator that Clough aspired to be. In time, others would consider Clough’s supreme confidence – as they did Brown’s – as arrogance spilling over into conceit.

Brown had dropped two severe ‘bollockings’ on Clough’s head on his first day of training at Sunderland. Firstly, for speaking to a friend at the training ground perimeter fence in the morning; and secondly, for enquiring about the England cricket team’s test match score at Roker Park in the afternoon. After a good start on the pitch, his new manager then dropped him from the first team for being a ‘a little stale’ while praising the way he reacted to it. In Clough’s opinion, he was ‘the man with the firm hand but warm heart’. According to him, for ‘all his outward toughness […] there’s no manager more human, more discerning than Alan Brown’.14

After a playing career as centre-half for Huddersfield, Burnley and Notts County, Brown had entered the police force before returning to football as a coach and then manager. He had dragged Sunderland’s reputation out of the mire following a corruption scandal in the late 1950s in which the club was heavily implicated and made a scapegoat. They had for years bent the rules by making illegal indirect payments to their players when a maximum wage existed for professional footballers.15 Thenceforward, Sunderland’s board of directors were renowned for caution and penny-pinching.

Meanwhile, Brown was known as a harsh disciplinarian with a strong moralistic bent. He had a fixation with players’ personal conduct. For example, he frowned on players smoking and drinking, and abhorred them ‘boozing’ in public. He had zero interest in the permissive society of the 1960s. Above all, he inculcated self-discipline in his players. Rarely did they step out of line, and when they did, they felt his wrath. Furthermore, he involved himself in his players’ problems, however small. Called the ‘The Iron Man’ of football by the British tabloids, and ‘the Bomber’ by his players, he led by example through full application to the job in hand and attention to detail.16

Come December 1963, it appeared to be all over for Clough’s footballing career. Sunderland’s Football Echo correspondent Argus (a nom de plume) affirmed there had never been more than ‘an outside chance’ that their free-scoring centre-forward would recover from the worst type of knee injury that could befall a player. As others before him had found, there was ‘no comeback’ from such ligament damage. His had been a ‘brave battle’, but it was never more than ‘a forlorn hope’.17

Medical experts advised Sunderland that if Clough attempted to play football again, another tackle could turn him into a cripple. But as the Echo affirmed, the experts’ most difficult task was ‘convincing Brian’. Asked if he should defy doctors’ orders, Alan Brown counselled that ‘they know best’.18

On the one hand, Clough seemed resigned, saying, ‘I’ve tried for a year to beat the injury. Now I’m told it’s hopeless.’ Apart from his delicate knee, he was perfectly fit and training with the rest of the team, and kicking balls ‘just as hard, just as accurately as ever’. He had insured himself for £1,500 against a career-ending injury and stood to collect £500 from the players’ union insurance fund. But that was small compensation for a player many rated as the best centre-forward in Britain. Clough lamented, ‘Football to me wasn’t only my career. It was my whole life.’19 It wouldn’t solve all his troubles, but Sunderland had promised him a testimonial game.

Meanwhile, Brown appeared to offer a valedictory on his playing career: ‘Clough’s great goal-scoring record speaks for itself. His greatest asset? His confidence. His belief that no matter how things were going against him he would get a goal. This is a rare quality. He also has a unique style.’20

Walter Turnbull joined in too, writing that his early retirement would be ‘a great loss to the game’, while hoping he’d find another outlet in the sport for his ‘unbounded enthusiasm’.21 At the same time, legendary Newcastle striker ‘Wor Jackie’ Milburn lamented the ‘cruel blow’ that had deprived modern-day football of one of its ‘greatest’ centre-forwards. He deemed him ‘a soccer addict who lived for football’.22 Alan Brown’s apparent final verdict was that: ‘This truly is a great tragedy for all of us.’23

On reading news of his early retirement from the game, the Richmond (Yorkshire) division of the Labour Party asked Clough if they could put his name forward for nomination as candidate. It wasn’t the most enticing offer because Richmond was one of the safest Tory seats in the country. And it wasn’t the first time he’d been asked to go into politics. Even when playing at Middlesbrough, he had been approached about being a town councillor. The Sunday Mirror described Clough as ‘an able speaker’. And whether it was judo, snakes and ladders, or soccer, he always played with ‘a tremendous killer instinct’ but ‘with scrupulous fairness’.

He didn’t enter the cut-and-thrust of politics, despite the temptation to do so. What he was certain about was that the suspense and agony of sitting on the sidelines was destroying him. He told the newspaper: ‘I wait in the treatment rooms as the lads trot along the corridor to take the field at five minutes to three. The sound of those studs shuffling along the concrete pulls my heart out.’24

With time on his hands and strong opinions to voice, The People newspaper knew a good thing when they saw it and published a series of three weekly articles by Clough. The now apparently retired loudmouth of football did not hold back. In fact, he gave his critics both barrels.

The headline of the first two-page spread described him as ‘soccer’s odd man out [and] the Goal King with a grudge’. For starters, ‘Mr Goals’ demanded to know why he’d been cold-shouldered by the England selectors when he was soccer’s ‘most consistent scorer’ and ‘banging in the goals left, right and centre’. He neglected to mention at this point that all these goals had been scored in the Second Division. Apparently, there had been ‘half a million fans screaming “Clough must play for England”’.

He couldn’t get over how ‘bitter’ he felt, although he did recognise he’d been tagged ‘a difficult character, a big head … [and] a bad mixer’. Clough recounted an England training camp at Roehampton when a party of England players had organised a shopping trip to Central London. Clough and fellow north-easterner Bobby Charlton had decided to watch birds nesting in a local wood instead.25

The second article began by proclaiming, ‘I hope the England selectors read this.’ You can be sure they did, and that they didn’t forget the experience quickly. Again, he couldn’t fathom why he hadn’t been picked more for England.

When it came to the round-robin episode at Middlesbrough, he cited some (from the majority) who’d signed it:

‘Brian howls at me on the field.’

‘He doesn’t mix with us in card schools at away matches.’

‘He doesn’t act like a captain.’

What they had failed to understand, apparently, was that everything he said was ‘in the heat of the moment and forgotten immediately’.26 It might have been instantly forgotten by Clough, but was forever remembered by those at the sharp end of his tongue.

In the third article, meanwhile, he asserted that people simply misunderstood him. Rather than wanting to run the show, as he had at Middlesbrough, he preferred ‘a tough guy for a boss’. Be it Brown at Sunderland, Stan Cullis at Wolves, or Harry Storer at Derby, he respected sternness. In fact, seeking Storer’s advice, the Derby manager had advised him to join Brown at Sunderland.27

While the three weekly articles did nothing to endear him to his fellow players or the England establishment, who he had already antagonised in the extreme, they did demonstrate an aptitude for courting controversy and getting his message out. Newspapers weren’t shy to give him column inches, and the public was keen to read what he said.

Despite missing Clough’s goalscoring prowess, Sunderland still got within a whisker of promotion in the 1962/63 season. They missed out on goal average, with Stoke City crowned Second Division champions on 53 points, and Sunderland placed third behind Chelsea on 52 points apiece. While both rivals had performed similarly at home, Sunderland’s defence had shipped more goals and points playing away from Roker Park. Up to the First Division steamed Stoke and Chelsea, while Sunderland stayed put. Would Clough’s missing goals have made the difference? The only thing we can be sure about is that Clough himself would have thought so.

Sunderland prospered during the 1963/64 season, despite Clough’s continued absence. Yet after finally achieving promotion in April 1964, the resignation in July of Alan Brown after seven years at the club to take over at Sheffield Wednesday came as a hammer blow to Sunderland supporters.

Eight months after medical experts had advised Clough to pack in the game, fresh opinion on his fragile knee left the decision with Clough. His last word deemed that he re-signed for Sunderland and began pre-season training alongside the rest of the team in the summer of 1964. Hovering over the question of his return to action was insurance compensation to the tune of the £40,000 that was due to the club should he take early retirement.28 On reporting back for pre-season training, Clough declared himself ‘as fit as a fiddle and rarin’ to go’. He’d been training alone at Roker Park thus far, but now led colleagues on 2-mile runs and strenuous workouts ‘without raising a sweat’.29 Cloughie refused to call it a day.

With his hopes raised of a return from the ashes to wearing the Sunderland no.9 shirt again, Clough turned out on the cricket oval for a Footballers & Sportswriters XI v Wearmouth XI match. He opened the batting with a knock of 32 runs before being stumped. With ball in hand, he took one wicket for 32 runs.30 Meanwhile, the local press talked up the possibility of him returning on the football pitch. ‘Can Clough confound medical opinion and conquer an injury which has put many a top man out of the game for good?’ one newspaper asked.31

Another local headline declared: ‘45 minutes from truth: Brian Clough’s biggest gamble.’ Only Clough could know the tremendous risk he was taking, the report suggested.32 When he appeared for a second-half appearance in a pre-season friendly against Huddersfield, ‘sentiment ran wild’ among the near-25,000 Roker Park crowd. Wild cheers erupted every time he touched the ball in his first comeback in the second half of a friendly against Huddersfield. There was no doubt he could still play football, the Sunderland Echo affirmed, but could he perform at the top level?33 The player himself moaned he had scarcely got a kick of the ball, but left the next step to Sunderland’s directors.34 And it was the Sunderland directors rather than the club’s manager who would decide Clough’s fate in a board meeting on 19 August 1964. It was also the directors who decided team selection, and that was because Sunderland were still without a manager at the start of the 1964/65 season. The club were back where they wanted to be in the First Division but had yet to find a replacement for Alan Brown.

Clough’s first competitive game was against Grimsby Reserves at Blundell Park, hitting the goal trail again on 78 minutes with a low free kick from 20 yards. During a fifteen-minute spell, the Sunderland Echo’s reserve-team correspondent Vedra judged that he looked like the player who was ‘terrorizing Second Division defences’ twenty months previously.35 His first competitive appearance at Roker Park, on 29 August 1964, swelled the attendance to five times its normal size. Clough ‘thrilled’ fans with a ‘vintage’ hat-trick, ‘toying with’ and tearing through the opposing defence, although it did belong to Fourth Division Halifax Town’s Reserves.36 Despite the lowly opposition, Clough declared himself ‘ready for First Division football’.37 Yet he was running a dire risk every time he played football. Nothing more than nylon stitches attached his severed knee ligament to the bone.38

Nine months after his declaration that he would never play again, and having ‘never stopped hoping and fighting’ to build up strength in his injured knee, Clough’s fourth and largest step was his return to first-team action at home to West Bromwich Albion on 2 September 1964.39 Yet there was a serious danger of over-hyping his return. The Daily Mirror declared that the Sunderland goal ace ‘written off’ by doctors after a serious knee injury was now making a miraculous comeback.40 In what was his first ever appearance in the First Division, a 52,000 crowd saw him make an encouraging comeback in a 2–2 draw, adopting his favourite near-post position, showing much of his ‘former dash and fire’, and cracking a shot against the base of the post.41

Three days later he spearheaded Sunderland’s attack at home to a Leeds United side featuring Norman Hunter, Jackie Charlton and Billy Bremner. After a corner kick, Clough celebrated scoring with a header into an empty net from under the bar in the 51st minute. In a 3–3 draw, it was his first ever goal in the top division and his last in professional football.42

In his next and final game, Sunderland came from behind again to salvage a draw at home to Aston Villa. Yet the Echo correspondent judged that neither Johnny Crossan nor Brian Clough ‘made any real impression’ in attack. It was ‘uphill all the way’ for Clough. While carrying the sympathy of the crowd, he was ‘lacking his old pace and power’.43 In Argus’s opinion, Clough hadn’t convinced and still had a long way to go. Sunderland’s directors had rushed him into the side on the strength of a good performance against Halifax Town Reserves.44 Argus reaffirmed his position the next day too, describing how they’d recalled Clough too soon, when ‘the pace and power which one made him the most feared leader in the game is no longer at his command’.45 He’d thus made three first-team appearances in the First Division, and Sunderland had drawn all three.

Sunderland’s directors dropped Clough for their next game at Arsenal on 12 September 1964, and he stayed out of the side. The People forecast two weeks later that he’d played his last game for Sunderland, with the club about to agree liability terms with their insurers. It turned out they’d jumped the gun by several weeks.46

4

ON THE SCRAPHEAP

Dropped from the Sunderland team, the man whose ambition had been to score more goals in the First Division than Everton legend Dixie Dean had found a new vocation by October 1964. Megaphone in hand, he was pictured canvassing for the Labour Party in Sunderland South.1

In November, the insurance company that had four months earlier decided it would not be unreasonable for him to play again, asked their London specialist to re-examine Clough’s knee.2 Now that it had been tested in competitive football, he travelled down to the capital with club physiotherapist John Watters.3 The verdict was negative, so adding a definitive full stop to a brilliant but truncated football career.

Sunderland needed the £40,000 insurance cash to buy a new centre-forward. Despite all the huff and puff and dreams of returning to spearhead Sunderland’s forward line, Clough had played his last game in professional football.

The bombshell decision left Clough embittered and sent him into a tailspin of resentment and self-pity. Fortunately, a stroke of good luck and judgement soon dragged him out of despair. It resulted from Sunderland’s directors finally appointing a new manager. Former Middlesbrough defender and captain George Hardwick gave up his job with an oil company to return to full-time football in the North East.4

Like most football managers, he hit the ground running and shuffled his coaching and playing staff. Interviewed decades later, Hardwick affirmed that Clough was causing ‘all hell in Roker Park’ when he arrived. He was ‘bitter and twisted’ about not playing and ‘hated everybody in sight’. The crocked star forward would stand in the tunnel as ex-colleagues jogged onto the pitch, barking in their ears, ‘Who the bloody hell are you? You can’t play. You should never be in this team.’ And according to Hardwick, the sulky ex-player told the directors equally ‘how useless they are’. The new manager soon hauled Clough into his office and warned him, ‘No more trouble from you.’ The newly retired player would have to work for his salary, considering he possessed more than enough knowledge of football to run a bunch of kids. The new manager put him with the third-string ‘A’ team. It was the lucky break he needed. A gleeful Clough placed his hand on Hardwick’s shoulder and exclaimed, ‘Hey boss. You’ll do for me.’5

In such a way, the gentlemanly Hardwick did his former fan at Ayresome Park the best turn possible. Instead of allowing him to mope around the corridors of Roker Park, he gave him a new lease of life, something to keep his mind and mouth occupied in a constructive rather than destructive way. Clough would now train the apprentice professionals and part-timers of Sunderland’s Northern Intermediate League youth team. His first game with new duties was an FA Youth Cup second-round game on Monday, 7 December 1964.6 At home to Darlington, 17-year-old ‘Little Bobby’ Kerr starred in an 8–1 demolition of their regional rivals.

The opportunity was the perfect outlet for Clough’s pent-up energy and theories about football. He discovered an innate talent to teach, and a renewed fondness for being in charge. Out went repetitive physical exercise in training, and in came more ball work. Instead of running lap after lap, five- and six-a-side games became the order of the day at their Cleadon training ground. Preparation for matches was key. His own sweat-drenched involvement meant that he and the players sparked on the same wavelength, and ensured they reached their peak on match days, not in training two days earlier. The young players’ positive response to Clough’s coaching confirmed what he knew already – that players under his charge listened to what he said, and he excelled in such a role.7

Sunderland youth player John O’Hare, later to play again under Clough at championship-winning Derby County and Nottingham Forest, remembers how his arrival was ‘a breath of fresh air’ that transformed their training. Before Clough it had all been about ‘running half-laps’. But their energetic new coach concentrated on ‘sharpness, reaction, quick thinking’. John says the youth team players ‘had a lot of time for him’.8

The results of his efforts were impressive. In a remarkable season, Clough and Bill Scott guided Sunderland’s youngsters to the semi-final of the FA Youth Cup, developing and nurturing stars of the future such as Bobby Kerr, John O’Hare, Colin Suggett and Colin Todd. Later in his management career, of course, Todd would play under Clough at Derby.

On the way to the semi-final, Sunderland Youth handed out a rare thrashing to Newcastle Youth in the third round and stormed through to the quarter-finals with a fine 3–1 triumph over Leeds United.9 Sunderland’s team was the youngest they had ever fielded in the competition. Everton Youth, the recognised best side and eventual winners of the FA Youth Cup, defeated the especially youthful Sunderland over two legs in the semi-final.10

On Hardwick’s advice, Clough trained for an FA coaching badge at Durham, but disagreed with the Football Association man running the course. Clough took pleasure in telling and showing long-ball theorist Charles Hughes that he was wrong. For example, Hughes insisted the forehead be used when heading the ball into the net. Clough countered that any part of the head or indeed body could be used to score a goal, so long as you stuck it in legally. According to Clough, the others on the course listened to him and not to Hughes.11 But then he would say that, wouldn’t he. Suffice to say this early brush between Clough and the FA did not go well. It was indicative of what became a near whole management career of conflict with the Football Association. And a lifetime of rubbing people up the wrong way.

Clough was a Marmite character, both loved and loathed by different people. Or by individuals in equal measure but on alternate days. While he thrived in his youth team role, his inability to button his lip continued to antagonise his former first-team playing colleagues and the suits in the boardroom.

His good fortune under Hardwick turned to bad luck when Sunderland sacked the manager at the end of the 1964/65 season, despite them finishing fifteenth in the First Division, seven points safe from relegation. Clough approached his successor Ian McColl to confirm he’d be continuing his work with the youngsters after the Scotsman took over in May 1965. The new manager used the excuse that Sunderland’s directors weren’t keen for him to carry on. Clough believed, instead, that McColl wanted his own men around him.12 But Hardwick bore out McColl’s version of events when he said, ‘The directors would not accept him. They just would not accept him.’13 Clough soon followed Hardwick out of Roker Park. And the club’s insurers finally paid out £40,000 to Sunderland in insurance liability on their retired striker. In the football edition of snakes and ladders, Clough was back at square one.

The twin physical and psychological blows hit him like a steam train. Indeed, he only accepted his career was over when medical opinion and Sunderland football club made the decision for him two years after his injury, in November 1964.

On Michael Parkinson’s weekly Saturday evening TV chat show in 1973, Clough confessed that Sunderland ‘was life to me. They were life to me.’ When informed there was no longer room for him at the club he loved, he admitted to Parky, ‘It kind of shattered me for a period of time. It broke me up.’14

The whole basis of his earning power, his fame, his outward and self-respect, and most importantly his ego, had evaporated. His bad footballing break left him broken-hearted. Without wanting or being able to admit it, he’d been scratching on football’s scrapheap for two years. At 30 years old, not only was his footballing career over, but he’d been sacked from his first coaching role in the game. He’d proved his ability both on and off the field, but his mouth was his undoing. Football was all Clough knew and excelled at. Indeed, football was all he was skilled in.