Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

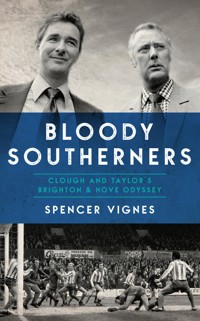

In 1973, Brian Clough and Peter Taylor stunned the football world by taking charge of Brighton & Hove Albion, a sleepy backwater club that had rarely done anything in its 72-year existence to trouble the headline writers. The move made no sense. Clough was managerial gold dust, having led Derby County to the Football League title and the semi-finals of the European Cup. He and his sidekick Peter Taylor could have gone anywhere. Instead they chose Brighton, sixth bottom of the old Third Division. Featuring never-before-told stories from the players who were there, Bloody Southerners lifts the lid for the first time on what remains the strangest managerial appointment in post-war English football, one that would push Clough and Taylor's friendship and close working relationship to breaking point.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BLOODY SOUTHERNERS

CLOUGH AND TAYLOR’S BRIGHTON & HOVE ODYSSEY

SPENCER VIGNES

In memory of Roy Chuter, Paul Lewis and Steve Piper – three fine football men of Southwick, St Athan and Worthing respectively, gone too soon.

‘These are the times that try men’s souls.’

THOMAS PAINE, THE AMERICAN CRISIS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

There is, as I write, only one club among the ninety-two members of England’s four elite football leagues that carries the name of two places in its title. Born out of a gathering held at the Seven Stars Hotel in Ship Street, Brighton, on 24 June 1901, Brighton & Hove Albion are regarded now as the kind of forward-thinking, dynamic animal that most soccer managers would jump at the chance of helming. Home is an aesthetically pleasing stadium packed with around 30,000 supporters every other week. Awards have been won for the club’s pioneering work in the local community. The training compound is among the best in Britain. They will never be Manchester United or Liverpool, but, equally, ‘Albion’, as supporters tend to call them, are light years away from the cash-strapped Burys and Newport Countys of the English and Welsh professional game.

It wasn’t always like this. For seventy-two years, Albion skulked around in what might kindly be described as the game’s shadows, rarely doing anything of excitement to trouble the headline writers. Comedy relief was quite literally provided by Norman Wisdom, who, between 1964 and 1970, served on ‘a committee that talked about things’, as the late comedian once described the club’s board to me. Training took place among the dog mess on Hove Park. If Brighton was a town that looked, according to the playwright Keith Waterhouse, like ‘it is helping police with their enquiries’, then Albion could equally have been described as a football club of the tired, end-of-the-pier variety.

And then Brian Clough walked in.

Just imagine Alex Ferguson quitting Manchester United during the high-water mark of his reign at Old Trafford to take over at Rochdale. Or José Mourinho walking out on Chelsea in the wake of the 2015 Premier League title triumph and joining Southend United. Scenarios like that don’t tend to happen in life, let alone football, going against the grain when it comes to the upward career trajectories of anyone with a drop of ambition in their veins.

Except that, in November 1973, one did.

At that time Brian Clough was managerial gold dust, having led Derby County from the old Second Division to the 1971/72 Football League title. The following season, County reached the semi-finals of the European Cup, controversially exiting the competition to Juventus amid rumours of bribery and corruption concerning the referee appointed for the tie’s first leg. Clough’s maverick ways, success at club level and made-for-television soundbites meant he was the perpetual people’s choice as next boss of the England national team. And yet the man who would later declare himself (maybe with a hint of tongue in cheek, maybe not) to be ‘in the top one’ of managers chose to join a club six places from the bottom of English football’s Third Division.

As a journalist I had recalled Clough’s improbable spell at Brighton & Hove Albion across a combination of newspapers, magazines and the club’s official match-day programme, where for many years I have served as a feature writer. I met many of the players who were there, getting to know some as friends, and would never tire of hearing their stories about Clough, whose death in 2004 has done little to diminish his status as one of English football’s iconic figures. Some of those stories showed him in a positive light, others not so, as you might expect of a true original who revelled in dividing opinion. But they were never dull. That in itself leaves me scratching my head as to why it took so long to think of this remarkable sporting odyssey as a book. Sometimes the best ideas are staring you in the face the whole time.

Is the world ready for another book about Brian Clough? That’s a question I asked myself several times before committing pen to paper, or rather hand to laptop. The answer always remained the same, and here’s why. Every nook of Clough’s career both as a player and manager has been thoroughly dissected on celluloid and in book form, with one exception – nobody has ever focused solely on his time at Brighton & Hove Albion. In many ways, that’s the most intriguing part. What motivates a man at the top of his game to take a job which appears so monstrously beneath him? It made little sense back in 1973, even allowing for Clough’s trademark eccentricities. It makes more sense to me now that I’ve researched and written this book. Even so, no matter how I probed Clough’s thought processes for logic, the whole affair has the word ‘surreal’ written through it like a stick of Brighton Rock.

What’s more, as good as the majority of books, films and documentaries about Old Big Head have been, I’ve found myself becoming increasingly riled at the degree of artistic licence taken with elements of the Brian Clough story. The footnote traditionally occupied by Brighton & Hove Albion tells of a club low on resources and going nowhere. That simply isn’t true. After seventy-two years on skid row, Albion had an ambitious new chairman in place who was prepared to spend money. Lots of it. In fact, Mike Bamber, for that was his name, would part with more cash in transfer fees during Clough’s nine months in charge than any other chairman outside the First Division (the equivalent of today’s Premier League), not to mention several inside it.

It has also become de rigueur to talk up Clough’s admittedly remarkable achievements at Nottingham Forest by playing down the stature of the East Midlands club that he inherited in January 1975, six months after his departure from Brighton and following an ill-fated 44-day spell as manager of Leeds United. In 1967, Forest had come within touching distance of winning the Football League and FA Cup double. That would have been their third FA Cup triumph, the second having arrived as recently as 1959. Forest may have been in the doldrums when Clough took over, but such a CV doesn’t square with my understanding of what constitutes a small provincial football club. That, however, is what they have become in the creative rush to laud him.

This is the story of what happened when Brian Clough, together with his assistant, partner, shadow – call Peter Taylor whatever you will – went to manage a genuinely small provincial football club. In 1973, Albion had never finished higher than twelfth in the old Second Division or progressed beyond the fifth round of the FA Cup. But something was beginning to stir on the south coast of England. Clough would later argue that the task of achieving success at Brighton was ‘like asking Lester Piggott to win the Derby on a Skegness donkey’ – a quote which leads me to surmise that he either didn’t comprehend or didn’t wish to acknowledge the club’s untapped potential. Indeed, ‘What would have happened had Brian Clough stuck around?’ is a question that has long fascinated Albion supporters of a certain age, especially in light of what transpired at Nottingham Forest.

Brighton & Hove Albion was far from Brian Clough and Peter Taylor’s finest hour. It bore witness to the first major fracture in their relationship, a trial separation in a union that ultimately dissolved into acrimony, bitterness and regret despite yielding silverware aplenty. However, neither was their stint beside the seaside the complete washout it is often portrayed as. Quite the contrary. In fact, it would, in the long run, prove to be the making of a football club.

Spencer Vignes Cardiff, Wales September 2018

1

THE WHITE HART

Catalyst, rebel, man of the people, one-off, thinker, strong-willed, passionate, compassionate, revolutionary, independent of mind, academic underachiever, self-taught, visionary, quick-witted, complex, opinionated, difficult, controversial.

Almost certainly, Brian Clough would have got along famously with the idiosyncratic character who was Thomas Paine.

Before leaving England and emigrating to Philadelphia, where his writing championing a republican form of government under a written constitution played a pivotal role in rallying support for American independence, Paine spent six years from 1768 living in the town of Lewes, Sussex. Nestling beneath the protective arm of the rolling South Downs hills, Lewes already had form when it came to non-conformism. It was here, during the mid-sixteenth century, that seventeen Protestant martyrs were burned to death for their faith during the Marian persecutions of Queen Mary’s reign, or ‘Bloody Mary’ to her detractors. Every year on 5 November, in union with Guy Fawkes Night marking the uncovering of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot, local people continue to salute the martyrs amid raucous scenes. How else can one describe the enthusiastic torching of multiple effigies, including that of Pope Paul V, whose tenure coincided with the Plot?

Paine lodged over a tobacco shop, married his landlord’s daughter and became a member of the local debating society based at the White Hart Hotel in the High Street. There he honed the theories that formed the basis of his revolutionary politics. All of which gives the White Hart a pretty strong claim to be the cradle of American independence, as declared on a modest blue plaque now fixed to the front of the building.

As for the hotel’s other brush with fame? Well, you won’t find details about that on any plaque. It exists only in the memory of the people who were there, or at least those of them still alive. On Friday 2 November 1973, Brian Clough and Peter Taylor came to the White Hart to meet Brighton & Hove Albion’s players for the first time. And, to a man, it wasn’t an encounter any of them were likely to forget in a hurry.

The rumours had abounded all week – not that any of the players seriously believed them at first. Why would the self-proclaimed (albeit with good reason) best manager in the business be poised to join a Third Division football club? And a struggling Third Division club at that. Yet, with every passing day what had initially been dismissed among the squad as newspaper talk began to take on more substance. Then on the Thursday came confirmation: Brian Clough was Albion’s new manager, Peter Taylor his assistant.

The news was greeted by the players with a fusion of laughter, incredulity and genuine excitement as they gathered for training on Friday morning ahead of the following day’s home game against York City. There was also a message from the club’s chairman, Mike Bamber, awaiting them. After training, they were to return home, pack an overnight bag and make their way in smart attire to the White Hart for dinner and an introductory meeting with Clough and Taylor.

Come 4 p.m., eighteen members of Albion’s squad – a mix of seasoned professionals and younger players, plus a couple of youth team rookies – had gathered at the White Hart along with brothers Joe and Glen Wilson, both former Albion players who’d gone on to share a variety of roles within the club including trainer, kit man, scout and caretaker manager. All were escorted through to a dining room, where dinner was served. By 5 p.m., the food had long since disappeared, and still there was no sign of Clough or Taylor. Was this a deliberate ploy of theirs aimed at raising the suspense levels another couple of notches? Nobody knew.

The waiting continued. Striker Barry Bridges and left midfielder Peter O’Sullivan were half wishing Clough for one wouldn’t turn up at all. ‘I’d only ever seen him on television before and he’d always be doing his “Young man” thing,’ recalls O’Sullivan, once on Manchester United’s books as a teenager and regarded as Albion’s chief playmaker. ‘You know, “Young man, you should be doing this” and “Young man, you should be doing that.” I knew if he came in and said “Young man” even once then I’d be in trouble because I wouldn’t be able to keep a straight face. Barry was the same. That was nervous laughter, I can tell you. You don’t want to laugh but you can’t help it because of the situation you find yourself in.’

Like many hotels, the White Hart piped music through speakers into its communal areas supposedly for the benefit of guests – easy-going tracks such as Harry Secombe’s ‘If I Ruled the World’, which by some uncanny coincidence happened to be playing when, at long last, the door to the dining room opened and in walked Brian Clough, closely followed by Peter Taylor.

The good news for O’Sullivan was that the words ‘Young man’ didn’t so much as pass Clough’s lips. The bad news came in the form of his collar-length hair, a real no-no in the manager’s eyes, even circa 1973, when it was all the rage. Fortunately, Clough’s attention was drawn first to utility player John Templeman, whose flowing locks far outshone O’Sullivan’s.

‘He went straight to John and said, “I understand you’re called Shirley Temple because of your long blond hair,”’ remembers defender Steve Piper, whose twentieth birthday it was that day. ‘He had a right go at him. I’m sitting there thinking, “That’s not nice but at least while he’s on at John he can’t find fault in me.” But the hair was always going to be a thing with Clough.’

‘Yeah, he was quite sarcastic about it, put it that way,’ concurs Templeman, wincing at the memory.

What happened next came out of left field and caught everyone present off guard. ‘He [Clough] has shaken a few hands and said a few things to people,’ says Lammie Robertson, Albion’s resident Scotsman able to play up front or in midfield. ‘Suddenly he goes, “What do you want to drink?” And everyone’s looking at each other. One by one we start saying, “I’ll have an orange and lemonade,” “I’ll have an orange and lemonade,” and so on. And he goes, “I mean a drink!” So, we had to write down what we wanted to drink. I still had a soft drink, but I think a couple of the lads said, “I’ll have a pint” because that’s what he wanted to hear.’

‘That was like, “What the fuck do we do?”, because it was a Friday night,’ adds O’Sullivan. ‘We drank back then, of course we did, but you’re not supposed to be drinking the night before a game. I definitely had a beer along with one or two of the other guys, but most didn’t. I thought it would be rude not to. Brian certainly had a beer and Peter had something stupid like a Campari and soda. And then, like he’d done with John, he copped hold of me and told me to get my hair cut.’

Even the introduction of alcohol couldn’t dispel the uneasy atmosphere that now hung across the room, much as a sea mist carpets the Sussex coastline on a late spring morning. Many of those present, including Joe and Glen Wilson, were nervous about their futures now that a new management team was in place. Clough and Taylor were bound to want to make changes that could well extend to the backroom staff. The players knew it. Clough knew that they knew it. So, having addressed the unruly haircuts and attempted quite literally to inject some spirit into proceedings, his attention switched to the team in general.

‘My first impression was that he was a complete headcase,’ says Brian Powney, whose remarkable agility as a goalkeeper more than compensated for his slight stature, at least compared to the vast majority of other players in his position. ‘The things he was saying, and the way he was saying them, all delivered in that accent of his. He said, “If you’re lucky enough to be here next year, we will be going places.” What a thing to say to a team that’s going to go out and play for him tomorrow – “If you’re here next year.” That’s not exactly going to inspire, is it? And because he didn’t turn up until God knows when, that’s what we had to go to sleep on. Thanks for that – thanks a lot. Just incredible.’

‘Right from the very first, that’s what he was like,’ says Lammie Robertson. ‘You never knew what was going to happen next, what he was going to say, what he was going to do. He was an oddity from the start. And you know what? I think he loved being like that.’

2

A CHANGE IS GONNA COME

‘It was a hot afternoon, last day of June, and the sun was a demon.’

Bobby Goldsboro was right, at least from a Sussex point of view. The sun was indeed a demon on the last day of June 1973, just as his song ‘Summer (The First Time)’ – the tale of a seventeen-year-old boy’s sexual awakening at the hands of an older woman – began attracting the attention of disc jockeys on the eastern shores of the Atlantic Ocean. In fact, the sun was a demon in the skies over Sussex throughout most of June and July – good news for the thousands of day trippers and holidaymakers to the coast but agony as far as Frankie Howard, groundsman for over a decade at Albion’s antiquated yet homely Goldstone Ground, was concerned. A former left-winger with 219 appearances for the club to his name, Howard was the kind of man who spent more time tending his precious football pitch than his own garden. Sunshine was a good thing, up to a point. Now he, or rather his pride and joy, craved rain.

The last day of June 1973 fell on a Saturday. A day of rest for the majority, but not Frankie. Albion’s squad, having returned from their summer breaks for pre-season training, required the pitch for a workout on the Monday. Howard had expressed reservations, given the parched conditions, only to bow to manager Pat Saward’s wishes. The pitch wanted watering and that meant being there over the weekend to operate the sprinklers. Anything to help Saward – a man Howard respected and yet feared for. In May 1972, Albion had been promoted to the second tier of English football’s pyramid system for only the second time in the club’s history. The celebrations were short-lived. Thirteen consecutive defeats spanning November 1972 and January 1973 meant Saward’s men were doomed to relegation long before the final ball of the season was kicked. Howard knew that a decent start to the 1973/74 campaign was imperative or the manager would be out of a job. That’s the way it goes in a results-driven business when you’re not getting results. Some said Saward was lucky not to have been fired already.

The pitch needed water. The team desperately needed a lift. The club needed a manager who would provide that lift, be it Saward or a fresh face. Just as well, perhaps, that things were on a surer foot in the boardroom. In December 1972, Albion had made the somewhat unusual move of appointing two men – Mike Bamber and Len Stringer – to work as joint chairmen. Stringer, a local funeral director, would soon relinquish his position, leaving Bamber in sole charge. Partial to cigars, jazz and foreign holidays (hence his ‘Miami Mike’ nickname among some of the players), Bamber was a firm yet likeable businessman who, in the words of one former Albion director who worked alongside him, ‘seemed incapable of passing a pie without putting a finger in it’. He was a farmer. He was a property developer. He ran a restaurant that doubled as a nightclub. And he’d also formed a genuine attachment to the football club on the doorstep of his Hove mansion, the one that had under-performed so spectacularly throughout most of its existence.

For well over a century, right up until Crawley Town were promoted into the Football League in 2010, Brighton & Hove Albion stood alone as the only professional club in Sussex. The catchment area in terms of people who might want to watch a game of football was huge by English standards, the county’s borders encompassing 932,335 acres inhabited by a population of over 1.2 million people according to the 1971 census. The nearest Football League clubs to the north and west were Crystal Palace (forty-six miles) and Portsmouth (fifty miles) respectively. As for the south and east? Well, there weren’t any – at least not until you hit the French coast.

Mike Bamber wasn’t alone in noticing that on the rare occasions when Albion threatened to wake from its seemingly eternal slumber, so the people of Sussex had responded in impressive numbers. On 30 April 1958, more than 31,000 of them converged on the Goldstone to watch their local team gain promotion from the old Division Three (South) with a 6–0 win over Watford. Fourteen years later, more still were present to witness the 1–1 draw against Rochdale that confirmed the club’s return to English football’s second tier – 34,766 souls shoehorning themselves into a rickety old football ground completely at odds with its genteel surroundings in well-heeled, reserved Hove.

Others had acknowledged Albion’s potential but failed to do anything about it. So long as he was chairman, however, Bamber decided things would be different. Besides himself (few if any football chairmen, then as well as now, are bereft of an ego), Bamber recognised that the most important person at a football club was the manager. A better manager meant attracting better players. Better players meant a better standard of football. A better standard of football meant larger attendances. Larger attendances would not only sustain the whole operation financially but also open up the possibility of moving to a better ground. That, as Albion geared up for the 1973/74 season, was Bamber’s business model.

Was Pat Saward the man to spearhead Albion’s revolution? Len Stringer hadn’t thought so, disagreeing with the manager on virtually everything from team selection to the strength of the half-time tea. Bamber also remained unconvinced. He liked Saward, as stylish a dresser as he’d been an inside-forward during the 1950s for Aston Villa, and recognised the fine job he had done in guiding Albion to promotion in 1972. But the 1972/73 season had been shambolic. With Stringer poised to step down as co-chairman, Bamber chose to see how results panned out during the opening weeks of the 1973/74 campaign before deciding whether Saward was his man.

‘Pat was a very smart, articulate guy with a great presence, almost like a bit of a film star,’ says goalkeeper Brian Powney, Albion’s longest-serving player at the time, having joined the club’s ground staff as a fifteen-year-old in 1960. ‘He’d taken over from Freddie Goodwin, the previous manager, during the summer of 1970, and I soon realised he was a manager I wanted to play for – a very good coach who always joined in training. But when we got promoted [in 1972] he didn’t have any money to spend and we went straight down again. We struggled. I suppose he could well have got the sack then, but I for one was glad he was still there at the start of the [1973/74] season.’

‘The team that got promoted in 1972 was made of up twelve or thirteen guys who were the core of the side,’ says Ian Goodwin, a Goliath of a centre-back initially signed on loan from Coventry City by Saward during the 1970/71 season. ‘Then, having gone up, Pat decides [defender] Norman Gall isn’t going to be good enough, and that somebody needs to come into midfield because Barry Bridges is getting to the end of his career, and so on. One of the first games we played that season we lost 6–2 at Blackpool. I got booked twice and wasn’t sent off – nobody noticed – but that’s beside the point. Instead of standing by us, giving us the chance to dig ourselves out of the hole we’d created, he starts making changes – too many changes. We deserved an opportunity as a team for maybe half a dozen games or more, but we didn’t get it. Those changes, in my opinion, cost us our team spirit.’

‘I first broke into the side as a youngster during that disastrous season because he [Pat] made those wholesale changes to the team,’ says Steve Piper, signed on a semi-professional basis as an eighteen-year-old after impressing at centre-back for the local amateur club Rottingdean Victoria. ‘Maybe that was his downfall, making so many changes, but if he thought the players that he had weren’t good enough – and if he didn’t have any money to buy new ones – what else was he supposed to do other than throw in some youngsters? There was myself, [winger] Tony Towner and [striker] Pat Hilton who were brought in and the three of us were just teenagers. But in terms of being a coach Pat was second to none and a really nice man.’

Lammie Robertson was an exception to the rule. Pat Saward had managed to crowbar some cash from Albion’s coffers to buy the combative Scot who’d cut his teeth playing in defence, midfield and up front for Bury and Halifax Town. ‘We [Halifax] had played Brighton a couple of times and got beat at home in one game,’ says Robertson, signed by Albion in December 1972 for £17,000 plus a player swap; striker Willie Irvine went in the opposite direction to Halifax. ‘Pat told me afterwards that he liked my attitude. We’d got beat but I’d banged a wall in frustration and he remembered that. They [Albion] were struggling against relegation from the old Second Division and the philosophy was “We’re going to buy a lot of players and spend our way out of trouble.” But it never happened. I think it may only have been me who they actually paid money for. That was it. So we didn’t get out of it and got relegated. That pissed me off. It seemed as though a lot of the players were kind of giving up on it as well before we were actually down.’

That said, Robertson could see the club had potential. ‘It was a bit like going back to Burnley again where I’d started my career in English football but hadn’t cracked the first team. The ground was one of those places that could hold 25,000 or more, which Bury and Halifax weren’t. Even when we struggled against relegation the crowds hadn’t been too bad. There were some good players there as well like Sully [Peter O’Sullivan]. Great left foot, and a funny guy as well. We were playing up at Hull on a Friday night towards the end of that [1972/73] season and this official-looking guy came in the dressing room. I’d just got back in the team from an injury. Sully collared the guy and asked him if there were any changes. I wasn’t in the programme as I’d been injured. It was just “Robertson, number 10”, so the guy asked, “What’s his name?” And Sully goes, “Fyfe.” Now I don’t know if you remember but Fyfe Robertson used to be this old fella on the television who’d do the news and current-affairs programmes. And that’s what was announced by this guy over the tannoy before the game: “Changes, number 10 for Brighton, Fyfe Robertson!” That was Sully for you. A good lad, and a good player.’

With the exception of Mick Brown and Ronnie Howell, a defender and a midfielder signed over the summer months on free transfers from Crystal Palace and Swindon Town respectively, the Albion team that took to the field for the opening games of the 1973/74 season in the Football League’s Third Division (now League One) read exactly the same as the side that had been relegated a few months previously. Very little new blood, in other words, bought with zero pennies.

In his programme notes for the first home match of the season, a League Cup tie against Charlton Athletic on Wednesday 29 August, Saward was open about his own shortcomings as well as those of the team’s over the previous season. ‘It is factual, but unbelievable, that this time last year we were marching like gladiators to our first match in Division Two versus Bristol City, and the rest of the story is too painful to relate,’ he wrote in prose every bit as slick as his dress sense. ‘The relapse which followed our triumphant victory was inexplicable. Tenacity and determination were not lacking but I would be less than honest if I were to deny that these earlier performances were a disaster. I have made mistakes but at the time I firmly believed they were the only decisions. It is a manager’s unenviable task to envisage the future, not only of his club but all the other league clubs as well, and naturally the human element of wrong decisions is bound to happen from time to time. The important thing is to learn from these results and I have. Each season is a walk into the unknown but with our dedication and knowledge of last season I am quite confident that we shall be playing positive football this season which will be thoroughly enjoyable.’

To Frankie Howard’s chagrin, the sun continued to beat down on his prized turf as August made way for September. Even worse, his fears regarding Saward’s future were also coming to pass. In the league, a 1–1 draw away to Rochdale on the opening day of the season was followed by a first home defeat at the hands of Bournemouth. Two away games within the space of three days yielded a 1–0 win at Plymouth Argyle and a point in a 1–1 draw against Southport, only for the team to stutter again at home, losing to Charlton Athletic and Oldham Athletic, both by 2–1.

By the time September was out, Watford had also taken maximum points at the Goldstone under the old two-points-for-a-win system, abolished at the end of the 1980/81 season in favour of three for a victory. That left Saward’s men sitting twenty-first in a league table consisting of twenty-four clubs. Consecutive away games at the start of October brought relief in the shape of a 1–0 win versus Oldham followed by misery at Blackburn Rovers, Albion surrendering a 1–0 half-time lead to lose 3–1.

Then came Halifax Town at home: another defeat, this time by 1–0, making it five reverses out of five in the league at the Goldstone and six out of six in all competitions. At which point the levee containing any last drops of supporter goodwill towards Saward for his previous achievements finally broke.

If there was one thing football club chairmen hated more than losing back in the 1970s, it was falling attendances. In the days prior to mass advance season ticket sales and television deals ending in multiple zeros, clubs depended largely on whatever cash came through the turnstiles on match days for income. Having averaged a fairly respectable attendance figure of 14,188 over the course of the 1972/73 season, despite the dire results, Albion’s gates dropped alarmingly during the opening weeks of the 1973/74 campaign as defeat followed defeat. When only 6,228 bothered to turn up for the Halifax game on Saturday 13 October, Bamber’s patience finally ran out. Win or lose the following Saturday at home to fellow strugglers Shrewsbury Town, he decided that a board meeting should take place immediately afterwards with just one item on the agenda: the sacking of Pat Saward as manager.

In the intervening days between the Halifax and Shrewsbury matches, Saward carried the air of a dead man walking about him. Rather than acting as a rallying call, his column for the Wednesday edition of the local Evening Argus newspaper – headlined ‘I’m Staying to Pull the Club Back’ – read more like a suicide note. ‘A chance remark by a tradesman to my wife this week put Albion’s dilemma in a nutshell,’ Saward wrote.

He is a supporter and said quite simply ‘We don’t feel part of the club anymore.’ This man was one of the 30,000 who joined in praising the promotion side the night of the Rochdale match. Now, as he freely admitted, he is anti-everything at the Goldstone although he continues to watch matches. Once, and not very long ago, he enjoyed watching the Albion. He even went so far as saying that the time we went up he could have got down and kissed my feet. Now he wants to kick my backside and there must be many more like him. ‘I have the feeling now that everything has disintegrated and all that wonderful spirit has gone down the drain,’ he says. This is it exactly. We have lost that feeling of togetherness at the club. Unfortunately I feel we are going the other way and attracting failure.

If Saward had any inkling that Bamber was about to fire him, and wanted somehow to change his chairman’s mind, then as pleas in mitigation go there have been better.

As if in sympathy with Saward’s plight, the weather well and truly broke across Sussex towards the end of that third week in October. On the Friday, gale-force winds and mountainous waves caused a 75-ton barge to break loose and smash into Brighton’s Palace Pier, sending amusement kiosks, walkways and a helter-skelter tumbling into the sea. The following day, a paltry crowd of 5,308, Albion’s lowest home attendance of any description since 1963, paid to see Ronnie Howell and Ken Beamish score the goals that beat Shrewsbury 2–0. Saward wasn’t even there to witness it, the reason for his absence being a supposed scouting mission for players. Afterwards, as arranged, the club’s board convened to agree on the manager’s sacking. The only surprise, other than Albion managing to win a home game, was that news of his dismissal took until Tuesday 23 October to break, Saward himself being informed on the Monday.

‘This is a decision by the board who bore in mind that the most important thing is the club,’ said Bamber in justification. ‘I have just seen Pat Saward. He is very upset and very sick. I would also feel very sick, but we have had six home defeats and are down to crowds of 5,000 wonderful people. No club can live on such gates. The running of the team is the manager’s responsibility. I feel sorry for managers in a way, but if they want to be managers it is up to them. Naturally, some of the players are upset at him going, but I have just had a meeting with the players and morale is high.’

Bamber denied that the club had already lined up a successor, confirming the job would be advertised ‘to get a really top manager’. Money would also be available to buy players. ‘It is not easy to get them and we have been after a half-dozen this year without success,’ he added, conveniently sidestepping questions over where that money might come from and why, if funds existed, so little had been made available to Saward for team strengthening.

‘I still cannot believe it has happened, but I will say nothing to knock the club,’ the now ex-manager told a small huddle of journalists waiting outside the Goldstone. ‘The reason I have been sacked is that they say I can no longer motivate the players. What I need now is a holiday to get away from it all.’

‘Pat took his sacking really badly,’ recalls Brian Powney. ‘In fact, I don’t think he ever really got over it. Years later I was in London staying in a hotel on business. I came down in the morning and was having a cup of tea in the lounge with my work colleague before getting a taxi, and I heard this voice that I knew. And it was Pat Saward. He was being interviewed for a job. He was as chuffed to see me as I was to see him, but he didn’t get that job. It wasn’t for a league side. It was a non-league side. That upset me a bit. He seemed to fade away, which was a tremendous shame because he was better than that.’

‘We [the players] didn’t get consulted about Pat’s dismissal,’ adds Lammie Robertson. ‘Maybe one or two of the senior players did, I don’t know, but I certainly wasn’t asked. I’d been places where the directors or the chairman had meetings with you, sometimes one on one, to ask what you thought about things. And you know in the back of your mind what’s happening, that they’re thinking of maybe changing the manager. But nothing was discussed with me or anyone else as far as I’m aware. He just went.’

If there was a clue as to what lay ahead regarding the possible identity of Albion’s next manager, then it was Bamber’s fondness for mixing with celebrities. Property development may have been his forte, but there was always something of a frustrated entertainer lurking within Albion’s chairman, who, in the years immediately after the Second World War, had drummed semi-professionally with several jazz bands around the London area. His part-restaurant, part-nightclub in the village of Ringmer, twelve miles north-east of Brighton, attracted many of Britain’s top acts of the time, including the likes of Bruce Forsyth, Des O’Connor and Les Dawson. It being a relatively small venue with a limited capacity, Bamber would often reach into his own pocket to meet the large fees commanded by such celebrities. The Ringmer Restaurant, as it was called (later to become the 2001 Discotheque), wasn’t quite a vanity project, but it wasn’t far short.

‘The one thing I always found about Mike was he was a bit star-struck,’ says Brian Powney. ‘He liked being seen with celebrities, very much. And it would cost him money sometimes to have these people with him. Quite often if they were appearing at Ringmer then he’d get them down to watch a game. One time we were in the dressing room before kick-off and Mike comes in with the guy from Peters and Lee, who were a very successful act at the time. And he [Lennie Peters] was of course blind. So he’s sitting there and everybody’s looking at each other going, “What’s going on here?” We’re more politically correct now, but back then it seemed a bit bizarre. You’re about to play a football match and you’re all thinking, “How’s he going to see the game?” I remember [singer] Frankie Vaughan coming in once and he was like an excited schoolkid because it used to go in tandem: footballers liked showbiz people and showbiz people often wanted to be footballers. It used to criss-cross all the time. I met many, many celebrities while I was Brighton.’

Did Bamber really intend to advertise for a new manager, or was there somebody he had in mind all along to replace Saward? Only the chairman himself together with one other man could ever have answered that question. At the beginning of October came confirmation that Albion director Harry Bloom had been appointed as the club’s vice-chairman, in effect stepping up to plug the gap created by Len Stringer’s departure. It was Bloom who would act as Bamber’s confidant over the weeks, months and years ahead, fulfilling various important roles including that of intermediary between the ambitious chairman and his managers whenever team matters and boardroom politics threatened to overlap. Bloom would also play a pivotal role in the negotiations to land Albion’s next manager, helping guide Bamber through the minefield of having to deal with one of the quickest wits, not to mention brains, in the game.

Call it journalistic intuition, but Evening Argus sports writer John Vinicombe, who covered Albion throughout the 1970s right up until his retirement in 1994, had a hunch about who Bamber might try to persuade to take the manager’s job. It seemed almost too ridiculous to contemplate, let alone write, but that hunch needed to be aired in print despite the risk of public – not to mention professional – ridicule. ‘Could the club afford Brian you-know-who?’ he speculated on Thursday 25 October, one seemingly throwaway yet carefully calculated line aimed at drawing debate on what he already suspected.

More than a few people laughed at Vinicombe when that story hit the streets. Not that he cared. Within forty-eight hours, the Evening Argus man would have the scoop of his career.

3

IN THE BEGINNING

Long before the European Cups, league titles and other assorted silverware won by Brian Clough the manager, there was Brian Clough the player.

In the 1950s, two types of centre-forward ruled the British game. The first was the tall, strapping, bull-in-a-china-shop variety; men such as Bobby Smith of Tottenham Hotspur (and, later in his career, Brighton & Hove Albion), Bristol City’s John Atyeo and Nat Lofthouse of Bolton Wanderers who would run through brick walls to put the ball and, if necessary, the goalkeeper into the back of the net. The second kind relied more on subtlety and mobility, strikers who read the game in order to be in the right place at the right time to pass rather than bulldoze the ball into the goal. Clough – along with players such as Manchester United’s Tommy Taylor and Charlie Fleming of Sunderland – belonged in the latter category.

The record books vary slightly according to the source, but are startlingly impressive no matter what you choose to believe. In 222 appearances for Middlesbrough spanning 1955 to 1961, Clough scored either 204 or 207 goals in 222 appearances (Clough himself plumped for the former in his second autobiography). Following his transfer from Middlesbrough to Sunderland he went on to net an undisputed sixty-three goals in seventy-four games for the Wearsiders before being forced into premature retirement aged twenty-nine, the result of medial and cruciate ligament damage to his right knee sustained in a collision with Bury goalkeeper Chris Harker at Roker Park on Boxing Day 1962. Many a club suffered at the hands, or rather boot, of the prolific Clough whose outstanding form, albeit in the Second Division, was barely recognised at international level. ‘Two bloody caps’ was Clough’s own take on the derisory number of England appearances that came his way. However, it’s fair to say some clubs suffered more than others.

In April 1958, courtesy of crushing Watford 6–0 at the Goldstone Ground, Brighton & Hove Albion were promoted to the English Second Division for the first time in the club’s history. Their reward was a trip to Middlesbrough’s Ayresome Park ground on the opening day of the 1958/59 season, Saturday 23 August, to face a team stuck in something of a trough having been relegated from the First Division in 1954. Nevertheless, with the prolific Clough up front, Middlesbrough always posed a threat in front of goal. So it proved that day as Albion, with understudy Dave Hollins deputising for first-choice goalkeeper Eric Gill, were thrashed 9–0.

And Brian Clough scored five of them.

‘I kicked off nine times and I think I touched the ball more than anybody on our side,’ says former Albion striker John Shepherd of a result which, at the time of writing, remains Albion’s record defeat. ‘Cloughie got all those goals, I got five or six kicks to my legs, and I don’t think I even had a shot at goal. It was one of those games where you weren’t in it at all. Afterwards it was a bit like, “Flipping heck, what’s this all about? What have we let ourselves in for?” Everything went right for them and nothing went right for us but when someone singlehandedly scores five goals against you, then you know he can’t be bad.’

Four months later, Middlesbrough travelled to Sussex for the return fixture. The match proved to be an absolute cracker, Clough scoring a hat-trick as the visitors won 6–4, taking his season’s tally against the Second Division newcomers to eight. The following campaign he bagged another two when the sides met again at Ayresome Park, Middlesbrough triumphing 4–1, before Albion finally managed to exact some revenge with a 3–2 win at the Goldstone on St George’s Day 1960. No prizes for guessing who scored one of Middlesbrough’s consolation goals.

‘People remember him as a manager and of course his struggle with the demon ale during the last few years of his life, but they forget what a talented centre-forward he was – and he really was talented,’ says Adrian Thorne, himself no slouch in front of goal, scoring forty-four times in eighty-four appearances for Albion between 1958 and 1961. ‘He took us to the cleaners in those matches. I suppose having recently played in the Third Division we were used to competing against centre-forwards who would miss as many chances in front of goal as they took. He didn’t seem to miss, or at least miss the target. If it didn’t go in, then the goalkeeper usually had to make a save. I didn’t know him as a man, but what a tremendous player.’

As prolific a striker as he was, Clough was far from the most popular player in Middlesbrough’s dressing room. Despite failing his eleven-plus exams at Marton Grove School and being ranked fifth-choice centre-forward at Ayresome Park after joining the club on turning seventeen, the former ICI messenger boy – born at 11 Valley Road, Middlesbrough, on 21 March 1935 – wasn’t short in the confidence stakes. Clough’s self-belief came laced with a cocky arrogance, the kind that took older players to task for their failings on the field and younger ones for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time, as former Middlesbrough left-back Mick McNeil experienced in his very first encounter with the club’s star striker.

‘We [McNeil and goalkeeper Bob Appleby] used to go along in the evenings after work and train under the stand, in the sweat box, the “soot box” we called it because it was full of dust,’ McNeil recalled in Nobody Ever Says Thank You, Jonathan Wilson’s 2011 biography of Clough. ‘One evening Cloughie was there, playing table tennis with some first team player. We were just young lads doing our training. We were doing step-ups. The box had a wooden base and it moved when you tried to do these things as quickly as you could. So the floor was bouncing. I heard this voice: “Hey, Buster!” The first words Cloughie ever spoke to me. “Hey, Buster, do you mind? We’re trying to play table tennis.” Bobby and I said under our breaths, “And we’re trying to train”, but we sat on the seat and watched him finish his game, then we carried on.’

Clough’s directness extended, albeit with some justification, to certain members of Middlesbrough’s team, whose defensive naivety seemed to go way beyond the occasional lapse. In his second autobiography, Walking on Water, Clough asserted that ‘it doesn’t take a master mathematician to produce the theory that a team with a centre-forward as good as I was, scoring as many goals as I did, should have been promoted.’ And yet still Middlesbrough languished in the Second Division. Why? Because matches were, so he believed, being fixed.

‘I was suspicious,’ Clough continued. ‘I’d kept an eye on our defenders and to my mind something had to be wrong. Not even incompetence or crap players could explain the way Middlesbrough were letting in goals.’ Clough’s misgivings were understandable. Despite beating Brighton & Hove Albion 9–0 and 6–4 over the course of that 1958/59 season, Middlesbrough somehow conspired to finish below the Sussex club in the final league table (Albion coming twelfth, one place above Middlesbrough). Two of the players Clough most suspected of dirty dealing, Ken Thomson and Brian Phillips, were both later named in an investigation by the Sunday People as being involved in widespread match-fixing within the English game, receiving prison sentences and life bans from the sport.

Whether there was anything fishy going on at Middlesbrough circa 1958/59 has never been firmly established, but against such a backdrop Clough can almost be forgiven for cutting something of a brooding presence within the dressing room. ‘The injustice of it all at Middlesbrough, the good work I did that was so blatantly undone by others in the team, produced more than anger and resentment,’ he admitted of a period which had a profound effect on his managerial ethos of later years, namely that good teams are built from the back. ‘There’s no point in having the best and most prolific attack in the league if you can’t keep the ball out of the net at your end. The Middlesbrough episode taught me a fundamental footballing fact of life – defenders need to be as good at their jobs as any forward.’

Clough’s arrogance, aloofness and outspoken nature created individual enemies within the Middlesbrough squad, especially during the 1959/60 season, when manager Bob Dennison elected to make him captain (prompting a players’ revolt, Dennison holding firm against a round robin asking for Clough be stripped of the mantle). However, on a team level, Clough continued to be tolerated for the simple reason that he was very good at his job. ‘He [Clough] used to say, “I’m not wasting energy running out to the wings or chasing back,”’ former Middlesbrough winger Billy Day would recall. ‘That’s what you lot get paid for. He’d say, “My job is in the penalty area scoring goals and that’s what I get paid for.” And you wouldn’t argue because he was the one who got you your win bonus.’

In Clough’s defence, his levels of competiveness far outstripped those of many of his teammates content simply to plod along week after week in the Second Division, something likely to have further fuelled the ‘us’ and ‘him’ environment which almost inevitably arose at Ayresome Park. In the same way that Roy Keane, himself a graduate of Brian Clough’s managerial style at Nottingham Forest, railed against anyone whose appetite for the game (and in particular winning) failed to match his own, Clough strived to try harder all the time in order to improve and be successful. Otherwise what was the point?

That’s a question Middlesbrough goalkeeper Peter Taylor had been contemplating after losing his first-team place in 1960, some five years after signing from Coventry City. Taylor was Clough’s one true friend on the playing staff at Middlesbrough, someone who immediately identified his talents as a striker. However, whereas Taylor openly championed Clough as potentially the greatest goal-scorer in England, he himself was already eyeing a different career path within football, having grown wise to his own limitations as a keeper. While at Coventry, Taylor had served under Harry Storer, a member of the new breed of post-war managers who lived, breathed and slept the game rather than treating it as a pre-dinner inconvenience. Storer loved nothing more than embarking on scouting missions, which often yielded unsung yet capable players who cost little or nothing. That type of coaching position, Taylor decided, was where his future lay.

In 1961, Taylor left Middlesbrough for Port Vale before transferring again in May 1962, this time to non-league Burton Albion. Seven months later, he became their manager, embarking down the road – so Taylor hoped – to becoming another Harry Storer. Clough, bereft of his closest ally at Middlesbrough, departed Ayresome Park soon afterwards for Sunderland, where he continued terrifying defenders until that fateful afternoon in December 1962 when, in the process of chasing a slightly overhit through ball on a heavy pitch, his right knee made contact with Chris Harker’s shoulder. Hitting the ground hard, Clough blacked out briefly before attempting to climb to his feet. Unable to stand, he was carried from the field and taken from Roker Park to Sunderland General Hospital, his career all but over.

It was almost two years before Clough bowed to the inevitable. The first attempted comeback, late in 1963, came to nothing, causing news of his supposed retirement to make headlines in the local Football Echo. By August 1964, Clough was training again, graduating to the reserves and then the first team where he made three appearances in the First Division, scoring one goal against Leeds United. Alas, it was to be a false dawn. Shorn of his speed and limping through matches, Clough’s playing career had come to an end, leaving him feeling vulnerable, angry and uncertain about his future.

‘I went berserk for a time,’ Clough would confess of the period around his retirement. He drank alcohol, heavily. He lashed out at his teammates, including Len Ashurst, the full-back who had delivered the overhit pass in the build-up to the injury, appearing to blame him for the incident. He castigated the coaching staff, directors and seemingly anyone unfortunate enough to cross his path. Eventually George Hardwick, who had recently replaced Alan Brown as Sunderland’s manager, decided enough was enough. Rather than have him moping around Roker Park, Hardwick asked his ailing striker to start working with the youth team players every afternoon. Brian Clough the manager had arrived.

‘Thanks to George Hardwick’s generosity – and it was generous because neither he nor I knew whether I could coach – I was given a head start on others my age,’ Clough remarked of his lucky break, albeit amid unfortunate circumstances. ‘I was able to take the first tentative steps on the road to a managerial career five years ahead of schedule.’ Although he would never fully recover mentally from the blow of having to retire so early from playing, Clough soon realised that he was indeed cut out for management. Still young and skilful enough to impress on the training field, his verbal dexterity also proved inspirational, especially when it came to convincing teenagers that they were better players than they perhaps were. He sat a Football Association coaching exam, guided Sunderland into the semi-finals of the FA Youth Cup and as a consequence became Sunderland’s official youth team manager. There was something else as well, a confession he almost apologetically acknowledged in Walking on Water: ‘The truth was that I’d developed an instant liking for being in charge.’

For all his achievements during those few months spent coaching the kids, by the summer of 1965 Clough was out of work. When Hardwick was controversially sacked despite comfortably keeping Sunderland in the First Division, Clough found himself exposed to hostile fire from the directors, who hadn’t forgiven him for his volatile behaviour while injured. Sure enough, his marching orders followed a few days after Hardwick’s dismissal. It left a sour taste in the mouth, especially as the club pocketed virtually all of the £40,000 insurance pay-out on his knee injury; Clough received just £1,500 plus the proceeds from a testimonial arranged by Hardwick attended by 31,000 appreciative Sunderland fans. His mistrust of directors and dislike of football politics, a seam that would run throughout Clough’s managerial career, was duly cast.