5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

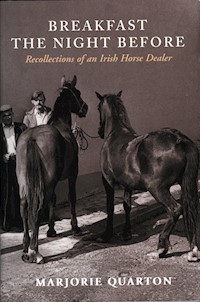

This sparkling memoir gives a personal view of Irish rural life from the Economic War of the 1930s to the farming boom and recession of the 1970s. It describes the upbringing of a Protestant only child on a farm near Nenagh in north Tipperary-an idyll interrupted by school in Dublin during the 1940s. Taking over the farm on her father's death, working the land and animals (dogs, sheep, horses, cattle), the author recounts with great humour, acuity and poignancy her dealings, from the age of seventeen, at fairs throughout the country-Limerick, Kilrush, Cahirmee, Thurles, Ballinasloe, Spancilhill, Clonmel-a lone woman in a man's world. With rare brio and eye for character, incident and idiosyncrasy, Quarton lovingly documents a world of country people, eccentric relatives, home cures and recipes, and unaffected living. Breakfast the Night Before is both entertaining and enduring.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2000

Ähnliche

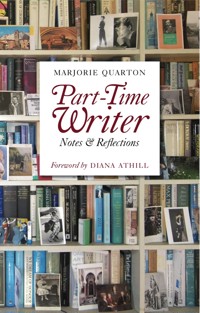

Breakfast the Night Before

RECOLLECTIONS OF AN IRISH HORSE DEALER

Marjorie Quarton

CONTENTS

Title page

Preface

ONE: Starting Young

TWO: Family Glimpses

THREE: Horse Mad

FOUR: Dublin in Wartime and Desperate Remedies

FIVE: Down on the Farm

SIX: Unwillingly to School

SEVEN: Beginner’s Luck

EIGHT: Going to the Dogs

NINE : The Life of Riley

TEN: Learning through the Pocket

ELEVEN: Breakfast the Night Before

TWELVE: Fundraising

THIRTEEN: The Creamery

FOURTEEN: Muck and Money

FIFTEEN: Never a Dull Moment?

SIXTEEN: From Point to Point

SEVENTEEN: Horses Change My Life

EIGHTEEN: Guinea-men and Old Men

NINETEEN: Some Sharp Customers

TWENTY: Weather and Clocks

TWENTY-ONE : Sheep on the Cheap

TWENTY-TWO: The Horse on the Half Crown

TWENTY-THREE: Sitting It Out

TWENTY-FOUR: A Late Vocation

Names and Locations of Horse Fairs

Copyright

PREFACE

When Breakfast the Night Before originally appeared in 1988, the publishers, André Deutsch, were in the process of changing hands and not running as smoothly as before. As a result, although briefly a bestseller, the book was reprinted only once and has been in demand ever since. It never appeared in paperback, and has been unobtainable for years. I followed it up with another memoir, Saturday’sChild (1993), very few copies of which reached Ireland. The present book consists of parts of both of these, and much more. I have omitted much that is no longer relevant, brought the events up to date, and added a lot of new material.

My life has been unusual in many ways, and often amusing, so I have tried to entertain rather than inform. I have sketched in my background and my childhood, which was of the kind called ‘privileged’. I have shown how I rejected the life mapped out for me and chose another, while remaining, of necessity, at home. I have tried, rather than mingle the various strands of my life, or lives, to take different aspects of each in turn, while gradually moving forward to the present day.

My whole life has been spent among animals; often they have taken the place of people – I have sometimes been lonely. As people live more and more in towns or suburbs, they realize less and less what it is like to be surrounded by livestock. A little boy was visiting my home some time ago and I showed him an egg, which a hen had laid under some bushes.

‘A wild egg,’ he said, astonished. ‘Is it full?’

This is not an animal book as such. Horses, dogs and farm animals share it with people who cared for and cared about animals. You can care about a creature whose destiny is to be eaten. Don’t ask me how or why. I am sure that looking after animals is good for you, therapeutic if you like. Even a hamster or a bowl of goldfish can make you feel good, so I’m told.

I am sometimes asked if it was hard to move from my cosy niche into the rough world of horse-dealing. Thinking back, I’m sure my biggest handicap was my upbringing. ‘She’s well brought up – that must count for something,’ said my parents when I strayed from the appointed path. I was crippled by that gentle rearing. I was unable to be deliberately rude; to hurt feelings (even when they begged to be hurt); to stand up for myself. ‘You’ll get nowhere in this lark,’ said a dealing friend, ‘you have a heart like butter.’ Again and again, I lost out financially because I’d been trained to think the best of everyone. Circumstances forced me to harden my butter heart, but I didn’t really change.

Horses can be addictive, and so can dealing. When addicted to both, you can easily come to grief. I survived. The stories in this book are true, except perhaps for some told to me by others. The people are real, and I have changed names only when it seemed advisable.

MARJORIE QUARTON

October 2000

CHAPTER ONE

Starting Young

I can’t remember a time when horses meant nothing to me. Born and reared on the working farm where I lived until recently, they were always there in the background when I was a child, part of my life. I used to get out of bed and sit on my window seat, listening to the carthorses in the stables, listing the different noises they made. Scrunching hay, scrunching mangolds (much louder), snuffling after mislaid grains of oats, snorting, stamping and rattling halter chains. Sometimes there would be a great, grunting sigh and a clatter as one of them lay down. They were called Andy, Dandy and Fred.

The stables were out of bounds when the horses were in. They were tied up in a row with their heels towards the door, and I had the rashness born of ignorance which is sometimes mistaken for courage. I was about four when it dawned on me that the worst that would happen to me was a not very hard slap if I were caught. Well worth the risk. I crept out to the stable and made several unsuccessful attempts to climb onto the back of the nearest horse via his manger. Fred took no notice. Then, just as I was about to give up, Andy, the biggest of the three, lay down. I climbed onto his wide, dusty back and sat there happily for ages. I suppose I was missed, for somebody came running out, my nurse probably, saw me and gave a piercing scream. At once, it seemed as if an earthquake had started. Andy rocked from side to side as he organized himself for getting up. He tipped back, paused and then seemed to shoot towards the roof. It is my first clear memory. My hands were so tightly twisted into his long, greasy mane that I couldn’t have fallen off if I’d tried. My father had to be fetched to get me down, and there was no slap.

After that, Rody, the ploughman, used sometimes to lift me onto Andy’s back. Rody, nicknamed ‘the Robin’, and his son Paddy, who inherited the nickname along with the job, worked here for more than half a century between them. Once, Rody put me up on Andy’s bare back just before it was time to go to a children’s party. I was wearing a pink frock with matching knickers and Andy had been working hard all day, carting manure. My mother was not amused.

Clearing out some old letters a few years ago, I found an essay I wrote when I was five. It was done in careful capitals and entitled MY PONY. I had written, MY PONY IS CALLED ANDY. HE IS 17 HANDS. I LOVE ANDY. HE IS DED.

Andy died of tetanus. I crouched on my window seat, watching as the vet came and went. The paraffin lamps lent extra drama to the scene and I shivered as I listened to Andy breathing. It was a frightening sound, like a giant in distress, and, suddenly, the breathing stopped … I have never forgotten that night, and never will.

I transferred my affection to Fred, who was, like Andy, a bay Clydesdale. He had a long, sorrowful white face and a perpetually drooping lower lip. I used to slip into his stall and feed him cabbage leaves, toffees, and bread and jam.

Over the stable was a musty, cobwebbed hayloft whose floor was highly unsafe. The rotten boards were patched with biscuit-tin lids. There was a ladder up to the loft, simply asking to be climbed. When it was pointed out to me that toffee might be bad for Fred’s teeth, I climbed into the loft and pushed quantities of hay down to him instead. My enthusiasm was such that I posted myself down along with the last armful and nose-dived into the manger after it. Fred seemed only mildly surprised.

Fred was named after Fred Minnitt, the friend my father had bought him from. Rody always called the horse ‘Mr Minnitt’, thinking, I suppose, that ‘Fred’ would be lacking in respect.

*

I may have suggested that I had a good deal of freedom when I was small. Not at all. My life, up to the age of nine or so, was so sheltered it was a wonder I didn’t suffocate. Most of my early memories are of walks with my nanny, securely held by the hand, bonneted and gaitered in the manner of the time.

I loved Greta, my nanny, dearly, and wouldn’t have dreamed of revealing that she pared her corns with my father’s cut-throat razor. Because of those corns, our walks weren’t the brisk affairs they were meant to be; most ended a few hundred yards up the road in some cosy cottage, where Nanny drank stewed tea and talked to her friends about deaths and diseases.

I think I was fairly well behaved, so few scoldings and fewer slaps came my way. An only child, I shared my parents’ affection with various cats and dogs but with no other child. Kept at home, I saw no other children. Nanny took me for walks while my parents walked the dogs, but I saw nothing to resent in this arrangement. My mother wondered if I was jealous of her cat when I dropped him out of an upstairs window – and this is the only occasion I can remember when she was really angry with me. In fact, I’d been told that cats always landed on their feet and was checking. It is true. However, my mother had seen Cromwell, so called because he was remarkably ugly, falling past the drawing-room window, and I failed to convince her.

*

When Nanny had her day off, my mother didn’t exactly take over, although I think she sometimes took me out in my pram. She was nervous of me, not being of the generation which bathes and changes its babies. My father was nineteen years older and in poor health. I can’t imagine his reactions if he could hear about the domestic duties of the ‘new man’.

I was usually left in the care of the cook or the housemaid and they competed to spoil me. The spoiling flagged when I didn’t want to go to bed and the poor girls wanted to go out and meet their boyfriends. Because of this, I was taught that, once in bed, it was wise to stay there for fear of bogey men. As well, I learned always to keep my hands under the sheets. This was to discourage thumb-sucking, I believe. I was told that the child who was foolhardy enough to leave so much as a finger out of bed might have it taken and shaken by an ice cold hand, while a menacing voice asked, ‘How are you keeping, this fine night, Miss Marjorie?’ It was years before I outgrew my fear of the phantom hand.

Sometimes, the maids tired of minding me, and let me run out to the yard and ‘help’ Danny or Edmund with the milking, or feeding the calves. As I lived in total isolation from other children, I didn’t miss their company and was perfectly happy most of the time. My parents were thirty-two and fifty when I was born, and I grew from a toddler to a little girl with a distinctly middle-aged view of life. I was four years old when I first saw a baby. I’d been told of the treat in store and imagined something like the toothlessly smiling infant sitting on a cushion on the tins of Allen & Hanbury’s rusks. I couldn’t wait. Nanny took me to our neighbour’s house, where the mother was busying herself in the kitchen with a basin, towels and soap. I looked around eagerly but saw no sign of a baby. A towel was spread on the table, and on it a small purplish red creature lay on its back, eyes screwed shut, fists in the air. My innocent question, ‘What is it? Is it cooked?’ earned me a stinging slap and a scolding. My yells woke the baby, who added his own, and I realized my hideous mistake.

Even then, I hardly believed I was looking at a human infant; one moreover who was called Francis Joseph and is now a retired schoolmaster. I wasn’t easily forgiven.

*

I went to hardly any parties. As for birthdays and Christmas, they were times for presents but not for outings. The presents were of three kinds: books, chocolates and money. The chocolates were hidden and doled out at a rate of two a day. The books were hidden too, until my mother had read them to make sure they were ‘suitable’. The money disappeared into the Post Office. I became adept at finding the chocolates and the books, which I read in the airing cupboard. But the Post Office beat me; it seemed an unfair place to hide presents as they never re-emerged. I hadn’t grasped the principles of saving and wouldn’t have been impressed by them if I had.

My chance to beat the system came when I was nine years old. My grandmother gave me two pounds for my birthday – actually put two green pound notes in my hand. ‘Get your mother to put it in the Post Office for you,’ she said.

My mother was going to Nenagh to have her hair done and took me with her. By then, the nannies had long gone and she often took me with her – not that she ever went very far herself. I was clutching my £2, so soon to disappear for ever. The hair-dresser was a patient lady called Miss Ryan, who needed all her patience when I exchanged Nanny for a governess who made me learn a hymn by heart every Sunday. When my mother took me with her, I sang these hymns to Miss Ryan, and my mother, deafened by the roaring dryer, didn’t know what was happening. As soon as she could get a word in, Miss Ryan would give me twopence and tell me to run up to Gleeson’s Fruit Shop and get an ice-cream.

On this momentous birthday, my mother went to a different salon, Hassey’s, in Barrack Street, where sales of pigs and calves took place. I wandered out and watched. The calves were in carts, drawn up on either side of the street, with the horses facing outwards. There were also pigs, whose deafening squeals filled the air as they were prodded and pulled about.

I walked along the row of carts, looking into each one, the money crumpled in my hand. A stout man in a raincoat asked, ‘Buy a calf, Miss?’

Buy a calf? Why not? With the Post Office waiting to swallow my money, it seemed a good idea. ‘How much is the roan one?’ I asked. The man asked £4, I craftily offered ten shillings. After spirited bargaining, in which at least a dozen bystanders joined, I bought it for £2 and the man spat on a threepenny bit and gave it to me for luck. I asked him to deliver the calf to my home, a distance of more than four miles. He agreed, reluctantly, urged on by my supporters. I think he was expecting to have to return the money and take the calf back. Instead, when he reached my home, he persuaded my father to buy the other calf, a white one which died almost at once.

I named my calf Polly, after my grandmother, but this was said to be cheeky, and her full name, Caroline, only slightly less so. I thought of the horse, Mr Minnitt, but I could hardly call my calf Mrs Smithwick, and Granny sounded wrong for a week-old heifer. I called her Starr in the end, after the man who sold her to me. Some time afterwards, my father sold Starr for £3 and put the money in the Post Office for me. This started in me a lifelong distrust of almost all financial institutions.

*

Although I became a horse dealer when I was still in my teens, when I was younger, horses were the only stock I never dreamed of selling. Our carthorses worked until they died or were pensioned off or put down. I loved them all and would have been deeply shocked if one of them had been sold. Cattle were a different matter and I was fascinated by the fairs which were held in the streets on the first Monday of every month. The noise, dirt and general chaos were profoundly appealing to a child kept in a nursery and bound by an unchanging routine.

The calf, pig and fowl markets were quieter and more civilized affairs, except at Christmas. Pig dealers, who could easily be recognized by their bowler hats and the way they wore their socks outside their trouser-bottoms, were considered to be farther down the social ladder than cattle or sheep dealers. At the Christmas market, pork pigs and kid goats were sold, as well as every kind of poultry.

Geese were more popular than turkeys in the country, and there was a great trade for them. They used to be sold wholesale to dealers who shipped them to Liverpool, then marched them across England in droves to Manchester, Leeds, York and even Newcastle. Geese are great walkers – fortunately – but their feet wouldn’t stand up to so much roadwork. Accordingly, at the port, they were driven first through soft tar, then through sand. After this treatment, they were as good as shod. No wonder Irish geese were more renowned for muscle than fat.

We never bought anything in the market except my calf. The turkey market was an uproarious affair, and got more so as the day progressed. Farmers’ wives had few opportunities to go to town, and for many, the turkeys were their only income. Fierce bargaining took place, and acrimonious arguments. I remember a grey-haired woman, tall, broad and determined, who wore a black hat rammed down on her head, a man’s black frieze coat and nailed boots. She could outshout any man in the market and outswear him too. She started a violent argument with a usually peaceable butcher, about the weight of a tremendous old cock turkey. The bird, feet tied, was clutched in her powerful arms, and its face and hers were alike red and furious. Bets were laid and a crowd gathered outside the butcher’s stall. The butcher lost his nerve and refused to weigh the turkey on the spring balance in his shop. Next door was a chemist’s shop with a wicker-basket scales for weighing babies. The woman charged into the shop and dumped the bird in the basket, where it turned the scales at forty pounds. She then marched out in triumph to collect her winnings, without a word to the scandalized chemist.

My parents avoided fairs and markets unless they had business there; neither could understand my fascination with them. I didn’t either, but I had a feeling of being in my real element. I wanted to buy and sell, and the noisy crowds didn’t bother me at all. I was a born dealer and it was lucky that, when I was young, I had no money to lose. I’m still dealing.

CHAPTER TWO

Family Glimpses

Elderly people are often accused of seeing the past through rose-tinted spectacles. I’m sure the reason for this is that my generation and the ones before were out of touch with reality. Unless you were starving, fighting in the trenches or doing social work, your vision was blinkered by lack of communication and by censorship. Television and the press now bring every aspect of crime, misery and vice to our sitting-rooms. No wonder that, as we grow older, the past seems rosier, the present gloomier.

The sun in those bygone days shone all through the summer (but not enough for the crops to fail), young people joyfully obeyed their elders, women were beautiful, men were brave and handsome, marriages were happy. Horses were plentiful and cheap; foxes were plentiful too, and ran tirelessly across the grass fields in the winter sunshine. There was no barbed wire hidden in the (neatly clipped) hedges, and the teller of the tale, if he is to be believed, was always well to the fore. He was never afraid, never fell off and his horse never went lame.

Most of this of course is untrue. I think we did have less rain. The spring which supplies my house with drinking water hasn’t run dry for many years but, when I was a child, we used to fetch water from Lough Derg every day in summer, in barrels. Yes, we drank the lake water. We boiled it but we drank it. Who would drink it now unless strained and pasteurized? We weren’t fussy. We knew that cattle stood flank-deep in the lake, keeping cool. Honest dirt, we said, never hurt anyone.

As for young people obeying their parents, I think they did. I accepted that my father’s word was law and seldom questioned my mother. It was many years before I started trying to escape from the way of life which had been chosen for me. Other young people were coerced into jobs they hated because of family tradition. This could lead to a whole lifetime of frustration and regret.

An extreme example at an earlier date was that of my father’s family. His father was a clergyman, so there was no land to be allocated. The eldest son was told to join the army, the second (my father) was earmarked for the navy, the third would (of course) enter the Church. No plans had been made for number four, who was much younger.

Uncle Charlie was killed in South Africa at seventeen by a Zulu spear and his body never recovered. My father, happily preparing to join the navy, was rerouted into the army. He was upset. He argued. But he went. A good rugby player, he told me that one of his worst moments ever was when he had been capped to play for Ireland, but sailed for South Africa instead, on the day of the match. Uncle Fritz was studying Divinity and was grudgingly allowed to continue and little Uncle Algy was steered early into the navy. He must have done all right as he got to be an admiral, but he said he only joined to please his mother.

His mother was granny – Granzie as the family called her – and few people argued with her. I remember her as an alarming old lady, tall, straight and bossy. ‘You’ll turn out just like your grandmother,’ was my mother’s worst threat. She may have had a point … Granzie, friend of Maud Gonne, Mrs Sheehy-Skeffington and other movers and shakers, chained herself to the railings in College Green and hurled women’s suffrage pamphlets over the balcony in the Gaiety. She loathed Bernard Shaw and had an incandescent correspondence with him, so I have been told. If only the letters had survived!

As Granzie told me how meek and obedient the children of her day had been, I wondered in my muddled way how this generation of slaves had grown into fearless, independent adults, such as Granzie herself. She was keen to go to prison to help the Suffragettes, but being the widow of the Chancellor of St Patrick’s, failed to realize her ambition. She championed all kinds of lost causes and was an ardent Nationalist and Republican. When she died, it turned out that she had lent money to many people, and been a loyal friend. She certainly never obeyed anyone.

*

Granzie’s mother was the last person born and reared at Bunratty Castle before the family abandoned it and built what is now the Bunratty House Hotel. I belong to the Smithwick family who first came to Ireland about six hundred years ago and have remained ever since. I dislike being classified as Anglo-Irish, but there seems to be no escape.

My Smithwick forbears originally settled in Wexford and Kilkenny, where some of them founded the noted brewery. John Smithwick, of the so-called ‘Protestant branch’, lived at Athassel Abbey House, near Golden in County Tipperary. Two hundred years ago, he had a lot of land, a lot of money and a son who inherited a tidy fortune. This John had six sons and built houses for all of them. One, Garrykennedy, was to be a three-storied affair, but the money ran out halfway up the stairs. They clapped a roof on, and all the gracious bedrooms have sloping ceilings. The largest house was Shanbally House Stud; the smallest was Crannagh, where I lived for much of my life.

The sons died young, or produced only daughters, as was so often the case in such families. Two generations later, I, the only child of the head of the family, was having a hard struggle to keep my home and land. Only a strong physique and a dislike of being beaten enabled me to do so.

My mother was born and grew up in England, but had many relations in Ireland: Russells, Coghills and Somervilles. She lived in Ireland for fifty years, but had never wanted to. She didn’t unpack her trunks for several years. She returned to England after I married – but only for two months. It had changed; she was glad to get back. We shared a home until she died and, twenty-one years later, I often miss her. She was such good company and the most loyal person I have ever known.

My father inherited Crannagh from his great uncle Robert, to his own delight and my mother’s horror. They moved here in 1929. (Fifty years to the day later, my mother died.) When they arrived, the place was run down to a degree. Uncle Robert was blind for many years before he died, and his daughter and son-in-law weren’t good farmers or even capable land-owners. My parents inherited, along with the farm, four men and four woman employees. As the house had been empty for several months and an inefficient cousin was ‘running’ the farm, it was somewhat over-staffed and under-financed.

The cook and housemaid were still there when I was old enough to ask questions and they told me some odd things. One was that Crannagh had been used as a ‘safe house’ by Michael Collins more than once during the Civil War, although this was strictly De Valera country. Another was that the family car, taken by raiders, was the original ‘Johnson’s Motor Car’ of a popular song of the time. Great Aunt Emmy, the last of the family to live at Crannagh before my parents, was adept at the art of burying her head in the sand, and not one word of these things ever reached my parents except what I learned and told them myself. ‘I don’t think we want to hear about that sort of thing,’ said my mother and her friends.

CHAPTER THREE

Horse Mad

When the Second World War broke out, Ireland was just recovering from a different kind of conflict – the Economic War. This was more of a deadlock than a war and, like most wars, was hardest on those who least deserved to suffer.

When De Valera came to power, he was intent on a self-sufficient rural community. He refused to pay the required annuities to England, and the British government retaliated by imposing heavy tariffs on Irish produce. Ireland then raised her own tariffs, and the result was a crash in prices, the wholesale slaughter of calves and the ruin of farmers who depended on the cattle trade for their living.

De Valera had wanted to transfer the cattle-dealers’ power, which was considerable, to tillage farmers, as tillage provided more employment than stock. Employment would cut down emigration, and small-holders would be able to survive. This was the general idea, but it didn’t work. Looking back over old account books, I read of bullocks bought at £14 each being sold a year later for £6. Calves were worth the price of their skins. We were lucky, having my father’s British army pension, which paid the wages and the housekeeping; others sold out to the Land Commission, becoming in effect tenants of the government. Young people emigrated in droves.

I can’t remember too much about it, being a small child at the time when things were worst, but a few memories remain. My father bought a small red and white heifer from an elderly widow, who had come to the house with a hard-luck story. He had been refusing to buy from half the countryside as he was believed (wrongly) to be wealthy. The farm was already overstocked, the bank manager getting peevish. When the woman, who was evidently desperate, explained that the heifer was all she had to keep her until harvest, my father gave her £5 for it, which was double its market value. Even so, she would have had no more than 10 shillings a week to live on until her acre of oats was fit to sell.

The heifer was very tame and I used later to ride on her back. We called her ‘the Widow’s Mite’. Unknown either to the widow or to us, the Mite was in calf, and produced a black heifer calf. So we kept her for a cow and a very bad one she was.

The worst of the Economic War had passed by 1934, but farming remained bad right up to the start of the Second World War, and cattle prices never really recovered until the seventies. I can remember the drovers who walked their cattle all day and slept at the side of the road at night, travelling from fair to fair. Some dealers could afford ‘hackney cars’ or taxis, but many walked their own beasts, about eight or ten miles a day in all weathers, selling as they went. In summer they put grass in their boots to keep their feet cool; on wet fair days they stood in the rain until the water ran out of their boots. Many of the drovers were ex-servicemen from the First World War, unable to survive on their pensions.

Constant wettings led to arthritis, rheumatism and TB. On the other hand, people on the whole grumbled less, and they certainly had fewer heart attacks.

*

Although I spent a lot of time with farm animals, I wasn’t encouraged to ride when I was small. I never owned what could be termed a child’s pony – not when I was small enough to ride one. Having started riding on Clydesdales, nearer seventeen hands than sixteen, I thought a pony a terrible comedown. Riding the carthorses bareback was something of a balancing feat, but otherwise easy. They responded to commands like sheepdogs. ‘Hup off’ or ‘Come in’ would turn them left or right. ‘Hup’ was for forwards, ‘Way’ for backwards and ‘Sight’ (or would it be ‘Site’?) for stop. I gave these orders in a loud gruff voice, and it took me years to break myself of saying ‘Sight’ to my hunter when I wanted it to stop.

Perhaps if a quiet pony had been provided for me, I would have been less determined to climb onto the back of any four-legged animal that would allow it. My father had inherited Andy and Dandy along with the farm. I was happy enough clumping around on their broad backs until I saw the foxhounds in full cry. Then I began to dream of speed and thrills and to beg for a pony. For years, I begged in vain.

I have a snapshot of myself on Fred, wearing a tidy jacket and a pair of pint-size jodhpurs, made by Mr Condon the tailor. (I remember sitting on his counter, drawing faces on somebody’s cut-out suit in tailor’s chalk.) My feet are in the stirrup leathers, because my legs are too short to reach the irons. I am profoundly happy. Then my mother shouts from an upstairs window, ‘Get that child a hat!’ She, of course, is picturing me being dragged by one of those stiff, curling stirrup leathers and probably killed; she means a hard hat.

I slide off Fred (it’s like sliding down a roof), run indoors and clap a hat on my head. To me at five years old, a hat is a hat. The one I am wearing in the snapshot is a broad-brimmed affair in yellow straw with a wreath of buttercups and satin bows.

When Fred died, I tried riding Packy, a black horse with a nasty temper from having been backed under heavy loads. He used to turn his head and snap at my toes with long, discoloured teeth. I begged and begged for a pony.

When I acquired Martin, a smart little roan, I thought he would be easier to ride than the carthorses because he was smaller. I was wrong. He was difficult to catch and, once caught, difficult to ride. Martin was only 13.2 hands, but he was a cob rather than a pony. He was a thickset roan with a mind of his own. The idea was that he would be useful on the farm when I had outgrown my passion for riding. He certainly did his best to cure me, usually by stopping dead and dropping his head. I would slide bumpily, head first down his bristly hogged mane, and Martin would tip me over his ears and trot away. I fell off him every time I rode him – sometimes several times – and he didn’t respond to any of my commands. In fact he was boss. I cried for hours when he was sold. I wonder why.

I was about eight when Martin was sold and I decided to ride something safer, namely either the Widow’s Mite or a red cow called Adelaide. I rode them in from the field at milking time, and both were far better schooled than Martin – although that wasn’t saying much.

I suppose I had a way with animals, because I had little trouble in taming and training the cattle. I never tried saddling one, but as soon as I was tall enough to get onto their backs I took to riding the bullocks round the fields. I made string halters for them and gave them names. One of my favourites was called Blue Peter after the Derby winner of that year.

My parents decided that such dedication deserved a better mount, and bought me an elderly black pony called Pippin. She had a hollow back which made a nice change. Cattle are not designed by nature for bareback riding. Pippin was more like a little hunter. I taught her tricks and played all sorts of games with her.

One of these needed my father’s help. I was the Flower of the French Cavalry or a Death’s Head Hussar, according to which war we were fighting; he was unshaken infantry. He knelt on one knee, aiming a shooting stick, and Pippin and I charged him. Pippin would sheer off at the last second and I, more often than not, fell off. I enjoyed these simple war games enormously, and began to improve on them. I invented one in which I cut the heads off thistles with a sword (a real one) while galloping bareback across a field.

This activity was discovered and stopped, but not before I’d fallen off several more times, usually on my head. It was lucky for me that only the thistles were decapitated. After that, my father taught me to fall on my feet like a cat. I started my falling-off lessons in the haybarn, tumbling off the patient Pippin backwards, forwards and sideways. Then I graduated to jumping off at every speed up to a gallop. It was great fun and I’m sure that it’s almost as important to learn how to fall off as how to stay on. In all the years I rode young horses, I never broke a bone, and my back injury was the result of a pitching headlong down a flight of marble stairs.

Because of these lessons, I wasn’t frightened of falling, so I seldom fell. I always landed on my feet unless the horse came down too, when I tucked my head in and rolled away. Old hands tried to scare me with tales of crucifying falls; of the ‘croppers’, ‘crowners’, and ‘vet and doctors’ they’d survived – just. I remained unimpressed and confident until my young horse caught his foot in a hidden strand of wire on a narrow bank. That day, I rode home wearing the brim of my bowler hat round my neck, in a sort of happy stupor. I don’t know why my head didn’t hurt. About a mile from my gate, I began to have grave doubts about my direction. I’m glad to say that my horse knew his way home, so I was spared the humiliation of asking a neighbour.

*

To return to the time when I got Pippin, I quickly became that familiar thing, a horse-mad child. I felt that all time not spent with ponies or horses was wasted. I remember, but can’t place, a verse I read years ago, which must have described the feelings of many parents, certainly my own:

I love my child – I like the horse –

But this is what is sad.

The two together, night and day,

Will drive me mad …

Always a voracious reader, I turned from the Waverley novels, through which I had been doggedly worrying my way, and read only ‘pony books’. This genre must have had its day – I don’t see many of them in the shops now. Probably girls of from ten to fourteen years old mostly read adult books, comics or teenage romances. In the forties, pony books were everywhere and I had a cupboard full of them in my room.

These works had titles like A Pony for Penelope, A Hunter forHenrietta, A Cob for Kate. They were never called A Gelding for Gideon or A Filly for Philip, because they weren’t written for boys. The children were always female, about twelve years old and spoiled rotten. The ponies on the other hand were usually male, about 13.2 and only partly spoiled. Penelope or Kate sorted them out in time to win the bending race in the last chapter.

The books were always illustrated, often beautifully, so that the not so well informed could see just what a bending race was. It suggests a gymnastic competition to the non-horsey.

I used to think that some day I would write a pony book of my own (A Mare for Marjorie), and I made several attempts to start one. The problem was that the books were written to a formula outside my experience. They were generally set in the Home Counties of England, where kind Mummies and Daddies bought ponies for their children as a matter of course. The Daddies, although generous, were uninterested. They spent their working hours in London offices and their leisure playing golf. The Mummies, once horsey little girls themselves, were more helpful.

Although the story lines were simple, the language was not. ‘Isn’t he a teeny bit overbent, darling?’ Mummy would enquire anxiously (all those bending races). Or ‘Do be careful, Samantha, Topper’s getting behind his bit.’

Where else could a pony be in relation to his bit except behind it? I wondered. Ahead of it? Surely not.

The books were always full of instructions about riding and stable management; sometimes sound, sometimes not. I learned a good deal. Some of the terms defeated me and it was no good asking my father, who despised the books heartily. I asked a friend to translate Samantha’s request, ‘Mummy, shall I give Topper a direct aid?’ and Mummy’s solemn reply, ‘Very well, darling. Just this once.’

‘A direct aid’s a crack down the ribs with an ashplant,’ said my foxhunting friend. I filed this information away, wondering why Samantha couldn’t be more explicit.