Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

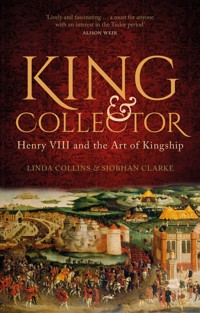

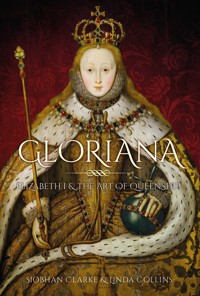

In a Reformation kingdom ill-used to queens, Elizabeth I needed a very particular image to hold her divided country together. The 'Cult of Gloriana' would elevate the queen to the status of a virgin goddess, aided by authors, musicians, and artists such as Spenser, Shakespeare, Hilliard, Tallis and Byrd. Her image was widely owned and distributed, thanks to the expansion of printing, and the English came to surpass their European counterparts in miniature painting, allowing courtiers to carry a likeness of their sovereign close to their hearts. Sumptuously illustrated, Gloriana: Elizabeth I and the Art of Queenship tells the story of Elizabethan art as a powerful device for royal magnificence and propaganda, illuminating several key artworks of Elizabeth's reign to create a portrait of the Tudor monarch as she has never been seen before.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Siobhan Clarke & Linda Collins, 2022

The right of Siobhan Clarke & Linda Collins to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9092 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Introduction: Gloriana

1 Elizabeth I and the English Renaissance

2 Family and Survival: The Early Years

3 ‘God Hath Raised Me High’: Accession and Religion

4 ‘One Mistress and No Master’: Marriage Game

5 Nicholas Hilliard: The Queen’s Painter

6 Secrets and Codes: Mary, Queen of Scots

7 Elizabethan Arts: The Golden Age

8 Gold and Glory: Exploration and Armada

9 Dress, Dazzle and Display: Mask of Youth

10 Final Years: Death and Legacy

Appendix: List of Artworks and Treasures

Bibliography

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses by Hans Eworth, 1569, oil on panel. Hampton Court Palace, London. © The Picture Art Collection/Alamy

2Elizabeth I as a Princess by Guillaume Scrots, c. 1546, oil on panel. Windsor Castle, Berkshire. © The Picture Art Collection/Alamy

3The Family of Henry VIII, An Allegory of the Tudor Succession, attributed to Lucas de Heere, 1572, oil on panel. The National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, on show at Sudeley Castle, Gloucestershire. © Archivart/Alamy

4Coronation Portrait of Elizabeth I by an unknown English artist, c. 1600, oil on panel. National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG5175. © IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

5Portrait of Queen Elizabeth of England playing the Lute by Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1576/80, vellum stuck onto card miniature. Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire. © Bridgeman Images

6The Darnley Portrait by an unknown continental artist, c. 1575, oil on panel. National Portrait Gallery, London. © Eric James/Alamy

7Portrait of Robert Dudley by an unknown Anglo-Netherlandish artist, c. 1575, oil on panel. National Portrait Gallery, London. © World History Archive/Alamy

8The Hampden Portrait by Steven van der Meulen (or George Gower), c. 1563, oil on canvas transferred to panel. Private collection. © CPA Media Pte Ltd/Alamy

9The Sieve Portrait of Elizabeth I by Quentin Metsys II, c. 1583, oil on canvas. Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. © Keith Corrigan/Alamy

10Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I by Nicholas Hilliard, 1595–1600, watercolour on vellum (miniature). Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021

11The Phoenix Portrait by Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1573/75, oil on panel. Tate Britain, on view at National Portrait Gallery, London. © Incamerastock/Alamy

12The Pelican Portrait by Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1573/75, oil on panel. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. © IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

13The Rainbow Portrait by Isaac Oliver (?), c. 1600, oil on canvas. Hatfield House, Hertfordshire. © IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

14Portrait of Sir Francis Walsingham, attributed to John de Critz the Elder, c. 1589, oil on panel. © National Portrait Gallery, London

15Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots in Captivity, after Nicholas Hilliard, inscribed 1578, oil on panel. © National Portrait Gallery, London

16Portrait of William Shakespeare (Chandos Portrait), attributed to John Taylor, 1600/10, oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, London. © Bridgeman Images

17Portrait of Philip Sidney by an unknown artist, c. 1576, oil on panel. National Portrait Gallery, London.© Prisma Archivo/Alamy

18 Bacton Altar Cloth, 16th-century fabric. On loan to Hampton Court Palace, London. © Historic Royal Palaces/Bridgeman Images

19Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I, circle of Nicholas Hilliard, c. 1592, oil on canvas. Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire. © Incamerastock/Alamy T7FWYD

20Portrait of Sir Walter Raleigh by an unknown English artist, 1588, oil on panel. National Portrait Gallery, London. © Photo 12/Alamy

21The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I by an unknown artist (formerly attributed to George Gower), c. 1588/90, oil on panel. Royal Museums, Greenwich. © IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

22The Ditchley Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, c. 1592, oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, London. © Active Museum/Active Art/Alamy

23 Corset of Elizabeth I from effigy. © Leon Neal/Getty Images

24The Ermine Portrait by Nicholas Hilliard or William Segar, c. 1585, oil on panel. Hatfield House, Hertfordshire. © Bridgeman Images

25Elizabeth in procession to Blackfriars in 1600 by Robert Peake the Elder (?) c. 1600/01. Collection of Sherborne Castle, Dorset. © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy

26Queen Elizabeth I in Old Age by an unknown English artist, c. 1610, oil on panel. Private collection, Corsham Court, Wiltshire.

INTRODUCTION

GLORIANA

‘SOME ARE BORN GREAT, SOME ACHIEVE GREATNESS’

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Writers have portrayed the life and reign of Queen Elizabeth I for centuries – in books, plays and films – and the fascination remains today. Easily one of our most popular monarchs, in 2002 she was among the list of ‘10 Greatest Britons’ in a BBC poll. She is admired as a successful leader and a woman ahead of her time who is an integral part of England’s national story. But her early life was full of uncertainties and she was an unlikely candidate to be the greatest offspring of Henry VIII. This daughter, by Anne Boleyn, was the wrong sex in a world governed by men and she was often considered illegitimate because her parents’ marriage was annulled. The odds were stacked against her, but Elizabeth would survive the vicissitudes of her siblings’ reigns, numerous Catholic plots to kill her, the formidable Spanish Armada and the most obvious obstacle of all: her gender.

On becoming Queen, Elizabeth needed a very strong image to unite her country and consolidate her power. Art was a powerful device for displaying royal magnificence and for propaganda but a mere likeness would never be sufficient. Elizabeth’s portraits increasingly relied on glittering jewels, gowns and accessories for the projection of majesty. Along with her formidable grasp of public relations, her persona was a vital ingredient of her rule. The ‘Cult of Gloriana’ developed towards the end of her reign, a movement in which authors, musicians and artists – such as Spenser, Shakespeare, Tallis, Byrd and Hilliard – revered her as a virgin goddess, unlike other women. It was an idea sustained by public spectacle, chivalry, sonnets and oration which paid homage to Elizabeth as a deity. The Queen’s image was widely owned and distributed for the masses, thanks to the expansion of printing and, for the wealthy, through the medium of the painted portrait.

Elizabeth’s England was a small kingdom on the fringes of Europe which grew in self-confidence, in no small part because of the Queen herself. Her long reign provided domestic peace and stability, allowing the arts to flourish so that the Elizabethan era would prove to be a ‘Golden Age’. The eighteenth-century antiquarian Horace Walpole said in his Anecdotes of Painting in England that there ‘was no evidence that she had much taste for painting, but she loved pictures of herself’. Successive periods in history have invested her reign with significance and a large part of this legacy is her captivating image.

ELIZABETH I AND THE THREE GODDESSES

Hans Eworth, 1569, oil on panel, Royal Collection Trust

The allegory referred to in this painting is the Judgement of Paris, a theme derived from Greek mythology which also became popular in Roman art. Three of the most beautiful goddesses, Venus, Juno and Minerva, compete for the prize of a golden apple, dedicated ‘to the fairest’. Jupiter, King of the Gods, was intended to judge the competition, but instead he nominated Paris, Prince of Troy, to carry out the task. Paris chose Venus as the winner on the strength of her promise to help him win the hand of the most beautiful woman alive, Helen, the wife of Menelaus, King of Sparta. (It was Paris’s seduction of Helen and his refusal to return her that led to the Trojan Wars.)

The panel can be visually divided into two sections. To the left-hand side, Elizabeth is emerging as though onto a stage. She enters the scene through a classical archway leading from a substantial brick building. Inside the open door of the structure can be glimpsed a gold coffered ceiling, a frieze containing the Tudor coat of arms and a canopy displaying her own arms. She is wearing a crown and carrying an orb and sceptre, the most powerful attributes of monarchy. Her ladies-in-waiting are deep in conversation and are perhaps unable to see the vision before them. They are superfluous to the allegory, but they serve to ground the Queen in reality. Elizabeth would not have travelled anywhere without her accompanying ladies.

The right side of the picture is allegorical, with the three goddesses presenting a riot of movement and vivid colour. They are set into a pastoral landscape that includes a depiction of Windsor Castle and Venus’s chariot drawn by swans.

As the painting was commissioned either by Elizabeth or as a gift to her, the Queen would have been expected to take centre place in the composition. However, she has been supplanted by Juno, the goddess of marriage and fertility. Juno, Queen of the Gods, is gesturing for Elizabeth to follow. The position of her arm is echoed by the curved neck of the crowned peacock, her sacred bird. But Elizabeth will not be enticed by Juno’s association with matrimony and family life.

In the middle of the three allegorical figures is Minerva, the goddess of battle strategy and wisdom, whose powers include bestowing heroes with courage. She wears a helmet and a breastplate embellished with the head of a gorgon, and she carries a standard. The gorgon, with its hair of venomous snakes, was given to Minerva by Perseus as protection. Anyone looking at a gorgon was turned immediately to stone. In common with Elizabeth, Minerva, the warrior maiden, was believed to remain perpetually a virgin.

On the far right is Venus, the goddess of love, beauty, pleasure and passion. Her discarded smock belongs to the age of Elizabeth rather than a world of myth. Its distinctive and colourful embroidery is typical of Tudor design of this time. The broken arrows on the ground, the bow and the discarded quiver refer to Venus’s son Cupid, who tried in vain to shoot Elizabeth with his darts of love. The implication is that despite her beauty, Elizabeth is impervious to matters of the heart.

The goddesses reflect the choices Elizabeth has made to rule wisely. Juno represents Elizabeth’s rejection of marriage and children, Minerva emphasises her skill, wisdom and courage in battle and Venus alludes to the Queen’s beauty and the life of pleasure that she has rejected, enabling her to govern her nation wisely. And yet, it is Elizabeth who retains the prize – not a golden apple but a golden orb, a powerful symbol of monarchy that represents the Queen’s triumph over all three of these classical goddesses.

Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses is intended to reflect the Queen’s rejection of marriage and children, her courage in battle, her wisdom and her beauty.

The first record of this picture is in 1600, in a diary written by Baron Waldstein, a German nobleman, who had seen it at Whitehall Palace. It was sold for £2 in the Commonwealth sale in 1652 to ‘Hunt and Bass’, of whom little else is known, but it returned to the Royal Collection during the reign of James II. On the frame is written: ‘Pallas [another name for Minerva] was keen of brain, Juno was queen of might, / The rosy face of Venus was in beauty shining bright, / Elizabeth then came, And, overwhelmed, Queen Juno took flight: / Pallas was silenced: Venus blushed for shame.’

The identity of the artist has been disputed. The initials ‘HE’, painted on a rock in the lower right corner, are suggestive of the artist Hans Eworth, although art historian Roy Strong considers the initials were originally ‘HF’ (Hoefnagel fecit) referring to the Flemish painter Joris Hoefnagel, noted for his topographical views and his mythological subjects. The landscape and the painting of Windsor Castle bear similarities to the Hoefnagel picture The Marriage Feast at Bermondsey. At present, the Royal Collection has attributed the painting to Hans Eworth, the artist from Antwerp who is associated with complex allegorical works and with the design of sets and costumes for Elizabeth’s court entertainments.

There are two points of interest unrelated to the meaning of the picture – it is believed to present the earliest pictorial representation of Windsor Castle and it is the only known portrait of Elizabeth wearing gloves. It is the first known allegorical portrait of Elizabeth and, to appreciate the image, viewers needed to interpret the classical messages contained in the painting. Elizabeth is depicted moving forwards from a dark interior into the light of the ‘new learning’ and the Renaissance.

1

ELIZABETH I AND THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE

‘A KINGDOM FOR A STAGE …’

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Elizabeth acceded to the throne of England in 1558 following the death of her half-sister Mary I, and inherited an England that had been divided by bloody religious turmoil. The nation had also suffered defeat in a French war, which had lost Calais and shaken confidence.

Under Elizabeth’s rule, the religious turbulence of the previous reigns grew calmer as the Queen avoided the religious extremism of her siblings and the Protestant Reformation became less contested. England’s centralised government was well organised and efficient. A third of the population still suffered in poverty but for the most part there was an atmosphere of peace and growing prosperity. Overseas ventures opened new trade routes that had a positive effect on the Elizabethan economy. Painting, poetry, theatre, literature and music flourished, supported – as all arts need to be – by the economic growth of the country.

Throughout Elizabeth’s reign, painting continued to be dominated by portraiture, as it had been during the rule of the preceding Tudor monarchs. However, Elizabethan portraiture lies in the period between the death of Holbein (in 1543) and the arrival of Van Dyck (in 1632); it rarely gives us an insight into the true personality of a sitter in the frank manner of the former or the dignified style of the latter. Full of signs and symbols, the chivalric, courtly interpretations by Elizabethan artists often hide from us the face of the living person. Foreign artists, principally those originating from the Netherlands, still monopolised artistic production in England due to their superior painting skills. However, in the genre of miniature painting, English artists began to find distinction not only at home, but also abroad. Elizabeth’s court artist, Nicholas Hilliard, forged an international reputation and was the first English artist to find fame in Europe.

There was no established art market through which artists could sell their works and so, to sustain themselves and their families, they depended on the patronage of prosperous supporters. For reasons of wealth and prestige, the Queen and her courtiers were highly sought-after patrons.

After her father, Henry VIII, Elizabeth is the most familiar to us of the Tudor monarchs, because during her reign the collecting and display of portraits became increasingly popular. It was possible to buy a ready-made portrait of the Queen to display in private homes, universities, guildhalls and town halls. Full-length portraits became popular due to the novelty of a whole person standing in front of you.

The most potent influence on all the arts in England was Elizabeth herself. The young Queen was initially presented as the embodiment of sexual virtue, to defend her from charges of unfitness to rule due to her sex. As she aged and it became clear that she would leave no heir, so the Queen became vulnerable and her realm potentially unstable. Youthful and flattering face patterns of Elizabeth had been employed by artists from around 1575. Soon after 1590 (when the Queen was in her sixties), the artist Nicholas Hilliard invented a smoother-skinned and more exaggeratedly youthful image of her known as a ‘mask of youth’. This did not just improve on the Queen’s image as the face patterns had done, but replaced her true features. From then onwards, she was rarely painted as elderly but as an ageless beauty who represented the eternal nature of monarchy and the magnificence of the nation. Patterns of this mask were distributed to artists to copy, ensuring that the Queen’s public image was always consistent and ever youthful. Submitted to the judgement of her Serjeant Painter, George Gower, any portraits of the Queen produced after around 1596 that did not conform were destroyed. The subterfuge of this ‘Cult of Gloriana’ lasted almost until the Queen’s death in 1603 when she was approaching 70.

To reinforce her timeless image, the Queen’s clothes for portrait sittings required careful consideration and Elizabeth’s women of the Privy Chamber looked after their care. The most notable among these ladies was Blanche Parry, who also managed the Queen’s jewels. An inventory of 1587, compiled by Blanche on her retirement, revealed that Elizabeth had 628 pieces of personal jewellery. Blanche was twenty-five years older than the Queen and had served her for fifty-seven years, forsaking marriage and children to devote herself entirely to her mistress. Her family were from Herefordshire and in 2015 a piece of embroidered fabric was discovered in the Parry family church of St Faith in the small Herefordshire village of Bacton. It had been kept as an altar cloth, but it is believed to have originally come from a dress worn by Elizabeth I. Out of more than 1,900 spectacular dresses that the Queen owned at her death, this is believed to be the only surviving fragment. It was probably given as a gift to Blanche and it appears to have originated from the elaborate gown Elizabeth wore in the Rainbow Portrait. This is the most puzzling painting of Elizabeth ever completed and one that will be discussed in Chapter Six.

The art of embroidery was an important skill for Elizabethan women, children and sometimes men. Church vestments, altar hangings and chasubles (outer vestments worn by a priest when celebrating mass) had been decorated with needlework since medieval times but embroidery was increasingly used for secular purposes during the Tudor period. There was a developing taste for rich, colourful embroidered domestic furnishings and clothing. Almost all young girls were taught how to sew, a talent that was viewed as a mark of their diligence and piety. Elizabethan ‘samplers’ (pieces of material on which the various stitches were practised) can occasionally still be discovered in auctions and antique markets, usually embellished with the date and name of the needleworker. For those of the lower socio-economic classes, sewing and making clothes was a practical skill that could provide an income. For the daughters of the nobility, the ability to produce elaborate and decorative embroidery was an accomplishment that would complement their roles as mistresses of large households.

Elizabeth admired and supported all the arts and she enjoyed both popular entertainment and the higher arts. She attended events such as bear baiting and cock fights as enthusiastically as music recitals or classical plays and poetry readings. Her understanding of poetry and literature was widened by her ability to speak, read and converse in six languages.

The Queen enjoyed music and was an accomplished player of the lute and the virginals. As well as composing music and singing, she danced with grace and expected her courtiers to be able to do the same. New types of musical instruments led to changes in musical composition. An early violin was invented, along with a form of oboe that produced a more complex arrangement of sounds, meaning that Elizabethan music became more expressive and emotional. Sacred music (particularly that with Latin lyrics) evoked Catholicism and during Elizabeth’s Protestant reign it became less frequently performed. And yet the Queen enjoyed church music and appointed Thomas Tallis, who had formerly composed for Mary I, to her Chapel Royal. Tallis had been present at Elizabeth’s coronation and was considered one of England’s greatest composers, best remembered for his choral music. It is an example of Elizabeth’s religious tolerance that he was joined in the Chapel Royal by William Byrd, another Catholic composer. A form of secular music known as the madrigal was invented in Italy, but by the mid-sixteenth century it had largely fallen out of favour in Europe. In Elizabethan England, however, the madrigal was increasingly acclaimed. Byrd popularised the English form of madrigal, a love poem for four to six voices, which he set to music with English lyrics.

All creative artists aspired to the patronage of the Queen or her courtiers and, in many instances, she inspired their plays, poems and music. In his poem ‘The Shepheards Garland, III’, published in 1593, the poet Michael Drayton styles Elizabeth as Beta, ‘the Queene of Muses’.

Perhaps the most ambitious poem written during the reign of Elizabeth I was Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, first published in 1590. It is one of the longest poems in the English language, although it was never completed; his original plan was to write twelve volumes, with each one focussing on a different moral virtue. The books contain two principal characters, a ‘Prince Arthur’, who represents the legendary King Arthur of medieval romance, and the ‘Faerie Queene Gloriana’, symbolising Elizabeth. It is set in a mythical land where the Queen is offered ‘mirrours more than one’ in which she can see herself reflected. In the same work, she is associated with Belphoebe, a virgin huntress personifying the goddess Diana, a reference to Elizabeth’s chastity. Belphoebe falls in love with Timias, so Spenser is encouraging the Queen to fall similarly in love, renounce her virginity and produce an heir. The writer hoped to gain royal favour through his work and the Queen responded by awarding him a lifetime pension of £50 per annum. For comparison, a statute given at Westminster in 1588 lists an employed brewer as earning £10 per annum and a butcher £6. The Masters employing them would have earned a greater salary but Spenser’s pension still appears very generous. It would have afforded him a comfortable lifestyle even without his other commissions.

Thomas Wyatt had introduced the sonnet into England in the early sixteenth century. It originated in thirteenth-century Italy, when Petrarch had perfected it to write about his love for a married woman named Laura. A sonnet is a lyrical poem that is traditionally fourteen lines long. The first eight lines outline the predicament and the following six lines resolve it. Its form was changed in English to comprise three quatrains (a series of four lines) and a two-line rhyming couplet. Sir Philip Sidney, an Elizabethan poet, courtier and soldier, popularised the English sonnet to express unrequited love. He penned 108, but none were published before his early death in battle at the age of 31. In English, these emotive and imaginative pieces were often set to music in the form of a madrigal.

Much of Elizabethan poetry has faded from popular consciousness, but the work of William Shakespeare continues to be widely read and performed to avidly interested audiences, a testament to a writer who composed some of the greatest literature of all time. Shakespeare’s first narrative poem, Venus and Adonis, is an erotic work of more than 1,000 lines, based on a myth from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Shakespeare turned it into a comic poem in which a goddess tries unsuccessfully to seduce an uninterested young man. It was written in 1592 as plague closed the London theatres, denying Shakespeare his usual means of income. In 1594, he published The Rape of Lucrece, taken again from the work of Ovid. These poems were extremely popular and were reprinted many times. Shakespeare continued writing and produced a sequence of 154 sonnets that gained him a reputation as a serious poet and a chronicler of the Elizabethan age.

At the time, authors were restricted in what they could write and how they could express themselves, so plays for the theatre tended to be written in allegory, where they presented contemporary problems and criticised political situations in a disguised form. Prior to 1598, the majority of playhouse plays were written anonymously or with the name of the author disguised for fear of finding themselves in prison or worse. Ben Jonson was arrested and imprisoned for The Isle of Dogs, a play he co-wrote with Thomas Nashe in 1597, although it was suppressed so completely that no copy exists to explain his crime today. Throughout the arts, it was abundantly clear to writers that they were expected to glorify the Queen.

In the field of decorative arts, the demand for silver grew quickly during the reign of Elizabeth. There had been a rapid rise in population and the expanding middle and upper classes sought quality domestic silver to furnish their new and impressive homes. In 1564, the Company of Mines Royal was established to ‘search, dig, roast and melt all manner of ores of gold, silver, copper and quicksilver in the counties of York, Lancaster, Cumberland, Westmoreland, Cornwall, Devon, Gloucester, Worcester and Wales’. The directors of the company included Elizabeth’s chief advisor, William Cecil, Lord Burghley, her favourite Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, politician and courtier. Elizabethan silver is often lavishly decorated with fruit, vegetation and grotesque figures, reflecting the European taste for Renaissance design, but, as the century wore on, decoration became less elaborate. Silver goods were fashioned in London to match the highest European standards and around the country centres, such as Norwich in Norfolk or Exeter in Devon, were producing top-quality pieces of plate. Unlike artists, who did not generally sign their work, silversmiths tended to mark their plate designs with their initials or various marks, including a fish, a sun or a cross.

In 1572, Elizabeth gave away gifts of silver weighing almost 6,000 ounces. It was a popular commodity with a growing market. The wooden and pewter spoons of Henry VIII’s era were now supplanted by those made of silver. As the Elizabethan age progressed, it became fashionable for more varied items to be produced in silver, such as sconces, mirrors, lustres and jars. As these secular items were being fabricated, so ecclesiastical silver was being melted down. Today, few ecclesiastical pieces made prior to the reign of Elizabeth survive.

The Queen’s goldsmith from around 1558 to 1576 was the unusually named Affabel Partridge, a London-based craftsman whose trademark was his exceptional quality and lavish embellishment. When Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558, she commissioned a new Great Seal, the device employed by the Chancery to show that the attached document had been approved by the Queen. When a monarch died, their Great Seal was destroyed. Elizabeth’s half-sister Mary’s seal had been intentionally damaged after her death to render it obsolete and Elizabeth gave it to her new Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, Sir Nicholas Bacon. In the 1570s, Bacon commissioned Partridge to melt down Mary’s seal and use it to make three gilt silver cups, one for each of his three houses in Hertfordshire, Suffolk and Norfolk. Partridge engraved Bacon’s coat of arms on the bowl of the cups, along with a boar – a pun on the name Bacon. The Norfolk cup is in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, acquired with support of the Art Fund in July 2021 from the collection of Sir Ernest Cassel, a British merchant banker. A second cup has resided in the British Museum since being bequeathed in 1915. The whereabouts of the third cup is unknown. Hallmarked in London, they are among the few surviving pieces by Partridge, connected to the Elizabethan court and demonstrating the immense skill of the Queen’s goldsmith.

Elizabethan architecture became a distinctive feature of the English countryside as wealthy courtiers built themselves lavish prodigy houses. In summer, Elizabeth would travel the country on progresses to visit and lodge at these elaborate abodes. As she was accompanied by as many as 500 attendants in her retinue, her stay represented an enormous expense for the host. It was considered a great honour to be selected for a visit by this parsimonious monarch, who built no great houses or palaces herself.

Builders of the time modified the quadrangular medieval layout, omitting one side, resulting in an ‘E’-shaped building that permitted sunlight and air to circulate more freely. The Great Hall on the ground floor was generally where the most expensive art and sculpture was situated and where guests were invited to be impressed. It was now used less than in the time of Henry VIII, with the Long Gallery running above the Hall becoming the centre of Elizabethan entertaining and family living. It was still uncommon, in England, for houses to be designed by architects; usually the owner worked in collaboration with builders and stonemasons. One of the first architects in England was Sir John Thynne, steward to Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, who in 1549 was already designing a great house at Longleat. Thynne employed the master mason and architect Robert Smythson, a designer of manor houses who went on to design Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire and Burghley House in Lincolnshire.

Encouraged by new advances in science, England looked abroad and Elizabethan seafarers explored uncharted areas of the globe. Martin Frobisher landed on Baffin Island, Humphrey Gilbert in Newfoundland and Walter Raleigh was awarded a charter to colonise Virginia. Controversially, Elizabeth backed privateers, such as Francis Drake and John Hawkins, who raided Spanish and Portuguese ships, bringing the gold back to fill English coffers. Henry VIII had founded the Royal Navy but, of his three children, it was Elizabeth who prioritised its strength. It seems fitting, therefore, that during her reign ‘Britannia’, a Minerva-like female warrior, wearing a helmet and holding a trident and shield, should be employed as the female personification of England.

The reign of Elizabeth I was an era of great expansion in all fields of the arts. It was a time of world exploration and of achievements that inspired national pride and embodied a feeling of great optimism. It was also an age of conspiracies and plots against the Queen as she faced continual threats to her life and reign, both religious and political. Her Secretary of State, Sir Francis Walsingham, built up an ongoing network of spies and used his contacts to gather intelligence information from across Europe to ensure the Queen’s safety.

Elizabeth died in 1603 after a reign of almost forty-five years. The sun finally set on Gloriana, as the last Tudor monarch died in her own bedchamber, having taken reluctantly to her bed. As Sir Walter Raleigh said, ‘she was a lady surprised by time’.

2

FAMILY AND SURVIVAL: THE EARLY YEARS

‘SHE HATH A VERY GOOD WIT, AND NOTHING IS GOTTEN OF HER BUT BY GREAT POLICY.’

SIR ROBERT TYRWHITT

The child who would become ‘Gloriana’ was born at Greenwich Palace on 7 September 1533, the daughter of Henry VIII and his charismatic second wife, Anne Boleyn. She was named Elizabeth after both her grandmothers, and her gender was a bitter disappointment. Planned celebrations for Henry’s long-awaited son were cancelled and the letters prepared to announce the birth of the ‘Prince’ were hastily changed by the addition of a scribbled letter ‘s’. The King had broken from the Church of Rome to marry Anne and secure his dynasty with a male heir, who was expected to become a great king in years to come. In an age when the hand of God was seen in everything, this birth was a terrible reversal of fortune. Nobody would have predicted that Henry’s true heir had indeed been born that day in Greenwich and that Anne Boleyn’s daughter would one day reign over an English ‘Golden Age’.