Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Hesperus Press Ltd.

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

After a childhood marked by loss and grief, Hölderlin studied theology in the illustrious company of Hegel and Schelling, before concentrating on poetry and writing his most famous work, Hyperion. But, afflicted by the pressures of life and a doomed love affair, he gradually went mad, and spent the final thirty-six years of his life in a solitary tower in Tübingen, cared for by a kindly carpenter. The younger poet Wilhelm Waiblinger (1804–30) was one of the few people to gain Hölderlin's confidence, and visited him often; this is his beautifully written memoir of the stricken poet, a unique insight into his personality, sensitively translated by Will Stone.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 88

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

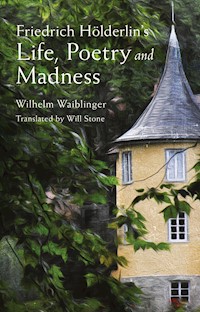

Friedrich Hölderlin’sLife, Poetry and Madness

Wilhelm Waiblinger

Translated by Will Stone

Friedrich Hölderlin by Luise Keller, 1842

Contents

Introduction

But the more perceptive man? Oh, he who began to perceive and is silent now – exposed on the mountains of the heart …

RILKE

In the Protestant Cemetery of Rome, famed as the resting place of those ‘matchless singers’, the English Romantic poets Keats and Shelley, lies another, lesser-known Romantic of equally tender age. He is the German poet Wilhelm Waiblinger, who was laid to rest there in January 1830 aged only twenty-five, a probable victim of syphilis. Today Waiblinger is best known in terms of his relationship to the great German lyric poet Friedrich Hölderlin during the latter’s renowned seclusion from 1807 to 1843 in the now-named ‘Hölderlinturm’, the Hölderlin Tower in Tübingen, and for the essay memoir he wrote in 1827–8 about the stricken Swabian poet, entitled Friedrich Hölderlins Leben, Dichtung und Wahnsinn. Waiblinger never saw the essay published, for it did not appear in Germany until 1831, a year after his death.

Waiblinger, friend of another up-and-coming poet in the early 1820s, Eduard Mörike, was known as a rebel, a wayward fellow and a liberal maverick, an independent thinker. The two friends were theology students in Tübingen, in the very same Protestant seminary, the ‘Tübinger Stift’, where Hölderlin had studied alongside Schelling and Hegel from 1788. The young Waiblinger was naturally inclined to be anti-Establishment, to ardently follow the path of freedom, the writings he left behind fairly flash with anger and wilfully scatter their shards of disrespect; but the swashbuckling Waiblinger also happened to appear at a time when a certain frustration with the prevailing culture was already in the air. Huge movements in philosophy and poetry were afoot and Hölderlin was an instrumental figure within them before his reasoning was affected. The senior poet Hölderlin, the ultimate tortured outsider, a high-flown spirit broken by fate, doomed to a life of semi-sequestration, raving in madness at the injustices which befell him and pacing alone in a tower, must have seemed to Waiblinger like an overwhelmingly seductive subject and a dramatic portent of the sort of punishment that might await him should he not take control of his already chaotic life.

During the winter of 1827–8, after departing to Rome, Waiblinger penned what would be his historically valuable portrait of the older poet, drawn from his many visits to Hölderlin in his tower chamber in the early to mid 1820s. These visits apparently commenced in the summer of 1822 and ended in the autumn of 1826, roughly a four-year period, with the most intense series of encounters made over a year and a half through 1822–3. However, in his essay Waiblinger extends the period dramatically between last seeing Hölderlin and his departure for Italy, speaking as if he is looking back nostalgically on a distant epoch. Having encountered Hölderlin’s poetry and, most importantly, a new publication of his unclassifiable novel Hyperion, at age seventeen, Waiblinger resolved to seek out the now fifty-two-year-old author (then considered virtual old age) or the ‘Madman’ as he terms him in his diary, who resided but a stone’s throw away in the house of the benevolent carpenter Ernst Zimmer. His family having abandoned him, Hölderlin had been taken in by the culturally aware carpenter in 1807 after being released from the clinic of Dr Ferdinand Autenrieth in Tübingen, where he had been incarcerated since 1806 and was soon deemed incurably insane. On release the good doctors thanked Zimmer for his charitable gesture and gave his charge a mere three years to live. Zimmer had read Hyperion and obviously sensed something of the gravity of Hölderlin’s dire position in spiritual terms, so he resolved to accommodate him and attend to his needs. Part of his house beside the River Neckar contained a tower which had formerly been a defensive stronghold within the city walls. Here a simply furnished room on the first floor became home to the estranged poet for the prolonged latter stage of his existence. Waiblinger was an early visitor, one who was uniquely tolerated by the highly strung and nervous occupant of the tower. Having got over the initial horror of the spectacle of the eccentric Hölderlin before him, Waiblinger became more and more drawn to visit him, the man in the tower providing a living tragic figure onto whom he could project his own existential hopes and fears, his own preoccupation with madness and the danger of losing one’s self entirely. Gradually, through repeated visits, Waiblinger could begin to amass fascinating details of the day-to-day life of this curious victim of his own hypersensitivity, fleshing out a portrait or as close to one as could be expected of the ‘unfortunate’ during these years of seclusion.

Waiblinger became increasingly obsessed by Hölderlin through a combination of visits and reading the newly published single edition of Hyperion which had appeared in 1822. Waiblinger’s own attempt at a lyrical novel, Phaeton, from 1823 became his homage to Hyperion, and the hero is based around Hölderlin. In his diaries of the time, Waiblinger effuses over Hölderlin as a poet of the highest sensibility and ideals, a rare, noble mind, a mind possessed of a unique spiritual purity, whose verse proves infinitely intoxicating. On 7 August 1822 he states: ‘This Hölderlin disturbs me greatly. God, God! Such thoughts, this high-born pure spirit and this mad man! Hyperion is saturated with spirit: A fervent fully glowing soul swells there. Nature is his true divinity. He is endlessly original, ingenious. Hölderlin is dearer to my heart than Hölty, Neuffer, Weisser, Haug, Schwab, all of them put together. Hölderlin has been sent from heaven to be a poet on earth. Hölderlin shakes me to the core. I find in him an eternally rich form of sustenance.’ This sort of effusive entry continues during this period, when his reading of the elder poet is gradually forming into a mental kinship, apprentice and master. It is Hyperion above all which is the drug Waiblinger must have, though its potency in the end proves too much. ‘I cannot read it for long, for I go under in such a sea: I am stricken with vertigo, I’m shaken to the very core … my brain itself is on fire …’

But once Waiblinger had become used to the unconventional appearance and peculiar comportment of the strange figure in the tower room, he also began to feel genuine affection for the ‘Madman’ on a personal level, as comrades and fellow mavericks, as outsiders beyond the Establishment. But Waiblinger is still positioned on the living side of the Styx whilst Hölderlin had already been ferried across by Charon, but was now caught on a sandbank midway. Waiblinger may appear the sane, the scientific, the safe one, rooted in robust life, surveying the wreckage of Hölderlin from the gilded towers of Rome, but unknown to himself he is a marked man and has but months to live. The tragedy awaiting Waiblinger as he writes his memoir invests the piece with even greater pathos. The essay exhibits both the attempt to discuss Hölderlin’s spiritual decline in abstract scientific terms, from a detached observer’s point of view as it were, employing a philosophic, reflective tone, as well as through a more personal compassionate humanistic approach. Waiblinger, who was a rather unrestrained bohemian character and self-confessedly showed signs of mental strife himself (most often manifesting through the imbalance in his attitudes towards established literary figures), found in the fallen Hölderlin a human subject suffering likewise but on a higher level around whom his own Romantic idealisation and directionless spiritual intoxication could be bridled. Hölderlin was a lesson, a terrifying example of the physical and mental health potentiality of imaginative thought unrestrained. But the hunched survivor spewing gibberish that Hölderlin now was, this blown husk of a once-soaring spirit, now lost to inanities, effusive bowing and peculiar eccentricities, must also have seemed to Waiblinger something eminently dramatic in itself as an individual case of human tragedy. How could it be that such a personal torment and a degradation could be thus prolonged without death as the desired cauterising dénouement, and the ultimate tantalising question raised then of a possible cure, of some miraculous future restoration of sanity, if only temporary.

Hölderlin did not welcome visitors, especially new ones – this is made plain in Waiblinger’s account – so there was something about this fresh-featured, ardent young man that the reticent, suspicious Hölderlin warmed to: perhaps he saw himself as a younger man, we can but speculate. Waiblinger’s gushing praise for Hyperion must have been a key factor in this acceptance at the outset, but as time went by Hölderlin clearly developed an interest in or liking for the younger man, or at least his presence became a reassuring convention and thus a degree of mutual trust and expectation were established. One of the most moving sections of the essay concerns the walks the two made to Waiblinger’s rented summer residence, the Pressel garden house, romantically positioned on the Österberg above Tübingen. That Waiblinger even managed to persuade the notoriously unco-operative Hölderlin to accompany him such a distance was an impressive feat, which those who cared for the poet and were used to his intransigence were at pains to comprehend. And we are told that even after Waiblinger had left the vicinity, Hölderlin, on his walks with the carpenter’s daughters into the fields and meadows around the town, would still approach the garden house, knock on the door and enquire of Herr Waiblinger’s whereabouts. Through his regular comings and goings, Waiblinger appears to have been attempting to improve Hölderlin’s lot, almost administering a benign therapy of sorts. We hear how he listens to him read, tries to give him books, patiently endures his excruciatingly repetitive piano-playing, suffering the ghoulish clickety clack of his uncut nails passing back and forth across the keys, points out subjects of interest in the landscape, joins him in a conspiratorial smoke and the imbibing of wine and beer. Waiblinger seeks to bring this pained, disturbed and dysfunctional man back to some remembrance of normality, to make out the distant echoes of social interaction. Waiblinger is caught in a web of fascination for the tower man: a powerful mixture of pity, revulsion, fervour and admiration brings him back again and again.