Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Aniara

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

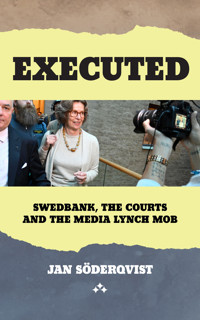

Executed? Isn't that an exaggeration? She's still breathing, isn't she? The term is borrowed from Per Lindeberg, who wrote the definitive book on the infamous dismemberment murder case. He speaks of a "social execution." Birgitte Bonnesen, former CEO of Swedbank, has been socially executed. She was fired, her contract with the bank was terminated by Göran Persson without any stated reason. She has been publicly shamed in the press for months and years. First acquitted, then convicted of gross fraud. In the dismemberment case, at least there was a crime to be innocent of. Here, there is nothing—except journalists who get everything wrong, legal authorities eagerly acting as the mob's enforcers, and a court that fails to understand the very evidence it relies on to convict. Yes, executed. This is a horror story. Jan Söderqvist is an author, writer, editor, and lecturer. Together with Alexander Bard, he has co-authored six books, including The Netocrats and the latest Process and Event, which have been translated into more than 20 languages. He is also the author of IceBorg, the unauthorized biography of Björn Borg, now being published in English.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 375

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Executed

Jan Söderqvist

Executed:Swedbank,theAuthorities and the Media Mob

© Jan Söderqvist

Cover design: Per Gustafsson

Cover photo: Fredrik Sandberg/TT

Aniara

www.aniara.one

All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher or author except as permitted by EU copyright law.

Contents

Quellich'usurpainterra il luogo mio,

il luogo mio, il luogo mio, che vaca

ne la presenza del Figliuol di Dio,

fatt'ha del cimitero mio cloaca

del sangue e de la puzza; onde 'l perverso

che cadde di qua sù, là giù si placa.

Dante. Paradiso Canto XXVII

Foreword

Asmostpeopleknow, the foreword of a book is the last thing the author writes. I placed the final full stop in this story, in late November 2024, in a villa on a Thai island. I had an extra drink or two that evening and felt immense relief. Just over two years of work had come to an end. I could now suddenly enjoy reading whatever I wanted. No more court documents or legal prose, for a while at least. And now, an editor would take over and carry my manuscript across the finish line. I had done my part.

However, the publishing company suddenly had a change of heart. The media was far too critical, particularly about Uppdrag Granskning, a television programme featured in my manuscript. The publisher claimed it was impossible to conduct a thorough fact-check because the Supreme Court had not yet decided whether to grant leave to appeal for Birgitte Bonnesen, so no qualified lawyers dared comment on my manuscript. Therefore, it couldn't be published.

Here's my take on this. As a publisher, you can publish whichever books you want. You can also reject manuscripts for any reason. You might think I'm a hack who can't write. That's perfectly fine. Even if you've signed a contract and paid an advance, an author can underperform, crash and burn halfway through. That’s entirely conceivable. But listening to this nonsense about fact-checking and the unnecessarily harsh criticism of Uppdrag Granskning from a publishing employee – who had no expertise – was disheartening. At that point, it seemed that something else was at play. All I could do was tip my hat and move on.

Uppdrag Granskning's role in this story will become clear, as will the reasons why the reportages in question and the subsequent, skilfully-orchestrated media frenzy deserve the strongest possible criticism. Recruiting one of the country's most qualified lawyers, who was also well-versed in the case, to fact-check my manuscript, took me exactly four minutes. The review was done over a couple of weeks – it can happen that quickly when one knows the material. Thankfully, other publishers and more modern alternatives are available for those with a story to tell.

Aniara is not a publishing house in the traditional sense, but it does produce books that have an audience. It translates and polishes manuscripts with AI-assisted affection and connects authors with their readers. So, my first big thank you - a foreword is, ultimately, written with the intention of thanking those who have provided support - is directed to Rickard Lundberg and all of the others at Aniara, who have ensured that this book reaches its audience - in several languages, no less. The process doesn't have to be as slow as the established book industry likes to suggest. Thank you.

Numerous individuals generously gave me their time – engaging in conversations, bouncing ideas around, answering questions and providing explanations – but the problem is they did so on the condition that they were not thanked, at least not by name. These include current and former Swedbank employees, and others with important knowledge and insights. The banking industry values discretion, as do many lawyers. In any case, I am deeply grateful to all who illuminated my path during this long journey.

The book does name some of of my sources and informants though. A big thank you to you as well!

Finally, I must thank Birgitte Bonnesen for gradually increasing her trust in me despite journalists betraying her countless times and intentionally misinterpreting and distorting her words. I thank her for understanding and always respecting the structure of the project and the fact that the book—and the final word—were mine. I listened to her objections and suggestions, but she understood she had no veto power.

This story is utterly horrific. It’s a tale of character assassination that risked evolving into a fully-realised miscarriage of justice. We are fortunate that it didn’t end in suicide like other, similar cases in recent history. But this is more than just a personal tragedy; it’s a dirge for a mediatised public sphere that’s dysfunctional on many levels. We continually see these senseless frenzies and media-driven legal proceedings, again and again. We never learn.

This situation is difficult to reconcile with our smug Swedish self-image, and it's becoming increasingly challenging to maintain the facade that our journalism is serious and that our authorities are credible. The central question isn't what drives journalists to gleefully form lynch mobs, destroying people's lives by repeating the most absurd and erroneous claims ad nauseam. No, the central question is what compels Swedish media consumers to consume Swedish media offerings against their better judgement. One might wonder why serious-minded journalists don't furiously protest against this senseless witch-hunting with no factual basis when it could reasonably lead to all credible investigative journalism being dragged through the mud. And how can any media institution be favoured with less trust than “Uppdrag Granskning”? How could that even be possible? Is it, at its core, about pure schadenfreude?

I am writing this at a time when the 40-year-old “Styckmordet” (“The Dismemberment Murder”) is, once again, back in the spotlight, thanks to a four-part documentary series for SVT created by Dan Josefsson and Johannes Hallbom, About two innocent doctors who had their lives shattered. Although they were ultimately acquitted of the actual murder of young Catrine Da Costa, it was claimed in court that it was beyond reasonable doubt that they had, together, carried out the dismemberment of her dead body. This argument was entirely based on statements from a 16-month-old girl, obligingly relayed via a woman who had persistently, but unsuccessfully, tried to have one of the doctors – her own ex-husband no less – convicted of incest.

How is this possible? Anyone who’s met a 16-month-old will know that the idea is bizarre. A young child will say anything and everything, if they say anything at all. It would be the same as if a two-year-old child was asked to recount memories from several months ago. They simply lack the linguistic and intellectual skills to form and reconstruct memories. The cassette tapes with the woman's persistent attempts to get the girl to talk about a dismembered corpse after the fact – tapes to which neither the court nor the press lent an ear – contained, of course, nothing to support the convictions of the woman, the prosecutor or the court, but both the court and the press were convinced beyond all reasonable doubt. Both men had their medical licence revoked by the national board of health and welfare and were sentenced to a lifelong shadow existence in a hostile environment due to journalists and judicial authorities believing that these two doctors were sadistic sex offenders. They were 'socially executed' to quote Per Lindberg, who, in his book Death is a Man, shed light on the Catrine da Costa case and dispelled the sectarian darkness (and who initially had trouble finding a publisher that could withstand the controversy).

Now, in hindsight, some journalists have expressed regret over their unresisting adherence to the lynch mob. Anna Hedenmo – formerly of SVT and chairperson of the Swedish Publicists' Association from 2017 to 2019 – was there when it all went down and wrote in Expressen (17 December 2024): 'I wish I could say that I wasn't swept up in the bloodthirsty media frenzy against the two doctors, that I asked critical questions of my superiors.' But she can't say that, because she didn't do it. There was no moral backbone, she just wanted nothing more than to belong and blend in. This may be a human response but rarely generates original or even useful journalism. She lit the pyre under the two doctors just like her colleagues. Being wrong in a large crowd costs, essentially, nothing. One can even manage to rake in a major journalism award or two before it becomes clear that one was wrong about everything. By the time that happens, everyone has long since turned the page and moved on. That is to say, of course, everyone except the socially executed.

The superiors Hedenmo mentions in her article had already decided the doctors were guilty. The doctors were obviously murderers of the worst kind. Such matters were — and are — a question of sensational drama rather than boring facts. Editorial decisions of this kind are made swiftly by Swedish media executives who raise a wet finger to the wind. According to one of my informants, it still largely functions this way. It's almost a given.

I watched the series “The Swedish Dismemberment Murder” and as time ticked on, I became increasingly dismayed, nearly numb, and lethargic. It's so disheartening. But then suddenly, at the end of the last episode, I pricked up my ears and sat up straight in my armchair. What? What did the narrator say? Did I hear that right? “Uppdrag Granskning”? You bet. Of course “Uppdrag Granskning” was involved here too, hounding harder than anyone else. In April 2007, they aired a report that stated the socially executed pathologist was not only guilty of murdering Catrine da Costa, but had also allegedly murdered his young wife, Anne-Catherine, several years earlier. Well, well! He wasn’t just a murderer but also a serial killer. Naturally, there wasn’t a shred of evidence, but that didn’t stop presenter Kattis Ahlström from saying: ’Yes, Anne-Catherine's mother was right after all. Anne-Catherine was likely murdered. And now we wait to see what conclusions the police and prosecutors draw from this today.’

Good heavens! So Mother was right after all! It just keeps happening, year in and year out. And as taxpaying media consumers, we apathetically allow this tomfoolery to continue. However, the price is paid by those whose careers and lives have been ruined by being accused of crimes they haven't committed. There were many innocent victims in the Swedbank case, in both Sweden and Estonia. Media-driven prosecutions were the icing on the cake. And Swedish courts, as will be shown,, don’t have the faintest idea how the media operates or conducts its business. And they pass judgement accordingly.

This is why anyone seeking mild and conciliatory media criticism should continue their search since this is not the book for them.

Stockholm, January 2025

Jan Söderqvist

Never mind

BirgitteBonnesenisnot at all typical of those occupying a position at the pinnacle of Sweden's business world. Two things set her apart from the crowd: one, she’s not a man, and two, she’s not Swedish. Neither of these factors are insignificant in the telling of this book’s story, nor to her career.

Her Danish accent persisted, even after 35 years in Sweden. She spoke quickly and energetically – sometimes a certain linguistic confusion arose between us, which forced me to remain focused and attentive. For example, at one point I think we discussed mortgages, which are an important source of income for all Swedish banks. I tried to keep up as best I could. Still, I couldn’t understand Birgitte's irritation about mortgages specifically, and eventually I had to interrupt and ask what were the grounds for her objection to them. Hadn't these contributed substantially to the positive results delivered by her own bank over the years? She looked at me, puzzled. We were discussing Per Bolund, the Miljöpartiet (Green Party) minister for financial markets and consumer affairs in the Löfven government, and I had to think back through our conversation and recall the last few exchanges in an entirely new context.

Birgitte Bonnesen arrived in Sweden on the 1st September 1987. Before that, she had made two brief visits to the country. The first was for a Bruce Springsteen concert at Ullevi in Gothenburg on the 8th June 1985, but neither Gothenburg nor Sweden left any impression on her then. The concert could have taken place anywhere. What she did remember well, apart from the concert itself (of which there is an audio-only recording on YouTube) was the bus ride home from Ullevi to Copenhagen during which she felt she was filled with music. She also remembered arriving in Copenhagen in the middle of the night and being let into a bakery via the back door to buy warm, freshly-baked rolls.