14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

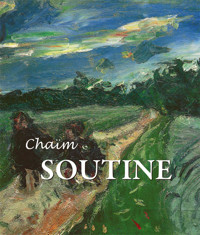

Chaïm Soutine (1893-1943), the unconventional and controversial painter of Belorussian origin, combines influences of classic European painting with Post-Impressionism and Expressionism. As a member of the Artists from Belarus, a group within the Parisian School, he created an oeuvre mainly consisting of landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. His individual style, characterised by displays of humour and despair and by use of luminous colours, makes him a modern master who is still little understood.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 140

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Author:

Klaus H. Carl

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyrights on the works reproduced lie with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Klaus H. Carl

Contents

Introduction

From Smilavichy to Paris

The First Years in Paris

Cagnes-sur-Mer and Céret

Paris – The 1920s

Paris – The First Half of the 1930s

The Nazis in the 1930s

Degenerate Art

World War II and the Persecution of Jews in France

Italy and Spain

Gerda Groth

Marie-Berthe Aurenche

Persecution and Interrogation

Memories of Chaim Soutine

A Selection of Exhibitions

Biography

Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Self-Portrait, c. 1918. Oil on canvas, 54.6 x 45.7 cm.

The Henry and Rose Pearlman Foundation, Inc.,

New York; on long-term loan to the Princeton

University Art Museum.

Introduction

Chaim Soutine was born in 1893 (some biographies cite his year of birth as sometime after 1894) in Smilavichy, a village near the city of Minsk in the current state of Belarus, inhabited at that time by less than a thousand residents. Smilavichy lies in the former Principality of Polotsk, an urban area of the East Slavic Dregowitschi and Kriwitzen that had joined forces with other ethnic groups in the 9th century. This area formed the basis of the Old Russian state of Kievan Rus’, and belonged from the 14th-16th century to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In the 18th century, this region, also referred to as Ruthenia, developed hesitantly and only in the 19th century did it develop a real national consciousness. This was initially difficult, as the entire area was centrally ruled from St Petersburg and was subject to massive attempts of ‘Russification’, which included the maltreatment of the Polish upper class and the banishment of the native dialect.

In the Principality of Polosk lies the city of Minsk, founded as a fortress during the first half of the 14th century. It was first recorded in 1067 and belonged to Lithuania in the first half of the 14th century and again at the end of the 18th century, following the third of the three partitions of Poland (1772, 1793, and 1795), in which Prussia, Russia, and Austria were involved, and during which the entire state of Belarus became part of the Russian Empire. Minsk had received its town charter already in 1499. The city was dominated by the twin-towered Cathedral built in 1611, and it was surrounded by three other Christian churches and monasteries. Reflecting the high proportion of Jews within its population it also had a synagogue and at least forty Jewish houses of worship, and has been the capital of Belarus since 1919.

In the region of Minsk, there lived many East European Jews who practiced their traditional crafts, which passed on from father to son in many families, although the population has greatly decimated since then. The community remained faithful to the traditional life habits and adhered to the strict rabbinical orthodoxy – the essential characteristics of which can be found in shtetls (close-knit Jewish communities mainly found in Galicia and Eastern Europe), the Yiddish language, and Hasidism. In small towns, the Jewish inhabitants were not only tolerated but, despite intermittent persecutions, accepted. The religious and conservative Hasidim seek an internalisation of religious life, lean towards asceticism, and form a close attachment to a Rebbe (master or mentor) as God’s teacher. In the arts, Marc Chagall (1887-1985) is one of the most famous adherents of the Hasidim.

Cité Falguière at Montparnasse, c. 1918.

Oil on canvas, 81x54cm. Private collection, Israel.

From Smilavichy to Paris

Most buildings in Soutine’s home village Smilavichy were partially dilapidated, often next to a ramshackle picket fence enclosing a small plot with shacks that offered paltry accommodation to the large-numbered families. Under these conditions, Chaim Soutine was born sometime in 1893 – the precise date is unknown – as the tenth of eleven children. His father, Zalman Soutine, could only painstakingly feed his thirteen- member family, as he was, even for East Jewish conditions, an unusually poor jobbing tailor. His inability to provide for his family and unstable employment garnered him little respect from the rest of the shtetl community. His mother proved to be an equally difficult parent. Scarred by her harsh life, she spoke very little, not even with her children. When she had to bake the bread supply for the coming week, the children escaped, whenever possible, to avoid the constant threat of slaps.

Of his Orthodox brothers, who were older than Chaim, is only known that they always beat him severely when they found him drawing or sketching or when they found out that he had once again painted the posts or walls of the hut, because his behaviour breached the Orthodox religious commandments. How and from where little Chaim obtained his crayons or his other drawing materials at this time, is difficult to establish. In this very doctrinal congregation, painting and drawing were strictly prohibited; any artistic activity was equated with heresy and blasphemy. Chaim tried to avoid the scuffle by hiding in one of the surrounding forests and only returned home when hunger pains became intolerable.

His parents were not enthusiastic about his artistic inclinations, after all, his father had planned for him a career as a tailor or shoemaker – of course without asking him and despite his already recognisable artistic tendencies – a customary action at the time. Hardly anything is known about Chaim’s educational development. It could not have been too thorough, as later discovered, since at the age of ten his father took him as an apprentice in his workshop for around two years.

Apples, c. 1917. Oil on canvas, 38.4 x 79.7 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

When Chaim was about fifteen years old, he one day asked an acquaintance, a pious Jew from his community, to model for him. The man, perhaps secretly a little vain, needed no second asking. However, he underestimated the reaction of his devout sons or simply forgot to take them into account. They had nothing more urgent to do the day after the modelling session than to beat up Chaim so furiously that he lay helplessly on the ground, and was initially assumed dead. For a whole week he could barely move, and even then he had significant difficulties to get up on his own to edge his way. But his mother surprisingly lent him a hand and sued the brutal thugs. The Court agreed with her and granted Chaim a compensation of twenty-five silver rubbles (about fifty-five Goldmarks in 1915, the modern-day equivalent of €550). The pain of the incident and the help of the compensation, most likely paid under vigorous lament by the rowdies, prompted his decision to leave his shtetl – a place where the artistically gifted were persecuted and where anything outside the realm of knowledge and the shared experience of the inhabitants of the shtetl was rejected. Everything dissenting with, or simply beyond, the controlled Orthodox everyday life was perceived as a threat or as the work of the devil.

Chaim migrated together with his friend from school days, Michel Kikoïne (1892-1968), to Minsk, a city heavily populated by devout Jews, located on the banks of the river Svislach. For both young men, Minsk was the first step into the greater world. Chaim remained in Minsk for nearly a year, but little to nothing is known about this time. Both began taking private drawing classes from the only art teacher in town. He not only took care of his students in this respect, but he also worked to convince Chaim’s parents, who lamented their supposedly lost son, of the appropriateness of his new path.

But the stay here was for Chaim only a (planned?) stop, for he soon moved to the capital Vilnius and applied for a three-year study program at the Academy of Fine Arts. Unfortunately he failed the entrance exam because of a wrong perspective representation of a geometric figure. Here, too, we must refer to an anecdote in the absence of precise information: It is said that Chaim begged his professor, on his knees and in tears, to admit him because he feared having to return unsuccessful and faint-hearted to his village and to assume, unhappily, the profession selected by his father. This professor was so moved that he accepted Chaim into his lectures.

Chaim quickly befriended his fellow classmate Pinchus Krémègne (1890-1981), also from a Jewish family of craftsmen. Both of them studied now for three years. Whether the sombre themes of his work – death, misery, funerals – stem from his depressing childhood or simply portray a stage of development, is open to discussion. Chaim ranked as one of the best students following the examinations and had nothing more pressing to do than to forget his shtetl and Vilna and to leave it as far behind as possible. Along with a generous donation from the Jewish physician Dr Rafelkess, who unfortunately was only a short-term patron, Chaim had successfully saved enough money to purchase a ticket for a trip covering nearly 2,000 km, from Vilnius to Paris, with a short stop in Berlin. And so he emerged in the great, big world.

Still Life with Soup Tureen, 1914-1915.

Oil on canvas, 61x73.7cm.

Ralph F. Colin Collection, New York.

The Artist’s Studio,Cité Falguière, c. 1915-1916.

Oil on canvas, 65.1x50cm. Private collection, Paris.

Still Life withFish,Peppers, and Carrots, c. 1918.

Oil on canvas, 61x46cm. Rafael and

Eva Efrat collection, Tel Aviv.

Self-Portrait with Beard, c. 1917.

Oil on canvas, 81x65.1cm. Private collection.

The First Years in Paris

Soutine was now a twenty-year-old man, eager to learn. Thin as a rail, unable to master the French language and therefore wholly dependent on Yiddish, equipped with a backpack filled with more rolled-up pictures than clothes, he arrived at the train station in Paris. Gare du Nord, the same train station at which many artists from eastern countries had arrived before him and would still arrive after. He had achieved his dream.

At the train station he was picked up by his fellow classmate and friend Krémègne, who had arrived before him in Paris and who lived, like a number of other penniless artists, at La Ruche (The Hive). The building is located in the Passage de Dantzig in the Quartier Montparnasse, a bit hidden behind some trees. As its name, La Ruche, implies, the circular building, with its divided floors and doorless rooms, has the appearance of a honeycomb and had originally been planned and implemented as a pavilion for the Paris World Exposition of 1900 by Gustave Eiffel.

The sculptor Alfred Boucher (1850-1934) – not to be confused with the painter François Boucher (1703-1770) – built in 1902, on the empty property decorated with flower beds, a pavilion called La Chapelle as housing for artists, which from then on served as a studio. Today it is not possible to ascertain who coined the name Villa Medici of Misery for this property that sheltered no less than 200 artists.

For the artists, it was almost vital that Albert Boucher paid little heed to rental payments. The ones without money, and this often applied to many, were sometimes allowed to live there rent free for a while. Here, in this not-very-comfortable accommodation, which was not only populated by artists but also by crawling and scrabbling vermin, Soutine was able to take shelter with his friends Kikoïne and Krémègne, and face the challenges of the near future. It was a poor, miserable future that awaited him there. During this time, Chaim suffered from earache. When he consulted an audiologist, the doctor ascertained that there was no inflammation, as he instead found a bugs’ nest in Chaim’s ear canal.

The impending demolition of La Ruche during the late 1960s was successfully prevented by, among others, the Frenchmen Jean-Paul Sartre (philosopher and playwright, 1905-1980), Jean Renoir (director and actor, 1894-1979), and René Char (poet, 1907-1988) and the American Alexander Calder (sculptor, 1898-1976). The building was renovated a few years later and still stands today, with twenty-three newly furnished studios again available to artists.

Flowers on a Chair, c. 1917.

Oil on canvas, 61.6x49.5cm.

Engel Gallery, Jerusalem.

La Maison blanche (The White House), c. 1918.

Oil on canvas, 65.1x50cm.Collection Jean

Walter et Paul Guillaume, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris.

A great many famous artists lived and worked in La Ruche, including the painters Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Fernand Léger (1881-1955), and Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and the sculptors Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957) and Ossip Zadkine (1890-1967). And here, at La Ruche, Chaim met the Spaniard Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and the Italian Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920), who had lived in Paris since 1906 and had worked earlier in the Cité Falguière where he became acquainted with the most famous painters of those years. Modigliani painted mainly portraits, among others a portrait of Soutine, and nudes of sublime beauty and different kind of eroticism.

If we take these artists and some others, such as the Greek-born Italian Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), the German Max Ernst (1891-1976), or the Spaniard Joan Miró (1893-1983), it brings the main representatives of the École de Paris of those years together. Needless to say that this school was not a school in the standard sense, as its first members were already influential at the end of the 19th century, in art movements like Art Nouveau and Fauvism. The school was rather a loose connection of like-minded artists who were all looking for something new. The above list, due to the numerous excellent artists involved, is by far incomplete. Unnecessary to call special attention to a third fact: the works of these artists – exclusively male artists – hang today in the most prestigious museums and belong to many wealthy collectors. They are among the most sought-after works of all time and realise prices that the artists would never have dreamed of during their lifetimes.

Modigliani introduced Soutine – the two entertained a lifelong friendship – in 1915 to Chaim Jakoff Lipschitz, a Lithuanian-born French-American sculptor known as Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973). Modigliani was also the one who introduced the now twenty-three-year-old Soutine to the art dealer Georges Cheron, who had recently opened the small Galerie des Indépendents near the Champs Élysées in the 8th arrondissement, where he exhibited one of Soutine’s works: The Portrait of the Painter Richardx(1915). This was his first work to be exhibited in a gallery. It is precisely Lipchitz, who was not sure if he liked Soutine or not, who described him as “[...] one of the rare examples of a painter of our time, who can let the light shine with its colour pigments. This is something that can neither be acquired nor learned. It is a gift of God.”

Poplars, c. 1919. Oil on canvas,

65.1x81cm. Private collection.

La Table (The Table), c. 1919.

Oil on canvas, 81x100cm.

Collection Jean Walter et Paul Guillaume,

Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris.

Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, 1917.

Oil on canvas, 91.7x59.7cm.Chester Dale Collection,

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Modigliani’s friendship with Soutine is also evident in the two portraits of Chaim Soutine (1915, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart and 1917). On these two portraits, Soutine’s dense black mop of hair is perceptible, he groomed intensively. It was said that out of sheer fear of premature hair loss, he would wipe fresh eggs in his hair and, without washing out the grease, would put on a hat and go for a walk. Incidentally, Soutine had an almost unshakable fidelity to hats, which went so far that he later, when an established artist, bought a countless number of blue hats and at times he even believed to be able to walk incognito through Paris.