Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

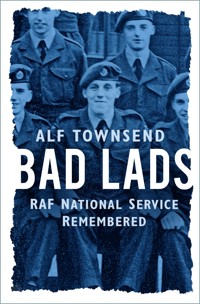

Between 1945 and 1963 over 2 1⁄2 million 18-year-olds were called up for national service. Alf Townsend was one of them, and here he tells his story – the highs and lows of life as a lowly Aircraftman Second Class in the early 1950s. Before national service intervened Alf was 'heading down the criminal road at top speed', having grown up in a North London slum where money was short and local villains were revered. Bad Lads is a warts and all account of Alf Townsend's time in the RAF, when he was transplanted into a completely new world of misfits and officer types, rogues and entertainers, all amusingly described in the author's inimitable style.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 240

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2006

This paperback edition published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Alf Townsend, 2006, 2010, 2023

The right of Alf Townsend to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75247 260 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

This book is dedicated to Nicolette, my lovely wife of almost fifty years. Without her continuing love and support through the terrible days when we lost our eldest daughter Jenny to breast cancer, I wouldn’t have been able to survive – let alone write three books.

We’ve had some tragic times during our long marriage, as well as many wonderful years with our three lovely children and, now, our seven grandchildren. They say a man is nothing without a good woman and I know I am lucky enough to have a truly great lady!

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1 Before the RAF

2 Square-bashing at RAF Hednesford

3 Another Life at Uxbridge

4 Doing My Time at RAF Bassingbourn

5 Homeward Bound

Foreword

Alf Townsend has been associated with the London taxi-trade press for as long as I can remember. He was a founder member of the LTDA (Licensed Taxi-Driver’s Association) more than three decades ago and started writing articles for its publication, Taxi, in the early 1970s. Some years – and many hundreds of articles later – he was invited to join the newly launched Taxi Globe as a feature writer. He moved on to London Taxi Times some years later, then finally the Cab Driver Newspaper.

Alf always writes what he thinks is the truth, and over the years his hard-hitting and down-to-earth comments have often upset many notables in the trade. But many of his regular readers enjoy his fortnightly humorous columns in which he is forever poking fun at the establishment. He has always involved himself in the trade that he loves. For many years he played for Mocatra (motor-cab trade) football team, and later joined the newly formed Golf Society. He has also organised cab-trade golf tournaments, cadging sponsorship from major companies and taking the qualifiers to Spain for a free holiday.

In the early 1990s, Alf was appointed as the senior LTDA trade representative at Heathrow Airport. He helped to form the cab-driver’s co-operative HALT (Heathrow Airport Licensed Taxis) and eventually became its chairman. Alf then started the HALT magazine and, almost unaided, produced and edited it for the first five years or more. The HALT magazine became a popular twenty-page, full-colour front and back publication, which was popular among the cabbies at Heathrow and always showed a small profit.

In the late 1990s, after tragically losing his eldest daughter Jenny to breast cancer, Alf decided to give up all his political positions to concentrate on writing books. Bad Lads is his second book and Alf is hoping that it proves as popular as his first book Cabbie.

Dave AllenEditor, Cab Driver Newspaper

Introduction

Sadly, these are violent times. Street crime is escalating, as are teenage crime and drug abuse. Parents are struggling to keep their kids in check, with little success. It seems as though many young people, not only from the deprived, inner-city areas but also from middle-class suburban families, are totally out of control. At the present time even the police are finding it very difficult to prosecute minors and some of the very worst tearaways, guilty of dozens of petty crimes, are still walking away from our courts having been ordered to pay minimal fines or waste time, in my humble opinion, in useless community service. What must be particularly galling to the police is the attitude of the small, vociferous group of ‘liberals’ who believe passionately that these kids are not responsible for their actions; consequently, the punishments meted out hardly ever match the crimes.

Some experts put this breakdown in family living down to the fact that in some cases both parents are forced to work to support their household, while others consider drugs are the cause. Whatever your age, if you are hooked you’ll do just about anything for a ‘fix’. It seems that unless there is a change in the law in the very near future, or a different attitude to teenage crime is adopted by the courts, kids will continue to run riot and cock a snook at civilised society without any fear of going to prison.

However, many parents have had enough and in the course of my job as an experienced London cabbie – hopefully you’ve read my first book Cabbie – I’ve started hearing more mature passengers harking back to the halcyon days of national service in the 1950s. Older dads are particularly forthright in airing their views, stating categorically that bringing back national service could well solve the escalating problem of teenage crime almost overnight! After more than four decades of driving a taxi, I’m a good listener and, like many other experienced cabbies, I’m adept at tuning in to the feelings of the general public and even the present state of the economy. Did you know that many City high-flyers gauge the economic situation by the number of taxis purchased every quarter? They reckon that if the cabbies are busy and buying new taxis, then the economy must be buoyant and a recession is not on the horizon!

But I digress. This latest interest shown in national service has been highlighted by various reality television shows on the subject. So I thought that it was now the appropriate time to write a book describing the highs and lows of my time as a lowly aircraftman second class in the RAF in the early 1950s. Before national service I’d been heading down the criminal road at top speed. It was about par for the course to do a bit of thieving if you were raised in North London, or anywhere else in London come to that!

The downhill spiral started with petty thieving in ‘Woolies’ in Chapel Market, descended to breaking into deserted and often bombed-out factories and nicking the plate glass to flog to the local shop who made fish-tanks, then lifting the ‘bluey’ (the lead) from roofs and making a nice few quid from the local scrapyard. Moving quickly up the crime ladder, I became a part-time ‘doggie’, a look-out, for an illegal street bookmaker, mixing with hardened criminals who had done time on ‘The Moor’ (Dartmoor) and in ‘The Ville’ (Pentonville Prison). These hard men, with their stories of ‘blagging’ and ‘shooters’, made a big impression on a youngster like me. I liked their flash, expensive suits and the way they pulled a wad of ‘readies’ out of their pockets to have a bet on the gee-gees. I listened to them talking about the guv’nors of the London crime scene. They spoke in reverent tones about Billy Hill, Jack Spot, Albert Dimes and the Maltese gangs that ran the Mayfair brothels. Yet even these tough and brutal gang-leaders had eventually to make way for a bunch of cold-eyed killers from South London. Nobody, but nobody, messed with the Richardson gang, with big Freddie Foreman and ‘Mad’ Frankie Fraser. If you did, then you could well find yourself in a concrete coffin in the English Channel or part of the foundations of the new M4 motorway!

Slowly but surely I began to model myself on these local villains. I got nicked a few times for petty thieving and was sent away for a ‘holiday’. The villains just laughed, especially when I returned. ‘That’s nuffink kiddo; wait until you do some hard-time’, they used to say jokingly. But there were a couple of major things that prevented me from going further down the criminal road. First was my passion for football and the fact that I had been invited to join a professional club as an apprentice pro. However, with the benefit of hindsight, doing my national service in the RAF really made a man out of me. I went in reluctantly as a mere slip of a boy, concerned only about myself and what was in it for me, and always on the look-out for an illegal ‘fiddle’. Yet, in a matter of about only six weeks this yobbo from up the ‘Cally’ (Caledonian Road) had been moulded into a conscientious human being who pulled his full weight for the rest of his hut. Far be it for me to say that reintroducing national service would cure all of the problems among today’s teenagers in one fell swoop. But I know, in my heart of hearts, that without national service I would now be doing ‘hard-time’ in a Category A nick like many of my old mates – some of whom spent half of their lives behind bars.

This is my story of RAF national service in the 1950s and maybe the catalyst for some of the other 3 million or so young men who were made to do their time. After a period of half a century or more, some of the facts have dimmed in my mind. That’s when I have resorted to artistic licence and embellishment in an effort to keep the story interesting. The places and the characters are real and only the names have been changed to avoid any embarrassment – or any possible libel charges or a thick ear! Many people, including me, thoroughly enjoyed Leslie Thomas’s great book of the 1960s, The Virgin Soldiers – I suppose this is a bit like The Virgin Airmen!

RAF swimming certificate awarded to the author in 1953. (Author’s collection)

Chapter One

Before the RAF

The year was 1952. The old King had just passed away and his eldest daughter Elizabeth had been hastily recalled from her tour of Kenya to take up the mantle of sovereign of the United Kingdom and what remained of the old British Empire.

I had been back in London for some seven years since the end of the Second World War, following my bitter and sometimes brutal stay in Cornwall as an evacuee in the care of some wicked people purely in it for the money. Strangely enough, despite my traumatic experiences and apart from ongoing and horrific nightmares, I had grown up a happy and quite intelligent teenager, always looking for a good laugh. I had sailed through the old ‘eleven plus’ exam and moved on to grammar school. I was a pretty good footballer, big, strong and raw-boned with decent heading ability and a fierce shot in either foot. I soon became captain of the school team when I was selected to play for Islington Schoolboys and South of England Schoolboys.

I recall one match in particular against Edmonton Schoolboys. Their captain and star was a tiny little chap called Johnny Haynes, who, as most people remember, eventually became captain of Fulham and England. He was the very first footballer to be paid a massive £100 a week in wages! Their other star was their left-winger Trevor Chamberlain, known to all the boys as ‘Tosh’. Now, Tosh was one of those very early developers; in fact, he was a man in all parts while we were still boys. He had massive shoulders, a deep-barrelled, hairy chest and his legs were like solid tree trunks. And couldn’t he whack a football with his trusty left peg? Tosh must have been the hardest dead-ball kicker of his era. He rose through the international ranks of schoolboy football with Johnny Haynes, and like Johnny he played for Fulham for many seasons. Yet, he never possessed Johnny’s natural skills, and the classier defenders soon tumbled that Tosh was only one-footed. So they forced him out to the touchline and he could hardly ever exploit his explosive shooting with that famous left peg. Nevertheless, Tosh was one of the best young footballers I’ve ever seen. Incidentally, as I recall, we lost 8–0 to Edmonton Schoolboys on that fateful day – and I believe the ‘little fella’ scored a hat trick!

It seems strange that with a background of being dragged up in a North London slum, and apparently only happy when I was kicking a ball around, I had a love of anything remotely to do with writing, which was nurtured by my lovely old English teacher. He was forever telling me that I had a talent for writing and that I needed to move on to university to improve my literary knowledge. But these were very hard times in post-war London. My old Mum was struggling to feed her growing youngsters, hindered by a work-shy husband who was at his happiest when visiting most of the pubs up the Caledonian Road. As the eldest son, my wages were desperately needed to help the family budget. So I left school before the final exams, just to help to put food on the table for our family. I certainly wasn’t unique in this situation: many of my school friends at the time were far more talented than me, but likewise their poverty stricken parents urgently required them to help keep the family in food. I must confess that I often imagine what might have been if only I had gone on to university. But for the most part I’ve been more than happy and contented with my life, with my lovely wife, my kids and now my grandchildren.

So, I had left school and now I badly needed a job. My old Mum’s three surviving brothers, since one had been killed in the Desert Campaign against Rommel in the Second World War, all worked down the old Covent Garden Market as porters. I bashed their ears every time I visited them, and they eventually found me a job in the market. It wasn’t much, but it was paid work nonetheless, and I took home a few quid every week – plus my daily bag of fruit and veg. This item was known to all the market workers as a ‘cochell’, but where the name comes from I do not know. It was one of those customs that probably dates back to the Victorian era, and even the ‘Beadles’, the market police, didn’t dare stop one of the market workers with his cochell. They had probably been forewarned by the bosses, who knew they’d have a strike on their hands if they attempted to stop this ageless perk! Sadly, the old Covent Garden Market, full of colourful characters and customs, was moved to a sterile and clinical, custom-built site at Nine Elms in the late 1970s. The ‘new’ Covent Garden is now a pedestrianised area, a Mecca for tourists with its many boutiques, posh wine bars and restaurants.

By this time I was playing soccer for three different teams every weekend, plus the market team mid-week, with most of the players being years older than me. Then, out of the blue, there came a positive move forward in my blossoming football career. A scout had seen me playing over at Hackney Marshes and informed the guy who ran Leyton Orient Juniors that he wanted me to come down for a trial in Chertsey, Surrey. I was most impressed with the greeting I received when I exited the station. The man in charge met me in an old vintage ‘Roller’ and took me for lunch to a very posh gaff. His name was Mr Loftus-Tottenham, known to all the players as ‘Tott’, and he owned the firm ‘Chase of Chertsey’, which made greenhouses, cloches and the like, and was the official name for the Leyton Orient Juniors at that time. Tott was quite old; well, he looked old to me. He was very tall, had grey hair and horn-rimmed specs and was well dressed. He spoke with an impeccable public-school accent. However, in essence he was an out and out football nut, who spent bundles of his own money in supplying Leyton Orient FC with promising young apprentice footballers.

I soon learned that Tott’s one burning ambition was to discover a future English international star. I recall that his star protégé at the time of my arrival on the scene was a guy called Derek Healey. Now, this guy was red hot and could do almost anything with a football during our training sessions. He would head the ball forever, then he’d juggle it on either knee and cushion it on his neck for a very spectacular finale. Tott was convinced that he’d finally found his future England international. Sadly, Derek didn’t make it as a professional. Like many talented ball players before him, he had the shit kicked out of him by the wily oldtimers and quickly disappeared into obscurity. In fact, out of all the talented squad in the Chase of Chertsey team at that time, only one made the grade in the professional ranks. That was our centre-half Sid Bishop, who went on to play fourteen seasons in the Leyton Orient first team before retiring as a pub landlord. The jump from amateur to professional soccer is really tough and many talented youngsters never make it.

I played centre-forward for Chase of Chertsey for a couple of seasons. We won the league; I scored a lot of goals and got selected for the Surrey Eleven. One day we played another county on the Orient ground at Brisbane Road. We won 4–1; I scored all four goals. After that triumph, my old Dad got a letter from Leyton Orient asking if I would like to join their ground staff as an apprentice professional. I couldn’t wait to mix with the top pros and so I met the manager the following day and signed on the dotted line. All the while I played for Chase of Chertsey, Tott would pull me to one side and tell me that if I worked hard, I could become England’s centre-forward one day in the future. I suppose dear old Tott is long gone now, but he was a lovely man and he gave me a big boost in my otherwise drab, miserable life. My only regret is that I never fulfilled his dream of my becoming an England international. Maybe it was the interruption of my career by national service, maybe it was a lack of effort on my part. Most probably it was because I never really had the God-given talent of someone like the inimitable Johnny Haynes. True, I could score plenty of goals against amateur players. But when I was matched against seasoned pros, they really gave me a lesson in dirty tricks and gamesmanship. I was just a boy playing for fun, coming up against grown men who played serious football for a living to feed and clothe their kids!

Sadly, I never made it to the top of the football ladder. I finished up earning a few quid a game as a part-time pro in the Southern League. Nevertheless, I thoroughly enjoyed my time on the ground staff at Leyton Orient and the buzz of finally being selected for their reserve team was electric. The fact that my début was against Millwall and that I was kicked from one end of the field to the other didn’t seem to matter. I thought I was on my way to the top, so a few bruises were nothing! In retrospect, I’m happy that I was given the opportunity by the then manager of Leyton Orient, dear old Alec Stock, a lovely man. I mixed with guys who were household names at the time and was given my prized possession, my players’ pass, which allowed me to sit on the touchline at any ground and at any league game. I could even stroll into the mighty Arsenal’s ground and watch the top stars in action! I relished my short career as a minor celeb, as did my old Dad. He got many a free pint out of it whenever I got a write-up in the sports pages! His favourite ploy was to gather a bundle of the relevant newspapers and make a visit to most of the pubs up the Caledonian Road. His spiel was always the same: ‘Did you read this in the paper about my son?’, he would enquire of one of the guys at the bar. This invariably led to a free drink, or two or three! Nobody can ever take those memories away from me. So why am I prattling on about my early football ability, you may well be asking? Well, later on during my RAF national service this ability became the catalyst for many different happenings and so forms an integral part of my story.

Looking for a Way Out

Most of our Caledonian Road gang were about the same age, and all of us knew that national service was just around the corner. We used to sit for hours on street corners nervously talking about how we could wriggle out of it. Digressing slightly, I recall one day when we were all sitting on a wall at the top of our street and I noticed a group of girls gathering near a block of flats opposite. Being dead nosy and hoping to chat them up, we crossed the road to join them. It turned out that they were all members of the Johnny Ray Fan Club. Now, in the early 1950s, Johnny Ray, an American pop-singer, was the biggest thing to hit the UK since sliced bread! He was a skinny little bloke with a huge hearing-aid, and I thought his singing was crap. Nevertheless, his records sold in their thousands and he had been invited to come over and sing at the famous London Palladium. The girls told us with bated breath that the famous Johnny Ray was in the block of flats visiting the secretary of his fan club. So they all started screaming, ‘John-nee, John-nee!’, until eventually this little guy appeared on a balcony some six storeys up and started waving and singing his hit single ‘Cry’. All the girls started swooning, while we shouted, ‘You’re crap, you can’t sing to save your life!’ Lovely, lovely memories, especially since dear old Johnny Ray died fairly recently. He really was the very first of the pop idols. Sadly, he finished his distinguished career by singing for peanuts in the bar of a Las Vegas casino.

For sure, we all had plenty of front and cockney chat, but when it came to giving up your life for Queen and Country, then it was a different ball game! The Korean War was looming on the horizon, and the distinct possibility of becoming cannon fodder in some foreign field made us extremely apprehensive. That prospect persuaded me from day one that the Army would never ever get me! We discovered various options that could be used as possible ways out. First was the use of deferments. These were only given to those going on to university or in apprenticeships, or those in important jobs like coal-mining. But even if we all moved up north and took up coal-mining, you still had to do your time when the job or the course had finished. So deferments weren’t an option for our gang. The Merchant Navy didn’t seem a bad choice. But, again, you had to serve the same time as national service, and, who knows, one day your ship might be bound for Korea with a full load of explosives and become a prime target for North Korean fighter planes – or even one of their submarines. Anyway, for somebody like me who could quite easily get seasick on the boating lakes at Finsbury Park or Hyde Park, the Merchant Navy definitely wasn’t a viable alternative! That left going on the run, so the authorities couldn’t trace you, or deliberately injuring yourself so that you would fail the medical. Many of my mates did go on the run when the time came, but they all got rounded up eventually and were still doing time in the ‘Glasshouse’ (the Army prison) long after I had finished my national service.

The only two guys I know of who beat the system were the notorious Kray twins. The Army couldn’t break them despite their many months in a bad-boys’ glasshouse, so they finally ‘surrendered’ and begrudgingly, gave both twins a ‘DD’, a Dishonourable Discharge. And as for deliberately injuring oneself to escape national service, as a fit young sportsman that never appealed to me. But I remember it was of interest to one of our gang. His name was Harry, and for obvious reasons his nickname was ‘Crazy’ Harry. There’s always one nutter in any gang, isn’t there? ‘Crazy’ Harry stated from day one that no way was he ever going to do national service, and he kept his promise. The guys told me that ‘Crazy’ Harry had stuck a pointed object deep into one of his ears and deliberately pierced his eardrum. Okay, so he beat the system. But, unfortunately, he suffered great pain for the rest of his life with mastoiditis and tragically died at an early age.

So, the rest of the gang had fully discussed the options in an effort to beat the system, but to no avail. It seemed inevitable that I, as a super-fit young athlete, would be forced to serve my Queen and Country, whether I liked it or not. I needed to sit down and carefully think about my possible courses of action. The Army was definitely out for me, even though many of my mates up the Cally eventually finished up in the Green Jackets and spent most of their time in Germany. And the only way you could get into the Royal Navy was to sign on for a minimum of nine years. So that was a no-no. That left the RAF, known to all my mates as the ‘Brylcream Boys’. I had heard some gossip from the older lads who had done their time in the Army. They reckoned that whenever they were on manoeuvres in Germany and had to sleep under canvas the RAF detachment lived like lords in the local farmhouses with plenty of food, wine and home comforts. That sounded just my cup of tea, and I stored that rumour in my brain right up to the time of the selection board! I accepted the inevitable and soon before my eighteenth birthday the postman delivered another present, my call-up papers. I had to fill in the details on the form. ‘I would like to join the RAF’, I wrote, adding that I had a grammar-school education. Occupation? What the hell – I put down ‘professional footballer’, which was rather presumptuous to say the least. But it worked. I received another notice a few weeks later to report to the chief medical officer, I think it was in Theobalds Road, Holborn, and I knew that this was the RAF Medical Officer.

I sailed through the medical as A1, a perfect young and healthy specimen of manhood. Even being asked to drop my trousers and ‘bend over and cough’ didn’t bother me one little bit! The postman called again a couple of weeks later, and the letter gave me the news I was hoping for. My carefully laid plans had worked. I had managed to bypass the rigours and hardships of the Army and had been accepted into the RAF. Nobody, but nobody, wanted to do national service. But if it was inevitable, then it made sense to try and get into the service that was probably the cushiest number available.

‘Well then, airman, who’s your four-legged friend?’ (RAF Museum, Hendon)

A Travel Warrant to Padgate

For starters, I didn’t have a clue as to the whereabouts of my destination of Padgate. But I knew it was somewhere up north, because my travel warrant instructed me to get the train from King’s Cross on a given date and time.

The train was packed to the roof with young guys like me from all over the south of England, all in the same situation as me and all a wee bit nervous thinking