Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

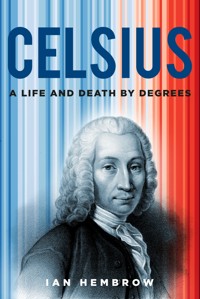

The Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius (1701–44) was arguably the world's first true Earth scientist. In Celsius: A Life and Death by Degrees, Ian Hembrow reveals what his extraordinary, but tragically short, life and career can teach us about our today and humanity's tomorrow. Our modern understanding of many of the Earth's most awe-inspiring phenomena owes much to a modest and quietly spoken, eighteenth-century Swedish astronomer, who died of tuberculosis aged just 42. From the Northern Lights, air pressure and magnetism to the shape of the planet, sea levels and early studies of climate change, Celsius unravelled some of the greatest mysteries of his time. Best known for inventing the 100-point 'centi-grade' scale, Celsius' name also now frames humanity's future in the international targets to limit average global temperature increases to no more than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. As our world faces this life-or-death struggle, there's much we can learn from Celsius – if we will listen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 416

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Celsius: A Life and Death by Degrees

‘From my home in Canada, where 'fire' is now a season, I read Celsius to learn about the man whose name signals both threat and comfort. What I found was a life fuelled by insatiable curiosity and an ability to wonder – much needed qualities as we face today's polycrisis. This biography reveals the human capacity to seek answers, even when, as Celsius writes: 'the process of discovery has no end’. This is an important book for our time.’

KATE ELLIOTT

Simon Fraser University

Vancouver

‘This book gives readers a much broader perspective on the life of Anders Celsius and his diverse scientific work and discoveries. The story takes us deep into the world where his experimental measurements in Lapland with Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis showed how Newton's universal law of gravitation literally shapes our planet. It was a breakthrough that forged the later lives and fortunes of both men, and forever changed the way humanity perceives its home.’

Veli-Markku Korteniemi

Chairman of the Maupertuis Foundation

Finland

‘This is a beautifully written masterwork of science biography, covering the life and times of the great Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius. Ian Hembrow provides a gripping narrative that details his search for a man who was very much embedded in his city and landscape, who now remains relatively obscure even though he left an indelible mark above and beyond his invention of the Celsius temperature scale. This biography not only sheds light on a brilliant polymath and the colorful world of eighteenth-century science and its many characters; it also raises larger and more contemporary questions around global warming and the relevance of Celsius to the world we live in today.’

Dr Sarah Covington

Professor of History, Biography and Memoir

City University of New York

Front cover image: Etching of Anders Celsius c. 1730 by an unknown artist, and Ed Hawkins’ warming stripes, University of Reading, 2024.

Back cover image: Portrait of Anders Celsius c. 1730 by Olof Arenius.

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ian Hembrow, 2024

The right of Ian Hembrow to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 462 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

This book is dedicated to Martin Ekman, associate lecturer at Uppsala University – a friend and scientist who carries his knowledge and wisdom lightly, and who has done so much to keep the name, achievements and personality of Anders Celsius alive for the twenty-first century.

It is easy for us to stand outside, our face to the wind, and not realize that once upon a time we had no name, nor understanding of what wind was.1

Carl Leonard

1.5°C is not a goal or target, it is a biophysical limit. Cross it, and we are likely to trigger multiple tipping points in the Earth system. There is no safe landing for humanity, with regards to a manageable climate, unless we also bend the curves and return back to a safe operating space within planetary boundaries, for land, water, biogeochemical flows and biodiversity.2

Professor Dr Johan Rockström

Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon and the truth.3

Attrib. Buddha (c. 563–483 BCE)

CONTENTS

Foreword

Prologue

Charts and Maps

Anders Celsius’ Timeline

PART I: FIRE

1 Risen from the Sea: The Land from Which Celsius Came and Where he Rests Among Kings

2 Forged in Flames: The Origin Story of Celsius the Scientist (1701–02)

3 A City of Learning: Uppsala and Sweden’s Age of Freedom (1720–72)

4 A Family of Ambition: The Celsius Name and Prominent Ancestors

5 A Frustrated Father: Nils Celsius and his Ruinous Dispute with the Church of Sweden

6 The Age of Enlightenment: Young Celsius and Science in Eighteenth-Century Europe (1710–19)

PART II: LIGHT AND AIR

7 The Young Professor: Establishing his Roles and Reputation in Uppsala (1719–32)

8 Celsius’ Grand Tour: Learning from Europe’s Great Astronomers and Observatories

9 Two Countries, Four Sisters: Travels and Studies in Germany and Italy (1732–34)

10 In Paris: Encounters, Observations and Opportunity (1734–35)

11 In London: Appreciation, Trust, Recognition and Craftsmanship (1735–36)

PART III: LAND

12 Towards the Pole: The French King’s Arctic Expedition Led by de Maupertuis (1736–37)

13 Arctic Summer: The Torne Valley, Instruments and Triangulation

14 Arctic Winter: Ice, Measurement and Calculation

15 Fighting for the Truth: Conflict and Controversy (1737–40)

PART IV: SEA AND SPACE

16 Serving and Observing: Uppsala’s First Observatory (1741)

17 A Vast, Profound Truth: Unravelling the Baltic Sea Mystery (1741–43)

18 The Infinite and the Invisible: Magnetism and Making Connections (1740–43)

PART V: TEMPERATURE AND CLIMATE

19 One Hundred Steps: Creating the Centigrade Scale (1741–43)

20 Death of a Star: Celsius’ Illness and Death (1743–44)

21 Noble Successors: How Wargentin, Hiorter, Strömer and Others Continued Celsius’ Work

PART VI: TIME

22 A Safe and Just Earth for All: Celsius’ Legacy, Our Indifferent Planet and Hope

Epilogue

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

FOREWORD

By Anna Rutgersson, Professor of Meteorology, University of Uppsala, Sweden

In 1722, 20-year-old Anders Celsius and his professor Eric Burman began making temperature observations at the university in the old centre of Uppsala. These still continue today at my department nearby.

Three hundred years after these first measurements, we held a celebration conference to mark the tricentenary of this important milestone in science. During the event, I tried to picture what weather and climate observations would be like in another 300 years’ time. But my imagination failed.

As professor of meteorology at Uppsala University, I’ve built my career to a large extent on understanding the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans. My research into air-water interaction and exchange, atmospheric turbulence, heat, humidity and greenhouse gases relies on systems and methods that test the limits of what it’s possible to do with high-quality data in the field. As such, I feel connected to my famous predecessor Anders Celsius.

Some of the things he did and explored are obvious to us now, some were probably wrong, and others left us with new knowledge that continues to shape our modern lives. This is why he and his work are still remembered, and why he remains so important.

Celsius was driven by a wish to understand and describe the world that surrounded him. It’s a curiosity that I try to keep in my own line of work and hope to inspire my students with. Celsius was well liked and very humble, but 300 years later, we still use his name every day.

My first contact with Ian, as author of this book, was around the time of the ‘Celsius 300’ celebration in 2022. He later spent time with my colleague, Professor Tom Stevens, and others exploring the city, story and legacy of Anders Celsius. I was impressed by Ian’s enthusiasm to discover more about Celsius the man, the life he lived and how the city of Uppsala formed his character.

There are a few other books and sources of information about Anders Celsius and his work, but the engaging way his relevance for science and society today are brought to life in these pages is truly fascinating. We get to follow Ian’s footsteps as he traces those of Anders Celsius, helping us to know the book’s subject as a person and as a scientist, whose busy career gives us a window into life in Uppsala and beyond in the first half of the eighteenth century. We learn that there was much more to Celsius than the name he gave to the scale we use when measuring temperature.

Celsius gives us a perspective on the great challenges of today, when we more than ever realise the need to understand our surroundings and changes to the global climate and environment from the perspective of human-induced impact. We cannot prepare effectively for the future if we do not seek to observe and understand the past and present. This book helps readers to do that, be they scientists, historians or anyone with an interest in the world around them and their place in it.

I echo Anders Celsius’ wish that humanity’s curiosity, discovery and science can be focused upon fulfilling our brief destiny, so that we may pass on this wonderful Earth alive and untrammelled to those who follow us.

Anna Rutgersson

Geocentrum, Uppsala,

Spring 2024

PROLOGUE

IN SEARCH OF TRUTH

‘That’s where Professor Celsius worked,’ said my companion Ralph, pointing to a squat, old, yellow and white building in the busy pedestrianised shopping street.

‘What, Celsius … as in centigrade?’ I asked, halting in my stride.

‘Yes.’

‘Wow!’

This is how my search for Celsius and fascination with his influence began. It was my first visit to the pretty Swedish university city of Uppsala. I’d been commissioned to write a book about the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Centre for Drug Monitoring there, and my host, the Englishman Professor Ralph Edwards, had taken me out for a lunchtime stroll. We walked up a steep path to the salmon pink castle, the high walls and twin domes of which dominate the city’s skyline. From there, we descended to crunch across the gravel of the flawless botanical garden dedicated to Uppsala’s famous scientific son, the taxonomist Carl Linnaeus (1707–78), and then wound our way back into the modern city centre, where we now stood in the pedestrianised shopping street of Svartbäcksgatan.

The building in front of us, which had brought me to such a sudden, standing stop was Scandinavia’s first purpose-built astronomical observatory, created here in 1741 by another of the city’s and country’s most notable Enlightenment figures, Anders Celsius. For some reason, the mention of this person’s name, in that place, at that moment, sent a tingle through my whole body. I felt connected to something urgent and important.

So this was where Celsius, the man whose name – now enshrined in the internationally agreed targets to tackle global climate change, which frame the whole future of humanity1 – went about his business. This was where he scanned the skies, observed the stars and invented his eponymous temperature scale. I knew that the painfully negotiated United Nations agreements were all about limiting future average temperature rises to just a few degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. But what else did I know about this familiar name and the scientist behind it? Like most people, I realised, very little. But, in that instant, I was seized by a desire to discover more.

I didn’t have to wait long. A short distance along the street we encountered a more-than-life-size bronze statue of Anders Celsius. For a man who lived in the first half of the eighteenth century, it’s a curiously modern and figurative depiction. He stands slim and erect, gazing to the heavens with a sextant raised in his outstretched left hand and a long bulb thermometer in his right. The stylised tails of a periwig and long frock coat splay out behind him, and he perches on top of a tapering, tiered arrangement of spouts and spheres that once cascaded with water, but then lay dusty and dry. I wondered if this was an ominous, if unintentional, visual metaphor for the state of our planet. At the bottom of the sculpture is a beachball-sized Earth globe – its key meridians and lines of latitude cast in the dark metal.

Apart from a perky, upturned nose, the statue has no facial features and few other surface details. But it immediately suggests a sprightly, confident and gracious young man – an enquiring mind and energetic spirit. Unlike many statues, this figure seemed to have life and personality, and it set me thinking: what could this long-dead person tell me about my life today, and the future prospects for humanity? What should we be aware of every time we use his name? And what might we learn from him, his work and the time in which he lived?

This book tells how Anders Celsius progressed from child to man, and from bright student to a fully fledged scientific great, whose career was cut tragically short. It examines who and what he became, and how the city and landscape where he spent most of his life shaped him. It also traces my own journey to follow in his footsteps and establish his lasting relevance. It seeks to rescue Celsius the man from obscurity and restore him to his rightful place among the best-known names of science and history.

In the months that followed, and on subsequent visits to Uppsala and other parts of Sweden, I learned more about Celsius. I discovered that he came from an illustrious family line of Swedish astronomers and mathematicians, and that he died from tuberculosis in 1744 when he was just 42. I also found out that his achievements extended far beyond inventing the temperature scale that defines most people’s knowledge. In fact, his work on thermometry came right at the end of his life, a footnote to a far broader career.

Anders Celsius was, I rapidly came to recognise, a theorist and practitioner of extraordinary range and long-term vision: a master of not just astronomy, but the whole realm of natural philosophy – mathematics, geophysics, geodesy – and a multilingual pioneer of measurement, data and analysis. Celsius was arguably the father of all climatology and Earth sciences. His life and work stand at the confluence of an astounding rollcall of the most influential European thinkers and leaders – from French and Swedish royalty to Pope Clement XII, Voltaire, Descartes, Newton and the Cassinis. Among scientific giants, his star and the constellation of his collaborators shone particularly bright.

As the layers of this mercurial man and his life were revealed to me, I began to wonder what Celsius would make of our species in the twenty-first century. What might he think about humanity’s slow awakening to its destructive habits and the overdue efforts to reduce or reverse our impact upon the fleck of space we call home? I imagined that he would see this not as a problem of science or nature, but as a problem of humankind, and one that only we can resolve.

By telling Celsius’ story I’ve sought to explore these questions and suggest answers to some of them. At the dawn of the Anthropocene Age, the effects of human-induced global warming are fast outstripping the planet’s natural ability to heal itself. And the Homo sapiens species stands incontrovertibly answerable for an accelerating mass extinction of thousands of other organisms. The United Nations estimates that around 150 species now become extinct every day.2 Against this backdrop, what can, should or must we learn from the curiously forgotten Anders Celsius?

From my research into his life and from following his path across Europe’s cities and into the frozen beauty beyond the Arctic Circle, I’m convinced that the quiet Uppsala scholar still has much to teach us. These lessons come not just from his trailblazing methods and breakthrough discoveries, but also his patient manner, his courtesy and deep-rooted instincts for international collaboration and long-term improvement.

In an academic career lasting barely two decades, Celsius was able to peer through the narrow aperture of his present to see and understand both past and future aeons in their true context. He recognised the universal forces that shape our world, and grasped the opportunities and obligations that rest with humans during our fleeting presence. Like his statue in Uppsala’s Svartbäcksgatan, he stood on top of the world, and he gave his life to bequeath better knowledge to later generations. The key question for us, three centuries after his death, is: are we inclined to look, listen and take heed of these messages from the past?

The observatory building where Ralph and I stopped stands at a diagonal to the modern street, its sharp corners interrupting the line of otherwise flat, modern frontages. This is because it pre-dates the last of several fires that consumed much of the old city. Each time Uppsala burnt down and was rebuilt, the street pattern altered, reflecting perhaps the citizens’ desire for a new start. So Celsius’ edifice stands slightly askew – the road’s only evidence of a medieval urban layout lost to merciless flames and heat.

The building’s appearance suggests something of its creator too – a man who stood together yet aside from others, a modest but prominent scientist, simultaneously self-effacing and high achieving. He was able to perceive things his predecessors and contemporaries could not, and his impact still reverberates.

Celsius was an immensely practical scientist: an accomplished craftsman, draughtsman, technician and administrator, as well as a theorist. He was devoted to exhaustive, empirical observation and experiment in search of fundamental truths. And he embodied the new mood and style of the European Enlightenment – a quest to comprehend the elemental drivers of creation, and humanity’s place within it.

Today’s thinkers, strategists, decision-makers and opinion-formers face the same questions. How and where do we stand on Earth, in our solar system and the universe? If, as history and current circumstances would suggest, humans are hardwired towards expansion, dominance, conflict and consumption, how can we continue to thrive and survive within a largely sealed system of finite resources? And how are we obligated to act, now that we’re aware of the damage we’ve already wrought and continue to inflict? If it’s already too late to save ourselves, do we have any higher responsibility for the continuance and well-being of our planet? To whom or what, if at all, are we accountable?

If today’s humans are as enlightened, informed and inventive as we so often assert, we will do well to look back into the life and accomplishments of Anders Celsius. Encoded within his methods, his feats, his character and the clues he left behind are some of the answers we seek. I hope that, from knowing more about this exceptional scientist, readers will gain some fresh perspective on contemporary dilemmas. And I believe that adopting a fresh outlook is a first step towards positive empowerment, agency and choices.

As the twentieth-century geochemist and guru of global warming, Professor Wallace Broecker, said: ‘The Earth’s climate is an angry beast, and we’re poking it with sticks.’3 Humanity needs to stop goading and seeking to dominate this creature, and find peaceable ways to live with it.

Even without the significance of his work for modern-day concerns, Celsius’ tale is captivating. From narrowly escaping death as a six-month-old baby in the 1702 Great Fire of Uppsala, to his four-year, shoestring-budget Grand Tour of Europe, then helping to prove the shape of the Earth through life-shortening hardship in the frozen far north, he practised science at the extremes. Celsius descended deep mines and climbed high towers to study air pressure, studied distant stars, galaxies and the Northern Lights, contributed to unravelling the mystery of apparently falling sea levels in the Baltic Sea and standardised temperature measurement using the boiling point of water and melting point of ice. By stepping into these extremes he was able to interpret and explain what lay between – the timeless actions of gravity, radiation, magnetism, tides, tectonics, vulcanism, geology, weather and waves that form our ever-changing environment.

The account presented here focuses on real people, places and events. Celsius, his peers, collaborators and successors left behind a hoard of written and physical material – not least his original 1741 thermometer and other custom-built instruments, plus an extensive library of books and correspondence. But there are gaps, so some details of Celsius’ motivations, conversations and emotions are necessarily speculative, based on knowledge of his relationships, traits and the norms of the time.

I’m a storyteller, and humanity needs stories now more than ever before. The ones we discover and tell each other about history and the present can point the path ahead to our future. And to influence it in the right ways we need to imagine that future. Stories are the way we motivate ourselves and mobilise each other to effect change. As a fellow writer said to me while I was working on this book: ‘All stories are true. Stories are sticky; stories are compelling; stories work.’

A world without Anders Celsius and his polymathic achievements would be less enlightened, less connected and less able to provide a sustainable future for its human and other inhabitants. It’s time for us to get to know and learn from this charismatic young man.

CHARTS AND MAPS

i Anders Celsius’ Family Tree

ii Celsius’ Sweden (Shown on Modern Borders)

iii Celsius’ Uppsala

Anders Celsius’ Uppsala (shown on 1702 map before the Great Fire).

iv Celsius’ European Tour 1732–37

Map created by Julie Kilburn.

ANDERS CELSIUS’ TIMELINE

1701

Born in Uppsala, Sweden

1702

Family home destroyed in the Great Fire of Uppsala

1714

Began studies in law

1717

Switched to private tuition in mathematics from Anders Gabriel Duhre

1719

Began astronomy studies, taught by his father, Nils Celsius, and Eric Burman

1722

Started work as an unpaid astronomy assistant atUppsala University

Began systematic recording of weather data withEric Burman

1724

Appointed as assistant to the Swedish Royal Societyof Sciences

Air pressure experiments reported by the Royal Societyin London

1725

Appointed as secretary to the Swedish Royal Societyof Sciences

1728

Deputised for Samuel Klingenstierna as Uppsala’sprofessor of mathematics

1730

Appointed as professor of astronomy after EricBurman’s death

1731

Started studies of Baltic Sea levels

1732

Began scientific Grand Tour to northern Germany

1733

Continued Grand Tour through southern Germanyand Italy

Published observations of the Northern Lights

1734–35

At l’Académie des Sciences in Paris with Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis

1735–36

In London, including time with Sir Edmond Halley at Greenwich Royal Observatory

1736

Returned to France to join de Maupertuis’ expedition to the Arctic

1737

Returned from the Arctic and awarded a lifetime pension by King Louis XV

Resumed role as secretary to the Royal Society of Sciences

Built a private observatory in his mother’s gardenin Uppsala

1739–41

Campaigned for and built Uppsala University’s firstastronomical observatory in Svartbäcksgatan

1740

Resumed studies of the Northern Lights and magnetism

1741

First recorded use of the Celsius temperature scale

1743

Resumed studies of Baltic Sea levels

Appointed rector of Uppsala University

1744

Comet observations

Died of tuberculosis and buried in the family tomb at Gamla Uppsala

1948

Degrees Celsius adopted as the International Practical Temperature Scale

2015

United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) Paris Agreement to hold ‘the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels’ and pursue efforts ‘to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’

2023

World’s hottest year on record

United Nations Global Stocktake, key finding 4:‘Global emissions are not in line with modelled global mitigation pathways consistent with the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement, and there is a rapidly narrowing window to raise ambition and implement existing commitments in order to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels’

PART I

FIRE

1

RISEN FROM THE SEA

The Land from Which Celsius Came and Where he Rests Among Kings

What lies behind us and what lies ahead of us are tiny matters compared to what lives within us.

Attrib. Ralph Waldo Emerson

His body is hidden beneath the red carpet in the knave of the small parish church at Gamla (Old) Uppsala in southern Sweden. This is where Anders Celsius lies alongside his illustrious grandfather Magnus and unlucky father Nils. The outline of the family tombstone is clearly visible, a rectangular depression in the weave. I lifted the edge of the carpet to see a corner of the slab sealing the crypt, polished like pewter by countless feet. The youngest man who lies beneath is familiar yet concealed, close but little known.

High on the wall up to my left, a black marble plaque, carved with pale-gold Latin capitals reads (when translated):

CLEAR SENSE, HONEST WILL,CAREFUL WORK AND USEFUL LEARNINGMAY HIS BONES REST IN PEACE AS SAFELYAS HIS REPUTATION WILL NEVER REST.

The Celsius family line ended with Anders and his premature death in 1744 from tuberculosis. He did not marry or have children, but his legacy persists. Three centuries on, the adventures, discoveries and methods of this restless polymath still influence the rhythms of our daily lives, and his name now carries the prospects for humankind.

The memorial plaque to Anders Celsius at Gamla Uppsala church in Sweden. (Courtesy of Dr Stephen Burt)

Gamla Uppsala is in the heart of the Uppland region, a few kilometres north of modern Uppsala. A visit here involves just a short drive through serene suburbs. All seems calm now, but this is a landscape transformed over millennia by natural forces of immense power. And all around the church are the massive and brooding grass-covered burial mounds of the Svea monarchs, the tribal warlords of this part of Scandinavia. Celsius was born, lived, worked and died close to here, and it was his observations on the Baltic coast to the east that helped to untangle the mystery of how and why Uppland rose from the water.

It was the sea that brought the first people to Uppland around 5000 BCE. The early settlers were sustained by a plentiful supply of fish and the serrated coastline’s myriad inlets, which steadily silted up with heavy clay to provide rich pasture and fertile farming land. Today, the gravel surfaces of graves surrounding the church are artistically raked into neat lines and swirls. Their modern appearance gives little clue to the site’s significance in the region’s history as the home of ancient pagan kings. Although, in one corner, an eleventh-century rune stone once used as an altar now forms part of the church’s outside wall. Its Viking-era carving of a horned serpent commemorates ‘Sigviðr, a traveller to England’ – an augury of Celsius’ own journey to England 700 years later.

Long before the Vikings, in the third century CE, it is believed that a grand, gold-adorned temple stood here, dedicated to the three great Norse gods: Odin the All-Father, Thor the thunder-god and Frey, the god of fertility. Every nine years during the month of Goi (mid-February to mid-March) folklore tells of the temple becoming the centre of intense worship and bloody sacrifice. Two male animals – rams, goats, boars and cockerels – were slaughtered each day during nine days of feasting, with one unlucky man also put to death alongside each pair. The bodies, both animal and human, were then strung up in a shady grove next to the temple, their slow putrefaction believed to confer holy blessings upon the trees from which they hung.

The land surrounding the village was also the scene of extravagant, ceremonial ship burials. The mounds that stretch out in all directions from the little church contain the graves of powerful chieftains, many of them buried in wooden longboats. The bodies were laid out on furs and festooned with jewels, pets and provisions: everything they would need for their journey into the afterlife. And later, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Royal Mounds formed a grand temple amphitheatre for skeid – carousing festivals with stallion races and more mass animal sacrifices.

Woodcut of the temple at Gamla Uppsala from Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (1555) by Olaus Magnus, which perfectly fitted the vision of this once being the capital of Atlantis. A golden chain winds around the building, with a human sacrifice in the spring to the right.

A 1709 map of Gamla Uppsala by Truls Arvidsson, showing some of the hundreds of burial mounds that surround the church and its Celsius family tomb.

With so much gore and drama soaked into this land, it is perhaps not so surprising that Olof Rudbeck the Elder (Uppsala’s seventeenth-century ‘universal genius’ of medicine, mathematics, astronomy, botany, chemistry, physics, natural history, gothic myth, art, engineering, mechanics, archaeology and architecture) speculated that this spot was once the epicentre of the lost continent of Atlantis. To prove this theory – to his own satisfaction, if few others’ – Rudbeck found linguistic, narrative and topographical evidence wherever he looked. This was, he suggested, the true home of the Hyperborean people of Greek mythology: a sunny, temperate and divinely blessed land beyond the north wind.

Whether Rudbeck’s claims in his 1675 opus Atlantica1 stand up to scrutiny or not, Celsius and his ancestors undeniably rest at a unique meeting point of history, myth and legend. The breeze that stirs the trees surrounding Gamla Uppsala church still seems to carry whispered echoes of the human struggle to claim this landscape from the cold Nordic Sea. The passage of time so evident here is also the perfect leitmotif for Celsius’ life and scientific method. He took the long view in everything he did, able to wrench off the blinkers of the present to see and understand the world around him in its true context of ages long past and yet to come.

Olof Rudbeck the Elder (1630–1702) – the eccentric ‘universal genius’ of Celsius’ home city and university in Uppsala. This illustration from his 1689 book Atlantica depicts him revealing Scandinavia’s underworld, surrounded by classical figures including Plato, Aristotle, Odysseus, Ptolemy, Plutarch and Orpheus.

Throughout his career, Celsius’ sights were fixed upon how his work could practically benefit humanity in the years that followed. In his 1733 account of observing the Northern Lights across Europe, he wrote: ‘It will bestow on our century a greater honour to have left true observations to later generations, rather than false hypotheses which can easily be refuted.’2

In geological terms, Uppland was underwater until quite recently. During the Neolithic period (4500–1900 BCE), the sea level was effectively 30 metres higher than today. And when the Vikings lived here (800–1050 CE), it was still some 7 metres higher. Waves once lapped the boulders surrounding the burial mounds now far inland, making it possible for heavy, clinker-built boats to be hauled ashore and entombed with the revered owners and their riches, beneath the man-made hills.

A Viking ship passing burial mounds on the River Fyris. Drawing by Olof Thunman.

Today, standing slightly apart from the church, an angular wooden bell tower juts dramatically towards the heavens, its shuttered openings and shingle-covered shape evoking a gigantic, armour-clad warrior. Coated in the region’s distinctive, iron red falu rödfärg paint and the petrified pitch of many decades, the tower looks out over the curving chain of burial mounds: a glowering sentinel silently registering the passage of generations.

As I followed the twisting path between the mounds, I pondered Celsius’ contribution to solving the riddle of this upsprung place. It was a profound, slowly unfolding truth that occupied half of his working life. The natural history that Celsius helped to reveal about his homeland was the perfect example of his experimental dexterity, daring imagination and urge to collaborate. His sharp eyes and singular mind seized upon the dynamic nature of the universe and our place within it.

From the top of the Högåsen ridge of burial mounds, I had an uninterrupted view across bright yellow fields of rape to Uppsala, a few kilometres away, its sixteenth-century castle and the tapering shards of the cathedral’s towers standing out in stark silhouette. It was at the university there that Celsius became recognised as a thinker of rare originality, there that he built up the reputation that saw him welcomed in the great European centres of his age to study eclipses of the sun and the aurora borealis. And it was to Uppsala that he returned in 1737, after the Arctic expedition that brought him to prominence and financial security.

In his final years, Celsius established Sweden’s first astronomical observatory in the centre of Uppsala, where he assembled a powerful coterie of skilled disciples and made further, revolutionary discoveries about the nature of light, temperature and the Earth’s magnetic field. He was a man in obsessive pursuit of primal principles, a relentless empiricist for whom scientific enquiry and evidence were everything.

One can imagine such a driven and single-minded person being somewhat awkward or oppressive company. But Celsius’ own writings, and the memories of those who knew and worked with him, suggest not. He was, by all accounts, eloquent, polite, sensitive and appreciative of others, calm, easy-going and well liked. Celsius could sing, play the guitar, and was an entertaining conversationalist. A source from the Swedish National Archives3 describes him as ‘a versatile man. He wrote Swedish and Latin verses. Always happy and cheerful, no matter how busy he was, he never seemed to be in a hurry.’

A generation later, another Uppsala astronomer, Bengt Ferner, met with the sister of Joseph Nicolas Delisle, a French colleague with whose family Celsius stayed while he studied at l’Académie des Sciences in Paris. Ferner wrote how: ‘The [by then] old woman talked about him with ecstasy … It is extraordinary how Celsius has been able to just fascinate people into loving him.’4

Monarchs, institutions and peers sought out the unassuming Swede, whose life coincided with those of some of the most renowned names of the era. His contemporaries included Carl Linnaeus, Leonard Euler and Benjamin Franklin: titanic figures of the Enlightenment who, like him, grappled with the biggest questions about the universe and natural world.

Celsius’ career also overlapped with that of his fellow pioneer in the field of thermometry, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736). While every good school student knows that the two men’s respective scales come into perfect alignment at a single point – minus 40 degrees – the scientists themselves never met. And neither of them lived long enough to see their inventions assume lasting worldwide importance and use.

Humans are one of only a handful of animals that have learned to make and use tools. And the most valuable tool we possess in the twenty-first century to respond to the existential emergency of climate change is the manipulation of data – collecting, storing and interpreting information about what is happening around us. Our ingenuity is being put to the test: how can we apply and act on this knowledge to find more sustainable ways to live in harmony with the natural world? It is exactly the kind of problem that captivated Celsius. If he were alive today, he would surely be in the phalanx of Earth sciences, wielding his paradigm-shifting theories and evidence to find the best responses.

Before Celsius pioneered his meticulous methods of logging and analysing records of weather, astronomical and geophysical events, such an approach would have appeared as alien to his peers as alchemy or necromancy seem to us today. We take it for granted now that, to comprehend something, find solutions and make projections, we explore, inspect, research, measure and collate findings. And, in the age of big data, it is self-evident that the more expansive and finer-grained information is, the more insight it can potentially yield. But these are quite recent practices – ones perfected and first applied to climate studies by the man whose name we all recognise, but about whom most know so little: Anders Celsius.

Some changes are either too fast, too massive or too gradual for us to perceive from our personal, terra firma standpoint of the now. Like the beating wings of an insect, a bullet fired from a gun, watching plants grow or the hour hand of a timepiece move around the clockface, we cannot see these things happening, but the proof that they are confronts us every time we glance back. Celsius understood that the tiniest movements recorded by the brass, wood, glass and alcohol of his custom-crafted instruments indicated vast effects taking place over aeons. The sorts of information he collected and curated became the rich and elegant language through which we can describe such things, and accurately predict what will happen next.

Celsius was a progressive and contented internationalist, equally at ease in his native country or among learned colleagues, aristocrats and royalty in Italy, France, Germany or Britain. He was a man far ahead of his time, who understood that natural changes wrought over thousands or millions of years pay no heed to the arbitrary boundaries and orthodoxies through which humans attempt to impose order. He also grasped a new and thrilling concept: that the most successful responses to these phenomena might be realised through the aggregated effects of a multitude of smaller actions.

Unlike many of his contemporaries and peers, Celsius is now little remembered and celebrated beyond the graduations etched onto a thermometer or gauge. The reasons why lie partly in Celsius’ lineage and the rancorous disputes between nations, church and state during the golden age of discovery. The intricate, constantly shifting religious schisms and geo-politics of competing states in eighteenth-century Europe shaped Celsius’ ambitions and opportunities. But his own enigmatic personality and the setting and culture in which he grew up also affect the way he’s remembered now.

Some people are famed for one overriding idea, invention or event. But Celsius’ contributions were more fragmented and broadly spread. His adventures and achievements are not just arresting in their own right, but also for what they reveal about the process of scientific insight and the trials of academic collaboration, criticism and competition. And as to Celsius’ relevance now, we need only observe humanity’s impact upon the Earth and witness its signs of pain. I contend that understanding the mind and methods of Anders Celsius can help us to ask the right questions about our current predicament, and perhaps find some answers.

2

FORGED IN FLAMES

The Origin Story of Celsius the Scientist (1701–02)

There is no education like adversity.

Attrib. Benjamin Disraeli

It was the smell they noticed first. Shortly after midnight on 16 May 1702, a tart whiff of woodsmoke and melting pitch entered the Celsius family house in the centre of Uppsala. Propelled by a stiff Baltic breeze, it seeped invisibly through the eaves and windows, permeating the interior with a pungent sense of danger. Head of the household, 44-year-old Nils, woke with a start, the acrid odour catching at the back of his throat. Around the edges of the painted wooden bedroom shutters, he saw a faint orange glimmer. His wife Gunilla stirred beside him, she too now roused by the bitter aroma that had invaded their home. A quick glance from the window confirmed what they feared: their city was on fire.1

Scooping up their 6-month-old son, Anders, and 6-year-old daughter, Sara Märta, and venturing outside, Nils and Gunilla immediately realised that this was no ordinary fire. The whole sky was lit up in a ferocious, dancing scarlet. Overhead, birds disorientated and driven from their roosts by the inferno, zig-zagged in confusion, their undersides flashing with reflected, iridescent shades of pink and orange.

And now the frightened family registered the sound: a deep roar, growing by the second into an angry howl as the flames consumed everything in their path. It was an elemental force unleashed, its voice growing in belligerence with each structure that fell. At every corner, courtyard and alley, the wooden buildings ignited, intensifying the terrible heat and power of the blaze.

There was no choice but to join the flood of other anxious households streaming out of the city. There were families like them, pushing carts piled high with hastily gathered possessions, as well as stooped figures of older residents, plus merchants and academics with their servants, and an occasional weeping child, distraught at being separated from its parents. Animals too: dogs, rats, cats, goats, hens – even droves of pigs being herded north, the fretful owners flicking sticks at their hairy rumps.

As Nils and Gunilla turned at the end of the street, clutching their children close against the flying ash and embers, they saw an animated line of their fellow citizens silhouetted against the glow. The desperate neighbours had formed a human chain to the riverbank, dropping leather buckets down into the River Fyris on ropes to be hauled up and passed, hand to hand, towards the fire then back to the river. It was frantic and brave, but futile.

Others took to small boats – hurling their belongings on board and attempting to flee the city by heading downstream towards Stockholm. But they ran the gauntlet of burning trees, falling bridges and building timbers crashing into the water around them. Wall by wall and roof by roof Uppsala was being destroyed and, with it, the prospects and prized possessions of most of its 5,000 or so inhabitants. The scorched fragments of all these lives swirled in the wind as the escapees fanned out into the countryside.

When the Celsius family was able to halt at a safe distance and gaze back at the conflagration, it must have looked like the end of days. In just a few hours, so much that was familiar and stable in their world had vanished. Having lost almost everything they owned, how could they start again and build a future in a city that lay in smoking ruins?

Baby Anders, born the previous November, did not and could not know it then, but for him this was a beginning. His parents’ alertness had not only spared his and his sister’s lives, but also marked out his academic path ahead, and they had managed to save most of the precious astronomy and mathematics books belonging to Gunilla’s late father, Anders Spole. These volumes would become the bedrock of the young Celsius’ learning.

Woodcut of the 1702 fire that destroyed the city of Uppsala, by Olof Rudbeck the Elder.

No one is sure exactly what caused the 1702 Great Fire of Uppsala, but it is thought to have started near the main square and town hall, which also housed the city’s board and court. Two neighbours nearby, Professor Upmarck and Academy Rent Master Rommel, had been locked in a long-running dispute over the boundary between their plots. And speculation soon arose that this might have been responsible. Perhaps the simmering enmity between these two prominent men boiled over into arson by one of them, or maybe it was an ill-considered, attention-seeking protest that got out of hand. Either way, the official investigation into the fire in 1704 was unable to determine a specific cause.

But while its origins were unclear, both then and now, its effects were obvious. Apart from sections of the sixteenth-century castle and the cathedral’s stone core,2 most of the city centre was obliterated. But the university’s library and Gustavianum main building3 survived largely intact. Accounts report that, at the height of the fire, a lone male figure was seen standing on its roof, silhouetted against the squat dome that topped the magnificent 200-seat anatomical theatre, one of the finest in Europe. The man’s long hair streamed out behind him as he boomed out instructions to direct the frenzied efforts below. It was Olof Rudbeck – Uppsala’s famed, 72-year-old sage of science, art and humanities.4

Rudbeck had designed and overseen construction of the dome behind him and created the city’s botanical garden – second only to that in Paris – in which the rare and exotic plants had already been reduced to cinders. Despite also losing his home and most of his own substantial book collection in the fire, within a few days of the destruction Rudbeck presented himself to the Uppsala Council with a scroll of plans for the city’s rebirth. The Council adopted many of his ideas, but he never got to see the vision fulfilled. Rudbeck died just four months later, his lungs seared from his valiant rooftop exploits.

In times when guttering tallow candles and lamps were the principal sources of artificial light, urban fires were commonplace. Back to first-century Rome, Sweden’s capital Stockholm in 1625 and, most famously, London in 1666, it was not unusual for whole cities to be devastated. Uppsala had suffered a similar fate before in 1437 – and in parts, would do so twice more in 1743 and 1809. Before the existence of organised municipal services, firefighting resources and techniques were rudimentary at best. In larger places, the authorities sometimes ordered whole streets or districts to be pulled down to create breaks to check the spread of fire. But in Uppsala in 1702, things were both too compact and too quick for this tactic. Once the first few rows of houses were ablaze, and with the wind driving the flames, the fragile wooden city was doomed.

Uppsala Cathedral with the Gustavianum University building in the foreground, c. 1900.

But as its landmarks and treasures disappeared in showers of sparks, good fortune also settled over Uppsala that night. There were apparently no human fatalities at all – each household replicating the lucky escape of the Celsius family. People were able to detect the fire and raise the alarm just in time to dodge death and flee the danger area before they were overcome. But there were many casualties of a different kind: farm, draft and domestic animals left behind, plus wild rodents, reptiles, spiders and insects. Countless individuals from other species perished unseen and unmourned. The fire was a foretaste of far greater global calamity to come.

Anyone visiting the leafy university city today will find few obvious signs of the devastation. Over the decades following the 1702 fire, corresponding roughly to Anders Celsius’ lifespan and presence there, Uppsala was reconstructed on a new and more regular grid street pattern, which drew heavily on Rudbeck’s ideas. The cathedral was restored, albeit without its medieval interior decorations and flying buttresses, while the castle was remodelled onto a smaller footprint, minus a whole wing. But a proud scholarly soul and the determined nature of Uppsala’s inhabitants remained intact. The city and its university rose again.

At the top of the steep escarpment next to the castle a large bell now hangs, suspended within an open framework of hefty timbers bound with solid iron fastenings. Appropriately, and by coincidence, it is named the Gunillaklockan (Gunilla bell), after Sweden’s sixteenth-century queen rather than Celsius’ mother. But it is a fitting (if unintentional) tribute to one of the fire’s innumerable heroines who, with her husband, safeguarded their young son so that his genius could later be realised. The Gunillaklockan is poised to ring out if Uppsala faces another crisis.

Of course there is now another emergency threatening not just Uppsala but the Earth itself. It is a slow-burn catastrophe of unimaginable dimensions, signalled each summer by worsening mega-fires in the forests of every continent. By contrast to the events of 1702, the reasons for these are clearly known and understood. And, unlike the peril that confronted the Celsius family and their neighbours, this time there is nowhere to escape to.

A pre-Great Fire view of Uppsala Castle, Cathedral and the Gustavianum dome, looking east towards the city centre.

Uppsala’s Gunillaklockan tower overlooking the city from the castle.

These are fires humanity has to face. And, if we are wise, we will draw inspiration from the little boy whose future was forged as he escaped the flames in his parents’ arms that May night.

3

A CITY OF LEARNING

Uppsala and Sweden’s Age of Freedom (1720–72)

A man travels the world over in search of what he needs and returns home to find it.

George A. Moore, The Brooke Kerith: A Syrian Story, 1916

Aside from his family’s escape from the Great Fire of Uppsala, a curious combination of other people, places and events influenced Anders Celsius’ birth and early life. It was a three-generation fusion of ancestry, state, royalty, religion, geography, academia, conflict and coincidence that set him on his path to greatness. The Sweden he was born into on 27 November 1701 was a country unbalanced by a struggle for supremacy between Church and Crown and weakened by successive wars with neighbouring Denmark and its allies. Yet the nation was about to emerge into its golden Age of Freedom – an era when bright minds and busy spirits like Celsius could rise up and shine in the European Enlightenment.