Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

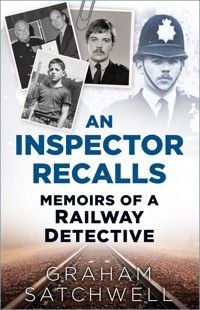

'The best of the genre' - Duncan Campbell, The Guardian Born in inner-city Birmingham, from an 'impeccable working class pedigree', Graham Satchwell was diagnosed with a serious illness at age 7 – a condition which should have barred his entry to the police force. Forty-two years later, he was Britain's senior-most railway detective. In a career that encompassed every CID rank and involved some of the country's toughest gangsters, petty thieves, bomb threats, terrorism, the odd politician and even the Queen, Graham Satchwell has seen it all. Infused with humour and genuine down-to-earth wisdom, An Inspector Recalls is a frank and intimate account of a life spent on the frontier between crime and punishment that recalls the gangsters, politics and often questionable police culture of the 1970s, '80s and '90s.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 526

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR AN INSPECTOR RECALLS

‘I remember Satchwell, he was like “Slipper of the Yard”, but with brains.’

Tom Wisbey, Great Train Robber

‘A lively, funny and interesting jog through numerous interesting policing experiences. Rarely has such a senior detective been so frank! A very good read.’

Michael Fuller, Former Chief Constable of Kent and ChiefInspector of the Crown Prosecution Service

‘A thoroughly amusing, anecdotal record of a man who came to be a legend in British Transport Police.’

David Hatcher, Crimewatch Police Presenter 1984–99

‘A very readable book which is entertaining and amusing, but nonetheless is a contemporary and accurate account of policing throughout that period.’

The Lord Mackenzie of Framwellgate OBE, LL.B (Hons), Former President of the Police Superintendents’ Association of England and Wales

‘An Inspector Recalls conjures up the days when policing was delivered by real men (mostly men in those days), who cared about what they were doing and saw themselves as part of the public at large, not a race apart, which sadly seems to be the case today. By turns amusing, touching and sometimes tragic, Graham Satchwell describes a world we have lost – a world which many would be glad to see return.’

David Gilbertson QPM BSc, Author of The Strange Death ofConstable George Dixon: Why the Police Have Stopped Policing

‘I enjoyed An Inspector Recalls immensely. It is an honest and open account of policing as it was and of the mettle of the man who wrote it.’

Roy ‘Nobby’ Clark, ex-Metropolitan Police and British Transport Police

‘Graham’s readable memoir of thirty years policing is engagingly frank and discloses a recollection of detection, internal politics and police practices that would barely be recognised, let alone acknowledged, in today’s forces.’

Robert Roscoe, Solicitor and Former Chairman of the Criminal Law Committee

Dedicated to George and Eleanor, so that one day they might know me a little better

Cover illustrations: Top: All from the author’s collection; bottom:istockphoto.com/InkkStudios.

First published 2016

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Graham Satchwell, 2016, 2025

The right of Graham Satchwell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75096 834 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 From Nappies to Football Boots

2 Joining the Force

3 Transferred to CID

4 Promoted to Sergeant

5 Temporary Inspector

6 Detective Sergeant

7 Divisional Inspector

8 Detective Inspector

9 Transferred to Force HQ CID

10 The Police Staff College

11 Temporary Chief Inspector

12 A Policeman at University

13 Back to Inspector

14 Chief Inspector

15 Police Staff College – Director of Studies

16 Detective Superintendent

17 Onward and Upward or Over and Out?

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

The hardest part to write is this, the acknowledgements section. If I don’t write one then it looks like I’m being mean and ungrateful to those who have helped and encouraged me. On the other hand if I create a cast of thousands it might seem that I think that I have created something special.

So let me put it this way. There are a few people who you can safely blame, apart from me, if you find the book ill conceived and/or badly written.

Firstly, Don Anthony; he told me back in the 1980s, when he was in his sixties, that I should write such a book. Don had a distinguished life. He was a professional footballer (Watford), Olympic athlete (hammer thrower), visiting university professor (Hong Kong and London), author, and chair of the British Olympic Association Education Committee, though not all at once of course. He was also a genuinely kind, patient and honourable man.

One of my oldest colleagues, David Drury, took time to remind me of stories from our Southampton days together. He also went to the trouble of making suggested corrections to part of the draft text.

Viv Head, another old colleague, read the entire draft and amended some of the many grammatical errors. My recent friend (whom I have only known for twelve years) Peter Benger did likewise.

Michael Appleby, who once defended a man I had charged with manslaughter, read an early draft and encouraged me to complete the book. He also came up with the title, which you might yet conclude, is the best part.

Guy Williamson, former colleague and now barrister at law, somehow found time to read the whole thing twice and then go through it with me line by line to ensure that I haven’t said anything that is actually illegal.

Both the lawyers referred to above gave up their costly time completely freely – and no, in case you are wondering, I don’t ‘have anything’ on either of them.

Thanks also to Andre Gailani at Punch magazine for allowing me to reproduce an old Punch cartoon, and to Tempest Photography for allowing me to reproduce an old police course photograph. Similarly the Southern Daily Echo and the media people at Network Rail and Phillip Caley at Caley Photographic.

Finally, my wife, Lyn. She continues to put up with my never-ending daily efforts to make a success of writing. Lyn thinks my time would be much better spent gardening, or learning to be a better bridge partner. But frankly if I were not pretending to be a writer I’d have to think of something else, painting maybe. I can be so honest with you, dear reader, secure in the knowledge that she will certainly not be amongst your number.

Introduction

Most of my adult life has been spent as a transport policeman, first in the docks and then as a railway policeman – about thirty-one years in all.

You would imagine that anyone who wants to become a hairdresser actually likes the idea of cutting hair. That’s pretty obvious isn’t it? So isn’t it also pretty reasonable to expect that anyone who wants to be a policeman rather likes the idea of investigating crime and arresting wrongdoers? Well, it might be a surprise to you, but many policemen actually shy away from making arrests.

For instance, many years ago I was travelling across London on the Underground with a colleague, we had both just finished duty, and we were both in ‘civvies’. It was evening peak time and the tube train was packed. A few feet away from us a drunk pushed on to the train. My colleague and I were both in our early forties, fit and healthy. The troublemaker was small, thin, and in his late fifties. He looked unfit and was very drunk. So, physically, either of us was more than a match for him.

The drunk was being abusive, and the passengers unfortunate enough to be nearest to him were trying to cower away. The extra pressure of people pushing away from the drunk forced my colleague closer to me than was comfortable. His briefcase was hard against my legs. But here’s the thing: I could feel him shaking with fear. I said to him, ‘Just put that bloody drunk off the train at the next station, otherwise I can see we will all be held up.’ He turned to me, his face no more than eight inches from mine, and I could see the fear in his eyes. He didn’t want to be recognised as a policeman, he didn’t want ‘to get involved’. He was too frightened. Wouldn’t you think it crazy for a man to become a carpenter if he didn’t like handling wood?

Of course there are two ways that a police officer can escape police work. He can resign, or, he can get promoted. Over the years I was in the job it always seemed to me that senior ranks were unfairly treated, I mean they got much more out of the job than they deserved. On the one hand you had constables and sergeants working around the clock screwing their physical health, social arrangements and family life. They frequently took abuse from drunks (not just from CID officers) and had little or no real opportunity to escape for a bit of private time. They got paid less than anyone else.

On the other hand you had blokes (they were all blokes once) in senior positions (inspectors and above), who worked nine to five (or other convenient times according to best suit family/car sharing arrangements). They rarely turned out at the weekend (unless the weather was nice and it was quiet, and they were bored). Otherwise they would only be on duty during unsocial hours if an even more senior officer was going to be there, or there were massive ‘brownie points’ to be scored, and absolutely no chance of anything tricky happening. They worked an absolute minimum of late shifts and never saw the clock strike 1 a.m. while on duty.

Most had very little contact with Joe Public unless giving a talk on the dangers of crime fighting to a Women’s Institute meeting (something they must have learned about by reading crime novels during ‘on-duty’ visits to the public library, or listening carefully to lower ranks – between nine and five). Because they were in a managerial position they had the flexibility of routine to allow them to pinch a bit of time when they wanted. They could put a bet on, sip a cold drink, do a bit of shopping, or pleasure themselves in some other strictly private way. Shouldn’t it have been either senior job (with all the perks) or better money? Why give them both? It seems quite unnecessary and unfair.

As you’ve probably guessed, this book contains a fair bit of fun poking at senior police officers. Of course there were also some very good senior people. But there’s no fun in describing goodness. And of course even those I criticise heavily had their good points.

So, this is a story about my professional experiences. But it isn’t objective. How could it be? It is a highly subjective and creative description of what I remember. That’s all it is. Each experience has been interpreted and reacted to according to my own particular interpretation of the world and my place in it. You will find lots of ‘I said’ and ‘he replied’, and I’ve tried to fairly represent actual conversations. But please remember, some of these conversations took place over forty years ago, and I have no pocketbook to refer to, not any more.

No one can write a book about their experiences and not reveal a little of their character. Even if one were to try, the very act of selecting and telling a story reveals what one sees as important. And as soon as a little ‘colour’ is added, one’s personality is exposed. Everyone has negative aspects to their personality; it is only the nature and extent that varies. Here’s the point, I know that you are not going to like everything I say, but that’s the price I have to pay for making some attempt to tell the truth.

The police on the whole are of course a conservative bunch. Sometimes such conservatism and desire for ‘order’ strays into right-wing behaviour. One unfortunate consequence is that conservatives and right wingers are attracted to the police on the basis of expecting to find a warm welcome. So the whole structure stays on the right. In reality of course, there is nothing inherently ‘right wing’ about strong policing, just look at the record of communist regimes.

This book isn’t an account of all the investigations that I took part in. It certainly doesn’t give any crime statistics or description of the size of the crime problems that the railways have faced. It’s rather a description of some of the things that have stuck in my mind.

‘A society gets the policing it deserves’ goes the cliché. And it’s true of course. When I joined the Service in the 1960s it was much more overtly racist and sexist than it is now. So was our society. The Police Service has gradually become less prejudiced against people of African and Afro-American origins, and against women. That has reflected changes in wider society. But that is not to say that racism and gender bias have been sufficiently removed. After all, you would expect an organisation that remains conservative, and right of centre, to be ‘behind the curve’.

Most police officers are reasonably good at their job, some are awful and some are brilliant. The stories I’ve told here are mainly critical of me, but a fair number of bosses get a bashing too. I have included the real names of participants, except where it would cause undeserved embarrassment to others; deserved embarrassment has been kept wherever legally permissible.

Policing isn’t the most genteel of pursuits. I know this might be a shock to the faint-hearted, but sometimes policemen swear. My approach to writing this book has been that you (intelligent and worldly) readers wouldn’t want reality diluted. You won’t have to turn many pages before you find admissions of real criminal conduct.

Finally, I must say, judging by the stories that old colleagues remind me of now, I seemed to have forgotten most of the fun I was party to. So, before memories fade further, this is some of what I recall.

I hope you enjoy the read, and learn a bit more about the police, and a lot more about the Transport Police.

1

From Nappies to Football Boots

I come from a family of Brummies, not a family of policemen. Some of my relatives have spent a good amount of time in the company of police, mostly following their arrest. We lived in Birmingham until 1952 when I was 3 years old. But by that time Mum had lost a lung because of tuberculosis and so had one of my sisters.

The doctor was clear, ‘You need to move the children away from this environment, move to the fresh air of the countryside.’ So we moved home, the seven of us; by that time we had two lungs less between us than the average number for a family of seven. We moved from ‘Brummingum’ to the sweet air of a council estate in the peaceful village of Southampton.

These days we are all used to the cosmopolitan, but in 1953? I was nearly 4 years old, that’s all, but the memory has stayed with me. The kids living around our new home had clearly discussed the situation, and they presented serious faces as they stood in front of us, the five new kids. Their spokesperson was solemn. He asked, no doubt because of our strange accent and foreign ways, ‘Are you Chinese?’

Dad gave us all nicknames – I was Little Lord Fauntleroy. I hated it, of course, and if I had not shown I hated it, he would probably have stopped using the name. But I always showed my displeasure, and it always amused him. I kept that name until events changed our family life forever. But why did he call me Little Lord Fauntleroy? And why did I hate it? Well, firstly I knew the name was offered as a term of derision, though of course I had no idea about the book of that title.

Compared with my brother, I was indeed Little Lord Fauntleroy. My brother was older, stronger and tougher. He climbed tall trees, he never cried, he took risks. His facial appearance, colour of eyes etcetera, was that of my father’s. Like my father, he was similarly prone to do outlandish things – sometimes causing the local constabulary to come knocking. I, on the other hand, looked much more like my mother. I suppose I was more sensitive – I was too frightened to climb tall trees, I always had a ready smile, I cried when I was teased, I didn’t take risks and, I’m embarrassed to say, I could not stand getting my hands dirty. So ‘Little Lord Fauntleroy’ it was.

I’m the titch next to my big brother. Do we look Chinese? One of my sisters was absent, hospitalised with tuberculosis.

Anyway, Dad got a job in the docks – the heartbeat of the town. Mum and Dad had impeccable working-class pedigrees. Men were supposed to behave in a certain way. Courage, determination, looking after your wife and family, being the bread-winner, being the equal of any other man; these were the values considered most important.

One morning when I was 7 I woke up with severe leg pains, polio was diagnosed and I was rushed to hospital. It was discovered that in reality I had rheumatic fever. I spent several months in hospital, isolated because of the disease, and was absent from school for a year, after which I attended school part-time. The doctors advised that I had been left with a heart murmur.

I was 8 when my brother died suddenly. He complained of stomach ache and feeling sick. Within twenty-four hours my brother was dead. Appendicitis had developed into peritonitis. Those years must have been all but impossible for Mum and Dad. They both worked every minute, and when they were not working they spent their time visiting sanatoriums, hospitals, and mourning their lost son. That was how it seemed.

After my brother died, my father sat me down: ‘Now that Johnny has gone, if anything happens to me, then you’ll be the man of the house, it’ll be up to you to look after the family.’ I was 8. It seemed he expected me to be a man from that moment. I took it seriously for years, it weighed heavily with me. I’m not sure I ever stopped. From about that time, I ceased to be called Lord Fauntleroy; my new name was Champ.

For all of two years Dad massaged my legs and ankles every day to strengthen them. It worked and I loved to play outside again. When I was about 9, Mum noticed a rather distinct bald patch at the back of my head, she took me to the doctor. ‘Ringworm,’ he said, and smiled at me. ‘We’ll soon get you fixed, and when your hair grows back it’ll be all curly.’ Everyone seemed delighted that I would be curly, I’ve never been sure why.

Anyway, I guess the old doctor wanted to be sure of his diagnosis, so I was sent to see a specialist. The specialist had a pleasant, caring manner. He looked at my scalp for just a few seconds. Then he sat down quite close to me and spoke gently. (I remember that the question was directed at me, not my mother, she was being ignored.) ‘Tell me Graham, what is it that’s worrying you? I can see that you’ve been pulling your hair out, what is it?’ He was right of course. But I could never have simply volunteered the information. ‘I suppose that’s the curly hair gone for a Burton then?’ I retorted. No, I didn’t really; I was only 9. In truth I can’t remember exactly what I said, but I do remember I had plenty on my mind.

It was about this time that Dad was arrested for grievous bodily harm. He was nicked by some of the people I would get to know well, fifteen years later. The ill health of his children had made him late for work on more than one occasion, but Dad was a grafter and never missed a minute of work unless there was good reason. On this particular day, he arrived late and another docker had a go at him for unreliability. Dad picked up a heavy metal tool and crashed it down on his accuser’s head. The man nearly died. Somehow, no prosecution followed.

That was not the only violent incident Dad got involved in, they happened from time to time, never through drink, but always because of a perceived slight or an act of injustice.

Dad often brought home stuff that was of questionable provenance. Sometimes it was a bit of ship’s cutlery, sometimes a little chinaware, sometimes bits of copper pipe, or old brass fittings, or just firewood, but I will never forget the helmet.

I can see it now. He had it wrapped in newspaper and tied on the saddlebag of his bike. He had just come in from work, and not even had time to take his cycle clips off. ‘Look at this, Champ.’ He removed the newspaper and exposed an ancient Roman helmet. I had seen enough of them in picture books and on the films to know what it was. Sure enough it was in poor condition, but it was unmistakable. We discussed it all evening. How exciting that find was. We made up various stories about how it might have been lost about 2,000 years earlier.

No apparent sign of the bald patch!

Dad had made friends with the men who worked the dredgers in Southampton Water. Every day they would dredge to ensure that the waterway retained its proper depth. They would dredge the bottom and take a boat full of silt out of harm’s way. Sometimes they found interesting things. Sometimes those things were sold on, given away, or simply went missing. I have no idea whether Dad was simply given it or not, but I had my suspicions.

Those suspicions were rendered fairly conclusive when I saw the fate that awaited the ancient relic. (I’ve since seen similar pieces displayed as valuable museum artefacts.) Dad used to ‘collect’ copper and brass and sell it to a scrap metal dealer; we used to call it ‘spidge’. We were in the shed together. He picked up the helmet that he had brought home the day before, and without hesitation, delivered several hammer blows and threw it on to the small pile of scrap metal. ‘It’s spidge now,’ he said. And that was that.

By the age of 11 my sole occupation was playing football. I played for the school, then the town, and then for the county schoolboys’ team, and took most of the medals at the school sports days. ‘Rheumatic fever’, ‘heart murmur’, they were never mentioned; I was fit and strong. But my play was never quite up to standard so far as the old man was concerned. The problem was apparently, as he put it, ‘You lack the killer instinct.’

I remember being concerned that it might be a quality that was absent in me, in the way that a chess set might have a piece missing. I became determined to find it within myself. I tried hard and convinced myself that it would be there somewhere, although I still couldn’t find it.

When I was about 13, my sister – she was about 17 at the time – married one Jeff Tuppein. He had several previous convictions for armed robbery and other serious crimes. He was a very handsome, wiry and tough individual in his early thirties. Sometimes he travelled to London ‘on business’, other times he was a stevedore in Southampton Docks. The first time I met him he was wearing a very sharp royal blue suit, red braces, crisp white shirt and blue tie, and a revolver in a gun holster on his chest. He might have been my role model, but life didn’t work out that way.

I played for Southampton Boys football team through my secondary school days, every year until I left school. We had a terrific team and only lost one game during the final season. At the age of 16 I was offered a professional football apprenticeship at Southampton Football Club. At the time I just didn’t realise how rarely the door opens on the world of professional football, but there it was anyway, and I pulled it shut and walked on.

I was 16 years old when I finally located my killer instinct. I had been out for the evening and I got home just after 11 p.m., a few minutes after curfew. As soon as I got through the front door the old man started to poke me in the chest and insult me. Dad was in a violent mood. He shouted and threatened me. All I wanted to do was apologise and make a sandwich. But he wouldn’t have it.

The dressing room at The Dell: I’m third from the right on the back row.

I tried to get away from him and he pulled at my lavender-coloured shirt (it was my best shirt) and ripped it badly. I got upset, but he persisted. I went into the kitchen and took out the bread, the cheese and the bread knife. He stood about four feet away from me, facing me, shouting at me, insulting me, goading me.

The bread knife was in my hand when I snapped. I burst into tears and all my fear of him completely evaporated. I went at him with the bread knife, with all the determination that the years of pent-up fear, frustration and indignity had created.

Here’s the shock – Dad scarpered. He backed off at 100mph. Perhaps he thought, ‘Shit, he’s found his bloody killer instinct.’ Thankfully, his tactical retreat was successful, and I have not had to lead my life with the weight of having murdered my father.

Most people never need to find their killer instinct. It has been centuries, perhaps millennia, since it has been a requirement of individual survival, even amongst working-class Brummies. I left school halfway through the school term without any qualifications and with no plans. My only interests in school had been acting tough, playing sport and girls.

I spent some time working part time at a local fruiterers. I liked it. They were a happy bunch and the work enabled me to get some physical exercise, which I always enjoyed. If a lorry arrived and needed unloading I was the first one there – keen to discreetly lift as much weight as fast as I could. I enjoyed being in good shape. But it wasn’t a permanent full-time job.

Being a Gas Fitter’s Mate

I was 16, and I can see myself now, standing in the cold on an open street, watching as old Arthur (master gas fitter) with his miserable face, emptied a hessian sack of steel and copper elbow joints on to the frozen road – this was my first real job. He’d rake amongst them with his gloved hand and select the size needed. Then he would turn and walk away without a word. I soon learned that, as an apprentice gas fitter, my job was to put them all back in the sacks and lift the sacks back into the boot of the old Ford Popular. The process would be repeated several times a day; Arthur always miserable and speechless.

This wasn’t exactly the most stimulating or exciting work. I stayed there about six weeks. My only independent action during that period was to steal several off-cuts of lead piping to make knuckledusters.

Making Knuckledusters

I made them at home, in the shed, about five of them: a special present for my mates to be tried out the very next Saturday night.

Come Saturday I handed the weapons out and the boys carried them proudly as we prepared to meet our mortal enemies – the lads from Hedge End. Both gangs met (as expected, though not strictly by arrangement) at the teenage dance held at the local secondary school. We had the usual punch-up, but the weapons were never used. I think they were much too heavy. Anyway, we abandoned them, though they were found later and made subject of a police inquiry. Thankfully, they never caught me.

Of course if any of us had used one, then the injury could well have been severe, and the trail would certainly have very quickly led to my door. But that would have led to a different life.

Fine Fare

After the fiasco of being a gas fitter’s apprentice I took a job at Fine Fare. The company represented a new concept in shopping – it was a supermarket, a proper one. Ninety-five per cent of the staff were teenage girls, or so it seemed, and I loved the idea.

I remember on my first day the manager talking sternly to me: ‘Keep away from the female staff, if I catch you in the warehouse with one of them you’ll get your cards straight away.’ Mmmmm, pretty girl plus the warehouse equals a good idea, I thought.

I didn’t last more than a couple of weeks.

Geoff and Glazing

One of my other brother-in-laws, Geoff (not to be confused with Jeff), was making very good money from industrial glazing. The money appealed. I knew before starting that it would be a real challenge – I was terrified of heights. But the money was amazing. I was 16 and earning much more than my dad – £4 a day! The work was extremely heavy and my brother-in-law worked with a determination that I had never seen before. No favours were given, and I was the only member of the team that seemed to fear a fall. The others walked as if they had wings across scaffold planks and rigid steel joists high in the air. We travelled around the south. I was ‘on the lump’; a self-employed labourer who had no employment protection or union membership and was paid cash in hand on a daily basis.

On one occasion we were working in London, four of us, starting out by car at 6 a.m. sharp every morning. Two of us had already been picked up. My brother-in-law, Geoff, was driving his blue Zephyr 6. The fourth member of the group’s house – Tony’s – was the last stop. Geoff pipped the horn but there was no sign of life. Geoff pipped again and a light came on upstairs. Geoff cursed. We waited.

About five minutes later, Tony emerged pulling his coat on and apologising for keeping us waiting. Geoff was waiting by the car. As Tony approached, Geoff punched him hard in the face. He went down. ‘Never keep me waiting again,’ Geoff said as he stood over him. Geoff got into the Zephyr and we drove off. Tony was left on the ground; his lateness had cost him some pain, some loss of face and a day’s pay. And that’s how it was.

And in the Evenings and Weekends

The ‘run-ins’ with the Hedge End boys were a regular source of entertainment.

One summer’s evening, when I was about 17, with the other ‘Harefield boys’, I was on my way to the local youth club. A car pulled up in the street just ahead of us. There were about six of the Hedge End boys inside. No doubt they planned to give one or two of us a good hiding if they could find us in such small numbers. What happened next shocked me a bit and came back to haunt me a little after I joined the Force.

Seventeen years old and ready to take on the world, or at least the Hedge End boys.

One of my gang (I remember clearly who it was, but he died in prison as a young man, and it doesn’t seem appropriate to name him) led a charge. The car windows were open and within a second he had grabbed the car keys. We surrounded the Hedge End boys’ car and almost immediately started to rock it from side to side. It became impossible for any of the occupants to get out.

We rocked it harder and harder and each of us became more carried away. Then a heavily built middle-aged man appeared. He was wearing black trousers and shoes, a blue shirt, black tie and a tweed jacket. He said he was a police officer and told us to stop it. But we were all having much too much fun.

We rocked and rocked. The occupants’ pleas and moans were loud but not as loud as our jeering and laughter. The car tipped so much that we reached the point of balance – and it turned upside down and sat on its roof. None of the occupants were keen to crawl out. We made off laughing and congratulating one another. The off-duty policeman remained on the scene.

The Hedge End boys didn’t have exclusive rights, and we would regularly get into punch-ups at teenage dances in the city centre and elsewhere. But no one ever got seriously hurt, and from time to time we all suffered a few cuts and bruises.

I drifted in and out of heavy-labouring jobs. By the time I was 17 my time was spent more in drinking, partying, dancing, and smoking pot than playing football, or worrying about the future. The word ‘career’ was never used by me or anyone I knew. I was a few days light of 18 and I had been out of school for two years.

Meeting Lyn

My life changed completely when I met Lyn. I was 17 and she was 16. I fell for her so completely that there was absolutely nothing I wouldn’t do for her. We both had a working-class background, we were both popular teenagers and she was the most exciting and attractive girl I had ever met. But our backgrounds were different in one fundamental respect. Her parents were both restrained and extremely law abiding.

In fact her mother, who worked at a local hospital, had been warned against letting her daughter go out with ‘Satch’. Apparently the young nurses had told Lyn’s mum that I had a reputation with the girls and was a bad boy.

It’s a strange fact that nothing is more attractive to a ‘good girl’ than a ‘bad boy’. Yet, at the same time, it was clear to me that this girl would lose interest if she thought me at all thuggish, or dishonest. In truth my instincts had never been to be either. But Little Lord Fauntleroys don’t generally come through a working-class environment unscathed, or happy. You have to appear sufficiently tough, and you have to fit in.

Being a teenage devil-may-care, freewheeling seeker of fun is rather different from being a teenage seeker of marriage, job, car, prospects and home. I walked out on yet another job, I was unemployed and neither parents nor girlfriend were impressed.

I thought for some time, perhaps for the first time ever, what I might do to create some sort of interesting professional future, something Lyn might be proud of. Then it came to me: ‘I want to be a hairdresser.’ I visited the Youth Employment Service and sat down with a middle-aged lady advisor. We chatted for a while and I explained that I was looking for a job I could really ‘get into’. She explained to me that opportunities and training were available to people like me. And, at that moment, I didn’t really consider what she might have meant by such a remark, she just seemed helpful.

Anyway, she handed me a long form with lots of potential occupations listed. I looked through them, and there it was, ‘Hairdresser’. I filled the form out eagerly and she watched with a maternal smile. I handed the form back to her. She carefully checked it over and made one or two additions. Then she sat back and smiled at me with affection, ‘What is the nature of your disability?’ she asked.

‘Disability! What do you mean?’

‘Well, what’s wrong with you? Why do you qualify for a hairdresser training course?’

I explained my mistake, she smiled and I left.

The Fish Market

No fish are landed commercially at Southampton Docks. It’s not a fishing port at all. But it does have a fish market, or rather, it did in the 1960s. Fish were transported by lorry from Hull, Grimsby, Lowestoft and all the other main fishing ports, to the market at Southampton. There, about ten fish wholesalers would receive and store the fish in cold rooms ready for onward sale to wet fish shops, and fish and chip shops across Hampshire and Dorset. I got a job with J. Marr Ltd. I became a wholesale fish salesman, and loved it.

My time at J. Marr was good; I think I was enjoying work for the first time. Les Piggott, the middle-aged manager, was very personable and professional. He led a small team of salesmen, warehousemen and drivers. We sold fish by phone. Part of my training at J. Marr was to visit Hull Docks and see how the business operated at a major fishing port. It was a fascinating place. I met up with two other new members of staff as we had all been lodged at a small guesthouse. They were both older than me. One was an ex-bookmaker; he was in his twenties and lively.

He had this party trick, you could throw any value of bet and odds at him and he would work out the winnings before you had time to think. I’d say ‘£1 10s each way and it comes in at 7/2’, and he’d shoot back, ‘I’d owe you £6 15s plus bet money’. Then we would work it out longhand and he was always right, no matter how difficult the mental arithmetic. I learned later that many experienced bookies share this ability. At the time I thought he was a genius. I liked him and we got on well.

The other new member of staff was a portly middle-aged man. I can’t remember much about him other than the fact that he was a gentle, prudent man. He told us that he was still recovering from a very serious heart operation. He had to eat (on restricted diet) at 6 p.m. every evening and be in bed by 9 p.m. He could not drink alcohol, listen to loud music, or become excited, or agitated. We treated him with kid gloves – until one fateful morning.

The Bookie and I had been told to be on dockside at 4 a.m. to witness the fish auctions. This meant getting up at about 3.15. Bookie said to me, ‘Once my head hits that pillow it takes dynamite to get me up. Any chance you could give me a really good shake at about 3?’

‘No problem,’ I replied, ‘I’ll make sure you’re up.’ I grinned. Mr ‘Heart Attack’ had been told that he could rise at 7 a.m. and join us at the J. Marr offices two hours later.

I set my alarm. It went off just after 3 a.m. I went on to the landing and put the lights on. I opened the bedroom door next to mine, and in the half-light from the landing I could see a figure asleep. I tip-toed over and grabbed the occupant by the shoulders and shaking him furiously shouted in his ear, ‘Come on you lazy bastard.’ There was a sort of pitiful cry, the man in bed half turned and cringed, ‘Oh please, please, it’s my heart, my heart …’ To say I felt slightly awkward doesn’t really capture the picture. I left hurriedly.

The small pay that I was receiving from J. Marr wasn’t really satisfying and didn’t now fit in with my aspirations to be a good husband and provider. I tried my hand at working in a kiln at a brick factory, being a timber porter in the docks, being a carpet fitter, and several other trades, none lasted more than a few weeks or months.

The Police?

My dad encouraged me to join the police. They weren’t well paid, but the pay was regular and about average for the working man. But I couldn’t take the suggestion seriously.

He said he had had a word with the coppers in Southampton Docks and that he had fixed me up with an interview. It was 1968; if you were reasonably physically fit and knew your arse from your elbow, you were in. But I had no educational qualifications at all, and to be frank, I was very lucky not to have had a criminal record for assault, possession of drugs, theft and possession of an offensive weapon. Anyway, I mentioned the idea to the girl I intended to marry, and she liked it.

What the hell, I thought, perhaps I’ll try it. It’s only a job like any other, and I’ve had plenty, and they’re ten-a-penny.

One of the men I had worked with occasionally on building sites was a northerner named Joe Cullen. He had done more than one stretch in prison. He was in his late thirties. A career chancer but, like lots of rogues, he was very likeable. One Monday morning he told us that thanks to the police at Southampton Docks he had a miserable weekend. Apparently, he had been invited to go into the docks after meeting an old mate and crew member in a local pub. ‘Come on board, the booze is duty free and we can drink as long as we like,’ sort of thing. Having had a considerable amount to drink he left the ship halfway through the night and started on foot back towards town. He told us that he had been stopped by the police in the docks, and had been questioned about his business there at that time of night.

Perhaps he hadn’t dealt with the situation very well, but it seems he rather ‘fell out’ with his interrogators. ‘What happened?’ we asked him. ‘I got fed up with his questions and so I told him my name was Cullen and that I was related to the chief constable of Southampton.’

It was true that Cullen was the chief constable’s name, but clearly the dock copper questioning Joe wasn’t taking his assertion at face value. He asked a few questions about his ‘relative’ and of course no answers were forthcoming. They were the sort of questions that anyone could reasonably be expected to know about a relative:

What’s his Christian name? What part of the country is he from? How many kids does he have? Where does he live? I guess our northern friend hadn’t thought that far ahead. But the lie didn’t go down well.

He told us that the docks police took him to an area where police dogs were being kept. There was a large area of burning debris. They handcuffed him and took his shoes and socks off. Then they made him run repeatedly across the burning embers.

We all laughed uncontrollably, which of course he knew we would. We laughed and laughed, and he repeatedly called them ‘right bastards’ as he embellished and repeated.

I remembered that story, and I must admit, it made the prospect of joining just a little more attractive! But who were these dock coppers?

2

Joining the Force

1968

The heyday of Southampton Docks was perhaps the 1950s. Yet still in the late 1960s, it remained a distinct and diverse community. It covered several square miles, and every day saw hundreds, and frequently thousands, of foreign and domestic seamen entering and leaving. Today there might be one or two ship movements per day, but in the 1960s there were normally a dozen or more. Some of the docks have since been built upon, and now, like other old ports and harbours, are home to ‘unique maritime apartments’.

The docks are now largely ‘open’, but in the ’60s the port was sealed by a fence, wall and security gate. Anyone entering or leaving by land had to pass through one of the many dock gates, and each one was policed.

Dock workers, enough to support the economy of Southampton and its 250,000 inhabitants, poured in and out of the docks at every hour of the day and night. To suggest that all of them sometimes carried away stolen cargo, smuggled tobacco, cannabis or P&O silverware would be entirely wrong, but only just.

Dad picked up the application forms and we filled them in as a family, with everyone chirping in about the best thing for me to write. There were the usual questions about medical conditions and there, standing out like two red lights, ‘Have you ever suffered from rheumatic fever?’ And, ‘Have you ever been diagnosed with a heart condition?’

My old man was adamant: ‘If you admit that then you might just as well tear the bloody forms up.’ So I lied. I took the completed forms down to the police station in Southampton Docks sometime in 1968, aged 18. The likelihood of my becoming a copper, given my background, was I thought, remote. But here I was anyway, feeling a bit like a traitor to the working class. I was met by a policewoman, or WPC, or ‘Doris’ as they were called in those days, before we knew it was sexist to refer to someone by their gender. She was about six feet tall, with a lean build and a hard face. She had a long scar down the side of her cheek and the demeanour of someone who was about to conduct a reluctant execution. I remember thinking: if the policewomen around here are as tough looking as this, then what will the blokes look like? Just to be fair, I later got to know her, her name was Kathy Keohane, and, though belied by her appearance, she was a gentle, considerate and temperate woman.

Of course I had to take an entrance examination and, as I had never passed an exam in my life, the result was not a foregone conclusion. Somehow I scraped through. Not that you had to be Einstein to be a dock copper, but the test was a standard police test, and my sole preparation had consisted of trying to get a good night’s sleep. I remember there was a general knowledge test, it included being provided with a bare map of the UK on to which I was required to locate at least twelve rivers and twelve towns. I made a fair start: London, Southampton, Birmingham, Liverpool, Portsmouth, the Thames, the River Test, the Mersey … I started to struggle. Locating rivers on maps had not featured heavily as an aspect of life on a building site, timber yard, brick kiln, or fish market.

I looked around for inspiration. And there it was, a large map of the UK prominently displayed on the sergeant’s office wall (now doubling as an examination room). I knew it was cheating. Looking back now I could convince myself that it wasn’t. I mean, perhaps it was more of an initiative test than a geography test. If that were the case, you could justify any sort of devious behaviour designed to outflank the rules so long as the objective was served. Surely Old Bill wouldn’t be looking for people to do that?

A couple of weeks later I had a job interview with a superintendent. He seemed more interested in employing someone who could usefully add something to the divisional football team than someone who could locate the River Trent. Anyway, I scraped in.

It took me years to realise that my old man might have opened up a way for me to get in. He worked in the docks and often spoke about my apparent football prowess (through the eyes of a father). I do know that he was well known to the local constabulary, both Hampshire Police and Transport Police in the docks. And I know too that he spoke on my behalf to my future colleagues, and he had put the idea of joining up in my head.

One night, some years earlier, he was cycling to work at about midnight (he worked with the tides) and saw two men beating and kicking a man who was lying semi-conscious in the road. Dad called out to them to stop, one had a bicycle chain and was using it to whip his victim, and the other was using his boots. They were, in the style of the day, the 1950s teddy boys.

They threatened Dad and told him to mind his own f****** business or else. Dad took the front lamp of his bike and went over. He smashed the lamp against the head of one of them and tore his ear off, he did further significant damage to the other attacker. Then he called the police. The two teddy boys tried to flee but were in no fit state to get far.

Dad bent down to comfort the now unconscious victim. He undid the victim’s topcoat; a police uniform was being worn beneath. Dad saved his life.

Subsequently Dad gave evidence at Winchester Assizes and the two thugs were convicted of attempted murder of a police officer. The police in Southampton treated him like a hero for years afterwards. He was a hero, albeit, a flawed one.

Dad was convinced that an unfair amount of bad luck had plagued his life and was being transmitted by some inanimate object. And when he made up his mind that a certain object was to blame, no mercy was given. Amongst many fatal attacks on inanimate things, he kicked a sofa to death, knifed his best hat, beat the face off a new lampshade, and drowned his bike. The last of which took place during the night as he was, again, cycling to work. As he approached Northam Bridge (over the River Itchen), the chain came off his bike (again). Convinced that his bike was being wilful, he picked it up and threw it over the bridge and down into the water.

Well anyway, that’s enough of that.

Getting to Know my Colleagues

My first impression of the blokes I was now working with was overwhelmingly positive. In three years I’d had some rough jobs, as well as working in a supermarket and the fish market, and never had I met such a decent bunch.

I distinctly recall as part of my local police training, learning first aid. In one of the first exercises I was to play the injured party. I can’t remember the nature of the pretend injury, but it entailed my trousers being undone. I recall that the enthusiastic first-aider pulled at my trousers so eagerly, as I played the unconscious victim, that my trousers were pulled low enough to leave my manhood displayed for all my assembled new colleagues to gaze upon. Not elegant.

Quickly, a heavily built officer came to my rescue. ‘Pig’ Bailey covered my willy with a blanket. (No, I don’t mean it took a whole blanket, merely that he covered me up, including my exposed parts.) What a bloke, what a kindly act.

I had a strange feeling of recognition when I squinted up at Pig (who his parents had christened Dennis). I had to ask him, ‘What part of Southampton are you from?’ ‘Harefield Estate,’ he answered. I knew immediately that this was the copper who had tried to stop our teenage gang when we turned a car over with the Hedge End boys inside. The punch-ups between rival gangs were frequent and fierce, but weapons were usually restricted to parts of the human body (I don’t mean any of us carried around a severed body part to use as a flail, I mean we only used fists, knees, feet and head). No one ever came armed with a knife or worse. Christ, I thought, I don’t want Pig telling everyone what a shit I’ve been. So I played it innocent – ‘Oh Harefield Estate, I lived in Harefield once too.’

Pig was still focussing on the first aid (of which he was a master), and to my relief wasn’t thinking of his new, keen young colleague in any other way except as in need of immediate support. He was fully focused on minimising the damage to my dignity. He was seeing the world from my perspective; I think that’s how he always was as a policeman.

After I had been a copper for a few weeks, a very well respected and fearless police constable (PC) and ‘thief-taker’ called Lionel Hutley visited our home. I think he was dropping some papers off for me to sign, I can’t truly remember, but he was visiting as a new colleague anyway. Mum was keen to make him welcome, so she served him tea and biscuits on a tray. But the tray belonged to Cunard Shipping, it was one of several items Dad had ‘liberated’ from the docks. Fortunately at the very last minute Mum covered it in a tea towel; we did have at least one that had not also been ‘freed from corporate service’.

Dad used to help himself to various bits and pieces from the docks from time to time. Sometimes it might be cutlery, sometimes chinaware. More frequently he brought home firewood or fish in his saddlebag. Like many dockworkers, he didn’t think it morally wrong to take from those who had considerably more – whether it was the Cunard, P&O, Union Castle or the British Transport Docks Board.

I hadn’t been a dock copper for long before I became aware that the docks police suffered from a sort of collective inferiority complex. The Hampshire Constabulary seemed to look down on us, or so it seemed. I soon realised that the Railway Police contingent of the British Transport Police looked down on the dock coppers too. Both were looked down upon by the Hampshire Constabulary. I learned later that the Hampshire Constabulary generally looked down on the Wiltshire Constabulary too, but were themselves, in turn, looked down upon by the Kent Constabulary. All of these both looked up to, and simultaneously down on, the Metropolitan Police.

This might seem inconsequential but it wasn’t.

Off the Top Diving Board

I did my three months basic police training at No. 6 Region Police Training Centre, Chantmarle, near Yeovil in Dorset. The centre served the police forces of Avon & Somerset, Gloucestershire, Devon & Cornwall, Somerset & Bath, Wiltshire, Dorset & Bournemouth and now for the first time, officers from the British Transport Police.

Thirteen weeks of abuse (not in the modern sense). The idea was for the police trainers to bully the recruits as much as possible in order to teach them how to bully each other and the public at large. During our first week, all new recruits (we were course number 200) were bussed to Yeovil and its Olympic-sized swimming pool. It always seemed strange to me that Yeovil would have an Olympic-sized swimming pool, I mean, they couldn’t really have imagined that the Olympics would come to Yeovil could they? Anyway, we all got changed (about sixty of us) and drifted out on to the pool edge, awaiting instructions. I couldn’t swim. Brummies didn’t learn to swim (there was nowhere for us to drown).

Sergeant Maurice was resplendent in his heavy-cotton tracksuit, Brylcreemed hair, white pumps and shiny whistle. His whistle screamed out and we all fell silent. ‘All right, all of you, swimmers and non-swimmers, off the top board.’ I felt my stomach turn. Suddenly my fear of heights met my inability to swim. How could I summon the courage to jump off the top board? How could I go home in disgrace? I couldn’t stand the shame of everyone thinking, ‘he lost his job ’cos he lost his bottle’. My father would have been ashamed of me. I would have been ashamed of me. I knew that if I didn’t follow Sergeant Maurice’s orders straight away, then my courage would fail.

I pushed my way through the crowd of mingling recruits. I was first to climb the ladders, up and up. I got to the top and looked down and out across the pool so far beneath me. It felt like I was in a Tom and Jerry cartoon, with the pool beneath me the size of a bucket and easily missed. If I jumped straight out forward I would never be able to struggle to the edge of the pool. It was too far. I knew I could manage about five or six strokes, but that was it.

I stepped back and ran to the edge of the board and jumped to the side, towards the edge of the pool. I hit the water about a metre from the edge; I guess I was underwater about three or four seconds. I came up and climbed out. I had jumped very near to where Sergeant Maurice had been standing. I don’t remember if that was deliberate. But I stood up and looked around. He had gone.

Within a few seconds the sergeant surfaced. His Brylcreemed hair, short at the sides and back, but long and swept back from his forehead a few seconds earlier, was now lying down across his face. He still had his whistle in his mouth, but now the pea was saturated. He climbed out, his heavy-cotton tracksuit now hanging very heavily. He had so much fury on his face. ‘What the bloody hell are you doing, constable?’ (He didn’t actually say constable, but it was a word that could be mistaken for an abbreviation.)

‘I can’t swim Sarge.’ Those were my exact words. He repeated them back to me with absolute incredulity. Now at this stage all the other poor buggers who couldn’t swim either, still thought they had to go off the top board too. I can clearly see the scene, even now. Recruits were very slowly milling about the ladders to the boards, most were silent, some were moaning to themselves, and then, clear as crystal, the only other man who had come with me from my home force, called out loudly, ‘Oh God, my back’s gone Sergeant, I won’t be able to climb up!’ The session was abandoned but not without a useful lesson for me. It’s amazing what people will do when sufficient social pressure is applied.

Police Training School was the first time in my life that I had actually studied hard. Lots of the recruits were grammar schoolboys; we even had the odd public-school type. The subjects were largely new to all of us, so we mostly started from about the same level of ignorance. I studied hard and enjoyed the sport. I got in lots of football and a little boxing.

Boxing was not an essential, or even regular, part of police training, but the equipment was there. When about 150 fit and active young men (I don’t remember there being a single female on the course) are all thrown together, a certain amount of pack behaviour, including the formation of a pecking order, is inevitable. So, the younger males competed to be alpha. This culminated in a boxing match between yours truly and one John Blackmore (county rugby player and ex-public school). John and I had got on well, but the old competitive spirit in both of us needed to be exercised.

John said to me, ‘Fancy a go in the ring then Graham, you and me, how about it?’ Now my boxing experience was extremely limited, a few lessons from Dad, a couple of tricks learned from the same person. Fighting in the street had little in common. But what was I to do? I said to him, ‘Okay fine John. I haven’t boxed for months now, but that’s okay?’

‘Months?’ he asked, looking a bit concerned now.

‘Yeah, it’s been a little while. But I’m game.’

‘Oh. Well I haven’t actually boxed much at all myself,’ he responded pensively.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll take it easy with you,’ I said back casually. Of course I was bullshitting, but even then I knew the power of impression. And he was impressed by my understatement and confidence.

That evening most of the students seemed to have gathered in the gym to watch the fun. John was as fit as I was, but taller and heavier. I knew my act had to continue to be convincing. I could see his confidence was low. The bell went for the start of round one and I danced out as if I knew what I was doing. I had my guard up, I snorted down my nose, and I threw out a left jab and danced away. John looked flat footed and worried. Gaining in confidence I danced in again and jabbed him with my left. I danced out again.