9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

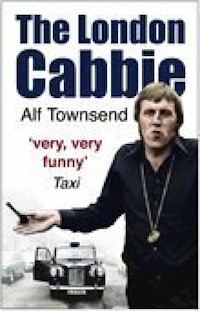

Forty years ago Alf Townsend passed The Knowledge - after 14,000 miles on a moped round central London. Since then he has covered millions of miles in his taxi. This book includes a selection of his extraordinary and hilarious tales of everyday life as a cabbie, in which we meet Mr Whippy and Violent Pete, Bread Roll Mick and the Motorway Mouse, Claude the Bastard and the mysterious Mr X. Alf also examines the history of cab-driving in the capital - including the variety of taxis that have been used - and even tries to shed some light on the most ancient and obscure Hackney Carriage laws that are still on the statute book. (Do you know why a taxi is so tall? So a passenger can get on board wearing a top hat: it's true...) Concluding with a look at the seamy side of night work, the rise and rise of the mini-cab, and what the future may hold for the London cabbie, Alf Townsend's book will be entertaining reading for all Londoners, and anyone else who has travelled in the back of a black cab.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Foreword

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1The Knowledge

2From Horses to Horseless Carriages

3The Butterboy

4Eccentrics and Famous Faces

5The Arrival of Minicabs

6The Heathrow Story

7Farewell to Night Work

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD

Alf Townsend has been associated with the cab trade press for as long as I can remember. He was a founder member of the LTDA (the Licensed Taxi Driver’s Association), and first started writing articles for their publication, Taxi Newspaper, way back in the 1960s. Some years later, he was invited to join the newly launched Taxi Globe. He moved on to the London Taxi Times, then finally the Cab Driver Newspaper.

Alf always writes what he thinks is the truth and over the years his hard-hitting and down-to-earth comments have often upset many notables in the trade. But many of his regular readers enjoy his fortnightly humorous columns, forever cocking a snook at the establishment. He has always involved himself in the trade that he loves. For many years he played for the Mocatra (Motor Cab Trade) football team and later joined the newly formed Golf Society. He organised Cab Trade Golf Tournaments, gaining sponsorship from major companies and taking the qualifiers to Spain for a free golf holiday.

In the early 1990s, Alf was appointed as the senior LTDA Trade Rep. at Heathrow Airport. He helped to form the cab-drivers’ cooperative, HALT (Heathrow Airport Licensed Taxis), and eventually became its Chairman. Alf then started the HALT Magazine and, almost unaided, produced and edited it for the next five years or more. The HALT Magazine became a popular, twenty-page, full-colour publication, which always showed a small profit.

In the late 1990s, Alf decided to give up all his political positions and concentrated instead on writing books. This book is his second effort and the first to be published.

Dave Allen

Editor, Cab Driver Newspaper

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to the loving memory of our wonderful daughter Jenny, who tragically lost her painful, six-year battle against cancer on 27 December 1999. She was just one month past her forty-first birthday when she died. During those dark days, I wouldn’t have been able to carry on without the deep love of my darling wife Nicolette and the support of the rest of our family: Jenny’s caring husband Keith, their lovely son Sam, my son Nick, his wife Rose and their two children Ruben and Soela, and last but not least, the love and affection from my daughter Jo, husband Adam and their children, Charlie, Holly and the twins Albert and Jack. They all helped me to write this book.

‘Your spirit is our strength, darling.’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to my friend and colleague Philip Warren, a well-known cab trade historian, for allowing me to quote extensively from his book The History of the London Cab Trade, from 1600 to the Present Day. Without his kind permission I wouldn’t have been able to construct my chapter, ‘From Horses to Horseless Carriages’. Also, a big thank-you to Philip for supplying me with many of the old photos from his extensive collection. Philip’s book is well worth reading – especially if you are a history buff! My thanks also to Stuart Pessock, the editor of Taxi Newspaper, for letting me raid his photo collection and to my son Nick for taking the photos of Heathrow, the Knowledge Boys and the Cab Shelters. Thanks also to Malcolm Linskey, the ‘boss-man’ at the Knowledge Point School for the pics of the Knowledge Girls.

INTRODUCTION

It’s been more than three decades since a book has been written about the famous London cabbie, so I thought it was time to write another. To be perfectly honest, my dear wife has been nagging me for a long time to get on with it! That first book, written by the late Maurice Levinson – my very first editor when I became a trade journalist at ‘thirty bob’ per edition, was very popular at the time and climbed to Book of the Month in the Evening Standard Book Awards.

The London taxi trade and the London cabbies are steeped in a long and interesting history. Oliver Cromwell first gave us our charter more than three hundred years ago and Parliament has renewed it without a break over that long period of time. In this book, I will attempt to explain some of the ancient Hackney Carriage Laws that are still on the statute book and try to interpret some of the many vagaries attached to the Conditions of Fitness laid down by the Public Carriage Office (our controlling body) for every licensed taxi in London.

When I did the infamous ‘Knowledge of London’ over forty years ago, it involved a fourteen thousand-mile slog on a moped around the streets of London, for God knows how many months. Then, having to answer oral questions on a monthly basis about thousands of streets, hundreds of clubs, theatres, hospitals, etc. to a not-very-nice examiner, before being considered proficient enough to earn the coveted green badge. The class of ’61 had to answer those diabolical questions at the old Public Carriage Office in Lambeth Road, which closed in the mid-sixties. The new Public Carriage Office in Penton Street, near the Angel, Islington, introduced some basics such as an appointment system, where the ‘Knowledge Boys’ were actually given a card with the time and date of their next appointment written on it. This was clearly a major step forward for the nervous youngsters and one we would have dearly welcomed at Lambeth Road. But I can only write about my own experiences; and even streetwise cabbies who have been on the road since the late sixties may find my hair-raising stories about Lambeth Road quite entertaining.

Many of the funny – and sometimes naughty – stories told in this book are from my many friends and acquaintances in the trade, and I devote a whole chapter to the ‘girls on the game’, the call-girls and the Soho villains. This is not an attempt to titillate my readers. This was London life in the early sixties before the law banning prostitution started taking effect. I also spend a lot of time talking about those weird and wonderful characters who were regular cab ‘riders’ in those far off days.

London cabbies make up a wide cross-section of society. They come in all shapes and sizes and all colours and, since the Sex Discrimination Act was introduced, they now come in the female form too. We have in our midst ex-professors, former senior police officers, teachers, ex-professional footballers and boxers and a wide range of other callings. From what I can make out from talking to these different people, they originally did the Knowledge only to subsidise their income. Then they got to like the freedom of the job and went full-time cabbing.

I have thoroughly enjoyed my forty years of being a London cabbie and have been lucky enough to indulge my passion for writing as a hobby. My ugly mug has been staring out of the trade papers at the unfortunate cabbies for over thirty years. I have written literally hundreds of articles over that time and also edited a trade magazine for quite a few years. Everybody in the trade knows me as ‘Alf the Pipe’. So, to all my many friends and acquaintances in the trade, this is an opportunity for your relatives and friends to read about your job and your life; who knows, you might even be in the book! As licensed taxi-drivers we know what’s happening out there on the streets of London. Hopefully, my book will go some way in enabling the ordinary person to appreciate the finest taxi service in the world!

Incidentally, the cabbies’ names used in this book are not their real names; in fact they are a compilation of many cabbies. I just wanted to mention that in case I get a ‘right-hander’!

ONE

THE KNOWLEDGE

BEFORE THE KNOWLEDGE

Just contemplating doing the Knowledge in 1960 was a pretty daunting prospect for someone in my circumstances at that time. I had no job and I was on remand, accused of a serious criminal charge. We had one child with a second on the way. I had no savings to talk about, so I needed to find a suitable job that would give me some spare time to roam the streets of London for a year or more. I already had a HGV (Heavy Goods Vehicle) licence, so I decided to train for a PSV, which would enable me to drive a coach. Back in those days you didn’t get any help or assistance from any of the coach companies; sure, if you held a PSV licence (Passenger Service Vehicle), they would give you a job. But, as for passing the test, you were on your own and had to pay the going rate to hire a coach on the day of your test. With the benefit of hindsight and a huge slice of luck, my choice of date to pass my PSV licence proved to be valuable to me. The little Welsh examiner who passed me for my PSV licence happened to be the very same person who took me on my taxi-driving test a year or so later. I can distinctly remember him saying to me that he knew my face and had I failed the taxi test before? When I told him glibly he had passed me to drive a forty-nine-seater coach a year or so ago, I knew I was home and dry. The failure rate on the taxi-driving test, or ‘The Drive’ as the boys called it, was quite high. Word had it that some of the examiners took great delight in ‘holding back’ the Knowledge Boys for one last time before they finally got their coveted green badge. But I knew I was different. The little Welsh examiner couldn’t possibly fail my driving on a four-seater taxi when he had already passed me to drive a forty-nine-seater coach! He knew it and he knew that I knew it. When we eventually got back to Lambeth Road in the taxi, the little Welsh examiner – almost grudgingly – told me I had passed my test. But I was very heavy on the clutch – just like a coach driver!

Plan A had succeeded: I had my PSV licence; now I needed a job. Grey-Green Coaches of Stamford Hill was my next stop and I was taken on. The new drivers always got the dodgy jobs where there was no ‘beer money’, like the school run, the service routes and the changeovers. The changeovers consisted of driving the coach on a service run, stopping at all the stops as far as Brentwood, in Essex. Then on to Colchester, where you would change over with a driver who had come from Great Yarmouth. He would go back whence he came with your coach and you would do the same, with no ‘beer money’. I realised much later, when I was a lot wiser, that it was all about ‘bunging’ the foreman who gave out the work. The same drivers always seemed to get the cream jobs, like the pub outings and trips to the races with the Licensed Victuallers. A coach driver in those days could more than double his weekly wage in tips with trips like these. I really enjoyed the pub outings and the factory outings to dear old Southend. Again, it was a learning curve in life. When you took a crowd of women from a factory in the East End, you needed to be on your best behaviour. They were all out for a good time, but there was a moral limit to their larking about. And if you took a liberty, as in the case of a fellow young driver, you could find yourself minus your trousers and tarred and feathered in the nether regions to boot! I used to give a song in the local pubs at that time, so I was always popular with the ladies and got good ‘beer money’.

There was one particular job that nobody wanted to do, so it was given out as a punishment and that eventually meant me. I had left behind a young, unaccompanied mental patient at Colchester coach station. Nobody had told me about this young girl, but the management passed the buck to me. So, I was given the dreaded ‘Ghost-Train Run’ as my punishment. The Ghost-Train was the very last coach to leave Kings Cross at night, I think it was 10 o’clock. It swept up all the late travellers at every stop as far as Colchester. Then on to Felixstowe and back to Ipswich Garage, which we shared with the Ipswich taxi-drivers. A few hours’ kip on the back seat with a blanket, a wake-up call and a cup of tea from the cabbies and it was back heading home to London at 1 minute to 6.

Strangely enough, this job that nobody wanted suited me fine as a potential Knowledge Boy. I could do my runs on my moped for the rest of the morning and early afternoon, then go home and have a sleep before doing the Ghost-Train at night. So, much to the surprise of my fellow drivers, I offered to do the Ghost-Train on a regular basis!

SIGNING ON

In those far-off bureaucratic days, even trying to sign up to do the Knowledge was a pain. The applicant had to produce a photo and a full list of convictions, both criminal and civil. I got in their bad books straight away by forgetting to put down a ‘major crime’ I had committed as an evacuee in Cornwall during the war. I had been fined a pound by a Magistrate in Newquay for stealing, or ‘scrumping’, apples.

The situation turned decidedly dodgy, however, when I informed them that I was presently on remand accused of robbery and receiving! The boss of the Public Carriage Office (PCO) called me into his office and told me in no uncertain terms that I could come back if I was found not guilty, but if I was convicted not to bother ever again. Thankfully, the charge was thrown out of court and I went back to my employers to collect three months’ back pay that was owing to me. Then I immediately put in my notice, because I knew I was top of the list for being ‘fitted up’, and applied to the PCO once more. My only claim to fame as a villain was being thrown into a holding cell at Old Street Magistrates Court with the notorious Kray twins, Ronnie and Reggie. I got on all right with the twins because we had mutual friends.

Even as early as the late fifties, the Kray twins had attained a formidable reputation among the London tearaways. Their following swelled, and the Kray myth and the hero-worship began, after they ‘defeated’ the British Army with their total disobedience of National Service rules and regulations. Despite spending most of their service in the ‘glasshouse’ (Army prison), they refused to bow to Army discipline. And, speaking from a little experience, that took some doing, because some of those Redcaps in the nick were tough cookies. The Army finally surrendered and got rid of them by giving them a ‘DD’, a Dishonourable Discharge.

But unless you knew the Krays they didn’t look at all like your average villains. Even in the holding cell they were wearing expensive, matching suits, with the square-cut box jackets that exaggerated their barrel chests. Smart silk shirts, matching ties and expensive black leather shoes completed their attire. I can always remember their hair, thick and black and brushed back without a parting. And their prominent black eyebrows seemed to make their eyes even colder and more intimidating.

Luckily for me, we had a mutual friend, and after I had shown my respect for them with the accepted friendly greeting of ‘You all right, Ron, you all right, Reg?’, I said, ‘I’m a mate of Big Patsy out of the Angel.’ I received a long, hard stare from those cold eyes. Oh my Gawd, I thought, do they think I’m a police plant? Then Reggie said, ‘How’s old Patsy doing, is he all right?’

I nodded my reply and the conversation was over as they moved into the corner to discuss some private business. I didn’t dare ask them why they were banged-up. But I had heard a whisper on the grapevine that they had been charged with assault with a deadly weapon – after they allegedly cut up a geezer with a bayonet! Incidentally, I heard a few days later that the twins had walked free from the alleged bayonet attack. And why? Simple – nobody had the bottle to give evidence against them. And I made them right if they wanted to carry on living!

What always fascinated and intrigued me many years later, after the Krays had built up a criminal empire, was why they got involved personally with the murder and violence that got them locked away for the rest of their lives? They had many underlings to do their dirty work. So was it simply a macho thing to show all and sundry who was still boss?

As for me, on the day, I was treated like royalty in the holding cell, because the old custody sergeant wrongly believed I was one of the firm. He kept calling me ‘mate’ and asking me if I wanted another cup of tea or a fag and was I all right.

When my name was called to walk up the steps to the dock, I don’t mind telling you I nearly wet myself with fright. Take it from me, it’s one of the scariest – and loneliest – things in life. You suddenly surface from the dark depths of the cell area, into the bright lights of the courtroom and a hubbub of noise. And there, looking down on me, was this skeletal face wearing those funny specs with half-frames. This was the ‘Beak’, or Magistrate, and sitting next to him was a rather large lady with freshly-permed hair and big, muscular arms. I remember thinking at the time – I always think funny things when I’m stressed – that she would be better suited with a whistle in her mouth and blowing it for the bully-off in a ‘gels’ hockey match!

I had been well versed by my legal team and I stuck to my story religiously, trying all the time to look innocent, even though with my muscular frame and broken nose, I looked a bigger villain than the Krays! But the turning point of my trial really came when the prosecution called in their star witness. He was a real old carrot-cruncher that they had pulled in from way out in the sticks. You could tell from the off that he was wetting himself more than me – and he wasn’t even on trial! The odds were that he’d never left his Suffolk village before, let alone appeared in a London courtroom. I saw the look of utter despair on the top cop’s face as my barrister tore the old guy to pieces. It appeared that the old guy was in charge of a bonded warehouse. Now, for the uninitiated, a bonded warehouse is only ever opened on clearance by HM Customs, and the prosecution’s entire case rested on the fact that I had been arrested for having stolen property in my house in August. Yet the bonded warehouse holding that property hadn’t been cleared by Customs until the following month. This proved, without a doubt, that the goods had been stolen at my depot, while in transit to the warehouse, by a person or persons unknown. Yet my smart-arsed barrister persuaded this old carrot-cruncher to tell the court that, yes, it could have been possible for someone to have stolen some of the contents of the bonded warehouse and sold them on to me, without his knowledge, of course.

For sure, I was elated when the Beak threw the case out, much to the chagrin of the top cop, who had spent months collecting the evidence. But I had a guilty conscience about the old guy who had been given a roasting for being so naive and honest. And more than four decades down the line, I still feel guilty – especially when they had me bang to rights. So, instead of going down for a long stretch, as the ‘friendly’ top cop had previously told my wife, I walked out into the spring sunshine a free man.

Sadly, many of my good mates at the time got themselves involved in criminal activities and finished up doing time. But not me. I make no bones about it, I had been extremely fortunate to walk away scot-free. But that experience had frightened the living daylights out of me and has been indelibly imprinted in my mind for more than forty years. So, a couple of years down the line, after I had managed to complete the dreaded Knowledge of London and gained the coveted Green Badge, I vowed, for the sake of my wife and kids, that I would never leave the straight and narrow again. I had scrimped and saved and worked like a dog to get that Green Badge and there was no way I was going to lose it by getting involved in shady deals, or buying ‘bent’ gear. And, touch wood, all these years later I’ve kept to my promise. Mind you, I’m not quite as straight as your Roman roads!

THE INTERVIEW

My record had been checked, I had no County Court summonses pending, the photo really was of me, so it was interview time for the Knowledge. All the new boys were ushered into a bare room at Lambeth Road, a crumbling Edwardian edifice that seemed more like a prison. We waited in awe for the Chief Examiner. In those far-off days, all the staff and examiners were ex-policemen, so immediately, they didn’t like taxi-drivers or even potential taxi-drivers. Their attitude could best be termed as disdainful, or at worst, totally bored and unhelpful. After many months on the course, I realised that their rudeness and disdain were a deliberate ploy to make you lose your temper, a bit like the drill sergeant in the Army. Once they got you wound up and you blew your top, that was the end. You were no longer deemed to be ‘a fit and proper person to become a licensed taxi-driver’ and you were thrown off the course – permanently. The Chief Examiner entered the room surrounded by his assistants, almost like royalty as I recall. He was a wiry little guy in a smart suit and his grey-flecked hair was swept back tight on his head and plastered down with Brylcreem. He sported a neatly-clipped Hitler-type moustache. But the thing that impressed me the most was his ramrod-straight back. It was so straight and rigid, almost as though he was wearing a corset! He moved in a whippet-like way and his eyes were looking all over the class. With my recent unpleasant experience of National Service, I immediately said under my breath, ‘This guy’s just gotta be ex-military, probably a long-serving Colour Sergeant or even a Regimental Sergeant Major.’ Yes, I could well see him on the parade ground, patiently measuring out the paces with his stick!

He stopped at the top table and his minions lined up either side of him, whilst we all looked on nervously. He was obviously enjoying every minute of being the focal point, almost like reliving his military past and giving a briefing to the SAS or a crack commando unit before a daring raid. I remember thinking to myself at the time, this guy likes the sound of his own voice and I’ll lay a hundred pounds to a penny, that he calls us ‘laddie’. And I was spot on! He cast a beady eye around the room attempting to get some eye contact. ‘Has anyone tried this before?’ he asked in a thin, reedy voice. Everyone looked round when a couple of the guys put their hands up rather timidly. ‘Well I never,’ he chuckled, ‘I reckon you two blokes must be barking mad.’ His assistants started chuckling, so I started chuckling, just a little too heartily. He fixed his beady eyes on me and, walking across, he shouted, ‘It’s not that funny, laddie, because doing the Knowledge just once can drive you mad. So, if these two gents are starting it for the second time, they must be barking mad.’

Right, I thought to myself, it’s just like National Service and the drill sergeants. Keep your head down and don’t get noticed. After the initial jokey start, it was down to business and the distribution of the ‘Blue Book’, containing over four hundred runs or routes that criss-crossed all over London. Up piped the reedy voice again. Holding a white pamphlet up in his outstretched hand, he said theatrically, ‘This white pamphlet that I am a-holding up for all of you to peruse is called, believe it or not, the “Blue Book”. Some of you may be thinking, why is it called the “Blue Book” when it’s white?’ Then chuckling to himself at his own clever humour, he continued: ‘You may think that I am so clever I will know the answer. But I don’t. It was called that by taxi-drivers many years ago and nobody knows why.’

Again, a ripple of laughter from his audience while he stood beaming, holding his thumbs in his waistcoat. ‘This “Blue Book” is your Bible,’ he went on. ‘You need to learn every single run by heart. And you need to be able to recite each and every one of the four hundred runs and be able to see all the streets in your head.’ He paused to make sure there was fear in all of our eyes, then he continued in full flow, ‘As if that’s not enough, you will need to learn all the many hundreds of points of interest that you pass on every run and be able to spot the run when the starting and finishing points are changed by your examiner during your monthly tests.’ He grinned to himself, while a murmur of disbelief came from his captive audience. ‘We’re wise to all the tricks up here,’ he went on. ‘If we were only to ask you simple points like Piccadilly or Buckingham Palace, you’d all be sitting at home on your backsides, just map-reading, wouldn’t you, eh?’ He cast a beady eye on his shell-shocked audience, just to make sure his comments had been digested, before going on again: ‘Let me warn you gentlemen,’ he said in a sombre voice, ‘if any of my examiners inform me that they think one of you is sitting on his arse map-reading at home, you’ll be in for the high jump. We caught one joker last week who was calling over a run and he decided to turn right from Holborn Viaduct into Farringdon Street, which is a fifty foot drop to the street below.’

He paused to receive his expected applause, his men were laughing and the joke was obviously an ‘old chestnut’. Many of us didn’t know where the hell Holborn Viaduct was, but we still had to force a laugh – it seemed to be expected. The Chief Examiner started gathering up his papers and looking around the room, almost as though he was looking for a face he didn’t like. I kept my head buried in the Blue Book, looking as studious as possible. ‘Right, gentlemen,’ he said, standing up, ‘the rest is up to you. If you want to become a London taxi-driver, you will need to work very hard at it, day and night.’ He started towards the door followed by his entourage, and with a last theatrical gesture he turned and said, ‘I want you all back here in fifty-six days, bright and early and ready to answer any question about London. Keep at it, lads.’