Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

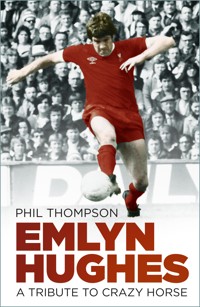

England and Liverpool captain Emlyn Hughes will be remembered as somebody who did everything to the maximum. Whether it was a swashbuckling footballer whose style earned him the nickname Crazy Horse, or as a television quiz show captain who rubbed shoulders with royalty, Emlyn Hughes never did things by half. He made his name at Liverpool, making 665 appearances between 1967 and 1979, helping the club to four league titles, an FA Cup victory and two UEFA Cup titles. He also helped establish the club as the top team in Europe, leading the side to its first European Cup in 1977. Phil Thompson looks back on the life of the legend who later carved out a career for himself in the media, where his face became known to non-football fans as the cheeky, long-serving captain on A Question of Sport.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 286

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to my grandchildren,

Ellie, Josh, Aaron and Sophie

Front cover image courtesy of PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo.

First published 2006 by Stadia

This edition published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Phil Thompson, 2006, 2023

The right of Phil Thompson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75095 981 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

A Tribute to Crazy Horse

Emlyn Hughes’ Golden Moments

The Key Managers

Season-by-Season Summary for Liverpool and England

Appendices

Bibliography

CHAPTER 1

‘If this boy was as good at football as he thinks he is, he would play for England’ – Emlyn Hughes’ school report, 1958

Emlyn Walter Hughes was born in the Cumbrian town of Barrow-in-Furness on 28 August 1947. Emlyn’s father, Fred ‘Ginger’ Hughes, had represented Great Britain at rugby league after moving to Barrow to join the local rugby league club. Fred came from Llanelli and had played for Wales Schoolboys as a youngster, and when an invitation came for him to play professional rugby league for Barrow for a signing-on fee of £500, he moved to Cumbria. His original plan was to take the £500 and then return to Llanelli as soon as possible. Fred told his brothers Harry, Dick and Emlyn (Emlyn Hughes was named after his uncle) that he had no qualms about signing for Barrow, but he would be returning home to the Welsh valleys before too long. The Hughes family consisted of seven children and Fred was often the only one bringing in a regular pay packet. No doubt a large chunk of the £500 found its way back to Llanelli, but Fred Hughes immediately took a liking to life in Barrow and decided to honour his contract and stay.

Playing as a prop forward for Barrow, he soon became a popular figure at their home ground, Craven Park. After a successful career at Barrow, he signed for Workington and played alongside the famous Gus Risman, at the time known as one of the hardest men in rugby league. Fred Hughes thought his rugby days had come to an end after retiring when Workington released him. An offer then came out of the blue for Fred to represent Wales against England in a rugby league international. He hadn’t played at all for two years, but, after a great deal of persuasion from Gus Lisman, he put his boots on again to represent his country against the old enemy.

When his rugby days finally came to an end, Fred was involved in a variety of occupations before setting up a tarmacking business with a friend. He even tried his hand at being an on-course bookmaker at the Westmorland course at Cartmel. Fred took the bets, Emlyn’s mother Anne, as clerk, did the paperwork and Fred’s brother Dick was the tic-tac man in the ring. Fred Hughes was never a licensed bookmaker, but the authorities never bothered him as he set up his pitch at Cartmel for a number of years. His pitch was known on the course as ‘Ginger’s Hill’. He was happy to make a profit of £20 and would not take a chance on laying big bets.

Cartmel races was a day out for the whole of the Hughes family and Emlyn Hughes’ own love of horse racing originated from his childhood days accompanying his family on their annual visit to the beautiful Westmorland course. In later years, Emlyn Hughes became a racehorse owner and even had a runner in the Grand National during the 1970s.

Fred Hughes’ tarmac business continued to put food on the table and he was happy to remain in Barrow with his wife Anne and their three boys, David, Emlyn and Gareth. David was four years older than Emlyn, with Gareth the youngest. Emlyn was born at 94 Blake Street in August 1947. Although the main source of employment in Barrow-in-Furness was shipbuilding, Fred Hughes was far too independent to have sought work at the local shipyard when his rugby days came to a close. Running his tarmac business suited him down to the ground. Most people in Barrow knew Fred Hughes as he walked through the town centre proudly wearing his British Lions blazer everywhere he went.

Although Fred Hughes was a confirmed rugby fanatic, he encouraged his children to be the best they possibly could in whatever was the sport of their choice. When Fred noticed that young Emlyn looked quite a prospect at football, that was it – from that moment on Fred attended every game, work commitments permitting, that he possibly could. Even if his son had a bad game Fred would be there after the match telling him that he was by far the best player on the pitch. If Emlyn Hughes did not succeed in becoming a professional footballer it would not be through a lack of confidence in his own ability – Fred ‘Ginger’ Hughes saw to that.

The family moved from Blake Street to a place just outside the town centre named Abbots Vale. Their new home was Vale Cottage, a bigger abode with a driveway where the growing Emlyn Hughes could hone his blossoming football skills. As soon as he got home from his local school, South Newbarns Juniors, it was England against Wales with his brothers and pals in the driveway. Young Emlyn was always on the England side, his ambition, even at an early age, being to play for the country of his birth and not his parents’ homeland of Wales.

Apart from his father, Emlyn Hughes stated in his autobiography that it was at South Newbarns Junior School that he came under the guidance of another influential figure in his young days as a footballer. Joe Humphreys was the headmaster of South Newbarns and took the under-11 football team. Emlyn’s school was the top team in Barrow for that age group during his days at the school. Some hard games took place against other local schools, but South Newbarns generally came out on top.

It was also during this period that Emlyn Hughes started to make regular visits to Holker Street to watch his idols Barrow Football Club take on the likes of Accrington Stanley and Workington Town in the old Third Division (North). Fred Hughes had always hoped that Emlyn might take a shine to rugby league as his sport of choice but, although Emlyn tried the oval ball game, he soon realised that it was football and not rugby where his talents lay.

The young Emlyn Hughes became so obsessed with Barrow FC that he even took to travelling to away games, as far afield as the likes of Exeter City, when the mood took him. If he didn’t have the money, he would hitchhike to away games with his younger brother Gareth. When the two dishevelled and hungry youths arrived back home they would inevitably receive a telling-off from their relieved parents before sports-mad Fred Hughes would then write a note excusing them for any absence from school.

Going on to secondary school, Emlyn continued to shine at sport at Risedale Secondary Modern. He played rugby league as well as football for the school and was selected to represent Barrow at rugby. The opposition were St Helens, who as always were full of talented young rugby league prospects. Barrow were thrashed 47-0, and this confirmed in young Emlyn’s mind, and that of his father Fred, that the round ball game was where his future might lie.

CHAPTER 2

‘They called me The Underseal Kid because that’s all I could do’ – Emlyn Hughes recalling his days as an apprentice motor mechanic

At Risedale Secondary Modern, Emlyn Hughes represented the school at cross country running as well as football and rugby. At the age of thirteen, however, his spurt of growth came to a temporary end. The other lads in the school caught up with him and in many cases overtook him when it came to size and physique. From being the outstanding young sportsman for his age group, his peers now overtook him as they grew stronger.

His interest in playing football received a temporary setback, but his allegiance to his heroes in the blue and white of Barrow Football Club remained as strong as ever. He even approached the club secretary at Holker Street one day to request a trial for Barrow. The club allowed him to train with the amateurs and youth team players of an evening when he reached the age of fifteen. At this period in his teenage years, however, Emlyn Hughes was not the young strapping hulk of a teenager who would impress Bill Shankly when the legendary manager witnessed his Blackpool debut four years later. Barrow failed to take him on, mainly on the grounds that he wasn’t big enough for the tough, hard world of Fourth Division football.

At this stage Fred Hughes’ tarmac business was beginning to develop and Emlyn was packed off to learn a trade. Fred’s choice was that he should be a motor mechanic and his dejected young son began work as an apprentice at a firm situated in Barrow, aptly named Emlyn Street.

Emlyn Hughes hated his days working in the garage, his dream still being to become a professional footballer. However, he reasoned that if he hadn’t shown enough promise for Barrow to take him on, then he had very little chance of impressing a bigger club.

Emlyn continued to play local junior football in the Barrow and District League. The club he signed for was Roose Juniors. There he came under the guidance of Bill Evans, who instilled in Hughes a new determination to make it in football, but it was through the sheer determination of Fred Hughes that the crucial breakthrough came.

Emlyn continued to play for Roose on Saturday and Sunday afternoons, while Fred Hughes worked behind the scenes to get his son a trial at a professional club. If anyone wants to know from whence Emlyn Hughes got the incredible drive and determination that was such a feature of his fantastic football career, they need look no further than his father Fred Hughes. Although Fred would have loved to have seen Emlyn become a top rugby league player, like his eldest son David did at Barrow, he never gave up helping his football-obsessed offspring to fulfil his dream.

Emlyn continued to set off every morning to the garage in Emlyn Street to learn the ins and outs of becoming a motor mechanic. In later years he confessed that the only job he was any good at when it came to car repairs was undersealing them. ‘They called me The Underseal Kid,’ he once exclaimed, ‘because that was all I could do.’

Emlyn Hughes’ parents were no different from any others during the 1960s in wanting their children to learn a trade as the passport to happiness and a means of earning a living. Like a great number of teenagers forced into embarking on five-year apprenticeships that would ‘set them up’ in later life, Emlyn Hughes resented every minute of it.

He played his heart out every weekend for Roose Juniors, hoping that a scout from one of the Lancashire clubs might be standing on the touchline and be suitably impressed with his all-action style of play. At this stage in his career, Emlyn was still playing as an inside forward, and scored his fair share of goals. He once set a record for goalscoring during his days playing for South Newbarns under-11s and he always thought his future in the game would be as a forward.

The big break for Emlyn Hughes came when his father decided to approach Ron Suart, the Blackpool manager, in the hope of attaining a trial for his son at Bloomfield Road. Emlyn knew that Suart was a native of Barrow and Fred Hughes had known the likeable Suart for many years. Suart had been a top defender for Blackpool and Blackburn Rovers during his playing days and after winning promotion to the Second Division for Scunthorpe in 1958, it was clear he was an up-and-coming young manager.

Blackpool offered Ron Suart the opportunity to become a First Division manager at the beginning of the 1958/59 season and he took over the reins at Bloomfield Road. Suart was known as an honest manager and was very quietly spoken. He had developed a reputation for bringing young talent to fruition at Blackpool and one only has to look at the careers of two future England greats, Alan Ball and Emlyn Hughes, to realise that his ability to spot young talent was second to none.

After months of badgering by his persistent son, Fred Hughes took the opportunity, while carrying out some tarmac work in Blackpool one day, to make his way to Ron Suart’s office and attempt to get Emlyn a trial at the club. With Suart being a Barrow-born man, surely, he thought, he would give a talented kid from his own place of birth just one chance to show his worth.

Fred’s determination paid off and he was invited to bring his son to Bloomfield Road the following week. Emlyn Hughes was ecstatic. He always had confidence in his own ability and now he had a chance to prove himself at a First Division club. The problem was, however, that Emlyn Hughes had still not undergone that spurt of growth that made him look such a powerful player in later years. He was still relatively small for his age and although Blackpool’s assistant manager Eric Hayward and youth team coach Bobby Finnan thought Emlyn Hughes had ability, his size went against him. After running the rule over Emlyn in a few trial games, they told Fred to bring his son back in a few months. Fred and Anne Hughes then set about building up their growing teenage son with a diet of steaks and whatever else they could feed him up on.

Emlyn Hughes started to play the occasional game for Blackpool’s ‘B’ team and assistant manager Eric Hayward began to take a keen interest in the youngster’s performances. Hayward had been a centre half in the famous Blackpool glory days of the mid-1950s when the seasiders had won the FA Cup in a fabulous 1953 final against Bolton. He knew the game inside out and began to give the young Emlyn Hughes a rollicking on a regular basis. Hughes was at first disconcerted to be on the receiving end of Hayward’s tongue lashings, but then reasoned that if he didn’t have anything to offer then the old pro wouldn’t have bothered with him. Hayward cajoled Hughes with a mixture of bullying and praise into becoming a better player. Added to the fact that he was now beginning to grow much bigger and stronger, Emlyn Hughes was now starting to look a prospect. If Ron Suart or Eric Hayward turned up to take a look at training sessions or junior team matches that Hughes was involved in, the youngster from Barrow pulled out all the stops in an effort to impress them.

As at every stage of his son’s development, Fred Hughes now decided to make the next move in Emlyn Hughes’ career. He moved Emlyn out of the family home and set him up in digs in Blackpool. He wanted him nearer to the training ground at Squires Gate and he also contacted a garage to enable him to continue his apprenticeship as a motor mechanic. Although he was reluctant to leave the warmth of the family home in Barrow, Emlyn Hughes knew he had to give football his total commitment if he was ever to fulfil his dream of becoming a professional. Emlyn Hughes lodged at 2 Levens Grove, Blackpool with Johnny Green, Hughie Fisher and Alan Ball. Green and Fisher would eventually become top-class First Division players; Hughes and Ball were destined to become football legends. At some stage in the future a blue plaque should be erected at 2 Levens Grove stating that it was once the residence of two future England captains.

Emlyn Hughes settled in well at his new lodgings and was well looked after by his landlady Mrs Mawson. He would work in the day at Blackpool’s Imperial Garage and then make his way to Squires Gate for training sessions in the evening. He envied his fellow lodgers at Levens Grove who would still be in bed when he was setting off for work on a cold winter’s morning. Emlyn would have to do a full day’s work and grab a quick bite to eat during the day before setting off for training at 5.00 p.m. The full-time apprentices were allowed to concentrate fully on their football careers at Blackpool. Hughes would arrive back at his digs to eat his evening meal often after nine at night. It was all worth it to Emlyn, however; he had always wanted to be a part of a top First Division club and he was now well on the way to achieving his dream.

Now playing in midfield, Emlyn Hughes eventually forced his way into the Blackpool youth team. He really made his mark when he knocked a goal in past Blackpool’s star goalkeeper, Tony Waiters, in a pre-season trial match playing for The Whites against The Tangerines. These public trial games were a feature of most teams’ pre-season activities at the time and would allow the supporters a taste of what would be on offer in the coming season.

Blackpool manager Ron Suart, the man who gave Emlyn Hughes his first break in professional football. Suart told Emlyn after his debut against Blackburn, during which he attempted to kick everyone in a blue and white shirt, ‘You certainly made an impact out there son.’

Hughes was now beginning to make his mark at Blackpool and had even received a mention in the local press. Fred Hughes told Emlyn that Ron Suart had assured him that the teenager was soon to be offered professional terms at the club. He had been training at Blackpool for a year and a half and the day arrived when he was called into Suart’s office to hear whether or not he was to be offered a contract. When Suart told him the magic words – that he was to become a full-time professional – Hughes could not contain his joy. He felt as though he was walking on air as he quickly signed the form put before him and left Suart’s office. The fact that he would now be receiving the princely sum of £8 a week didn’t concern him in the slightest. He could now train full time and his dreaded days as an apprentice motor mechanic were destined to become a rapidly fading memory.

CHAPTER 3

‘At Blackpool I remember Emlyn Hughes telling me that I’d always be a banker, or something that sounded very similar’ – Graham Kelly, former chief executive at the FA and a teammate of Emlyn Hughes as a youngster at Blackpool

Blackpool FC, the club Emlyn Hughes became a full-time professional with in 1964, was a club in decline. The only trophies they had ever won were the Second Division Championship in 1930 and the FA Cup in 1953. They had finished runners-up to Manchester United in the First Division in 1956, but had been 11 points behind the brilliant ‘Busby Babes’.

Despite the fact that they were now struggling to maintain their First Division status, there was still something special about the seaside club. Perhaps it was the almost exotic tangerine shirts that they played in, or the memories of the great Stanley Matthews leading a sensational Blackpool fightback against Bolton Wanderers in the FA Cup final of 1953.

Despite their lack of success when it came to silverware, Blackpool had always produced outstanding players throughout their history. From Jimmy Hampson in the 1930s and the great Stan Mortenson in the post-war period through to Jimmy Armfield, Gordon West and Alan Ball in later years. The production line of top professionals kept rolling on.

Although they regularly had gates of 30,000-plus in the 1940s and ’50s, by the 1960s attendances had fallen and, to survive, Blackpool had to sell their best players when suitable offers came along. Apart from the outstanding England full-back Jimmy Armfield, who made 568 appearances for the club, most of their top players moved on when a bigger club came in for them.

Emlyn Hughes admitted that his first year as a full-time professional at Blackpool did not go as well as he expected. Training with the likes of Armfield, Ball, Waiters, Green and all the other first-team players helped to bring him on, but he still thought a breakthrough into the First XI was years away. He turned out for the ‘A’ and ‘B’ teams on a regular basis, but his aim was to make an appearance for the Central League side. The Central League was the last step before the first team and Emlyn Hughes was in a hurry to make the next step up in his career.

Although Alan Ball shared the same lodgings as Emlyn Hughes, he was spending less and less time at Levens Grove. His parents lived in Farnworth, which was a short distance from Blackpool. Ball would spend only a couple of evenings a week at his lodging house, but Emlyn Hughes was taken for a drive around Blackpool by the future England World Cup hero on the odd occasion. Alan Ball had a red Ford Zephyr and the youngsters at Mrs Mawson’s found it a great thrill to be seen parading around Blackpool town centre with the local football club’s up-and-coming star.

Emlyn Hughes might have looked up to Ball as a player, but that didn’t stop him once getting stuck into him with a piledriver of a tackle that would become his trademark in later years. During a practice session at Squires Gate, Hughes left Blackpool’s prized asset writhing on the ground in agony after hitting Ball just above the ankle in a full-blooded attempt to take possession of the ball. The Blackpool training staff gave Hughes a rollicking as they attended to the stricken Ball.

When the game restarted Alan Ball noticed that Emlyn Hughes was now holding back when it came to tackling for the ball. Ball took the young midfielder to one side and gave him another rollicking, telling him that he must never hold back, even if he was playing against the most famous player in the world.

Emlyn Hughes heeded Alan Ball’s words and his fearsome tackling was to be one of the main reasons for Liverpool boss Bill Shankly being attracted to him. Alan Ball encouraged Hughes to be no respecter of reputations when it came to the field of play. Alan Ball himself didn’t think twice about voicing his feelings and he once even gave the legendary Stanley Matthews a rollicking when he refused to run after a Ball pass because the Blackpool youngster had not played the ball into the maestro’s feet where he preferred it.

Fred Hughes continued to keep a close eye on his son’s football education at Blackpool and would quiz Emlyn constantly to make sure he was looking after himself. When he travelled back to Barrow after a game on the Saturday, Emlyn Hughes would have to tell his father what he had been up to that week. He was constantly warned not to smoke and drink and to avoid late nights at all costs. Emlyn would still help out in the summer months with the tarmac business, hoping that the coming season would be the one in which he would make a first-team breakthrough.

Another young player at Blackpool at the time was future chief executive of the Football Association Graham Kelly. Kelly’s daytime occupation was as an employee of Barclays Bank, and he played several games for the Blackpool ‘A’ team as a goalkeeper during the mid-1960s. Graham Kelly recalled Emlyn Hughes approaching him after one poor goalkeeping performance and telling him that he was wasting his time at Blackpool: ‘I remember Emlyn telling me I’d always be a banker, or something that sounded very similar, after one heavy defeat,’ Kelly remarked in his autobiography. ‘He, of course, went on to play for England; I did not.’ Hughes was clearly never afraid to voice his opinions, even during his early teenage years at Blackpool.

Emlyn Hughes’ path to the Blackpool first team came about by chance. He turned up for a Blackpool ‘A’ team game and was told that the regular left-back was unable to play. Hughes played at full-back for the first time in his life and looked impressive. Emlyn had only been expected to be a reserve for the game, but a twist of fate had thrown him in at the deep end and he had performed well.

He was then selected at left-back for the next six games and looked like he had been playing there all his life. Eric Hayward told Hughes that at long last he looked like he had found his true position. The Blackpool reserve-team left-back John Prentis then found himself out of the game for a long period with a broken leg and in April 1965 Emlyn Hughes made his Central League debut against Blackburn Rovers. They drew 1-1 and a few days later Hughes was selected again for the reserves against Burnley. Once again the game ended in a 1-1 draw.

Emlyn Hughes played throughout the 1965/66 season as an established Central League player, but he was now desperate for a first-team chance. Fred Hughes decided that Emlyn’s chances of making the first team needed a helping hand and he took to writing to the Blackpool Saturday-night football newspaper letters page using different noms de plume. He would make comments such as, ‘When is this young lad Emlyn Hughes going to be given a first team chance?’ and ‘Emlyn Hughes looks one hell of a prospect. Surely he deserves a chance in the Blackpool team’ – all of which had Blackpool supporters asking just who was this exciting young player in their reserve side? Fred Hughes also took to standing near the directors’ box shouting, ‘Hells bells, this lad at full-back looks useful. He’s getting better every game!’

Whether Fred Hughes’ one-man campaign to get his son a chance in the first team worked one will never know, but at the end of the 1965/66 season Emlyn Hughes’ dream came true. With Blackpool’s England players Jimmy Armfield and Alan Ball called up for early training ahead of England’s 1966 World Cup campaign, Emlyn Hughes was selected for an end-of-season game at Blackburn Rovers. Regular Blackpool left-back Tommy Thompson was switched to the right to take Armfield’s place and Emlyn Hughes came in on the left. The date was 2 May 1966.

Among the spectators at Ewood Park that night was the boss of Liverpool Football Club. His team had just won the First Division title at a canter but, as always, he was relentless in his pursuit of new talent to make his outstanding Liverpool side even more formidable. Recalling the game in his autobiography, Bill Shankly said he couldn’t believe his eyes when the action started. Shankly recalled: ‘I said to Ronnie Suart, the Blackpool manager, “Who’s playing?” and he said, “There is a boy here from Barrow in his first game.” He didn’t half play! He did everything – even to the extent of getting a player sent off. The player retaliated against Emlyn, who was in the right, and I thought that will upset him, but it didn’t. He kept on playing and was cutting inside, and cutting the ball back out. I offered £25,000 for him right after the match. I said to myself, “This is somebody special.”’

Shankly also revealed that he had also been alerted to Emlyn Hughes’ potential by a mystery letter writer from The Fylde. Whether this was Fred Hughes up to his old tricks is something we will never know, but Emlyn Hughes’ name on the team sheet against Blackburn on that May evening in 1966 was definitely not the first time that the kid from Barrow had been brought to the great man’s attention.

Emlyn Hughes thoroughly enjoyed himself on his debut. Fred Hughes had always instilled in him the importance of making his mark early on in a game. When the young full-back kicked the Blackburn hero Bryan Douglas in the first few minutes of play and sent the England winger sprawling over the touchline, he certainly had the crowd up in arms. Emlyn Hughes was waging a one man war against Blackburn and he was enjoying every minute of the experience. Bryan Douglas was an outstanding winger and could easily have given the inexperienced Hughes the runaround. The Blackpool debutant decided to try and nullify Douglas early on and by all accounts achieved his objective.

It is highly likely that Bill Shankly had had one of his backroom staff at Anfield dispatched to Bloomfield Road to check out the young Blackpool full-back in one of his reserve-team appearances. When he found out that Emlyn Hughes was due to make his debut against one of England’s finest wingers, it was an opportunity that was too good to miss. No doubt Shankly was tipped off by the mystery letter writer from the Fylde that the subject of his glowing references was due to make his first-team bow.

Also in the crowd that night at Ewood Park was Manchester United boss Sir Matt Busby. It is not recorded whether United’s legendary manager was also impressed by Emlyn Hughes’ sensational debut, but the following morning’s sports pages gave the Blackpool debutant several mentions.

Fred Hughes had advised his son to make a mark for himself as quickly as possible. Apart from laying out Bryan Douglas in the first few minutes, Hughes also became involved in a flare-up with George Jones which resulted in Jones being sent off. He then argued his corner with seasoned Blackburn professionals such as Mike Ferguson and Barry Hole, who were desperately attempting to wind the Blackpool teenager up in an attempt to get him sent off. Hughes just laughed as the Blackburn supporters booed and jeered every time he touched the ball.

When Blackpool went in 2-0 at half-time, a smiling Ron Suart congratulated Hughes, telling him that he was certainly making a name for himself. Blackpool won the game at a canter and were safe from the threat of relegation for another season. Blackburn Rovers were already relegated, but to be trounced by their Lancashire rivals was the final straw in a dreadful season at Ewood Park.

Although Bill Shankly wanted to take Emlyn Hughes back to Anfield there and then, Blackpool were not in any desperate need for an injection of cash, mainly because their star man Alan Ball was certain to be moving from Bloomfield Road after that summer’s World Cup finals had come to an end. After Ball’s fantastic displays for England in the 1966 tournament, Blackpool sold him to Everton for the then British record transfer fee of £110,000. For the time being the finances at Bloomfield Road were in a healthy state. Bill Shankly would have loved to have taken Alan Ball to Anfield, but after missing out on one major Blackpool talent, he was determined that he was not going to miss out on the Lancashire club’s other young gem. He was determined that Emlyn Hughes would be a Liverpool player before too long.

CHAPTER 4

‘I knew he was a winner. There are some players you go to watch and you really think they can play, but you are not too sure. I knew with Emlyn Hughes there was no risk’ – Bill Shankly

At the start of the 1966/67 season English football was on a terrific high. Alf Ramsey’s ‘wingless wonders’ had just become World Champions after a glorious summer of football. On Merseyside, Liverpool were League Champions and Everton FA Cup winners. Even at Bloomfield Road, Blackpool were optimistic that the sale of England hero Alan Ball to Everton for £110,000 would allow Ron Suart to delve into the transfer market and build a team capable of relinquishing their tag as one that always seemed to be fighting against relegation.

To Jimmy Armfield and his Blackpool teammates however, the sale of Alan Ball was a kick in the teeth. After impressing against Blackburn at the end of the previous campaign and then looking outstanding in pre-season friendlies, Emlyn Hughes thought he might have been in the side for the start of the new season, but Hughes was not selected for the opening game away to Sheffield Wednesday. As it happened Blackpool lost 3-0 and looked a dejected bunch of players as they trudged back to their dressing room after the match. Jimmy Armfield revealed in his autobiography that it was one of the few occasions when he lost his rag with affable Blackpool boss Ron Suart. Armfield recalled: ‘Nothing summed up the state of Blackpool FC better than Ball’s departure to Everton in the summer of 1966. They allowed him to leave just weeks after he had played a leading role in England’s World Cup victory. He was a national hero and a cult figure in Blackpool, but the club regarded him as expendable and he was sold just before the start of the new season. We had lost our World Cup star and were beaten 3-0.’

A star in the making. Emlyn Hughes pictured just after he broke into the Blackpool first team in 1966. Within months of this photograph being taken Bill Shankly had whisked the talented teenager off to Anfield.

Armfield had words with Suart after the game: ‘“I don’t know what was up with you lot out there today,” said Ronnie as we sat in the dressing room. “You don’t know what was up with us?” I asked. “You go and sell our World Cup winner and then you wonder what’s wrong. What do you expect?”’

Emlyn Hughes’ next first-team chance came the following week when he came on as a substitute for Johnny Green in Blackpool’s game against Southampton. Hughes then kept his place for a midweek game against Leicester City. He played well in a 3-2 defeat and Ron Suart congratulated him on his display after the game.

After that fixture, Emlyn Hughes retained his place in the Blackpool starting line-up until his transfer to Liverpool. ‘That game against Southampton was the turning point of my career,’ he remarked. ‘I held my place ever since.’