6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

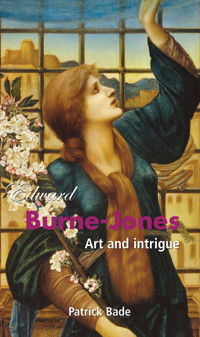

Burne-Jones’ oeuvre can be understood as an attempt to create in paint a world of perfect beauty, as far removed from the Birmingham of his youth as possible. At that time Birmingham was a byword for the dire effects of unregulated capitalism – a booming, industrial conglomeration of unimaginable ugliness and squalor. The two great French symbolist painters, Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, immediately recognised Burne-Jones as an artistic fellow traveller. But, it is very unlikely that Burne-Jones would have accepted or even, perhaps, have understood the label of ‘symbolist’. Yet he seems to have been one of the most representative figures of the symbolist movement and of that pervasive mood termed “fin-de-siecle”. Burne-Jones is usually labelled as a Pre-Raphaelite. In fact he was never a member of the Brotherhood formed in 1848. Burne-Jones’ brand of Pre-Raphaelitism derives not from Hunt and Millais but from Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Burne-Jones’ work in the late 1850s is, moreover, closely based on Rossetti’s style. His feminine ideal is also taken from that of Rossetti, with abundant hair, prominent chins, columnar necks and androgynous bodies hidden by copious medieval gowns. The prominent chins remain a striking feature of both artists’ depictions of women. From the 1860s their ideal types diverge. As Rossetti’s women balloon into ever more fleshy opulence, Burne-Jones’ women become more virginal and ethereal to the point where, in some of the last pictures, the women look anorexic. In the early 1870s Burne-Jones painted several mythical or legendary pictures in which he seems to have been trying to exorcise the traumas of his celebrated affair with Mary Zambaco. No living British painter between Constable and Bacon enjoyed the kind of international acclaim that Burne-Jones was accorded in the early 1890s. This great reputation began to slip in the latter half of the decade, however, and it plummeted after 1900 with the triumph of Modernism. With hindsight we can see this flatness and the turning away from narrative as characteristic of early Modernism and the first hesitant steps towards Abstraction. It is not as odd at it seems that Kandinsky cited Rossetti and Burne-Jones as forerunners of Abstraction in his book, “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 47

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Author: Patrick Bade

Layout: Baseline Co Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan

4thFloor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City,

Vietnam.

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Patrick Bade

TABLE OF CONTENT

1. King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid, 1880-1884

2 .The Annunciation (“ The Flower of God”), 1863

1. King Cophetua and theBeggar Maid, 1880-1884.

Oil on canvas, 290 x 136 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

When Burne-Jones’ mural sized canvas ofKing Cophetua and the Beggar Maid(p.4) was exhibited in the shadow of the newly constructed Eiffel Tower at the Paris Exposition universelle in 1889, it caused a sensation scarcely less extraordinary than the tower itself. Burne-Jones was awarded not only a gold medal at the exhibition but also the cross of the Légion d’honneur. He became one of those rare “Anglo-Saxons” who, from Constable in the early nineteenth century to Jerry Lewis in the late twentieth century, have been taken into the hearts of the French intelligentsia. For a few years while the Burne-Jones craze lasted, fashionable French women dressed and comported themselves “à la Burne-Jones”, cultivating pale complexions, bruised eyes and an air of unhealthy exhaustion. The two great French Symbolist painters Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes immediately recognised Burne-Jones as an artistic fellow traveller. In 1892, the cheer leader of the “Decadence” “Sâr” Joséphin Péladan, announced that Burne-Jones would be exhibiting at his newly launched SymbolistSalon de la Rose-Croixalongside Puvis de Chavannes and other leading French Symbolist and English Pre-Raphaelites.

Burne-Jones wrote to his fellow artist George Frederick Watts “I don’t know about the Salon of the Rose-Cross — a funny high-fallutin’ sort of pamphlet has reached me — a letter asking me to exhibit there, but I feel suspicious of it.” Like Puvis de Chavannes (who went so far as to write toLe Figarodenying any connection with the new Salon), Burne-Jones turned down the invitation.

It is very unlikely that Burne-Jones would have accepted, or perhaps even have understood, the label of “Symbolist”. Yet, to our eyes, he seems to have been one of the most representative figures of the Symbolist movement and of that pervasive mood termed “fin de siècle”.

Symbolism was a late-nineteenth-century reaction to the positivist philosophy that had dominated the mid-century. It found expression in the gross materiality of the paintings of Courbet and Manet and the realist novels of Emile Zola and in Impressionism with its emphasis on sensory perception. Above all, it was a reaction against the belief in progress and modernity represented by the Eiffel Tower itself and against the triumph of industry and commerce celebrated in the vast “Hall of Machines” in the same exhibition, which had filled Puvis de Chavannes with horror and had given him nightmares.

2 .The Annunciation (“ The Flower of God”), 1863.

Watercolour and gouache, 61 x 53.3 cm.

Collection Lord Lloyd-Webber.

3. Sidonia von Bork, 1860.

Watercolour and gouache,

33 x 17 cm. Tate Britain, London.

Burne-Jones’ entire life’s work can be understood as an attempt to create in paint a world of perfect beauty, as unlike the Birmingham of his youth as possible. When Burne-Jones was born in Birmingham in 1831, it was known as the “workshop of the world”. Before the exemplary reforms of Mayor Joseph Chamberlain in the late nineteenth century, Birmingham was a byword for the dire effects of unregulated capitalism — a booming, industrial conglomeration of unimaginable ugliness and squalor. The sense of anxiety and alienation that pervades much of Burne-Jones’ work and that, despite his yearning for the distant past makes him seem so modern, goes back to his earliest childhood experiences. Like Munch, he could have claimed that sickness and death were the dark angels watching over his cradle.

His mother died within days of his birth and, though his father was later affectionate and caring, he could not at first bring himself to touch or even look at the child who reminded him of his grief. Burne-Jones (or simply Ned Jones, as he was known at this period of his life) grew up a sickly child. According to his wife Georgiana (Georgie), constitutional weakness “must take its place as one of the understood influences of his life”. She tells us how later in life he might be found “quietly fainting on a sofa in a room where he had been left alone”. This weakness was as much psychological as physical. According to Georgie, “with him, as with sensitive natures, body and mind acted and reacted on each other”. “He could never rid himself of apprehension in life … and was at times worn out by the struggle to meet and endure troubles that never came as well as those that did’. Even more than his elaborately wrought paintings, Burne-Jones’ humorous drawings, made for the amusement of his friends, reveal the terrors of his inner life with startling frankness.

4. Going to the Battle, 1858.

Grey pen and ink drawing on

vellum paper, 22.5 x 19.5 cm.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

5. Clara von Bork