Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

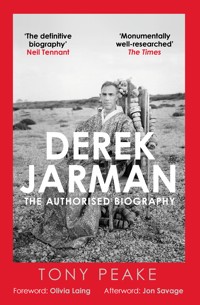

Tony Peake enjoyed unprecedented access to the visionary artist's archives in order to bring the extraordinary life of Derek Jarman to the page. This authorised and unique biography covers Jarman's story from the bleakness of post-war Britain and his RAF childhood, to student life at The Slade and his work as a designer, painter and filmmaker. It tells how energetic home filmmaking with dazzling friends led to distinctive feature films including Sebastiane, The Tempest, and Caravaggio. There were collaborations with the likes of Sir John Gielgud and Tilda Swinton and Jarman was also at the forefront of popular culture, producing distinctive music videos for Pet Shop Boys and The Smiths. Alongside his art and a significant body of writing, Jarman created a singular garden in the shingle surrounding Prospect Cottage at Dungeness in Kent, which has become a site of memorial, celebration and pilgrimage. He became known as an impassioned and provocative spokesperson not only for gay men, but for anyone oppressed by bigotry. Derek Jarman died of AIDS-related causes in February 1994 and Peake describes his inimitable courage and grace in the face of painful death, and the legacies Jarman left behind. With new contributions from Olivia Laing and Jon Savage.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1294

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iii

DEREK JARMAN

THE AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY

TONY PEAKE

Contents

Foreword

Tony Peake’s biography of Derek Jarman was first published in 1999, half a decade after its subject died of AIDS-related complications, on 19th February 1994. During his last years, Jarman had been hyper-visible. In that homophobic and frightening period, he had taken the rare decision to make his diagnosis public. His regular appearances in the media, combined with the publication of his memoirs and the prominence of his garden at Dungeness, introduced him to a far larger audience than knew him from his films or paintings. At his death, Jarman was that rare thing; a controversialist whose courage and charm made him internationally beloved.

The fact that this biography has been out of print for over a decade suggests that such easy acceptance was not the whole truth. Jarman was a genuinely radical figure, a deeply complex man whose presence in British culture remains even now, to some extent, unassimilable. His queerness, and his uncontainable fury at the exclusion this caused him, didn’t make him bitter, but it did make him passionately antagonistic to many existing power structures and public figures. Objects of his fury included Channel 4, for hesitating over the funding of Caravaggio, and Sir Ian McKellen, viiicastigated for accepting a knighthood during the era of Section 28. Then there was the work itself, kicking off in Sebastiane with a film that not only featured well-oiled male nudity, but dialogue entirely in Latin. Assimilation into conventional society was never the intention.

Jarman was blessed in his collaborators, gifted at attracting like-minded talent, and this holds true for his biographer, too. Tony Peake was originally his literary agent. They met in 1985, when Jarman was working on Caravaggio. Peake initiated the idea of a biography in the final years of Jarman’s life, but didn’t begin working on it until after his death. The portrait he assembles here is scrupulous, fascinating, wry, attentive to the peculiar poetry of Jarman’s vision while gently puncturing some of its subject’s more farfetched tales. It lays open the deep complexities and divisions of his nature without trying to resolve or tidy them away. Poppers and Pevsner; the medieval paradise and the wild boys picked up at Heaven: Jarman’s art was founded on just such productive tensions.

The schism began in childhood. Jarman’s father Lance was an RAF officer and after the war the family relocated to Italy, where he was billeted. This ‘fabulous floral idyll’ formed the cornerstone of Jarman’s adult imagination, introducing him to such lifelong sources of sustenance as gardens, cinema and the art of the Renaissance. The return to England was brutal. At prep school, he was inculcated into a code of deprivation and austerity that he never quite unpicked, despite his determined efforts to refuse its homophobia and repression. The lack of self-pity around his illness was a direct legacy of this early training in the stiff upper lip.

The giddy Sixties were when he began to shed his shame about his sexuality. He discovered cruising and found a place among London’s beau monde. This era of party-going, centring around his beautiful room in a Bankside warehouse, gave way to much harder-edged and more explicitly sexual 1970s. Love came late, but when it did it was both permanent and unconventional in form.

What shocked me, reading this book as a romantic young person in 1999, was the revelation that Jarman’s love affair with Keith Collins, the ‘HB’ of the diaries, did not have a sexual component. As Peake puts it: ‘As usual, Jarman had fallen for someone who did ixnot find him in the least sexually attractive … In any other circumstances, this might have created considerable tension; as it was … with the pressure lifted, he and Collins found they could enjoy each other’s company in almost every other way. A new passionate friendship was born; the most passionate and enduring of them all.’

Collins was Jarman’s archetypal beautiful lad, a Geordie as intelligent as he was strikingly attractive, as wild as he was dedicated and loyal. They met at a screening when he was twenty-three and Jarman forty-four. Both had other sexual lives, but the commitment between them endured to the end. Peake is very delicate in his probing here, allowing the possibility that the arrangement was both radically freeing, defying the stifling heterosexual imperative to locate love, sex, romance and domesticity in a single person, and also potentially a source of disappointment or longing.

What is evident is that the love between them never diminished, despite the ever more gruelling experiences of Jarman’s illness. The last words written in his diary, when he had lost his sight and was very close to death, were: ‘HB true love.’ However unlikely or unconventional the relationship had seemed, it lasted. As Peake movingly puts it, it was ‘a contract of care on which the younger man would never renege.’ Keith Collins died tragically in 2018, of a brain tumour. He was fifty-four. He never did renege on his commitment, and the maintenance of Jarman’s posthumous reputation owes an enormous amount to his ongoing love and dedication.

One of the reasons Jarman is so wildly popular with young people, and especially young artists now, is that he models, more than anyone of his generation, a dogged following of one’s own vision, no matter how far it travels from the commercial sphere. He was never motivated by money, or status, or reviews, or any other worldly reward. What Jarman practised was art as a way of living; or life as a process of making – and especially of making in company, amid a lively circle of collaborators.

He was often charged in his lifetime with being amateurish, but what emerges most powerfully from these pages is how dedicated, almost ruthless he was, in pursuit of his own strange and idiosyncratic xideas. How he got the work made, on a shoestring and against all odds. How he struck gold from the dark, like the alchemist he was so often compared to, and how brightly it glows now, when he is no longer present to animate or explain it. What a clutch of visions he left us, and what an uncompromising, fiercely inhabited life he led.

Olivia Laing, Suffolk, 2024

Prologue

As I write this, some thirty years have elapsed since Derek Jarman died, while over twenty-five will separate the moment when my biography first appeared and this re-issue. Such a distance allows of course for new perspectives; the chance to comment afresh on what I originally wrote. But then I ask myself: where would I stop? And anyway, to my way of thinking, new perspectives are best delineated by new eyes.

I’ve therefore decided to leave what’s written (apart from some minor changes to the end matter) exactly as is. And so we begin, now as then, with:

The picture on the front page of the Independent was of an unequivocally bespectacled man photographed against a hazy bank of flowers in Monet’s garden at Giverny. Wearing a cap, scarf and rumpled tweed jacket, he had a book clasped tightly in his left hand, a walking stick in the other, and was confronting the camera with a steady gaze subtly suggestive of a smile.

The caption read: ‘Gay champion dies on eve of new age.’ It might have added a number of other epithets: painter, designer, 2film-maker, writer and gardener. The ‘new age’ (prematurely announced) was a reference to the parliamentary vote being taken that evening, 21st February 1994, to give homosexuals parity with heterosexuals by lowering the age of consent for homosexual sex to sixteen.

Later that night, as Parliament settled on a compromise age of eighteen, disappointed protesters on the pavement outside fell momentarily silent in the dead man’s honour. The doorstep of Phoenix House, the block of flats in Charing Cross Road where Derek Jarman had latterly lived when in London, was adorned with candles, as was the exterior of the nearby Waterstones bookshop, where copies of Chroma, Jarman’s most recent book, graced the window. Shipley’s, a bookshop that took particular care to stock everything he had ever written, created a small shrine to his memory. So did Maison Bertaux, the coffee shop in Greek Street where he had been a devoted regular, and Presto in Old Compton Street, where he often ate. Soho was saluting one of its denizens – though, as coverage in the national papers indicated, Jarman’s fame stretched far beyond the nexus of streets where he had lived. By the time his other home, a simple cottage at the tip of Romney Marsh, came to witness his funeral, news of his death had circled the world.

It was 2nd March 1994, the most perfect of early spring days. The sky was clear, the viridescent fields dotted with tentative lambs and occasionally splashed with the red of budding willows. Those who arrived in good time went first to Dungeness where, on the windswept shingle between the looming ugliness of the nearby power station, the fishing huts and the slate-grey sea, Jarman had famously created a sculptural garden of great unusualness and beauty. Passing through the cottage’s dark wooden rooms, more redolent of a Russian dacha than of anything English, one arrived at the newly constructed ‘west wing’, a plain room overlooking the rear garden. The curtains were drawn, candles guttered, a small grapefruit tree filled the air with its scent. One of Jarman’s most treasured possessions – a plaster cast of the head of Mausolus, the ancient king whose tomb gave the world the word ‘mausoleum’ – locked unseeing eyes with the room’s central occupant. The plain oak coffin was open. Jarman was dressed in a robe of glittering gold. The cap on his head proclaimed him a ‘controversialist’. People came and stood in silence over the coffin. 3They hugged and spoke quietly with Keith Collins, Jarman’s companion, and with Howard Sooley, the photographer friend who had faithfully recorded the last years of Jarman’s life. Earlier that day, Collins had placed a number of carefully chosen effects in the coffin. The designer Christopher Hobbs, one of Jarman’s oldest friends, now added a small brass wreath similar to the one he had last fashioned as a prop for Jarman’s filmic account of the painter Caravaggio. The actress Jill Balcon, who had appeared in two of Jarman’s later films, Edward II and Wittgenstein, supplied a second wreath, of laurel. As the mourners left this temporary mausoleum, they encountered another line of people in the passage outside, queuing to use the bathroom, whose walls of blue stood testament to Jarman’s final film, an imageless journey into a blue void.

In the garden people wondered whether the silent, sightless, shrunken form in the coffin could possibly be Jarman. The face was familiar and, no doubt, the feet – absurdly huge and pale in comparison with the tenuous, umber features above them. Yet the talkative, excitable Jarman had never been that small, that Mandarin-like, that still. The only thing that felt right was that he should be the centre of so much attention.

Spilling from the garden into the road, groups of black-clad people came and went, talking in hushed tones. Many had ribbons on their lapels, some red to acknowledge support for AIDS-related charities, the majority blue, the colour of that final film: acknowledgement less of a disease than of a particular victim. Equally unusual were the flapping habits of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, men who dressed as nuns in order to expiate homosexual guilt and promulgate universal joy. Three years previously, these same sisters had come to Prospect Cottage to canonise Jarman. Then, the occasion had been a party and some of the sisters had taken their new saint for a paddle in the sea. Today there was no paddling. It had not been easy for Jarman, an avowed atheist and relative newcomer to the area, to obtain permission to be buried locally. When permission was obtained, it was on condition that proprieties were observed. The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence were on notice to behave with uncharacteristic decorum.

To those more familiar with the rebellious side of Jarman’s persona, 4the controversialist in him as opposed to the traditionalist, the service that followed was as puzzling as it was inappropriate. Conducted by Canon Peter Ford in the Church of St Nicholas in nearby New Romney, it consisted of prayers, readings and two hymns, both chosen by Jarman: George Herbert’s ‘Teach Me, My God and King’ and ‘Abide With Me’. Also at Jarman’s request there were four addresses. Nicholas Ward-Jackson, the producer of Caravaggio, remembered the almost feverish excitement with which Jarman had made the announcement that he was HIV positive. Norman Rosenthal of the Royal Academy recalled the dead man’s gift for friendship. Sarah Graham, herself a political activist, detailed his contribution to the cause of gay politics. The journalist and critic Nicholas de Jongh referred memorably to the ‘significant mischief’ inherent in Jarman’s attitude to life.

Since it was Lent, there were no flowers in the church, but Jarman’s sister Gaye had supplied a single bouquet of mimosa, a flower of particular importance to her brother. This lay on the now sealed coffin and, as the coffin was carried from the church after the closing hymn, its scent hung in the still air.

The congregation dispersed, some covertly complaining that they had not been invited to join the immediate family and select coterie of friends who made the short journey to Old Romney and the small churchyard of St Clement, where final prayers were said and the coffin was lowered into the ground in the shade of the ancient and venerable yew tree of which Jarman had been so fond.

Had he died seven years previously, on completion of Caravaggio, although almost as many people might have attended his funeral, and from as many walks of life, he would never have made the front page of a national newspaper. Then, if he was known at all, it was principally to dedicated filmgoers and cognoscenti of the artistic avant garde. In the interim, his diagnosis as HIV positive and his decision to be open about his disease, his ineluctable Englishness and the extraordinary grace and courage with which he faced death, all led to his achieving iconic status in the eyes not only of his most obvious constituency, gay men, but of almost anyone with a care for the human spirit.

The commemorations continued, one within days of the funeral. 5Glitterbug, a compilation of Jarman’s super-8 footage put together for BBC Two’s Arena, was hastily scheduled for broadcast on 5th March. Channel 4 responded with A Night with Derek, a repeat of a profile entitled You Know What I Mean, plus four of Jarman’s features. There were three exhibitions, the first in Portland at the Chesil Gallery and Portland Lighthouse, the second at Manchester’s Whitworth Gallery, the third at the Drew Gallery in Canterbury. A dramatisation of Jarman’s journal Modern Nature was performed at the Edinburgh Festival. Richard Salmon, Jarman’s art dealer, produced a limited edition of the text of Blue. There was a season of his films at the National Film Theatre. Making magnificent use of Howard Sooley’s photographs, Thames and Hudson published derek jarman’s garden. The steady trickle of visitors to Dungeness become a flow. Keith Collins began to joke darkly about establishing a company called Prospect Products.

As in life, eulogy was tempered by controversy. Even before the funeral, Christopher Tookey, film critic of the Daily Mail, was writing a rebuttal of Jarman under the heading: ‘how can they turn this man into a saint?’1 A piece by Ed Porter in the Modern Review asked: ‘Had Derek Jarman not been gay, would his home videos have been shown on Channel 4?’2 Arguing that if he had ‘not taken the HIV test or drugs like AZT, he could be alive today’, a letter in the Pink Paper3 wondered whether his death was not ‘self-willed’. Behind the scenes, there were fierce arguments between Collins and the local parish council over the exact form of Jarman’s gravestone, erected in June 1997.

In May 1996, a comprehensive retrospective of Jarman’s work was mounted at the Barbican. Thames and Hudson published Derek Jarman: A Portrait, a collection of essays complementing the exhibition. The critic Brian Sewell gave the work on display a decided drubbing and concluded: ‘Without the alchemist, there is no alchemy.’4

He may well be right. Only time will tell. It is certainly true that Jarman’s undoubted gift for turning dross to gold lay as vividly in his persona as it did in his work. Genius is a much overused word, but if Jarman had genius, it resided as much in the sheer incandescence with which he existed as it did in the fruits of that existence.

6‘Do you know what I mean?’ had always been his catchphrase, endlessly punctuating the excited flow of his talk. The hope of this book is to give some sense of what he did mean, to capture the complicated sweetness of honey produced from the lion’s mouth.

In an interview containing an attack on, among other things, the Bloomsbury Group, Jarman said of biography:

I have a horror of Bloomsbury in an odd sort of way. I can’t bear it. But then it was all literary based, wasn’t it? My environment isn’t. That’s why it’s perpetuated through our culture through the TLS and everything because it’s all novels. I don’t know any novelists, thank God. Otherwise we would be stuck like that; there would be endless biographies. It’s a whole industry, isn’t it? It’s extraordinary. It’s so uninteresting. I mean it’s so genuinely dull.5

The subject of this biography could not have been dull if he tried.

1

Family Mythology

In Dancing Ledge, the first of his published journals, Derek Jarman titles his brief account of his family background ‘A Short Family Mythology’. The Viceroy’s Ball, Great-Aunt Doris and her rubber roses, grandmother Moselle – or Mimosa, as he called her – a daffodil bell hanging from a lychgate. The clips are short but telling, scenes snipped from an expert’s home movie; and there is an actual home movie, complete with inter-titles, to complement the journal: severely bonneted toddlers at play in the twenties, Moselle stepping eagerly from a biplane at Le Bourget, a family lunch.

The family thus featured are the Puttocks, Jarman’s forebears on his mother’s side. There is no equivalent memorial to the Jarmans,1 only written records of how the family, based in Devon, moved about the county as work or marriage dictated until, in 1814, Elias, a tanner, married Mary Elworthy, whose family owned the manorial rights to the village of Uplowman, a scattering of houses and tiny farms on the steep hills to the north-east of Tiverton. Here the couple settled, taking over the management of a modest farm at Middle Coombe.

With only two exceptions, the eight children of Elias’s and Mary’s 8third son, John, forsook Devon for New Zealand. The last to leave was the eldest, also John, who set sail in 1888 and eventually acquired a smallholding in Riccarton, now a suburb of Christchurch.

It was in this most English of colonial cities that the second of John’s four sons, Hedley Elworthy, met and married Mary Elizabeth Chattaway Clarke, a carpenter’s daughter. Hedley worked for the Tramway Board, first as a clerk, finally as general manager. In his spare time he played the violin in the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra, sang in the church choir, acted as churchwarden. He was a Rotarian and Grand Master of the Riccarton Masonic Lodge, deviating from this civic-mindedness only to indulge his passion for dancing the waltz.

The second of Hedley and Lizzie’s five children was a son, Lancelot Elworthy, born on 17th August 1907. Obliged from a relatively early age to make his own way in the world, Lance left school at fifteen to become an engineering apprentice with the Christchurch Tramway Board. Meanwhile he attempted to improve his prospects by embarking on a part-time course in mechanical and electrical engineering. In October 1928, underwritten by money scraped together by his family, he sailed for England aboard the SS Ionic to pursue his engineering career in the Royal Air Force.

Regular letters home provide a vivid picture of Lance’s first ten years away from the certainties of New Zealand. Of his first encounter with an official at the Air Ministry, he wrote: ‘They do not like New Zealanders being trained unless they are going to live permanently in England.’2 Although he was almost immediately granted a temporary commission as a pilot officer in the RAF, at his second training school, where he acquitted himself admirably, the comment was: ‘A very conscientious and hard worker Colonial who has brains and power of application.’

The praise is fulsome, the subtext unmistakable – certainly to anyone who has suffered the insularity of the English. It was an insularity Lance felt keenly. To counter it, he set about reinventing himself. He changed his name to Mike3 and, by October 1933, just five years after his arrival, was writing to his mother: ‘I only hope that when I return home my speech will appear normal to you, as 9[a friend] remarked that I had no colonial accent at all.’ He had entered that pernicious no-man’s-land occupied by many such colonials, where, in self-defence, he began to nurture an idealised and fiercely conservative vision of the country to which he pretended.

For all her ‘stiff-necked conventions’, England nevertheless offered Lance unrivalled opportunities. On receiving a permanent commission in the RAF, he had been posted to Palestine, flown over large swathes of East Africa and danced at every opportunity: ‘I have done so much dancing lately I am becoming a super snake at it, rivalled only by the gigolo we saw in the cabaret at Mombasa.’ His aunt Emily (one of the two children of her generation not to emigrate to New Zealand) was still alive, her Exeter home providing a family base of sorts. He had a small but close circle of friends and the time and funds to indulge his various passions: cars, sailing, swimming, sunbathing and photography. He was having fun, more fun than many: ‘Last Wednesday I had a day out in London and saw some of the unemployed riots in Trafalgar Square. Things looked very ugly for a time until a charge from the mounted police damped the hunger strikers’ enthusiasm a bit … I had a dancing lesson in the afternoon and in the evening went to the Palladium to hear Paul Robeson.’4

By mid-1938, now elevated to the rank of squadron leader, Lance was a less enthusiastic dancer than in his twenties. All the same, come the final mess ball of the season, he invited several guests, including ‘two girls from Northwood’. On 16th November he wrote: ‘I motored over to Northwood, North London and stayed the evening there.’ A month later his letter enclosed ‘several snaps, some … with the daughter of the house at Northwood where I stay sometimes at weekends’. Northwood was where the Puttocks lived and the ‘daughter of the house’ is almost certainly the twenty-year-old Elizabeth Evelyn, or ‘Betts’, as she was known.

It is a testament to Lance’s strength of character – and to the enduring love that soon developed between him and Betts – that he was able to spend as much time as he did at Northwood. Betts’ parents, Moselle and Harry Litten Puttock, were neither rich nor particularly well connected, but they had in their time enjoyed the trappings of a quite splendid lifestyle. Snobbish Moselle wanted more 10for her daughter than marriage to the son of a New Zealand clerk eleven years Betts’ senior, however fit and handsome he might be.

It is not known when or where Moselle, also called May, or ‘Girlie’, and her flamboyant sister Doris, also called Sophia, were born; probably between 1885 and 1890 in either South Africa or India. Their father, Isaac Fredric Reuben, was, as his name suggests, Jewish. Tall, dashing and moustachioed, with a fondness for oysters and Guinness, he was an army officer, though in which regiment, even which army, is not recorded. His wife Flora died when the two girls were very young, leaving them to the principal care of a series of governesses who brought them up as Christians.

Although Doris was the more extreme of the two, Moselle was not without dash. Intrepid, vivacious and exceptionally extravagant, she was dark-eyed and dark-haired, glamorous in a decidedly un-English way. She dressed exquisitely, usually in pastel shades, and always made sure that the silk tips of her cigarettes matched the colour of her clothes. By contrast, Harry Litten Puttock, despite a shock of red hair, was as mild and inoffensive as his background. The son of a commercial clerk, he was born in uninspiring Stoke Newington in 1883. As a young man, he had joined the firm of Harrisons & Crosfield, the tea and rubber merchant, thereby quitting Stoke Newington for more exotic Calcutta, where he made a steady but unspectacular climb from tea-taster to manager.

The couple had three children: Edward Colin Litten (Teddy), Elizabeth Evelyn (Betts), and Moyra Litten. Teddy was born in 1915 in London; Betts, on 8th August 1918, and Moyra, seven years later, in Calcutta. Until the age of seven, London and Calcutta would signify the contrasting poles of the children’s environment: innumerable servants, the endless tennis and garden parties, of what Jarman would later term ‘subcontinental suburbia’5 alternating, in due course, with boarding-school life back in England.

For families such as the Puttocks, the interwar years were an extraordinary time. Their existence bore scant relation either to their own particular histories or to a changing world. How often in the past – or the future – would a girl like Betts, at the age of sixteen, have the opportunity to ‘come out’, as she did in Calcutta during the Christmas season of 1934, and attend not only a plethora of garden 11parties, but even the Viceroy’s Ball – where, fittingly, all the decorations, even the tablecloths and sweet wrappings, were imperial purple?

To turn the pages of most family photograph albums is to risk experiencing a sense of loss. In the case of the Puttocks, whose yellowing photos are enhanced by their home movies, that sense is particularly acute. Toddlers at play on the beach at Bexhill, Moselle stepping eagerly from that biplane at Le Bourget, the uniformed girls returning to school at the end of the summer holidays, the caption that joshingly informs us the girl squinting shyly at the camera is the ‘always smiling Betty’ – the flickering images record a way of life that has vanished forever; a lost Eden, but an Eden, too, that is haunted by the spectre of what lay behind it. Little wonder that when Jarman came to pick up a camera of his own, his work should be steeped in a sense of paradise lost, a paradise which, even as he yearned for it, he mistrusted, because he knew that somewhere, somehow, it was poisoned.

In 1935 Harry suffered a minor stroke. It forced him to take early retirement. A friend from Calcutta had settled in Northwood, still a village on the outskirts of London. Here the Puttocks moved, staying first at the Château de Madrid, a residential hotel that would later become the headquarters of Coastal Command, then at Manor Cottage, 9 Watford Road, a pretty, if unremarkable, Edwardian dwelling with an ample garden. Harry’s early retirement meant a disastrous withering of income, his poor health a flood of medical bills. There were still family holidays in Cornwall and Bexhill, and a whiff of imperial excitement seeing Teddy off to India, where he was due to join a tea firm, but taking the waters at Contrexville and gracing the Viceroy’s balls were now a thing of the past.

Betts briefly attended the Harrow Art School with her friend Verity Shierwater. She studied dress design, then found work as an assistant to Norman Hartnell. The job was hardly exalted, paying barely enough to cover her fare into London, but it did have the benefit of glamour. There were clothes to prepare for royal tours, film stars to flatter, fashion shows to announce. In future, Betts would always be able to make her own, exceptionally stylish outfits.6

12Less glamorous – though it did involve excitement of a sort – was the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), which Betts had joined in 1936, again with her friend Verity, plus two friends of Moselle’s, the Aunties Orr – Phil and Vi – two ‘small and birdlike’7 spinster sisters who lived in an old Northwood house called Langlands. The growth of the VAD was one of many pointers towards the deteriorating international situation. Another was the number of young men in the forces for whom, when they were at play, consorts were needed. Harry Puttock was an old-fashioned man, and Betts was not allowed out unless he and Moselle had vetted her beau; but because the evening had been proposed by friends, who would be in attendance, in late 1938 she was given permission to accompany a man she had never met – Squadron Leader Jarman – to a dance at a nearby airfield.

Four months later, in March 1939, Harry died of a stroke. In the summer, Moselle, Betts and Moyra moved into 10 Chester Place, a modest, two-bedroomed flat in a newly built, three-storey block in Green Lane, just around the corner from the station and above a parade of shops. It was a further reduction in circumstances, and one that it fell to the efficient Betts to oversee. About its only positive aspect was that Moselle was now less able to turn up her nose at her daughter’s suitor.

Exactly a year after Harry’s death, on 31th March 1940, Lance and Betts were married at Holy Trinity Church, Northwood. The vicar’s wife made a wedding bell of daffodils which hung on the lychgate. As the dashing squadron leader paused underneath it to gaze adoringly at the smiling bride on his arm, the moment was caught by the camera. The photograph appeared in no fewer than seven papers.

Within a week, the reality of war had reasserted itself. Lance was in the air again, reconnoitring the Danish coast. Three months later he was transferred as chief flying instructor to a training unit in the remote Scottish fishing village of Lossiemouth. In July 1940 he was invested with the Distinguished Flying Cross, and that December he was promoted to the rank of wing commander. A year later he was transferred to Lichfield, this time as commanding officer. Meanwhile, Betts had become pregnant. In January 1942, after a tense few months in which it was feared she might miscarry, she returned 13home to give birth. A friend had been put on notice to save enough petrol to drive her to the hospital, which he did, through heavy snow, on the night of the 30th. The next morning Moselle and Moyra sent a card to the Royal Victoria Nursing Home, Pinner Hill. It read: ‘Congratulations on a happy landing.’ Not long afterwards, Betts and Lance were sending out a card of their own: a drawing of baby Derek assailing the blue in a single-engined plane.

He was Derek from the start, though when he was christened two months later, on 28th March, at Holy Trinity Church, Northwood, it was as Michael Derek Elworthy.

In June 1942, in the same month as he was mentioned in dispatches, Lance was transferred from Lichfield to Eggington as senior air staff officer. In April 1943 he went to Kirmington to command No. 166 Squadron. In October came a further move, to RAF Wyton, also as commanding officer. Although Betts and baby Derek joined him on each of these postings, they spent as much time at 10 Chester Place, not least because Betts was again pregnant and again fearful of miscarriage. In the event, the pregnancy passed without incident and, on 18 September 1943, she gave birth to Elisabeth Gaye Elworthy, who, like her brother, would always be known by her second name.

Meanwhile, Lance’s war had taken a venturesome turn. Having volunteered as a Pathfinder, a position which involved flying ahead of the bomber squadrons and dropping flares to illuminate the targets, in June 1944 he was posted to Italy as a senior air staff officer with the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces.

This meant that for the last year of the war, Betts and the children were forced to remain in England on their own. As soon as hostilities ended, Betts returned to Northwood, where her mother was able to supply her with accommodation: after Harry’s death Moselle had put Manor Cottage, the old family home, on the market, but before it found a buyer, war had been declared and the house had been requisitioned by the army. It was now returned to Moselle, who divided it into two flats, one of which she offered Betts.

During Lance’s final English posting, at RAF Wyton, Betts had acquired help in the form of a young girl from nearby Huntingdon called Joany. Betts brought Joany with her to Northwood to help 14with house and children. When, in early 1946, she was finally able to join Lance in Italy, it was again with Joany in tow. They travelled by train in the first wave of service families to venture on to the continent. The journey was not easy, but for four-year-old Derek it was a huge adventure. To be quitting their ‘bleak wartime married quarters with their coke stoves and mildew’8 felt like a liberation. The journey’s end was magical: family reunion, sunlight and warmth. Filmically speaking, they were switching from black and white into colour.

2

Beautiful Flowers and How to Grow Them

‘Roses. There is a charm about a beautiful Rose garden which appeals irresistibly to every lover of flowers. It is not necessary to win a prize at a Rose show to enjoy Roses when they are used in free, informal, natural ways. There is a wide gulf between exhibiting and gardening.’1 Published in 1926, Beautiful Flowers and How to Grow Them is a substantial work. A mere thirty-two colour plates illustrate 400 pages of dense text. Even so, the Jarmans deemed it an appropriate gift for their four-year-old son, to whom it was given on 25th April 1946, shortly after the family’s reunion in Italy.

At Manor Cottage, little Derek, or ‘Dekky’ as his doting grandmother called him, had wandered into the garden which, owing to the neglect of war, had become hopelessly overgrown. He picked nearly every flower in sight, studying each one with intense pleasure as he did so. ‘These spring flowers,’ he would later write, ‘are my first memory, startling discoveries; they shimmered briefly before dying, dividing the enchantment into days and months, like the gong that summoned us to lunch, breaking up my solitude … In that precious time I would stand and watch the garden grow, something imperceptible to my friends.’2

16After Northwood, Italy was a fabulous floral crescendo. The gardens of the villa where the family spent their first summer were, in Jarman’s words, ‘a cornucopia of cascading blossom, abandoned avenues of mighty camellias, old roses trailing into the lake, huge golden pumpkins, stone gods overturned and covered with scurrying green lizards, dark cypresses, and woods full of hazel and sweet chestnut’.3 Very much a product of England, and a war-torn England at that – his first reaction on seeing the Coliseum was to comment on how badly it had been bombed – little Dekky was ravished, in imagination if not in reality, by the vividness of the colours, textures, sounds and scents which Italy presented him.

The dawn would bring Cecilia the housekeeper bustling into my bedroom – with a long feather duster to shoo out the swallows that flitted through the windows to build their nests in the corners of the room … After breakfast Davide, her handsome eighteen-year-old nephew, would place me on the handlebars of his bike, and we’d be off down country lanes – or out on the lake in an old rowing boat, where I would watch him strip in the heat as he rowed round the headland to a secret cove, laughing all the way. He was my first love.4

The image is splendidly romantic, splendidly romanticised, and was of such importance to its somewhat precocious author that, love-struck, he would return to it a number of times in his writings and films.

Lance was based in Rome, a city which, for all its splendours, is simply too hot in high summer. With Lance flying up for weekends, Betts, Joany, Derek and Gaye found themselves billeted with a number of other air force families in the villa with the magnificent gardens, the swallows, Cecilia and Davide. Situated on the shore of Lake Maggiore, the Villa Zuassa had been requisitioned by the Allied Commission from a Fascist whose wife, ‘a sinister figure with a string of alsatians’,5 was still in residence. Her baleful, witch-like presence in the other half of the villa could cast a shadow across this Italian Eden as dark and alarming as the stormclouds that occasionally gathered across the lake.17

There were other shadows. In most respects little Dekky was a model child, impeccably turned out, well-mannered and cheerful. In matters prandial, however, he was proving something of a rebel. Usually it fell to Joany to feed the recalcitrant child. ‘Eat this for little Joany,’ she would croon – until Betts’ sister, Moyra, who happened to be staying, could stand it no longer. ‘For God’s sake,’ she snapped, ‘eat that for bloody little Joany.’ Thus did ‘Bloody Little Joany’ acquire a nickname and Jarman a reputation for being difficult at table. It was a reputation that would soon bring him into fierce conflict with his father, who up to now had seen very little of his son.

That winter, after a brief stint in Venice, the family took up residence in Rome, a city then remarkable for its emptiness: ‘There were very few cars, everyone travelled on bicycles. Limbless soldiers and maimed children begged in the streets and lived in the ruins on the Via Appia, a quiet little lane that wound into the countryside. At every turning there were priests like flocks of crows, scurrying busily about their work.’6 They were billeted in a cavernous nineteenth-century flat in the Via Paisiello, not far from the Borghese Gardens – another of Jarman’s Edens.

The flat, requisitioned from Admiral Count Costanzo Ciano, the father of Mussolini’s son-in-law, was cruelly cold; unless packing cases could be found to burn in its many grates, the only warm room was the kitchen. For Dekky, however, its art-deco grandeur more than compensated for its chill. He was overawed by the echoing marble, the parquet floors, the tiger-skin rug, the copy of Titian’s Sacred and Profane Love, the suits of armour. He adored the attic, where there was a further treasure-trove of astounding objects: a small glass dome which, when shaken, produced a snowstorm; a violin, a doll, a collection of ceramic donkeys, old ballgowns and ‘two circular ostrich-feather fans with handles, sown with hummingbirds, a tinsel Christmas tree, and letters to the Admiral from Mussolini scattered across the floor’.7

In an adult notebook, Jarman once compiled the following list:

curriculum vitae Art History self portrait romance

1) the swallow who flew into room at Largo mas18

2) the red glass ball with the snow that broke

3) the castles on the appian way with the roses in May

4) the cupboard with the white fans

5) looking for pine kernels in Borghese gardens

6) riding on tiger skin

7) a particular mean nada Zigarnatan etc.8

The list provides a key to Jarman’s entire aesthetic. The manner in which the sparseness of his RAF beginnings caused a handful of objects to shimmer with such totemic potency that they acquired an almost magical allure is echoed down the years by his appreciation of single items of great beauty or personal significance, which he placed with ritualised care in all the spaces he ever inhabited, as well as in his paintings and films.

Rome crucially prefigured the future in two further ways. The flat was shared with a family of Yugoslavian refugees. While the children provided Jarman with playmates, the mother afforded him an early artistic example. When not at the kitchen table singing ‘rousing Yugoslav partisan songs’,9 Nada Ziganovitch10 (the ‘particular mean nada Zigarnatan’ of Jarman’s list) spent most afternoons combing the streets of Rome for a spot to erect her easel. In her footsteps followed a fascinated Jarman.11

Then came the afternoon his parents took him to the cinema for the first time, to a matinée showing for forces children of The Wizard of Oz. Because the outing interrupted the feeding of his tortoise, one of the few pets his peripatetic childhood allowed, he had not been keen to go, and there were moments that afternoon when he wished he had not. The film so utterly transported him that at one point he ducked under his seat ‘with a terrified wail’, then bolted, only to be ‘captured by the usherette and handed back along the row to [his] embarrassed parents’. The Kansas farm, the spiteful neighbour, Dorothy and her dog, Toto, the tornado that lifted her house clear into the sky, the glorious technicolour of what lay over the rainbow, Dorothy’s trio of friends, a yellow brick road, the Wicked Witch of the West and her frightening cohort of flying monkeys, a wizard who ‘frankly admits his incompetence’12 – the images were so real to Dekky that he would never forget their impact. ‘I took part 19in … [the film], rather than merely watched it, and am grateful to this day that it had a happy ending.’13

The wonder of gardens, aesthetic appreciation of a Latinate young man and of other objects of beauty, the power of painting, of cinema, wizardry and witchcraft – Jarman’s Italian sojourn was short but of great importance, providing him with a template, a ‘curriculum vitae Art History self portrait romance’, from which can be traced virtually his entire artistic future.

3

Buried Feelings

By 1947, although the war had been over for two years, its effects were still being strongly and unpleasantly felt in England. Despite victory and the determination of the recently elected Labour government to start a new social chapter in the country’s history, the process of adapting to peace was slow and painful. It is a mere detail, but not long after the Jarmans returned from Italy, Lance was invited to lunch at Blenheim Palace. That evening, Betts and the children were agog to know what it had been like. What had he been given to eat? The answer was distressingly simple: Spam.

The family had travelled back from Italy on a ‘storm-tossed troop ship’.1 With Bloody Little Joany still in attendance, they had gone to stay in Northwood with Moselle. They were not the only prodigals returning home. After a war spent presumed missing, but actually enduring unspeakable horrors in a Japanese POW camp, Betts’ brother Teddy was also back in Northwood, married to his first wife Pegs. Moyra was working for her flamboyant Aunt Doris in a boarding house behind Harrods, later moving to nearby Mount Vernon Hospital, where she would meet her first husband. For the first time in almost ten years, the Puttock family were reunited and 21able to bear witness to the after-effects of the war as they related to Lance.

Lance’s ascent through the ranks of the RAF was continuing unabated. On his return to England in July 1947, a month before his fortieth birthday, he had been promoted to group captain and given a posting to RAF Oakington near Cambridge, where he was put in charge of transport. Yet although the future held some exciting challenges, the particular excitements of youth and war were a thing of the past. Lance was now shouldering the responsibilities of a young family on RAF pay and in the bleak surroundings of life on the ‘patch’. Italian opulence had been supplanted by a mildewed Nissen hut ‘filled with thick suffocating coke fumes and running with … condensation’,2 Lake Maggiore by an old yellow dinghy on the lawn, smelling strongly of rubber and filled with hose water.

As Jarman later explained, with no forays to make into enemy territory, Lance’s temper, never placid, spilled into the domestic arena. The person with whom he most often clashed was his son; ‘so elegant’, according to his Aunt Pegs, ‘so full of fun with his little twinkle in his eye; a really go-ahead little boy’. Their fights were principally over food. Jarman’s persistent refusal to eat certain things maddened his father beyond endurance. It was the start of a titanic clash of wills. Though the father, with his military bearing, was the more obviously powerful of the two, there was an equal, if more subtle, thread of steel running through the ‘elegant’ son. Mealtimes became skirmishes that could also involve Gaye. The story is sometimes told about Jarman but, as Aunt Pegs remembers it, it was Gaye, then four, who was fiddling with the salt cellar when Lance told her to stop. She refused. Although it was winter, he lifted her out of the window and left her in the cold until sufficiently chastened. Then came the night Jarman’s ear was hurting. He was in bed, crying. There were guests for dinner. His wails disturbed them. Lance strode down the passage and beat the child until he fell silent. The next day, Derek was still in pain and the doctor was called. It was discovered he had an abscess in his ear which needed to be etherised and drained.

In the Puttock home-movie footage of a family meal, if one looks carefully one can see that the film is inadvertently running 22backwards: food is being regurgitated instead of ingested. The images we have of Jarman family life need similarly careful scrutiny if one is to appreciate the darkness lying behind a generally bland and blameless façade; to see that little Dekky was being traumatised by his clashes with his father; that doting Moselle sensed this and would never forgive her son-in-law for his actions; that it fell to the ‘always smiling Betty’ to keep the family peace, a role at which she became painfully adept over the years.

In January 1948, Lance was posted as commanding officer to RAF Abingdon near Oxford. Gaye and Derek were taken out of their school, Kimway, where they had spent only a couple of terms, and put into a local convent school, St Helen and St Katharine.

In an adult diary, Jarman provides a vivid account of life on the Abingdon ‘patch’. He skilfully sketches their desolate, camouflaged house, the uneven lawn bounded by barbed wire, the concrete rockery made from the remains of an old air-raid shelter. It is an account that encompasses both the normality and the chilling abnormality of the Jarman home.

In the corner of the garden some wild cats bred in a pile of logs, and I lay in wait to trap the kittens, which bit and scratched … the house next door had been bombed, the garden had gone wild, we’d play there … Dad took me out shooting rabbits and hares at night, by the headlights of his car on the empty airfield, I hated that – I starved rather than eat those rabbits. I was very difficult with food, virtually lived on suet pudding, ‘canary’ pudding, and of course I was very artistic. I drew endlessly, which was a great source of pride to my mother … flowers and Tudor villages, sunsets with geese flying, copies from biscuit tins … Plants fascinated me, I remember standing mesmerised in front of a huge horsechestnut in full flower in a field … I watched the tree grow until called home. In the evening my mother would take out her Vogue Pattern book and make clothes, she was always immaculately dressed, the most stylish of the mums, I was very aware of that … I was always asked to thread the needle in the Singer sewing machine … My parents would 23go out in the evening, and we would wait breathlessly to see them off. Mum appeared in her latest dress like a dazzling film star … Dad would be in his full mess kit. They were impressive, almost other worldly, at these moments … Living behind barbed wire, we were set apart, we knew we were different. I still feel this to this day … I don’t understand the sloppiness of civvy street. You see we clicked to attention when we had to. Dad was being saluted continuously … he seemed even more alien when the two of us took off alone, flying the Chipmunk trainer … playing hide and seek through the motionless cumulo nimbus clouds that hang above the butterfly fields of Oxfordshire. He frightened us with his sudden outbursts of violent temper, he would fix on some small mannerism … ‘hands in the pockets’ or ‘pardon’, that was belted out of me, often I felt terribly sad and dreamt of vengeance, but then mum seemed to love him so he had to be all right. I never unleashed my fury. I was too frightened, and later, as I grew up, my mother contracted cancer so we all behaved out of deference to her illness. We buried our feelings and stuck it out …’3

At Kimway School, Jarman had attained straight As. St Helen and St Katharine would report that while he took good care of Gaye, and his drawing and handwork showed consistent originality, he was too excited, restless or careless to do well at his other subjects. It was the start of a long and worrying scholastic decline in a child whose quick intelligence should have led him to shine. In Italy, he had become reasonably fluent in Italian, to the extent that Betts and Moyra had used him as an interpreter. Now, when asked by his parents to demonstrate his linguistic prowess at a party, this most performance-orientated of children, who loved nothing better than ‘to act things out’, was overcome by sudden shyness and found that the language had deserted him. His natural extroversion was transmuting into energy of a more jittery nature. He began to develop characteristics which would dog him for the rest of his life: a slight clicking sound in his throat when he talked, a restless hopping from foot to foot, a flapping of his arms. Although physically robust, he 24became gradual prey to a clutch of ailments usually considered nervous in origin: asthma, eczema and, for a while, hayfever. Two contradictory impulses, extroversion and introversion, were developing side by side in the boy, which is doubtless why, as a grown-up, despite being the most warm and open of people, and the least secretive, there would always be a part of him one sensed one could never know.

In January 1948, on turning six, he had to contend briefly with another convent: St Juliana’s in Oxford, within easy reach of Lance’s new posting to Kidlington.4 The nuns here were particularly gruesome: ‘automata’, Jarman called them, who ‘hacked my paradise to pieces like the despoilers of the Amazon – carving paths of good and evil to Heaven, Hell and Purgatory’.5 But a grown-up school was being sought, one which Lance, still intent on assimilating, hoped would mould his son into the sort of Englishman to bring credit to his parents. As Jarman put it: ‘After the war he [Lance] no longer played the piano or did other creative work. He just had to bury his whole past and this took a terrible toll on him. He retreated into a kind of shell … he became more English than the English, yet at the same time, he hated them. He turned my sister and me into middle class English product … We were part of his fitting in …’6

In early 1948, Jarman was accepted for the May 1950 intake by Hordle House, a family-owned prep school on the outskirts of Milford-on-Sea. In the summer of that year, as if in an effort to familiarise themselves with the area, the family’s holiday allegiance switched from prewar Bexhill to postwar Swanage. Swanage spelled August, a boarding house and – until she left to get married – Bloody Little Joany to assist if Lance could not get away. On the drive there, it meant passing Bournemouth, and ‘a prize of sixpence’7 for the first child to see the grey stone fingers of Corfe Castle pointing dramatically skywards, followed soon thereafter by a first glimpse of the sea sparkling in the distance between the Purbeck Hills. It meant an enclosed bay, a small, almost apologetic stretch of sandy beach, an old stone harbour bobbing with boats, a pier, a high street. It meant sandcastles, ‘buckets, spades and candy floss’,8 trips to the caves at nearby Tilly Whim, where ‘you could imagine yourself as a smuggler’,9 and bracing walks along the gull-haunted cliffs at Dancing Ledge.25

For Jarman, it was the start of a lifelong love affair with what he called ‘the twilit England’:10 that island within an island, the Isle of Purbeck, with its range of hills and sweeping stretch of down at Lulworth that tumbles to the sea in huge folds like petrified breakers; its bewildering tracery of winding lanes, small villages uniformly built of grey Purbeck stone and scattered, lonely farms; its patches of scrubby, blackened heath and gorse; its Ministry of Defence firing ranges; the village of Worth Matravers. In time, these places would come to signify a very personal geography, a geography of the soul; a map less of ‘twilit England’ than of the heart; a magical alternative to the often harsh and unpalatable realities of the outside world.

4

School House and Manor House

The fifties are frequently seen as an age of wide-eyed innocence. The Festival of Britain, a young Elizabeth, Supermac, net petticoats, Brylcreem, quiffs, salad days. They were also a time of great stress and unease – the end of empire, Cold War, Suez. One of the ways people coped was by pretending that nothing had changed. By turning their backs on the outside world. By clinging to old certainties. Nowhere was this more evident than in certain public schools.

Hordle House, Jarman’s prep school, and Canford, his public school, were in the business – and it was a business – of providing the country with future leaders. They believed this was best done by adhering to tradition, fearing God and encouraging manliness. In the clumsy-sounding Latin of the Hordle motto: Move Te Ipsum – Bestir Thyself! Though in Hordle’s case, sternness was tempered by genuine concern for its youthful charges; by a determination to foster an alternative ‘family’.

Since its inception in 1926, the school had occupied a brick-built, ivy-clad house bestriding some thirty acres of ground on the cliffs overlooking the Solent, the long low hump of the Isle of Wight and the three Needles.1 It is a particularly windswept part of 27Hampshire, and the house, into two wings of which, one senior, one junior, eighty boarders were crammed, could be extremely cold in winter. Existence there in the early fifties was fairly spartan. Rationing was still in force, which meant that despite the efforts of the school cook, the diminutive but doughty Mrs Monger, responsible for such delights as ‘Mrs Monger’s toenails: tough apple cores swimming in a sour translucent mush’,2 school meals relied heavily on bread spread with margarine and watery strawberry jam. On this meagre fare – supplemented only by what treats they kept in their tuck boxes in the Nissen hut on the front lawn, or their Saturday ration of sweets – the boys were expected to engage in a plethora of outdoor activities: football, rugby, cricket, rifle practice, squash, boxing, athletics and, thanks to the school’s location, sailing and swimming. Each and every day during the summer months the entire school would descend the cliffs. Avoiding the remnants of the squat, concrete tank defences on the beach, the boys would plunge into the sea, no matter what the temperature, while the long-suffering under-matrons stood up to their waists in the waves, acting as markers. If anyone was found shirking, or in any way misbehaving, it was off to the headmaster’s study to be tanned.

Anything less congenial to someone of Jarman’s sensibilities would be hard to imagine. The picture suggested by his arrival at the school in May 1950 is heartrending. A brusque father, a mother loath to be sending her son away so young, a sympathetic aunt. A sparsely furnished dormitory, uninspiringly named after one of the school’s founder members. Serried ranks of beds, and – since this is a junior dormitory – a teddy bear upon each pillow. Taking charge of the new arrivals, the fearsome Miss Barbara Nickal, known as Ma Nick, ‘a great grey bulk of musty pullovers and thick woolly stockings and steel-capped walking-shoes that clicked like the deathwatch’. Ma Nick lived at the top of the house and instilled such terror in her charges that she was rumoured to be a male German spy. The ‘cast iron hairstyle with steely ringlets’3 was, the boys whispered, a cunning disguise, the lighthouse on the Needles a sinister means of flashing coded messages to Ma Nick at night.

In this environment the otherwise bright and intelligent Jarman began to founder. He dropped to the bottom of the class. His lack of 28co-ordination became more acute, never more so than when in the grip of some excitement. Then, unable to keep still, he would leap around gesticulating wildly, much to the amusement, sometimes scorn, of his fellow pupils. The obligatory sports – boxing in particular – became an enormous trial.

He responded by withdrawing further into himself and by throwing himself with even greater absorption into his painting. ‘I started to paint in order to defend myself from this world.’4