8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

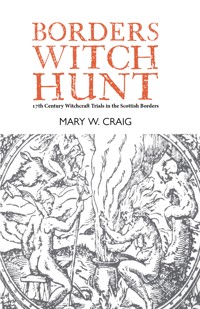

The years between 1600 and 1700 were a period of war, famine, plague and religious upheaval in Scotland.A time when ordinary women, and men, of the Scottish Borders who fell under the suspicion of the Kirk would face interrogation and torture.A time when fear of Auld Nick turned the world upside down and the cry of witch would almost always lead to the rope and the flame.Mary Craig explores this tremulous period of Scottish history and examines the causes and effects of the 17th century witchcraft trials and executions in the Scottish Borders.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 357

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

First published 2020

eISBN: 978-1-910022-26-9

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Mary W. Craig 2020

Speed Southern Scotland below Marches 17th century map © Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Contents

Acknowledgements

Note

Summis desiderantes affectibus

Timeline of events

Introduction

1Belief: Witchcraft in the 17th century

2History: The Borders in the 17th century

3Peebles, 1629: ‘vehementlie suspect of wytchcraft’

4Melrose, 1629: ‘four guid men’

5Duns, 1630: ‘petition the King’

6Eyemouth, 1634: ‘the Devil be in your feet’

7Stow, 1649: ‘ane great syckness’

8Lauder, 1649: ‘the Devil is a lyar’

9Kelso, 1662: ‘pilliewinkles upon her fingers… a grevious torture’

10Gallowshiels, 1668: ‘her petticoats a’ agape’

11Jedburgh, 1671: ‘ane sterving conditione’

12Stobo, 1679: ‘the dumb man in the correction house’

13Coldingham, 1694: ‘burn seven or eight of them’

14Selkirk, 1700: ‘the drier ye are, the better ye’ll burn’

Conclusion

Appendix A: The cultural background to the witchcraft trials

Appendix B: The Scottish witch trials: numbers and locations

Appendix C: The Borders witch trials: numbers tried and locations

Appendix D: Places to visit

Appendix E: Trace your ancestors in the Borders

Bibliography

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

THIS BOOK WAS written in an attempt to cast light on the social history surrounding the witchcraft trials that took place in the Scottish Borders in the 17th century. Much has been written about the phenomenon of witchcraft in Scotland but the combination of events and beliefs that occurred and held sway in the Scottish Borders give the trials there a particular identity and they remain an area for much study.

The records held at the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland have proved invaluable in compiling this book, as has the University of Edinburgh’s Survey of Scottish Witchcraft and the Scottish Borders Archive service in Hawick. I wish to thank the Museum of Witchcraft in Boscastle, Cornwall, for the use of several woodcut images and general background information. Further thanks are due to Rhiannon Hunt who supplied the other illustrative artwork in this book and Mike and Jessica Troughton for their photographs. Finally, thanks are due to the editorial team at Luath Press for their help in producing this book.

Mary W. Craig

Note

SOME OF THE following chapters contain descriptions of crowd reactions. Some of these descriptions come directly from contemporary records, others are imagined responses based on those contemporary records.

The geographical area covered by this book constitutes the Scottish Borders region today. This did not exist in the 17th century. Some of the land in the north was, at that time, part of Midlothian while the southern border with England remained debatable for a large part of its length. Galashiels was known as Gallowshiels in the 17th century.

Summis desiderantes affectibus

The Summis desiderantes affectibus (desiring with supreme ardour) was a Papal Bull regarding witchcraft issued by Pope Innocent VIII on 5 December 1484. The Bull was written in response to a request by the Dominican Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer for the authority to prosecute witchcraft in Germany after he was refused assistance by the local ecclesiastical authorities. The Bull did not confer any new powers but ratified the existing authority the Inquisition held to prosecute witches. It gave approval for the Inquisition to proceed ‘correcting, imprisoning, punishing and chastising’ such persons as it deemed guilty and urged local authorities to cooperate with the inquisitors and threatened those who impeded their work with excommunication.

‘It being known that many persons of both sexes, unmindful of their own salvation and straying from the Catholic Faith, have abandoned themselves to devils, incubi and succubi, and by their incantations, spells, conjurations, and other accursed charms and crafts, enormities and horrid offences, have slain infants yet in the mother’s womb, as also the offspring of cattle, have blasted the produce of the earth, the grapes of the vine, the fruits of the trees, nay, men and women, beasts of burden, herd-beasts, as well as animals of other kinds, vineyards, orchards, meadows, pasture-land, corn, wheat, and all other cereals; these wretches furthermore afflict and torment men and women, beasts of burden, herd-beasts, as well as animals of other kinds, with terrible and piteous pains and sore diseases, both internal and external; they hinder men from performing the sexual act and women from conceiving, whence husbands cannot know their wives nor wives receive their husbands; over and above this, they blasphemously renounce that Faith which is theirs by the Sacrament of Baptism, and at the instigation of the Enemy of Mankind they do not shrink from committing and perpetrating the foulest abominations and filthiest excesses to the deadly peril of their own souls, whereby they outrage the Divine Majesty and are a cause of scandal and danger to very many.’ Papal Bull of Pope Innocent VIII, 14841

Timeline of events

1484Pope Innocent VIII published his Papal Bull against witches1563Scottish Witchcraft Act passed1564John Knox declares witches to be enemies of God1590North Berwick witches attempt to drown King James VI1597King James VI publishes his great book on witchcraft, Daemonologie1600Plague in the Borders1607Plague in the Borders1623Famine in the Borders1624Plague in the Borders1625King Charles I marries Henrietta Maria, a French Catholic and issues the Act of Revocation in Scotland, revoking all gifts of royal or church land made to the nobility1630Plague in the Borders1635Plague and famine in the Borders1637Charles attempts to impose Anglican services on the Presbyterian Church of Scotland; Jenny Geddes starts riots at St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh1638Signing of the National Covenant in Scotland1639First Bishops’ War1640General Assembly passes the First Condemnatory Act against witches1640Second Bishops’ War1643General Assembly passes the Second Condemnatory Act against witches1644General Assembly passes the Third Condemnatory Act against witches1644Scottish Civil War1644Plague and famine in the Borders1645General Assembly passes the Fourth Condemnatory Act against witches1645Battle of Philiphaugh outside Selkirk1648Famine in the Borders1649General Assembly passes the Fifth Condemnatory Act against witches1649Execution of King Charles I1649Cromwell invades Scotland1675Famine in the Borders1677-1682A number of prominent members of the aristocracy in the court of Louis xiv at Versailles were sentenced on charges of poisoning and witchcraft1692Salem witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts1695Famine in the Borders1700Last witch executed in the Borders1722Last witch executed in Scotland1736The Scottish Witchcraft Act was formally repealed by Parliament and replaced with the Witchcraft Act of Great Britain which placed much greater emphasis on real proofs and evidence1773The Divines of the Associated Presbytery of Scotland passed a resolution affirming their belief in witchcraft1944Trial of Helen Duncan, known as Hellish Nell, the last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act1950sA series of investigations and hearings chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy were held in an effort to expose the supposed communist infiltration of various areas of the us Government; became known as a ‘witchunt’1952Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible used the Salem witch trials as a metaphor for McCarthyism2003Around 750 people are killed as witches in Assam and West Bengal, India2006-2008Between 25,000 and 50,000 children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, accused of witchcraft Fawza Falih Muhammad Ali was condemned to death for practising witchcraft2008President Kikwete of Tanzania publicly condemned witchdoctors for killing albinos for their body parts, which are thought to bring good luck; at least 25 albinos have been murdered between March 2007 and 2017 At least 11 people accused of witchcraft were burned to death by a mob in Kenya More than 50 people were killed in two Highlands provinces of Papua New Guinea for allegedly practising witchcraft2010Amah Hemmah was accused of witchcraft and burned to death in Ghana2011Amina Bint Abdulhalim Nassar was beheaded for practising witchcraft and sorcery in Saudi Arabia2012Muree bin Ali Al Asiri was beheaded on charges of sorcery and witchcraft in Saudi Arabia201369 reported cases of accusations of women performing witchcraft in Nepal2019In Fijia, a father blamed witchcraft for the death of his familyIntroduction

17TH CENTURY SCOTLAND started with plague and ended with famine and, between those two events, the lives of nobles and peasants were turned upside down. The crowns of Scotland and England were united; a King lost his head; men the length of the British Isles went to war over the correct form of worship; a monarchy was turned into a republic and back again and the form of parliamentary rule was changed out of all recognition. Faced with apparent chaos and the breakdown of the natural order of things, a wave of fear and hysteria travelled across the countryside that resulted in hundreds of accusations of witchcraft.

This witch hysteria was greatest in Scotland and the towns and villages of the Scottish Borders in particular saw local men and women accused and sentenced to be worriet (strangled) to death and their bodies burned. Trials were conducted in all four of the Border counties: Berwickshire, Peebleshire, Selkirkshire and Roxburghshire. In towns and villages alike, accusations generated by fear, hysteria and, in some cases, malice were made, investigations held and victims worriet and burned.

The total numbers of those who died may never be fully known but piecing together what records exist between 1600 and 1700, some 352 known trials of witches took place in the Borders area which resulted in 221 executions. It has been estimated that the true figure may be even higher. As these are only the figures for official trials, many more accusations must have been made that did not make it to the courts for one reason or another. With a population of only around 70,000, this denotes a higher than average number of accusations. More witches were accused, tried and executed in the Scottish Borders than in any other area of Scotland except Edinburgh and the Lothians. The accusations and trials of witches in Scotland tended to occur in distinct periods, eg 1629, 1649, 1661. While this pattern is also seen in the Borders, there is also a much more consistent level of single cases being brought in the various towns and villages of the region. Between the main periods of high activity, the Borders could always be relied on to be bringing one or two cases when the rest of the country was relatively quiet. The question is why should the Borders have such a high rate of cases for such a low level of population and why, when the apparent threat of witchcraft was dormant in the rest of the country, did the Borders continue to carry out cases? The official records also show that the Borders had very high levels of guilty sentences and executions. At least 63 per cent of those brought to trial in the Borders were executed; the Scottish average was around 55 per cent. These figures do not allow for circumstances where the fate of the accused is unknown due to incomplete or missing records.

The people of the Borders, in common with most of Europe, had an innocent belief in the power of spirits and faeries reaching back to pre-Christian times. This had been, relatively, tolerated in the early days of Christianity. During the medieval period as the church consolidated its power these beliefs start to be seen as part of the Devil’s realm. This developed until by the 16th century European theologians started to believe that there were actually people who worshipped the Devil: witches. The Reformation ‘proved’ to the new Protestant faith that the Devil and his witches with roaming the land. Who else could be responsible for war, famine and plague? The Scottish Kirk, God’s Elect, declared war on Auld Nick. But while the Devil was sowing chaos across the land blasting entire communities with the likes of war, he had also sent out his handmaidens to destroy communities from within. To the modern mind, it is obvious that the crimes witches were accused of are impossible. You cannot cause the harvest to fail by casting a spell. However, in the 17th century it was perfectly believable that an individual could cause the harvest to fail. Everyone believed in the existence of God and the Devil and their power. A good Christian could pray to God for help; a witch, aided by the Devil, could cast a spell and cause the harvest to fail.

The Borders was, like many parts of Scotland at the time, an intensely rural area where life for many was lived on the margins and one poor harvest or a cow going sick could result in death from starvation for a family. The line between life and death for many rural poor was a thin one, especially for the young, the old and the already sick. Women caring for the sick or helping as midwives were easy prey for those seeking to blame someone for their own misfortune. As women were, predominantly, in control of the household’s food supply, they were also those best placed to curdle a neighbour’s milk or spoil a friend’s ale. However, rural life was equally harsh across Scotland and the risks of illness and spoiled foods were not particular to the Borders. The reasons behind accusations and the nature of Scottish witch hunts have been extensively documented elsewhere (by Maxwell-Stuart and others) but little, if any, attention has been paid to the particular nature of the witch hunts in the Border lands. Why, with a relatively small and sparse population, did the Borders manifest such a large crop of witches and why did the local presbytery appear to pursue them with such evident vigour? Why, also, did the Borders have trials that ranged from one individual witch to trials involving large numbers of individuals? And why was the Borders home to witches of both genders and all ages?

Was it the geography of the Borders? By its very location, the area had borne the brunt of the frequent wars between Scotland and England. The constant and continual uncertainty and proximity of death and destruction would have played their part in the local psyche. The dark and seemingly uncontrollable forces of war might have become mirrored in many communities by the apparent existence of the equally dark and uncontrollable forces of witchcraft.

Was it the history of the reivers? As Border families had ridden stealing and burning as they went, did witches too creep through the night to steal and ultimately burn? Was it the low number of families involved as ministers, commissioners, sheriffs and baillies? Related by blood or marriage, these men controlled the process from initial investigation, through trial to final execution. And for most an accusation would result in execution.

Or was it something in the mentality of the Borders’ Kirk? Were they fearful of the Catholics that still lurked in the north of England? There were uprisings by Catholics in Northumbria as late as 1537 and the Percies and Nevilles and all of their followers were staunch Catholics and previously reivers. Had the Borders clergy been shamed by the religious fervour of the Covenanters in Galloway? The Covenanters had literally fought for their faith, the Borderers had not. Or had the very piety of the Borders become not a blessing from God but a curse by the Devil? Had their Godliness released a plague of witches upon their own Kirk?

1

Belief

Witchcraft in the 17th century

HUMAN CULTURE MOVES slowly and at different speeds for different peoples. It is not tidy and does not fit neatly into nicely labelled time periods. Beliefs and behaviours spill over from one time to another and may mix and evolve over the centuries. This is true for many aspects of human culture, including the spiritual. The Scottish Borders has been populated since around 6500 BC and the evidence suggests that these early Borderers in common with many early societies worshipped various gods or supernatural creatures. The world for these early Borderers could be an unpredictable and frightening place with sudden storms, floods, illnesses and harvest failure. Events outwith human control could mean life or death. In order to make sense of such happenings and in the hope of lessening their occurrence, early Borderers appeased the gods through supplications and prayers. The shadowy gods lurked in many places, most notably water, and a frequent sacrifice was of a metal object cast into water. Metal was precious and water was thought of as a gateway between the human world and the world of the gods. Not everyone could afford to offer a metal sacrifice and food and drink was often offered instead. Magical amulets offered protection from the wrath of certain gods and supplications to others were pleas for good luck.

While various peoples arrived as settlers or invaders, these religious beliefs remained relatively unchanged for several centuries. Around the 5th century ad, the first Christians arrived in the Borders. The new faith took some time to establish itself and, even after Christianity was established, the two beliefs co-existed for some considerable time. Syncretism, the amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, is seen across human culture and the arrival of Christianity into the Borders was no exception. Blending and cross-fertilisation between the old and the new gave the people enough spiritual solace to ensure ongoing followers for both. The festivals around the winter solstice on 21 December mixed with celebrations of Christ’s birth. Equally offerings of thanksgiving at the return of the good weather in spring were subsumed into the Easter celebrations of the resurrected Christ.

Initially the changes were slight, however, as the centuries wound on Christianity became more dominant. As the territories of the old Roman Empire were Christianised, so too were the members of the ruling orders and those engaged in trade. But although Christianised, many people retained traditions and practices from their pre-Christian past. Initially the early Christian church accepted many of these traditions but, as the church strengthened and grew, its tolerance diminished.

There were three main points of contention: a single Christian God rather than several pagan gods; the Christian separation of good and evil into two different entities, while the old beliefs had contented itself with a duality within their gods; and one single male God within Christianity rather than the female as well as male gods of before. In addition, the clarity that was self-evident to Christians was confusing to pagans. Christianity was clear: there was one God, who was good and male and there was one evil Devil. But this surface simplicity quickly gave way as it was revealed that the one God was also Christ the son and the Holy Spirit. And why had the one good god, who had created all, created an evil Devil? To the old believers, this sounded curiously like multiple gods who were both good and evil and what was the Virgin Mary if not a female god?

Theological arguments aside, the day-to-day business of life was little altered by the new religion. Appeasing the gods for a good harvest mutated into the priest blessing the fields at spring sowing. Thanking the gods for an abundant crop became the harvest thanksgiving festival at the local church. In rural areas, a reasonable, if unspoken, accommodation was reached at which a priest might turn a blind eye to certain superstitions, as the old beliefs were now called, as long as there was a genuine belief in God. A simple faith was accepted, albeit one which did not bear too much scrutiny.

This relatively peaceful co-existence could not last forever. By the 16th century, an unthinking, non-questioning belief was no longer good enough and the Reformation jolted rural areas out of their religious torpor. The new focus on personal salvation and the word of the Bible removed many of the ritual elements of Catholicism; those very elements which had held reassuring remnants of the old folk beliefs. Correct theology was no longer the preserve of priests and bishops but was to be understood by all. As the Reformation progressed in Scotland, more and more people converted to the Protestant faith. However, for many, Protestant theology was ill-equipped to deal with the complexities of everyday life and they simply brought their pagan beliefs with them.

Those beliefs were expressed in many ways but were dominated by death. Death was a common visitor in the many rural areas of Scotland – as indeed it was for most of rural Europe – including the Borders, through illness, wars or famine. The old beliefs had offered a method of articulating fears and dealing with the spirits of the dead. This had been continued by the Catholic faith with its masses for the dead. The ways of the old gods or the new God could not be understood but religious ritual could provide comfort. The new Protestant faith singularly failed to provide a similar method of comfort. The new faith expected individuals to think about their relationship with God. Were they saved or damned? Who could know for certain? Individuals were further expected to think about their faith at all times. But thinking about religion did not alter the reality of rural life. The harvest still failed, illness still came, family members still died. And everyone knew that the spirits of the dead had to be appeased to protect the living from their anger and to ease their passage into the other world. The lack of understanding by the Protestant clergy of this basic underlying belief would prove disastrous. Ghosts, spirits and apparitions were a fact of life and if the new faith would not or could not cater to this belief, and the Catholic faith was branded diabolical, then the people would simply reach back to the old days for succour; Halloween would give them that aid. Condemned outright by the Kirk, Halloween would prove to be a tenacious relic of the pagan beliefs.

Try as it might, the Christian church could not shake the festival of Halloween. But what it could and did do was to demonise those who participated. The lack of understanding from the Kirk and the intransigence of ordinary people made any accommodation impossible. As far as the Christian fathers were concerned, Halloween with its necromancy was simple Devil worship by another name. For rural people, however, while they retained their belief in God and attended the Kirk on a Sunday, the folk beliefs in talking to spirits and ghosts remained. The local minster might talk of the riches of heaven in the life to come but a spinning apple might give some forewarning of a bad winter in the here and now.

The Kirk believed that witches had renounced their Christianity and made a pact or covenant with the Devil. The people, however, did not think in such formalised terms. Carrying a lucky amulet was not seen by Borders villagers as anti-Christian, but merely a normal activity, albeit a cultural throwback to the old ways. They were able to accommodate their Christianity and their superstition; the Kirk was not.

What had previously been tolerated, to a degree, by the Catholic Church was anathema to the new Presbyterian Kirk. Practices that had been innocently pursued were now castigated and given a diabolical basis. In the early days of the Kirk’s witch hunts, people confessed, not because they were mad or confused or even tortured. They confessed that, yes, they had left an offering to the man with the black hat or had looked in water to find stolen property. These were the common activities of most people. While some were, no doubt, witches in the eyes of both themselves and their neighbours, the vast majority were just ordinary people with superstitious beliefs. Their confessions were true. It was simply that what was a normal procedure for them and had been practised for generations had become an act of evil to the Kirk.

While many did confess to making a pact with the Devil, care must be taken over this. Some of those who confessed to making a covenant with Auld Nick, as the Devil was occasionally known, did genuinely believe that they had met him. However, it must be remembered that the fervent beliefs of the interrogators led them to try to discover a diabolic element to witchcraft and frame their questioning accordingly. This was not a case of manipulating the questions to get the answers they wanted but a matter of stressing the questions that they felt would allow them to get at the real truth of the matter: the Devil and his works. When witches said they made a covenant, this was not Devil worship as a cult – an alternative religious belief to Christianity – it was more a pact between one person and Auld Nick. The old gods had been creatures with whom an individual could bargain; I will sacrifice in order for you to ensure a good harvest or, if you give me a male child, I will make a sacrifice in your honour. However, the Protestant Reformation had introduced a new aspect of personal responsibility and a covenant with God. Witches were damned, therefore, for their choice of the Devil over God and their method of interaction with him which mocked the covenant with the Presbyterian God.

Witches’ confessions were not the fevered tales of Gothic horror. They were often much more mundane, coming from sometimes lonely, sometimes poor people, who believed they had met the Devil and that he had made them promises of power over their enemies or ample food for the winter. They made a covenant with the Devil and got revenge on those who had slighted them. A neighbour, who years previously had refused to help, would lose a cow. An unpaid debt would see ale soured. There was little if any flying around on broomsticks or turning your neighbour into a toad. These were everyday matters: causing the milk of a neighbour’s cow to dry up, spoiling ale, raising a storm to ruin crops. But everyday matters though they were, they were also matters of life and death. For the rural poor of the Borders life was a constant struggle and many lived on the precarious edge between survival and destitution. If a rich farmer’s crops were ruined by a storm, he might be able to buy in food to feed his family. If a poor tenant farmer lost his crops, his family faced several lean weeks. For a farm labourer, a crop failure would mean no wages and possible starvation.

It was women who were responsible for maintaining the home. Ensuring the family was fed was female work; churning milk to make butter, brewing ale for the men to drink. If a cow went dry or the ale soured, it was the women who were to blame. What could start as a neighbourhood quarrel would all too soon descend into darker waters. Cursing a neighbour’s crops or kye (cattle) or wishing illness on a horse or even a child as revenge for an apparent injury with little risk of capture was too easy a lure to reject. It is rare in any of the trial records to hear of witches being promised or seeking after great riches. These were years of food shortages and war. You were much more likely to survive through the winter with your kye alive and healthy than with a hoard of gold beneath your bed.

In the vast majority of cases, the accusations that arose from such household quarrels and the curses of the injured party were considered witchcraft by the Kirk. In some of the cases, albeit the minority, the injured parties believed themselves to be witches. While most 17th century Scots were merely superstitious, continuing the ritual of the old ways while attending the Kirk on a Sunday, there were those who were known as and believed themselves to be witches. Sought out by their neighbours in times of trouble, they used their craft in ways that threatened Kirk authority. Like devout members of the Kirk, witches believed in a supernatural being who would reward you for worshipping him and following his code of behaviour. Unfortunately for the witches, their supernatural being was unacceptable to the powers that be.

The religious and superstitious beliefs of most people in the 17th century were no different from those held in the 16th century, or for that matter the beliefs that would prevail in the 18th century. What was to prove fatal was the inability of the Kirk to accept any deviation from the prescribed dogma of the day, and the inability of ordinary folk to dissemble. It has been suggested that one of the reasons why the nobility were rarely arrested for witchcraft was not that they did not believe in witches or indulge in witchcraft; it was rather that they were better liars and better able to hide their superstitious beliefs behind a façade of Christian respectability than the folk of the Borders.

It is likely that of all those arrested for witchcraft some would, no doubt, have described themselves as witches. The vast majority were trying to survive in a harsh world as best they could and were innocent of the charges brought against them.

2

History

The Borders in the 17th century

THE HUNT FOR witches in the Scottish Borders appears to have been characterised by levels of religious zeal seldom seen elsewhere. But this religious zeal should not be thought of as an excuse to attack women (although women were predominantly accused) nor should it be thought of as an organisation out of control and drunk on power, although again there were instances of individuals abusing their position of authority. Both ideals are somewhat anachronistic. The religious zeal with which the Borders Kirk pursued witches was based on a genuine fear: fear of the Devil. As the century progressed, the Borders Kirk came to believe themselves to be under attack by the Devil himself. Their reasoning was threefold.

Firstly, the Kirk believed that they were God’s Elect. A central part of Jean Calvin’s theology taught that all events had been preordained by God; that He had willed eternal damnation for some and salvation for others. Book III of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion detailed ‘the eternal election, by which God has predestinated some to salvation, and others to destruction’.2 As religious Scots that had chosen Calvinism, the members of the Kirk believed they had already been elected by God for salvation. However, this conviction led to a degree of unease as no one could know for sure if they were saved. Proof would be needed. This then led to the second element of their argument. If they were indeed God’s Elect then they would be targeted by the Devil for attack. He had no reason to attack his own but would surely turn his malice towards the most godly, God’s Elect. The Kirk’s very godliness, therefore, made it a target. And just as they (the Kirk) covered all of Scotland, so the Devil would unleash a horde of his followers (witches) across the land to attack them.

As the 17th century developed, this became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. The more godly the Kirk, the greater the number of attacks by witches and so, perversely, the Kirk became drawn into denouncing more and more witches. This prophecy was based on a belief in the Kirk’s status as God’s Elect and a genuine fear of the Devil and his works, it was ‘proved’, in the mind of the clergy, by the chaos of the civil and religious wars of the century and the repeated occurrences of plague and famine. This third element of the Kirk’s reasoning had a particular resonance in the Scottish Borders as its geographical location resulted in a perfect storm of events and circumstances. The Borders became the sight of repeated battles as Royalists, parliamentarians and Covenanters fought for control. Even when the various armies were not fighting in the Borders, they wrought destruction as they passed through on the road to Edinburgh or Newcastle. Armies at that time lived off the land and a passing troop of soldiers could strip a community of all of its food stores in a day. Those who resisted were assaulted, as were any young women who caught the eye of the soldiers. In addition, the Borders Kirk was conscious of the proximity of the Catholics in the north of England who had resolutely failed to abandon the old, and now very suspect, faith. Had not Knox himself preached that Catholics were in league with the Devil? And finally, disease and harvest failure visited the Borders on multiple occasions over the century, devastating many communities. The four horsemen of pestilence, war, famine and death rode across the land, or so it seemed. Beleaguered as the Borders Kirk felt themselves to be, they developed something of a siege mentality. Under attack by war, devastated by harvest failures and plague, threatened by Catholics, the religious fervour of the Borders Kirk quickly became hysteria as the events of the century pushed it from the spiritual ecstasy of being God’s Elect into the delusional frenzy of a church under attack by Auld Nick himself.

To put the Scottish witch hunts into some perspective, the level of witchcraft trials in Scotland per head of population was one of the highest in Europe and ten times the rate in neighbouring England. The rate of trials and executions in the Borders was the second highest in Scotland despite the area having a relatively low population.

The 17th century saw Scotland still reeling from the effects of the great religious wars of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. The Reformation that had swept most of northern Europe arrived in Scotland in various forms in the early 16th century. The beliefs of Luther and Calvin and their criticisms of the church were vigorously debated by many including John Knox of Haddington. One of Calvin’s most fervent followers, Knox’s influence on the direction of the new church was pivotal. After narrowly escaping arrest alongside his mentor, George Wishart, Knox was captured by the French before being released when he took refuge in England and served as royal Chaplain to Edward VI. After the accession of Catholic Mary Tudor to the English throne, Knox resigned his post and fled to Geneva where he met Calvin. On meeting Calvin, Knox asked a series of revealing questions. Could a minor rule by divine right? Should people obey ungodly or idolatrous rulers? What party should godly persons follow if they resisted an idolatrous ruler? And could a female rule and transfer sovereignty to her husband? These questions were highly political and related, in the main, to the rule of Mary Tudor. Although Calvin, ever the politician, gave somewhat cautious answers to Knox, the issue of women and power would remain integral to much of Knox’s thinking for the rest of his life. Knox spent his time on the continent thinking and reading on Calvin’s work and reworking the theology into his own world view and understanding of God. This became a worldview comprising rigid certainty in the correctness of Calvinist Protestantism and an unbending opposition to anything which appeared to transgress that belief.

The Protestant Reformation in Scotland was Calvinist in nature and became Knoxian in execution. In 1557, the Lords of the Congregation drew up their covenant to ‘maintain, set forth, and establish the most blessed Word of God and his Congregation.’3 When the Scottish Parliament convened on 1 August 1560, they set up a ‘committee of the articles’ consisting of Knox and five other ministers. This committee was to draw up a new confession of faith. Knox presented his recommendations in the Scots Confession which called for a condemnation of papal authority, a restoration of early Church discipline and a redistribution of Church wealth to the ministry and the poor. Parliament approved the Scots Confession of Faith and passed three Acts that destroyed the old Catholic faith in Scotland: the abolition of the jurisdiction of the Pope in Scotland; the condemnation of all doctrine and practice contrary to the reformed faith; and the outlawing of the celebration of mass in Scotland. On paper, at least, the Reformation was established in Scotland. In practice, it would prove to be a somewhat different matter.

Knox and his colleagues were asked to undertake the organisation of the reformed church. After several months of work, they produced the Book of Discipline4 which set out the organisation of the new church. The Second Book of Discipline was published in 1578 after the death of Knox and the abdication of Mary, Queen of Scots. It was a reiteration of Knox’s values and firmly established Presbyterianism in Scotland. The new church organisation set out in the Book of Discipline allowed each Kirk a relatively large degree of autonomy. Each congregation could choose or reject their own minister; although, once chosen, they could not fire him. Each parish was to be self-supporting and bishops were replaced by a group of 10–12 ‘superintendents’. The new Kirk was to be financed from the patrimony of the Roman Catholic Church. This proved somewhat contentious as much of the land that had been confiscated from the Catholic Church had been given to members of the nobility who were loathe to relinquish it – especially those who still retained a belief in the old faith. A further measure which rankled with the nobility was for certain areas of the law to be placed under ecclesiastical authority, diminishing, in the eyes of those nobles, their own power. The removal of the power of Rome had been welcomed by much of the nobility, no matter their faith, as it was seen as an opportunity to consolidate and in some cases extend their own authority. The increased autonomy of the Kirk with its superintendents was therefore an undesirable element in the new reformed Scotland and one that was to be resisted.

The Parliament did not, in fact, approve the Book of Discipline due, in part, to financial reasons and stiff opposition from many nobles, but also due to the imminent arrival of Mary, Queen of Scots, which put all matters, especially religious, on hold. However, the basic structure of the new Kirk had been established. The autonomy given to individual Kirks would prove a dangerous element later when witchcraft accusations were made. With no need for ministers to seek advice or approval from a higher church authority, the Borders Kirk had no restraining voice to caution.

A second element that would exert a strong influence on the 17th Scottish Kirk was Knox’s attitude towards both witches and women, which had continued to develop since his initial struggles with Mary, Queen of Scots. His famous pamphlet, The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women5, may have been aimed at powerful women such as Mary, Queen of Scots and Mary Tudor of England but, like all such documents, once printed it took on a life of its own and percolated into the psyche of many. Its central message – that power was not a state natural to women, that women would always seek power over men and that women who sought power were to be feared – struck a chord with many across Scotland, especially those in the Kirk and the nobility. The Reformation had several unintended consequences, one of which was that educated noble women started to read their Bibles. Without the need of a male priest to explain or intercede for them with God, some of these women questioned their need for men in their day-to-day lives. Previous beliefs about women and their place in society were now questioned, albeit by a very small minority. The subservient role of women touched on another issue of great import to the Kirk: the matter of authority. Desperate to put the genie back in the bottle, Knox wrote his First Blast of the Trumpet, conflated any and all women with witches or potential witches and preached hellfire and damnation to any who questioned the natural order of men as superior to women. For the average Scot who still could not even read their Bible, Knox’s powerful sermons, which were repeated from many pulpits, won the day. Any fledgling notions of female emancipation were squashed and the belief that no woman was ever to be truly trusted was given religious legitimacy. This message, in combination with other factors, would play its part in the preponderance of female witchcraft victims brought to trial in Scotland.

As the Scots were Godly, so the Devil would attack us. As he needed servants, so he would use untrustworthy women. So, for Knox, witches were, as handmaidens of the Devil, quite simply the enemy of God and his people. The rooting out and execution of witches was, therefore, nothing less than war.

For all those that would draw us from God (be they Kings or Quenes) being of the Devil’s nature, are enemyis unto God, and therefore will God that in such cases we declare ourselves enemyis unto them.6

The understanding that witches were the servants of the Devil accorded perfectly with Knox’s view of women as creatures subservient to men. The alternative view that witches were independent beings with a degree of power was simply unthinkable. This insistence by Knox on a link between witchcraft and the Devil merely served to give a solid base to the Kirk’s later understanding and treatment of witches; a base that lasted until the end of the 17th century. The political and religious upheavals of the 17th century all centred on the matter of authority. The Reformation had fought long and hard to rid society of the ‘false authority’ of popes and priests. True authority came solely from the word of God and the Kirk was the true keeper of that word. For women to use the word of God in charms to ensure a fertile marriage bed or a good harvest was blasphemous; God was not at the beck and call of women. And, consequently, if their actions did not come from God, there was only one other place from which they could emanate: the Devil.