Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

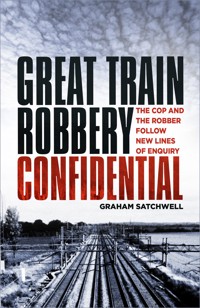

In 1981, Detective Inspector Satchwell was the officer in charge of the case against Train Robber Tom Wisbey and twenty others. The case involved massive thefts from mail trains – similar to the Great Train Robbery of 1963 where £2.6 million was taken and only £400,000 ever recovered. Thirty years later their paths crossed again and an unlikely partnership was formed, with the aim of revealing the truth about the Great Train Robbery. This book reassesses the known facts about one of the most infamous crimes in modern history from the uniquely qualified insight of an experienced railway detective, presenting new theories alongside compelling evidence and correcting the widely accepted lies and half-truths surrounding this story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 300

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Graham Satchwell served in every rank of CID within the British Transport Police (1978–99), for many years serving as Detective Superintendent, Britain’s most senior railways detective. During his service he was awarded numerous commendations by crown court judges and chief constables among others. This is his second book for The History Press.

Cover credit: View from a footpath near Ledburn, Buckinghamshire over the West Coast Main Line, towards ‘Sears Crossing’ where robbers took control of a mail train during the Great Train Robbery, 8 August 1963. (Sealman via Wikimedia Commons, CC SA3.0)

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Graham Satchwell, 2019

The right of Graham Satchwell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9346 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Lord Mackenzie

A Note from Marilyn Wisbey

Acknowledgements

Preface

One

Your Key Witness

Two

The Great Train Robbery

Three

The Crown v. Gentry & Others 1982

Four

The Railways: A Beacon for Thieves

Five

The South Coast Raiders

Six

Police Corruption

Seven

Meeting Tom Wisbey Again

Eight

Michelangelo or Mickey Mouse

Nine

The Mastermind and His Enforcers

Ten

Not One Plan but Two

Eleven

One Gang, Two Elements

Twelve

The Irish Mail

Thirteen

British Railways’ Response

Fourteen

The Signals and The Train Crew

Fifteen

The Robbers That Got Away

Sixteen

The True Insider

Postscript

Appendix 1: Letter from Mark McKenna

Appendix 2: Agreement with Tom Wisbey

Selected Bibliography

FOREWORD

BY LORD MACKENZIE OF FRAMWELLGATE OBE LLB [HONS]

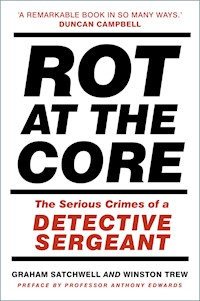

This is the third occasion on which I have written a foreword for a book by Graham. The first book was significant and led to his giving expert evidence to the United States’ Senate. The subject was counterfeit medicines and organised crime. That book exposed that vile international trade like no other had done before.

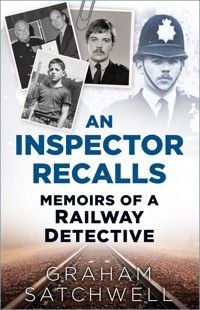

The second book was a memoir, which The Guardian described as ‘the best of the genre’.

This book is about the Great Train Robbery, which I have reason to remember well, as it occurred within only months of me joining the police service in 1963. It has the shared strength of both of its predecessors; it is conversational in style, amusing in parts and easy reading.

But this book also has the individual strengths of both aforementioned: it exposes Graham’s skills and drive as a very experienced detective, to uncover the truth about serious crime, but in the context of the sort of criminality that he personally confronted for over thirty years.

It is a testament to Graham that a notorious gangster, who was put away by Graham in 1982, was willing to work with him to find a way to tell the truth written here.

It is no surprise to me therefore that the book really does shed new light on the Great Train Robbery, as well as to correct an injustice perpetuated against an innocent man. Even though this crime occurred over fifty years ago, it displays the motivation, greed and destructiveness of criminality which is just as relevant today as it was in the swinging sixties. This book is a compelling read!

A NOTE FROM MARILYN WISBEY

I first met Graham Satchwell in 1981. I was about 27 years old at the time and my father had just been taken into custody for his part in handling some travellers’ cheques that had been stolen from the Royal Mail.

My mum and I went to a building in Tavistock Place, Bloomsbury to visit Dad. I remember it well because the place was nothing like a police station. It felt like an old hospital.

We met Graham at the lift and he was pleasant and polite. I remember that Mum said how handsome he was for a detective. Funny the things you remember.

They let me and Mum see Dad. They seemed to have treated him alright. But of course it was really bad that he had been arrested again; it meant he could be recalled to prison for the Great Train Robbery. He could have got another heavy sentence for the travellers’ cheques too.

Detective Inspector Satchwell, as he was then, objected to every bail application we made, and Dad stayed locked up for nearly two years awaiting trial. Dad never complained of course; he treated all that as par for the course.

I didn’t meet Graham again until after Dad’s stroke. Peter Kent, a friend to Dad going back many years, introduced Graham to me at the hospital. My dad and Graham had been writing a book together, not this one but a mix of fact and fiction, a novel. I’ve read the draft that my dad helped Graham with and it’s realistic. Obviously, both of them working together, you would expect it to be about right. It’s a good story too.

Graham visited Dad two or three times as his condition worsened. I remember once when Dad was fed up, Graham took him out in a wheelchair to give him a bit of fresh air and a change of scenery. Graham always treated Dad eye-to-eye, on equal terms. Dad was the same with everyone as well. That’s the way it’s supposed to be.

Graham has asked me an awful lot of questions over the last two years, many of which I didn’t know the answer to. I have been asking myself many of those same questions over many years. The process of working with Graham has helped me understand more of what went on. That might seem strange, but Dad would never tell me or Mum any more than he had to. He kept his work to himself – that was the rule and he stuck to it. But of course very occasionally I saw things, heard things, met people, took phone calls. It would have been impossible for me to have been kept in the dark completely, even as a child.

There are some big questions that remain unanswered. I would have liked to get closure on them all, but that will never happen now. But I have learned more recently about the involvement of the Sansom family, and I’ve been able to share what I know about the Pembrokes, Billy Hill, and so on. That’s been helpful to me.

And I’ve read the book that follows. I can’t add much to it. I don’t know any more than what’s there, and half of that I could not personally swear to. But it all makes sense and Dad had no reason to mislead anyone, not at that stage in his life anyway. There is a lot of truth in this book that has not been revealed before.

The Great Train Robbery made Dad very rich for a short space of time and famous forever. But it completely shattered our family. I would not recommend a life of crime to anybody. A lot of young blokes like the glamour and the reputation that they think that sort of life will bring. And that way of life means you don’t have to commit to working most days of your life. You never have to set an alarm clock and if you’ve got your head screwed on, the money is good as well.

But most men and women want more than that. They want trusting, loving relationships, family and peace of mind.

I definitely do not recommend a life of crime.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First, I must acknowledge the help given by Tom Wisbey. There have been many sources for what follows, but undoubtedly the most significant was the train robber Tom Wisbey.

Before 2014, Tom Wisbey simply knew me as the former detective who led the case that resulted in his being re-imprisoned in 1981. In 2014, I discovered we had a mutual friend, a very discreet, elderly gentleman called Peter Kent. Peter arranged for Tom and me to meet and when we did, Tom readily agreed to help me with my Great Train Robbery book. He put himself out to help me and continued to do so for several months before the stroke that led to his death. I will say much more about Tom later, but it is certainly the case that without his input this book would be much less than it is.

After Tom’s death, his daughter Marilyn was kind enough, for over two years, to help me make sense of some of the things that Tom had told me. I thank her for that.

I think I understand for the first time in my life why some books contain acknowledgements pages that provide a cast long enough to typify a Hollywood movie. I know now that some books really are thanks to the contribution of many. This is one of them.

The British Transport Police History Group, which is made up chiefly of retired BTP officers, was helpful in giving access to papers that they held and for appealing for information.

When this book was almost fully drafted I encouraged the participation of Channel 4 TV. They were extremely determined to check out my background. I put them in contact with two men that I worked with in the early 1980s: Martyn Leadbetter, a national figure in the world of fingerprint evidence, and former Detective Sergeant Peter Bennett (Met Police C11, NSY). Both men were keen to help, and both recalled important aspects of those days, some of which I had forgotten and which were important to the story.

Members of the same Channel 4 crew were determined to test my assertion that a certain handwritten note was written by Tom Wisbey. Obviously, I do not have access to forensic science these days, so I must thank Amanda Langley, fingerprint expert at the City of London Police for her great help and hospitality.

I know little of the rules of railway signalling and I am indebted to David Smith (formerly a high-ranking rail professional of many years’ standing) for his insight and for sharing his considerable knowledge of the railways of the early 1960s.

Early in 2019, I wrote to the railways’ staff pensioners’ publication Penfriend and they kindly published an appeal for information about the robbery. The response was tremendous and a thank you is owed to the editor and all those fellow ‘old folk’ who took the time and trouble to get in touch.

Much of what they told me was of value, and all of it was very interesting. Leslie Watson from Cardiff became my instant expert on the realities of being a train driver in the early ’60s. Tony Glazebrook helped me tremendously with a copy of the BR Internal Enquiry papers given to him a few years after the robbery. Nigel Adams (Luton Model Railway Club) and Geoffrey Higginbotham (former TPO worker) were both helpful and entertaining. Lindsey Bowen, Bill Faint, and Malread Harvey also deserve my thanks.

John Tidy joined the BTP at the same time as me but after a couple of years had the good sense to leave. A few years later a successful career in publishing led him to the USA. I’m pleased to say that he resettled in the London area relatively recently and helped a good deal with research for this book. Thank you, John.

Similarly, I was delighted to speak to several other old BTP colleagues including former PC Gordon Blake, who was on duty on the night of the Great Train Robbery and awaited its arrival at Euston station. Similarly, Stan Wade for his important contribution and with whom I worked as a young constable (more of him later) and Eddie Coppinger who also remembered 1963 and served in the British Army with one of the train robbers.

Peter ‘Chippy’ Woods, a very long-since retired detective inspector now living ‘Up Norf’, made contact with me for the first time in well over thirty years. He knew Buster Edwards and made the tea (as a young detective) for the CID bosses engaged in the investigation. More significantly, as part of the specialist mailbag squad of the time, he investigated some of those crimes committed by the South Coast Raiders.

Of course, there are others too: John Wyn-De-Bank, Peter and Stephen Kent, Colin Boyce from Thames Valley Police (who kindly allowed me to reproduce a couple of photographs) and Paul Bickley at NSY are chief amongst them.

Arwel Owen, son of the guard who was assaulted by the robbers six months before the Great Train Robbery, played a very important role in uncovering the truth. Several years ago, Arwel wrote an excellent book describing those events and when I approached him this year for the first time, he was extremely accommodating.

In later chapters you will see important photographic evidence, but without the staff of Bournemouth Newspapers that evidence would have been lost and so my thanks to them for their very necessary help.

But when it comes to moving from a draft book to a publication, things get really tough. Thank goodness for The History Press and editor Amy Rigg. Amy was so encouraging, consistent, positive and constructive; she could not have made the process easier.

PREFACE

The story of the Great Train Robbery (GTR) has surely been told, retold and embroidered as much as any crime in history. Anyone coming to the subject for the first time and reviewing the materials available would be left misled and confused. However, it is easy to point back to facts proven beyond question, facts readily accepted by all concerned, and where such evidence is not available, overwhelming logic. In addition to stripping back the mass and mess of misleading assertions to a coherent truth, I have discovered much that has not been revealed before.

The GTR took place in 1963. To fully understand the public response it is necessary to appreciate that different social norms operated. A firm and undisguised class structure was in place. Those who had real financial or political power had their own vocabulary and spoke naturally with, or affected, a particular accent. That accent was somewhere between that required of a BBC commentator and a member of the Royal Family. Such people dressed in a way that was exclusively theirs; they had foreign holidays, motorcars and particular leisure pursuits, went to university, and did particular jobs that were exclusively theirs. It was a fairly rigid class system in which everyone was ‘supposed to know their place’.

Today of course, that world has been turned on its head. Politicians try to disguise their public-school accents, money rules no matter how it was gained, everyone has a ‘motor’, princes drink beer and foreign holidays are given to people ‘on benefits’. But by 1963, the winds of change (to use a phrase of the time) were blowing gently but building. The ‘common man’ (and I was a very young one at the time) felt rebellious: ‘Why should I be expected to show deference to people who just happen to have been born into money?’ That societal change is only important in this context because it reflects the two different ways that the robbery, and the robbers, were viewed.

The basic facts are well known. On the night of 7/8 August 1963, a gang of about fifteen held up a mail train that was making a routine journey from Glasgow to London Euston. The train concerned was a mail train known as a ‘travelling post office’ (TPO). It had no passengers but about 100 postal workers. They busied themselves sorting the mail as the train sped through the night. The two lead coaches held about £2.6 million in banknotes of various denominations (being returned to the Bank of England for cleaning or destruction).

The TPO train made its usual scheduled stops (to pick up more mail), the last of which (before London) was Rugby. At Rugby, the train crew who had brought the train down from Scotland finished their duties. Driver Mills and Second Man Whitby replaced them. The train left Rugby on time but near a quiet spot called Ledburn in Buckinghamshire it was attacked.

The robbers stopped the train just south of Leighton Buzzard by altering two trackside railway signals. The driver had fully expected to have green lights all the way, but one of the robbers, Roger Cordrey, was highly skilled. With an accomplice, he ensured a trackside signal was changed to yellow (or amber), indicating ‘caution’. This would cause the driver to slow right down and prepare to stop. The second false signal was red, and Driver Mills immediately brought the train to a stop at the signals at Sears Crossing.

As soon as the train stopped the robbers busied themselves disconnecting the locomotive and front two coaches from the remainder. They overpowered the driver and his assistant (Second Man) and divided the locomotive and two ‘lead’ coaches from the rest of the train. Having separated the train into two, the robbers forced the train driver to move the locomotive and two coaches forward to Bridego Bridge. There the gang smashed their way into the coaches and set upon and subdued the postmen working within.

The robbers unloaded about 100 mailbags from the train and made off with over £2.6 million in untraceable used banknotes. Only just over £400,000 was ever recovered or accounted for. The whereabouts of the rest has remained a mystery.

It is generally believed that three of the robbers who attended the train that night were never caught. It was by far the biggest robbery ever committed in Britain. The Establishment expressed indignity, outrage and a determination to punish. Following the trial at Aylesbury, sentences of up to thirty years were imposed. Those sentences were immense; they were double the length that one would expect to receive if convicted of committing an armed robbery and discharging firearms. Any policeman or lawyer at the time might have anticipated a sentence of perhaps ten to fourteen years. The response to those sentences was largely twofold. The Establishment, as you will see later, was determined to bolster the case against the accused, and after the sentences were meted out, equally keen to justify them. Conversely, many of the general public began a sort of celebration of the robbers who it seemed had stolen from those that could afford it using minimum force. For many it seemed as if Robin Hood and his Merry Men lived again.

Certain members of the Establishment went overboard in their determination to punish and vilify. Records of events after sentencing are remarkable, as you will see later, in the stories told by those in authority about the threat that such a major crime held against society in general. This of course merely painted establishment figures even more vividly as part of the ‘Sheriff of Nottingham’s gang’. You will see how these two very different interpretations of events have coloured both the evidence at the trial and what has been written and said since.

No one has ever stood trial for being the organiser, and no one has ever stood trial accused of supplying the very necessary inside information. From the earliest days after the robbery, there have been all sorts of outlandish accounts of who the missing robbers might have been. There have been even more ludicrous stories ‘revealing’ who orchestrated it all. The creation and dissemination of all that guff has been caused by an undeserved (and unpaid for) desire by shallow individuals seeking fame and infamy. In addition some professional writers and broadcasters have seemed keen to get a story at almost any cost to their own integrity and greater cost to the innocent. Then there were the robbers themselves, determined to make a buck and to add to the number of individuals keen to buy them a drink or a meal.

If you read any reasonable selection of books about the robbery, you will soon discover that certain key facts have remained open to speculation. These include:

• Was there a mastermind?

• Who was the key insider who gave the vital information to the robbers?

• Who were the robbers that got away?

This book sheds new light on those key areas, not by empty speculation but by evidence and logic. In doing so, it debunks some of the nonsense that has been commonly believed, for instance that Bruce Reynolds was the leader of the gang, that the robbery was planned during the summer of 1963 and so on. Incredibly, it is the first proper review and investigation of the facts by a senior detective who has no vested interest in holding up the initial investigation as full or complete. The assistance of one of the train robbers has added greatly to that process.

ONE

YOUR KEY WITNESS

Much of what follows requires you to suspend belief in the integrity of the police in the late 1950s and early ’60s, the nature and extent of violent crime during that period and any long-held conclusions about the Great Train Robbery (GTR). Your doing so will depend on your thinking me a credible witness. Here is my brief CV.

I was brought up on council estates in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s and had a working-class childhood. I left school without any qualifications and as a ‘nearly’ professional footballer, took various labouring jobs on building sites.

All the teenagers I hung out with had criminal convictions. One later committed suicide in prison at a young age, having killed his wife; another was sentenced for armed robbery. I smoked pot, popped a few pills, got into scraps and got drunk too often. That was all very typical of someone from my background.

Nearing my 19th birthday and having met a ‘straight’ and beautiful young woman, I decided I needed to change my ways in order not to frighten her off. No more drunkenness, drugs, or silliness. I joined the Transport Police at Southampton Docks. I scraped in.

I had never studied before, but now I had to. Failure to pass the necessary police exams would have meant my being ‘required to resign’. That was an outcome I was determined to avoid at all cost. Exams aside, I achieved an excellent arrest record and was moved into CID at the remarkably young age of 21.

I was promoted to sergeant at the age of 23 and transferred to London. From there I was gradually promoted up to the rank of detective superintendent, aged 42. There I stayed.

By the time of my retirement I had received numerous commendations from Old Bailey judges, chief constables, and one from the Director of Public Prosecutions as well as the thanks of about three government ministers.

I formed two public charities and was the main author of the first ACPO Code of Ethics for Policing and one of the writers of the ACPO Murder Manual (the bit on corporate killing).

I led many high-profile investigations and was a Director of Studies at the National Police Staff College, Bramshill. I won two scholarships to university and was invited to apply for a Fulbright Scholarship to the USA.

I served for eight years as the detective superintendent for British Transport Police (BTP) and was head of CID. In that capacity I received, many years after the first, a commendation for my part in the detection of an organised gang of dangerous mail train robbers following a multi-million-pound theft.

The record shows that I took on police corruption head first. Before retiring, I received police long-service and good-conduct awards. Frustrated at my bosses, I left the police service as soon as my pension became payable at 50. I immediately joined the Microsoft Corporation in a senior capacity based at its European headquarters in Paris.

After that I had a series of senior corporate positions including director at the world’s second largest pharmaceutical company, GlaxoSmithKline. Before leaving there, I was highlighted for promotion to vice-president. During that time I conducted significant international investigations into organised crime and the counterfeiting of medicines.

I have had two books published, the first on counterfeit medicines and organised crime. That led to my giving expert testimony before the United States’ Senate. The second, a memoir, was described in The Guardian as being, ‘The best of the genre’ (police memoirs). I am a law graduate and Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. I have been married since 1968.

TWO

THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY

Tom Wisbey told me that if everyone who had claimed to have taken part in the robbery, or been invited to, were to get together, you could fill Wembley Stadium.

We have had many GTR books and films claiming ‘exclusive’ access to the truth, but many are pure fantasy. More recently we have been expected to believe that Bruce Reynolds was the ‘Mr Big’. In reality, as I will show, he was perhaps more ‘Mr Big Ego’.

Within hours of the robbery, the Post Office publicised a £10,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of those involved. In addition, the loss adjusters for the banks offered £25,000.

That was enough to buy seven family houses in London. Can you imagine what professional informers, casual ‘grasses’, other thieves, bent coppers, ‘cheeky chappies’ and various chancers would have done to get a share of that?

Take a simple example that might ultimately have led to a great deal of trouble. In an official memorandum, which seems to have been taken very seriously by the Post Office Investigation Department and their bosses, information which they have received states:

At 9.10 p.m. on the 8th August (1963) an open Mini bus drew up outside 99, Pollards Hill South, Norbury … It contained about thirty pillowcases – stripped [sic] ticking – and each of them was filled with something or other and each had its neck tied with string or rope … Two men were in the (open topped) mini-bus and … the men took the pillowcases, together with some sacks or bags, into the house.

Apparently, this was regarded as significant because the informant knew that the woman who lived in the house had at some stage been a prostitute. As if that wasn’t enough to seal her fate as part of the GTR gang, the informant reveals that ‘she once lived with a man who was convicted of violence’!

The apparent intrigue deepens: ‘There are two friends who call frequently at the house – a blond woman and a balding man, middle-aged.’ The official memorandum is concluded with the solemn instruction, ‘We would look into the possibility that the pillow cases might have contained some of the proceeds of the mail train robbery.’ It is signed by a C. Osmond.

Now, you might think it ever so slightly unlikely that the implications of this would be taken seriously. That, having pulled off the biggest robbery in history just a few hours earlier, and with news of the event being broadcast every hour into homes across the country, the bone-headed robbers have loaded the money into pillow cases and conveyed it across London in an open-topped vehicle.

You might think it sounds like part of a script for an Ealing comedy. But does that stop the intrepid Post Office Investigation Department Controller taking this nonsense seriously? Clearly not. And worse, does it stop him from taking the story to a meeting with Metropolitan Police Commander Hatherill and various chief constables and the most senior police investigators? No.

But taking the issue seriously does provide the notion of someone in Norbury being involved, as well as a middle-aged balding man and a blonde (you could never trust a blonde in those days; all blondes were by definition and common consent ‘hussies’).

Many years later, the description of a middle-aged balding man with a connection to that part of London was resurrected and built upon by Gordon Goody to result in the false identification of the man who gave the necessary inside information. He was thereafter called the ‘Ulsterman’.

To be clear, I am not saying the unlikely tale of the ‘30 pillow cases with stripped [sic] ticking’ should have been ignored. No, first it should have been evaluated and then prioritised (as non-urgent). Instead of that, as is clear from the records, it was treated as very significant and urgent. The result seems to have been numerous wasted man-hours.

When the first draft of this book was nearly complete, a journalist read it and checked references for me. He found in one of the books I had referred him to, reference to the ‘30 pillowcases full of money’ story, and chose to accept it without question. He thought it must have been a significant investigative lead. A few days later when we met I asked him if he really thought anyone with half a brain would ever think it was a good way to transport a huge number of banknotes, particularly in those circumstances.

He responded by saying that the words ‘pillowcases’ had not been mentioned at all in the book referred to; instead it referred, he said, to ‘bags or sacks or something’. He went on to say that no open-topped van had been mentioned either. He was 100 per cent wrong.

However, I’m certain he was not trying to deceive me, so what was going on? Nothing more I think than a subconscious desire to accept an underlying theory that would have been useful for his purposes, rather like that Post Office official, Mr Osmond.

Writing this book entailed reading as much as I could about the subject and then stripping away as much nonsense as possible. That process has helped me to ignore conventional and accepted conclusions and bring out the truth. Some of that has been easy to do, some of it very hard. One strong example is the position of the much respected and admired Train Driver Mills.

For many years I fulfilled the role of senior investigating officer in cases involving serial rapists, homicide, kidnapping, armed robberies and other serious crime. There is always a need to take the same fundamental approach. It is to start with the false assumption that anyone could have committed the crime. No one is too cherished, too rich, or too powerful to be presumed incapable.

The most perfect example in our case would be to consider whether the train driver, his Second Man (assistant), train guard or signalman on duty in the relevant signal box were criminally involved. Hard to believe though it is, this does not appear to have been the case in 1963. It is a particularly sensitive matter in relation to Driver Mills, but you will see the outcome is not straightforward by any means.

As a result of the above, this book sheds fresh light on key issues in the case and provides a fresh perspective. I have not performed a proper ‘cold case review’ (my resources are now restricted to a single set of less-than-perfect eyes and my knowledge of police procedures are twenty years out of date). But if this were a formal review then there is no doubt that ‘fresh lines of enquiry’ have been revealed.

I was a railway detective for a long time. I saw and heard a lot of things that you will think improbable. There were policemen who would routinely steal, ‘fit people up’, and one or two who were even prepared to kill – and I mean murder other policemen or criminals who stood in their way. ‘Murder other policemen’; that sounds fanciful, but I personally came across ‘threats to kill’ on two occasions, once within the Metropolitan Police and once within my own force, the Transport Police. In neither case was there ever an official investigation.

Telling you that, in the 1960s and 1970s, some detectives from the Met were corrupt will not surprise you. Some got rich, but that shouldn’t be news to you either. What you might not know is how that corruption in the London police forces (Met and City of London) extended to the Transport Police and, of course, beyond.

In the late 1970s a number of detectives from the Transport Police received long prison sentences for organising the theft of lorry loads of goods from the Bricklayers Arms Depot in South London. Not long before, a senior detective had been punished for doing likewise at the railway yards in Stratford, East London. I mention that now because shortly I will be asking you to consider a railway policemen was involved in the GTR.

The Great Train Robbery has entered folklore as the story of likeable rogues who used cunning and daring to get rich and get one over on the State in a largely non-violent way. These days the media describe the perpetrators as (variously) hairdressers, florists, carpenters, window cleaners, club owners and bookmakers. I think at least some who have made those claims have done so honestly but, more importantly, in complete naivety.

Yes, the robbers created such nominal occupations for themselves. Gordon Goody did have a hairdressing business. Roger Cordrey did run a florist’s shop, Tom Wisbey had a bookies and Bob Welch, for example, had a nightclub. I am even prepared to believe that Jim Hussey cleaned the odd window (but not often). Essentially, these adopted occupations were firstly to provide an ‘excuse’ for having money in their pockets. Secondly, when arrested or put before the courts, it gave the impression that they were something other than professional lawbreakers.

The mythology surrounding the robbery has largely been written by the popular press. It has been created and added to by the robbers themselves, their families and sycophants. But it might also have been fuelled by those with an interest in holding onto any remains of the outstanding fortune; after all, the vast bulk of the money is still missing – in today’s terms there is still over £40 million missing.

According to myth, the train robbers belonged to the days when villains were ‘honourable’ and policemen were ‘honest and upright’; professional villains generally left ordinary people alone; ‘good’ villains never informed on one another and they rarely used violence. In that mythical world, violent crime was hardly ever encountered. A quick look at the current extraordinary levels of knife crime tells a different story. Levels of stabbing have not been as high as they are now since the 1940s and 1950s.

Similarly, the use of firearms in the furtherance of theft is today nowhere near the level it was in 1950s and ’60s. And it is the same with ‘murder in the furtherance of crime’ (leaving aside acts of terrorism).

At the same time during that mythical halcyon period, policemen were honest, upright, trustworthy individuals. They would never tell lies in the witness box. They would never take bribes. They were almost invariably dedicated public servants who thought little for their own health, wealth or safety. It was apparently a world of Dixon of Dock Green and thieves who would mutter ‘It’s a fair cop guv’ at the mere sight of a uniform. There might be some comfort in seeing the world of our youth in that way, but it truly never was like that.