Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

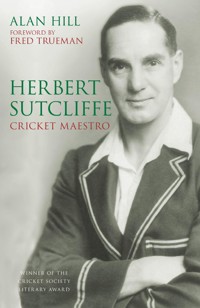

A national hero in his playing days, Herbert Sutcliffe belongs to a select band of all-time cricketing greats. Alan Hill's award-winning biography of the Yorkshire and England batsman charts his extraordinary transformation from cobbler's apprentice to urbane gentleman: one of the coolest, most determined and technically accomplished practitioners the game has ever known. Blessed with the looks of a matinee idol, Sutcliffe was a complex, often enigmatic, personality. As a cricketer, he was touched with genius. His career spanned exactly the years between the wars and he performed with distinction in every one of those seasons. He scored 50,138 first-class runs, including 149 centuries, and his remarkable Test average of 60.73 is the highest for an English batsman – higher than those of Hobbs, Hammond or Hutton. Herbert Sutcliffe: Cricket Maestro calls upon the reminiscences of Bob Wyatt, Sir Donald Bradman, Sir Len Hutton and Les Ames among other illustrious contemporaries, to evoke the splendour of Sutcliffe's achievements for Yorkshire and England, and to bring to life the vivacious story of one of the greatest batsmen ever.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 436

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2012

This paperback edition published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL 50 3 QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Alan Hill, 2012, 2022

The right of Alan Hill to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 18039 9094 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To Betty, for keeping an eye on play in another Yorkshire innings.

Contents

About the Author

Foreword

Introduction

1 An Orphan at Pudsey

2 A Glorious Dynasty

3 A Yorkshire Welcome

4 Holmes and Sutcliffe

5 Alliance with the Master

6 Triumphant in Australia

7 The Aura of Authority

8 Conquerors on a Gluepot

9 The Captaincy Furore

10 Peerless at the Summit

11 555 at Leyton

12 The Imperturbable Maestro

13 The Snare of Bodyline

14 Sutcliffe and Hutton

15 Fanfares in Retirement

Statistical Appendix

Bibliography

About the Author

John Arlott, when reviewing Alan Hill’s biography of Herbert Sutcliffe, voiced his praise of an acclaimed cricket biographer, whose balanced style, he said, ‘constantly leads the reader to think, thus heightening both his concentration and interest.’ Alan Hill has twice won The Cricket Society’s prestigious Literary Award for his biographies of Sutcliffe and Hedley Verity. His other books include studies of Les Ames, Peter May, Jim Laker and the Bedser twins.

Foreword

by Fred Trueman OBE

It is wonderful news that a good and loyal friend of Yorkshire cricket, Alan Hill, has produced another book on our great men of the past. Herbert Sutcliffe’s career presents a story of amazing achievement by a player who was a model example for any young cricketer.

Herbert was a proud man and he had every right to be so. The determined orphan lad had made good and become the revered champion of Yorkshire and England. Anyone who could earn the respect and friendship of people like Bill Bowes and Hedley Verity was entitled to claim that he had given of his best in life as well as cricket. Herbert was always spick and span in appearance and as courageous in his crippled old age as he was as the master batsman against the world’s fastest bowlers. He once told me that there were some players who could play fast bowling and others who couldn’t. ‘But, you know, if everybody told the truth, no one really likes it,’ he said.

Herbert still holds the highest average for an English Test batsman. They say he was a terrible man to get out. He was at his best in a crisis. In his day, batting technique was really put to the test on uncovered wickets. Herbert and his Yorkshire and England opening partners, Percy Holmes and Jack Hobbs, had few, if any, equals on the real ‘stickies’. Alan Hill writes about the heroics of Sutcliffe and Hobbs in those epic struggles against Australia at the Oval and Melbourne in the 1920s. Only two magnificent players could have survived in such conditions. They did and England won.

Herbert was also acknowledged as one of the most unselfish batsmen of his time. He didn’t hog the limelight unless it was necessary for him to shield a lesser player. I doubt whether there were many more loyal cricketers. Brian Sellers owed much to Herbert, as Yorkshire’s senior professional, during our great days in the 1930s. Douglas Jardine also had the good fortune to have Herbert at his side on the bodyline tour. Herbert did not see anything wrong in our tactics, and was unswerving in his support of his captain in a controversial series.

In his retirement, when I got to know him, Herbert was a great encourager of young Yorkshire players, particularly those who had the good sense to listen. I did listen to him. He watched me as an eighteen-year-old and said I would play for England. In a way, rather like Herbert’s prophecy about Len Hutton when he was a young boy, his praise raised expectations about my ability in Yorkshire. It was a bit of a millstone. But Herbert didn’t scatter compliments like confetti. He knew his cricket and cricketers. Herbert also thought I had potential as a batsman. I did score nearly 10,000 runs, including three centuries. But when you are bowling around 1,000 overs a season, as I did, it isn’t easy to put more spadework in as a batsman. I could graft when necessary, but I didn’t always play as straight as Herbert would have liked.

Herbert became a close friend and my wife and I entertained him at our North Yorkshire home. I think he found it a peaceful retreat after the harsh atmosphere of at least one of his nursing homes. He did surprise us one morning. It was about 10.30 and Veronica brought out the coffee. ‘Good Lord, haven’t you got anything stronger?’ he asked. His old eyes twinkled when Veronica suggested that he might like a gin and french. ‘Yes, that would be better,’ he said. It was his favourite tipple. And he needed it. Herbert was a strong man but he was in constant pain with his arthritis. I reckon he deserved his gin.

Many people, as Alan Hill relates, have said that Herbert was a severely practical performer. He had to cut out the frills as an opening batsman. He had to lay the foundations for the dashers. Herbert had the ideal temperament for this job. He was a magnificent judge of line and length. But it would be wrong to suppose that he was a slowcoach. He could hit sixes with the best of them. Herbert once hit Ken Fames and the rest of the Essex bowlers all over Scarborough. He went from 100 to 194 in forty minutes.

Maurice Leyland could wield the long handle pretty well himself. He was batting with Herbert at Scarborough. I once asked Maurice how many he scored during the onslaught. Maurice said: ‘Sixteen. I only had four balls – that’s all Herbert left me – and I hit each one of them for four.’ Maurice wasn’t often left standing as a batsman. Anyone who could do that must have been one hell of a player.

Introduction

Pride can so often be confused with pomposity. In his thrusting ambition, Herbert Sutcliffe could not escape the darts of envy, even among his own folk at Pudsey. The orphan boy, in his sporting odyssey, was blessed with a vision and resolution to rise above his humble origins. He was equipped by nature to live above the average. From his earliest years he displayed a dignity and earnestness which drew him into the embrace of influential benefactors.

Countless cricket chronicles have misleadingly fostered the haughty image, which was, in reality, a reflection of his unabashed self-confidence. It did induce a reverential awe, and for some, including his Yorkshire and England successor, Leonard Hutton, led to a view of Sutcliffe as a slightly forbidding figure. Yet his actions, fully expressed for the first time in my book, belie this portrayal. Sutcliffe was, as many people have pointed out, the reverse of the egotist. He was unselfish and loyal as a cricketer and unfailingly courteous as a man. Along with his great England batting partner, Jack Hobbs, Sutcliffe was committed to advancing the cause of the professional cricketer. ‘Our profession as a respected one started with Jack and Herbert. They gave us a new status,’ said Stuart Surridge, the former Surrey captain and a close business associate and friend of the Sutcliffe family.

In the 1930s Sutcliffe, as the senior professional, became a father figure to a host of aspiring young Yorkshire professionals. He was given the title of the ‘maestro’ in the Yorkshire dressing room. Bill Bowes and Hedley Verity, two illustrious colleagues in a glorious decade, were devoted to Sutcliffe. They regarded him as a kindly mentor and respected his insistence on a strict code of cricket conduct and meticulous appearance. Ellis Robinson, the Yorkshire off-spinner and one of the new guard before the war, remembered his senior’s calmness in the most difficult of circumstances, both on and off the field. ‘He set a perfect example to we who got into the Yorkshire team,’ said Robinson. ‘One of his great attributes, which many failed to appreciate, was, for want of a better word, his guts. Many times I have seen him black and blue, taking the brunt of the bowling on his body, rather than play the ball and thus resisting the chances of getting out.’

Exploring the riches of Herbert Sutcliffe’s career has been a challenging and rewarding task. He was a cricketer who deserved to be admired almost without reservation. His indomitable spirit as the mainstay of Yorkshire and England shone brightly in the memories of those who stood alongside him. He is remembered for his imperturbable temperament. The late Les Ames said that Sutcliffe would go first into his side mainly because of the Yorkshireman’s unruffled approach and tremendous belief in himself. In Australia, the scene of many of Sutcliffe’s greatest triumphs, Sir Donald Bradman and Bill O’Reilly both paid tribute to the qualities of an unyielding and combative cricketer. ‘He was virtually unshakeable,’ said O’Reilly. ‘You could leave him for dead with a ball and he’d almost leer at you.’

A legion of collaborators have enabled me to retrace the steps in a fascinating trail winding over eighty years. In placing on record the caring father and magisterial family man I am greatly indebted to the support of Bill and John Sutcliffe and their sister, Mrs Barbara Wilcock. They have provided many character insights and much valuable illustration material. For my impressions of Sutcliffe’s early years in the Nidderdale village of Summerbridge and the sketch of his father, Willie, I am pleased to acknowledge the assistance of Barry Gill, the secretary of the Dacre Banks Cricket Club. At Pudsey, where Sutcliffe moved while still a young boy, I have found diligent supporters. Ralph Middlebrook was my friendly guide on an important research visit to the town. Mr Middlebrook enlisted the much appreciated aid of Roland Parker, Richard Smith, Ruth Strong and Mrs M. Tordoff, of the Pudsey Civic Society, to immeasurably strengthen my portrait. They, along with Mr J.W. Varley and Dr Sidney Hainsworth, both lifelong friends of Sutcliffe, have provided intriguing recollections of a hitherto largely uncharted period leading up to, and including, his service with the Yorkshire Regiment in the First World War. There have been many expressions of Sutcliffe’s humanity and tributes to his gracious character. A telling example was his enduring friendship with John Witherington, one of his most devoted admirers. I am extremely grateful to Herbert Witherington, of Whitburn, Sunderland, for allowing me to quote from the long-running correspondence with his brother.

My thanks are also due to Tempus and their enterprising sports publishers for reissuing my award-winning biography. They have ended a long wait for those who missed the original edition published sixteen years ago. I am pleased that others will now have the opportunity to rejoice in a cricket gladiator who matched the Australians on their own ruthless terms and came out best.

I must also acknowledge the courtesy and help of Mr Stephen Green, the MCC curator at Lord’s; Mr Ross Peacock, assistant librarian of the Melbourne Cricket Club; and the British Newspaper Library staff at Colindale, London. I have delved happily and profitably into the writings of A.W. Pullin (‘Old Ebor’) and J.M. Kilburn in the Yorkshire Post. Other allies on the Yorkshire scene have included Ron Burnet, Raymond Clegg, Michael Crawford, Capt. J.D.W. Bailey, Robin Feather, J.R. Stanley Raper, Ted Lester, Tony Woodhouse, John Featherstone, F.G. Jeavans, Mick Pope and Tom Naylor. My good friend, the late Don Rowan, was a constant rallying force during the course of a marathon project. Testimonies to Sutcliffe’s greatness as a cricketer and a man have come from people in many walks of life. A small army of collaborators have provided a rich brew of anecdotes to be stirred by this biographer. They include Lord Home of Hirsel, Tom Pearce, Freddie Brown, Tommy Mitchell, Arthur Jepson, John Langridge, Len Creed, David Frith, Cyril Walters, Max Jaffa, Philip Snow, Rex Alston, H.M. Garland-Wells and Stuart Surridge. Doug Insole, Wilf Wooller and Peter May have also offered their observations on Sutcliffe as a Test selector in the late 1950s.

In my assessment of the epic achievements of Sutcliffe’s career, I drew hugely on the wisdom of Bob Wyatt, a shrewd, perceptive and kindly collaborator. As always on my visits to his home in Cornwall, I found pleasure in his hospitality and the buoyancy of a remarkable man. I was also privileged, in the last years of their lives, to gain a rapport with Les Ames and Sir Leonard Hutton. With their passing, cricket lost two notable elder statesmen and my conversations with them illuminated my understanding and added to my appreciation of an illustrious cricketer.

Finally, it is opportune to refer to the obituary tribute of Ellis Robinson, who cherished his association with Herbert Sutcliffe. ‘To those of you who never saw Herbert play, you missed some unforgettable and majestic hook shots off the world’s fastest bowlers. I treasure the fact that I had the good fortune to have played alongside Herbert and been his colleague and friend.’

Alan Hill

Lindfield, Sussex

June 2007

1

An Orphan at Pudsey

‘Herbert was involved with fine people and because he was good at cricket they wanted to help him.’

Roland Parker, the former PudseySt Lawrence club captain

The brass band boomed vigorously, discharging its volleys of sound among the excited, swaying people. Behind the marching musicians followed a torchlight procession of Yorkshire villagers, each one caught up in the delirium of a momentous September day. Held aloft by the rejoicing cricketers, above the forest of torches, was a gleaming goblet-shaped cup, donated by the gentry of the Nidderdale district.

Willie Sutcliffe, his life soon to be cruelly terminated, was one of the celebrants on this day in 1894. The last train had steamed into the valley and he alighted to be borne, along with the rest of his victorious teammates, on a joyful promenade. Dacre Banks had defeated local rivals Glasshouses by 122 runs at nearby Birstwith to win the Nidderdale League Challenge trophy. Throughout the night, the elegant cup was filled to the brim, time and time again, for all wanted to toast the champions.

Presiding at the presentation ceremony at Birstwith in the afternoon was the Revd Alexander Scott, the vicar of Pateley Bridge. He had missed the opening stages of the title decider in order to fulfil a long-standing engagement to officiate at the marriage of two young friends at Wakefield. As he told the cricketers afterwards, he was so keen to attend the match that he was actually out of the church and into a cab, and on his way to the railway station, before the bridal party left. He arrived at the Birstwith ground to join a capacity crowd of 900 spectators. A quick glance at the scoreboard told him why the Glasshouses contingent were in a jubilant mood.

Dacre Banks, after winning the toss, were toiling against a confident attack. Willie Sutcliffe was bowled in the first over. His captain and fellow opener, George Brooks, soon followed him to the pavilion. The Holmes brothers, Jack and Richard, ‘trundled so well,’ reported the Nidderdale Observer, that four wickets went down for 27 runs. The decline was halted by Robinson and Gill, who ‘obtained a complete mastery of the bowling and took the score to 92 before another wicket fell’. Gill reached his half-century as the bowlers wavered. The report considered that ‘the excitement must have been too much for them, as not one of them could find a good pitch and came in for punishment’. The Dacre Banks’ tail wagged merrily and Ellis, coming in tenth man, ‘commenced to hit out brilliantly, landing a ball from Richard Holmes clean out of the field for six.’ Ellis moved briskly to an undefeated 33, scored in under half an hour.

The opening alarms were forgotten in the late flurry of runs. Dacre Banks totalled 179. Sutcliffe, eager to restore his pride after the batting lapse, took four wickets in a spell of sustained aggression. Only two of the Glasshouses batsmen reached double figures. Their gloom was matched by the lowering clouds. The match was abandoned in the failing light. At 57 for eight wickets, Glasshouses were probably beyond recovery, but their decision to surrender their claims to the cup and try again another day provided an unsatisfactory climax to the game.

The celebrations in Nidderdale were but a prelude to an event of greater significance for Yorkshire and England. Two months later, on 24 November, at their cottage home in Gabblegate, Summerbridge, Willie Sutcliffe and his wife, Jane Elizabeth, announced the birth of their second son, Herbert. Herbert’s later allegiance to Pudsey, where he moved while still a baby, along with his elder brother, Arthur, is not in dispute, but the good people of Nidderdale cherish their association with a great cricketer. The Sutcliffe family home still stands in a cluster of cottages in the renamed East View facing on to the Pateley Bridge–Harrogate road.

Herbert’s father, Willie, had fine credentials as a cricketer and a man. ‘A more kindly disposed gentleman never went into a cricket field and it was wished that Dacre had more like him,’ was the verdict of one contemporary. In Nidderdale he was referred to as ‘above average in local cricket’. As a medium-pace bowler, he was noted for his accuracy, and it was said of him that he could hit unguarded stumps four times out of six. He obviously possessed considerable potential because he attended trials at the Yorkshire nets at the same time as George Hirst. Willie Sutcliffe, in one unconfirmed account, worked at a local sawmill at Dacre Banks. His employer was a Peter Wilkinson, who, as president of the local club, offered Sutcliffe the appealing proposition of a job to persuade him to play cricket at Dacre Banks. In those days of modest fixture lists, Sutcliffe was able to share his cricket services between Dacre Banks and Pudsey St Lawrence, after the move across the moors to the West Riding township. At Pudsey he assisted his father, the publican at the King’s Arms. His brothers, Arthur and Tom, also played for the St Lawrence club.

Nidderdale triumph: Willie Sutcliffe, Herbert’s father (pictured first left in front row) was a member of the Dacre Banks XI which won the Nidderdale League Cup in 1894. (J.B. Gill)

The Sutcliffe boys, Herbert and Arthur – and their new baby brother, Bob – were plunged into grief when their father died in the summer of 1898. Willie Sutcliffe was a rugby centre three-quarter as well as a cricketer. He had suffered a severe internal injury while playing rugby in the previous winter. The injury, diagnosed as a twisted bowel, was aggravated in a cricket match. He died within a few days. He was aged thirty-four.

Willie’s widow, Jane, and her bereaved family returned to Nidderdale. The elder boys, later to be joined by Bob, were enrolled at Darley School, about three miles from their former home at Summerbridge. Herbert’s iron temperament, and his ambition to rise above his origins, was probably forged during this unhappy time. He and his brothers had to watch their mother in the throes of consumption as she battled bravely to fend for her young sons. By the time she remarried Tom Waller, a clogger master in the boot trade at Darley, the illness had taken a distressing hold on her life. She was allowed only a short term of happiness. Jane is also believed by the Sutcliffe family to have become pregnant with another child. It was this burden, on top of her already poor health, which led to her death, at the age of thirty-seven, in January 1904.

Whether, as has been said, Tom Waller was illiterate and considered unsuitable to raise his stepsons is a matter for conjecture. The fortunes of Herbert Sutcliffe might have taken a different course had Waller been entrusted with his upbringing. Entries in the Darley School register reveal that Herbert and his younger brother, Bob, left the school to resume their formal education at Pudsey some time before their mother’s death. The elder Arthur was reunited with his brothers afterwards. A decision had clearly been taken, probably at the instigation of ‘three remarkable ladies’ back in Pudsey, as to the future custody of the children.

Rallying to the rescue of the orphaned boys were Willie Sutcliffe’s sisters, Sarah, Carrie and Harriet, who ran a bakery and confectioners in Robin Lane, Pudsey. Carrie, as the middle aunt in age, became Herbert’s guardian, and Arthur and Bob found equally caring foster mothers in Sarah and Harriet. From the aunts, all devoted Congregational churchgoers, the boys learned the disciplines of religion. Herbert, in fact, was unswerving in his devotions throughout his life; he was a Sunday school teacher as a young man; and his cricketing star first flickered in church teams at the turn of the century. ‘Herbert was involved with fine people and because he was good at cricket they wanted to help him,’ commented one Pudsey townsman.

The Sutcliffe boys were ushered into a kindly but strict household in Robin Lane. In addition to the aunts, Arthur Sutcliffe (‘Uncle Arthur’), a cricket stalwart of the Pudsey St Lawrence club, was there to keep a fatherly eye on them. The boys slept in a loft above the bakehouse, and they had to make a nightly ascent by ladder to go to bed. Barbara Wilcock, Herbert’s daughter, wincingly provided a memory of a Sunday ritual of her childhood. ‘Herbert used to take us [Barbara and her brother, Bill] to a freezingly cold church to attend long services. Afterwards, we went to see Aunt Harriet, who would be cooking the Sunday joint on the kitchen range. She would cut off titbits for Bill and myself.’ They were then allowed to enter the austere parlour, a dubious privilege because it was reserved for Sundays; a fire had only just been lit and it was as cold as the church.

Herbert Sutcliffe described how his real craze for cricket began at the age of eight (this would be soon after his return to Pudsey and can be counted a new dawn in his life in a sporting as well as a domestic sense). From this time onwards, his great ambition was to play for the St Lawrence club where his uncles, Arthur and Tom, along with his father, Willie, had played. He had first to blink back the tears when he was rejected by the Congregational Church club. ‘Nay, lad, you’re too small; come back when you’re bigger,’ he was told by the club officials when he asked to be allowed to practise at the Long Close ground. As he regularly attended the church, the refusal was, to say the least, uncharitable; but the undaunted Herbert was more hospitably treated by the neighbouring Stanningley Wesleyans. When Stanningley heard about the rebuff they lost no time in inviting him to join their team. Herbert was overjoyed and always remembered their kindness to him in later years. In his boyhood, Herbert was looked upon as more of a bowler than a batsman; and in one notable display in the 1907 season he took all ten wickets in a match.

Herbert’s enthusiasm and promise brought a coveted promotion in 1908 when he was called up to play for the Pudsey St Lawrence second team. He had been spotted by Richard Ingham, his first sporting benefactor and the St Lawrence captain, while playing in a Pudsey workshops competition on the Britannia ground. Ingham, the exemplar of the self-made man, was at this time a dignitary of considerable local standing and head of a worsted spinning business at Pudsey. He was born in the Sandy Lane district of Bradford, one of a family of twelve children. At the age of ten, he was a half-timer in a local mill. After his apprenticeship, he was the manager of a company in Malmo, Sweden before returning home to go into business on his own account at Crawshaw Mills, Pudsey.

Ingham was also a highly respected local cricketer. He had spent five seasons at Eccleshill in the Airedale League before moving to Otley. At Eccleshill, one of his colleagues was Albert Cordingley, a slow left-arm bowler, who at the turn of the century had vied for a place in the Yorkshire team with Wilfred Rhodes. Lord Hawke, in fact, had advocated Cordingley as the stronger candidate before Rhodes demonstrated his credentials. At Otley, Ingham was captain when the club beat Farsley by three runs at Yeadon to become the Airedale League champions in 1904. Business commitments brought Ingham to Pudsey in the following year. It was the start of an outstanding career with the St Lawrence club. He was captain from 1908 to 1919 and president of the club from 1920 until his death in 1935. Ingham, as a cricket all-rounder, demonstrated the astuteness which marked his success as a businessman. ‘As a leader Dick is ideal,’ was the verdict of a Pudsey contemporary, when Ingham came to live and work in the town. ‘His natural Yorkshire shrewdness comes to his assistance in the captaincy of the St Lawrence team.’

Ingham served on the Pudsey town council for twenty-one years and was elected mayor in 1922/23. He was also a member of the Yorkshire County Cricket Club committee and chairman of the Bradford Park Avenue football club. During his long term in the council chamber he was amusingly described as having the ‘practical man’s distrust of oratorical thrills… he has a Yorkshire pungency which brings the dreamer back to earth with distressing acuteness.’

On his scouting mission in 1908, Richard Ingham had noted and marked the poise of the young Herbert Sutcliffe in the workshops league match. He had watched, with growing attention, the efforts of the rapidly disillusioned bowlers. At first, as a gesture of kindness, they had sent down a sequence of encouraging lobs to the boy. Herbert was not impressed and treated the gentle deliveries with disdain. The bowlers soon realised that their generosity was unwarranted; but they had allowed Herbert his chance. They did not get him out until he had scored 70. Cricket was always a serious business for the aspiring Sutcliffe. He was diligent and zealous in the nets. The memories of the Pudsey seniors laid stress on Herbert’s keenness. ‘While the other team members, having completed their ten minutes in the nets, would gather in groups and chat,’ said one man, ‘Herbert bowled and fielded as if a match were in session and every run counted.’ Herbert himself considered that his attitude at practice helped him to build up his concentration. A photograph from this time shows the young Herbert, immaculate and composed, in a St Lawrence team group. He faces the camera with a stare of pride. The older men appear almost like courtiers in his presence.

Herbert’s cottage birthplace at Gabblegate (now renamed East View) which faces on to the Pateley Bridge-Harrogate road. (John Featherstone)

One of Herbert’s early appearances for the St Lawrence Club was reported in the Pudsey and Stanningley News. The match was against the Stanningley and Farsley Britannia Second XI in September 1908. The newspaper commented:

Pudsey St Lawrence’s second string had to fight hard against Stanningley and Farsley in the latter part of the game, their last wicket partnership being a very stubborn one. Every praise is due to little Sutcliffe (the son of that well-known local cricketer, the late Willie Sutcliffe). He is really a wonderful good length bowler for his age. He was also top scorer with 27, and it was somewhat singular that the next best scorer, with 16, should be Will Armitage, a colleague of young Sutcliffe’s father in his palmier days.

Herbert was still only fourteen when he made his first-team debut for St Lawrence midway through the following season. In the Saints’ ranks before the First World War were Henry Hutton, father of Leonard Hutton, and Major Booth, the Yorkshire cricketer. Herbert thought that St Lawrence must have been a man short for the derby match against the seniors of Stanningley and Farsley. He was lucky enough to be given the vacant place:

Anyway, I went, a terrified little figure [the phrase strikes an odd note for someone of his fortitude], wearing white shorts, into the field while our opponents rattled up a useful score. Then, when their innings was over, I waited about the pavilion watching the St Lawrence wickets fall regularly and, I am afraid, rather cheaply. I was not happy about it at all, but when my turn came – I batted at no. 6 – I was ready for the job. The feel of the bat gave me a comfort though I cannot remember whose bat it was. I am certain it was not my own. For forty-five minutes that borrowed bat stayed in my hands, and though I scored no more than one run with it, I brought it out unbeaten when time came, and the match was saved.

In 1911, Herbert switched his allegiance to the rival Britannia club where, he said, ‘my batting improved by leaps and bounds’. He finished the season with an average of 33.30. The decision to make the move was largely prompted by an offer of clerical employment by Ernest Walker, the Britannia captain and a textile mill owner at Pudsey. There was also the question of insufficient time for practice, a weighty matter for Herbert. He had left school at thirteen and was then serving an apprenticeship in the boot and shoe trade as a ‘clicker’ (fastening boot soles to uppers) with the firm of Salter and Salter in the Lowtown area of the town.

The apprenticeship ended abruptly during a busy time at the Pudsey factory. The priorities of cricket training meant that Herbert kept missing overtime work. Charles Salter, the owner, reprimanded his young employee, and told him that he must make up his mind whether he wanted to be a boot craftsman or a cricketer. Herbert was upset by the incident and worried about the reaction of his Aunt Carrie, of whom he was very fond. His anxiety was quickly allayed. ‘Come and work for me,’ said Ernest Walker, ‘I’ll double your wage and let you play cricket.’ Roland Parker, a future St Lawrence captain, in relating this story, said: ‘They all knew this boy [Herbert] because he was so obviously a star of the future.’ In later years, Herbert referred to the immense debt he owed to Ernest Walker. ‘There are leaders in every sphere of life who, by their example, personality, demeanour and character, make a big impression on young people. Ernest was the incarnation of the best in sportsmen – one of the best who ever lived.’ Walker was an extremely good club cricketer and close to county standard. He and the young Sutcliffe would later share some fruitful opening partnerships for Britannia. Herbert’s work at the Walker mill office also had other beneficial effects. It fostered an interest in book-keeping, which served him well in his later business career.

Herbert was doubly fortunate in winning the approval of two influential mentors. First, Richard Ingham, and then Ernest Walker had shrewdly recognised his potential. In 1911, Walker was more than pleased to bring Herbert into the Britannia fold. The mysterious element is that Ingham, with first call on Herbert’s services, did not find a job for the youngster at his mill. Roland Parker recalled that Ingham and Walker were boon companions: ‘By signing Herbert Ernest really stole a march on his friend.’ In an interesting sequel, Herbert, perhaps a little rueful at his earlier defection to the rival cricket camp, did return to the St Lawrence club for one season in 1916.

Sutcliffe’s rapidly blossoming talents as a batsman at Pudsey were brought to the notice of the Yorkshire cricket authorities at Headingley. In April 1912, he was invited to attend the county practices. Herbert remembered his apprehension and wildly fluctuating thoughts about his prospects. The indecision was soon quelled. The surety of purpose, which governed all his actions, prevailed. He was resolved to make a bid for county status.

‘The fateful day of the Yorkshire practice arrived,’ recalled Herbert. ‘I must admit a certain amount of nervousness was inwardly felt on entering the ground.’ He changed and wandered into the nets. George Hirst, the benevolent guide of this and later Yorkshire cricket generations, welcomed him with a beaming smile. ‘I’ve heard a lot about you. Don’t be nervous, just make yourself at home. You ought to be at home because we’re all cricketers here. Play your own game and you’ll be quite all right,’ was his greeting as Herbert fumblingly buckled on his pads. ‘All my nervousness vanished the moment I stepped into the net,’ said Herbert. ‘I was on my mettle from the start and set my teeth to fight hard.’ The trial was a success and a few days later Herbert was invited to play for a Colts XVI against the county team. ‘My luck in this match completely deserted me, for I was out in quick time in each innings for under double figures,’ recalled Herbert. The failure provoked a discouraging response from one well-meaning friend. He compounded Herbert’s disappointment with the words: ‘All right in the nets, you know, Herbert, but short of temperament for the middle.’ The adviser believed that frayed nerves would prove Herbert’s undoing at county level. ‘Stick to your job and enjoy club cricket,’ he said. The criticism did not go unheeded, except that it had the opposite effect of bolstering Herbert’s resolve.

At Headingley, where Herbert came under the exemplary control of George Hirst and Steve Doughty, the Yorkshire second-team coach, there was a strict emphasis on the importance of pad play. The adherence to this second line of defence was to prove an important discipline. Herbert said he never regretted the time he sacrificed while being taught to play with his legs. ‘The swing and swerve ball had been developed so much that almost every team had experts who were able to do practically anything with the ball in the air and it was absolutely impossible for anybody to enter first-class cricket with the idea of playing with the bat alone.’

Herbert’s early attempts to deploy the pad strategy did leave him worried and bemused. On his return to Pudsey club cricket, he was dismissed lbw on three successive Saturdays without scoring. Ernest Walker, as his club captain, was also puzzled by the lack of form. Walker registered a protest to Steve Doughty. ‘What are you doing to young Sutcliffe?’ he asked. ‘He can’t get a run for us since he joined your lot at Headingley.’

Boy with a future: Herbert (centre, front row) as a fourteen-year-old in the Pudsey St Lawrence team. On his right is Henry Hutton, father of Leonard Hutton. Richard Ingham, the club captain (fourth from right, back row) and Major Booth, the Yorkshire and England all-rounder (far right) are also feature in the photograph. (Richard Smith)

Herbert did master this crucial phase in his cricket apprenticeship. It strengthened his defence to spread dismay among bowlers and it gave him extra confidence in attack. There were two learning seasons in 1912 and 1913 when his batting averages suffered as he digested the lessons of Hirst and Doughty. For a man who never surrendered his wicket gladly, it must have been galling to fail in executing new strokes.

By the summer of 1914, with war on the horizon, he had built up his armoury as a cricketer. At the age of nineteen, he unveiled his mastery in the Bradford League. The Bradford Cricket Argus described two innings of 54 and 76, in which he was undefeated, as ‘first-rate expositions’. In June, Herbert was selected to represent the Bradford League against the Yorkshire Second XI at Park Avenue, Bradford. The county colts were pushed hard to gain victory by one wicket in an exciting match. Herbert hit 73, out of 179, in the League’s second innings. ‘As an exhibition of batting, the best performance was that of Sutcliffe,’ reported the Cricket Argus. ‘He batted with supreme confidence and good style against bowling of quite the best Second XI class. He went in at the fall of the third wicket, when only 33 runs had been scored, and was last man out after batting for two hours.’ Sutcliffe’s innings included two sixes and eight fours and was ‘unmarred by a single chance’.

Sutcliffe was also associated with a future Yorkshire colleague, Emmott Robinson, in the county Second XI which twice beat their Surrey counterparts at Rotherham and the Oval in 1914. At Rotherham, the match was dominated by Robinson, who struck an unbeaten 172, and Barnsley bowler A.C. Williams, who took 12 wickets in the match. Yorkshire were the victors by an innings and 18 runs. Robinson augmented his run proceeds with two half-centuries for the county seconds in the seven wickets’ success over a Huddersfield and District XI at Fartown. Sutcliffe’s contributions were smaller but the Yorkshire Post noted the ‘punishing power of his on-driving’ and added: ‘he is possessed of a good physique and should develop into a fine player.’

Sutcliffe moved up to open the Yorkshire colts’ batting for the first time against an East Riding XI at Beverley in August. The selectors were rewarded with a second-innings half-century. ‘He was confident and stylish in this two-hour innings, his best performance for the second eleven,’ commented the Cricket Argus. ‘In Sutcliffe Yorkshire have a capable right-hand batsman, with youth on his side. In his movements in the field he looks every inch a cricketer, and possessing as he does a variety of good strokes, it would seem to be a sound policy to persevere with him.’ The report cannily balances praise and caution in its commendation. Yorkshire players, not excluding the great Wilfred Rhodes, had to satisfy vigilant juries. The examinations were searching and there was no danger of swollen heads among even the most gifted of White Rose apprentices.

Back home in Pudsey, the enthusiasm for Sutcliffe was less restrained. Herbert’s batting feats were relished as much as the Sunday dinner roast. His most ardent and loyal admirers were in the little Yorkshire township. One of them, Fred Ambler, a future mayor of Pudsey, lived opposite the Britannia ground. Ambler was a faithful valet in Herbert’s early years. He carried his idol’s long brown cricket bag and whitened Herbert’s boots for a shilling a week.

Ernest Walker and Sutcliffe were Britannia’s opening partners in the last cricket summer before the war. Their alliance obeyed the precepts of care, but a sense of purpose was always evident in their batting. It was demonstrated with a special fervour in one match against the old rivals, Stanningley and Farsley Britannia. The Pudsey and Stanningley News reported:

Walker and Sutcliffe at once proceeded to give a pretty exhibition of batting. Sutcliffe gave a very hard chance off the first ball he received, but the two batsmen played steadily against good bowling. They were not parted until the score had reached 86 when Walker, who had just posted his half-century, was caught and bowled by Barnes. Sutcliffe also completed his 50; he was joined by Nettleton, and these two took their team to victory.

As proof of his increasing consistency, Herbert hit a stylish 82 for Britannia in the nine wickets’ victory over Tong Park, and this was closely followed by half-centuries against Queensbury, Undercliffe and Baildon Green. It was his best season in club cricket. Herbert was fully entitled to say that he had a ‘real royal time’ in Bradford League and Yorkshire Second XI cricket in 1914. His aggregate in all matches for the year was 1,278 runs; in nine innings for the Yorkshire Colts he scored 249 runs (average 35.57); and in 21 innings for Pudsey Britannia his tally was 727 at an average of 45.44. Ernest Walker, second in the club averages, totalled 365 runs, and only three other Britannia batsmen, Nettleton, Burton and Tordoff, exceeded 200 during the season. Herbert was unapproachable in the Bradford League as well. He overtook the previous record league aggregate of 693, established by Cecil Tyson at Tong Park.

Sutcliffe’s association with Jack Hobbs was still an unregarded prospect. But it was fitting that his future England partner should join the galaxy of talents in wartime league cricket in Yorkshire, and surpass the record with Idle two years later. Hobbs’s achievement was to be dwarfed by his shared conquests with Sutcliffe in other greater arenas. The record flourish in Yorkshire linked their names for the first time.

2

A Glorious Dynasty

‘“How many has he got?” was a question which did not require an answer in Pudsey. In the old days it meant “John” later “Major”, and then “Our ’Erbert”.’

Yorkshire Post

The lofty greystone town which became Herbert Sutcliffe’s adopted home, and to which he clung with affection for almost seventy years, stands on tiptoe in cricket renown. Pudsey glows with a sporting lustre, bright and strong enough to pierce the gloom of the smoking mill chimneys at the beginning of the century. This homely parish, now enveloped by its big city neighbours, Leeds and Bradford, glories in a tradition with few parallels.

It has fostered a remarkable dynasty of Yorkshire cricketers. The first was the steadfast John Tunnicliffe (Long John O’ Pudsey), who shared a notable opening partnership with Jack Brown from Driffield. Tunnicliffe, a product of the Britannia club, was born on 26 August 1866. At sixteen, he was debarred from becoming a member of the club because of a rule which limited the youthfulness of candidates to eighteen. A special general meeting was called to amend the rule and open the door to the tall, gangling boy, who, even at that age, was one of the biggest hitters in the district. In 1891, playing for the Yorkshire Colts at Sheffield, Tunnicliffe drove a ball over the pavilion and into the back of a brewery yard on the other side of the road.

Such spectacular strikes did not always carry the field. Tunnicliffe was judged a rash young cricketer. So persistently did he commit batting suicide that he was deemed incorrigible. In 1892, his second season with Yorkshire, he was quietly omitted from the team. It was thought that he had little chance of regaining his place. He was, however, given another opportunity to redeem his previous failures, when he was included in the team which played Lancashire in the August bank holiday match at Old Trafford. His turn to bat came on the Tuesday afternoon. Lancashire had scored 471 on a good wicket. Yorkshire, on a wicket freshened by heavy rain in the early morning, were struggling against Briggs, Mold and Alec Watson. There was a vast crowd, all very pleased at the discomfort of the Yorkshire batsmen, and the bowlers were in full cry.

It was not exactly the time in which a batsman would choose to play for his existence as a county cricketer. Tunnicliffe had learned his lesson. He was grimly resistant and the Lancashire bowlers could not dislodge him. At the end of the innings he was 32 not out. In the follow-on, Lord Hawke was sufficiently impressed by Tunnicliffe’s tenacity to send him in first. The result was that the Pudsey man obtained a splendid half-century, by far the highest score, and secured his position in the team, never to lose it again. Tunnicliffe had discreetly schooled himself in defence, with the happiest of consequences. He took on the mantle of a sheet anchor batsman, a role which had never been adequately filled since the days of Louis Hall.

Tunnicliffe had, though, to wait until 1896 before he began his association with Jack Brown. The story of their subsequent record partnership against Derbyshire will be told later; but these two men were Yorkshire’s pilots in 26 century first-wicket stands. Two of them, a telling feat at the time, were obtained in one match against Middlesex at Lord’s in 1897. In the first innings they scored 139, and in the second, without being separated, they hit 146 to bring about a Yorkshire victory. Tunnicliffe and Brown, as is the case with all prominent opening alliances, could each prop up one end while the other attacked. Brown, in his later years of indifferent health, often preferred patient methods to his more characteristic brilliancy. Tunnicliffe would then show that the powers of his hitting had not declined. A writer in the Cricket Magazine commented:

His great reach enables him to get well over the ball, which he watches closely, and he has a very strong defence. He perhaps hardly possesses a sufficient variety of strokes to be judged among the greatest of batsmen, but his driving power is tremendous, while, in consequence of his height, more half-volleys come his way than to a batsman of fewer inches.

It was often said of Tunnicliffe that he was worth his place in the Yorkshire team for his slip fielding alone. In Yorkshire, they said that catches hung on to him like hats on a hatrack. He took 694 catches to earn comparison with Woolley, Hammond and John Langridge in this position. He was also a more than competent emergency wicketkeeper. Not all his catches were taken at slip. In the outfield he had a safe pair of hands when Jessop or other big hitters were on the rampage. Tunnicliffe only gradually established himself as a regular slip fieldsman. Once there, this Gulliver of a man, at 6ft 3ins, pulled off some astonishing catches. ‘Whether from a smart cut off Hirst’s expresses, or an incautious peck at Rhodes’s “breakaways”, how many a batsman has turned round to see the giant arm fully extended with the ball tightly held above the head, or maybe an inch or so from the grass,’ commented W.A. Bettesworth in 1903.

Many tales were told about Tunnicliffe’s spectacular catches. Two Yorkshiremen were overheard discussing his agility. One of them said:

I tell you I once saw Jessop start to make a hit to long leg, but at the last moment he suddenly altered his mind, as he often does, and made a sharp late cut.

Now Long John, as soon as he saw Jessop going to hit to leg, started for that side, because there was nobody at long leg. Just as he had moved he saw what Jessop was up to and tried to stop himself, with the result that he turned a complete somersault. But it is a fact that in falling over John remembered his duties and stretched out his long arm just in time to grasp the ball at slip.

His companion listened thoughtfully to this account. After a short pause he remarked casually:

That’s nowt. I remember that he and David Hunter [the Yorkshire wicketkeeper] once nearly had a scrap over a catch of his. It was in this way. He was fielding at short slip to Peel, very close in, and the last two men were battin’, with three runs to make to win. ‘Tunny’ got a bit excited, and when one of the batters just touched the ball he copped it before it had time to reach Hunter.

Of course, Hunter was in a rage. He said it was infringing on his prerogatives. Lord Hawke had to make peace between them.

In seventeen seasons with Yorkshire, Tunnicliffe scored over 20,000 runs, including 1,000 runs in a season twelve times. After his retirement, he was the coach at Clifton College and later a member of the Gloucestershire county club committee.

Yorkshire’s next recruit from Pudsey in 1908 was the illstarred Major Booth, who received his grooming at the St Lawrence club in Tofts Road. Booth was the son of a prosperous local grocer and attended Fulneck School managed by the Moravian religious sect at the foot of the town. Booth and Alonzo Drake, who died of heart disease in 1919, were the rising stars before the First World War, and were confidently expected to spearhead the county’s attack into the 1920s. Booth was one of Pudsey’s favourite sporting sons during a sadly curtailed career. He was the first of the town’s international cricketers, representing England in two Tests in South Africa in the 1913/14 series. His selection was acknowledged at a dinner attended by fellow Yorkshire cricketers George Hirst, David Denton, Roy Kilner and Wilfred Rhodes at the Queen’s Hall, Pudsey at the end of the summer. He received the gift of a solid silver cup bearing the inscription: ‘Presented to Major W. Booth by members of the Pudsey St Lawrence Cricket Club and friends in appreciation of the eminent position attained by him in the world of cricket.’ George Hirst, as expansively friendly as ever, told the assembly: ‘If your Major is successful in South Africa they should be pleased; if not, they should make excuses for him.’ Booth was unable to live up to the expectations of his Yorkshire admirers in South Africa. But there were mitigating circumstances. On the Sunday before the first Test at Durban he was involved in a motor accident, thrown out of a car as it hit a bank approaching level crossing. He escaped with a minor back injury.

Booth, tall, good-looking and charming, was on the threshold of greatness at the outbreak of war. As a second lieutenant in the Yorkshire Regiment, he died leading his men into action on the battlefield of the Somme in July 1916. He was aged twenty-nine. There were many good judges who contended that his death deprived England of a fast bowler who might have restrained the havoc of Warwick Armstrong’s Australians in 1921. In his brief career, Booth demonstrated that he could have become one of the great allrounders. He scored nearly 5,000 runs, twice achieving 1,000 in a season, and took 603 wickets at an average of 19.82. As a right-arm medium-pace bowler, who occasionally deployed a formidable offbreak, he was flatteringly compared to the great S.F. Barnes. Wisden, which named him as one of its Five Cricketers of the Year in 1914, commented upon his bewilderingly late outswingers. ‘He makes the ball swerve away at the very last moment. There is, too, something puzzling about his flight, and if the wicket is doing anything he can make the ball pop up very nastily.’

Long John O’ Pudsey: Tunnicliffe, predatory slip fieldsman, sheet anchor opening batsman and the first of a remarkable cricket dynasty. (MCC)

Booth claimed two hat-tricks, bowling unchanged with Drake in two matches in 1914; he took over 100 wickets in three successive seasons – 1912-1914 – and three wickets in four balls three times. In 1912, against Middlesex, he had match figures of eight wickets for 136 and scored 107 not out. In 1913, his best season, he recorded a double of 1,228 runs and 181 wickets. Yorkshire had good reason to mourn the loss of both Booth and Drake. Their rich promise can be gauged from some of their last performances together. In 1914, they bowled unchanged against Gloucestershire, Booth taking 12 wickets and Drake eight, the first time this feat had been accomplished since Hirst and Haigh in 1910. Drake then proceeded to make cricket history in taking all 10 wickets against Somerset, finishing with match figures of 15 for 51. In this triumphant finale the all-rounders flourished mightily. Booth and Drake shared 313 wickets, and each scored more than 800 runs.