Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

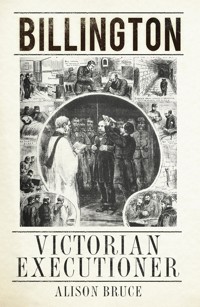

'An insightful and gripping account that will take you into the dark but fascinating world of a Victorian executioner.' – Stewart P. Evans Between 1884 and 1905 James Billington and his three sons, Thomas, William and John, were responsible for 235 executions in Victorian Great Britain and Ireland. They hanged many notorious murderers, but equally fascinating is the story of the family. Did James really feel he served society and justice, or did this position satisfy something more personal? Billington: Victorian Executioner provides a complete account of the stories behind James Billington's executions, as well as the real man behind the rope – a man whose business was death. This enthralling biography is an exciting addition to any true crime bookshelf.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to Manfred Louis Masset24 April 1896 – 27 October 1899

First published 2009

This edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Alison Bruce, 2009, 2023

The right of Alison Bruce to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75247 406 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

One:

‘Thaal Nivver Feel It’

Two:

‘Worse than Helen’

Three:

‘He Never Had a Dream in his Life’

Four:

Into the Mills

Five:

‘Poisoning He Goes’

Six:

‘A Copper Pot’

Seven:

‘Knock, Knock, Knock on the Floor’

Eight:

A Murder Charge Made for Two

Nine:

Boyhood Haunts

Ten:

In a Position of Trust

Eleven:

Scandal Quote

Twelve:

‘Nobody Believes Her’

Thirteen:

Too Many Lies

Fourteen:

‘I Wish I Had Never Come’

Fifteen:

William’s Reign

Sixteen:

The End of the Billingtons

Nigel Preston Interview

Author’s Note

Appendix 1: Execution Ropes

Appendix 2: School for Hangmen

Appendix 3: Index of Executions

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must start by saying a big thank you to Stewart P. Evans, who is always exceedingly generous with his time and expertise. And another big thank you to Matilda Richards and the staff at The History Press for turning my manuscript into such a beautiful book.

My appreciation also goes to a group of people who have all helped me at various stages and in a variety of ways (in alphabetical order): Phillip Atkinson, James Barton, Nick Connell, Glenda Eaves, Rosie Evans, Steve Fielding, Ralph Harrington, Kimberly Jackson, Jo Malton, Carol Noble, Nigel Preston, Richard Reynolds, Matthew Spicer and Laura Watson. And, as always, Natalie, Lana and Dean.

Finally, I wish to thank my inspirational agent, Broo Doherty, for her unwavering support, and Jacen for his steadfast commitment to my books.

In many official documents and newspaper reports there were variations in the spelling of names, for example Wyndham and Window. It has not been uncommon to find two or three different spellings of one name within the same document. Wherever possible I have taken the most official record of the spelling, for example a registration of birth, death or marriage over a newspaper report, or court record in preference to handwritten letters. Sometimes this has meant that I have chosen a spelling that varies from the spelling used in some other books and accounts, but in each case this has occurred after making a decision based on which spelling I feel is most likely to be correct. It is also worth bearing in mind that spelling of names varied within families, for example Whitham and Witham, which indicates how much more emphasis we put on the consistent spelling of names than in Victorian times.

INTRODUCTION

James Billington executed some of Britain’s most notorious killers including the serial killer Dr Cream, and Mrs Dyer, the baby farmer, but I quickly discovered that the little-known cases were equally macabre; like the man who attempted to boil away the body, and the woman who played loudly on the piano to conceal the murder taking place in the upstairs room. For me, this book was not just about the extreme personalities, but the people who were driven to commit their crimes, and, of course, the man whose choice of employment was one of the most disturbing imaginable.

The large number of criminals James Billington executed, 151 in total, meant that there was a great opportunity to look at cases that have not previously received much attention. The research generated a huge volume of information and as I worked through, the gripping story of the executioner and his career emerged.

After researching some of the cases, I chose not to concentrate only on the most famous examples. Gaining the best insight into the challenges Billington faced would only be possible by looking at a representative cross-section of the crimes and by picturing both the people he executed, and the families and communities that confronted him at each appointment.

In addition, there was at least one murder victim in connection with each of these executions, and I did not feel it right to automatically skip over any cases. Homing in on only the cases shrouded in mystery, notoriety or bizarre circumstance gives Victorian crime a kind of dark glamour and an air of fiction. In contrast, showing the long-forgotten killers and the desperate plight of their victims paints a more rounded picture, not only of crime at that time, but of Victorian society as a whole.

Capital punishment is also an emotive subject and it is far easier to justify the use of the death penalty in those extreme cases where the perpetrator can be described as evil, than when the criminal act is more the product of society’s failings than of individual weakness.

Something that has always interested me about executioners is their motivation for applying to the post and the long-term impact this role has on their personal lives and psychological health.

Some of the biographical information has been drawn from family accounts and using rare copies of other executioners’ memoirs, making this a unique account of James Billington and his days as England’s number one hangman.

This has been a fascinating book to research and write, and I think that it provides a huge insight into the issues facing Victorian hangmen and the people who struggled to live in Britain during this era.

From boiling cauldrons to tinkling pianos, it certainly dispels the myth that it was a more moral and law abiding age.

Alison Bruce, 2009

CHAPTER ONE

‘THAAL NIVVER FEEL IT’

James Billington. (Author’s collection)

Joseph Laycock was a hawker who had cut the throats of his wife and four children. He was held at Armley Gaol in Leeds and the date for his execution was set as 26 August 1884. In the minutes before he was hanged, Laycock spoke to the executioner and asked, ‘You will not hurt me?’

Possibly his question was more than just the usual final thoughts of any condemned prisoner, perhaps he was acutely aware that the man with the responsibility of ending his life was not only new to the post of hangman for Yorkshire, but also untested.

‘No, thaal nivver feel it, for thaal be out of existence i’ two minutes,’ Billington replied, and within moments the thirty-seven-year-old Lancastrian had proved that he was more than fit to hold the position.

Becoming a hangman certainly seemed to be a departure from Billington’s full-time job as a barber, but in truth he had only been appointed after showing an almost obsessive keenness for the post, a desire that had begun before he was old enough to work.

James Billington’s father was also called James. He was a Preston man who had married a Bolton girl named Mary Haslam. Initially they lived in her home town but after losing their first child, William, in 1841, they moved to Preston. James was to become the third eldest of their seven surviving children and after his birth they returned to Bolton.

In the 1851 census return, James Billington senior’s profession was listed as ‘labourer’. However, his son had no plans to follow in his father’s footsteps; instead the eleven-year-old boy built a replica gallows in the family’s backyard and imagined himself in the executioner’s role. He made dummies and practiced hanging them. He was still too young to have developed any sense of duty or strong beliefs in the use of capital punishment, yet he clearly felt a strong attraction to the only profession where an appointment with the incumbent would be an appointment with death.

Until 1874, the country’s principal executioner had been William Calcraft who had been over seventy years old when he had conducted his last execution, making Billington a comparatively young hand. During Calcraft’s period in office he executed over 400 prisoners. He may have been James’ inspiration during his early years, but it was his successor, William Marwood, who set the standard that James Billington would need to match.

Marwood introduced the more humane ‘long drop’ method which lead to an almost instantaneous death. Calcraft’s ‘short drop’ executions left him with the reputation of being a botcher, as it often resulted in the prisoner dying through strangulation, whereas the ‘long drop’ method resulted in prisoners’ necks breaking. Death was still caused by asphyxiation, but this occurred while the prisoner was unconscious.

Marwood died in 1883 and James Billington was quick to apply for the post. However, there were over 1,400 other applications and Marwood’s former assistant Bartholomew Binns was initially appointed, then replaced in 1884 by James Berry. Undeterred, Billington contacted the prison authorities and was invited to York to outline his method.

Despite Berry being a Yorkshire man and holding the position as the Home Office’s principal executioner, Billington successfully convinced the authorities that he should be appointed as executioner for Yorkshire. When the morning of Laycock’s execution dawned, it was the opportunity Billington had sought since childhood and he would have been determined to see nothing go awry.

The Industrial Revolution was the backdrop to James Billington’s formative years. It had dictated the fortunes of the earlier generations of his family and was still rolling forward with sufficient momentum to dominate the futures of the Lancashire communities.

The county of Lancashire lies about 200 miles north of London with the Irish Sea on its west coast, the Pennines on the east, with Cumbria to the north and Cheshire to the south. Before the Industrial Revolution, it was a relatively untouched corner of the country; its main industry was farming, arable in the lowland areas and sheep farming on the moors. The communities subsidised their livelihoods by hand weaving wool garments.

From the mid-nineteenth century, cotton supplanted wool as the most in-demand textile, and Lancashire, with its ideal moist climate for handling cotton threads, found itself with a supply of experienced weavers. Mills sprang up as the industry grew and the power of the streams and rivers was harnessed to run them. With the development of the steam engine mines flourished, tapping into local reserves of coal.

By the time James Billington was born in 1847, the once rural county was the home of rapidly expanding city slums and a burgeoning population. Bolton was made up of eight towns: Blackrod, Farnworth, Horwich, Kearsley, Little Lever, South Turton, Westhoughton, and Bolton itself. Bolton’s population grew from 17,400 in 1801 to 60,300 in 1851. Manchester, less than fifteen miles away, saw an even greater growth rate as its population swelled from 88,500 to 455,500 in the same period.

This unprecedented growth was driven by the textile industry’s need for cheap labour, and overwhelmed the unsophisticated existing infrastructure. Houses were shoddily built and crammed together, often shared by more than one family. It was common practice for people to work, and sleep, in shifts and cram ten or more into a single bedroom. There were no building regulations: floors were earth, there was no running water and houses were mostly built back-to-back with no gardens. Toilet facilities were shared by up to 100 houses and were either in the form of a privy, a deep hole, or a midden, the human equivalent to a manure heap piled against a wall.

With no damp courses, the rooms were perpetually wet; in some cases cellars were built to alleviate this dampness, but such was the level of poverty and housing shortage that these were very quickly sublet. The cellar population, in particular, suffered terrible ill health; cholera was common in the summer and sewage was often washed in during rainy periods.

In the cities, air pollution caused respiratory diseases such as pneumonia, bronchitis and asthma. Mill workers were particularly badly affected as these diseases were brought on by the high levels of cotton dust particles in the workplace. Levels of poverty were higher in Manchester than the notorious slums of London’s East End. In some parts of Manchester a working man’s life expectancy was just seventeen years.

In 1842, the sanitary reformer Edwin Chadwick wrote, ‘It is an appalling fact that, of all who are born of the labouring classes in Manchester, more than 57 per cent die before they attain five years of age.’ In an environment of poor sanitation, minimal hygiene, unclean water supply, terrible diet and overwork, the biggest killer of children was diarrhoea.

Of course, Billington survived his early childhood, but his working future was not bright either. In the 1800s working days of up to fifteen hours was commonplace and virtually all ages were recruited. Some babies were drugged with laudanum so that their mothers could work and children barely old enough to start school were recruited as mill apprentices.

Allan Clarke, the Lancashire Labour man, wrote in his book The Effects of the Factory System:

I see the little innocents rudely dragged from bed to be pitched into the factories at the early age of three and four; I see them stunted, sickly, with sad eyes imploring mercy from parents and masters in vain. I see them pining, failing, falling, struggling against hell and death, knowing not what to do for relief, knowing not where to ask for aid, dying by agonising inches, and blest when the end comes.

Children were often recruited at the age of six or seven. Apprenticeships usually lasted until the child reached the age of twenty-one, making it possible that a worker reaching twenty-one could have completed the equivalent of thirty years’ work under modern conditions.

By the mid-1800s many children had schooling in the mornings and worked in the afternoons. Even when education became more widely available, children still left school at twelve years old and it was standard practice for them to start work straight away, often as an apprentice. James Billington became a ‘little piecer’ at a mill, a job which was often given to the youngest children and was also known as being a ‘scavenger’.

David Rowland worked at a textile mill in Manchester and was interviewed by the House of Commons Committee in 1832. He explained the role:

The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught.

Many scavengers died by getting caught in machinery and many more were crippled from long hours of crouching.

The textile industry was the area’s main employer but it suffered from a cycle of boom and bust. Workers would often have their pay cut despite it already being well below subsistence level. During some of these depressed periods, emergency supplies of soup and blankets were distributed amongst the poor.

In the years before Billington’s first job in the mills some minor improvements had been made to working conditions: A new Liberal government took office in 1847 and introduced the Ten Hours Bill, which limited the working hours for women and children. The following year it introduced the 1848 Public Health Act, which gave Edwin Chadwick the opportunity to implement some of his sanitation ideas. These included citizens having access to clean water and the removal of sewage to farms where it was used as a cheap form of fertiliser.

While the new social reforms were slowly improving the lives of Lancastrian workers, elsewhere change was more swift. Revolutions were occurring in transport, communications, medicine and science. The world’s first railway station had been opened in Manchester in 1830 and it was now possible to travel quickly from Manchester to London. Inventors, engineers and scientists were developing everything from cars, aircraft, telephones, cameras and the postal system to vaccines, lifts and dynamite.

Another Lancashire man, Sir Robert Peel (1788–1850), had not only been Prime Minister but had created the London Metropolitan Police Force and introduced the Nine Points of Policing which are the foundation principles for modern policing.

For anyone with a little vision and the capabilities of staying out of the dregs of slum life, there were opportunities to be found. The following is a letter James Billington wrote to the Sheriff of Nottingham in 1884. It is reproduced here verbatim, and demonstrates that Billington had a basic education but, just as importantly, a clear vision of the career he wanted:

Sir I have seen it in the paper to-day that there as been a murder here (Nottingham) and having been in communication with the High Sheriff under Sheriff Chaplin and governor of Armley gaol Leeds in Yorkshire I have been examined with them for the post of hangman and the next that is hung there I have to do it. they could see that my system was better than the last and they was pleased with it. it prevents all mistakes as to the rope catching there [sic] arms and it will answer for 2 or 3 as well as one. you will find it to improve on the old system a great deal and I could put it to the old scaffold in about one hour. It is no cumbrance and it can be removed with the other part of the scaffold. they engaged me before Berry but it has been kept quiet and I thought if you had not elected one I should be ready at your call – if it was your will. you have no need to be afraid you may depend on me. I shall have no assistance I can do the work myself I don’t think it needs two to do the work and as long as they can have a little assistance from the gaol if required. I am a teetotaller ten years and a Sunday school teacher over 8 years, and if you like to see my testimonials if you will write to me I will send them or to Mr Gray he has a copy of them.

James Billington’s childhood was not as impoverished as those of many of the children growing up in Lancashire in the 1840s and ’50s, where the poorest groups tended to be communities of immigrants. Nevertheless, he and his peers would have grown up with first-hand experience of infant mortality, disease, malnutrition and squalor. Most of the early deaths in the area could be directly attributed to the greed and negligence of businessmen and government, in this scenario ‘playing hangman’ was not such a morbid game.

By the time of Billington’s first engagement he was a man with all the responsibilities of a large family. His older brother was John, who married Ann Sweetlove in 1869. At the time of the 1871 census they were living at 21 Smith Street, Bolton, with their baby daughter and a twenty-one-year-old visitor, a widow named Alice Pennington (née Kirkham). She was soon introduced to James and the two married on 8 April 1872 in the parish church of Bolton-le-Moors.

Both James senior and his son John were in the hairdressing trade, but James junior’s profession was recorded as ‘self-acting minder’.1 James was determined to find opportunity for himself and to avoid an impoverished upbringing for his children.

James and Alice’s first child, Thomas, was born in 1873, followed by William in 1875, John in 1880, Alice in 1883, Mary Ann in 1885 and James in 1887. According to some reports, they also lost another two children in infancy.

Endnote

1 Watched and minded the ‘Self-Acting Mule’, the name of a multi-thread spinning machine. The original Mule was hand-operated and was invented by Samuel Crompton of Bolton in 1779. It was made self-acting by Richard Roberts in 1830.

CHAPTER TWO

‘WORSE THAN HELEN’

The house in Back Lane. (Author’s collection)

There was a gap of three years between the first execution Billington conducted in August 1884 and the second in 1887, but from then until the end of Berry’s reign in 1891 Billington established himself as the executioner for Yorkshire.

This regional role served as an apprenticeship for his subsequent arrival as number one. Through this period the executions increased in both frequency and complexity, culminating in a final case that was described by the judge as ‘one of the most frightful atrocities that had ever been made public’.

Billington conducted eight executions during this period, beginning with the hanging of fifty-four-year-old Henry Hobson on 22 August 1887.

Hobson had been in the army for fourteen years, during which time he had been awarded three good conduct badges. After leaving in 1875 he took up employment at a Sheffield engineering works owned by the Stothard family. He held the position of engine tenter until September 1886 when Mrs Stothard dismissed him for ‘drunkenness, incapacity and neglect of duty’. Over the following ten months he found it impossible to hold down regular employment. He started to drink more heavily and began to focus his bitterness towards the Stothard family.

John Henry Stothard was the son of the owners and married to Ada. John had his own business manufacturing horns but Ada was a familiar face at the Stothard works and knew Hobson by sight.

At just after half-past ten on the morning of Saturday 23 July 1887, ten months after Hobson’s dismissal, Ada was at home, her baby was asleep in its crib and she was busy working with her servant, Florence Moseley. The two women were in the kitchen when Hobson knocked on the door, asking for a drink of water.

Ada handed him the drink and added, ‘We haven’t anything else.’

He replied, ‘A drink of water will do,’ but returned fifteen minutes later asking for a piece of string. Ada went to find some, but as soon as she had left the room Hobson pulled out a knife and attacked Florence. She put her hand to her throat in an attempt to protect her neck, an action which undoubtedly saved her life, but left her with severe cuts to the shoulder and cheek and an almost severed thumb.

Ada was alerted by Florence’s screams and rushed back into the room. Hobson immediately abandoned his attack on the young girl and turned on Ada.

Florence ran through a passage that led from the house into the street and attracted the attention of Mr Hardy, a local greengrocer, who ran back into the passage and met Hobson coming towards him. Hobson pointed back into the house and said, ‘He’s just gone upstairs.’

Hardy and several neighbours entered the house and found Ada slumped in a corner bleeding heavily from three gashes to the throat. The baby was unharmed, but Ada died before she could receive any help. The police immediately launched a manhunt and posted some of Hobson’s former work colleagues, including a man named Pursglove, at local railway stations to help with identification.

At half-past one Hobson turned along Furnival Road. He had changed his coat and vest and was calmly walking towards Sheffield’s Victoria station. Pursglove spotted him and Hobson was arrested and charged.

At the subsequent trial Hobson pleaded ‘not guilty’. The only known motive for the crime was revenge for the loss of his job. However, the evidence against him, which included the testimony of Florence Moseley, was conclusive. He was found guilty and sentenced to death but continued to claim to be innocent until the end.

He was hanged at Armley Gaol, Leeds; Billington allowed a drop of 7ft 4in and death was instantaneous.

The year 1888 had the potential to be Billington’s busiest year to date when he was engaged to execute three murderers: Mary Holloway on Monday 21 May, followed by Dr Burke and James William Richardson in a double execution on the Tuesday morning. On his arrival in Leeds, Billington was informed that both Burke and Holloway had been reprieved.

In a parallel to the Hobson case this execution was also the result of a work related dispute. Richardson had worked for the Brick & Carbon Works in Barnsley until 21 March when he was dismissed by the foreman William Burridge. In a rage he went home and returned armed with a pistol, he asked to speak to Burridge and the two men went out into the works’ yard. A witness reported that Richardson was ‘highly agitated’ and moments later heard three shots.

Two of the bullets hit Burridge, one in the lower body and the second lodged in his skull. Richardson immediately commented that he ‘must’ve been mad’ and went willingly to the nearest police station. Burridge’s head injury proved to be fatal and he died on 1 April.

Despite Richardson’s remorse, the campaign to save him failed and the execution went ahead as scheduled. Richardson left behind a letter telling his wife that he loved her.

Billington conducted three executions in 1899, one on the first day of the year and his first double on the last. The men, Charles Bulmer, Frederick Brett and Robert West, had all committed similar crimes under similar circumstances: each had murdered his wife whilst drunk, and in each case the murder weapon was a knife. This was a blueprint for many of the Billington cases, usually triggered by the catalyst of either money troubles or jealousy. Often such domestic killings made minimal impact outside the local area but Brett managed to buck this trend. He cut the throat of his wife, Margaret, and on his arrest was widely quoted as saying, ‘I was only acting at Jack the Ripper.’ His apparently casual remark spawned minor headlines in newspapers as far afield as America. The Brett and West execution was Billington’s first double; he carried it out with no assistant and again without any hitch.

Billington’s next visit to Leeds was on 26 August 1890 for the execution of yet another wife murderer, James Harrison, who had beaten Hannah Harrison to death with a poker. Harrison was executed at the same time as Berry was hanging Frederick Davis in Birmingham.

There was a total of seventeen hangings during 1890, but it was an equally eventful year in James’ private life. Alice died; she was just forty years old and left James with six children to care for at their home in Manchester Road, Farnworth.

There is no indication that his personal problems led him to turn down any opportunity to officiate at an execution and on 30 December both Billington and Berry were again conducting simultaneous executions. Berry was in Liverpool to hang Thomas McDonald, an habitual offender found guilty of the murder of a schoolteacher, while Billington was engaged at York for the execution of thirty-two-year-old Robert Kitching.

The Kitching case was followed closely by national as well as regional papers. The victim, Sergeant James Weedy, was a policeman with twenty years’ service and a reputation for bravery. He was also a married man with nine children who had died as the result of a trivial event.

Kitching, Weedy and both their families lived in the village of Leeming Lane, on the border between Durham and York. On 19 September 1890, Kitching was drinking at the Leeming Bar public house when Sergeant Weedy noticed that Kitching had left his horse and cart unattended outside. Weedy went inside and spoke to Kitching, but Kitching was far too drunk and became abusive, threatening Weedy as well as other people before going home. At around 10.30 p.m. Kitching’s wife took herself and their children to a neighbour’s house for protection and shortly afterwards she heard a gunshot.

Weedy’s body was found the following morning close to Kitching’s house, he’d been shot through the neck from close range. Kitching had gone to some lengths to move the body and dispose of the weapon, but was arrested at Richmond Market later in the day. In many ways the case was straightforward, however a policeman dying in the line of duty coupled with the detailed accounts of Kitching’s attempts to cover his tracks gave Billington his first taste of a high profile case.

For a time Berry and Billington’s paths seemed linked by little more than a few coincidental dates, but it was a week and a day and five executions in August 1891 that saw the change in fortunes for both men’s hanging careers.

Four of these five executions were Berry’s: on 18 August he was engaged at Chelmsford, at Wandsworth on the 19th, then at Liverpool on the 20th and finally at Winchester on the 25th.

The man due to be hanged at Kirkdale Prison, Liverpool was John Conway, a ship’s fireman convicted of the murder of a ten-year-old boy, Nicholas Martin, whose body had been recovered from a bag found floating in Sandon Basin, Liverpool Docks.

The murder was horrific, but so was the execution.

Conway was sixty years old, and weighed 11st 2lb. Berry claimed that he had intended to allow a drop of 4ft 6in, but that he had been over-ruled by the prison doctor, Dr Barr. According to Berry, Barr preferred the long-drop and wanted Conway to be given 6ft 8in. The final compromise was a drop of exactly 6ft: enough to rupture the blood vessels in Conway’s neck and coming close to decapitating him. The ensuing spectacle was reported in detail, with Berry taking the brunt of the blame. One report in the Liverpool Daily Press stated:

The rope, looked at from the brink of the scaffold, was embedded deep into the flesh of Conway’s neck, like a saw in a piece of timber through which it has almost cut. It would have been better perhaps had a less drop been given, for Conway was an old man, and some allowance should have been made for wear and tear of human muscle …

… The sight was one of the most horrifying descriptions that has ever been seen at any execution at Kirkdale. The scene at the scaffold was enough to shock even those who are well-accustomed to those awful legal tragedies. There was a painful interval after Father Bronté had ceased to speak. The outpouring of Conway’s blood could be heard distinctly all over the room, and the pit became like a shambles.

Berry was deeply upset by what had occurred and left Kirkdale before the inquest at which the prison Governor, Major Knox, insisted that everything had been handled without a hitch. Conway was buried within the prison precincts on the same day but the press, who had not been allowed to view the body on this occasion, continued to vilify Berry. He was said to have hurried Conway’s execution, behaving in a ‘rude, officious and cruel’ manner, even that he had pinioned the prisoner too tightly. After that execution Berry decided to resign, but he was left with one English execution to which he had already committed himself. Berry executed wife murderer Edward Fawcett at Winchester on 25 August, then retired, leaving the path clear for James Billington to fulfil his longtime ambition of being number one.1

The only Billington execution during those fateful eight days took place at Leeds, and the crime which precipitated his final execution as Yorkshire hangman was possibly only matched in horror by that which had precipitated the first.

Barbara Whitham Waterhouse was the daughter of David and Elizabeth Waterhouse and was five years and five months old. The family lived in Alma Yard in Horsforth. Saturday 6 June 1891 started the same as many others with Barbara eating breakfast at around 9 a.m. then going out to play in the yard. She was described by her mother as healthy, strong and well nourished. Her mother saw her at around noon but shortly afterward realised that her daughter was missing. She was not immediately alarmed but began searching for her straight away. Barbara had never strayed before and as she had no money when she disappeared it seemed unlikely that she would attempt a trip to the shops. Barbara was not particularly fond of sweets and Elizabeth felt it was very unlikely that someone could have enticed her daughter away by offering her anything.

Elizabeth and David Waterhouse spent the afternoon scouring the neighbourhood and informed the police. They searched any unlocked yards that Barbara might have wandered in to, but saw no sign of her.

As news spread of her disappearance people came forward to report sightings. Elizabeth’s cousin, Joshua Witham, had seen Barbara at about 12.45 p.m., she had been walking away from her home, and in the direction of some of the shops. When he’d seen her she was almost outside Dean’s Boot Shop, he described her as ‘alone and quite cheerful.’

Butcher’s son, Thompson Bussey saw Barbara at 1.30 p.m.; he was a school monitor and recognised her. When he noticed her she was standing outside the grocer’s shop with a little girl named Ethel Witham. From there he saw them walk towards the post office and the last thing he noticed was the two girls stopping outside.

Later, Eleanor Pointon, a trustworthy but vague witness, recalled that she had last seen Barbara on either 5 or 6 June, and at either 10.30 a.m. or 1 p.m. Eleanor had been working behind the counter in her father’s sweet shop at the time and Barbara had come in to buy one or two ham sandwiches, while another child had been waiting outside for her.

Thompson and Eleanor’s information was tied together by Mrs Witham, mother of a child named Emily. Thompson had been mistaken about the second child’s name and Eleanor had been vague about almost everything else, but Mrs Witham explained that she had sent her daughter, who was only three years old, on an errand to buy sandwiches from Mr Pointon’s shop. The Whithams lived near the Waterhouses in Alma Yard, and they knew Barbara. It was in the days after her disappearance that Emily told her mother that ‘Barbara went with me’. Mrs Witham said that her daughter had left home at about 1 p.m. and had returned within ten minutes.

There were no other sightings of little Barbara.

As her mother searched the streets there was one person that she remembered seeing on several occasions, a local woman that she knew only by sight. Her name was Mrs Ann Turner and she lived with her son, Walter, at 1 Back Lane, Horsforth. Mrs Waterhouse had no recollection of seeing Walter that afternoon and no one searched the Turner’s yard, which was always kept locked. In those first hours there was no reason for suspicion to fall on the Turner family.

Walter Turner was a thirty-two-year-old mill worker. He had started renting the house in Back Lane in March 1891, which was when his mother began to live with him. Ann was a widow and Walter was separated from his wife Helen. The house was a former pub and stood out because it still had the bracket on the wall from which the pub sign had once hung.

Neither Ann nor Walter was happy with the accommodation and complained about damp and rats. On the morning of Barbara’s disappearance one of Mrs Turner’s visits was to Mary Ann Robinson, wife of Abraham Robinson, who was the owner of the Back Lane property. When Mrs Turner stopped by at 12.30 p.m. to pay her rent, she also asked whether she could look at another house that the Robinson’s had available. She viewed this and told Mrs Robinson that she would speak to Walter and let her know on Monday.

Ann then made the six-mile trip into Leeds to visit her daughter’s family and also a friend, Mary Cotterill. Ann’s daughter, Jesse Maria, was deaf and married to a deaf and dumb man named Thomas Joy. He was a bookbinder by trade and had a small workshop at their home in Crown Street, Leeds. Jesse and Thomas had been married for almost fifteen years and had a son, George.

Ann arrived just after 3 p.m. and spent the afternoon with the family, shopping with her daughter before leaving for home at about 5 p.m. She brought George back with her and the two of them arrived in Horsforth around 8 p.m.

Walter was home and everything seemed normal, although George noticed that the settee was not in its usual position but had been moved across the cellar door. At 10 p.m. they went to bed, George sharing a room with his uncle and Ann taking the other bedroom.

When George woke in the morning, Walter was already downstairs with a fire burning in the hearth and extra coal in a coal box near the cellar door. George couldn’t remember seeing the Turners use a coal box before, but with his uncle lying on the settee and the settee blocking the cellar door he assumed this was just a more convenient way of tending to the fire.

When Ann woke she took her grandson for a walk to the nearby woods. They were gone for about two hours, during which time they assumed Walter stayed at home. In fact, Walter’s whereabouts could not be confirmed during that period or, more importantly, throughout most of the previous day. It seems Ann had no suspicions at this point, even though the Turner family was keeping a very telling secret about his past.

On Saturday 6 June Walter Turner had not turned up for work, the last time his co-workers, Elizabeth Kemp and Sarah Jane Gaulter, had seen him had been on Friday the 5th when, as usual, he had worked at the next loom. He hadn’t seemed unwell and they had no idea why he had not arrived for the Saturday shift.

Turner was later described as bearded and ‘considerably under the average size, and slight of frame; but his head is large, and his forehead especially high’. He was slightly cocky by nature, but not in a talkative way, rather someone who remained detached and unconcerned. He had previously been in court on a relatively minor charge in 1889 and reporters at the time observed that he appeared cool and indifferent.

In fact his calm appearance in 1889 hid the fact that his private life was in turmoil and in the summer of 1890 his wife, Helen, left him. She fled to America, preferring to start a new life there after Walter had attempted to murder her. No charges were brought, but Ann and Jesse were both well aware of the violent streak that Walter Turner possessed.

Mrs Turner returned to her landlord and landlady first thing on Monday 8 June and asked for the key to the new house, telling Mrs Robinson that she and Walter planned to move their things in that afternoon. At around 3 p.m. Walter and Ann were seen moving a tin trunk between the two properties.

On Wednesday 10 June Ann Turner visited Mary Cotterill, the two women had known each other for almost twenty years and Mary was someone that Ann felt she could confide in. While Mary’s children were still in the room Ann stayed silent, but Mary could tell that something was distressing her friend and sent them out to play. She asked Ann what was wrong several times before Ann replied, ‘There’s been nothing less than murder in our house.’

‘Is it the missing child at Horsforth?’ Mary asked.

‘I suppose it isn’t or it is,’ was the cryptic reply.

Knowing Ann had been in Leeds on the previous Saturday, Mary stated, ‘It is impossible for you to have had anything to do with this.’

‘I am as innocent as you are,’ Ann claimed.

She then went on to explain that she had gone into her coal cellar early on Monday morning and found a ‘bundle’, she touched it and realised in horror that it was a body. Walter heard her scream and assured her, ‘It is nothing I have done.’ He claimed the murder had been committed by someone named Jack with whom he’d been drinking.

Ann said that although she had kept it secret she had neither eaten nor slept, and to Mary’s horror told her that she had purchased some chloride of lime which she had placed on the body to mask the smell. She then said, ‘We’ve brought it down in a tin box to Tom’s shop in Leeds.’

Mrs Cotterill and her husband advised Ann to contact the police and, although promising to do so, she in fact returned to the Joys’ house just after 9 p.m. and had another conversation with Walter.

Jesse could sense that her mother was distressed and, using sign language, asked her what was wrong. Ann spelt out her reply: ‘I won’t tell you, it’s worse than Helen.’

In the end Walter and Ann then carried the trunk through the centre, towards the Town Hall. Ann hung back as Walter abandoned its contents at the gates of the Municipal Buildings in Alexander Street. They returned to the Joys’ house. The next morning George was offered the empty trunk, but he said he didn’t want it. Ann then cleaned it thoroughly with a duster which she then burnt.

Barbara Waterhouse’s body was discovered by PC William Moss at 11.40 p.m. on Wednesday 10 June. She was wrapped in a shawl. Her body was carried to the Town Hall and the police surgeon was summoned. He noted that the child was fully dressed, and that the clothes had not been cut or disarranged in any way. Despite this, her body had suffered substantial knife wounds.

By 12 June it seems that the stress of keeping Walter’s terrible secret had become too much of a burden for Ann Turner. She arrived at the Leeds detective office and made a statement to the officer on duty, Inspector Sowerby, which read:

I have a son named Walter Turner, thirty-two years of age, a weaver by trade who works at Messrs Lonsdale’s Mill, Horsforth. On Monday last I noticed a bundle in the coal-house under the stairs in my house. It was wrapped in the shawl shown to me now, which is my property. I was from home on Saturday last. On Monday I asked my son what was in the bundle. He replied, ‘I’ll tell you sometime. It’s nothing I have done.’ I did not look inside the bundle though I touched it. I thought something was wrong. I had used the shawl on my son’s bed. My son Walter was in Leeds some time on Wednesday evenings. On Wednesday night I was with him. We brought the bundle with us and left in the street in the heart of the Town Hall. We then walked home, and arrived about 1 o’clock. We brought the bundle in a tin box to Leeds and left the box at the railway station. I have not seen it since.

Inspector Sowerby and a colleague, DS MacKenzie, took Mrs Turner to Midland station where they found the tin box, they then returned via the Municipal Buildings where she also identified the spot where the body had been left. As a result of this both Ann and Walter Turner were arrested. When she was charged Ann said, ‘There is no doubt it was done on Saturday, I have no hesitation in saying so, but I know no more about it than any of you.’

The trial of Walter and Ann Turner began on 30 July 1891 at Leeds Assizes with Mr Justice Grantham presiding, Mr Charles Mellor, leading counsel for the defence, and Mr Harold Thomas, counsel for the prosecution.

Mr Charles Mellor initially argued that there was insufficient evidence to charge the prisoners with murder and suggested that the charge should be altered to being ‘accessories after the fact’. After some debate the judge decided that they should be first tried with being accessories and if found guilty they could subsequently be tried for murder. Mr Mellor persuaded the judge that the prisoners should be tried separately, and Ann Turner was tried first on a charge ‘that she did feloniously receive, harbour, maintain and assist the murder and removal of the body’. That Ann Turner knew that there was a body, firstly in her house and secondly in the trunk that she and Walter were moving, was never disputed.

During the trial, Mr Cotterill’s statement showed that Ann Turner’s admission to the police had not been wholly brought about by the burden of keeping Walter’s secret. She had visited the Cotterills on 8 June and for a second time on 10 June. On the first visit she had promised to contact the police so, on 10 June, when she admitted to Mr Cotterill that she had done nothing, he told her that she had to go immediately to the police otherwise he would. There was a gap of only a couple of hours between his threat and her arrival at the police station.

Ann Turner also claimed that part of her reason for trying to conceal the crime was the fear that local people would lynch them if they heard that she and her son were involved. There was no evidence put forward to support this. She had taken an active part in disposing of Barbara Waterhouse’s body, so it was a doomed argument from her defence counsel, who tried to convince the jury that her only offence was allowing her ‘great maternal love’ to motivate her into trying to protect her son.

After Ann Turner was found guilty the judge told her that she had been ‘found guilty of one of the most serious crimes known to the law. This was aiding and abetting in one of the most frightful atrocities that had ever been made public.’ He disagreed with the recommendation for leniency that had come from the jury and imposed the full penalty of penal servitude for life.

Some members of the public applauded, while Ann Turner herself appeared shocked by the severity of the sentence and had to be helped back into a chair by a female warder. The Leeds Evening Express inaccurately stated that Ann Turner was due for release in August 1892; she died in prison.

The following day Ann Turner was brought before the court again, this time on the charge of murder. She was asked to choose whether or not she was prepared to testify against her son; refusal to do so would incriminate her, but her co-operation would guarantee that she would be acquitted. She agreed to testify and the murder charge against her was immediately dropped.

Walter Turner chose to plead ‘not guilty’ and a new jury was sworn in. Prosecution counsel, Harold Thomas, admitted that the evidence was largely circumstantial but impressed upon the jury that they needed to be completely satisfied that Walter Turner was the only person who could have committed the murder.

When Ann took the stand she avoided giving direct answers to most of the questions put to her and her testimony added nothing further to the case against her son. This new jury then heard from the Cotterills, the Joys and several other witnesses who had given evidence at Ann Turner’s trial. One new witness was Mr Ed Ward, the police surgeon who, for the first time, detailed the injuries to Barbara Waterhouse.

There were forty-six different cuts and stab wounds to the chest, but only three of these showed any sign of bleeding. One of these, a deep wound of between 15in and 18in long, extending from the neck down through the front of the body, had been the cause of death. Initially, the time of death was thought to be less than sixty hours before the discovery of the body, i.e. just a few hours before Ann discovered the body in her own home. However, after an examination of the Turner’s cellar and consideration of the weather at the time, it was decided that Barbara’s death could have occurred almost immediately after her disappearance.

Mr Ward went on to say:

On the surface of the body and the clothing and in some of the wounds was a soft white substance which was found to be chloride of lime. The muscles were completely divided in each groin, and there was a long wound on the inner side of each thigh. There were some wounds in the liver which must have been done after the body was opened. Externally the private parts of the body were mutilated almost out of recognition. There was a large wound beginning at the root of the neck which went along the middle line of the body, completely dividing it. This had the appearance of a continuous wound but had probably been inflicted in two cuts. There were two stabs over the region of the heart which might have bled. The wounds might have been inflicted with a knife having a blade two inches long, half an inch wide and having one sharp edge.

In the stomach of the child was part of an orange, which did not seem to have been in the stomach more than an hour before death. From the wounds there must have been 3lb of blood, which would be nearly half a gallon, and there must have been a great quantity of blood left somewhere. The cause of death was haemorrhage from the large wound in the chest.

Mr Ward had examined floorboards taken up from both of the Turner houses and did not think that Barbara Waterhouse could have been killed at either; in his opinion it would have been impossible for the killer, certainly a lone killer, to have avoided substantial bloodstains. He felt it was far more likely that the murder had occurred elsewhere. If it had taken place outside he felt confident that the killer could have acted alone. One stained floorboard from the Turner’s house was examined; it had been scrubbed but still bore a dark red stain, possibly in the shape of a boot print. Unfortunately the mark was too faint for the forensic tests of the day to determine whether it was made by blood.

Mellor summed up in Turner’s defence. He asked the jury to consider three major deficits in the prosecution’s case. Firstly, that there was no proof that Turner had had any contact with Barbara Waterhouse before her death, Turner was not known to the girl and there was no reason to believe that he had given her the orange to eat. Secondly, numerous sightings of Barbara proved that she was still alive and well after lunch on 6 June, but the prosecution could not produce a witness who could show that Walter Turner had left home at all after 10 a.m. Thirdly, no motive had been put forward for the crime.

This final point was not completely accurate, the prosecution had raised the point that one particular wound had been inflicted in the genital area, either as part of a sexual assault or by a knife. As the knife may have caused the wound, they were not totally confident in assuming the motive had been sexual. They did not offer an alternative motive.

The great lengths that Turner had gone to in order to hide and dispose of the body convinced the jury that he was guilty and the judge passed the death sentence. Turner remained unemotional until the end, neither protesting his innocence nor confessing.

James Billington arrived in Leeds on Monday 17 August, he immediately reported to the Governor, Major Lane, and together they made an inspection of the scaffold. The following morning at 8 a.m. Turner took the short walk from the condemned cell to the gallows. Press representatives were not permitted at the execution, just gaol officials and three borough justices. Billington allowed a drop of 8ft and death was instantaneous. Turner supposedly left behind a note claiming that he had been drugged with beer and that someone else had committed the murder, but no credibility was ever attached to this.

Endnote

1 This was Berry’s last execution in England, but he went on to conduct one further execution in the British Isles.

CHAPTER THREE

‘HE NEVER HAD A DREAM IN HIS LIFE’

Signature of Henry Dainton. (Courtesy of the Dainton family)

In the 1891 census return James Billington was recorded as being a widower. His profession was listed as barber. His eldest son Thomas had married Alice Platt in September 1890 and was working for his father and living in Market Street, Farnworth, above the family business. William was sixteen years old and an apprentice blacksmith. He lived with James as did the other four children and James’ thirteen-year-old niece, Mary Slater.

Running a home, a business and travelling away from home would have presented James with difficulties best solved by remarrying at the earliest opportunity. He wasted no time and married Alice Fletcher on 7 July 1891. Their marriage certificate shows that they were living together at the time of the wedding so it is possible that she moved back to her parents’ home on census day for the sake of propriety. Alice’s father was a coal miner and she worked at the local cotton mill until she married Billington. Alice and James had just one child together; May was born in 1900 when Alice was forty years old. Interestingly, her age at the time of her marriage was recorded as thirty-five, but exactly ten years later on the 1901 census as forty-one. In light of her giving birth in 1900 it seems more likely that she was born in 1860 than 1856.