Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Nazi Germany, June 1943, Buchenwald concentration camp. The last place you'd expect to find any form of justice. And yet justice against the SS men who brutalised the prisoners here would be attempted by the unlikeliest of sources – SS officer Konrad Morgen. Nazi Germany, despite the atrocities it carried out on an industrial scale, still had legislation and a legal system, and Morgen used these laws to bring individual members of the SS to justice for their crimes. He was a fearless investigating judge and police official, and when he crossed swords with more powerful forces inside the SS, he was demoted and sent by Heinrich Himmler himself to the Eastern Front as an ordinary soldier in the Waffen SS. But Morgen's skills were still required and he returned to launch a series of criminal investigations in various concentration camps, including Buchenwald. As a direct result of his work, two concentration camp commandants were shot before the end of the war and he arrested three others. Targets of his investigations included Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the Holocaust, and Rudolf Höss, the infamous commandant of Auschwitz. Described by historian John Toland as 'the man who did the most to hinder the atrocities in the East', Konrad Morgen pursued Nazi Germany's worst murderers from inside the SS. This is his incredible true story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 418

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

When you get a cat to catch the mice in your kitchen, you can’t expect it to ignore the rats in the cellar.

Bernie Gunther in Philip Kerr’sMarch Violetsvi

Contents

A Note About SS Ranks

The SS (short for Schutzstaffel, translated as ‘protection squad’) had their own system of ranks and titles. In this book, I have used the nearest equivalent British Army rank to give a general idea of the level of responsibility that each member of the SS had. For example, an SS-Sturmmann (literally ‘storm man’) was near the bottom of the organisation, roughly equivalent to a lance corporal. An SS-Hauptsturmführer (literally ‘head storm leader’) was roughly equivalent to a captain. Konrad Morgen finished his SS career as a Sturmbannführer, a ‘storm unit leader’, which was roughly equivalent to a major.

The SS rank for a general started at SS-Gruppenführer (literally ‘group leader’) and had several additional levels, for example SS-Obergruppenführer (‘upper group leader’). In the British Army, these are equivalent to major generals, lieutenant generals and full generals. Because many of the officers described here moved through the various ranks of general at different times, I have simply described these officers as generals in the narrative in order to keep things straightforward. x

Introduction

MONDAY 25 OCTOBER 1971

Three people are together in a room in Frankfurt, West Germany. John Toland, an American historian, is working on a biography of Adolf Hitler and has come to Frankfurt to meet Konrad Morgen, currently a lawyer. Also in the room is Inge Gehrich, an interpreter.

Toland isn’t interested in Morgen because he’s a successful Frankfurt lawyer. He has come here today because of the surprising and little-known fact that Konrad Morgen, a former SS investigating judge and Reich police official, carried out the very first successful criminal investigation of a concentration camp commandant and he did it not after, but during, the Second World War.

The tape recording of the conversation is not a good-quality one and it’s difficult at times to hear what Konrad Morgen is saying.1 Sometimes I have to rely on Inge Gehrich’s English translation and even then, I am often rewinding the tape and turning the volume up to the maximum in order to make out what is being said. Sometimes a car or truck roars past, and at one stage the telephone rings and a dog barks. 2

Although the quality of the recording is poor, I pay particular attention because it is the only occasion on tape when Konrad Morgen is being conversational. The recordings of his witness testimony at Nuremberg after the war and then again in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial in 1964 are very formal. Even his interview for the TV series The World at War is much more structured than the conversation I am listening to right now.

It is immediately clear that Morgen has a very good understanding of English; several times he is so keen to get his point across that he speaks directly to Toland in English. Although his English is very good, I think I know why he prefers to speak in German and that’s because he’s a lawyer who has been in a lot of courtrooms and he wishes to express himself exactly as he wants to on tape, with no possibility of misunderstanding.

Toland asks Morgen about being an SS judge and police investigator. Is it true that SS courts sentenced concentration camp commandants to death for atrocities against inmates? Yes, replies Morgen, who goes on to say that he personally arrested Karl-Otto Koch, the commandant of Buchenwald, and his wife and then went on to investigate Rudolf Höss, the commandant of Auschwitz. Toland says he plans to write a chapter about this and that most people in the West wouldn’t believe it.

Morgen tells Toland that the higher-up SS leaders didn’t like him and he was dismissed from his job in Kraków. Toland tells Morgen that he’s surprised that the Allies didn’t honour him for the things he did – after all, he risked his life. Morgen sounds embarrassed and simply mutters Ja. Toland adds that it says something about German law that people like Konrad Morgen were able to carry on a legal process. And why not, says Morgen animatedly. 3After all, the government may have changed but the judges didn’t turn into criminals!

Toland wants to know how many other judges were like Morgen? He tells Morgen, ‘You sound like an original to me.’ Ninety-nine per cent of judges were like him, says Morgen. Yes, but how many were acting like Morgen, Toland wants to know. Were these other judges also bringing up embarrassing cases? They wanted to, yes, says Morgen. But he had a special investigative talent, he had the right nose to be a detective. Plus, says Morgen, he was interested in international law. You were a bloodhound, says Toland. Morgen is delighted and says yes, yes! He was called a Blutrichter, literally a ‘blood judge’.

Morgen tells Toland that when he investigated the crimes in Buchenwald, he had been instructed not to investigate political cases. But here he was with a political case. So he investigated on his own initiative, what he calls auf eigener Faust – literally with his own fists. And when he told the senior SS officers about what was going on at Buchenwald, they wouldn’t take action and kept passing him on to the next person. He went to Arthur Nebe (head of the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt or Reich Central Police Detective Office) first, but Nebe said go to Ernst Kaltenbrunner (head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt or the Reich Security Main Office).* Kaltenbrunner said take it straight to Himmler.

At this point in the conversation, Morgen switches to English as Gehrich, the interpreter, hasn’t heard of Nebe and he is impatient to carry on with his story. Morgen wrote to Himmler, who didn’t cover 4it up and, he says, he raised hell. Himmler told Morgen to arrest Koch and told him he would also get the authority to clean up the whole place. Koch was indicted, sentenced to death and executed. But Morgen couldn’t obtain enough proof to get his wife sentenced and she was still under arrest at the end of the war.

Toland asks Morgen, is it true that lampshades were being made of human skin or is that baloney? Morgen says it was other people who found this out. The Americans threatened to kill him if he didn’t testify that Frau Koch had done it but he wouldn’t as he had found no evidence. Toland asks if he was treated well by the Americans. Morgen tells him that they threatened to hand him over to the Czechs, Poles or French if he refused to testify. Toland expresses his dismay at this.

Morgen says that after the war lots of people asked him why didn’t he go after Hitler? In the same way that a US Army judge couldn’t go after President Nixon, or after Kennedy for Vietnam, he couldn’t prosecute Hitler. A judge in the army always reports to the army chief of staff.

The conversation turns to concentration camps and Toland asks Morgen what he thinks of the figure of 6 million Jews who were killed during the Holocaust. Morgen answers simply ‘yes, it’s correct’ in a tone which conveys the meaning ‘yes, of course it’s correct’. Later on, the discussion moves through various senior Nazis to Martin Bormann, head of the Nazi Party Chancellery and Hitler’s private secretary. Earlier in the interview, Morgen had mentioned that he had been imprisoned in Oberursel and Nuremberg by the Americans after the war and had talked to many fellow prisoners about Hitler.

Morgen tells Toland that Bormann never left Hitler’s side. He 5always carried a notebook and whatever Hitler said, he wrote down and turned into an order. Toland is interested in this and asks Morgen if he thinks that this was how the order for the extermination of the Jews came about? Was Hitler thinking aloud and then Bormann wrote it down and turned it into an order? Morgen says the extermination of the Jews was always Hitler’s intention; it was premeditated and carefully managed. Bormann’s role was to facilitate this and make sure that it happened.

Toland asks Morgen where he thinks the order to exterminate the Jews came from. Was it from Hitler? Toland says that many people have told him that Hitler knew nothing about it. Morgen doesn’t agree. He says yes, it came from Hitler. What about Himmler’s role? Morgen says that Himmler was central to the extermination of the Jews.

Toland tells Morgen how grateful he is that he confirmed the killing of 6 million Jews, as he was on the verge of doubting it but now he’s met Morgen and Morgen is the best witness he has come across. It’s clear from this that other interviewees from inside the SS and Nazi Party whom Toland has talked to for his book have rejected this figure.

At the end of the interview, Morgen says he would be glad to read Toland’s book and Toland promises to send Morgen a copy before it’s published in appreciation. When the book is published in 1976, Toland describes Konrad Morgen as ‘the man who did the most to hinder the atrocities in the East’ and describes his work as ‘one man house-cleaning’ as well as a ‘lonesome attempt to end the Final Solution’.2

* * *

6The more I read about and listen to Konrad Morgen, the more I am reminded of Bernie Gunther, Philip Kerr’s fictional Second World War Berlin detective. Like Gunther, Morgen worked for Nebe in the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt, the Central Police Detective Office of the Reich. Like Gunther, Morgen had a career investigating crime during the war and uncovering terrible truths in Nazi Germany, where darkness touched everyone and everything. But while Bernie Gunther was investigating general crimes, Morgen’s particular beat was rooting out criminals in the ranks of the SS, including the Gestapo and the police.

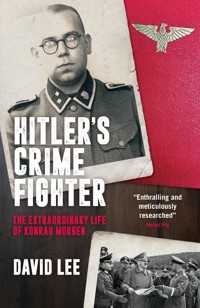

Both Gunther and Morgen faced the same problem: how do you stay alive in the Third Reich and perhaps even prosper without selling your soul to the devil? It was a difficult dilemma for any German and a very acute one for Bernie Gunther and Konrad Morgen. But while Kerr could ensure that the fictional Bernie Gunther always lived to return another day, for Konrad Morgen there were no such guarantees. He was on his own. The title of this book, Hitler’s Crime Fighter, captures the contradiction of an SS investigating judge and police official investigating and prosecuting murder and crime in the Third Reich, which gave itself the legal powers to kill people, especially Jews, and take their money, valuables and property on a massive scale.

While Gunther is a cynical Berlin detective with a large dose of English humour from his creator, Morgen embodied very traditional German values. He had a very strong sense of honour and he was very loyal to his fiancée, Maria, with whom he exchanged constant letters through and after the war, when he was imprisoned by the Americans. He later married her.

Both Gunther and Morgen had a senior Nazi who interfered 7in their lives and sent them off in new directions. While Gunther was often called in by Reinhard Heydrich – head of the Reich Security Main Office before Kaltenbrunner – to investigate crimes, Morgen’s activities were watched over by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler himself. Morgen’s problem was that he worked for arguably the world’s most frightening and dangerous employer and he didn’t play by their rules.

In the first half of the war, Morgen blotted his copybook by investigating SS officers for corruption without fear or favour. These SS officers used their connections to complain to Himmler, who contemplated sending him to a concentration camp. In the end, he decided instead to reduce him in rank and dispatched him to the Waffen SS Division Wiking (pronounced ‘Viking’) on the Eastern Front to fight the Soviet Army in winter.

And then in a plot twist worthy of any Bernie Gunther novel, Himmler changed his mind. Having decided that he needed Morgen’s skills as a bloodhound after all, he recalled Morgen from the front, restored his previous rank as an officer and sent him to investigate the increasing problem of corruption in concentration camps. Going way beyond his brief, Morgen then charged multiple concentration camp commandants, officers and guards with murder.

His approach depended on a literal interpretation of the law in Nazi Germany. Contrary to popular perception, the law and the legal process were very important in the Third Reich – so much so that there wasn’t just one set of laws but two. These were first characterised by Ernst Fraenkel, a German lawyer and political scientist who left Germany in 1938 and wrote a book in 1941 about the twin legal systems in Nazi Germany called The Dual State to reflect these two legal systems operating at the same time. 8

In his book, Fraenkel identifies first what he calls the ‘normative state’, which he describes as ‘an administrative body endowed with elaborate powers for safeguarding the legal order as expressed in statutes, decisions of the courts and activities of the administrative agencies’.3 In other words, Nazi Germany still had a normal legal system similar to those which could be found in most Western democracies at the time.

But then Fraenkel also identifies what he called the ‘prerogative state’, which he describes as ‘that governmental system which exercises unlimited arbitrariness and violence unchecked by any legal guarantees’.4 In other words, in Nazi Germany there was a second parallel legal system, which allowed Hitler and other senior Nazis acting with Hitler’s authority to decide on courses of action that were deemed as legal and which could not be challenged in the courts. The decisions taken as part of this second legal system had terrible consequences for the millions of people who were killed, especially the Jews. In his interrogation after the war by the Americans, Morgen summed this dual legal system up neatly. He told his interrogator, Fred Rodell:

Law in the National Socialist state was several things; as previously, it embodied legal norms and included common law but what was new were the orders from the Führer. In the National Socialist state the Führer united all power in his person; he was the head of state, the chief lawgiver and the chief judge.5

Alongside these two legal systems in the Third Reich, there was an extensive bureaucracy. This meant that every single killing – whether 9an execution for murder as part of normal state processes or the killing of someone or groups of people because of an order from Hitler or from another senior officer acting on his behalf – had to be accompanied by the right paperwork. Any killing which was not a result of normative legal processes or not directly ordered by Hitler or someone acting on his behalf was therefore illegal and could be investigated as murder.

For Morgen, this represented the way to bring criminals in the SS to justice, particularly for murders which had been committed with no lawful order authorising them. Officially his job was to investigate corruption in the SS, and Morgen used this as a way to disrupt the work of the SS and as a way to investigate SS officers for murder. In a way, he was copying what the FBI did when it went after Al Capone. The FBI couldn’t get evidence for murder, so it prosecuted Capone for tax evasion in order to get him sentenced and imprisoned.

As a prosecution witness in the 1963–5 Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, Morgen set out his approach to the court:

I saw a way of proceeding. Where the highest legal principle, life itself, is worth nothing and is trampled into the dirt and destroyed, then all other legal principles, whether they be around property, loyalty or something else, must also collapse and lose their value. And therefore – and I had already convinced myself of this – these people, to whom these tasks had been assigned, were set on a path to criminality. And my instructions and the criminal code gave me my duty to prosecute these crimes, namely crimes which were not covered by official orders. And that’s exactly what I did.610

Morgen was an important witness to events in the concentration camps. But even with his energy and determination, he could not visit all the camps that the Nazis set up. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum there were around 44,000 camps and ghettos, although the exact number will never be known.7

Concentration camps were places where people who were seen as enemies of the state were imprisoned. They were also places where targeted killings of individuals and small groups were carried out and they were places where prisoners were forced to work. Concentration camps also had numerous sub-camps – for example, Buchenwald had at least eighty-eight satellite camps, which were run from Buchenwald itself.8

There were also a number of dedicated extermination camps or killing centres, whose purpose was to kill people, particularly Jews, who were sent there. These were located in Nazi-occupied Poland and included Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, Chełmno, Sobibor, Belzec and Treblinka. It is also worth noting that there were three concentration camps at Auschwitz: Auschwitz I, Auschwitz II (Birkenau, the killing centre) and Auschwitz III (Monowitz).

Morgen’s wartime career in the SS came to define both his career and his life. After the war he was detained by the Americans for over three years, interrogated extensively and used as a witness in the Nuremberg trials. Even after they were completed and he was released, he was summoned back to various courts to give evidence. By the end of the war, Morgen had conducted 800 investigations into crimes committed by members of the SS, with 200 brought to trial. He personally arrested five concentration camp commanding officers and two were executed after their trials.911

He described himself as a Gerechtigkeitsfanatiker, a fanatic for justice, and the list of people he went after is a roll call of some of the very worst killers, thieves and sadists in the ranks of the SS.

This is his story. 12

* I have translated Reichskriminalpolizeiamt as Reich Central Police Detective Office. Other translations use Reich Central Crime Office. The Kriminalpolizei (Kripo) in a German police department is the equivalent of the CID in the UK.

Chapter 1

Beginnings

THURSDAY 6 NOVEMBER 1941

For Walter Krämer and Karl Peix, two concentration camp inmates at Goslar, a sub-camp of Buchenwald, the last day of their lives started like any other. The daily routine was nine hours of work, every day from Monday to Saturday each week. Most of the work carried out by prisoners at Goslar was manual labour at the Luftwaffe base, with some prisoners being sent to work at the mine near the village of Hahndorf.

Most of the prisoners were Poles, Russian political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses, so-called career criminals and what were termed ‘asocial’ prisoners from the Reich.1 What was unusual about Krämer and Peix was that they had been transferred from the main camp at Buchenwald and they were being used for manual labour at Goslar even though both were skilled in nursing and medicine.

Krämer and Peix were both communists and had served as members of the regional parliament. Krämer had been arrested after the Reichstag fire in 1933, which the Nazis had used to target communists. Following a prison sentence lasting until 1936, he was taken 14into preventative custody by the Gestapo and sent to Buchenwald, having refused to spy for them.2 In Buchenwald, Krämer, a locksmith by profession, transformed himself into a nurse and medical practitioner and Peix became his deputy. Together they set about helping their fellow prisoners, and they gained such a positive reputation that even the SS camp personnel came to them for help, preferring to use them rather than their own SS doctors.3

One prisoner, Yaakov Silberstein, testified after the war that Krämer had crawled into the Buchenwald ‘small camp’ at night where Jewish prisoners were held in order to give him medicine for typhus. Krämer also brought another prisoner, seventeen-year-old Artur Radvansky, from the small camp into the ‘big camp’ where political prisoners were held and operated on him, without anaesthetic, for gangrene due to frostbite. He treated him again for an infection after a flogging. For these acts, Walter Krämer was added to the Yad Vashem list of Righteous Among the Nations, which honours non-Jews who risked their lives to help Jews during the Holocaust.4

Alongside their fellow prisoners, Krämer and Peix had also treated camp commandant SS Colonel Karl-Otto Koch for syphilis.5 They had also treated local SS General Prince Josias of Waldeck for a furunculosis infection after the prince had sought treatment on a visit to Buchenwald as part of his official responsibilities as the head of the SS and police in the local area.6 This made their transfer to carry out manual labour at Goslar all the more puzzling. Why would the SS at Buchenwald deprive the main camp of two skilled nurses and medics?

General Waldeck had been taking a close interest in Buchenwald concentration camp since he had had SS Colonel Koch arrested 15on suspicion of corruption the previous year. However, this arrest had not been successful. SS General Oswald Pohl, who ran the SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungshauptamt, the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office in Berlin where he was in charge of all the concentration camps, and SS General Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Reich Security Main Office, complained to Himmler. Himmler then ordered Koch’s release and sent out a general order, which became known as the ‘lex Waldeck’, saying that a commandant of a concentration camp could only be arrested on the direct orders of Himmler himself.

However, General Waldeck could still make life difficult for Koch and he still visited Buchenwald on a regular basis. On one of his visits, he decided to order the release of the two prisoners, Walter Krämer and Karl Peix. However, unbeknown to Waldeck, instead of releasing the prisoners, Koch ordered them to be transferred to Goslar. The next thing Waldeck heard about the two prisoners was that on 6 November 1941 they had both been shot in the back of the head while trying to escape.

According to the official report, both prisoners had died in exactly the same way. Each had suddenly stopped work and made a run for the perimeter. The guards, including SS Sergeant Johann Blank, had in both cases shouted twice as warnings and then fired at the fleeing prisoners. A telegram was sent immediately from Goslar to Buchenwald and to the SS Court in Kassel. The Buchenwald adjutant, SS Lieutenant Heinz Büngeler, was dispatched to investigate. He drove straight to Goslar, where the bodies were still lying where they had been shot.

Before the bodies were moved, the scene was photographed. A post-mortem was carried out to determine the cause of death and 16the SS doctor certified that both had been shot from behind at a distance of 30 metres. The officer in charge at Goslar also filed a report stating that the guards were reliable SS soldiers and listing the previous convictions of the prisoners. The conclusion of the investigation by Büngeler was that both men had been shot while trying to escape.7

General Waldeck did not believe this report. He knew that one of the prisoners had severely inflamed knees, was overweight and could only walk with a limp. And he knew that Büngeler knew this too, as he had known both men from the camp hospital. Plus, why would prisoners who were going to be released try to escape? He referred the case to the SS Court in Kassel, which summoned the guards, the officer in charge on the day and the adjutant in charge of the investigation to Kassel, where they were interrogated under oath. The guard who shot Krämer and Peix stuck to his story: ‘I yelled at the prisoners but they didn’t stop. I had to use my rifle,’ he told the court.8 Faced with this testimony, it appeared that there was nothing more that Waldeck could do.

Eighteen months later, in 1943, Konrad Morgen arrived in Buchenwald and broke the case wide open. He had been sent there to investigate corruption but, as part of his wider investigations, the killings of Krämer and Peix caught his attention. He soon gained a reputation among the SS at Buchenwald and prisoner Stefan Heymann remembered how ‘Morgen was extraordinarily feared and hated by all SS officers in Buchenwald’.9 When Morgen looked at the case files for Krämer and Peix, they were so well put together that he said, ‘Not even the most conscientious or most thorough judge or criminal investigator could have found the slightest trace of any criminal act in those files.’10 However, for Morgen, his experience 17as an SS investigator meant that when he saw reports of prisoners attempting to escape, accompanied by apparently thorough investigations, his suspicions were immediately aroused.

To gather the evidence which would confirm his suspicions that the prisoners had in fact been murdered, Morgen relied on information from other prisoners. But they were initially suspicious of Morgen’s investigations. Alfred Miller, a journalist who had been sent to Buchenwald and who helped Morgen with a number of murders inside Buchenwald itself, found it hard to trust Morgen at the start:

At first I couldn’t make up my mind to tell [him] everything and it took me a long time to start trusting [him] … I was given a document from Prince Waldeck saying that nothing would happen to me and that no one was allowed to harm me. But I said that wasn’t enough. Then Prince Waldeck came along in person and said that if I gave a statement which could be verified then he would personally lobby the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler for my release. So I decided to give a statement.

Miller was eventually released on 13 March 1944 after Morgen intervened with the Reich Security Main Office. ‘I owe my freedom to Dr Morgen,’ he said.11

The truth about the killing of Krämer and Peix was entirely as Morgen had expected. Koch and SS Sergeant Blank had drawn up the plan to murder them and put it into effect. The SS guards on duty were sworn to secrecy, especially when it came to any court-authorised investigation, and they were informed that what they were asked to do was a direct order from Himmler himself. They 18were briefed extensively about what they should say to the investigation, namely, ‘Yes, we shot them because I considered it to be the right course of action. I know of no order which protects the lives of the prisoners.’12

The first part of the plan was to transfer Krämer and Peix to Goslar well in advance of the date Koch and Blank planned to kill them. On the appointed day, Blank made sure that no other prisoners were around in the area where the prisoners were to be shot. Each prisoner was given instructions to fetch water from a well and, suspecting nothing, picked up a bucket and walked to the well. The guards, including Blank, then fired the fatal shots at a distance of 30 metres, removed the bucket from the murder scene and reported it.

Why had they been killed? In his official report, Morgen speculated that Krämer and Peix had known that Koch was stealing donations that richer prisoners at Buchenwald had been making to the camp hospital.13 After the war, Morgen pointed to the fact that Koch was suffering from syphilis and he had been treated by Krämer. To ensure that word of this did not get out, he arranged to have the two prisoners killed.14 Morgen was outraged: ‘They behaved just like gangsters, from the camp leadership right down to the lowest man.’15

Morgen uncovered many unlawful killings like those of Walter Krämer and Karl Peix at Buchenwald. Their murders were included on the final indictment against Koch. Blank hanged himself when he was arrested.16 However, their murders were of great interest to another trial, one which took place after the war in 1947 in Dachau, where the Americans put SS General Prince Josias of Waldeck on trial for the crimes committed at Buchenwald, especially those committed at the end of the war. Waldeck was convicted and sentenced 19to life imprisonment but released due to ill health in 1950 and died in 1967.17

At this trial, Morgen appeared as a witness for the defence. But before asking Morgen details about the murders of Krämer and Peix, the defence lawyer, Dr Emil Aheimer, asked Morgen about his past. He was particularly interested in the times when Morgen had incurred the wrath of the Nazi Party and had fallen out with colleagues in cases where he was sitting with other judges.

One of the judges in the trial asked Aheimer what he was trying to prove by asking Konrad Morgen these questions? Was he trying to prove the credibility of his own witness? Aheimer replied:

No, I want to show the following, the witness, as will be shown, was appointed investigating officer in the complex of questions concerning Koch and what is to be shown here is that the man who was selected for this job was not a man who always did what the SS and the Party always desired him to do. This should serve to demonstrate that the investigation was conducted in a very serious manner indeed.18

This was also a theme of other post-war trials where Morgen testified. Before giving his testimony, there were always questions about how he came to be an SS investigating judge. However, the most detailed questions of all were put to him as part of his interrogation by the Americans after he surrendered to them at the end of the war. And these questions started at the very beginning.

EARLY LIFE

Georg Konrad Morgen was born on 8 June 1909 in Frankfurt, 20where he also went to school, studied and returned to after the war for the rest of his life. After he left school in 1929, Morgen worked at the S&H Goldschmied bank in Frankfurt for six months as a trainee before leaving to study law. He was always very proud of the fact that his studies had a very international flavour – having been a school exchange student in France in 1926, he studied law at universities in Frankfurt, Rome, Berlin, The Hague and Kiel between 1930 and 1933.19

Morgen’s interest in international relations led him to join the Pan European Union as a student. This was an organisation which was founded in 1923 and which wanted a politically, economically and militarily united Europe. When Hitler came to power he abolished the German Pan European Union, as he saw it as a dangerous opponent.

Morgen was also a member of the German People’s Party, a right-wing liberal party which supported the interests of business and industry. In 1931, he went to hear Hitler speak but came away disappointed – his main impression was that Hitler only talked about himself and had no concrete ideas about how to improve things.20 But this did not stop him joining the Nazi Party in 1933 as an ordinary member.

The push to join the Nazi Party came from Morgen’s mother, Anna. She had been very impressed by the flags, the speeches, the singing and the marching, and she believed that Hitler was responsible for a great turning point, especially in terms of reducing unemployment. Morgen himself knew people who had been unemployed for five, six or seven years. She told him, ‘You won’t get a job if you want to work for the government. We made so many sacrifices for your studies.’ Morgen thought to himself, ‘Well, it’s just a formality’ 21and joined up.21 On the other hand, his father, a train driver whom Morgen described as a calm, modest man without any ambition, was, if anything, critical of the Nazis. He just wanted a quiet life as a state railway employee.22

In the same year that Konrad Morgen joined the Nazi Party, he also joined the SS. But this was an involuntary membership. In order to take the law exams, students were required to play sport for two terms beforehand and to do this, Morgen had joined an organisation called Das Reichskuratorium für Jugendertüchtigung or the Reich Committee for Youth Fitness. Then one day, instructors from the SA and the SS appeared and the training started to become more militaristic, with various uniform items handed out for the students. Eventually, the instructors simply divided the students into two groups. One group were told they now belonged to the SA and Morgen’s group were informed that they now belonged to the SS.23

The SA – Sturmabteilung, translated as ‘storm unit’ or ‘storm troops’ – was originally set up after the First World War as a group of men who would provide security at Nazi meetings, which usually meant attacking anyone causing trouble. The SA evolved into an organisation that, alongside putting up posters, beating up opponents and marching up and down, also became a serious military force in its own right.

The SS – Schutzstaffel or ‘protection squad’ – had been set up by Hitler as a unit of personal bodyguards. It then expanded its remit to include protecting other big-name Nazis. In 1929, when Hitler appointed Himmler to head up the SS in the post of Reichsführer-SS, the number of SS personnel was given by the in-house SS magazine as exactly 270.24 Himmler slowly built up the SS with the 22‘right’ sort of people, which included aristocrats like Prince Josias of Waldeck, who had joined the SS in 1930 and become Himmler’s adjutant before being promoted to full SS general by the end of the war.25 Another key appointment was that of Reinhard Heydrich to head up the new SS intelligence service, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), in 1931.

In 1931, Himmler also set up the SS Rasse- und Siedlungsamt, the Race and Settlement Office, under Richard Walther Darré, an Argentinian German who had spent some of his school years at King’s College School in Wimbledon, London. Darré impressed Himmler with his ideas, which revolved around the need to solve the agricultural problems facing Germany in the early 1930s by improving the ‘racial purity’ of the German peasantry. His ideas included settlement schemes in the countryside, raising the birthrate and stopping the rural population drift to the towns and cities.

Himmler also introduced new marriage rules for the members of the SS in 1931. The purpose was to ensure that SS men were racially ‘pure’ and that their future wives were going to continue this racial purity when they had children. To this end, all members of the SS had to apply to the Reichsführer-SS via the Race and Settlement Office for permission to marry. This measure did not go down well both inside and outside the SS, and every year the SS expelled men for marrying without permission. This marriage rule would later cause problems for Morgen and his fiancée, Maria Wachter.

One effect of this new rule was that it set the SS apart from other organisations in Nazi Germany, especially from the SA. According to Himmler’s biographer, Peter Longerich, the SA saw themselves as tough guys who got drunk from time to time and who tolerated homosexuality, whereas Himmler wanted the SS to be a force 23of Aryan, disciplined, reserved men who contributed to the ‘racial quality’ of the German Volk by marrying appropriately.26

In 1932, the SS was still a small organisation, but in 1933, after Hitler became Chancellor and the Nazis took control of Germany, the floodgates opened and new recruits poured in. One of these was Morgen, who received the SS number 124940.27 The SS veterans who had been in since before 1933 suspected the new arrivals of joining simply to get ahead and called them ‘March violets’.28 When Morgen joined, the new all-black SS uniform had already been introduced to distinguish it from the brown shirts of the SA. Then in 1934, out went the SA brown shirts – in more ways than one, as Hitler had moved against the SA leadership at the end of June 1934 and had their leaders, including co-founder Ernst Röhm, executed.

In 1933, the first concentration camps, later a key focus of Morgen’s investigative talents, had been set up. In the beginning, these were uncoordinated. They were places that the local police, SS and the SA had set up to imprison and mistreat their enemies, whether real or imagined. By the end of 1933, there were over 100 of these camps scattered across Germany, which would eventually grow to over 1,000 by the end of the Second World War.29 One of these camps was at a place called Dachau in the grounds of an old gunpowder works, which was established on 22 March 1933 and which was initially staffed by Bavarian state police. Their rule over the camp inmates was short and brutal. On the first full day of Dachau’s opening alone, the Bavarian police killed four Jewish inmates.

Word of the mistreatment of the prisoners at Dachau soon got out and the Munich prosecutor’s office launched an investigation. Although this investigation got nowhere, the pressure on Himmler – who had recently been put in charge of the Bavarian 24police alongside his duties as Reichsführer-SS – was intense and he replaced the Dachau commandant, Hilmar Wäckerle, with Theodor Eicke. Eicke took immediate action to address the situation and he introduced a new model of concentration camp management, which became a template for the other concentration camps once Hitler had given the go-ahead to centralise concentration camps under the control of the SS in 1934.

Eicke’s new model involved a much tougher security regime and a uniform set of punishments for the prisoners. Under Eicke’s management, Dachau was sealed off from the outside world so no one could find out what was going on there, which meant that the death of prisoners who were shot ‘trying to escape’ would routinely avoid investigation. He restructured the camp administration and introduced hard work for all prisoners – any work, whether it be useful or pointless. Eicke also introduced a new set of rules for the prisoners, the so-called Lagerordnung. This code introduced rules for discipline and punishment, which meant that prisoners could be punished for anything at all that their guards didn’t like, with punishments including flogging, solitary confinement and execution.30

From the concentration camp prisoner perspective, life under the SS had become worse, more random and more terrifying than when the Bavarian police were in charge. But for Himmler, the dual advantage of this new system was that he could show the world that Dachau had a proper set of rules, while any crimes committed in Dachau by the SS officers could be covered up.31

By 1933, while concentration camps were still in their infancy, Konrad Morgen was a member of both the Nazi Party and the SS. For an ambitious young lawyer of that time and place, it seemed like the future was a bright one. But then in 1934, Morgen incurred the 25wrath of the Nazi Party by refusing to vote on 19 August in the referendum to give Hitler ultimate power in Germany by combining the offices of chancellor and president. On 28 August, he received an icy memo from the head of his local party, who informed him that on looking through the voting records it had been noticed that he did not cast his vote locally and please could he inform them of the place where he did vote?32

‘I stuck to my old constitutional views, and I could not see it as a good thing that all the power should be in one person’s hands and so I didn’t take part in the election,’ he told his American interrogators after the war:

As a result, the party started proceedings to expel me but then the SS took over and said, ‘This man belongs to us.’ I was reprimanded and had to remain as a candidate for SS membership rather than as a full member. I was persecuted for years because of this. In those days whenever you applied for a job the party had to be consulted and they continually made life difficult for me. I couldn’t get a job in Frankfurt and I had to leave and go to Stettin where they were short of people.33

In 1935, Morgen saw Hitler again. This time it was up close, as work on the autobahn between Frankfurt and Darmstadt had been completed and Hitler came to open it. Students blocked the streets on both sides to prevent the people getting to Hitler’s car and Hitler went past Morgen from only a few metres away. In Morgen’s eyes, the fact that Hitler was keeping his promises was a positive. People were finding jobs, the autobahns were being built and the whole place looked, well, just generally better. When he was going to 26university, he passed a factory every day. At first the place looked dreadful but after Hitler had been in power, the whole place was spruced up, flowers were planted and there were benches where the workers could smoke cigarettes on their break.

In his interview with John Toland, Morgen summed up Hitler’s success in the early years by quoting the English saying ‘nothing succeeds more than success’. Hitler had constantly proved himself to be correct against the opinions of experts. These experts had warned Hitler he wouldn’t be able to build autobahns, that he wouldn’t succeed in invading France but, of course, Hitler succeeded in these things. Morgen also held the view that right up until the last day of the war, everyone in Germany expected that Hitler would have something in reserve that would have enabled him to win. The fact that he didn’t meant, for Morgen, that at least the German people could see that Hitler had failed when he killed himself at the end of the war.34

By 1936, Morgen was enthusiastic enough about the Nazi Party that he paid £217 (in 2023 prices) in membership fees to the party.35 The Nazi Party membership documents contained pages for members to buy stamps from the party and Morgen paid for forty-two individual Reichsmark stamps and sixteen 30-pfennig (penny) stamps. Even having paid this amount for these individual stamps, there were still plenty of pages without stamps in them.36

In the same year, his short book War Propaganda and War Prevention was published by Leipzig University publisher Robert Noske. In this book, Morgen discussed the role of propaganda in leading to war and how lawyers could contribute to the cause of peace. Along the way, he suggested that the Nazis were actually working towards 27peace. However, if he was hoping to regain the party’s approval by writing this, he was to be disappointed. The official party judgement from the Official Examination Board for the Protection of National Socialist Literature of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party was damning:

The author makes false assumptions and statements for which there is no evidence. The writing contains a number of exaggerations and phrases which have no scientific basis and are therefore worthless and useless. Publication of this book is prohibited!37

Despite this, the book was published and Morgen later recalled, ‘In 1936 I published a book concerning war propaganda and prevention of wars. That book also was considered bad by the Party and was criticised in a derogatory manner. I was told that I hadn’t pointed out that the Jews were actually the instigators of the wars.’38

The year 1936 was also an important one for the SS because on 17 June, Hitler appointed Himmler as Reichsführer-SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei (head of the SS and chief of the German police). In order to centralise control of the police, Himmler created the Reichskriminalpolizeiamt with Arthur Nebe, Morgen’s future boss, in charge. In November 1938, the Nazis, in the form of the SA and the Hitler Youth, launched attacks on Jews across Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland. These attacks later became known as Kristallnacht or ‘night of the crystals’, due to the broken glass which littered the streets. Although Morgen did not record his thoughts about Kristallnacht at the time, he later described that he had discovered some of the SS officers at Buchenwald concentration camp 28had made money from these attacks on the Jews and their property, and this made him angry and all the more determined to take action against them.39

THE JULIUS SPECK AFFAIR

While all these changes to the SS would have a huge impact on Morgen’s life, for the time being he was not taking an interest in them. After studying, Morgen was occupied in training to be a lawyer in courts in and around Frankfurt prior to his qualification in 1938. This took up so much of his time that he did not get involved in either party or SS affairs. That is until Sunday 6 March 1938. The evening before, Morgen had been round to a friend’s apartment where a card game was underway. Morgen’s friend Wilhelm Müller was playing with some other acquaintances but when Morgen arrived, one of them, Julius Speck, looked up from his glass of wine and starting baiting Morgen. ‘Apparently the number of lawsuits has gone down by 25 per cent. Is that because there are too few lawyers in Germany?’

Morgen had come across Speck before at various courts as Speck was a tax adviser and economist. Having conceded that there were probably too few lawyers in Germany, Morgen asked Speck, ‘How are your cases going?’ But Speck was having none of it. He was drunk and said, very formally, ‘I apologise for my stupid remark; I have often tried to make you understand things and in the future I’ll do it in a different way if you don’t want to change!’ And with this, Speck lifted his arm as if to hit Morgen.

The exchanges carried on for fifteen minutes and eventually Speck told Morgen that if he had as few brain cells as Morgen then he would be apologising. Morgen was outraged and he decided to 29do something which was very traditionally German and very SS – he challenged Julius Speck to a duel. The very next day, he sent a memo to his SS superior officer, Captain Stroh, setting out the circumstances and asking that the SS act as the go-between for the resolution of this dispute with Speck.

The SS took disputes like this very seriously and they dispatched an SS sergeant and an SS corporal to Speck’s house. Perhaps wisely, he didn’t come to the door and so instead Captain Stroh wrote to Speck on 11 March asking how he would like to proceed. Would he like to make use of the SS arbitration procedures (in which case Captain Stroh would assign an officer from the SS to assist him) or would he like to settle the dispute voluntarily? And then came the killer sentence: if he didn’t reply by 16 March then Captain Stroh would report to his superiors that he, Speck, had refused to resolve the dispute and that this would result in a declaration of dishonour against him by the SS.

Unsurprisingly, this made an impression. Wisely, Speck decided that he would rather avoid being declared dishonourable by the SS and that it would be better if he came to an understanding with Morgen. He eventually apologised to Morgen, albeit grudgingly – Morgen had to draft an apology for him to sign.40

After qualifying as a lawyer in 1938, Morgen got his first job with the Reich Ministry of Justice as a judge at the court in Stettin (now the town of Szczecin in modern-day Poland). He knew he had to leave his home town of Frankfurt, as the local Nazi Party was determined to make life difficult for him for refusing to vote in the 1934 referendum.

Morgen did not last long at the court in Stettin. On 25 April 1939, the President of the Regional Courts in Stettin sent him a 30very formal memo, which ran to seventeen pages, signed only with his surname, Kulenkamp. The memo detailed Morgen’s failings in a court case which had taken place on 24 March 1939 in the Juvenile Protection Court.41

Morgen was sitting as one of three judges to try a case relating to a schoolteacher who was brought before the court on a charge of grievous bodily harm, having allegedly gone way past what would have been considered reasonable corporal punishment for a schoolteacher to use on a pupil. The consequences of a guilty verdict for the teacher would have been serious, meaning prison and loss of a civil service position. Morgen had been called into this case at very short notice and as a result had not read the case file in advance of the hearing.