Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

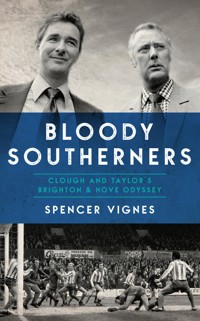

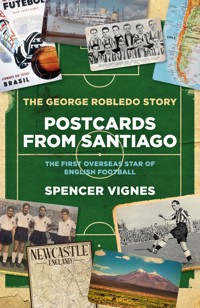

Long before Erling Haaland, Thierry Henry and Eric Cantona, there was George Robledo, the first overseas star of English football. Abandoned by his father as a child in Chile, Robledo came to the UK, where he was raised in a Yorkshire mining village, serving underground as a 'Bevin Boy' during the Second World War prior to making his name with Barnsley. During the 1951–52 season, his thirty-three goals for Newcastle United in what is now the Premier League were the most goals scored in a single season by an overseas registered, foreign-born player, a record that has stood unbroken for over seventy years – despite what the record books might say. Postcards from Santiago is the poignant, inspiring story of Robledo's remarkable journey from the moon-like wastes of the Atacama Desert to the cover of John Lennon's 1974 album Walls and Bridges, via Wembley glory and the 1950 World Cup in Brazil. Where, in England's first ever World Cup match, Robledo became the first Football League player from outside the British Isles to face England in an official international. Featuring interviews with family, friends and admirers, this fascinating biography is the definitive account of a man who overcame immense hardship and heartache to become a sporting trailblazer in his adopted homeland and a national hero in his native Chile.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 427

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iiiiii

ivIn memory of Mary Appleton, my maternal grandmother, and Mr Tibbs, so much more than just a feline companion over the past fifteen years of my writing life. v

vi‘To travel is to live.’

Hans Christian Andersenvii

Contents

Author’s Note

Several of those who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this book consider English to be their second language. Rather than reworking or ‘polishing’ quotes so the sentence construction seems less Spanish and more English, their words have been left pretty much as said. If someone’s speech pattern appears a little unorthodox or quirky, then that’s probably why.

Prior to 1992, the four main professional football leagues in England and Wales were known as the First Division, Second Division, Third Division and Fourth Division. The First Division is now the Premier League, the Second Division is currently the Championship, the Third Division is League One, and the Fourth Division is League Two. xii

Introduction

It was a question that had everyone in the room stumped almost to the point of silence.

‘Who holds the record for the most league goals scored by an overseas player in the top flight of English football in a single season?’

I felt as if I should know the answer, having written about sport for the vast majority of my adult life. But I didn’t. There I was, appearing as a guest at the Brighton branch of Sporting Memories, a UK charity which encourages older people to meet and reminisce through talking about sport, and I’d seemingly been exposed as a total fraud.

A few educated guesses had been made initially by the twenty or so members who’d gathered to hear me talk about my latest book before getting down to the far more serious business of their weekly Monday morning quiz.

Thierry Henry?

Cristiano Ronaldo?

Jürgen Klinsmann? xiv

What about Dennis Bergkamp? Or Luis Suárez?

One by one, our quizmaster, the former England rugby union international, cricketer and BBC broadcaster Alastair Hignell, batted away each incorrect answer, including my own shot at restoring some professional pride (Mohamed Salah, just in case you were wondering).

Gradually, the suggestions became little more than shots in the dark. Robin van Persie? Gianfranco Zola? Osvaldo Ardiles? Not Ricky Villa, surely? Robert Pires? Until, in David Ginola’s wake, the well of potential candidates ran dry and an air of befuddlement fell across the group.

Maybe it was the presence of the former Wales and Newcastle United goalkeeper Dave Hollins in the room that did it, but out of the blue, someone came up with a name, the correct name at that – George Robledo.

George Robledo! Yes, YES!

…and it all came flooding back.

Some twenty or so years previously, I’d covered a Newcastle United game at St James’ Park during the managerial reign of Bobby Robson, often cited as one of the nicest guys to walk the Earth, let alone work in football. The post-match press conference had ended, but Robson continued talking to some of us hacks who weren’t on a deadline about his heroes, the ones he’d watched playing for Newcastle while growing up in north-east England in the years immediately after the Second World War. He mentioned Jackie Milburn – I knew about him. He mentioned Joe Harvey – I knew about him too. He mentioned Bobby Mitchell – I’d sort of heard of him. But then xvRobson said another name, which meant absolutely nothing to me. That name was George Robledo.

Clocking a couple of blank expressions in our midst, Robson gave us George Robledo in a nutshell. I wasn’t taking notes, just listening intently, but this much I do recall – he’d come as a boy from Chile to Yorkshire, worked as a miner prior to becoming a professional footballer (Robson had also served underground as a trainee electrician at a colliery in County Durham) and scored lots of goals for several clubs. I also recollect Robson saying he saw plenty of George Robledo in Alan Shearer. Praise indeed, as anyone who might remember Alan Shearer in his 1990s pomp would acknowledge.

On the long drive back home, I thought a lot about George. Here was someone who scored thirty-three league goals for Newcastle United in the First Division (or the Premier League in today’s money) during the 1951–52 Football League season. No other overseas registered, foreign-born player had reached that number before and no other overseas registered, foreign-born player has reached that number since (although as I write, Mohamed Salah of Liverpool is indeed doing his level best to change that). At the time of my visit to Brighton (January 2023), Manchester City’s Norwegian international striker Erling Haaland was on course to break George’s record, a feat Planet Football has since decreed he achieved. But then, as one extremely clued-up member of that Sporting Memories group had pointed out, Haaland was actually born in Leeds. As in Leeds, England, where his father once played football. Going by the rules of geography, George is, as I write, still the record holder. Splitting hairs? Maybe, maybe not. It all depends how accurate or perhaps pedantic you want to be. xvi

Either way, there were two undeniable truths about George Robledo. One, he’d clearly been a phenomenal football player. And two, his remarkable achievements seemed to have been almost completely forgotten about in his adopted country. Over the course of writing and researching this book, I’ve learned a little about how this has been allowed to happen.

The British Isles (and as a sports writer, this is something of a bugbear of mine) has morphed into the undisputed global leader for airbrushing large chunks of its football history from the public consciousness. If it occurred before 1992, when football was rebranded rather than reinvented with the arrival of the English Premier League, then it’s almost as if it never happened. Forget about Stanley Matthews. Forget about Tom Finney and John Charles. Forget about Nat Lofthouse, Jimmy Greaves and Denis Law. Forget ’em all, because they played a long time ago when the world was black and white and their achievements don’t really count anymore – or so the brainwashers would have you think. This doesn’t happen in Italy. It doesn’t happen in Spain. It doesn’t happen in Brazil, Argentina or any of the game’s other traditional bastions. It doesn’t happen in George’s native Chile. And yet, when it comes to the British Isles (and I say the British Isles as the gravitational pull of England’s top football clubs has long been particularly felt in Ireland and Wales), the delete button has been pushed on huge swathes of what went before, burying the treasure instead of celebrating and preserving it.

On reaching Cardiff, I fired up my laptop to see if a book had ever been written about George, partly because I wanted to read one and partly (the greater part, admittedly) because I’d felt a sudden calling and fancied having a go myself. xvii

No such book existed.

So I went for it, blind at that stage to what exactly I was taking on but determined to unearth the treasure that was, and indeed remains, George Robledo. The catch about unearthing something long hidden is that besides all the ‘wonderful things’, as Howard Carter described the contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb on first sight, you can also chance upon plenty of heartache. And so it would prove with George. To paraphrase Gordon Sumner, aka Sting, born a modest walk from St James’ Park when George was at his zenith as a player, love can mend lives, but it can also break hearts.

Then again, George Robledo’s generation were masters in the art of triumphing over adversity. Which, from where I’m sitting, is another reason why the British Isles should strive to be more Italian, more Spanish, more Brazilian, more Argentinean and more Chilean in terms of remembering those footballing greats once familiar to millions. It’s not as if they haven’t got astonishing stories to tell, even if they do come at you from beyond the grave.

SpencerVignesCardiff,WalesMarch2025xviii

1

All Those Years Ago

‘Weshallgoontotheend.’

– Winston Churchill

George Robledo saw the ball coming late, almost too late to do anything about it. Under normal circumstances, he would draw his head back before bringing it forward sharply to meet the heavy brown leather orb, much as a cobra attacks its prey. Doing it that way, he found, put more pace on the ball, and more pace on the ball meant the goalkeeper was less likely to react in time to make a save.

But these weren’t exactly normal circumstances.

Six minutes remained in the 1952 FA Cup final, the last six minutes of what had been a long, demanding season, consisting of forty-two league games and half-a-dozen FA Cup fixtures. In the league George had notched thirty-three goals for Newcastle United, topping the First Division scoring charts in the process. Another five had followed in the FA Cup, taking his overall tally for the campaign to a thumping thirty-eight. 2

Now, in game seven of Newcastle’s FA Cup run, beneath the twin towers of Wembley Stadium, with Winston Churchill – theWinston Churchill – on hand to present the trophy to the winning team, George was feeling tired and frustrated. Of all the opportunities that had presented themselves in his dreams to score goal number thirty-nine, only one had materialised in reality (and he’d blasted that high over Arsenal’s crossbar just after half-time). Usually George would be confident that, even at this late stage, one more chance would present itself. Today, he wasn’t so sure. Even if it did, would ‘Pancho’, as his teammates called George on account of his Chilean heritage, have the required stamina and composure to break the stalemate and score the winner?

Bobby Mitchell, Newcastle’s mesmeric left-winger, reckoned he knew the answer. Tall, thin and blessed with a deceptively lazy stride that fooled many an opponent, the Glaswegian was determined to set George up with that one last chance. Sure, Mitchell could see his teammate was flagging mentally as well as physically. All the more reason to plant the ball right on George’s head so he barely had to move for it.

As Arsenal’s defenders closed in, Mitchell steadied himself before crossing towards the far post, where George, during a conversation in the dressing room at half-time, had told him he would be waiting should such a scenario present itself.

And he was.

That was the good news. The not so good news was the ball came towards George at speed through a crowded penalty area. With little time to react, he instinctively let it glance off his brow towards the near post, the one place he knew George Swindin in the Arsenal 3goal might struggle to cover. At which point, the entire stadium and everyone inside it – the players, the spectators, the officials, the press men, the photographers around the touchline, even old Winston himself – seemed to freeze. Or at least they did to George. It was as if, he would recall many years later, Wembley Stadium was a record player and some giant hand had reached down and lifted the needle, cutting the sound as well as the action in an instant.

Would the ball end up in the net to register the only goal of the game?

Would Swindin scramble across in time to make the save?

Would the ball hit the post and come back into play or go out for a goal kick to Arsenal?

…or would he faint right there and then through sheer exhaustion before discovering the answer to any of the above (more than a possibility, so his ailing body told him)?

All of this was being played out in mere seconds, which, to George, felt like an eternity.

When the giant hand eventually returned the needle to the record, it came accompanied by a roar from the Newcastle supporters among the 100,000-strong crowd. George’s header had struck the inside of Swindin’s left-hand post on its way into the back of Arsenal’s net. For the second year running, Newcastle United had won the FA Cup and Tyneside was going to party like it was 1945. As were parts of Yorkshire, Chile and just about anywhere else connected to the Robledo family and their remarkable story.

He considered himself to be a calm, rational soul, did George. War tends to shape you that way, as does a depression, post-war frugality and thirteen months working down a coal mine. The perfect recipe, without a doubt, for a grounded personality. 4

And yet scoring the winner in an FA Cup final can do funny things to a person.

Did George celebrate his goal by careering around the field like a speedboat without a driver, despite his aching limbs? Yes, he did. Did he jump partially clothed into the swimming pool at the team hotel later that evening? That would also be a yes. Did he amble up and down the corridors of the train carrying the team back to Newcastle, singing songs and handing out cigarettes to strangers? Yes, yes, he did that as well. All totally out of character. But then how often does a player get to score more league goals in a single season than anybody else andthe winner in a cup final? If you can’t let your hair down then (and George did indeed have a lovely head of jet-black hair to go with his film star looks), when can you?

He knew what this would all mean, of course. For more than three years, ever since George had started scoring goals for Newcastle United and especially since starring for Chile in the 1950 World Cup, the lucrative offers to go and play abroad – where footballers weren’t constrained by a maximum wage and could virtually name their price – had flooded in. Now there would, inevitably, be more. It was a nice problem to have and George certainly wasn’t complaining. Except that moving overseas would involve uprooting the whole Robledo family – himself, his mother and his two brothers – yet again. Wherever one went, the others followed. That was the rule. All for one and one for all. George loved Newcastle and its people, just as he’d loved Yorkshire on arriving in England from Chile as a child. Leaving certainly wouldn’t be easy. On the flip side, going abroad equalled financial security. The itch he’d developed to travel and experience different cultures would get scratched. 5As long as he kept scoring goals for Newcastle, the dilemma over whether or not to leave England wasn’t about to go away.

Right now, however, George resolved to live life in the moment and enjoy himself for a few precious days. He had an FA Cup winner’s medal in his back pocket, as did his brother Ted, a fellow member of Newcastle’s victorious Wembley team. The fact they’d shared in the experience, having literally come so far together in their relatively young lives, made it all the more special for the pair of them. Ted had even played a part in the winning goal by passing the ball to Bobby Mitchell, stationed on United’s left flank.

Part of living in the moment involved returning to the pile of newspapers that his mother had bought after the final. You know, just to make sure Swindin hadn’t in fact saved his header. In particular, George found himself drawn to a black and white photograph that captured the exact point in time when the needle had returned to the record. There was teammate Jackie Milburn on the right, with his back to the camera. There was George tussling with Arsenal defender Lionel Smith, both men looking towards the goal, one in hope, the other in despair. And there, oh joy of joys, was the ball on its way over the line, the beaten Swindin helplessly observing its passage.

‘As the press cameras caught it!’ screamed the headline on page six of TheJournal, Newcastle upon Tyne’s daily newspaper. ‘George Robledo has done the damage. The ball, headed in, has just struck the inside of the Arsenal goalpost and is on its way into and across the goal.’

TheJournalwasn’t the only newspaper which featured the photograph. Most of the UK nationals carried it, as indeed did many of 6the other big regional titles such as the BirminghamPostand LiverpoolEcho, which, like TheJournal, doubled up as national papers, bringing important domestic and world news to the doorsteps of local readers.

And so it came to pass that the photograph was spotted by an eleven-year-old pupil at Dovedale Road Primary School in Liverpool called John Lennon. So taken with the photograph was Lennon, despite not really liking football, that he painted a picture of it. The only difference, besides the addition of some colour to Wembley’s turf and the players’ kits, was the ball hadn’t yet crossed Arsenal’s goal line in Lennon’s picture. Instead, it hung tantalisingly in mid-air, with Swindin seemingly poised to make the save. At the top he’d scribbled ‘John Lennon, June 1952, AGE 11’, accompanied at the bottom by just one word – ‘football’.

In the years that followed, John Lennon would become one of the twentieth century’s most celebrated songwriters, both as one-quarter of a certain rock and pop combo called the Beatles and a solo artist. When the time came to choose the artwork for his 1974 album WallsandBridges, Lennon reached for a selection of paintings and drawings dating back to his final term at Dovedale Road. Among them was his recreation of George Robledo’s winning goal in the 1952 FA Cup final, which ended up being reproduced on the front cover.

George had felt tired. He’d felt frustrated. It had, up to the point when he scored the winning goal, been George’s worst performance of the entire 1951–52 season. John Lennon didn’t know any of that. The eleven-year-old future Beatle simply recognised the photograph for what it was – a knockout action shot of a football player 7scoring a goal. A football player who, ironically, had taken his first steps on British soil in Lennon’s home city of Liverpool. A football player who, like Lennon, lacked a father figure. A football player raised by a strong, independent, uncompromising matriarch, also like Lennon.

‘The worst pain is that of not being wanted, of realising your parents do not need you in the way you need them,’ Lennon would declare in a 1971 interview. George Robledo knew that pain. It was, in part, what spurred him on to such greatness in his chosen sport. But then he also had Elsie Robledo, his mother, to fall back on. Those record-breaking thirty-three goals in the league during the 1951–52 campaign, plus the six in the FA Cup, belonged as much to her as they did to him.

Little could George have imagined that his record, the one for the most league goals scored by an overseas player in the top flight of English football in a single season, would stand for such an extraordinarily long time. 8

2

Tomorrow Never Knows

‘Fear is petrol.’

– Judi Dench

She weighed almost 18,000 tonnes, measured 551 feet in length and spent the vast majority of her working life ploughing backwards and forwards between her home port of Liverpool and Valparaíso in Chile. That was the MV ReinadelPacifico, Spanish for ‘Queen of the Pacific’, launched in Belfast in 1931 and regarded as something of a jinx by those who served aboard her. There was the time when she ran aground on a sandbank off Bermuda with over 400 passengers on board, remaining beached for three days until being successfully refloated. There was the time a crankcase in her engine room exploded during trials in the Irish Sea, killing twenty-eight crew members and technical staff employed by her owners, the Pacific Steam Navigation Company. Perhaps most famous of all, there was the time when former UK Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald died on board as she made her way across the Atlantic Ocean. The old man’s health had been failing and he’d been greatly 10affected by the recent death of King George V, who he counted as a good friend. A holiday in South America, it was felt, would do him wonders. The Reinaand her dark reputation soon put the kibosh on that.

Then there were the multitude of other less newsworthy dramas that play out when you throw hundreds of people together at sea for days or even weeks on end – such as the one that befell Elsie Robledo and her three sons one March morning in 1932.

Born in the terraced house that was 3 York Street, West Melton, Yorkshire, on 27 October 1895, Elsie Oliver – as she started out in life – had not long turned twenty-three when she took up a job in Argentina as personal assistant to the wife of George Ellis, a well-to-do chemical engineer employed in the mining industry. In 1924, Mr and Mrs Ellis relocated to Oficina Alianza in Chile, a rough and ready outpost in the Atacama Desert renowned for its large deposits of sodium nitrate (sometimes known as Chile saltpetre), used in the production of explosives and fertiliser as well as preserving meat. Elsie went with them, and it was in Oficina Alianza that she met Arístides Robledo, the twinkly eyed company accountant at the mine where Ellis worked.

Arístides and Elsie married, settled down and had three children. There was George, born on 14 April 1926. There was Edward, better known as Ted, born on 26 July 1928. Then there was Walter, born on 8 December 1931, by which time Mr and Mrs Ellis were on the point of cashing in their chips and returning to the UK. A military coup led by General Luis Altamirano had tipped Chile into a period of political instability, with no fewer than ten governments holding power between 1924 and 1932. Throw in the effects of the Great 11Depression, along with the bell beginning to toll on Chile’s saltpetre mining industry, and the ties that once bound the couple to South America were fraying.

And so George Ellis booked passage on the ReinadelPacificofor all five of the Robledos. Elsie’s South American odyssey was at an end. Though both her parents had died since she’d left West Melton, returning to the relative security of Yorkshire, with its familiar faces and steadier employment prospects, made perfect sense. When the day came, the Robledos made their way to Iquique to meet the ship, bound for Liverpool, on its first scheduled stop out of Valparaíso. Up the gangway on the port side they went, at which point the Reinastarted casting its witchy spells.

‘They were there with their bags, ready to depart, at which point my grandfather, Arístides, said he was going back to buy cigarettes for the journey,’ says Elizabeth Robledo, the only child of George Robledo.

And he never returned. Everyone was looking for him all over the boat. It even waited long past its departure time while the search went on. In the end they couldn’t hold it any longer, so they pulled up the gangway and the boat left without him, but with my father and the rest of his family on board.

Why did Arístides do it? That, in the Robledo family, was always the million-dollar question. Maybe he couldn’t face the prospect of leaving his homeland? Maybe his marriage to Elsie was disintegrating? Perhaps, as his youngest son Walter always suspected, Arístides was having an affair and abandoned ship to be with his secret love? 12‘Anything is possible,’ says Elizabeth Robledo.

What we do know is that he vanished. Apparently, he turned up in his home city months later. They say he was very, very embarrassed about what he had done and that he just couldn’t leave his relatives behind in Chile. But who knows what else was going on with him? I don’t know and I’m not sure whether my father ever did either. He never talked to me about what happened that day. I heard it mentioned in conversations, but they were never very long conversations because I don’t think there was much to talk about.

At six years old, a child can show empathy, tell right from wrong and distinguish between fantasy and reality. Touch wood, they will have learned to count on the unconditional love and support of both parents. Despite the importance of school, family will still be the overriding influence on their development. Walter Robledo was only three months old when the Reinaset sail from Chile without his father on board. Ted was three years old. George, however, was just one month shy of his sixth birthday. He might not have understood the reasons why his father had suddenly walked out of their lives, but he would have known that’s exactly what he’d done. Without any explanation, without any goodbye, without so much as a backwards glance.

Antofagasta. Callao. Mollendo. Paita. Balboa. Cristóbal. Kingston. Havana. Bermuda. Vigo. A Coruña. Santander. One by one, the Reina ticked off its various ports of call en route from a Chilean autumn to a European spring, twenty-four days at sea in no-frills, 13third-class accommodation. Twenty-four days for a young boy to keep himself occupied, having explored every deck, corridor and lounge within hours of leaving Iquique.

Twenty-four days for a young boy to think, ‘What happened back there?’

Finally, on Saturday 2 April 1932, Liverpool loomed out of the haze, with its bustling quaysides and scuttling Mersey ferries. Back down the Reina’s stairs went the Robledos, minus Arístides, to be processed by customs and immigration before embarking on the final leg of their mammoth journey, this time by train through the Pennine hills to Elsie’s native Yorkshire. What questions she must have faced on setting foot in West Melton for the first time in fourteen years can only be imagined. Elsie, though, was made of stern stuff (‘formidable’ appears to be the word most commonly used to describe her). We know not, all these years later, whether she ever expected or indeed wanted to see Arístides again. What we can say is that the Elsie Robledo who arrived in West Melton in 1932 was determined to make a fresh start for her children as much as herself. An estimated 9 million people left Liverpool during its heyday as a port to pursue new beginnings in the New World. Mrs Robledo and her three sons bucked the trend by sailing the other way, yet her desire to create a new life for them in her old world burned just as fiercely.

Soon after arriving, the Robledos moved into 97 Barnsley Road, West Melton, living above a corner shop which had, up until then, been run by one of her uncles. The shop was called Oliver’s and it was known for selling hardware and timber, but Elsie turned it into a general store providing all and sundry. 14

As for George, he started attending the nearby Brampton Ellis Infant School before graduating to Brampton Ellis Juniors. Despite his reserved nature, making friends came relatively easy. It helped that English was his first language, courtesy of Elsie. Communicating with other children was not a problem. But he also excelled at ball games, particularly football and tennis. For any child or young person parachuted into a new environment, sport can be a great leveller. Being good at it gets you popular quickly. The fact that George was modest and not at all big-headed about his talents made him even more appealing to his classmates, girls as well as boys.

The hand that life had dealt him meant George grew up fast during those early weeks, months and indeed years in West Melton. ‘I look at pictures of him at that time and he seems very mature compared to the other boys his age,’ says Elizabeth Robledo.

That’s because he assumed the responsibility of being a dad for his two brothers. He took over the role of being their father. I don’t know how it affected him. He just did it, without ever saying anything bad about my grandfather. He probably suffered on the inside, and there would have been things he had to sacrifice to be there for his brothers, but he never expressed any regret about it. He loved his mother, he loved his two brothers and he was always looking after them. That never changed, even when he became a man. He was also very lucky because of the school he went to. The values he learned at Brampton Ellis – be brave, be strong, be polite, be honest, be humble – helped him deal with the situation he found himself in. He grew up quickly, but those values meant he grew up to be a wonderful person. He, and our family, have so 15much to thank that school for that it makes me cry just thinking about it.

In a working-class area dominated by coal mining and without a man’s salary to support the family, money could often be tight in the Robledo home, despite Elsie’s best efforts behind the counter and the support of relatives. David Kitchen, born and raised in the area around West Melton, recalls the time his grandfather, Lawrence Kitchen, first spotted the young George Robledo playing football on a piece of common land. He was good, anybody could see that, but what really caught Lawrence Kitchen’s eye was that George wasn’t wearing football boots. ‘People were poor then,’ says David Kitchen.

As the old saying goes, folk left their doors open because they had nothing to steal. George was playing in an old pair of shoes because he had no boots. So, my grandfather went and bought him a pair. I’m pretty sure they were only second-hand, but at least he now had some boots. I think they were the first football boots George ever had.

How poor were the people of West Melton and the surrounding towns and villages of the Dearne Valley in the 1930s? Among the poorest, if not the poorest, in the UK is the simple answer. The majority of households lacked a fixed bath. One in four people had access to their own toilet. Barnsley, situated five miles to the north-west, suffered the highest infant mortality rate in Britain. The mines kept the local (not to mention the national) economy going, but with them came the ever-present spectre of pit disasters and 16industrial diseases brought on by exposure to coal dust. The arrival of hire purchasing towards the end of the decade brought prosperity for some. However, for the majority, a combination of squalor, misery, darkness and filth prevailed.

‘The fathers worked the pits. The mothers held down domestic jobs and also brought up the children. And the children became a reflection of their parents. Some fathers would gamble too much or drink too much, and the children would suffer.’ So wrote the former Sheffield United, Sunderland and Leeds outside-left Colin Grainger, born in nearby Havercroft and seven years George’s junior, in his autobiography TheSingingWinger. In reality, the qualities that existed in the mining communities of Yorkshire tended to transcend the often grim realities of life. The spirit of the people and their resolve was immeasurable. Folk really did look out for each other, something that proved invaluable in times of war and industrial dispute. For all its ills, there were worse places to spend your formative years. George Robledo eventually left West Melton, but West Melton and what it stood for never really left him.

And in football circles, he was far from alone in that department. Tommy Taylor. David Pegg. Kevin Keegan. David Seaman. Ron Flowers. Joe Harvey. Alan Sunderland. Karen Walker. Mick McCarthy. John Stones. The list of footballers, some better known than others, raised in or around George and Ted’s adopted corner of Yorkshire is both long and impressive. The vast majority, once they’d gone out into the world, spoke warmly of the values instilled in them at a young age by their communities. They might not necessarily have wanted to move back in a hurry, but they remembered those places fondly. And that feeling was, by and large, reciprocated. 17

‘The one thing they celebrate in the Dearne Valley and many of the smaller communities across South Yorkshire is when their local heroes go on to do great things,’ says journalist Ashley Ball of the Barnsley Chronicle.

That was certainly the case when I was growing up in the 1990s, when you would still hear talk of the Robledo brothers and what they had achieved. It’s a bit more tribal now in terms of which team you support. But to me, it doesn’t matter if someone turns out for Sheffield Wednesday, Sheffield United, Barnsley, Manchester City or whoever – if they’re local, then I’ll celebrate that. And it doesn’t matter in what sport either. We’ve produced talented rugby players and cyclists, but historically, what our region has really excelled in is footballers and boxers. To see them doing well brings joy to what is a tough area. George had a tough upbringing and people still have tough upbringings now. There’s not a lot of money around in the Dearne Valley. There never has been. The way we can level the playing field and do our bit is in sport. That’s where we can get our joy.

‘If my memories appear to be those of somebody observing his past through rose-tinted spectacles, consider how many great and good footballers in post-war Britain emerged from mining communities,’ continued Colin Grainger in his autobiography.

Our world was a football training ground, an academy, and although not everybody came out of the experience having flourished, those austere streets were a space in which enchantment 18became possible. We did not even need a football. A tennis ball would do. And, of course, four coats for goalposts. At virtually no cost, we had a game that could occupy and stimulate every boy in the village, week in week out, throughout our adolescence.

Through his own adolescence, George created goals and he scored goals – 129 of them in four seasons for Brampton Ellis Senior School, to be exact. This included four against Thurnscoe Hill in the final of the 1938–39 Totty Cup, a competition for schools in the Don and Dearne areas of Yorkshire.

‘George was always remembered as being a head above everyone else in the school team, not in stature but in skill,’ says the renowned British music and sports writer Richard Williams, whose grandfather, Harold Steer, was headmaster at Brampton Ellis Senior School during the period when all three of the Robledo boys were pupils.

Of course, Ted also made a living from the game, but he was always more of a journeyman player, whereas George was the genuine article. He was an outstanding figure, he really was, and it was no surprise that he went on to achieve what he did. Funnily enough, my grandfather used to say young Walter would have been the best footballer out of the three of them had he not worn spectacles, but Walter always pooh-poohed that idea and said it was nonsense. Either way, they clearly made a formidable trio.

‘Back in 1973 or 1974, when I was about eight years old, one of the teachers asked me to help carry a few boxes upstairs to a store room,’ 19says former Brampton Ellis pupil David Wood, now Barnsley FC’s official club historian, who grew up in West Melton.

I distinctly remember him unlocking the door and indicating where the boxes should go, and I noticed that the room was full of old pictures from years gone by. One was of a school production with pupils dressed in what seemed to be Robin Hood attire. And there, in the middle of them all, was a picture of a football team proudly displaying their newly won trophies. Straight away, my eyes went to the boy sat front and centre – George Robledo. Before I could say anything, the teacher chimed up: ‘There will never be a school team to match those boys.’ There is something about the way George looks in that picture which sets him apart. He looks older, more mature. He’d travelled outside Yorkshire for a start, which the other kids in the photograph probably wouldn’t have done. Besides, perhaps, from going on holiday to Blackpool. He’d seen things that the others hadn’t.

In all likelihood, George would have created and scored plenty more goals at schoolboy level had he been living in normal times. At the start of his final year of formal mainstream education, 1939–40, the uneasy peace that had existed across most of Europe for some considerable time was finally broken. In the early hours of Monday 4 September, barely a day after the UK had declared war on Germany following the latter’s invasion of Poland, the air raid sirens rang out in anger for the first time across the Dearne Valley. It proved to be a false alarm – the aeroplane buzzing around was, in fact, an Allied 20one – but the tone was set. After months of rumour, speculation, public awareness campaigns and trial blackouts, everybody’s worst fears had been realised.

Despite their mining heritage, the Dearne Valley and the surrounding areas were not considered to be an immediate or highrisk target during the Second World War. And so it proved, as Germany, in the wake of the eight-month ‘phoney war’ that marked the start of hostilities, focused its wrath mainly on Yorkshire’s major industrial cities and conurbations, with Sheffield and Hull suffering devastating attacks in December 1940 and May 1941 respectively.

Nevertheless, the Dearne Valley was most certainly affected by the war as, for the second time in twenty-five years, a significant proportion of the area’s young men took up arms. Many of them would never return, with several local footballers listed among the dead, including former Barnsley forward Fred Fisher, killed in July 1944 when his Lancaster bomber was shot down over France while on a bombing raid to Stuttgart.

For the Robledo family, the war could potentially have ripped the carpet from under their existence only a matter of years after arriving in England. ‘Foreigners’ or indeed anyone with what appeared to be an exotic surname were often subjected to suspicion, tipping into outright hostility or even internment, something Italian communities across the UK discovered after Italy chose to nail its colours to Germany’s mast. Fortunately, Elsie’s local roots cushioned the family from any animosity that they might otherwise have experienced. It helped as well that George and the more outgoing Ted were popular sporty figures who, if push came to shove, could look 21after themselves. Fortunately, the need to watch one another’s backs in wartime never materialised.

On leaving Brampton Ellis Senior School aged fourteen in 1940, fresh from scoring another five goals in the final of that year’s Totty Cup (a 2–2 draw against Bolton Modern followed by a 4–0 win in the replay), George started attending Barnsley Mining and Technical College, with a view to getting a trade under his belt. That, pretty much up until the arrival of the Premier League and its riches in the 1990s, was the way it went for the majority of budding footballers, just in case the playing career fell through or to have something to fall back on in later life. Making a living from the game was always George’s holy grail, but the uncertainty brought on by war added an extra dimension to keeping one’s options open.

Football. Tennis. Table tennis. College. Fulfilling his duties as secretary of the local Brampton Youth Group. Keeping an eye on his mum and two younger brothers. That was George Robledo in his mid-teens, as war raged around the globe. But increasingly, football was beginning to govern his waking hours. Within days of Germany invading Poland, a decision had been taken to abandon the Football League fixture programme on the premise that large groups of people gathering together in the same place probably wasn’t a good idea. However, after a few weeks the government chose to permit the playing of friendly matches, with the Football Association establishing a regional Wartime League in order to cut down on non-essential travel. With many sportsmen either on active service or performing other vital duties, a special ‘guest player’ system was established where a club could field any team member, registered or 22not, providing they could get to and from the ground on the day of the game. Football, in other words, kept ticking over. Not only that, but some clubs continued to actively pursue young talent, much as they would have done in peacetime. Which is how George, having excelled at schoolboy level, came to the attention of both Barnsley and Huddersfield Town.

It was at Belle Vue, home of Doncaster Rovers, in May 1942 that George made what can loosely be described as his first appearance for a professional football club, representing Barnsley against a Northern Command side made up of footballers serving with regiments based in the north of England. He scored twice, something which only seems to have piqued Huddersfield Town’s interest.

The following season, 1942–43, George signed on as an amateur with Huddersfield, playing just the once during Ted Magner’s relatively brief tenure as manager, in a 3–3 draw at Bradford City. That in itself appears to have made Barnsley manager Angus Seed (wryly described as ‘a sober man in a grey overcoat’ by the one-time BarnsleyChroniclejournalist turned television presenter Michael Parkinson) all the more determined to nab George and tie him down to something more substantial. On 22 July 1943 he did just that, signing the rookie to a one-year professional contract worth £2 per match under the watchful eye of George’s uncle Frank Oliver, who acted as a co-signature due to his nephew still being seventeen.

‘He is one of the finest lads I have seen and I predict a great future for him,’ Seed, with great perception, told the BarnsleyChronicle reporter covering the story of George’s signing. As Parkinson also wrote of Seed, ‘What he lacked in personality he made up for in an ability to spot rare talent, which kept him in the job for nearly 23twenty years.’ George, as it turned out, would prove to be one of his greatest finds, if not the greatest. And there were more than a few – Danny Blanchflower and Tommy Taylor, to name just two.

He was young. He was confident. He was strong. He was, as they say, fit as a butcher’s dog. And now George was officially a professional football player, ready to face the somewhat make-do-and-mend world of the Wartime League.

At which point the war itself – or to be more precise, Ernest Bevin – intervened. 24

3

Working Class Hero

‘Themachinesthatkeepusaliveandthemachinesthatmakemachinesarealldirectlyorindirectlydependentoncoal.InthemetabolismoftheWesternworld,thecoalminerissecondinimportanceonlytothemanwhoploughsthesoil.’

– George Orwell

On Tuesday 12 October 1943, Gwilym Lloyd George, Minister of Fuel and Power in Britain’s wartime coalition government, announced in the House of Commons that some conscripts, instead of going to fight, would in future be directed to the mines. At the start of the war, the powers that be at Westminster rather short-sightedly sent thousands of young coal miners into the armed forces. These miners, by and large, weren’t replaced because the men who might otherwise have filled their shoes were also conscripted into the forces. By the autumn of 1943, supplies of coal to fuel the war effort and heat domestic homes during the impending winter were running horribly low – this at a time when the UK also depended on coal to power its ships and trains. Throw in a 26combination of poor industrial relations, discontent over wages and absenteeism (often down to sickness, the burden of the work underground having fallen to older miners) and Britain was at the point where something had to give.

Three months later, on 2 December, Ernest Bevin, Minister of Labour and National Service, came to Parliament to put some flesh on the bones of the policy. Over the next five months, 30,000 men aged from eighteen to twenty-five would be redirected to what became known in some quarters as the ‘underground front’. In practice, this meant one in ten young men called up were, as of immediate effect, going to work in the mines. They were chosen by lot. If your registration number came out, then you were a ‘Bevin Boy’ destined for a mine. This was not up for debate. If you didn’t go, prison beckoned.

Throughout the remainder of the war, Bevin Boys were often targets of abuse, regarded by some as cowards or draft dodgers. The police frequently stopped them as possible deserters. Once hostilities were over, the Bevin Boys received no medals for their contribution to the war effort, with official recognition being conferred by the British government as late as 1995. It’s fair to say dogs have been treated better.

On 14 April 1944, George Robledo turned eighteen years old. Despite wanting to further his fledgling career as a football player, he was also keen to do his bit by fighting for his adopted country. Ernest Bevin had other ideas. Out came George’s registration number in the lot. Whether he liked it or not, he was heading for the mines.

The first Bevin Boys from outside the Dearne Valley arrived in 27the area at the start of 1944, being billeted in the town of Wombwell. George, needless to say, didn’t have quite so far to travel. The miners of West Melton, and there were plenty of them, tended to work at one of three pits – Wath Main Colliery, Manvers Main Colliery or Cortonwood (the proposed closure of which proved to be the spark that ignited the long and bitter miners’ strike of 1984–85). George landed Wath Main.

And so began thirteen months juggling professional football and mining. It started with six weeks’ training, four spent in a classroom in Doncaster followed by two at Wath Main itself. Next came four weeks of supervised work below ground alongside an experienced miner. Eventually, George was let loose on the coalface itself, working what was known as the Silkstone Seam, renowned for its high-quality coal that gave off considerable heat and left little ash after burning.

George wore his helmet and his steel-capped safety boots – and he needed to. At that point in time, coal mining was regarded as the most dangerous job in the UK. Thousands of men (some of them barely men at that) were killed or seriously injured while doing it, with many more contracting industrial diseases. The danger came from the difficult working conditions and the gases that were released through the extraction of coal. At least fifty-nine men perished at Wath Main during its 112-year existence, including seven in one go on 24 February 1930, killed when firedamp (the term used for flammable gas found in a coal mine) was ignited by, irony of ironies, a safety lamp. Thirteen men had died as recently as February 1942 in an explosion at the nearby Barnsley Main Colliery, a number that still pales in comparison to the 361 miners and rescuers who lost 28their lives in the very same neighbourhood following a series of blasts at Oaks Colliery on 12 December 1866.

Nevertheless, coal mining remained a proud career choice. Those who did it derived satisfaction from their craft and the contribution they made to the national economy. George, born and raised in mining communities on opposite sides of the world, got that and so fitted in well in the dark and dangerous world below. He was productive in terms of digging out coal, once being told to ‘slow up’ by a laconic older miner charged with filling the wagons waiting to transport the black stuff to the surface. That, along with his burgeoning reputation as a footballer, meant he was spared the unfair flak directed at many Bevin Boys.

It also helped that George understood the concept of teamwork. As far as he was concerned, being a miner was very much like playing football in that you had to have complete trust in those around you. Except, of course, there was far more at stake down there. Lives, which could get taken at any moment by explosions, gas, fire or inrushes of water, were on the line. Down there, if you didn’t work together you and everyone else might never see daylight again.

Besides trust and teamwork, there were other similarities between mining and football that George warmed to. The sense of humour, camaraderie and spirit that abounded at Wath Main really wasn’t so different to what he experienced in the dressing room at Oakwell, home to Barnsley Football Club since 1887.

‘We will build a soccer team that the rugbyites will not crush,’ the Reverend Tiverton Preedy, founder of what was initially called Barnsley St Peter’s FC, had declared on the club’s inception, keen to instil some good Christian values into what had until then been 29