18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

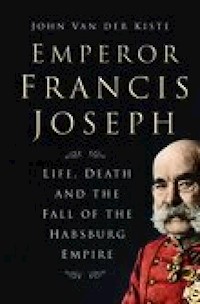

In 1848, 28-year-old Francis Joseph became King of Hungary and Emperor of Austria. He would reign for almost 68 years, the longest of any modern European monarch. Focusing on the life of Emperor Francis Joseph and his family, this book examines their personal relationships against the turbulent background of the 19th century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Ähnliche

EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH

ALSO BY JOHN VAN DER KISTE

Published by Sutton Publishing unless stated otherwise

Frederick III, German Emperor 1888 (1981)

Queen Victoria’s family: a select bibliography (Clover, 1982)

Dearest Affie: Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria’s second son, 1844–1900 [with Bee Jordaan] (1984)

Queen Victoria’s children (1986; large print ISIS, 1987)

Windsor and Habsburg: the British and Austrian reigning houses 1848–1922 (1987)

Edward VII’s children (1989)

Princess Victoria Melita, Grand Duchess Cyril of Russia, 1876–1936 (1991)

George V’s children (1991)

George III’s children (1992)

Crowns in a changing world: the British and European monarchies 1901–36 (1993)

Kings of the Hellenes: The Greek Kings 1863–1974 (1994)

Childhood at court 1819–1914 (1995)

Northern crowns: The Kings of modern Scandinavia (1996)

King George II and Queen Caroline (1997)

The Romanovs 1818–1959: Alexander II of Russia and his family (1998)

Kaiser Wilhelm II: Germany’s last Emperor (1999)

The Georgian Princesses (2000)

Gilbert & Sullivan’s Christmas (2000)

Dearest Vicky, Darling Fritz: Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter and the German Emperor (2001)

Royal visits in Devon and Cornwall (Halsgrove, 2002)

Once a Grand Duchess: Xenia, sister of Nicholas II [with Coryne Hall] (2002)

William and Mary (2003)

EMPEROR FRANCIS JOSEPH

LIFE, DEATH AND THE FALL OF THE HABSBURG EMPIRE

JOHN VAN DER KISTE

First published in the United Kingdom in 2005 by Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© John Van der Kiste, 2005, 2013

The right of John Van der Kiste to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9547 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

List of Plates

Preface

Acknowledgements

Genealogical Table

One

Sovereign in Waiting

Two

‘Physically and Morally he is Fearless’

Three

‘A Firmness of Purpose’

Four

‘Going Down with Honour’

Five

‘Incredibly Devoted to his Duties’

Six

‘He Stands Alone on his Promontory’

Seven

‘One Cannot Possibly Think of Anything Else’

Eight

‘Nothing at All is to Be Spared Me’

Nine

‘A Crown of Thorns’

Ten

‘The Machinations of a Hostile Power’

Eleven

‘Why Must it Be Just Now?’

Notes

Bibliography

List of Plates

Archduchess Sophie and Archduke Francis Joseph as a child

Emperor Francis Joseph, 1848

Emperor Francis I, Archduchess Sophie and Francis Joseph as a boy

Archduchess Sophie and Archduke Francis Charles

Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico

Empress Elizabeth

Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna

The Kaiservilla, Bad Ischl

Emperor Francis Joseph in the robes of the Order of the Golden Fleece

Crown Prince Rudolf

Crown Princess Stephanie

Katherine Schratt

Empress Elizabeth

Emperor Francis Joseph and his grandchildren

Archduke Francis Ferdinand, Sophie and their children

Emperor Francis Joseph and King Edward VII

Archduke Francis Ferdinand and Sophie

Emperor Charles

Emperor Francis Joseph on his deathbed

Preface

‘I am spared nothing’, Emperor Francis Joseph of Austria is reputed to have said in June 1914, soon after being told the news that his nephew and heir, Archduke Francis Ferdinand, and his wife had been assassinated at Sarajevo. It was an echo of the words attributed to him almost sixteen years earlier after another assassination in the family, that of his own wife Empress Elizabeth, in Geneva.

The Emperor had indeed been spared little in his personal life. The violent murders of his wife and nephew had been preceded in 1889 by the suicide of his only son, Crown Prince Rudolf, and in 1867 by the execution of his brother Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico. In the longest reign of any European monarch of the last three centuries, almost sixty-eight years, he had also suffered two ignominious defeats in war, with Italy in 1859 and with Prussia in 1866. Both had done immense damage, albeit of a temporary nature, to his personal standing and that of the house of Habsburg, so much that he even feared abdication might be necessary. ‘Never was martyrdom borne with greater dignity and resignation’, wrote Walburga, Lady Paget, wife of the British ambassador to Vienna towards the end of the nineteenth century. ‘His one fault is his weakness, but why this accumulation of terrible misfortunes, of which none of Shakespeare’s tragedies equals the horrors!’ Yet he weathered the storms, and by the time of his diamond jubilee in 1908 he had come to personify his empire in the same way that his contemporary Queen Victoria embodied hers.

A conscientious, well-meaning ruler and a kindly man, he has often been dismissed as dull and unintelligent if not stupid. Beside his more mercurial, wayward and tragic relatives, at first glance his long life may look uninteresting to some. Consequently, as a subject for biography he has often been neglected. One only has to compare the number of books published about his contemporaries in England and Germany, Queen Victoria and Emperor William II, to appreciate the difference.

This book intends to show him as a man against his family background – the son of a forceful mother, the husband of a difficult, wilful wife, the father of three very different children (not including a daughter who died in infancy). It is also the portrait of a ruler who presided against the decline of the Austrian empire and a man of generally peaceful intentions, who ironically bore some responsibility for the start of what was at the time the most momentous conflict in European history, a war the consequences of which he did not live to see.

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the gracious permission of Her Majesty The Queen to publish extracts from material of which she owns the copyright; and the staff of the Public Record Office to quote from material in their possession. Sue and Mike Woolmans have been extremely helpful with regard to supplying illustrations and information during the writing of this book, while Coryne Hall, Karen Roth, Katrina Warne and Robin Piguet have also given invaluable advice and encouragement at various stages. As ever I am also indebted to the staff of the Kensington & Chelsea Public Libraries for access to their collection; and to my editors at Sutton Publishing, Jaqueline Mitchell, Jane Entrican and Anne Bennett.

Last but not least, many thanks to my wife Kim, who cheerfully accepted my afternoons, evenings and very early mornings ‘in Habsburgland’ on the computer (to say nothing of hours spent trying to fix computer problems – thanks also in this regard to Hannah, Caroline, James, Andy and Phil). She and my mother Kate provided unfailing encouragement and interest throughout, and without their work in reading the manuscript in draft form, the end result would surely be much the poorer.

*Only the wives of Francis II and Charles Ludwig whose children were of major dynastic significance are included in this table.

ONE

Sovereign in Waiting

Archduke Francis Joseph was born on 18 August 1830, third in line to the imperial throne of Austria after his uncle, Emperor Ferdinand, and his father, Archduke Francis Charles. This was the infant on whom would rest the future of the house of Habsburg, a dynasty which could trace its lineage back through several centuries, but with an increasingly chequered history by the early nineteenth century.

In 1792 Emperor Francis had been crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Frankfurt, the Holy Roman empire being in effect a hereditary possession of the Habsburgs. With the proclamation of a republic in France that year, and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, Francis sought a title to assert his superiority over the upstart Frenchman and also his authority over his Habsburg dominions. When Napoleon proclaimed himself Emperor of France in 1804, Francis thought it politic to take an hereditary imperial title, which would appear stronger than the ‘elected’ office of Holy Roman Emperor, and he accordingly became Emperor of Austria. His country’s defeat at the battle of Austerlitz in 1805 resulted in a settlement which left Austria considerably diminished in prestige, and the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine a year later led to the final dissolution of the Holy Roman empire, as well as Francis’s renunciation of the now redundant title. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, summoned to determine the shape of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon’s France, the constituent territories of the Austrian empire were agreed. In addition to Austria and Hungary, they included Bohemia, Moravia, Galicia, Silesia, Slovakia, Transylvania, the Bukovina, Croatia-Slavonia, Camiola, Gorizia, Istria, Dalmatia, Lombardy and Venetia.

Though the empire comprised eleven nationalities, with little geographic and economic unity, it emerged from the Congress of Vienna greatly enriched. It was the intention of the statesmen who had met in Vienna, particularly the Austrian foreign minister Prince Clemens von Metternich, to maintain the European status quo. Austria, he maintained, had a historic right to be the major standard bearer of the principle of legitimacy, of leadership on the continent. After more than two decades of conflict the major European powers were exhausted, and anxious to ensure that France should no longer be in a position to threaten Europe again. They did this mainly by surrounding her with states of equal if not greater power. The Austrian and Russian autocracies had survived, and Prussia was now more powerful, having absorbed some Saxon territory and with a new commanding position on the Rhine, in order to forestall French expansion across the northern Alps. With its possessions of Lombardy and Venetia in Italy, Austria likewise acted as an obstacle against French designs in the south. In addition, it assumed leadership of the confederation of German states.

Emperor Francis had been married four times and fathered thirteen children, but only two sons and five daughters survived infancy. All were the issue of his second wife, Maria Theresa of Bourbon-Naples, a first cousin twice over. Though not generally recognised at the time, such inbreeding was to have serious implications for the family, some members of which were physically or mentally deformed. At the time, the blame for such shortcomings was attributed to other factors that sound less credible today. For example, the mentally deranged and extremely ugly Archduchess Marie’s problems were said to be a result of her mother having been chased during her pregnancy by an orang-utang from Vienna’s Schönbrunn zoo.

The elder son and heir, Crown Prince Ferdinand, was a well-meaning, simple-minded soul and a victim of epilepsy. With his ugly shrunken figure and unnaturally large head, he could barely utter two connected sentences, lift a glass with one hand, or descend a staircase without assistance. In December 1830 the court physician Dr Stifft told him there was no medical reason why he should not marry, but warned the rest of the family that it was unlikely he would or could ever make any effort ‘to assert his marital rights’.1 Two months later he married Princess Anna Maria of Savoy, who was said to be ‘white as linen’, and with a voice that shook perceptibly at the marriage ceremony. He reputedly suffered several seizures on the wedding night. The second in line to the throne, his brother Archduke Francis Charles was mentally and physically sound but regarded as a somewhat lightweight personality.

At one of the regular family gatherings comprising the Habsburgs and the Wittelsbachs (the royal house of Bavaria), Francis Charles became particularly attached to his cousin Sophie, daughter of Maximilian I, King of Bavaria, and his second wife Princess Caroline of Baden. The Bavarian children included two pairs of twin daughters, one of these younger twins being Sophie. She and her five sisters had a reputation for being strong-willed and authoritarian by nature, and the Prussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke would later refer to them collectively as ‘the Bavarian sisters of woe’.

Francis Charles was clumsy, shy and not particularly handsome, with a long thin face out of all proportion to his slight body. Well meaning but rather slow on the uptake, he made no impression on Sophie at first. She adored her mother and her twin sister Marie, and at first any thoughts of marriage were far from her mind. But the Archduke would not be put off, and he travelled regularly from Vienna to Munich to be with her. He sent her presents and wrote her affectionate letters, which she answered politely without guessing his intentions. Thus encouraged, he plucked up the courage to ask her for her hand in marriage. She could hardly refuse, but as the time drew near for her to leave home, she was so distraught that she said farewell to all her friends as if she was about to take her leave of them forever. The thought of living far away from her family with a man of whom she was not particularly fond, and whom she did not yet know that well, appalled her. However, the proposal had been made and could not be withdrawn. Being second in line to the throne of Austria, and likely to become Regent when his brother Ferdinand succeeded to the crown, the Archduke was one of the most eligible bachelors in Europe.

The wedding was to take place in November 1824, and Sophie was pleasantly surprised by her rapturous welcome in Vienna. Moreover, she found encouragement in seeing that her diffident husband-to-be clearly acted with more confidence in his own homeland. It touched her that he was always thinking of surprises for his bride, constantly buying her fine dresses, coats, jewellery and ornaments. Soon she was clearly becoming besotted with the suitor whom she had at first regarded with little more than indifference. His mother-in-law, Queen Caroline of Bavaria, liked him but was not blind to his faults, calling him ‘a good fellow’ who wanted to do well, but in the same breath saying he was ‘really terrible’ and that ‘he would bore me to death. Every now and then I would want to hit him.’2

Opinion is divided on Sophie’s attitude towards her husband in the early days of her marriage. Some said that at first she barely tolerated him, and only the presence at court of their nephew François, Duc de Reichstadt, the short-lived tubercular son of Napoleon Bonaparte and her sister-in-law Archduchess Marie Louise, proved her saving grace at Vienna. Others suggested that what had at first appeared to be a loveless match developed into a very happy marriage.

As she matured Sophie became ambitious and optimistic, and clearly cherished hopes of becoming Empress. When her mother asked her soon after her marriage if she was happy, she replied, ‘I am content’, a restrained remark which some misinterpreted as lack of enthusiasm. What did disturb her peace of mind were any threats to the old order elsewhere in Europe. When the Bourbons were deposed in France, she prayed for the divine destruction of revolutionary Paris, and regarded the Orléans regime as ‘illegitimate’. She also lambasted her Hanoverian contemporary King William IV for his ‘liberal stupidities’ in presiding over the Great Reform Act in England.3

Personal frustration was probably responsible to some extent for such intolerant behaviour. The couple dearly wanted a family, and during their first five years Sophie had five miscarriages. She underwent a number of cures in Ischl, and when another pregnancy was confirmed early in 1830 the doctors ordered her to take particular care of herself. Despite her longing for some fresh air, they insisted that she stay indoors during the long hot summer months. Some years later, after her name had become a byword for cold-hearted authoritarianism, a story was told that in the later days of her pregnancy, she threw the scalding contents of a cup of coffee in her husband’s face, and told him that she would be delivered of a child on only one condition – that a free pardon was granted to some prisoner under sentence of death. The only Austrian subject who fitted this criterion was guilty of some of the worst crimes imaginable, though unspecified, but he was still released from prison as a result of her intervention.4

In mid-August the long-awaited son arrived, and was named Francis Joseph, or sometimes ‘Franzi’ within the family. Almost from birth, he was granted his own apartment in the palace, though the rooms were en suite, with a never-ending procession of relations, servants and friends of the imperial family. His bedroom was situated above the guards’ lavatory, and at each change of guard drums rolled and bugles were sounded directly beneath his window.

Franzi was the eldest of five children. In July 1832 a second son followed and was called Ferdinand Maximilian, though always known in the family as Max. Charles Ludwig was born in 1833, and a daughter Maria Anna in 1835. Her brothers were all healthy, but their sister was delicate from birth. Though the doctors did their best to reassure her that the baby girl would probably grow out of her complaint, Sophie realised that she suffered from the hereditary taint of epilepsy. By the time she was four, she was so ill that the physicians recommended her hair should be cut off and leeches applied to her forehead. It was to no avail, and within a few weeks she was dead. Franzi shared in his mother’s grief, showing sympathy and understanding beyond his tender years. Max was puzzled at seeing their mother weep openly for the first time. Desperate to console her, he spent a month’s pocket money on buying her a pet monkey, and as he presented it to her he apologised profusely for being unable to buy her another little girl.5

At the time of her daughter’s death Sophie was expecting another child, and gave birth to a stillborn son a few months later. Late in 1841 she knew she was pregnant again, and in May 1842 she had a fourth son, named Ludwig Victor. Having already lost two children, and aware that her childbearing days were probably over, she devoted herself completely at first to this new son, with a maternal love that bordered on the obsessive.

Although their early years were thus not free from sadness, by and large the young Habsburg Archdukes enjoyed a carefree, happy childhood. Francis Charles was a doting father, and enjoyed galloping about the nursery with little Franzi on his back, taking him to the park to feed the deer, or helping him entice pigeons to the windowsills of their apartment in the imperial palace, the Hofburg, by putting out scraps of bread or seed. Every evening the boys would play hide and seek or similar games around the corridors, or sit at their mother’s feet while she read aloud to them from such titles as Gulliver’s Travels and The Swiss Family Robinson. When they were a little older, both parents took them for outings, walks, visits to the theatre and exhibitions in Vienna. While the importance of good behaviour in public was impressed on them, they were allowed to move freely and informally around in the family circle, and were never banned from the adults’ rooms.

On birthdays and name days the whole Habsburg clan gathered in the Hofburg for family feasts and exchanging of gifts, and the younger members performed in carefully drilled ballets, amateur theatricals, tableaux and recitations. With his gift for mimicry, his fine singing voice and outgoing charm, Max always enjoyed these the most. Sophie ensured that Franzi played the leading role as befitted the eldest brother, even though he had little talent for or love of acting. He was, however, the best dancer, and with his fondness for uniforms and fine clothes he was very proud when allowed to appear at a ball wearing tails for the first time. Max could not resist making fun of him, and after attracting everyone’s attention by mimicking the affectations and poses of the dancers, he seized his brother’s tails and made them both gallop round the edge of the ballroom.

Each year on Christmas Eve the whole family would gather outside the closed doors of the Emperor’s apartments, the younger children trying to glimpse through the keyhole the Christchild leaving gifts. When the Christmas bells rang, the doors of the Red Salon were flung open. There stood an enormous lighted tree with generous imperial gifts: a perfect child-size carriage, large enough to be drawn by a small pony; or a palace guard in miniature, complete with sentry boxes, drums, and toy guns. All evening Francis drilled his archduke uncles. After Christmas, during carnival, there were children’s balls, tables laden with sweetmeats, and the gayest of waltzes and polkas. At the end all the adults joined in the fun and games.

After Easter, when the weather improved and the days lengthened, the children could spend more time in the gardens of the Schönbrunn Palace, the imperial summer residence, riding in their donkey cart, swimming in the river, playing in the Indian wigwam one of the gardeners had made for them, or visiting a collection of exotic animals the Emperor had bought from a circus.

As infants, the Archdukes had their own household. Less than two years separated Franzi and Max, and they were entrusted to the same governess, Baroness Louise von Sturmfeder (‘Aja’). She was devoted to her charges, and felt sorry for Franzi with his lack of privacy, lamenting that ‘the child of the poorest day-labourer is not so ill-used as this poor little Imperial Highness’.6 Several others worked under her, including an assistant nurse, cook, chamberwoman, two maids and two footmen. Her diary gives some glimpses of the future Emperor in his earliest days. His favourite toys were a tambourine and a drummer girl given to him as Christmas presents when he was very small. A stoical child, he seemed much less concerned than everyone else when he arrived back from a walk in the park one bitter November afternoon with hands blue from cold because nobody had thought to give him any gloves.

Francis, Max and Charles Ludwig all enjoyed good health but Ludwig Victor was a sickly child, and his frequent bouts of illness gave his parents many an anxious moment, fearing they might lose him like his sister. Accidents and infections often kept him confined to bed for days if not weeks at a time. While ailing young archdukes and archduchesses were generally ministered to by nurses, Sophie was unusual in looking after him herself much of the time, rarely leaving his bedside if he was not well. If he was in bed during Christmas, she would postpone the main celebrations until he was able to take part. If the three elder brothers ever resented the fuss made of the baby of the family, they never showed it. On the contrary they were devoted to him, often bought him toys from their pocket money, and sometimes got together to stage small masquerades or theatrical performances for him. He showed his gratitude by regularly interrupting them while they were meant to be engrossed in their homework, and perhaps not surprisingly they were never reluctant to complain.

It was clear from early on that the down-to-earth Francis would be a soldier. Even as a toddler he loved military ceremonial, from sentries pacing beneath the nursery window each day, to the sound of bugle calls and the sight of parade-ground drill at the nearby barracks. From the age of four he enjoyed dressing up in uniform and playing with his toy soldiers. It was not long before he formed a collection in which every regiment of the Austrian army was represented, with the details of each uniform perfectly reproduced, and none of these soldiers was ever broken. By contrast the dreamy, more imaginative Max was always much more interested in the animals, birds and flowers to be seen near the palace.

From an early age, all four brothers were quite different from each other. Franzi was the most handsome and intelligent, with a strength of character and clear sense of self-discipline. Conscientious and hard-working, he had the utmost respect for authority. Max, romantic and given to daydreaming, was Sophie’s favourite. As the second son who was unlikely to succeed to the throne, he could afford to be mischievous, the one who could never resist seeking out their tutors’ weaknesses and teasing them mercilessly. If Franzi was their mother’s strength, Max was her delight. Charles Ludwig (‘Karly’) was intelligent but lazy, greedy, lacking in self-motivation, interested in nothing but sport and shooting. Ludwig Victor (‘Bubi’), weak and effeminate, was often grossly spoilt as the youngest.

The family spent the spring and autumn months at Schönbrunn and their retreat of Laxenburg, outside Vienna. Franzi and Karly preferred the latter where they could go shooting wild ducks and rabbits with their father. Maximilian liked Schönbrunn best, where he could always visit the zoo full of strange animals and the conservatory full of scented tropical plants. Every summer they moved to Ischl, a little mountain resort in the Salzkammergut, where they lived in a rented villa by the River Traun. Sophie believed in the therapeutic qualities of the Salzkammergut’s saline springs, which she swore had helped her become pregnant after years of miscarriages.

In February 1835 Emperor Francis celebrated his sixty-seventh birthday with a great court ball. A few days later he and the Empress attended the Burgtheater on an exceptionally chilly evening, with a sharp wind throughout Vienna, and within forty-eight hours he was confined to his bed with pneumonia. Some years before, it was said, Dr Stifft had examined him when he was suffering from a severe cold, but assured him there was no cause for alarm, as he was strong and there was ‘nothing like a good constitution’. Presumably with tongue in cheek, the Emperor retorted that he had no wish to hear that word again, on the grounds that he had no constitution and intended never to have one. Nevertheless this time he would not recover and he died on 2 March, to be succeeded by the charming but pathetic Ferdinand. The views of those who did not know him were summed up by Lord Palmerston, at the time British foreign minister, who called him ‘a perfect nullity; next to an idiot’.7 The Duc de Reichstadt thought him ‘a pathetic child, feeble-minded but fundamentally good at heart’.8

On his deathbed, Emperor Francis had signed two documents addressed to his son and successor. One entrusted him with defending and upholding the free activity of the Roman Catholic Church, and the other was a political testament in which he insisted that Ferdinand should take no decision on public affairs without consulting Prince Metternich. He also charged his brother Ludwig with presiding over the Council of State that would govern in Ferdinand’s name. This was a surprise as three of the Emperor’s surviving brothers were considered more able than the Emperor himself. Charles was a capable military commander, Joseph had showed himself a successful governor of Hungary, and Johann was a brave soldier and patron of arts. Francis had chosen the least capable of his brothers to guide his successor throughout his reign, giving Metternich absolute power, since the three Archdukes who had opposed him were put aside.

Such was Sophie’s respect for the memory of Francis that she made no criticism of his request, dictated by the wily Metternich, in which Ferdinand had been recognised as his successor. Privately she found it hard to forgive the statesman for thus promoting the succession, which was perfectly lawful but which she felt should have gone to her husband. While she had no illusions as to her husband’s ability, she wanted him at the forefront as trustee of their eldest son’s interests. All she could do was wait until their children reached manhood, and meanwhile she devoted herself to their upbringing. She strove to impress on them that in spite of the pathetic figure of the Emperor in his sovereign robes, his face distorted by constant epileptic attacks, the Habsburg empire was still the centre of the civilised world. This was easier said than done, when from early days they had to help at the imperial dinner table and watch their uncle Ferdinand. Looking at him, Sophie admitted to her mother, sometimes made her feel physically sick. On the question of her sons’ education, Sophie relied on nobody but herself, least of all her ineffectual husband. Although she disliked Metternich as he had excluded Francis Charles from the Council of State, she knew they could not do without his formidable political talents.

In 1836, two of Metternich’s closest friends were chosen as governors to Sophia’s sons. Count Heinrich Bombelles was appointed to supervise the education of Francis and his brothers. Each of the boys had their own special tutor or personal chamberlain as well, and Count Johann Coronini-Cronberg filled that role with regard to Francis, becoming responsible for the boy’s military training. Playmates were chosen for the young Archdukes, namely Marcus and Charles, the sons of Bombelles, and Francis, Coronini’s son. Coronini saw that Francis Joseph was timid and anxious and took it upon himself to give him a sense of pride and teach him self-mastery. A true nobleman, Coronini told him gently but firmly, could never yield to the plebeian vice of weariness, but always had to follow ‘the example of those self-controlled aristocrats who, in service in the field and the Court, had been able to conquer every weakness of the body’.9

Bombelles devised a programme of study for his charge. At the age of six, he was expected to spend eighteen hours a week studying from his books, increasing to thirty-six or thirty-seven at the age of eight, and forty-six hours at eleven. When he was thirteen, he became seriously ill, and the physicians put this down to stress induced by an over-taxing educational regime. After a suitable break he was given additional subjects to study, and by the age of fifteen he was working between fifty-three and fifty-five hours a week. The importance of early rising and punctuality was impressed on him. In the summer, lessons began at 6 a.m., and continued with short breaks until 9 p.m.

Considerable emphasis was placed on learning by rote, and little – perhaps too little – on how to think for himself. Baron von Helfert, a contemporary courtier and historian, thought the teachers could have been chosen better. In his view, they were ‘men of no deep culture or preparation, with a weakness for hollow affirmations’. Their standards of instruction were poor, and the boys were inclined to make fun of them. The history lessons, in particular, were ‘a spiritless mixture of sacred and profane history, with much scrambling up and down genealogical trees; a dry enumeration of events, with careful avoidance of any stimulus to original thought’.10 However, while these history lessons imbued Francis with a sense of the divine omnipotence of the sovereign, they also brought him up with the immovable concept that a just monarch was a good monarch; an emperor had obligations towards his subjects, and foremost among his duties was to protect them from injustice.

When seen alongside the more liberal educational regimes and syllabi devised for Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and for Francis Joseph’s contemporary, Prince Frederick William of Prussia, it was a narrow one somewhat lacking in systematic liberal and scientific or artistic content. Chemistry and technology were taught, but all as a haphazard collection of facts in which the emphasis generally appeared to be part of a process of learning facts for the sake of it, rather than as part of an integrated programme. From necessity there was more provision made for learning the different languages within the empire, and as he would need to be able to converse with peoples outside the empire, he was required to learn French as well, but never English. Otherwise the curriculum had changed little from what the boy’s grandfather had been taught in his childhood. In due course, his education was widened to include philosophy and spiritual matters from the court chamberlain, Joseph Colombi, and Abbot von Rauscher, a close friend of Archduchess Sophie. As Francis Joseph was a prospective ruler, it was felt that he would never need to appeal directly in person to his subjects or their representatives, and the art of public speaking was therefore considered unnecessary.

The education followed strict religious lines, and he remained a lifelong, unquestioning believer in the Catholic Church. His attitude to religion, it was said, was that of almost every Austrian gentleman of old nobility. To him, Catholicism was ‘as natural and obvious as the mountains of his country or any of the great given facts in the landscape of his life. One does not talk much about it; nothing is less liked in settled Austrian circles than any sort of talk about faith, whether popular or scientific.’11 Yet he lacked any intense religious fervour, and of all the family, only his brother Charles Ludwig became a passionate Catholic.

By the time of his eighth birthday Franzi was writing letters to his mother in French. At twelve he was learning Magyar and Czech as well as French, with Italian and the rudiments of Latin and Greek later. Unlike Max he never showed much interest in literature or reading, but enjoyed drawing, and made a series of sketches in Italy after his fifteenth birthday. As an adult he showed little interest in the visual arts, taking the view that painters should be decorators, producing meticulous pictures that celebrated military victories or faithfully reproduced familiar landscapes. In boyhood and adolescence he and Max enjoyed regular visits to the theatre, and Franzi liked dancing, though music excited little interest in him, apart from military marches.

Franzi was not a born soldier, and had to be taught to fill the role. Naturally reserved, quiet and shy, he had to be forced to mount a horse, often weeping bitterly from fear. It said much for his self-control and determination, as well as his tutor’s persistence, that he became a proficient and fearless rider.

At the age of thirteen he became colonel-in-chief of the 3rd Dragoon Regiment, and a year later he was allowed to ride at the head of his regiment when it was participating in exercises in Moravia. In 1845 Franzi, Max and Charles Ludwig were sent on what amounted to an official tour of Lombardy-Venetia, under the supervision of the respected veteran commander Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky. He staged reviews, firework displays and exhibitions of horsemanship for the young imperial visitors, as well as conducting tours of various defence works. Despite the Italian resentment of Austrian rule in the provinces, they were enthusiastically cheered when they appeared on an excursion down the Grand Canal in Venice, escorted by a small fleet of gondolas.

As adulthood beckoned, Francis Joseph was seen more and more in public. In January 1847 he was sent to Buda, Hungary, to represent the family at the funeral of his great-uncle Archduke Joseph. He had made good progress in learning Magyar, and his tact and apparent interest in everything he saw on his travels made the right impression. On two subsequent ceremonial occasions that year he was in Hungary again, making carefully rehearsed speeches in Magyar. At home there were other family funerals for aged relatives at which he would be seen riding at the head of his regiment, as well as various field exercises and court receptions.

In Vienna economic unrest during the 1840s, with poor harvests throughout Austria, mounting unemployment, and trading competition from Britain and Prussia, sowed the seeds of a depression which gradually spread from the poorer regions to more prosperous areas of the city. By Christmas 1847 Archduchess Sophie was in a state of profound gloom over the outlook for Austria. Her family connections included a half-brother on the throne of Bavaria, a twin sister as consort of the King of Saxony, and an elder sister married to King Frederick William IV of Prussia. She read several of the German newspapers and several French periodicals, and was probably the best-informed member of the imperial family. To her it was clear that younger politicians were impatient with the elderly Metternich’s conservatism, and within the Austrian empire the spread of a linguistic, cultural nationalism was creating instability.

Within the first few weeks of 1848, it was clear that events elsewhere in Europe were likely to provide a catalyst for change. There was insurrection in Sicily, liberal agitation in Tuscany and the Papal States, and a constitution was granted in Naples. In February Louis-Philippe, King of the French, was forced to abdicate. Early in March Lajos Kossuth, a Hungarian lawyer and journalist, made a speech to the Diet urging the establishment of a virtually autonomous Hungary with a responsible government elected on a broad franchise. While he spoke respectfully of the dynasty as a unifying force, he still considered it essential to change the character of government in the monarchy in order to safeguard the country’s historic rights, with constitutional institutions which recognised the different nationalities.

When reports of his speech reached Vienna, they produced the response of a plea for civil rights and some form of parliamentary government. Petitions were sent to the Emperor demanding the removal of police surveillance, and the dismissal of Metternich and his hated minister of police, Joseph Sedlnitsky. Early next day, a body of students marched on the Herrengasse. The army was sent out to quell the rioting, and four men were killed. Metternich was asked to resign, but refused to go unless his sovereign and the Archdukes in line of succession would personally absolve him from the oath he had taken before the death of Emperor Francis that he would give loyal support to Ferdinand.

This gesture of absolution required the presence of Archduke Francis Charles and his son Francis, and in this way the seventeen-year-old boy was admitted into the inner counsels of government. On agreeing to resign, Metternich protested half-heartedly against calling his action a generous one, saying that he acted according to what he felt was right. Two days later he left Vienna and fled to England.

With some prompting from his wife, known behind her back with a mixture of awe and respect as ‘the only man in the Hofburg’, Francis Charles emerged as chief spokesman for the government, and urged the granting of an imperial constitution. Once this had been granted, he said, all subsequent political reforms could be deferred until full agreement had been reached on the basic instrument of government. Archduchess Sophie was concerned at this proposal, as she was already aware that their son was likely to ascend the throne before long, and she did not wish his powers to be limited by any concessions which might be seen to have been wrung from the imperial family at a time of desperation. She thought it better that they should wait until the popular agitation and celebrations of Metternich’s fall from power had died down. On the next day, Francis joined his father and the Emperor on a carriage drive through Vienna, designed to test the mood of the public. The reaction was mixed, with some cheers for the Emperor, but some sullen faces as well.

There were sporadic uprisings in various parts of the empire, especially in Hungary. Sophie was keen to send her eldest son away from the difficult atmosphere and what she saw as the sorry spectacle of their fugitive court, and in April she thought that sending him to Prague as Viceroy would be a suitable diversion, as well as giving him some official status. However, the unrest in that city put an end to the idea.

Knowing that his time was coming, she wanted to give him some conspicuous position that would put him more in the public eye. If he was closer to ‘the victorious and avenging sword’, but not too close for danger, somewhere connected with the Italian theatre of war would be ideal. In April the Wiener Zeitung announced that the Archduke would be joining Radetzky in order to see for himself ‘the Field-Marshal’s warlike preparations against enemies and agitators’. As Radetzky’s army was immobile at the time, it was merely a way of enhancing the prestige of the youth whom his mother was already grooming as the saviour of the imperial dynasty.

Sophie had made her plans without consulting the Field Marshal who, despite his loyalty to the Habsburgs, was still prepared to speak his mind and vent his indignation. He coldly told the young Archduke on his arrival that his presence only made matters difficult for him. ‘If anything happens to you, I am to blame; and if you are taken prisoner, I and my army are lost.’12 He ensured that Francis Joseph was kept out of harm’s way as far as possible, and entrusted him to the care of Lieutenant-General d’Aspre, on whose staff the young Prince remained. He received his baptism of fire on the battlefield in May when the Piedmontese army launched three assaults on the Austrians in the village of Santa Lucia. Almost 400 men were killed in the skirmish, but the young Archduke was said to have remained calm and collected though not far from the cannon fire.

By May workers’ and students’ demonstrations, fuelled by sympathy for the nationalist aspirations of the Italian territories and Hungary, had made the atmosphere in Vienna so tense that the imperial family were advised to move under cover of darkness from Vienna to Innsbruck, where they remained for the next three months. Soon after their move Sophie’s sister Ludovika, Duchess in Bavaria, came to visit them, accompanied by her daughters. Helene was fourteen and Elizabeth ten. It was the first time Francis Joseph had met his Bavarian cousins, but they made no particular impression on him. On 18 August he attained his majority, and his eighteenth birthday present from his parents was a pair of decorated meerschaum pipes.

That autumn Theodore Latour, minister of war, gave orders for part of the Vienna garrison to assist in the subjection of Hungary, where resistance to Habsburg rule had been hardening. This prompted demonstrations by the radicals in Vienna, and violence erupted once more in the city. A mob seized Latour from his office, stabbed him to death and hung his naked body on a lamppost in one of the city squares. Again, the imperial family were advised that temporary retreat would be prudent, and they departed for the garrison town of Olmütz.

In the last week of October Field Marshal Otto von Windischgrätz massed his army to surround the city and subjected it to a prolonged bombardment. The resistance of the radicals soon evaporated, and in the ensuing disturbances between 2,000 and 3,000 were killed. Within a few days the city capitulated to the troops. Over twenty suspected ringleaders of the revolt were shot, and throughout the winter the city remained under strict military control.

Another family conference took place, dominated by Archduchess Sophie whose plans coincided perfectly with those of chief minister Prince Felix Schwarzenberg, Windischgrätz’s brother-in-law. The latter would only accept office under a new emperor, and it was confirmed that, in accordance with discussions held earlier that year, Ferdinand would shortly be asked to abdicate. Through no fault of his own, he was clearly unfit to reign, particularly at a time of such instability, and especially as he was seen as the imperial personification of the system against which the Viennese had rebelled. Archduke Francis Charles had been found wanting. In an age of peace he would have made an adequate Emperor, but in exile he had been a grumbler, indecisive and no match for revolutionaries who threatened the fabric and stability of the empire. Much as she had longed to be Empress, Sophie realised that it was not to be. Instead she would be the mother of an Emperor. Francis Charles was easily persuaded to renounce his place in the succession, doubtless relieved that the responsibility would never fall on his shoulders.

On 2 December 1848 the family and ministers were summoned to appear before Emperor Ferdinand in the salon of the Prince-Bishop’s palace at Olmütz. In his halting, at times barely coherent, voice he read out the official act of abdication handed to him by Schwarzenberg. He surrendered his Austrian imperial titles and the crowns of Hungary, Bohemia and Lombardy, while still retaining the personal style and dignity of Emperor. Schwarzenberg then read Archduke Francis Charles’s formal renunciation of his place in the succession, announcing that at this moment in the Habsburg history, a younger person was needed. Francis Joseph was untainted by association with the events of the last few months, and could serve as the symbol of a new era in the history of the Austrian empire. The ceremony ended with the new Emperor kneeling to his predecessor and asking for his blessing. Ferdinand laid his hands upon the youth’s head, made the sign of the cross, then embraced him as he told Franzi that God would protect him.

Emperor Ferdinand and Empress Anna Maria, doubtless pleased to relinquish their responsibilities, went to hear Holy Mass in the palace chapel, and then left for Prague, where they settled in Hradschin Castle. Ferdinand lived at Prague till his death in 1875, and was known affectionately as ‘der Praguer Majestas’, to distinguish him from his nephew.

Meanwhile, Archduke Francis was proclaimed ‘by God’s grace’ Francis Joseph, Emperor of Austria. By not styling himself simply Emperor Francis, but adding the name of his much-revered progressive grandfather Emperor Joseph II, it could be inferred that he was planning to follow in the latter’s footsteps and become a constitutional, reforming monarch. He inherited a generous collection of sovereign titles – King of Jerusalem, Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Bohemia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Lombardy, Venetia, Illyria and Croatia, and Grand Duke, Duke, Margrave, Prince and Count of some thirty other territories in the huge Austrian empire with its 35 million inhabitants. Some contemporary wits found this panoply amusing, if not faintly absurd. According to an old Austrian joke, ‘The King of Croatia declared war on the King of Hungary, and Austria’s Emperor, who was both, remained benevolently neutral.’13

A proclamation to the new emperor’s subjects, almost certainly drafted by Schwarzenberg, took place with a flourish of trumpets outside the Rathaus (town hall), and a little later on the steps of the cathedral. In it the young monarch announced that they (as opposed to he himself) were

convinced of the need and value of free institutions expressive of the spirit of the age

and that they entered

with due confidence, on the path leading to a salutary transformation and rejuvenation of the monarchy as a whole. On the basis of genuine liberty, on the basis of equality of all the nations of the realm and of the equality before the law of all its citizens, and of participation of those citizens in legislation, our Fatherland may enjoy a resurrection to its old greatness and a new force. Determined to maintain the splendour of the crown undimmed and the monarchy as a whole undiminished, but ready to share our rights with the representatives of our peoples, we count on succeeding, with the blessing of God and in understanding with our peoples, in uniting all the regions and races of the monarchy in one great state.14

TWO

‘Physically and Morally he is Fearless’

According to legend, when Emperor Francis Joseph returned from the ceremony which confirmed his accession to the throne he burst into tears, saying ‘Farewell my youth’. The serious young man was already somewhat old for his years. At once he bowed to the demands of his office. Before dawn each morning he sat at his desk to deal with official papers, a routine to which he would adhere for the rest of his long life.

Yet he had not completely bidden farewell to his youth, or at least his youthful spirits. Not long after his accession, his brothers were playing in the audience chamber of the palace with a ball, and Ludwig Victor accidentally threw it straight through a mirrored door just as his mother and eldest brother were entering the room. Dreading a scolding and in tears, he was about to apologise when the Emperor astonished them by turning to Sophie and asking for her permission to help them smash the door down. Like a good subject, as well as an indulgent mother, she allowed them to do so. Her sons proceeded to shatter it beyond repair, the young Emperor leading them with suitably boyish enthusiasm. What would the Bishop think of those vandals who were her sons, Sophie asked herself, not knowing whether to laugh or cry.1

It was probably her eldest son’s last outburst of high spirits. A few weeks later he, Max and two of their cousins were returning from a military inspection one day in bright sunshine. Max and the two younger boys enjoyed a snowball fight in the gardens but Francis Joseph stood apart, laughing at their antics but stopping short of joining in.

As Emperor, albeit a youthful one, more weighty matters demanded his attention. The Hungarian resistance had to be broken, or at least quelled, if order was to be restored to the empire. By the first week of January 1849 the Austrian forces under Windischgrätz controlled the twin Hungarian capitals of Buda and Pest. In April Kossuth proclaimed ‘the deposition of the house of Habsburg’ in Hungary and moved his revolutionary government eastwards to the town of Debrecen. A Hungarian delegation offered to discuss a settlement, but the Field Marshal replied that there could be no negotiations with rebels. Two weeks later, he confirmed to the Emperor that victory was theirs.

The young Emperor grew rapidly in self-confidence. His elders had assumed that he would be a mere rubber stamp, content to agree to any ideas put forward or documents put in front of him without consideration, and that he would be a tool of his mother, or of Prince Schwarzenberg. Both exercised a lifelong influence on the autocrat, in theory one of the most powerful rulers on earth, yet still little more than a boy. But he surprised them all by presiding over meetings in person. That spring he decided, against the advice of Windischgrätz and Schwarzenberg, to ask Tsar Nicholas to come to Austria’s assistance by despatching a Russian expeditionary force to help put down the simmering rebellion in Hungary. The Tsar met Francis Joseph in May 1849, and wrote to the Tsarina telling her how impressed he was with the young ruler. ‘The more I see of him, the more I listen to him, the more I am astonished by his intellect, by the solidity and correctness of his views. Austria is lucky indeed to possess him.’2