Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Aniara

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

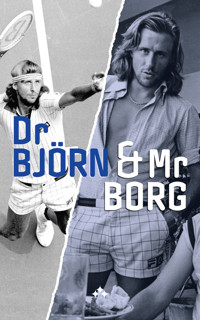

The definitive biography of one of the greatest tennis players of all time. Named Sweden's greatest athlete in history. Five consecutive Wimbledon titles. Six-time champion of the French Open. Björn Borg's record-breaking achievements on tennis courts worldwide left the world in awe, earning him the nickname "Ice Borg" for his almost superhuman focus and discipline. But when he retired at the age of just 26, the world was stunned. Top ranked and in the midst of an incredibly lucrative career, no one could understand why the champion walked away from the game for good. What really happened? Dr Björn and Mr Borg: The Unauthorised Biography is the true in-depth biography of this Swedish sports legend. Author Jan Söderqvist delves into the complex duality of a man who, through sheer willpower, transformed himself into an unbeatable tennis machine, but who later risked losing everything he had achieved through a series of disastrous decisions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 743

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dr Björn and Mr Borg

The Unauthorised Biography

Jan Söderqvist

Contents

Instead of a foreword by John McEnroe

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Literature and Sources

Instead of a foreword by John McEnroe

Things rarely turn out exactly as you expect them to. This is true both on the tennis court and in life in general. You start with something and then end up with something completely different, something that could not have been foreseen at the beginning of the process, but which takes on a life of its own and develops according to its own built-in agenda. Books live a life of their own during the writing process; one thing leads to another, and just like a tennis match, it usually goes through many different phases on its way from start to finish.

At first I had no intention of writing this book at all, but after many conversations with my enthusiastic publisher Claes Ericson I changed my mind and set to work – tentatively and cautiously at first – with my head full of more or less hazy ideas about what sort of book I actually wanted to write. And the main reasons I changed my mind were partly that Claes spoke so persuasively about the need for a book about Björn Borg, and partly that he was quite simply right. There is not, and has never been, any comprehensive book written about Björn Borg – focused precisely on Björn Borg and nothing else – this despite the fact that Björn has been voted by sports-minded Swedes as our country’s greatest athlete of all time. This is unfortunately still true today, in the fall of 2025, after Björn Borg's own "autobiography" Heartbeat – told to his wife Patricia – has been published. The problem with this book is that it’s highly reticent regarding the sex, the drugs and the rock'n'roll. As well as about the money and everything interesting. It's a self-produced fluff piece. And it’s poorly written. His prematurely abandoned career was utterly magical. And the fact that there neither is nor has been any remotely decent book on the subject is quite frankly nothing less than a great, fat scandal. This simply won’t do, I thought – and surely Björn himself shouldn’t want it this way either. There are fine books about, and in some cases by (albeit ghostwritten), virtually all the great tennis stars, both past and present. Why should Björn Borg alone be the exception? It can hardly be because his story lacks either drama or glamour.

So without reflecting too closely on the matter, I imagined that Björn would actually cooperate with me. That he would play ball, as they say in that sporting metaphor. He would want to say what there was to say, and he would want to own his own story. And what could be more natural than a grateful foreword signed by John McEnroe, who was Björn Borg’s enthusiastic rival and, moreover, his successor as world No 1 in tennis? I would arrange that – I had a way in. Or at least the email address of John McEnroe’s agent at IMG. McEnroe has, after all, spoken so many times about how his rivalry with Borg lifted his own game and lent lustre and glamour to the entire sport for many years. And I would make it so easy for him – and therefore so hard to say no.

He wouldn’t even need to write his foreword if by ’write’ one means actually holding a pen to paper or tapping away at some keyboard; I could easily ghost-write it for him myself after an interview or two, preferably conducted during the French Open, when many of yesterday’s stars tend to be on hand as expert commentators or simply as initiated spectators mingling with each other and sponsors, perhaps hitting a few balls with some corporate executive. In all humility, I thought McEnroe would actually bite at this offer, and that people would actually think he wrote almost as well as he played tennis. That was exactly how I pitched my proposal to his agent: I do the research, I interview and write, Mr. McEnroe need only read through and approve, after which he can collect both fee and astonished applause. So I crafted what I thought was a punchy little sales pitch and fired it off in an email to his agent. What did Mr. Agent think? Was it an acceptable proposition?

The agent, called Gary Swain, replied to my email straight away via his phone. He was, he told me, obliged to check first how Björn Borg himself felt about this project before he could put my request to his client. Which was logical, I realised on reflection. Both Borg and McEnroe are represented by IMG and decisions on matters like these, essentially commercial in nature, are naturally coordinated as a matter of course. I read Gary Swain’s email just before my flight to Italy (where much of this book has been written) departed from Stockholm Arlanda. No problems and no rush, I replied. I’ve been in touch with Björn and hope for an answer shortly. I’ll get back to you then. When I landed in Pisa just over two hours later, Björn’s reply had already arrived and I now knew how he viewed the matter. Admittedly, he hadn’t responded quite as lightning-fast as Gary Swain at IMG, having taken a few days to consider, but one can hardly fault him for that.

And the answer was as brief as it was clear:

Hello!

Thanks for the enquiry, but I’m not interested.

Björn

And there it was. Which at first smarted a little, perhaps. No participation from Björn’s side, and goodbye to the foreword by John McEnroe. But soon enough I grasped two things. The first was that Björn Borg would naturally keep well clear of a project like this. There simply isn’t much upside for him, and it’s not as though what he needs in his life is another small dose of fame. He’s not interested in books and doesn’t care that there are sharp biographies and such about all the other stars – he’s probably never read them. My second insight was that it was actually liberating. Now I could write exactly as I wanted without having to feel bound by any stated or unstated loyalty to a person who (in that case) had made himself available to me and shared his time.

There was, I realised at an early stage, a certain risk that at least some chapters would not prove entirely flattering to Sweden’s greatest sportsman of all time. And it was also evident that Björn’s primary purpose in interviews has always been to protect his own brand at all costs – the brand that appears on underwear and bags and has over the years generated large sums of money for his own pockets, albeit often via convoluted tax-minimising detours through various offshore companies.

Therefore, organised collaboration would most likely have cost more than it was worth for me, probably in more ways than one, since Björn would perhaps – probably – want a substantial share of the book’s earnings. And why shouldn’t he want that, for that matter? It’s naturally more on his name than on mine that the book sells, insofar as it sells at all. He knows, just like John McEnroe, that his name is still worth serious money. He tends to talk about it; only the other day I heard an anecdote from a dinner quite recently where Björn joked that he would sign a thousand-kronor note belonging to one of the other guests, but that he couldn’t possibly do it because the note would then be worth a ridiculous amount of money.

So now I can be seen as either being hypocritical and making a virtue of necessity when I claim to be perfectly content that Björn Borg wants nothing to do with this book, or one can recognise that David Remnick, editor-in-chief of The New Yorker, actually has a point in saying that nothing is more overrated than meeting and conversing with the subject of the portrait one has been commissioned to write. It is all too easy to drown in access and plumb the depths of banality, trussed up with ropes woven from a more or less imagined camaraderie.

Which isn’t to say that I’m in any way lacking in admiration for Björn Borg’s achievements on the tennis court. Good Lord, one could argue that they speak for themselves, but I’d say they appear even more extraordinary the more you delve into what he actually accomplished and under what conditions. Just how admirable his performances truly were is something I hope will become clear throughout this book.

But Björn Borg is fascinating in so many aspects beyond the purely athletic. He became a tennis star during a period when tennis was making its serious entrance into television media, which meant that big money was seriously entering the sport through advertisers and sponsors. This in turn meant that he was exposed to public attention like few other sports stars during an intense period and was given the opportunity to earn enormous sums.

From a Swedish perspective, this becomes particularly fascinating because these unprecedented achievements stirred decidedly mixed feelings in the nation. On the one hand, we were proud that a Swede had climbed to the very pinnacle of glamorous tennis. We liked to imagine that this happened by virtue of what we see as typically Swedish virtues – diligence and discipline, willingness to train and make great sacrifices. On the other hand, it troubled us – or at least troubled large sections of the Swedish press – that in 1974 Björn felt compelled to move to Monaco to minimise the tax burden on his steadily rising income, and that he subsequently did not always wish to speak to Swedish journalists when certain members of the corps had highlighted this breach of etiquette.

Was he one of us ordinary Swedes, or was he nothing more than a calculating tax dodger who saw himself as above the rest of us and shirked his responsibility to contribute to the people’s home that had raised him and given him the chance to hone his craft in his sport?

Then there’s the spectacular bankruptcy of Björn Borg Design Group and all the twists and turns surrounding it. We have the much-publicized and in many ways fateful pill overdose in Milan in 1989, an incident widely reported as a suicide attempt but which Björn himself maintains was merely a case of ordinary food poisoning. We have the partying, we have the helicopter rides and the tragicomic comeback attempts. We have the divorces and all the media coverage about them, we have the scandals and the legal proceedings. And so on.

Given all this, it is neither more nor less than a mystery that there is not a single book focusing entirely on the phenomenon of Björn Borg.

Good heavens – what actually exists in print about Björn Borg? We have, to begin with, the ‘autobiography’ Till hundra procent (To one hundred per cent) from 1992. Here we are told, according to the back-cover blurb, about ‘the bitter experiences of the press’s vilifying articles and the weekly magazines’ relentless surveillance, which reaches right into the bedroom’. We are further promised a personal account of the women and family – ‘Björn Borg remembers and tells personally about Mariana, Jannike and Loredana and others who have crossed his path’. And ‘at the tape recorder’ sit the lawyers Henning Sjöström and Lars G. Mattsson, two gentlemen who were, one might say, relatively untested as authors. Sjöström was, however, Borg’s legal representative in the libel case against magazine Z, which Björn won, but where he later admitted he had lied about his use of cocaine.

And he continues to bend the truth in his autobiography, presumably with Sjöström’s blessing. At any rate, Björn was plainly satisfied with his lawyer – this emerges in numerous places throughout the book, where he repeatedly speaks of Henning ‘who had done an incredible job’ and ‘thanks to Henning we won the case’, and so forth.

One can try to imagine that Björn really did nag away about how all these tributes to the lawyer absolutely had to remain in the printed text, despite the humble Henning no doubt fighting valiantly to edit them out. But the question is whether it was Björn or Henning at the tape recorder, or both, who insisted at any price on keeping the revelation that our great tennis champion believes in UFOs. Or which of the two felt that the account could not survive without the information that Björn constantly harboured the ambition ‘to be the best at shagging’.

Apart from this autobiography, there is really only one other title worth mentioning in this context: an interview book from 1980, published with Björn himself as ’author’ and compiled by the American Gene Scott (himself a successful tennis player during the 1960s; he represented the USA in Davis Cup and founded the magazine Tennis Week): My Life and Game. Considered as a book, it is not without interest – it provides various insights into how Björn thinks about his game and about the circus around him when he finds himself at the height of his career. It came out just before that dip in the rankings which resulted in Björn throwing in the towel at the age of just 25. Scott, who died in 2006, knows what he is talking about, and he gets Björn to talk in reasonable detail about how he operates on court, about tactics and strategy. And about how much he dislikes journalists, about the pressure of constantly having to win matches, and about how much he gets paid by his many sponsors.

But fundamentally this is a piece of propaganda, a eulogy that constantly emphasises what a likeable and thoroughly exemplary sportsman Björn is and how incredibly popular he is amongst all the other players (which is not entirely true). So whilst Scott’s book definitely has its merits for anyone wanting to approach the tennis player Björn Borg, it is completely useless for anyone wanting to understand anything about Björn Borg as a media and popular culture phenomenon at a particular time under particular circumstances, just as it has nothing at all to tell us about how his existence took shape after his prematurely ended sporting career. When it was published, Björn imagined he would continue playing at the highest level for at least another five years – so it was not to be – and after his career ended he intended to settle in Florida. So it was not to be either. At that point Björn cannot have been entirely clear about the tax implications of settling permanently in the United States.

That Björn himself would wish to contribute to shedding light on much more than his sporting achievements is hardly to be expected, since not all details would be to his advantage, and details that are not to his advantage are nothing he cares for – that is what foolish journalists busy themselves with. And thus, I soon realised, there would be no foreword from John McEnroe either. My exchange with Gary Swain fizzled out. On the other hand, it is entirely possible to reconstruct such a foreword, at least in broad strokes, since John McEnroe has spoken about his Swedish rival countless times; it would be strictly pointless to trouble him with repeating the same things once more just so I might have a foreword (and a crowd-pulling name) for my book. There are deplorably many interviews, not least in sporting contexts, that consist of regurgitation of reheated scraps in the form of commentary on, and more or less contrived new variations of, old interview answers. Such stuff is simply degrading for all concerned.

At the same time, John McEnroe is and remains absolutely indispensable to me if I am to say anything essential at all about the tennis player Björn Borg. He and the rivalry between him and Björn are perhaps the most important and central elements in at least the first part of this story. It was in the matches with McEnroe that Björn was put to the severest tests and forced to elevate himself to the highest levels simply to keep pace. It was John McEnroe who drew the very last from him and who, more than anyone other than Borg himself, defined his unique qualities as a player. It was alongside the almost otherworldly gifted John McEnroe that Björn’s greatness as a tennis player emerged with the greatest clarity.

It is certainly true that Björn had other formidable rivals besides McEnroe, most notably Jimmy Connors and Guillermo Vilas perhaps. But in those cases it was Björn who was the rising supertalent on his way up, whilst Connors and Vilas were the established top players who, after many hard battles, were forced to abdicate from the throne and accept that they were no longer the best in the world. With McEnroe it was different – he was the younger talent hunting Borg from behind, and who eventually succeeded in dethroning the Swede, who was, if anything, even less interested in standing in someone’s shadow than the utterly victory-hungry Connors was. To be ‘merely’ world No 2 after having previously been No 1 for several years held no appeal whatsoever for Björn. To continue training so mindlessly hard and living so disciplined and monotonous a life as tennis at international top level demanded and demands, only to then regularly get thrashed by John McEnroe in the big finals – that was a scenario which over time seemed increasingly unbearable for the still young Swede.

Admittedly, Björn was fond of money, and by staying on the tour after his years at the absolute peak – like Connors and later McEnroe (and now Roger Federer) – he could have pulled in enormous sums, both in prize money and even more through lucrative sponsorship deals and exhibition matches. But in his case, I believe, it was the will to become and remain world No 1 that was the necessary driving force for him to endure all the monotonous grind, day in and day out, week in and week out. When Björn realised that the younger McEnroe had caught up with and overtaken him, that he simply didn’t have the weapons in his arsenal needed to defeat his rival when it really mattered, then it was no longer fun. Being world No 2 without reasonable prospects of reclaiming the top spot was a drag. Not sufficiently fun to motivate him to continue with a hundred per cent commitment to tennis and nothing else, with all that entailed of asceticism, sacrifice and brutal discipline – particularly not now that he had developed a taste for other things, chiefly through the American Vitas Gerulaitis, who was reluctant to let important matches interfere with his energetic partying and who for a long time had the physique to sustain that lifestyle. It is therefore not unreasonable to argue that John McEnroe was both the one who lifted Björn to fantastic heights as a player and later also became the one who brought his tennis career to a remarkably early close. He was too good; he simply won and won all the time. And then it was no longer fun. Then it was enough for Björn, and then it made no difference that there were masses of money still to be earned. And yet Björn was hardly one to turn down the money that was offered without hesitation.

For McEnroe, the virtuoso talent who had come from below and overtaken his idol and mentor, it was enormously satisfying; defeating Björn Borg was uniquely fulfilling for him, and a match against Borg was what he looked forward to above all else. He was entirely clear about what their rivalry meant not only for him in that it forced him to exert himself to the very utmost to win, but also for the sport as a whole, since the media seized upon their recurring duels, generating reams of coverage and speculation, which in turn generated greater interest in the major tournaments.

Björn made him a better player, and a rivalry like theirs – between two fundamentally different temperaments and playing styles – elevated the entire sport and underscored how perfectly suited tennis was to the television medium, where close-up cameras and sensitive microphones positioned down by the court’s lines could create the illusion that viewers really got to know the players’ personalities. Who would emerge victorious from that uncertain duel this time? The inscrutable Swede with his rolling gait, his dogged stare at his own shoes, his rigid facial expression utterly without variation that signalled total control? Or the sullen American with his lightning, unorthodox attacking game, his constant outbursts of fury with yelling and screaming at umpires that signalled total collapse was perpetually imminent practically the entire time?

But suddenly the duels were no longer uncertain, and the inscrutable Swede no longer wanted to take part. He didn’t want to keep losing. He stopped playing tennis. Or competing, at least. For McEnroe, the entirely unexpected decision was a devastating blow. He could neither understand nor accept it. He’d had a Björn Borg poster in his boyhood room (right next to a Farrah Fawcett poster), and he’d been a ball boy to his idol when the Swede played the US Open in 1972 – that is, when the tournament was still held at Forest Hills (the American was 13, the Swede was 16). ‘Then to succeed in playing my way up to the world elite when Borg and Connors were No 1 and No 2, and to get to be part of all that – it was like having your dreams come true, and it felt as if tennis was at its absolute peak,’ McEnroe has said in interviews. But ‘that Borg decided to quit was one of the biggest disappointments of my career’.

So he tried to persuade Björn to change his mind: ‘Playing tennis is all we know’’ he would say. But Björn simply shook his head. He had made up his mind and nothing could make him reconsider. There was no motivation left. He had no desire to acknowledge his defeats. His pride could not bear it. Up to this point, he had known that under normal circumstances he could beat anyone with his almost otherworldly ability to chase down and return virtually every ball. He always had an answer to everything, could handle all playing styles. He was called ‘Houdini in a headband’ precisely because he never gave up, always kept grinding away and wriggled out of seemingly hopeless situations.

In almost every tournament he was, often in the early rounds before he had properly accustomed himself to the surface and conditions, on the verge of being knocked out by some wildly aggressive opponent with an inferior ranking (a seeded player always faces lower-ranked opponents in the opening rounds, players who have nothing to lose and who have powerful incentives to take risks), but in the end it was always Björn who triumphed and advanced to the next round. He never grew tired, at least not visibly, he simply played on and won. But against John McEnroe he could no longer rise to the challenge.

Being world No 1 is a burden – you are constantly hunted by everyone else and therefore under constant pressure, and being on the rise is always more enjoyable than frantically defending your top spot or, worse still, sliding down the rankings – McEnroe felt the same way, at least in hindsight. The two best years of his own career, he said later, were 1979 and 1980, when he was chasing Borg and Connors ahead of him. He loved being the new boy, the tormented prodigy who threatened the established stars, whilst they shielded him from fame’s most merciless spotlight. He thrived best in the shadow of his elders and was grateful to escape the pressure of representing the entire sport of tennis himself.

When Björn gave up competing, he left McEnroe alone at the summit where the wind blew so mercilessly hard. And with Björn out of the game, there was no longer anyone McEnroe respected as much. ’I thought that together we would pull each other up to those unreal heights,’ the American said of the Swede. ’And then he just went and quit like that.’ It took McEnroe several years to recover from this sufficiently to motivate himself to raise his own game further, but now without that pull from Björn. During the first years without his Swedish rival, he was angrier than ever. All along he hoped that Björn would change his mind and return to tennis.

One might, as Tim Adams does in his book On Being John McEnroe, question whether Borg’s sudden absence didn’t deprive the American of a necessary opportunity to constantly reclaim his self-respect. The perfection McEnroe strove for was, he felt, only achievable in matches against Björn Borg. Their on-court antagonism was what made his own efforts feel meaningful and what made him feel like a complete person. When asked how he thought their matches would have gone if Björn had continued playing, McEnroe replied that they would probably have continued to stimulate each other to become better and better, not just as players but also as people. That was not to be. With Björn’s retirement, the opportunity vanished for both of them to spur each other on to development in both spheres. Whether McEnroe became a better human being is unclear, but after a few years of drift he pulled his tennis together and in 1984 could boast a wholly matchless record: 82 singles victories against just three defeats. All while Björn occupied himself with other pursuits. With varying success.

In his memoir Serious – and I repeat again with sceptical frustration that there is, quite simply, no corresponding book about Björn Borg – John McEnroe recounts that during a problematic phase of his career he seriously considered approaching Björn’s former coach Lennart Bergelin about a possible collaboration between them, but that it never came to pass, partly because he was afraid that Björn would disapprove, and partly because deep down, for the longest time, he believed and hoped that Björn would return to tennis. Björn was, after all, the one who – together with Vitas Gerulaitis – had initiated him into the art of living like kings and enjoying a life of high living out on the tour. And McEnroe always behaved himself during matches against Björn, quite simply, he writes himself in Serious, because he respected his opponent too much to allow himself to lose his composure and berate the umpire. How could the man stop playing tennis? He was only 25 years old! All right, he may have been ’only’ world No 2, but a clear‑cut No. 2 who had beaten Connors time and again in succession, and in the big tournaments anything can happen, writes McEnroe. He himself could have a bad day and take a loss before the final, so Björn could face someone else. Nothing was in the least predetermined. To simply pack up and leave the stage when he was still so close to the world No 1 spot seemed like sheer madness.

Yet even as he acknowledges this, McEnroe launches an alternative theory. Björn had simply had enough. He had begun his career so early and had been so successful, which partly made him exhausted and bored now that he was no longer number one, and partly had made him the first player in tennis history who could afford to withdraw from the tour at such a young age and live off the money he had amassed and the accumulated advertising revenues. His tennis life had become regimented to such a degree, something reinforced by his superstition – everything had to be repeated in precisely the same way, year in and year out, same hotel, same meals, same car, same route to the arena, same tracksuit top in the final, et cetera in absurdum. But now he had, as mentioned, acquired a taste for another life, largely thanks to the legendary party animal Gerulaitis, Björn’s closest and perhaps only real friend on the tour. It was women and partying all night long.

Björn had, McEnroe recounts, begun to allow himself these indulgences in small doses during the razzmatazz of exhibition matches around the world, but never when it came to proper tournaments where vital ranking points were at stake. And now, as the eternal grind of training, the regimented sleep and the strict diet appeared increasingly repugnant, other things beckoned all the more.

Björn Borg is, writes McEnroe, a pronounced double nature, a Jekyll/Hyde figure: on the one hand an ascetic monk-like character with unique willpower and the ability to master his own impulses and screen out all distraction in order to achieve the goal he has set for himself; on the other hand he is ’completely insane’, a party monster without equal, partly self-destructive. Moreover, he is governed to such a high degree by his pride, which leads to the fact that once he has declared publicly that he is quitting tennis, it becomes impossible for him on grounds of prestige to change his mind. It has never, McEnroe believes, been a simple matter for Björn to admit that he might have made a mistake.

Even at this early stage, it should perhaps be added that the dual nature McEnroe alludes to – exemplary conduct in sporting contexts alongside various painful crashes in civilian life – is really nothing unique to Björn Borg. Nor is it anything to be surprised by. It is important to remember that sport is, in fact, just sport: inexhaustibly interesting in itself, certainly, but not a metaphor for or guiding principle in real life. One cannot be translated into the other; sporting feats are performed under entirely different conditions from significant achievements in other kinds of professional activity. The rules within sport are clear and unyielding, to begin with. Whoever wins the most games in the final set also wins the entire tennis match. You must take the ball before the second bounce, you cannot hit into the net or outside the lines of the other half of the court – that is really the whole thing.

The element of brutal yet in some sense fair meritocracy is considerable, and you can really only speak of bad luck if you happen to get injured when you’re in the lead. It’s simply ridiculous to say anything other than that whoever played best won the match. In life outside the sporting arena, it’s more complicated. You might be the best salesperson in your entire industry, for example, but you can still fall victim to various kinds of office politics and get the sack whilst your equally incompetent but sycophantic colleague is praised and promoted. There’s no clarity, and people bend the rules all the time. There is, one might say, no justice.

Björn Borg believes – or believed at least while he was in the thick of his tennis career – that the athlete’s lot is harder than others’, that the pressure he lives under is incomparable. Ordinary people don’t have the attention of the entire world focused on them when they work. Even practitioners of artistic professions can count themselves lucky, he thinks. ’The conditions for a painter and a tennis player are completely different’, Björn tells Gene Scott in the book My Life and Game. ‘The artist isn’t judged in the same way. He doesn’t win or lose almost every day as we do: Picasso didn’t have a 5–3 match record against Van Gogh [sic]. But I have to live with my 5–3 against McEnroe and try to hold my ground’.

There is quite a bit to say about this. First, we must probably acknowledge that Picasso had roughly a 888–1 head-to-head record against van Gogh, who during his lifetime managed to sell one single painting (according to documented records). That the latter’s reputation improved posthumously hardly seems relevant here. Second, it is entirely true that the razor-sharp and by definition utterly decisive difference between victory and defeat in an important tennis match can in practice be a matter of extremely small margins, but the tennis player, by contrast, never risks being rendered unfashionable and discarded for unclear reasons by capricious taste-makers. If you have, like Björn, won Wimbledon five times in a row, then you have. Your name stands there in the history books for ever, and no one can claim that it is unfair in any way.

But there are other things in life besides sport, some might argue. Precisely. But all those other things can prove just as hard to handle as any hard-serving Americans on the far side of a tennis net. Perhaps harder. Björn Borg was once called ‘the perfect tennis machine’ by one of IMG’s agents. This is the story of that machine’s many extraordinary triumphs within given parameters, and of a series of dramatic breakdowns out in difficult terrain partly shrouded in fog. This is the tale of a remarkable tennis player, Sweden’s greatest sportsman of all time, and an endlessly fascinating double nature: Dr Björn and Mr Borg.

It was roughly this that I wanted John McEnroe to write in a foreword to this book, which would constitute a suitable starting point for the reflections on the intricate and partly enigmatic double nature of Doctor Björn (who spellbound a whole world with his unprecedented determination and exemplary behaviour on the tennis court) and Mister Borg (who – amongst other things – made a great many creditors very unhappy in connection with a spectacular bankruptcy, sabotaged himself with lawsuits and scandals, and crashed a number of marriages and other relationships) that follow. That won’t happen now, but it’s not necessary either. Fortunately, McEnroe has already written and said precisely this in other contexts, and it’s rarely more entertaining when you ask someone to repeat old statements. We have his deep and entirely reasonable reverence for the successful Doctor Björn; we also have his uncomprehending amazement at the self-destructive Mister Borg. That will be our starting point.

ChapterOne

It was infernally hot in London during the early summer of 1976. Over 40 degrees most every day. Out at Wimbledon, where, as always at that time of year, the world’s premier, most prestigious tennis tournament was being played, hundreds of spectators were said to have fainted. No rain at all, which is extremely rare, as all tennis fans know. On Tuesday 22 June, the heat was almost ridiculous, I remember. I had travelled up by daytime train from the seaside town of Hastings, where, at the age of 15, I was on a language trip. How I managed to get a ticket to Wimbledon’s centre court I don’t remember, but there I was, sitting in the sunshine, ready to watch Björn Borg take on American Marty Riessen in the second round after easily dismissing Briton David Lloyd in the first with a 3–0 set win.

Lloyd spoke after that match about how surprisingly well Björn had served. There was no getting at the Swede anywhere. And the thing about the serve was right. It was better. It was actually new, a new motion. 1976 was a special year. Björn had lost in the French Championships in the quarter-finals – to Italian Adriano Panatta, the only player ever to beat Björn in Paris – which gave him extra time to prepare for Wimbledon. Which he himself realised he actually needed to do. Above all, he needed to serve better.

Tennis on grass is something entirely different from tennis on clay, not only because grass is a living and therefore changeable surface, making the courts completely different at the end of a tournament, when they are worn and the underlying, hard-packed earth shows through, compared to the lush green of the opening days. But the bounce is also faster and flatter, which means shorter rallies, which in turn means that players run shorter distances. You must take the ball earlier, with a shorter backswing. And above all you must serve hard and reliably, since you must reckon that your opponent will get good value from his hard serve – after all, we are talking about the world elite here – and thereby win his service games more easily than would be the case on clay. On a clay court the ball bites into the surface for a fraction of a second and bounces more straight upward, which gives the receiver more time to react and prepare his return.

If your own serve isn’t a deadly weapon, you’re vulnerable on grass. You must also have a distinct, effective volley. That’s how you win points in your own service games (that is: if your rock-hard serves come back at all), and if you can only manage to lift over loose sitters, your opponent will mercilessly punish you as you stand there at the net.

All of this was to Björn Borg’s unequivocal disadvantage. In 1976 he was indeed seeded fourth, but no one believed he would genuinely be a serious candidate to take home the title. He was, they said, a typical clay specialist. His game, built on fabulous footwork, inexhaustible running ability, expansive movement and an almost eerie ball security, seemed perfectly adapted to clay’s interminable rallies on the slow surface, but virtually doomed by definition on grass where brutal attack was considered the only viable recipe for victory. And that reasoning was hardly unreasonable. Björn had achieved his great triumphs on clay, having won the French Open as early as 1974 as a 17-year-old, but on grass his credentials were less luminous. To no one’s surprise, in 1975 he went out in the quarter-finals after losing to eventual champion Arthur Ashe. But now, in 1976, it would be a different kettle of fish. And above all, there would be careful and methodical preparation.

Björn’s coach, Lennart Bergelin, had voiced frustration that his charge arrived jaded and with far too little time for grass-court preparation at Wimbledon. And perhaps that was hardly surprising; even though Björn was barely 20, he had already made it his habit to win the French Open at Roland-Garros in Paris, which meant that time for grass training shrank drastically. That Björn was also keen to play lucrative exhibition matches during what little time was actually available made matters no better. Perhaps this was part of the explanation for why his results in London still fell well short of those in Paris, where Björn would typically arrive after a well-executed clay season. He had not allowed himself the time and conditions required to compete with the very best on grass.

That it all came to pass as it did was in some measure thanks to Guillermo Vilas. His team was searching for ideal grass courts in the London area to prepare him meticulously for Wimbledon. What they managed to find for him was The Cumberland Lawn Tennis Club in Hampstead, north of central London. When Vilas’s intended sparring partner dropped out for one reason or another, the invitation went to Björn Borg and Lennart Bergelin. And the four grass courts at the small, well-maintained Cumberland offered perfect conditions. The very best thing from Björn’s point of view was that here he could train even when the courts happened to be a little damp from rain, which was absolutely forbidden at the tournament venue, where the organisers were quick to pull covers over the courts the moment a raindrop fell to prevent damage to the grass. And should it pour with rain, Bergelin had as a precaution booked reserve courts indoors at the Vanderbilt Club; nothing was left to chance.

The fact was that The Cumberland suited Björn so well that he chose to return and repeat essentially the same procedure throughout all the years he subsequently played at Wimbledon and in professional tennis generally. This had, admittedly, a great deal to do with superstition as well. If there was anything new that proved to work, or just some more or less insignificant routine that was performed in connection with a tournament victory, Björn was extremely keen that the pattern should be repeated as exactly as possible: the same thing in the same way, no changes at all, year after year. Train at The Cumberland, sleep and rest in a large suite with two bedrooms and a kitchen at the Holiday Inn Swiss Cottage right next door, girlfriend and eventually wife Mariana at the stove, the odd restaurant visit, always the same old routine after that first Wimbledon triumph.

Once the tournament was under way, Björn travelled with Lennart Bergelin and Mariana always along the same route, always in a Saab (which happened to be one of Björn’s sponsors). Bergelin drove so that Björn need not waste any attention whatsoever on anything other than his own tennis and the match that awaited. Mariana sat in the back seat. And his parents were to watch Wimbledon finals in odd years and Paris finals in even years, since this was considered lucky, because it coincided with how it happened to turn out in connection with the first tournament victories. Mum Margaretha would eat sweets during the final so as not to court misfortune. There is an anecdote about how in a final against Roscoe Tanner in 1979 she spat out her sweet when Björn had three match points since she then believed that everything was done and dusted and that her sweet had done its bit, whereupon Björn promptly lost three points in a row, which caused Margaretha Borg to hunt down the toffee where it lay on the floor of the players’ box and pop it back into her mouth. Which was all that was needed: Björn won two points quickly and with them the entire final and the entire tournament. It should be said that Bergelin was every bit as superstitious and renowned for a pair of lucky long johns with tigers on them.

On the grass courts at The Cumberland, Björn could work on all the small and slightly larger details that needed improving in peace and quiet, hour after hour, without being disturbed by anyone or anything. And first and foremost this concerned the serve. It was primarily about adjusting the position of the feet and changing the ball toss for a more forward contact point, which allows you to get your body weight behind the shot, which in turn gives better bite, more power, higher pace and a natural forward movement into the court. At least two hours a day Björn practised his serve alone. It is utterly mind-numbing monotony. Even Vilas’s coach, the Romanian Ion Țiriac, was dissatisfied with his player’s serve. So he tried by every means to sharpen it whilst Björn was grinding away at his.

The grinding was necessary, however. On clay Björn was considered virtually unbeatable, despite Panatta’s feat in Paris. The Hungarian Balázs Taróczy often trained with Björn, who defeated him twice at the French Championships, even though Taróczy felt he was playing at his absolute highest level. ‘In my eyes Björn was like a god,’ he said. ‘I was just unlucky to meet him of all people! He was truly too good, plus I, just like everyone else, had so much respect for him. Even if he played badly, I don’t think I would have had a chance. Borg had a feeling that he would win somehow, no matter what happened.’ But this crushing superiority on the slow surface did not make Björn seem a certain winner on Wimbledon’s grass – quite the opposite! Many have testified to how during his first training sessions on the new surface he looked like a beginner.

Chris Bradnam, a coach at The Cumberland from 1994, has told of how the older club members – keen amateurs – used to sit and seriously assess their own chances against Björn Borg. They reckoned, not infrequently, that they would give a decent account of themselves, so appallingly did Björn always play during his first days after arriving from Paris. He was simply dreadful and sprayed balls everywhere. But if you sat on a while and watched the training, you could also see how he steadily improved, noticeably, with each passing hour. It was simply a matter of hard work that had to be done and a willingness to submit to even the most monotonous drills – serve after serve after serve for hours on end.

John Lloyd, a successful tennis player (long married to the top-ranked women’s player Chris Evert), has said: ‘The funny thing about Björn was that when you saw him enter a tournament he was like a machine, yet he was absolutely dreadful during the first three or four days of practice on grass. When I suggested this, people thought I was on drugs. He couldn’t get his ball-striking right, so you’d think “Bloody hell, I’d love to meet him in the first round”. He needed time to adjust his technique from clay to grass. A bloke like McEnroe or Henman goes out on the grass and it literally takes no more than a few minutes for them to adapt. For me at my level it only took between five and ten minutes. I understand the bounce is lower, I know you have to use shorter racquet movements and that you have to follow through longer in the ball-striking. Piece of cake. But it wasn’t like that for Borg. He had to work incredibly hard during his training, but that was just how he was.’

As I said, all this hard work paid off – as it often does for Björn’s. He was prepared to train harder and more than anyone else, and his physique was exemplary. His opponent in the first round, David Lloyd, naturally had the utmost respect for the Swede, who by now was already a two-time Roland Garros clay court champion. But this was grass, and Lloyd considered himself a reasonably good grass player and thought he had a good chance of advancing to the second round. But he had no chance at all. ‘All I remember,’ he said afterwards, ‘is that every time I had an important point to play on his serve, he kept hitting his first serve. Boff! It went straight into the corner. He had an incredible first serve. It was heavy and with an extremely low error rate. If you analysed his game, at the beginning he could barely hit a volley, but now he was coming to the net after hitting groundstrokes that took you way out of bounds, and all he had to do was push the ball over the net.’ But all this serving also came at a price.

1976 was the year when Björn – having tried three times as a senior – finally cracked the grass code, as John Lloyd’s somewhat over-optimistic brother David was the first to realise. Their first-round match began an unrivalled winning streak that would not be broken until more than five years later, when he won an almost unbelievable 41 matches in a row. Many times he was in terrible trouble, but he was as stubborn and persistent as they come and refused to lose; the king of clay established himself as the king of grass. He made the necessary adjustments to his game, improved the strokes that needed improvement; but at the same time he remained true to his own style of play in all essentials, thus changing the way the whole tennis world looked at grass. He showed that it was possible to win points from the back court even on grass, that it was possible to build a winning game mainly on safety. It was still his footwork and superior physicality that gave him his edge and won him the even matches. His speed meant that he usually had several options when it came to choosing his shots. And his quick feet meant that he could stand well behind the baseline when receiving his opponent’s serve and still manage to cover all angles. Moreover, thanks in large part to his exceptional fitness, he was able to play a match when he had to, even if he was injured. He was, as one of the doctors on the tour said, ‘not fragile. He was a tough guy’. As he would prove, time and time again – not least this year when everything flowed so seemingly effortlessly.

Now it was time for the second round, Björn Borg against the American Marty Riessen. I remember the buzz that went through the crowd when Björn entered the court. Although he was not yet the emperor of the London grass, he had made a lot of noise in the previous year. Or rather, others had made a fuss around him. Especially the teenage girls. With his long hair and inward, inscrutable smile, he offered something new to the relatively paternal and square world of tennis when he made his debut as a 17-year-old in 1973. He was nicknamed the ‘Teen Angel’, and the ecstasy in which he sent hundreds of English schoolgirls into a frenzy was dubbed ’Borgasm’ by witty headline writers. ‘A Star is Bjorn’ was another headline. There were riots at all his matches, benches were overturned, flowerbeds trampled, police officers were called in and at one point one of them had his helmet removed. The girls screamed and the newspapers wrote.

This meant that the competition management soon realised that he drew large crowds to his matches, which therefore required a considerable amount of coverage, which meant that they could no longer put any of his matches out on the smaller side courts, as it would be total chaos. The fact that in 1973, the year of the boycott, he lost in the quarter-finals to British netminder Roger Taylor, that the following year he was knocked out by Egyptian Ismail El Shafei in the third round (and in straight sets too), and that in 1975 he lost to Arthur Ashe, also in the quarter-finals – it didn’t matter. The hype took on a life of its own, with schoolgirls clamouring for an autograph whether Björn won or lost. Now, in 1976, it was already a big deal whenever Björn played a match at Wimbledon. It is the buzz of this almost electric excitement that I hear when Björn Borg, wearing his pinstriped Fila underwear, and Marty Riessen enter the centre court.

That Björn would defeat Riessen was not in itself entirely sensational. He had done so before. At Wimbledon too, in 1975, though with reasonably close scores that time (3–1 in sets). But now it is something else entirely; Björn simply walks onto court and sweeps aside his opponent: 6–2, 6–2, 6–4. He gives away just six games in the entire match – one fewer than in the first round. Riessen tries stubbornly to attack; he has no other game, but Björn keeps finding the gaps, passes him, moves him about and wears him down. It is not even cat and mouse, for there is nothing playful here at all; it is quite simply an eerily efficient dismantling.

Marty Riessen: ‘I knew Björn because we played together for the Cleveland Nets in the World Team Tennis league. The six-player teams, three men and three women, were assigned to different cities across the United States, and the matches consisted of two singles, two doubles and one mixed doubles. The male players in Cleveland were Björn, myself and Bob Giltinan from Australia, and my abiding memory of Björn is that he wanted to train for four hours straight – and Bob and I had to split that time to keep up with him, two hours each, one right after the other with no break. It wasn’t a normal training regime, but then Björn wasn’t a normal player either.’ Riessen was one of the many great players – poor Vitas Gerulaitis was another – who never managed to beat Björn in a competitive match.

After the match an unruffled Björn gathers up his racquets and leaves the court. One must assume he gets back to the hotel as quickly as possible to submit himself to Bergelin’s famously rough massage, eat a steak with salad, and then spend the time until bedtime in his room behind drawn curtains. That is: unless he feels he needs to train for a session or two, since the match hardly made any notable demands on his strength. The road to success is built on routines, routines ... And who today can dispute this?

The third-round match too, against the Australian Colin Dibley – who had won a doubles tournament with Björn in Australia in 1974 – proved a relatively comfortable passage through the stifling heat: again 3–0. Björn hit 15 aces; the grind at The Cumberland paid off. Dibley bears witness to the same experience that David Lloyd had: ‘I was quite pleased to have him in the draw in 1976. I didn’t feel that he was, at this stage, good enough to beat me on grass. I served well. I felt I played quite all right, but I lost to him in straight sets. I don’t think I’d ever lost on grass to anyone who stayed back on the baseline before that match.’ Dibley goes on to say that most top players during this period were better on clay than on grass, and that there weren’t any players who were outstanding on both surfaces. And perhaps that was true, until Björn showed how to play deluxe clay-court tennis on grass.

In the fourth round waited the American Brian Gottfried, who during his highly accomplished career (a year later he was ranked third in the world) managed to defeat the Swede twice (against nine losses). There and then Gottfried didn’t have the shadow of a chance: 6–2, 6–2, 7–5. Björn served well, moved well, returned well; he did exactly what was needed. Yet he played this match injured. Bergelin had tried to get it postponed, without success. It was an overloaded stomach muscle that – after the endless grinding work on his serve – hurt so intensely that Björn couldn’t even turn over in bed without severe pain. How could he possibly play a fourth-round match at Wimbledon? Now good advice was not only costly (well, sort of), but also associated with certain risks. The evening before the match was filled with anxiety. Bergelin was anything but pleased with the idea of using pain-killing injections, but they managed to contact a doctor in town who assured them there were no serious risks of future damage. Which was why Björn decided they should take the chance. It was crunch time, pure and simple.

To Sune Sylvén, once the sports editor of Svenska Dagbladet, he said long afterwards: ‘I would hardly have done the same thing in a lesser context. But Wimbledon trumps everything, and I thought this could be my really big chance to win the greatest of them all. It could also have been the only chance. It might never come back. I would have tormented myself if I hadn’t tried. I just had to go for it.’

And go for it he did. Like clockwork. Despite serious injury. Björn just kept winning and winning, in straight sets to boot. Crushed all resistance, fought off every attack. Yet it was as if no one truly believed it could hold all the way. Sure, he had improved his serve, but his playing style was fundamentally the same, suited to the slow clay. Soon the fun would sadly be over, reckoned both the more or less self-appointed experts and other players alike. Might this possibly be the year of the mercurial Romanian genius Ilie Năstase? He had, after all, lost an extraordinarily close and thrilling final to the hard-hitting gentleman Stan Smith (who gave his name to those minimalist white Adidas shoes that periodically experience a renaissance among successive generations of young people who probably have rather hazy notions of who this Stan Smith actually was) in 1972, 7–5 in the fifth and deciding set. Năstase was now performing well on his half of the draw and appeared to have good chances of reaching the final. And in that case, no one believed that the young grafter from Sweden would pose any serious threat to the title that many felt the Romanian deserved – this despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that his antics and clowning often tested the patience of umpires and opponents very severely. Then, if not before, Björn Borg would meet his match on grass. And if not Năstase, there was always the hard-hitting American Jimmy Connors, who had won in 1974 and was hungry for revenge after losing the 1975 final to Arthur Ashe. This business with Björn Borg was amusing enough and interesting, but it would never last. Besides, he was injured, as everyone wrote and talked about. Bergelin wasn’t entirely happy and didn’t quite know where he stood: ‘I hate this business of playing on injections, but we have our chance now and we simply must take it.’

After the match against Gottfried came a quarter-final against his training partner and rival – at least initially – Guillermo Vilas from Argentina, the fellow he’d been hitting serves with at The Cumberland for two weeks, another baseliner who resembled Björn in many ways and who had also achieved his finest results on slower courts. Vilas was the player on tour Björn faced most often of all, in a full 23 tournament matches. He was also a player whom Björn learned to read over time, and whom he eventually simply stopped losing to. In the interview book My Life and Game Björn says that ‘Guillermo isn’t as quick as McEnroe, Gerulaitis, Connors or myself. But otherwise he and I play similar tennis, except that I do most things a little better than he does.’

Confidence, to be sure. But what can one say about it? Hardly misplaced. Björn’s record against him became as overwhelming as 18–5 in the end, and he beat Vilas in almost every important final. And precisely because they were so similar, and because Björn’s physicality and ball-striking were that bit sharper after all, Vilas was not someone he expected to lose to at this stage of the world’s most prestigious tennis tournament. He felt, moreover, that he held a psychological edge over the three-years-older Vilas, he said afterwards. His form was fantastic. And this match never became exciting either: 6–3, 6–0, 6–2. Such lopsided scorelines shouldn’t really be possible in a quarter-final. That the matches were so short also became something of a necessity because of the injury, since the three injections only worked for a few hours. To be certain of getting through the entire match without pain, Björn had to dispatch his opponent reasonably quickly. During the match against Vilas, Björn felt no pain at all. Afterwards, however: ‘I suffered for six days.’

So it was perfectly possible to play a match on injections, but the reckoning came, as Björn himself said, afterwards. After Wimbledon he allowed himself three weeks’ rest, and when he was due to resume training for a Davis Cup match for Sweden, the injury flared up again and he was forced to withdraw. He wasn’t fully recovered until two months later, just in time for the US Open. Tennis at the very highest level is also very much about fear and about an ability to shut out everything that disturbs concentration, everything that has been up until now and everything that is not the point that is to be played exactly right now. Most are afraid at some time – of suddenly not being able to perform at the peak of their ability, of the opponent getting into the zone and raising his game and never missing anything, of failing and making a fool of oneself in front of an audience – but then it’s a matter of getting over it immediately and absolutely not showing it. ‘If you’re afraid you lose. You simply must have courage and that has to do with self-confidence, of course,’ writes Björn (or speaks into Henning Sjöström’s tape recorder) in his book Till hundra procent