Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

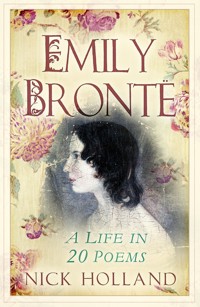

Emily Jane Brontë was born in July 1818; along with her sisters Charlotte and Anne, she is famed as a member of the greatest literary family of all time, and helped turn Haworth into a place of literary pilgrimage. Whilst Emily Brontë wrote only one novel, the mysterious and universally acclaimed Wuthering Heights, she is widely acknowledged as the best poet of the Brontë sisters – indeed as one of the greatest female poets of all time. Her poems offer insights to her relationships with her family, religion, nature, the world of work, and the shadowy and visionary powers that increasingly dominated her life. Taking twenty of her most revealing poems, Nick Holland creates a unifying impression of Emily Brontë, revealing how this terribly shy young woman could create such wild and powerful writing, and why she turned her back on the outside world for one that existed only in her own mind.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 384

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nick Holland is the author of In Search of Anne Brontë (The History Press, 2016), the acclaimed biography of the youngest Brontë sister, and he runs the website www.annebronte.org.

To my wonderful wife Yvette, you have made my life so beautiful, without you there are no words.

Front cover image: Emily Brontë (1818–48), English novelist, painting by Patrick Branwell Brontë c. 1833/PVDE/Bridgeman Images

First published 2018

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Nick Holland, 2018, 2025

The right of Nick Holland to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75098 842 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

1 Smiling Child

2 The Silent Dead

3 Bursting the Fetters and Breaking the Bars

4 Sweet, Trustful Child!

5 Friendship Like the Holly-Tree

6 The World Within

7 Sweet Love of Youth

8 A Tyrant Spell

9 Thy Magic Tone

10 I See Heaven’s Glories Shine

11 Come Back and Dwell with Me

12 Secret Pleasure, Secret Tears

13 Another Clime, Another Sky

14 We are Left Below

15 On a Strange Road

16 Vain, Frenzied Thoughts

17 Unregarding Eyes

18 The Slave of Falsehood, Pride, and Pain

19 Courage to Endure

20 A Further Shore

Appendix A: How Did Emily Brontë Get Her Name?

Appendix B: Emily Brontë’s Devoirs

Notes

Select Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I entered university in the autumn of 1989, and found that the first book on my reading list was Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. I was mesmerised from the opening page, and that weekend I made my first visit to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, where I purchased a framed picture of Emily, and Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte. My lifelong obsession with the Brontës had commenced, but little could I know where it would lead. I want to sincerely thank all the people who have made it possible for me to write my own biography of Emily Brontë, over a quarter of a century later.

Thanks go to my incredibly supportive family and friends, especially to Jenny Hall for a gift that proved immensely welcome and helpful. Thanks also to all at The History Press for their hard work and encouragement.

Thank you to the many individuals and places who have been of great assistance, including all the staff and volunteers at the Brontë Parsonage Museum, Stephen and Julie at Ponden Hall, the Fleece Inn at Haworth, Leeds University and the Brotherton Library, the British Library in London, John Hennessy, Cornwall Council, the Brussels Archives, the Hollybank Trust (once Roe Head School) and Sandra at the Brontë School House in Cowan Bridge (formerly the Clergy Daughters’ School, it is now a self-catering guest house and a much more agreeable place to stay than in Carus Wilson’s time).

I also want to thank all the people who have supported my website www.annebronte.org, a true labour of love, and those who have followed me so supportively on Facebook and Twitter, where you will find me named @Nick_Holland_. Finally, thanks go to you, the reader. I hope you enjoy my work and that it encourages you to return to the truly great work of the Brontës.

PREFACE

‘I have at this time before me the history of a mighty and passionate soul.’ So said Ellen Nussey when supplying Elizabeth Gaskell with information on one of the nineteenth century’s most enigmatic, and surely one of its most brilliant, writers. ‘It is of Emily Brontë I speak,’ concluded Ellen, and it is of Emily Brontë that I will be speaking throughout this book.

When I was writing Emily Brontë: A Life in 20 Poems in 2017 I was faced with a dilemma. Here was a writer of utmost genius, in my view (and I knew many others shared it) the author of the greatest novel ever set down on paper, and yet documentary evidence about Emily’s life was scant when compared to her sister Charlotte, or even her sister Anne.

Emily was an intensely shy woman who fiercely protected her privacy even when her writing was being placed before the world, and this creates challenges for those who would write a biography of this brilliant and unique writer. I believe, however, that Emily lived in both an external and internal world; her writing, especially her poetry, gives us a powerful insight into her thoughts and feelings, if we choose to see it.

Emily Brontë was a poet of the finest order. There can be little doubt that she was the greatest poet within the Brontë family, and one of the greatest poets of the nineteenth century as a whole – a time when the art form was reaching its zenith. In this book I have started each chapter with one of twenty poems by Emily, not only because they are fine verses worthy of study and admiration (although they are), but because I believe each is relevant to a particular period of her life.

While taking a broadly chronological approach, in that we will start with her birth in Thornton and end after her tragic yet courageous death in Haworth three decades later, we will use her poems to illustrate important themes and events in her life. From her days as a teacher, through her journey to Brussels, her passion for the moors, and the death of her siblings, Emily’s verse provides the perfect accompaniment and illumination.

It can be difficult at times to ascertain whether some of her verses are purely connected to Gondal, the imaginary world she created with Anne Brontë, or whether she is examining her own feelings and life within them. In many of her verses, the two sides of her creativity were inextricably intertwined. As Emily grew older, she retreated more and more into her imaginary world of Gondalian intrigue and adventure, until the lines between fiction and reality became blurred. Even her overtly Gondal-based poetry, then, can actually tell us about Emily herself.

Since writing Emily Brontë: A Life in 20 Poems in 2017 I have continued to research and write about Emily and her family. I have given talks and presentations on the Brontës across the United Kingdom, including addressing an audience in Penzance, the Brontë motherland, on the occasion of Emily’s 200th birthday. What has become clear is that Emily Brontë’s popularity continues to grow. There is a love for this shy, kind, genius of a woman which is almost without parallel in the world of classic literature, and the key to this can surely be found in her life, her novel and her poems.

I am delighted, therefore, to now set before the public this new paperback edition of Emily Brontë: A Life in 20 Poems, including new appendices which provide translations of her remarkable Belgian devoirs and a possible solution to the mystery of her name.

It may never be possible to say with certainty how Emily felt, or how she lived from day to day, but by looking at these wonderful verses we can gain fascinating glimpses of the woman behind some of the nineteenth century’s most enduring writing. Her novel and many of her poems contain incredible stories, but the life of the author herself is just as incredible, in its own way. Emily Brontë was, after all, no coward soul, but a visionary woman who refused to conform to anything other than her own ideas of what was right and what was wrong. In her life and works, Emily Brontë was a truly timeless woman and author, one who has the power to astonish us today just as much as she did the critics nearly 200 years ago, for there will always be novels, there will always be poetry, but there will never be another Emily Brontë.

1

SMILING CHILD

Tell me, tell me, smiling child,

What the past is like to thee?

An Autumn evening soft and mild,

With a wind that sighs mournfully.

Tell me, what is the present hour?

A green and flowery spray,

Where a young bird sits gathering its power,

To mount and fly away.

And what is the future, happy one?

A sea beneath a cloudless sun,

A mighty, glorious, dazzling sea,

Stretching into infinity.

(‘Past, Present, Future’, dated 14 November 1839)

EMILY BRONTË WAS 21 years old when she wrote her short poem ‘Past, Present, Future’. She was not yet the genius who would write Wuthering Heights, but her verse already showed many of the themes that would dominate her writing: a yearning for the past, the supremacy of nature, and visions of the future, visions of death and the eternity to follow.

Emily writes of the past as a smiling infant, but this is not any child – it is a remembrance of herself. When we think of Emily Brontë today we think of an insular yet powerful woman, one whose might with a pen belied her timidity in real life. It is easy to think of Emily as downcast, morose even, but while these terms may indeed be applicable to some of Emily’s life, they do not apply to the whole of her thirty-year existence. In her infancy, Emily was a smiling, happy child, a pretty girl doted upon by a loving family. It was an idyllic beginning full of promise, and one looked back upon fondly by Emily in the opening lines of her poem.

Thornton is a village around 4 miles from the city of Bradford, in what is now the county of West Yorkshire. It is surrounded to the south by moorland, and one property with a perfect view of the moors was Kipping House. The large and elegant house was home to the Firth family, heads of Thornton society and with the money to enjoy a life that most of the village’s inhabitants could only dream of.

The head of the household was John Firth, the village doctor. His first wife died in 1814 after a tragic accident that saw her thrown from a horse, but in 1815 he married his second wife, Anne. Also at the house was John’s daughter, Elizabeth, and she kept a diary detailing dinner parties, social gatherings, shopping trips, charitable work and more. It is in this diary, in an entry dated 30 July 1818, that the 21-year-old Elizabeth writes, ‘Mrs J. Horsfall called. Emily Jane Brontë was born.’1 This is the first record of Emily Brontë in print, but of course it was far from the last. Elizabeth Firth was to become an influential figure in the lives of the Brontës: a friend to Emily’s parents, a benefactor at times of need, godmother to Anne, and, as we shall see, a potential stepmother to the Brontë siblings.

Emily and her sisters, Charlotte and Anne, are to many the Queens of Yorkshire, and indeed they bring tourists from across the world, flocking to one particular western outpost of the county. They are also often thought of as being prim and proper examples of Victorian womanhood, but while this description may be applied to Charlotte Brontë, and to an extent Anne, although she was more willing to challenge the values of Victorian society within her writing, it could never be a description of the free-spirited and independent-minded Emily.

We need to go back a little further to get an idea of where Emily’s belligerence and rebelliousness come from. To discover Emily’s roots, and the beginnings of the Brontë family as a whole, we have to leave the churchyards of Yorkshire behind and look in upon an eighteenth-century elopement on the banks of the River Boyne. Emily’s father, Patrick Brontë, was a priest in the Church of England; it was a highly respectable position, if not necessarily a lucrative one, but of course he was neither born in England nor with the surname Brontë. The story is well known of how Patrick changed his surname to Brontë from the Irish Brunty, or perhaps Prunty, upon his arrival at St John’s College, Cambridge University, in 1802.2 The change in name was eventually adopted by his family in Ireland as well, including Emily’s grandfather, Hugh, who shared many characteristics in common with her.

Hugh Brunty’s story is unclear, even confusing, at many points, with associated legends that are now impossible to prove or disprove – obscured by the mists of time, and the sparsity of written records in eighteenth-century Ireland. Perhaps the most enduring myth, or possibly truth, about Hugh was that he was raised not by a Brunty at all, but by a cuckoo in the nest who had been brought from Liverpool – much like Heathcliff in Emily’s great novel. This account was brought to light by a late nineteenth-century treatise, The Brontës in Ireland by Dr William Wright. Wright based his book upon eyewitness accounts, and the stories of people who had known Patrick Brontë and his family, although it reads like an intoxicating mixture of fact and fiction, truths and half-remembered tales.

Patrick’s great-grandfather was a farmer and cattle dealer near Drogheda in County Louth, in what is now the Republic of Ireland, and he often travelled to Liverpool to sell cattle at the burgeoning market there. One of Wright’s sources recalled how the farmer came to adopt a helpless child:

On one of his return journeys from Liverpool a strange child was found in a bundle in the hold of the vessel. It was very young, very black, very dirty, and almost without clothing of any kind. No one on board knew whence it had come, and no one seemed to care what became of it. There was no doctor in the ship, and no woman except Mrs. Brontë, who had accompanied her husband to Liverpool. The child was thrown on the deck. Some one said, ‘Toss it overboard’; but no one would touch it, and its cries were distressing. From sheer pity Mrs. Brontë was obliged to succour the abandoned infant … When the little foundling was carried up out of the hold of the vessel, it was supposed to be a Welsh child on account of its colour. It might doubtless have laid claim to a more Oriental descent, but when it became a member of the Brontë family they called it ‘Welsh’.3

The author goes on to describe how Welsh Brunty, as he was known, elopes and marries his master’s daughter, Mary, in secret, and after being evicted wreaks revenge upon the family. Later he approaches one of his brothers-in-law and persuades him to let him adopt his son Hugh. Hugh is treated appallingly by Welsh, but eventually escapes and flees to the north of Ireland. This is supposedly the tale of the early years of Emily’s grandfather, Hugh Brunty, later Brontë, and the account has obvious similarities to Wuthering Heights – but is this because it was made up by either Wright or his source, or because it was a family folktale that Emily knew and drew upon?

We get a rather different account of Hugh from Patrick himself. Writing to Elizabeth Gaskell as she prepared to commence her biography of Charlotte Brontë, Patrick stated:

He [Patrick’s father, Hugh] was left an orphan at an early age. It was said that he was of ancient family … He came to the north of Ireland and made an early but suitable marriage. His pecuniary means were small – but renting a few acres of land, he and my mother by dint of application and industry managed to bring up a family of ten children in a respectable manner.4

One undisputed fact about Hugh was that he fell in love with Alice McClory from County Down. They wanted to marry, but there was a seemingly insurmountable obstacle in their way – Hugh was a Protestant and Alice was a Catholic. They eloped, and after a clandestine marriage in Magherally Church they set up home in a two-roomed cottage near Emdale in the parish of Drumballyroney. The cottage in County Down can still be visited today and has become a place of pilgrimage for Brontë fans, as it was here, just a year after the wedding of Hugh and Alice, that their first son was born. Born on St Patrick’s Day, 1777, he was named Patrick after the saint, and was to become patriarch of perhaps the most famous family in world literature.

Patrick, as he revealed in his letter to Mrs Gaskell, was the first of a large family and, recognising the financial burden upon his parents, he was determined to make his own way in life from an early age. They were, by necessity, a poor family, but hard working and one that was nourished with love. Patrick’s younger sister Alice commented on this at the age of 95 in 1891: ‘My father came originally from Drogheda. He was not very tall but purty stout; he was sandy-haired and my mother fair-haired. He was very fond to his children and worked to the last for them.’5

We also hear that Hugh Brunty was renowned as a wonderful storyteller, and it is likely to have been at Hugh’s knee that Patrick developed his own love of stories and of books. It was this love of literature that changed his life forever. Patrick was training as a weaver, but one day a passing minister, Reverend Andrew Harshaw, heard the young boy reading aloud from Milton’s Paradise Lost.6 So impressed was the priest that he offered to give Patrick free tuition at a school he ran.

Patrick proved himself such an able scholar that by the age of 16 he was master of his own school. His prodigious talents as a scholar and schoolmaster came to the attention of another Anglican priest, the Reverend Thomas Tighe of Drumballyroney.7 Tighe was a wealthy man, and hired Patrick to be tutor to his children. Once again, Patrick’s scholarly prowess, hard work and pious nature impressed those around him. Tighe recognised that this young Irishman from a humble background could have a career within the Church, if he received a little help along the way. Thanks to Tighe’s connections and money, Patrick Brontë was offered and accepted a scholarship at Cambridge University and a vocation to the priesthood. It was a stellar rise for a man who would otherwise have seen out his years working on a farm or as a weaver.

After graduating from Cambridge, Patrick was ordained as a deacon in 1806, and then as a priest in 1807. He served as an assistant curate in a number of parishes in the south of England, until in January 1809 he became assistant curate at All Saints’ Church in Wellington, Shropshire. He remained in the parish for less than a year, but it was in Shropshire that he made a very important friendship – that of local schoolmaster, John Fennell.

In December 1807, Patrick moved north to the parish of Dewsbury in Yorkshire. It was part of the ‘heavy woollen area’, a booming district that was being transformed by the Industrial Revolution and the mills and factories that it brought. By 1811, Patrick received his first curacy, at the village of Hartshead on the hills outside Dewsbury. This was a momentous occasion for Patrick, and within a year he also gained a position as an examiner in the classics at a local school.

John Fennell of Shropshire had moved to Yorkshire as well, and had founded a school at Rawdon, near Leeds. Discovering that his friend Patrick was nearby, and knowing his reputation as an excellent Latin and Greek scholar, he enlisted his help. Also at the school were John’s wife, Jane Fennell, their daughter, also called Jane, and their niece, Maria Branwell. She soon became the focal point of Patrick’s visits to the establishment.

Maria was from Penzance on the south-western tip of Cornwall, where she was born into a large and prosperous merchant family in 1783. However, by the time Patrick met Maria her fortunes had declined; her parents, Thomas and Anne, had both died and she was now looking to make her own way in the world by helping at her aunt’s school. Maria was in her late twenties, and Patrick in his mid-thirties,8 but they fell rapidly in love.

On 29 December 1812 they were married in Guiseley Parish Church near Leeds. At the same ceremony, Maria’s cousin, Jane Fennell, married Reverend William Morgan, a Welshman and close friend of Patrick. It was a joyous day, a double celebration, and Patrick and Maria may have had a premonition of William Morgan baptising their children in the years to come. This is a role he indeed fulfilled, but all too soon Morgan also had to preside over the funerals of many of them.

At the beginning of 1814 their first child was born, a daughter named Maria after her mother. A year later she was joined by a sister, Elizabeth Brontë. With a growing family, Patrick and Maria began to look for a new parish that offered a greater salary and more convenient living quarters, which is why, in May 1815, they moved to Thornton. In effect, the parishes of Thornton and Hartshead were involved in an ecclesiastical swap. Thornton’s curate wanted to be nearer to Huddersfield as he had fallen in love with Frances Walker, of Lascelles Hall near the town.

The arrangement was greatly to the benefit of Patrick and Maria, as Thornton came with its own grace and favour parsonage building on the town’s Market Street, whereas at Hartshead they had to rent a cottage on a farm. Thornton Parsonage is no longer owned by the Church of England, and although it may not be as famous as a certain parsonage building in Haworth, it is still well worth a visit. It is now an elegant café and delicatessen with an Italian theme, but it also contains items of interest to Brontë lovers, including its centrepiece – the early nineteenth-century fireplace by which the three writing sisters were born. Patrick may not recognise the building if he saw it today, but he would certainly recognise the name, as it has been named after his fifth child, and one who graced the building as an infant – ‘Emily’s’.

Patrick and Maria Brontë, like many newly married couples of the time, had children on an almost annual basis, but unlike the majority of their contemporaries all their children survived childbirth and infancy. The first child born in Thornton was named Charlotte, after one of Maria’s sisters, and a year later, in 1817, their first and only son was born and christened Patrick, after his father. Patrick would always be known by his middle name to his family, taking on the maiden name of his mother – Branwell. In the male-dominated world of the early nineteenth century it would have been expected that Branwell would one day become the family’s breadwinner, and that he would also support his sisters prior to their marriages, but it was a burden of expectation that he would find impossible to bear.

In the summer of 1818 the fifth child of Patrick and Maria was born; a child who was destined to write possibly the greatest novel of all time, as well as being one of the most remarkable poets of her day. From Elizabeth Firth’s diary, we know that the child’s name had already been decided on the day of her birth, but even in the choice of name, Emily differs from her other siblings, just as she was to prove to be different in many other ways as she grew into a strong-willed and independent woman.

Emily Jane Brontë was the only Brontë daughter to be given a middle name, with Jane presumably being chosen as a tribute to both Maria’s cousin and the aunt who had played a role in bringing her and her husband Patrick together. Both Janes, Fennell and Morgan, would act as godmothers to the girl. The choice of Emily has to remain a mystery, as there is no record of an Emily among either the Cornish or Irish relatives; this makes Emily the only Brontë not named after a parent, aunt or, in Anne’s case, after her grandmother. It seems fair to surmise that a woman named Emily must have been a friend known to Patrick and Maria, and a special one at that, whose name was given precedence over the Jane that would have been a more traditional choice in the family.

Emily Brontë started her life with a mystery, and she was to become a lover of mysteries, a creator of mysteries, and an enigma herself. Emily was a smiling and much-loved child, but as her poem reveals, even at an early age there was a mournful wind blowing through her life – a sighing breeze that would ever remind her of the early loss of her mother and two eldest sisters.

2

THE SILENT DEAD

I see around me tombstones grey,

Stretching their shadows far away.

Beneath the turf my footsteps tread,

Lie low and lone the silent dead –

Beneath the turf – beneath the mould –

Forever dark, forever cold –

And my eyes cannot hold the tears,

That memory hoards from vanished years,

For Time and Death and Mortal pain,

Give wounds that will not heal again –

Let me remember half the woe,

I’ve seen and heard and felt below,

And Heaven itself – so pure and blest,

Could never give my spirit rest –

Sweet land of light! thy children fair,

Know nought akin to our despair –

Nor have they felt, nor can they tell,

What tenants haunt each mortal cell,

What gloomy guests we hold within –

Torments and madness, tears and sin!

Well – may they live in ecstasy,

Their long eternity of joy;

At least we would not bring them down,

With us to weep, with us to groan,

No – Earth would wish no other sphere,

To taste her cup of sufferings drear;

She turns from Heaven with a careless eye,

And only mourns that we must die!

Ah mother, what shall comfort thee,

In all this boundless misery?

To cheer our eager eyes a while,

We see thee smile; how fondly smile!

But who reads not through that tender glow,

Thy deep, unutterable woe:

Indeed no dazzling land above,

Can cheat thee of thy children’s love.

We all, in life’s departing shine,

Our last dear longings blend with thine;

And struggle still and strive to trace,

With clouded gaze, thy darling face.

We would not leave our native home,

For any world beyond the Tomb.

No – rather on thy kindly breast,

Let us be laid in lasting rest;

Or waken but to share with thee,

A mutual immortality –

(‘I See Around Me Tombstones Grey’, dated 17 July 1841)

AS A YOUNG infant, Emily Brontë grew up surrounded by love, doted over by her oldest sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, and finding ready companions not much older than herself in Charlotte and Branwell. A happy life full of potential seemed to stretch before her, but as Emily’s poetry shows more than the writings of any of her sisters, a dark shadow was ever hanging over the fate of the Brontës.

It has to be said that many of Emily Brontë’s poems deal with dark, despairing themes. Death often forms the backdrop, as in ‘I See Around Me Tombstones Grey’, and, in some cases, becomes a character in its own right: brooding, waiting, inescapable. It is testimony to the childhood events that shaped Emily’s life more than any other, the early losses that would haunt her dreams and imagination until they found release in her verse and in her great novel.

By the start of 1820, Thornton Parsonage was becoming increasingly crowded for the Brontë family. As well as Emily, her three sisters and her brother, and Patrick and Maria Brontë, there were the family servants, Nancy and Sarah Garrs. Nancy Garrs arrived at the parsonage aged just 13 shortly after the birth of Charlotte, having been trained at the Bradford School of Industry for Girls: a charitable organisation which helped the children of poor parents. Her younger sister, Sarah, was also a graduate of this school, and she was recruited to join her sister at Thornton Parsonage shortly after Emily’s birth, with Nancy being promoted from nursemaid to cook and assistant housekeeper.

A contemporary account of the Bradford School for Industry reveals the very different background that the Garrs had compared to the Brontës, and also details the education they received:

The scholars, who are chosen by the subscribers, are taken in at eight years of age; and are taught to sew, knit, and read. They have materials to work upon found free, and the profits of their labours are expended in clothing them. The scholars also attend the school on the Sunday, and are taught to read and the Church Catechism, and attend church. Many excellent maid-servants have been reared in this school.1

Nancy and Sarah Garrs played an important role in Emily’s infancy and, although they later married and moved away, they retained links to the Brontë family and remembered the children fondly.

The year 1820 saw two pivotal events that changed the Brontë story forever. On 17 January, Emily’s beloved sister Anne was born. Anne Brontë was the sixth and final child of Patrick and Maria, and while she was ever to prove a blessing to Emily, her arrival made Thornton Parsonage even more crowded. In a letter sent to his friend Richard Burn just ten days after Anne’s birth, Patrick wrote, ‘There is, it’s true, besides this a very ill constructed Parsonage House, which is not only inconvenient, but requires, annually, no small sum to keep it in repair.’2

It would seem fortunate for all concerned, then, that Patrick and his family would soon be moving to a new parish with a much larger parsonage building: the parish of Haworth. Its long-standing curate, Reverend James Charnock, had died in early 1819, and the Vicar of Bradford, Reverend Henry Heap, wrote to Patrick to offer him the job, as Haworth was then a sub-parish of Bradford itself. Unfortunately, Heap had failed to consult Haworth’s Council of Elders, who had the traditional right of nominating their own parish priest, and they let it be known that they would not accept the imposition of Reverend Brontë upon them. Mindful of this impasse, Patrick politely declined the job offer,3 tempting though it was.

Heap’s next move was to give the post to Reverend Samuel Redhead, who had often stood in for Reverend Charnock during his final illness and seemed to be liked by the Haworth parishioners. This proved a great mistake. The story is told of how the parishioners turned violently against Reverend Redhead,4 at one point sending a drunken man into the church on the back of a donkey, and on another occasion chasing him out of the village in fear of his life.

It had by now become clear to Henry Heap that the villagers would not accept any curate foisted upon them, and that a compromise would have to be reached. In an act of diplomacy, it was agreed that the parish elders would nominate the original choice, Patrick Brontë, who would then be confirmed in the post by the Vicar of Bradford. In this way, pride and tradition were upheld, and the Brontës found themselves moving to their new parish in April 1820.

Two carts carried the family and their possessions on the undulating journey across the moors separating Thornton and Haworth. Emily was approaching her second birthday at the time, and we can imagine the bleak, majestic landscape capturing her eye. It was her first extended view of the moorland scenery that would become so well known to her – a moment of epiphany in her life. Unfortunately, Haworth was to bring another such moment just a year later.

The move to Haworth seemed to be a propitious one at first. The parsonage building was much larger, and Patrick’s salary increased too. Patrick was kept busy by the demands of this larger parish, it was true, but he was never a man to shun hard work. Maria also revelled in her new environment, raising her children with love and care at the same time as meeting the social demands that came with being the curate’s wife. Everything was bright in the Brontë household, but it was about to be shaken to its core.

The first winter at the Haworth Parsonage saw Emily and her siblings all catch scarlet fever. It was to be the first of many illnesses that they would suffer in the unhealthy atmosphere of the moor-side village, a place where epidemics swept away a significant number of the populace year upon year. The children all recovered on this occasion, but another family member was about to be struck down with something far worse, as Patrick recalled in a letter to Reverend John Buckworth, the man who had brought him to Yorkshire eleven years earlier:

I was in Haworth, a stranger in a strange land. It was under these circumstances, after every earthly prop was removed, that I was called on to bear the weight of the greatest load of sorrows that ever pressed upon me. One day, I remember it well; it was a gloomy day, a day of clouds and darkness, three of my little children were taken ill of scarlet fever; and, the day after, the remaining three were in the same condition. Just at that time death seemed to have laid his hand on my dear wife in a manner which threatened her speedy dissolution. She was cold and silent and seemed hardly to notice what was passing around her … A few weeks afterwards her sister, Miss Branwell, arrived, and afforded great comfort to my mind.5

On 29 January 1821 a sudden change had come upon Mrs Brontë. Whereas the day before she had carried out her maternal duties as usual, on this day she collapsed to the floor, overtaken by unbearable pain in her stomach. Doctors were called for, but Maria’s condition continued to worsen until it seemed obvious that things could end but one way. It was at this point that Maria’s sister, Elizabeth Branwell, left her Cornwall home and moved into the Haworth Parsonage. At first, she nursed her sister – later, she would nurse and raise the children. Elizabeth, who became known as Aunt Branwell to her nephew and nieces, had sacrificed all that she had known when she entered the Haworth Parsonage in the summer of 1821. She would never see Cornwall again.

Elizabeth Branwell was not the only newcomer to the parsonage at this time, as Patrick paid for a nurse to be brought in for his wife. This was one of his many desperate outlays at this time – expenses that would have left him destitute if it had not been for the kindness of friends, who later paid off his debts. One such gift, of the substantial sum of £50, was sent to him by ‘a benevolent individual, a wealthy lady, in the West Riding of Yorkshire’.6

The new nursemaid was not to Patrick’s liking and was eventually dismissed, and she is perhaps most known today as the previously anonymous individual responsible for the unfounded tales of Patrick in Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Brontë: tales of how he never fed his children meat and his explosive temper. It was the nursemaid’s revenge, and although she has long remained unnamed, recent research has revealed her to be Martha Wright (née Heaton). While her testimony regarding Patrick is less than reliable, she does provide a description of Emily at just 3 years old:

Maria [that is the daughter Maria, then aged 7] would shut herself up in the children’s study with a newspaper, and be able to tell one everything when she came out; debates in parliament, and I don’t know what all. She was as good as a mother to her sisters and brother. But there never were such good children … they were good little creatures. Emily was the prettiest.7

Patrick had spared no effort or expense in seeking help for the wife he loved, but it was all in vain. Maria Brontë died after a terrible prolonged illness on 15 September 1821, aged 38. It is commonly thought today that she died of uterine cancer, but this may not be the actual cause of her death. The known details surrounding her demise were examined in 1972 by Professor Philip Rhodes, a Brontë lover and one of the foremost experts in this medical field, being then the professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at St Thomas’ Medical School in London. Professor Rhodes concluded that Maria’s death was brought on by haemorrhage and infection after the birth of Anne a year earlier, or a chronic inversion of the uterus. He writes:

The ultimate cause of death in both instances would be cardiac failure due to the anaemia. Of course there is an outside possibility of cancer of some organ within the abdomen, but it is unusual for this to occur before the age of forty. Certainly genital cancer would be very unlikely when the previous normality of reproductive function was so well displayed.8

Aged just 3, Emily’s lack of years would have given her some defence against the grief caused by losing one’s mother as a child, but she would still have felt the loss as she grew older, even if she would find it hard to remember her face, or the Cornish lilt in her voice. Emily’s remembrance of this early loss can perhaps be seen in Wuthering Heights, with the first Cathy dying in childbirth and unable to see her daughter grow up.

Maria Brontë was the first of the Brontës to be buried under the cold flagstones of St Michael and All Angels Church – the same flagstones Emily would have to walk over every Sunday. While her mother did not have one of the grey tombstones referred to in her poem, she did not have to look far to see many such monuments as the window of her childhood bedroom, a room she shared with Charlotte as a girl, looked directly out onto the graveyard below. It was already a crowded graveyard by the time Emily and her family arrived in Haworth, and the epidemics that regularly struck the village saw it grow further still. Throughout her childhood, she would have become familiar not only with the sight of these monumental neighbours, the granite and stone edifices of death, but also with the sound of picks and shovels creating new graves.

Maria Brontë’s last words are reported as being, ‘Oh God – my poor children’,9 and it was perhaps this heartfelt exclamation which persuaded her sister Elizabeth that her place was now at the parsonage until the children were fully grown. One of the roles that Aunt Branwell took on was that of educator to the girls, teaching them scripture, as well as the needlework that would be expected to serve a dual purpose in their future lives. Money was often tight in the Brontë household, and Emily and her sisters would be expected to make their own clothing and mend existing clothing until it was finally beyond the point of repair; needlework was also an essential skill for a governess to teach her pupils, and both Patrick and Elizabeth must have assumed that this was the most likely career path for the sisters.

Patrick Brontë was a firm believer in the power of education – the transforming power that had taken him from Ireland to Haworth, via Cambridge University – but unlike many of his contemporaries, he believed that education could be of benefit to girls as well as boys. It was for this reason that Patrick wrote to his bank on 10 November 1824:

Dear Sir, I take this opportunity to give you notice that in the course of a fortnight it is my intention to draw about twenty pounds out of your savings bank. I am going to send another of my little girls to school, which at the first will cost me some little – but in the end I shall not lose.10

The little girl that he was sending to school on this occasion was Emily Brontë, but unfortunately for Patrick, Emily and the family, he had made a major miscalculation – one that would see him lose most grievously. The school he was sending Emily to join, and where three of her sisters already waited, was called the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge, but it has become infamous in literature as the deadly Lowood School attended by Jane Eyre.

Maria and Elizabeth Brontë had made the journey to Cowan Bridge on 1 July of the previous year, with Charlotte joining them there on 10 August. Maria and Elizabeth had previously enjoyed a term at Crofton Hall School near Wakefield, a prestigious establishment for girls that had once counted Elizabeth Firth among its pupils, but even though Elizabeth had made a contribution towards the school costs for Maria and Elizabeth, it was beyond Patrick’s means to keep them there or to send his three other daughters after them in their turn.

Cowan Bridge seemed an ideal compromise. Founded by the Reverend Carus Wilson in Westmorland, what we now know as Cumbria, it offered subsidies for the children of poor clergymen like Patrick. He would have expected that his children would be given a solid education in the skills they would need to be governesses and of course that they would be looked after while they were there, but Cowan Bridge was run on very different lines.

Carus Wilson was an arch-Calvinist; he believed in discipline and the importance of punishment, and considered that hardships on Earth were good for the soul. Charlotte Brontë, who would never forget the terrible scenes she witnessed at the school, would always insist that Lowood was an accurate portrayal of Cowan Bridge, that, if anything, it was even worse than she portrayed, with its lack of food, freezing conditions, arbitrary punishments and death ever lurking in its sick bays.

It is well known how Maria Brontë, the bright yet untidy girl with such promise, was treated especially harshly at the school, and how she is represented by the saintly Helen Burns in Jane Eyre, but, in contrast to this, Emily Brontë received very different treatment on her arrival at Cowan Bridge. Emily was the forty-fourth pupil at the school, and at just over 6 years old she was the youngest. In fact, the oldest pupils at the school were in their twenties, and only four were aged under 10 – three of those four being Elizabeth, Charlotte and Emily Brontë.

Nevertheless, Emily’s academic talents impressed her schoolmasters, who recorded her accomplishments upon entry as ‘reads very prettily and works a little’. The ‘work’ referred to is needlework, and this report on Emily is the most glowing given to any pupil in the Clergy Daughters’ School records.11 By contrast, Charlotte is described as ‘writes indifferently … Knows nothing of grammar, geography, history or accomplishments’. Maria’s description is, ‘Writes pretty well. Ciphers a little. Works badly.’

Emily, aged 6, obviously had winning ways, in contrast with the reserved woman she was to become, with her pretty looks and pleasing voice (later to be remarked upon by family friend John Greenwood) gaining approval from the often-harsh staff at the school. The school’s superintendent, Miss Evans, later recalled how Emily’s tender years and nature led to her being treated more favourably than others, calling her ‘A darling child, under five years of age, [who] was quite the pet nursling of the school’.12

Even so, there were two dread events to come that even Emily’s youth and pet status could not protect her from: she had to observe at first hand the demise and death of the two elder sisters she so looked up to. Charlotte Brontë described what happened in a mournful scene within Jane Eyre:

That forest-dell, where Lowood lay, was the cradle of fog and fog-bred pestilence; which, quickening with the quickening spring, crept into the Orphan Asylum, breathed typhus through its crowded schoolroom and dormitory, and, ere May arrived, transformed the seminary into a hospital … Many, already smitten, went home only to die: some died at school and were buried quietly and quickly; the nature of the malady forbidding delay.13

The Clergy Daughters’ School was indeed a place where death and disease were rife, with malnourished pupils falling prey to cholera, typhoid and consumption. Five girls were sent home from the school in ‘ill health’, as their records refer to it, on 14 February 1825. One of them was Maria Brontë – she would die in Haworth of tuberculosis on 6 May. By the end of May, Elizabeth had also been sent home, where she rapidly declined and died on 15 June.

Maria was buried under the church floor next to her mother of the same name, with Elizabeth alongside them. Patrick had seen enough, and quickly fetched Charlotte and Emily back to Haworth to be taught by him and their aunt in the safety of their own home.