Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

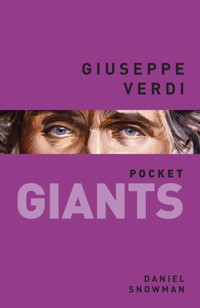

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) was the Shakespeare of opera, the composer of Rigoletto, Il Trovatore, La Traviata, Aida and Otello. The Chorus of Hebrew slaves from Nabucco (1842) is regarded in Italy as virtually an alternative national anthem – and the great tragedian rounded off his career fifty years later with a rousing comedy, Falstaff. When Verdi was born, much of northern Italy was under Napoleonic rule, and Verdi grew up dreaming of a time when the peninsula might be governed by Italians. When this was achieved, in 1861, he became a deputy in the first all-Italian parliament. While in his 20s, Verdi lost his two children and then his wife (many Verdi operas feature poignant parent-child relationships). Later, he retired, with his second wife, to his beloved farmlands, refusing for long stretches to return to composition. Verdi died in January 1901, universally mourned as the supreme embodiment of the nation he had helped create.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

1 Giant of History

2 Childhood and Early Career

3 The Years in the Galley

4 Verdi: In Private and in Public

5 ‘Viva VERDI!’

6 Home and Away

7 The Ageing Maestro: Life, Death and Afterlife

Notes

Timeline

Further Reading

Web Links

Copyright

1

Giant of History

I was taken to my first opera by my father. It was a week or so before my ninth birthday and the opera was Verdi’s Rigoletto, a rip-roaring work about sex and murder, two topics I did not yet know much about! However, I was perfectly capable of recognising big, bold passions as they came pouring across the footlights and, to this day, well over two-thirds of a century later, I still recall the overwhelming impact of my first exposure to this most ambitious and multimedia of art forms. The extravagant sets and colourful costumes, the big theatrical gestures and passionately projected voices, and above all Verdi’s energised, dynamic music with its muscular mix of bravado and pathos, ecstasy and anger, tears and ultimate tragedy: I devoured them all. During the first interval, my father turned to me, gently asking whether I had had enough and would I like him to take me home? No, I exclaimed with mock resentment, I do not want to be taken home, adding: ‘We haven’t even got to the bit that I know from your gramophone records: La donna è mobile!’ That night, I laughed with the lascivious duke, loved with the vulnerable Gilda and wept at the end with her bitter, bereaved father. Today, well over a thousand opera performances later, I still find myself deeply moved by a great performance of a great opera such as Rigoletto.

Opera is the art form which, historically, emerged from the attempt in late Renaissance Italy to combine and integrate all the others. Most of the operas produced in the centuries since have fallen by the wayside with only a tiny number – forty or fifty perhaps from among the many thousands that have been written – consistently retaining a place in the worldwide repertoire. Operas by Meyerbeer, once popular, are nowadays rarely performed, while some by Handel, long disregarded as unperformable on stage, have recently enjoyed an unaccustomed place in the operatic sun. A handful of composers (Bizet, Gounod, Mascagni, Leoncavallo) cling to operatic immortality primarily because of a single work that has managed to retain its popularity. But who can be said to have contributed a number of works to the universally accepted operatic repertoire? Mozart and Puccini certainly; Rossini, Donizetti and Richard Strauss probably. And then come the giants, Wagner and Verdi. Of this select band, probably the most widely performed, from his day to ours, is Giuseppe Verdi. My father was right to take me to Rigoletto, an opera that remains a mainstay of every self-respecting company in the world and has done so consistently ever since its 1851 premiere. Much the same is true of La traviata or works such as Il trovatore and Aida. Ambitious Verdi operas such as Don Carlos, Un ballo in maschera, La forza del destino and Simon Boccanegra, all of them packed with poignant, lyrical beauty punctuated by big-scene grandeur, continue to receive new productions in the opera houses of the world, while Verdi’s final works for the stage, Otello and Falstaff, two masterpieces with nothing in common except their Shakespearean inspiration, each provide a supremely powerful theatrical experience when produced with a cast capable of doing them justice.

But Verdi is not just a giant of operatic history or a massively creative artist. He also grew to become a giant figure in the history of his nation. When Italy achieved unity and statehood for the first time in 1861, Verdi was invited to become a deputy in the first all-Italian parliament and later made a senator for life. On his death in 1901, the old man was universally mourned as the supreme embodiment of the nation he had helped create, a beloved national treasure comparable with that other crusty octogenarian, Queen Victoria, who had passed away a few days before. A month later, as vast crowds poured into the streets of Milan to witness his progress to his final resting place, many people throughout Italy felt that Verdi’s importance to his country was as potent as his importance to his art.

***

Verdi died in the Gran Hotel et de Milan, just up the road from La Scala, on 27 January 1901. During his final decline, the city authorities covered the streets outside his hotel room with straw to dull the sound of horses’ hooves, and people began to congregate nearby as their beloved maestro sank gradually towards his inevitable demise. On the day of the funeral, as the cortege wound its way across Milan, the largest crowds the city had ever witnessed lined the route. Gently and spontaneously, they began to sing the chorus Va pensiero (from his opera Nabucco), Verdi’s paean to his beloved homeland penned nearly sixty years earlier as a coded anthem yearning for a united, independent Italy.

Thus the legend. And, like most legends, or clichés, it contains an element of truth. In fact, Verdi’s actual funeral was, as he had instructed, a relatively modest affair and he was initially buried in Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale. But a month later, to great pomp and circumstance, his body was transferred to lie (alongside that of his wife) across town in the crypt of the Casa di Riposo, the home for retired musicians that Verdi himself had founded and funded. As the cortege was about to leave the Cimitero, Arturo Toscanini, the 33-year-old principal conductor at La Scala, led a huge choir in a performance of Va pensiero. Some of those within earshot doubtless sang along, though press reports suggest the overall impact was diluted by the vast open-air space the choir had to fill – and the prolonged whistle of a locomotive at the nearby train station.1 As for the suggestion that this chorus was a surrogate national hymn – this may have been a common perception by 1901, but was hardly that back in 1842 when it was composed.

Much that happened in Verdi’s life remains clouded by myth or uncertainty, and the man himself, like many ageing celebrities, was not above adding to the mystique. ‘I am just a peasant, rough-hewn,’2 he would chuckle to visitors, seeming to forget that his father, Carlo Verdi, ran an inn, kept efficient accounts and, in a society in which most were illiterate, could read and write and afford to send his son to school. True, the family background was provincial, living as they did in a tiny village near what was a smallish town, but that was true of most Italians in those days. Different parts of the vast Italian peninsula were ruled by a series of remote, often foreign-based authorities whose writ tended to impinge upon village life far less directly than that of the landowners and priesthood of the vicinity. Life was, essentially, lived in the locality, with local people, local diet and local dialect. Even into old age, long after Italy had been united and its national language standardised, Verdi spoke and wrote Italian with occasional imperfections deriving from the regional dialect he had learned as a youngster.3 ‘Just a peasant’? No. But one can see why the wealthy celebrity of the 1870s and 1880s, feted in cities like Milan and Paris, might have said so when reminiscing about the remote flatlands of his early childhood.

The Verdi mythology starts with the date of his birth and the home in which he was raised. For over sixty years the composer told people that he was born in Le Roncole (‘the scythes’), a little village in the Po Valley near Busseto in the Duchy of Parma, some 65km or so south-east of Milan, on 9 October 1814. That is what his mother Luigia had told him. In fact, as his birth certificate attests, he had been born a year earlier, in October 1813 but (according to the ecclesiastical record in the local church as well as the civic record) more likely on 10 October. He was certainly born in Roncole, but not in the house with the slanting roof which, to this day, remains the official ‘birthplace’ of the great man. The family did live there, but not until the boy was in his early teens. And his baptismal name was not Giuseppe but Joseph; in 1813 the region was still under French rule and it was another couple of years before the baby could become ‘Giuseppe’ in the eyes of officialdom.4

Meanwhile, another somewhat mythologised event occurred. In 1814, the anti-Napoleon troops of the so-called Holy Alliance pushed their rough way across parts of northern Italy, including the Parma region. Many years later, the composer told a visitor how, when a contingent of Russian soldiers (perhaps Cossacks) came to occupy Roncole, their ‘outrages brought grief and terror’ to its citizens.5 Luigia Verdi took her baby son up a ladder into the bell tower of the local church to seek refuge, terrified that his crying would give them away. Fortunately, said Verdi, ‘I slept almost continuously and laughed contentedly when I woke up’. Maybe. There is no evidence that Russian troops were among the Alliance armies in this region. That did not, however, prevent many early chroniclers of Verdi’s life from speculating on the incalculable loss to music if the pair had been discovered – or (even worse) if the baby genius-to-be had been deafened by a sudden peal of bells.6

We must not read too much into the semi-truths embodied in these stories and others we will encounter later. Family records were invariably patchy in small-town Italy during the nineteenth century, and Verdi is probably no different from many of his contemporaries in giving credence to a series of questionable anecdotes passed down from one generation to the next. But two things are worth noting. First, because of the international stature Verdi went on to achieve, many of these myths soon found their way into what, until modified by recent research, was for long the universally accepted narrative of his life. Second, it becomes clear as one reads the detailed record that Verdi himself seems to have, I hesitate to say ‘lied’, but at least to have embellished, perhaps subconsciously, certain aspects of his personal history.

Every age has to recreate its own version of the past, seen through the agenda of a constantly changing present. We now know that some of what has long been believed about Verdi may be the result mythologisation, helped along in part by the ageing maestro himself. None of this in any way reduces the greatness of the man, however. On the contrary, the very fact that Verdi has long been regarded as one of the supreme visionary heroes of Italian unification and statehood, a genius who used his art to help better the fate of his compatriots, has itself long been incorporated into the narrative of Italian history. In what follows, we will try to separate demonstrable fact from resonant fiction, while allowing an important place for both. And, throughout, let us not forget that Verdi was a human being with his own needs and desires, fulfilments, frustrations and failings. This, to my mind, renders his achievements – as musician and man – all the more impressive.

Most creative artists are known to posterity by their artworks alone and, perhaps, by something about the lives they led. We may admire the works of Leonardo and Michelangelo, Shakespeare and Tolstoy, Mozart, Beethoven and the rest, and return to them again and again. None of these was ever regarded, in his own time or since, as a virtual embodiment of his nation, let alone a pivotal figure in its very foundation. Yet this is how Verdi was mourned on his death in 1901 and is how many continue to see him to this day.

2

Childhood and Early Career

Verdi was no infant prodigy, but he was obviously a bright lad and his parents were keen to give him a decent education. Initially, this meant visits to a friend and neighbour, a schoolmaster and sometime organist at the local church, who taught the boy a little basic Latin and Italian, and perhaps also helped introduce him to music – something for which he evidently showed early aptitude. Later, he attended the local village school. Giuseppe – ‘Peppino’ to those who knew him – was not a demonstrative youngster; rather the contrary. Shy, aloof even, he was ‘sober of face and gesture’, according to the memory of contemporaries, and tended to keep apart from the other youths, absorbed in his own thoughts and often preferring to be at home with his mother and young sister7 (who was to die when aged only 17).

When he was 8, Verdi’s parents bought him a battered old spinet which, he recalled later, ‘made me happier than a king’8 and which he kept lovingly throughout his life (it is preserved today in the museum of La Scala, Milan). Much of his spare time was spent in the nearby church where he sang in the choir and began to play the organ. He also served as an altar boy. One day at Mass, temporarily distracted by the music from the organ loft, he failed to respond to the officiating priest who angrily pushed the 6-year-old down the altar steps. Little Peppino let out a curse at the priest (‘May God strike you with lightning’) – and the priest duly died in a lightning storm some years later!9 True or false? It was certainly a story with which Verdi liked to regale visitors in later life, partly no doubt because it seemed to epitomise not only his love of music but also his inveterate anticlericalism.

When Verdi was 10, his parents sent him to further his education in nearby Busseto. On Sundays he would walk back to Roncole to see his family and to attend church, where he continued to play the organ. Later he recalled how, on one of these treks during the depth of winter, he fell into a ditch and thought he was going to drown until a passing peasant woman helped pull him to safety.10

Busseto was not a great deal less provincial than Roncole, but it was a proper town with a tradition of culture and commerce and, by this time, the ginnasio