Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

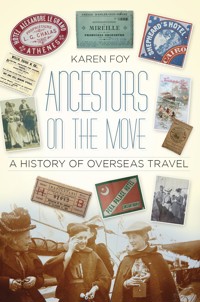

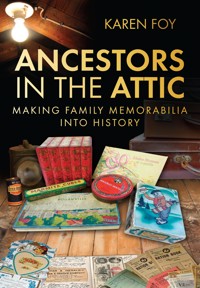

Much family history focuses on digging around archives and web searches. Here, Karen Foy shows that our attics and cupboards can often hide a treasure trove of personal documents and ephemera. Boxes full of photographs, hastily written notes, old tickets, postcards, ration books, a soldier's hat, a bundle of letters, perhaps a diary, are all invaluable sources of information about our family history. These are crucial in piecing together the everyday lives of our ancestors, exposing secrets, and family relationships. You might discover favourite family recipes, information about their schooldays, reconstruct a Victorian family holiday. This book guides you through 200 years of different types of memorabilia: how to interpret them and how to use them to make your own family history – perhaps making a scrapbook or website.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Jeff – Love Always. With thanks for your support, encouragement and honest opinions during my latest venture. This one’s for you!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to The History Press for giving me the opportunity to write another book. I have enjoyed the research as much as the writing. Thank you to Stewart Coxon for providing some excellent images for illustration and for those kindly supplied by The Advertising Archives and Mulready Philatelics.

Writing and research can be a time-consuming and intensive profession requiring dedication to overcome regular writerly hurdles. I’ve often found that it wouldn’t be possible without the support and encouragement of family and friends, so thanks to you all, and especially to my husband Jeff for his regular ‘words of wisdom’, my auntie Margaret Turner and my mother-in-law Marjorie Martin for ‘spurring me on’, and Enid Jones, unofficial ‘agent’ and friend, for her unwavering interest in my work.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

ONE

Putting Pen to Paper

TWO

Travel and Transport

THREE

A Stamp of Approval

FOUR

Reading Between the Lines

FIVE

Regulations and Restrictions

SIX

Setting the Scene

SEVEN

Customers and Commerce: Letterheads, Bills and Receipts

EIGHT

Artistic Advertising

NINE

Photography

TEN

Events, Entertainment and Opinions

ELEVEN

A Lasting Reminder

TWELVE

Changing Fashions

THIRTEEN

Decorative Essentials: Accessories, Jewellery and Watches

FOURTEEN

Habits and Hobbies

FIFTEEN

Sporting Memorabilia

SIXTEEN

Kings of the Road

SEVENTEEN

Playtime and Pastimes

EIGHTEEN

Household Essentials

NINETEEN

Checklist

Auction Tips

Useful Websites

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

For the majority of family historians, once you have dipped your toe in the water of this fascinating pastime it is very hard to stop researching. The compulsion to find out more takes over and then you’re well and truly addicted to this genealogical world.

Perhaps you recognise the scenario: you have endless lists of names, dates and places stored in files or on your dedicated computer program along with a whole host of neatly accumulated birth, marriage and death certificates relating to the most significant members of your ancestry. Transcripts of parish records threaten to spill from your folders and you’ve spent many enjoyable hours investigating family occupations that have now become long-forgotten trades.

Although your tree has branched out to encompass distant cousins, the quest for new names becomes more difficult the further back you go. Perhaps you simply feel that you want to concentrate more on those ancestors who are closer to you. If you’ve read my previous book, Family History for Beginners (The History Press) you may have gone down the route of preserving your findings in a variety of ways to share with your family, but like all historians, you are eager to go that one step further in finding out about your ancestors’ lives. For me, this next stage is to look more closely at the physical evidence they left behind and build a bigger picture of life in a particular period by discovering what people wore, the items they used to decorate their homes, ephemera collected from memorable events, as well as letters, photographs and journals that document an individual’s thoughts, feelings and hopes for the future.

It is time to step inside our ancestors’ shoes in an attempt to learn more. At the beginning of any genealogical journey I always advise new starters to dig out all their family memorabilia to see what clues they may hold to their heritage, but as the pursuit of names and dates takes over, these items often get pushed aside as you become absorbed in the research. Now, along with the mass of information you have already collected, it is time to re-examine those items and reveal their secrets.

This quest for knowledge is all about looking at the evidence from a different angle. A photograph that initially may have meant nothing to you could now hold the key to a family puzzle; items in the background of the image could still exist and be residing in a relative’s cupboards. An indenture or mortgage document relating to a property that you thought had no connection to your forebears could, in fact, have been the childhood home of one particular branch of your tree. Sporting trophies, clothing, accessories and childhood games may now be attributed to an individual, and a diary entry of a trip abroad relating to what at first seemed like a bunch of strangers could spark recognition.

You have now taken on the role of your family’s ‘lost and found’ department and your mission is to find out more about the items that have stood the test of time but may be living in your attic or those of other family members.

This task also has a dual purpose. Perhaps you may not have been fortunate enough to have inherited many items from your ancestors. If that is the case, the wealth of antiques, collectables and ephemera available today from fairs, car-boot sales, specialist auctions and internet websites will allow you to build your own dedicated archive. Seek out an example of the type of newspaper an ancestor of yours is likely to have read in 1880 and discover what was happening in the world at that time. Perhaps family photos show a female ancestor who was never seen without her elaborate tortoiseshell hair accessories or elegant shoe buckles; why not track down some similar period examples to add to your archive, enabling future generations to touch and examine the fashion items of the past?

Uncover the treasures that were once part of everyday life and discover that each and every one has a story to tell. Combine your tried and tested research skills with the physical evidence before you. Take a second look at those ‘ancestors in the attic’ and you may be surprised at what details can be brought to light. Learn more about the history that surrounds some of these objects with help from the various in-depth ‘Step Back in Time’ sections in this book and discover their significance in your forebears’ lives. A wider knowledge leads to a better understanding of events or the reasons behind an individual’s actions.

Enjoy building that bigger picture and you’ll soon begin to realise that investigating your ancestry can turn into a long-term project where the possibilities are endless and only limited by the boundaries you set.

CHAPTER BREAKDOWN

1. Putting Pen to Paper

Diary keeping, its aim and purpose. Famous diarists. How thematic examples, such as war diaries, personal accounts of everyday life and occupational diaries, can aid the family or local historian. Almanacs, their history and their importance to farming communities.

How to use diaries to build a picture of what life was like during different periods. How to track down themed examples to aid research. Investigation and preservation techniques.

2. Travel and Transport

Investigating travel-related ephemera. Understanding travel journals, their mention of varying types of transport, from sailing barques to steam trains, and the locations visited during Grand Tours. Discovering the reasons why people travelled. Britain’s first travel agent, Thomas Cook, his organisation of day trips and global excursions. The Temperance movement, understanding its purpose and the ephemera and propaganda produced. The history and traditions of British seaside holidays and the related memorabilia produced.

3. A Stamp of Approval

Understanding the history of the postal and stamp system. Examining different letter, envelope and postal formats. Victorian correspondence, essential etiquette.

4. Reading Between the Lines

War-related ephemera. Enhancing your military investigations with medals, badges, buckles, tags and war propaganda posters. Embroidered postcards produced, especially during the war years. Military memorabilia and media coverage.

5. Regulations and Restrictions

Home front memorabilia. Understanding this period in history. Investigating why each item was issued and the restrictions they would impose upon our ancestors’ lives. The role and related ephemera of the Home Guard, ARP Wardens and Women’s Land Army.

6. Setting the Scene

Understanding the history of map-making. Topographical and local-interest ephemera. Maps, walkers’ guides, directories, street plans, leaflets and tourist pamphlets and posters. Understanding more about the area and places of note in the locality where our ancestors lived or the destinations to which they travelled.

7. Customers and Commerce: Letterheads, Bills and Receipts

Indentures and apprenticeships: did your ancestor leave evidence of a trade? Business stationery, including letterheads, ledgers and receipts. Trade journals and occupational memorabilia. Prosperity or poverty: what clues can this type of ephemera provide? Investments: stocks and share certificates, mortgages and legal documents. Using legal documents to further your research to discover names, addresses, specific locations, trading names, land and property ownership.

8. Artistic Advertising

Business promotion, the ephemera that binds customers and commerce. Trade cards, advertising and promotional packaging. Uncovering your ancestors’ likes and dislikes, shopping and eating habits.

9. Photography

The development of photography. Recognising photographic procedures. Dating dilemmas and identification problems: how to close the net. Photo storage and preservation.

10. Events, Entertainment and Opinions

How greetings cards can confirm family relationships and ages. Popular period entertainment. How newspaper cuttings and reviews, theatre programmes and show-business publications of the day can enlighten us about the music, theatre, books, famous personalities and events that our ancestors enjoyed. Suffragettes; following our ancestors’ political beliefs.

11. A Lasting Reminder

Using newspapers to widen your genealogical research and understanding of life during a particular period. The history behind publications such as The Illustrated London News, The Sphere, The Graphic and Punch. Where to find these publications; the importance of this type of resource and how to preserve it.

12. Changing Fashions

Iconic clothing and fashions through the decades from the Victorian era to the 1920s, continuing to the Second World War, and their ability to help you to date your photographs. Mourning robes and their meaning. The Victorian wedding dress; choosing the right colour fabric. The christening gown; the importance of lasting legacies. The preservation and storage of fabrics.

13. Decorative Essentials: Accessories, Jewellery and Watches

Decorative accessories that were deemed important enough to our ancestors to bequeath to future generations. Hair combs and the styles they embellished. Parasols and umbrellas. Buttons. Beaded bags and how to date your examples. Lockets and love tokens. Perfumes, the decorative containers used to house them and their significance to our forebears. Masculine embellishments; timepiece identification, walking canes and decorative cufflinks and pins.

14. Habits and Hobbies

Smoking and smoking collectables. Sewing boxes, lace-making, embroideries and tapestries, quilting and patchwork; the history behind them and the clues they can give us.

15. Sporting Memorabilia

Medals and trophies awarded at sporting events may hold the key to your ancestors’ past. Sporting almanacs. Cigarette cards. How to build a sporting archive.

16. Kings of the Road

The popularity of the motor car from the end of the nineteenth century. Was your ancestor a keen motorist? Discovering why motoring manuals, price guides and publications, as well as advertising and apparel, could help you build a bigger picture of their passion.

17. Playtime and Pastimes

Childhood toys can reveal a great deal about our ancestors’ youth. Consider what their games can tell us about their personalities and upbringings. Which games were popular during which era? Determine how education and religion featured in some toy themes.

18. Household Essentials

Learn how the simplest of household objects can throw light on the daily lives of our ancestors. Customs and traditions within the home and the history behind them.

19. Checklist

ONE

PUTTING PEN TO PAPER

Writing is an exploration. You start from nothing and learn as you go.

E.L. Doctorow

Rifling through the personal possessions of deceased family members can often seem like prying, but it is surprising how many long-forgotten secrets you can discover, or which unanswered questions you can solve. Any number of items could have been handed down within a family or bequeathed as a lasting legacy, it is just that some pieces of memorabilia, ephemera and what are now today’s collectables, tell greater stories than others.

If you’re lucky enough to unearth a personal diary or journal then you really have struck gold. Used to record a person’s innermost thoughts and feelings, as well as to chart the year’s events and daily activities, this is one of the few opportunities that you’ll have to really get inside your ancestor’s mind.

HISTORY IN THE MAKING

From great historical writers such as Samuel Pepys and Dr Johnson to the wild and imaginative jottings of the fictional Adrian Mole, keeping a diary has been a popular pastime for thousands of people throughout the centuries. Samuel Pepys, Britain’s most famous diarist, was born in 1633 and went on to become an MP and naval administrator while keeping a detailed private journal from 1660 to 1669. His jottings provide witness accounts of fascinating events during this decade, such as the Great Fire of London and the effects of the plague, but also offer personal details that we could never hope to find in a history book.

Diary keeping became increasingly popular from the seventeenth century onwards with many factors contributing to an interest in this pursuit of recording memories. Advances in the education system saw a growth in literacy among the population, and those with religious beliefs began questioning their faith. Others chronicled the births, marriages and deaths of family members, describing these events in detail for future generations. This was an era when paper production became cheaper and more affordable for personal use, allowing the diary to become a sanctuary for the author’s thoughts and observations.

Thoughts and feelings can be found written in the hand of an individual in personal diaries, providing priceless information that you could not hope to find elsewhere.

There is nothing quite like the excitement of discovering a diary, or any form of personal correspondence that has been lovingly stored away for decades in an old chocolate or cigar box that obviously meant so much to the original owner that they felt compelled to keep it. Regularly disposed of as just the personal trappings of the deceased, any such writing that avoids being tossed out with the rubbish or lies hidden for years only to be discovered by an enthusiastic benefactor can form part of a fascinating collection – priceless to a descendant – but can also provide an intriguing glimpse into a particular period of time, which can aid your own investigations.

THE ORGANISED APPROACH

The following tips can be applied to your study of any type of correspondence, not only diaries:

★ Always read the document through once to get a general idea of what it contains and then, with a critical approach, take a closer look at what you’ve got.

★ Note down all the facts, dates and addresses, along with any assumptions that you may have made.

★ Add descriptive information about the interior of the writer’s home, the car they drove or even the clothing they were wearing at the time.

★ Log any questions that need answering and future avenues of research that you can pursue.

★ Keep all your notes, even when you’ve found the answers, as they are always helpful to refer to at a later date and may inspire another train of thought for you to follow.

From the rich to the poor, the agricultural labourer to the lord of the manor, a diary and personal reminiscence can transport you back in time.

Ask yourself:

★ Is the diary themed, for example, an occupational aid used to jot down the notes of a lawyer or doctor. Is it a war diary recollecting the feelings of someone involved in a conflict, or the recorded travel exploits of the family adventurer (see Chapter 2)?

★ Was the diary created solely to record a specific event or period? Why was this important to the writer?

★ What does it tell you about everyday life at the time?

★ What kind of relationship did the writer have with their family? Did they have a happy marriage, or was their diary keeping a means of escape from a trapped or unhappy relationship?

★ What was happening in the world at the time? Did the writer mention world events and, if so, what was their reaction to them?

★ Did the writer have aspirations, ambitions or hopes for the future and were they ever fulfilled?

★ Look for additions and inclusions: memorable items that the user thought important enough to paste between the pages. These could include sketches, verses, sentiments, tickets, postcards and other paper ephemera. Take a closer look, what can they tell you?

Top Tip

Where diaries are written in a plain notebook and only the day and month dates are recorded, use an online calendar calculator such as http://easycalculation.com/date-day/dates.php to try and pinpoint the year in which it was written. N.B. The same technique can be used on other letters and documents where the specific year has not been noted. Recorded events within the document may also help to provide a time frame.

PRESERVING THE PAST

Where possible make a copy of the document: this will save on wear and tear during your research. Use a photocopier with an adjustable panel that allows the copying of larger diaries to ensure that the spine is not bent, broken or creased. Store copies away from the originals so that if one becomes lost or damaged you will always have the other.

Keep items in as near perfect condition as possible by storing in a cool, dry place out of direct sunlight. Wrap in archival paper, which is acid and lignum free to help with long-term preservation, and if the item is extremely delicate consider wearing cotton gloves while handling.

Paper ephemera can rip easily and after years of being folded in a certain way, may become fragile along fold lines. Contemplate transcribing entries that are difficult to read onto your computer, to help make future reference easier.

Never write notes – even in pencil – on your original copy and don’t cut or remove any loose pieces, always keep everything original together.

Find Out More

A diary does not have to have belonged to a member of your ancestry to add background information or understanding of a particular period to your family tree. There are literally thousands of manuscripts, letters and documents up for sale on websites like www.ebay.co.uk. It is just a matter of searching for items and subjects that interest you. Whittling down your search with phrases such as ‘travel’, ‘military’, ‘WW2’ or ‘naval’ can help you pinpoint the gems out there.

If you’re inspired by military memorabilia, look out for war diaries, regimental descriptions, letters from remote outposts or descriptive love notes written from the trenches.

Is it a topographical area that interests you? Do you want to find out more about the town or village where your ancestors grew up? Target your searches to that region.

Is there a specific occupation that you would like to find out more about? Unusual trades with illustrated letterheads can shed light on business dealings and prices charged for services offered. From the simple transactions of a rural grocer to the commerce of traders in exotic locations, documents still exist with vivid explanations of everyday life in another era.

Are you drawn towards social history, with a fascination for life in a particular century, the clothes worn and the daily routines carried out? Observations have been penned on every subject, it is just a matter of seeking them out.

Book fairs, attic sales and antique fairs are great places to begin your quest. Don’t forget to rummage through boxes of junk at car-boot sales for those long-forgotten treasures and search the sites of specialist ephemera dealers to see what kind of items are on offer. Remember that each example is unique, so consider that factor when setting yourself a budget.

Some of the most absorbing diaries have been transcribed and are now readable online.

Step back in time and follow the everyday exploits of Samuel Pepys at www.pepysdiary.com. Awash with famous names of the day, it also gives us a window into life in seventeeth-century London.

If your ancestor emigrated to America, it may be worth visiting www.aisling.net/journaling/old-diaries-online.htm. Here you will find details of the exploits of an American midwife, the poignant memories of a Virginian slave, tales of Nebraskan pioneers and the journal of a woman who spent six weeks with the Sioux Indians. Hopes, dreams, fears and excitement from the pens of ordinary men and women who have led extraordinary lives, help to give us a completely different perspective on the times when our own ancestors lived.

Diaries can often hold more than just handwritten entries. Tickets, photographs, newspaper cuttings and other ephemera may be pasted inside.

Examples of diary ephemera.

For those with forebears living in rural Wales in the mid-eighteenth century, some of the pages of William Bulkeley’s diary are relevant and are gradually going online: visit Gathering the Jewels at www.gtj.org.uk/en/articles/diaries-of-william-bulkeley-llanfechell-anglesey-1734-60. Awarded a £6,500 grant, the University of Wales plans to make 1,000 handwritten pages available on the web. Bulkeley’s journals consist of three volumes and cover everything from vivid accounts of farm life in Anglesey to the marriage of his daughter to a pirate.

Eyewitness accounts may take on any form, from the recollections of those aboard an 1850s whaling ship to those experiencing the effects of the Irish potato famine. Use the website http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com as a basis for your own investigations.

Where documents and diaries mention specific events it is always worth trying to track down these details in local newspapers. You may be lucky and discover even more information if the incident was interesting enough to be reported.

PERFECT PENMANSHIP

Study not only the diaries and correspondence penned by your ancestor, but also the writing implement used, the quality of the paper and even their writing style, punctuation and grammar. This will not only give you clues as to the equipment they could afford, but also to their educational abilities.

Step Back in Time

The term ‘pen’ comes from the Latin word penna, meaning feather, but the origins of these writing devices date back much further. Early man chose to convey messages, make drawings and portray thoughts by using his finger as a writing device, dipped in plant juices as a primitive substitute for ink. As we developed and became civilised, more-effective tools had to be found.

Bone and bronze implements were fashioned to scratch naive images and icons onto stone, but it was the Greeks that created a writing stylus that most resembled the pen we use today. Made of metal, bone or ivory, the stylus enabled the user to make marks on hinged, wax-coated tablets that could be closed to protect the scribe’s work. By 300 BC, the Chinese, as an alternative, chose to paint their messages using brushes made from rat or camel hair.

Overcoming language barriers and the opening of trade between nations required us to achieve precision and greater detail when communicating. Although the Egyptians had previously used bamboo reeds as writing tools and vessels to carry ink, it was not until after the fall of the Roman Empire that it was discovered that feather quills had greater potential. Goose feathers were most prevalent, while swan feathers, of a premium quality, were scarcer and more expensive. Crow feathers were ideal for making fine lines and doing intricate work. The hollow shaft of a feather quill acted as a reservoir to hold the ink, which flowed by capillary action to the end of the shaft, split to create a nib for writing. Popular during medieval times to write on parchment and paper to achieve a neat, controlled script, a skilled scribe could achieve numerous calligraphic effects with a well-shaped quill. But there was one drawback: each short quill would regularly need re-trimming in order to produce a sharp nib, so a constant supply of new feathers was always needed.

To overcome this problem, a tool was called for that could carry its own ink supply, was reliable and didn’t require reshaping. The first steps were taken in the nineteenth century when steel nibs were produced by stamping, shaping and slitting a piece of sheet metal. These were then fitted into a holder and dipped into an inkwell to replenish the ink on the nib after every line of writing. Dickens, Austen, the Brontë sisters and their contemporaries would have all used this method to pen their novels. The holders were made from a variety of materials, including gold, silver, tortoiseshell and wood, teamed with equally elaborately decorated inkwells produced for home use, to be displayed on a desk, or as part of a travelling writing set.

Pen nibs and a pottery inkwell that would have slotted into a hole on a school desk. (Stewart Coxon)

Gradually, these advances inspired inventors to come up with a method that eliminated the constant need for dipping the nib into an inkwell.

The Fountain Pen

One of the most notable developments of late nineteenth-century writing equipment was the patenting of the reservoir fountain pen. A ‘silver pen to carry ink in’ was mentioned in the seventeenth century in the diaries of Samuel Pepys, but it was not until 200 years later when pens had their own reservoirs of ink that they became popular and manufacturers such as Parker, Sheaffer and Moseley brought these stylish items to the masses. They were known as ‘fountain’ pens in recognition of the way the ink flowed through the pen and onto the paper; a system of narrow tubes called the ‘feed’ carried the ink from the pen’s reservoir to a gold or steel nib. Perfecting this smooth flow, without the addition of blots or irregularities, initially proved a difficult task.

By 1883 a breakthrough was made. Lewis E. Waterman, an insurance salesman, created a pen that was capable of delivering ink efficiently with his innovative ‘three-channel feed’ device, which allowed air to balance the pressure inside and outside the ink reservoir and stabilise the flow. The Waterman Ideal was filled using an eyedropper mechanism that sucked the ink into the pen to provide the supply. Despite leakages and teething problems with poorly fitting caps and wear to the barrel section, the pens became greatly admired by the general public.

Walter Sheaffer introduced a lever filling method where the lever fitted flush with the barrel of the pen when not in use. The Parker Pen Company patented the button-filler method as an alternative to the eyedropper system in 1913. By pressing an external button connected to the internal pressure plate, the ink sac was flattened to allow the pen to be refilled.

A variety of ink pens and bone rulers. What implements might your ancestors have used for their correspondence? (Stewart Coxon)

Fountain pens gradually replaced their dip-pen predecessors, allowing the user to write more quickly and with less ink spillage. The body of the pen was the perfect base for a wide variety of elaborate decoration and materials to be used. Propelling pencils also proved very popular, with their casings providing an opportunity for decoration and the option to refill them with replacement leads. (Stewart Coxon)

Top Tip

If a desk drawer or box of keepsakes has presented you with a fountain pen, take the time to have a closer look at this engineering work of art. Something as simple as excessive wear to the outer barrel can tell us that this example was not only well used – probably on a daily basis in a world without computers – but also well loved.

Alongside their uses as functional objects, pens were also the perfect vehicle for decoration. Gilding, enamelling, lacquer and metal filigree work can all help to make them extremely desirable. Perhaps your discovery has prompted you to consider buying additional fountain pens. Look out for examples made before 1945 by the following manufacturers: Parker, Mabie Todd (Swan), Waterman, Montblanc, Sheaffer, Wahl Eversharp.

Condition should be your top priority:

• Avoid pens with replacement parts that have been ‘made to fit’.

• Avoid damage where possible, it can be expensive to repair.

• Always buy a pen that you have seen in working order.

• Ensure that the clip on the cap is not broken.

• Check that the barrel and the cap match and whether the cap is of ‘screw-on’ or ‘push-on’ design and that it fits flush to the barrel.

• Ensure that the rubber sac or piston enables the pen to be filled with ink. If this is damaged repair can be difficult. Also check for shrinkage, distorted barrels or a generally poor working mechanism.

• Finally, examine the whole pen for cracks, discoloration and chips to the decoration.

Did You Know?

In 1980, the Writing Equipment Society was formed by a group of enthusiasts who all patronised ‘His Nibs’, a fascinating shop belonging to Philip Poole in Drury Lane, London. Devoting its interests to anything ‘writerly’ and its associated materials, the society has an international membership of over 500 followers.

Among the inkwells and seals, pen nibs and paper knives, you are guaranteed to find a like-minded member with a passion for, and considerable knowledge of, the history of these items. Members receive a journal covering the latest news, articles and advertisements as well as dates of forthcoming meetings and swap sessions. If this is an area of memorabilia that interests you, why not consider joining to find out more? Visit the website at www.wesonline.org.uk/index.html and take advantage of the help, guidance and links to related societies and shows.

From quill cutters to propelling pencils, along with their writing styles, the tools used by our ancestors for their correspondence can help to whittle down the time frame of those dateless examples that you may come across, possibly even helping you to match a letter with a particular individual.

Remember

These clues have literally been left in black and white. Use your imagination and logical thinking to follow them wherever they may take you.

ENCYCLOPAEDIC ALMANACS

Walk into any bookshop today and you’re guaranteed to find a myriad of guides, self-help books, handbooks and manuals on just about any subject, but step back in time and the almanac was the publication you turned to, to find out important information of the day. The early Victorian era saw farming as one of the greatest employers and for those involved in this occupation, an almanac was often at hand on their bookshelves. Almanacs are published annually and contain a calendar for a given year.

Originally essential reading for farmers, almanacs listed planting dates and suggestions for the arrangements of their fields according to the calendar. They also included surprisingly accurate weather forecasts, which predicted rainfall, storms or seasonal highlights that could affect a harvest. They contained astrological information, such as the rising and setting of the sun and moon, details of forthcoming eclipses and tide tables: essential knowledge for fishermen. Like today’s diary, there would be a section of ‘useful information’ listing the dates of important Church festivals and saints’ days. The most common denominator about whatever details were included was that they dealt with the passage of time.

Roger Bacon, an English philosopher and Franciscan friar, is thought to have been the first person to use the term ‘almanac’ in 1267 in the context of astronomy calendars. Almanacs in various forms have been in use for hundreds of years and were produced by numerous countries. At the height of their popularity in the seventeenth century they were second only in sales to the Bible.

British publications include:

Old Moore’s Almanack Written by Francis Moore, the self-taught physician and astrologer of the court of Charles II, this astrological almanac was first published in 1697 and contained weather forecasts. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries this pocket guide was a bestseller and is still in publication today.

Old Moore’s Almanac An Irish publication in print since 1764 and originally written and produced by Theophilus Moore.

Whitaker’s Almanack Published from 1868, Whitaker’s covers a huge range of topics from peerage to politics, education to the environment. When the company headquarters were destroyed in the Blitz during the Second World War, Winston Churchill took a personal interest in ensuring that publication continued. Such was the book’s popularity that in 1878, on erection of Cleopatra’s Needle on the banks of London’s River Thames, a time capsule was placed in the obelisk’s pedestal and an almanac from that year was chosen as one of the items to be placed inside.

Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack Founded in 1864 by John Wisden. During the Victorian era, the purchasing of a Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack was essential for someone with a keen interest in the sport, educating them further on the game and allowing the owner to make their own observations. Growing from 112 pages to currently in excess of 1,500, the 75th edition produced in 1938 was marked with a change to a bright yellow cover, making it instantly recognisable in the years that followed. Previously, the covers had been buff, a lighter yellow or salmon pink. (For more information, see Chapter 15.)

Almanacs produced around a specific subject and kept by your ancestor may provide clues to hobbies, beliefs or occupations of which you had not been aware. Perhaps your ancestor chose to make a life overseas, settling in America to raise a family and work the land; if so you could seek out the American versions, which proved to be just as popular. The first official Farmers’ Almanac was published in 1792 in New England. At this time it was common for astrologers to record their findings and sell them to interested readers, but Robert B. Thomas, editor of the publication, discovered more accurate formulas to create his recordings and weather predictions, which he presented in an entertaining and engaging manner ensuring that his almanac was an instant success.

By 1848 a new editor, John H. Jenks, had appeared on the scene and renamed the publication The Old Farmer’s Almanac, a title that has remained to this day.

As the years passed, additional topics were covered in these much-admired pocket encyclopaedias, from changing transport methods and geographic tables to health and medical procedures such as how to let blood. Their advice and advertisements helped to spread knowledge and educate, while their illuminating passages were even read to soldiers in order to boost their morale. Whether you’ve inherited one of these historical gems or are interested in learning more about a particular period by purchasing your own vintage copy, then an almanac, complete with entries by the user, can give a real insight, not only into agricultural trials and tribulations but also into daily life. A census return may list the occupation of your ancestor as a ‘farmer of 60 acres’, but the additional information provided by an almanac about his farming methods and household accounts would be priceless.

Most useful to the family historian are the almanacs that concentrate on one particular locality, enabling us to visualise the area and the businesses established there. There were occasions when these books served a dual role as both almanac and local directory, combining the information that would often simply overlap in the individual publications. Remember to look out for almanacs that specialised in a particular subject, such as nautical and mining almanacs which are perfect for those of us with ancestors who were involved in these occupations.

What Next?

Specialised British almanacs include The Astronomical Almanac, published by Her Majesty’s Nautical Almanac Office, which contains details of solar systems, positions of the sun and moon, times of sunrise and sunset, eclipses and astronomical reference data. The first edition of the British Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris, published in 1766, contained information for the year 1767, enabling the reader to successfully calculate lunar distances in order to establish longitude at sea.

If you’re not lucky enough to own a family edition, you could try to build a collection of almanacs around a specific area of interest and time frame. Only buy issues with entries that can aid your research and give a feel for a particular period. The seller should be able to enlighten you as to the general coverage of the text before you buy. If you’re trying to find out more about farming life in America during the 1880s, track down examples on auction sites such as www.ebay.co.uk where items regularly come up for sale. Look out for those with references to the machinery used, the daily farming routines and perhaps with lists of household accounts to enable you to work out the expenses faced by someone in this occupation.

Remember

Don’t be fooled into thinking that just because the entries do not apply directly to your ancestors that they are of no use to you. These forms of primary sources give a personal view of what ‘real life’ was like. Your mission is to expand your own family history knowledge through alternative avenues of research. An aspect covered in a diary or almanac could spur you on to find out how this particular incident, event, method or gadget had an impact on the life of your forebear.

CREATING A PRESENT OF THE PAST FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

The thrill of finding your forebear’s hopes and fears written in their own hand cannot be beaten and the information you can glean from the pages is irreplaceable. So with that in mind, why don’t you consider writing your own diary, which will be just as invaluable to your descendants and extended family in the future?

The internet and the speed of email is a tool we cannot live without but the generic, typewritten messages are often impersonal and don’t really give any clues as to the personality of the writer. Yes, in the future it will be possible to print out your electronic thoughts on reams of A4 paper in times roman script but yours will look just like everybody else’s. What better way to preserve your memories than to write them by hand in a diary, perhaps decorated to depict your own style, with doodles, random thoughts, additional ephemera and even the odd crossing out.

In years to come your descendants will have much more fun and excitement in discovering that perhaps you were a really artistic individual, a deep thinker, a comic or a dreamer? They will devour your handwriting for clues to your personality just as you are doing now, but with a little hindsight you can provide a greater insight into your life at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

What you include is entirely up to you, but it is worth giving it a little thought before you start. Think about the information that most excites you as a family historian. Names, dates and places are a must. Will you have a theme, perhaps recording your thoughts on various subjects close to your heart, detailing your occupation and what is involved, or a general diary on day-to-day events concerning you and your family? If you feel that you don’t have the time to commit to daily jottings, compile a weekly log or sporadic journals to record holidays and travel.

Make things easier for your successors by adding details that they can follow up in years to come to find out more about you. Insert your passport number in a travel journal to enable them to research further your lifetime travels; give details of the latest gadgets of the day and most-used appliances – these could seem quaint and old-fashioned in years to come and fascinate your readers – and always include life-changing occurrences and family milestones. Brief descriptions of notable figures and historical events can provide a deeper understanding of the wider world at the time.

Remember

It may seem obvious, but always include your own name and details somewhere within the pages. It is surprising how many vintage diaries have fascinating accounts of life in another era but cannot be tied to an individual due to a lack of ownership information, resulting in a family’s stories being lost to them forever.

TWO

TRAVEL AND TRANSPORT

I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read on the train.

Oscar Wilde

This chapter follows on from the previous theme of diaries in general to concentrate on the specialist area of travel diaries, journals and related memorabilia.

We can often be mistaken in thinking that it was only in the latter part of the twentieth century that we started travelling the globe in earnest. Yes, there are many occasions when our ancestors were born, married and buried in the same village and never strayed far outside it, but there are thousands of other instances when the lure of adventure saw them journey far and wide.

Travel was not solely for the rich – although the ways in which they made their journeys often differed considerably – and many poorer families ended up far from their original birthplace. The search for a better life, the promise of escaping the conditions they had found themselves in and the motivation to find better housing and jobs to support their families were just some of the contributing factors. This could involve moving within the British Isles, such as during the Industrial Revolution when people moved from the country to the flourishing towns and cities for employment, but could also include movement further afield when the living conditions in these areas prompted them to seek new opportunities overseas. Before planes, trains and automobiles, the ship was the only option for those who wished to venture further from our shores. To understand this migration and the physical reminders these trips may have produced we must travel back through the decades to find out more.