9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

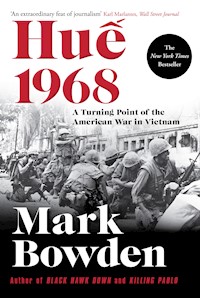

Times September 2018 paperbacks A New York Times bestseller Bowden's most ambitious work yet, Hue 1968 is the story of the centrepiece of the Tet Offensive and a turning point in the American war in Vietnam. By January 1968, despite an influx of half a million American troops, the fighting in Vietnam seemed to be at a stalemate.Yet General William Westmoreland, commander of American forces, announced a new phase of the war in which 'the end begins to come into view.' The North Vietnamese had different ideas. In mid-1967, the leadership in Hanoi had started planning an offensive intended to win the war in a single stroke. Part military action and part popular uprising, the Tet Offensive included attacks across South Vietnam, but the most dramatic and successful would be the capture of Hue, the country's cultural capital. At 2:30 a.m. on January 31, 10,000 National Liberation Front troops descended from hidden camps and surged across the city of 140,000. By morning, all of Hue was in Front hands save for two small military outposts. The commanders in country and politicians in Washington refused to believe the size and scope of the Front's presence. Captain Chuck Meadows was ordered to lead his 160-marine Golf Company against thousands of enemy troops in the first attempt to re-enter Hue later that day. After several futile and deadly days, Lieutenant Colonel Ernie Cheatham would finally come up with a strategy to retake the city, block by block and building by building, in some of the most intense urban combat since World War II. With unprecedented access to war archives in the U.S. and Vietnam and interviews with participants from both sides, Bowden narrates each stage of this crucial battle through multiple points of view. Played out over twenty-four days of terrible fighting and ultimately costing 10,000 combatant and civilian lives, the Battle of Hue was by far the bloodiest of the entire war. When it ended, the American debate was never again about winning, only about how to leave. In Hue 1968, Bowden masterfully reconstructs this pivotal moment in the American war in Vietnam.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Also by Mark Bowden

Doctor Dealer

Bringing the Heat

Black Hawk Down

Killing Pablo

Finders Keepers

Road Work

Guests of the Ayatollah

The Best Game Ever

Worm

The Finish

The Three Battles of Wanat

A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam

Mark Bowden

Grove Press UK

First published in the United States of America in 2017 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © Mark Bowden, 2017

Map copyright © Matthew Ericson, 2017

The moral right of Mark Bowden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

An excerpt from “Cheating the Reaper” is reprinted from Praying at the Altarby W. D. Ehrhart, Adastra Press, 2017, by permission of the author.

“Ballad of the Green Berets,” words and music by Barry Sadler and Robin Moore,copyright © Music Music Music Inc., 1963, 1964 & 1966. Permission given by Lavona Sadler.

Photo credits are as follows: Photo 1.1 (Che Thi Mung): Courtesy of Che Thi Mung. Photos 1.2

(Frank Doezema), 2.1 (Jim Coolican): Courtesy of Jim Coolican and Fred Drew. Photo 1.3

(Nguyen Dac Xuan): Courtesy of Nguyen Dac Xuan. 1.4 (President Johnson and General William

Westmoreland): Bettmann/Getty Images. 2.2 (Gordon Batcheller): Official Marine Corps Photo. 2.3

(Chuck Meadows): Courtesy of Chuck Meadows. 2.4 (Alfredo “Freddie” Gonzalez): Official Marine

Corps Photo A419730, courtesy of the Marine Corps History Division. 3.1 (MACV press pass):

Courtesy of Gene Roberts. 3.2 (Jim and Tuy-Cam Bullington): Courtesy of Jim and Tuy-Cam

Bullington. Photos 3.3 (Tran Cao Van Street), 5.4 (raising the American flag): Rolls Press/Popperfoto/

Getty Images. 3.4 (Mike Downs): Courtesy of Mike Downs. 4.1 (Ernie Cheatham): Courtesy of

John Salvati. 4.2 (Catherine Leroy): Photo by François Mazure, published in LIFE Magazine

(February 16, 1968). 4.3 (Ray Smith): Courtesy of Ray Smith. 4.4 (Bob Helvey): Courtesy of Charles

Krohn and Robert Helvey. 5.1 (Civilians in Hue): Photo by Kyoichi Sawada, UPI. 5.2 (Ron Christmas):

Courtesy of Ron Christmas. 5.3 (Andy Westin): Courtesy of Andy Westin. Photo 6.1

(Walter Cronkite): Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo. 6.2 (Bob Thompson): Courtesy of

John Olson, source unknown. Photos 6.3 (Dong Ba Tower), 7.2 (the Citadel): © John Olson.

Photo 6.4 (Steve “Storyteller” Berntson): Courtesy of Steve Berntson. Photo 7.1 (James Vaught):

Photo Courtesy of James J. Wilson, Sgt. E 5, B Co., 5/7 Cav. 1967-68.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Text Design by Norman Tuttle

This book was set in Dante MT with ITC New Baskervilleby Alpha Design & Composition of Pittsfield, NH

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 625 5

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 510 4

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 939 3

Printed in Great Britain

For Gene Roberts

Wisdom comes to us when it can no longer do any good.

—Gabriel García Márquez

Contents

PART ONE: The Infiltration

PART TWO: The Fall of Hue

PART THREE: Futility and Denial

PART FOUR: Counterattack in the Triangle and Disaster at La Chu

PART FIVE: Sweeping the Triangle

PART SIX: Taking Back the Citadel

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Vietnamese Glossary

Source Notes

Index

Hours before daylight on January 31, 1968, the first day of Tet, the Lunar New Year, nearly ten thousand North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) troops descended from hidden camps in the Central Highlands and overran the city of Hue, the historical capital of Vietnam. It was an extraordinarily bold and shocking move, taking the third-largest city in South Vietnam several years after America’s military intervention was supposed to have shifted the war decisively in Saigon’s favor. The National Liberation Front,1 as the coalition of Communist forces called itself, had achieved complete surprise, taking all of Hue save for two embattled compounds, one an Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) base in the city’s north, and the other a small post for American military advisers in its south. Both had no more than a few hundred men, and were surrounded and in danger of being overrun.

It would require twenty-four days of terrible fighting to take the city back. The Battle of Hue would be the bloodiest of the Vietnam War, and a turning point not just in that conflict, but in American history. When it was over, debate concerning the war in the United States was never again about winning, only about how to leave. And never again would Americans fully trust their leaders.

PART ONE

The Infiltration

1967–January 30, 1968

Che Thi Mung (left) and Hoang Thi No, village teenagers with the Huong River Squad who fought American and ARVN forces.

Frank Doezema, the army radioman who manned the guard tower at the MACV compound when Front troops attacked.

President Johnson and General William Westmorelandin the Rose Garden during the general’s November 1967 spizzerinctum tour.

Nguyen Dac Xuan, the Buddhist poet who became a propagandist and commissar for the Front.

1

The Huong River Squad

IN THE AFTERNOONalong Le Loi Street, uniformed children spill from school yards like flocks of freed birds, swinging backpacks, running or on bicycles, the boys in white shirts and shorts, the girls with their long black hair and the white flaps of their ao dai flying.

The street is Hue’s center. It runs along the south bank of the Huong River and is planted at intervals with plane trees that lean out over the busy flow of scooters and cars. On the street’s north side, along the riverbank, is a wide green promenade, and on the south side is a row of imposing stone buildings behind high walls painted in pastels of green, yellow, red, brown, and pink. Across the water rise the mottled, forbidding stone walls of the Citadel, a monumental fortress from another era. The river’s name, Huong, evokes the pleasing scent of incense or the pink and white petals that float downstream in autumn from orchards to the north. The Americans called it the Perfume River.

In 1968, there were more bicycles than scooters and cars beneath the trees on Le Loi Street. The image of a pretty girl on a bike in an ao dai, the traditional tunic with flaps in front and back, and a traditional conical hat—non la—was on the cover of the pocket guide GIs were issued on their way to the war in Vietnam.2

One of those cycling girls in January of that year was Che Thi Mung. She was eighteen and as pretty as the picture on the handbook. Che was a village girl with little schooling. Riding her bike in Hue, she was the picture of innocence: slender with a round face, big eyes, and high cheekbones. She worked with her family in the rice paddies and helped weave palm leaves from village trees into non la, which she sold on the city streets. She would stack the hats and strap them to the back of her bike.

But Che was neither as innocent nor as friendly as she looked. She knew nothing of the global clash of ideas that brought American soldiers to Vietnam, but the war was her life. Her position in it was dead certain. With all the passion of youth, she hated the Saigon regime, the Republic of Vietnam. This enmity was largely an inheritance. Before she was born, her father had fought with the Viet Minh against the French, and when she was a child he had been imprisoned for years by the Saigon regime, which had followed the French. In her mind they were the same, only now the shadow behind the local oppressor was not France, but the United States. Her father, a bricklayer, had been fighting his whole life. For Che, the war had turned even more personal two years earlier, when the ARVN killed her big sister, a leader in the VC underground. She knew the regime’s soldiers as nguy (fake), a word that in Vietnamese suggested a familiar Asian face masking an alien soul.3

After her sister was killed, the nguy had come looking for collaborators in Van The, her village, a small community of farmers and tradesmen in the Thuy Thanh district southeast of the city. It was off the main road and surrounded in all directions by well-tended rice fields, a flat and outwardly placid landscape. The weather was damp through most of the year but especially during the coastal region’s wet months from December through February, which were filled with cool days shrouded in gray mist. Far to the west were the stark green peaks of the Central Highlands; to the east, just a few miles distant, were beaches and the South China Sea. About three of four people in Van The shared Che’s feelings about the Saigon regime, so it was friendly ground for the VC. Her father was hidden by friends after Che’s sister was killed. They knew that once the nguy figured out who she was, they would unearth his record and come looking for him.

When they came, they found empty bunkers beneath Che’s house. Such shelters were common. Villagers dug them to hide from bombs or shells, and sometimes they were used to hide weapons or the VC. Sometimes village boys were sheltered there to avoid impressment by either side. So the ARVN could make what they wished of the bunkers.

In Che’s case, they were suspicious enough, weighed with the actions of her sister and the absence of her father, for her arrest. She was taken to an ARVN post in the city with her mother and paternal grandfather. Interrogators poured soapy water down her nose and throat until she choked and her ears rang and head and throat stung. They demanded she tell them where her father had gone and the names of the VC fighters from her village.

She cried and pleaded. She was just a girl! She told them she knew nothing. Why were they tormenting her? Did they think the VC confided in sixteen-year-old girls? Didn’t they have daughters? Sisters? For the rest of her life she would be proud of how tenaciously she protected her secrets. She told the nguy nothing.

She had joined the Viet Cong herself four years earlier, its Young Pioneer Organization.4 She was fiercely proud of her martyred sister, heartbroken over her death, fearful for her father, and determined to live up to their example. When she and her family were released, martial law was imposed on Van The. Most deeply resented was a curfew that confined the villagers to their homes after seven in the evening. But the nguy did not live in the village. They could not be there all the time, and they could not know which neighbors to trust. It was easy for fighters like Che to avoid the patrols and to attend nightly meetings and training sessions. As for the rest of the village, the crackdown just generated anger—and recruits.

Che would sometimes see Americans with the ARVN troops. They wore similar uniforms but the Americans were easy to spot even from a distance because they looked so different. For one thing, most were bigger. At night she and her family listened to stories on the radio of American bombing in North Vietnam, imagining the death, destruction, and misery, but she did not fear or hate the Americans so much as she did the nguy, who seemed to her much worse. They had sided with foreigners against their own people. They spoke her language and were Vietnamese in all respects except the most important.

For the two years after her arrest and interrogation, she lived a double life, a committed revolutionary at night, and a law-abiding citizen of South Vietnam during the day. She found work at the same ARVN post where she had been tortured, cleaning and doing odd jobs. She had been cleared and released, and so many were subjected to this treatment that even if suspicions about her lingered, she little feared being remembered. She would bicycle into the city, selling her hats and working at the post, and most evenings she would ride home and attend meetings where she and other village girls sharpened bamboo spikes for booby traps. She would stand watch and spread the alarm whenever the nguy or Americans approached.

The cadre she supported, her sister’s, took portions of the village harvest and carried it up to the hidden jungle camps in the highlands, what the troops referred to simply as xanh (the green). Mostly it was boys who did this work. The girls encouraged children to join the revolutionary youth groups, and tried to recruit villagers to the cause. Che would remind them of the onerous curfews, the rudeness of the soldiers who swept through periodically, and the arbitrary arrests and invented charges. She told them that the peace and freedom promised by the nguy and their American controllers was illusory. Their country was at war and would remain at war until the invaders and traitors were gone. The real Vietnam would rise she said. It would be united. She envisioned a future where the free Vietnamese people worked together to improve life for all.

She was eager to fight for it. When she turned seventeen, a year after her arrest, she was admitted to the Youth Union,5 where she began working directly with the commune guerrillas. In their nighttime sessions, they now learned to break down, clean, and rebuild automatic rifles like the AR-15 and AK-47; how to shoot them and bazookas, B-40 rocket launchers; and how to handle grenades. These grenades took seven seconds to explode after you pulled the pin, so you had to count calmly to five before throwing them. Che took part in a hit-and-run attack on a nguy outpost one night that year and fired her weapon at the enemy for the first time.

Then, in October 1967, the most thrilling thing happened. She was selected to join ten other girls in a special squad. It would be led by Pham Thi Lien, a twenty-year-old native of their village who had fought with Che’s sister. During the raid when Che had been arrested, Lien had been outed. She had escaped to North Vietnam, where she had received formal political and military training. On her return, she picked only the most committed young women from several villages in the area. Along with Che she chose Hoang Thi No, whose parents were already living underground with the VC. Hoang was so small and thin she looked even more harmless than Che, but she had worked with her on recruiting and also maintaining underground shelters. When the two girls from Van The met with the others in their new squad, Lien told them their mission was to prepare for a great push to be called Tong-Tan-cong-Noi-day(General Offensive, General Uprising). It would take place during Tet, which in 1968, according to the Chinese calendar, was to be Mau Than, the Year of the Monkey. Its most important part would be an attack on Hue, from which they would expel, once and for all, the Americans and the nguy. From the north would come thousands of well-armed, well-trained soldiers who would join with the VC and with other local patriots. The people would rise up. The war would end. The promised day of self-rule was at hand!

Lien’s group, later called the Huong River Squad, was one of many mobilized in secret during those months. The girls felt part of something on a grand scale, and it was not just talk. Lien told them they would have to leave their families. Four specific missions were assigned: to spy on the nguy and American forces in the city; to recruit civilians to join the uprising and provide support; to train them with weapons and tactics; and to build a committed core who, when the battle began, would carry the wounded to medical stations in the rear and help feed the army. Weapons, ammo, food, and medical provisions all would be smuggled, stockpiled, and made ready. Pretty girls were not perceived as a threat in the city. They moved around freely. They could watch the military and police posts, mapping entrances and exits, defenses, and gun positions, and noting the enemy’s numbers and routines. They could document the homes and habits of Westerners living in Hue. There were scores of American and European civilians living and working there, everyone from undercover CIA officers to peace activists. They could record the home addresses and routines of traitors, prominent officials in the Saigon regime, police and military leaders, and even lesser citizens whose loyalty was suspect. For all of these there would be a reckoning.

The girls were given money to rent homes in Hue. Che left to live with a family in Dap Da, a south bank neighborhood where the Nhu Y River emptied into the Huong, a short walk east of the city’s center. The family she joined lived in a run-down house of brick and stone that was owned by a teacher who lived there with his son, a tailor; and his granddaughter, a schoolgirl. During the day, setting up on the sidewalk, Che would weave and sell hats, and she would watch. At intervals she would pick up her wares and bike west down Le Loi Street, past Hue University, the city hospital complex, the police headquarters, the prison, and the province headquarters. She kept a close eye on the river landing across from the university at the foot of the Truong Tien Bridge where American navy vessels came and went. Che’s comrade Hoang sold hats and kept an eye on the Americans’ favorite Huong Giang Hotel, among other spots. Along with the other girls, working over months, they drew a detailed portrait of Hue’s military and police posts.

One of Che’s targets was the busy American post, the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) compound, just two blocks south of the bridge. It was a rectangular enclosure formed by nondescript two- and three-story buildings and fencing. Inside was a large courtyard with a parking lot and a tennis court—used mostly for barbecues. The lot was filled with olive-colored Jeeps and six-by-six trucks. A high steel fence—topped with barbed wire and studded with flares and mines rigged to detonate if disturbed—surrounded the perimeter. There were only two gates, guarded by high towers. Outside them on the sidewalk were sandbag bunkers. It was a small urban fort without especially heavy defenses. There was always at least one bored soldier with a machine gun in the front tower, gazing down blankly on the constant flow of bicycles, cars, rickshaws, and scooters. Daily, Che counted the men and vehicles that came and went, and noted entrances and exits, guard shifts, the number and kinds of weapons.

Because there was no running water at the house in Dap Da, she walked with other neighborhood girls every evening to a public water fountain where they filled containers to carry home. It gave them an excuse to be on the streets after the evening curfew. The line of girls in their colorful silk blouses at the water fountain was catnip for the nguy, who were plentiful in that neighborhood. Across the street from the fountain were a military school and a brothel. The girls chatted and teased and flirted with the soldiers coming and going from both places, and learned a lot. Flirting was particularly useful. Once a nguy soldier was in the proper mood, Che had only to ask when his guard shift ended. In time she developed a working knowledge of the schedules at all the posts she observed. She never took notes. She committed all the details to memory and reported them back to Lien.

The girls were not told exactly when the Tong-Tan-cong-Noi-day would begin, but when that day came—and it would be soon—they would be called back to the village. From there they would lead NVA and VC troops into the city in darkness for the surprise attack. Once the fight started, they would assist, carrying the wounded and supplies.

To Che and the other girls on the Huong River Squad, it would be the biggest moment in their lives.

2

Thirty-Nine Days

IT HAD BEEN a long year for Frank Doezema. He was heartily homesick. Each time he wrote home to Shelbyville, Michigan, near Kalamazoo, he would note the days left in his one-year tour in Vietnam. On January 21, he told his brothers: “It won’t be long now. Look out world, here I come! When I say world, I mean the good ole USA or Michigan or Shelbyville or just plain home . . . Let’s see, 55 days, that’s eight weeks.”

He knew exactly what he would do when he returned: work on his family farm and eventually run it, either alone or with his brothers. Cornfields and cows were all he wanted, careerwise. He’d collected his diploma from Kalamazoo Christian High in 1966, and that had closed the book on school. Like all young men with a clear vision of their future, Doezema was in a hurry. He had his eye on a girl he intended to marry, although she didn’t know it yet. He’d have been well along already, with farm and family, if not for the draft.

Every healthy male high school grad in the United States in 1966 without college plans was immediately draft bait. It was a stubborn reality, like taxes. Nearly everyone had a father or uncles who had fought in World War II or Korea, or both, and many had grandfathers who had fought in World War I. War was stitched deep in the idea of manhood. It was portrayed heroically in popular films and TV shows, books, and even comic books: stories of men bravely defying death and besting foes in faraway places for God, family, and flag. Doezema was not eager to be a soldier, but he didn’t question the call. In fact, knowing there was no draft deferment for farmwork, he’d sought out the most efficient way to meet his obligation. He took advantage of an army program—designed to meet the urgent need for men in Vietnam—that would halve his commitment from four years to two. And as he’d expected, he was in Vietnam within months of completing basic training.

He was an authentic Michigan cornstalk: tall and thin with a blond crew cut and a long square jaw. Trained as a radio operator, he spent the first six months in-country assigned to a marine captain named Jim Coolican, who worked as an adviser to an ARVN battalion. Coolican rejected Doezema at first. The captain stood about six foot five, and towered over the Vietnamese soldiers he advised. Enemy snipers targeted officers and Americans. An officer and his radioman had to stay close together—the radio was needed to call in artillery and air support—and Coolican worried that being with Doezema, who was nearly as tall as he was, would double the danger. It was especially dangerous for Doezema because a radioman carried the unit strapped to his back: it was bulky and had a high antenna. Coolican considered himself brave, but he wasn’t stupid. Still, Doezema pushed. He liked the captain and he liked the idea of seeing real combat during his tour. And from what he’d heard, the ARVN airborne troops mixed it up with the enemy often. Coolican eventually gave in, and the two had worked together seamlessly.

They saw action often. Their battalion,6 part of ARVN’s First Division, was deployed in I Corps, the country’s northernmost sector, which encompassed five provinces of South Vietnam and stretched from south of Hue all the way north to the demilitarized zone (DMZ) and the border with the North. This was the easiest place for NVA troops to infiltrate, and it was obvious that Hanoi was planning something big, because many soldiers were coming. In the fall of 1967, there had been frequent violent clashes in this sector, and contrary to the poor reputation of South Vietnam’s forces, the men Coolican and Doezema served with were aggressive and competent. During those months, the two tall Americans saw far more combat than most of their countrymen, and despite their size, neither had been hit. In time, they felt lucky to be paired. They worked shoulder to shoulder in the field during the day, ate their meals together, and slept side by side, often softly talking into the night. They shared everything. At twenty-seven, Coolican was eight years older than his radioman, who always called him Captain or sir, but in time there was little barrier of rank between them. Coolican came to feel like Doezema’s older brother.

Americans who landed in Vietnam were strangers in a strange land. Few of them knew the language, the history, the culture, or even, except in broad outline, the nature of the conflict, which actually differed from zone to zone. Coolican and Doezema were having a far different experience. They lived and worked with their Vietnamese counterparts. The captain had been given some language training, but neither he nor his radioman spoke the language well enough to say anything beyond a few necessary words. And yet they had both developed a strong respect and affection for their ARVN counterparts.

To most American soldiers, the local forces were known as Arvin, and the name was not applied kindly. It suggested a caricature: a small Asian man in an oversize American helmet and uniform (cast-off American sizes often fitted Vietnamese men poorly), inadequately trained, ignorant of basic infantry tactics, equipped with Korean War–vintage weapons, incompetent, reluctant to fight, and all too often given to thievery and desertion. Some of the South Vietnamese men pressed into service fitted this mold, just as some of America’s more reluctant draftees fell short of the ideal. All too often, the officers who led them were incompetent and corrupt. It was an ongoing problem. Largely out of necessity, American combat soldiers were aggressively insular. When they were not on patrol they stayed behind defensive perimeters of barbed wire and mines. They ate American food, shopped for American products at the PX, watched American movies, and listened to American songs on the radio. Fraternizing with the locals was discouraged—although whorehouses did brisk business. So the only Vietnamese most soldiers encountered were scouts, translators, whores, workers hired to perform menial jobs on American bases, or those who peddled goods and services nearby—licit and illicit. Enterprising Vietnamese mixed basic mercantile lingo with simple GI slang, and added coinages of their own: “numbah ten” for the worst, “numbah one” for the best. The primitive dialect reinforced disdainful stereotypes, even if the peddler who spoke broken English had language skills that exceeded his customers’. And most Americans viewed the locals with suspicion. The contemptuous word “gook” was applied not only to the enemy; there were gooks who were the enemy and then there were “our gooks.” And even those more kindly disposed were often patronizing, seeing the “good gooks” as worthy little people stuck in a primitive past. Racism colored the alliance from top to bottom.

Coolican’s experience was the opposite of all that. With the ARVN troops he “advised,” he was the ignorant and inexperienced one. The very idea of a college boy from suburban Philadelphia having something worthwhile to impart about combat was laughable. The Vietnamese officers Coolican served were far better soldiers than he was. They had been at war for years. The only important thing he had to offer them was Doezema’s radio, the ability to dial up American air and artillery—a game changer. This was why he was important to them, not because he had knowledge to impart. Without his radio, he was nothing more than a tall marine who drew fire.

The realization was humbling. Coolican found himself defending the ARVN troops from knee-jerk American scorn. He had been an air force ROTC cadet at St. Joseph’s College before he opted for the marines. Vietnam had been his goal. He was an idealist, and a true believer. He had grown up trusting his elders, and accepted that just as his father’s generation had fought in Europe, Japan, and Korea to protect the American way of life, his generation had its own role to play holding the line against Communism. Kennedy’s inaugural address, with its evocation of the “torch being passed to a new generation,” had spoken to him. He completed boot camp and infantry training over summer vacations, and upon graduation he was commissioned a second lieutenant. His experience in Vietnam, coming up on a year now, had only deepened his commitment to the cause and his career. He was exactly where he wanted and needed to be.

He and Doezema split up toward the end of 1967. Coolican had sought and received a transfer to the Hac Bao (Black Panthers), an elite ARVN unit with a reputation for ferocity and skill. Hand selected, they wore distinctive black fatigues when they were not fighting in the jungles. General Ngo Quang Truong, commander of the ARVN First Division at Mang Ca, the military base in the northeast corner of the Citadel, used them as a rapid strike force.

For Doezema, the change meant his days of fighting were all but over. Parting from Coolican, he went first to a small American compound on the outskirts of Hue, and then to the MACV compound. He still worked as a radio operator, but now was surrounded by other Americans. The streets outside were comparatively safe. In the heart of this bustling city it was easy to feel that the war was a minor conflict at the wild edges of a thriving South Vietnam. There were regular convoys back and forth from the marine combat base at Phu Bai, eight miles south, and beyond it to the larger one at Da Nang. American vessels came and went from the boat ramp on the Huong’s south bank. The war had visited the old capital city so infrequently in the previous years that the compound was regarded as a rear post, well out of harm’s way.

He had downtime, and with it he had things to do. There were curbside restaurants to indulge his new taste for Vietnamese food, bars, museums, parks, and even historical sites like the old emperors’ tombs and the ornate royal palace. The beaches of the South China Sea were just a few miles east. Doezema tried out the smattering of Vietnamese he had learned with Coolican. He would sometimes use his radio to call the captain, still humping around the countryside with the Hac Bao, and they would chat at night like old times. The farm boy was coasting through the final months of his adventure, crossing off the days on his calendar until his real life resumed. He had friends who would stop by for two- or three-day visits, staying in his room. They noticed that the Vietnamese girl who cleaned up had a crush on the tall blond American who treated her with such respect and made an effort to speak her language.

Here was one more unusual thing about Doezema. He made Vietnamese friends. One was a twelve-year-old boy whose family had lived adjacent to his first post in Hue. The boy’s name was Quy Nguyen, and he lived in a big house with a walled garden just outside the city. He was the eldest of seven children. Doezema and his buddies would drive out to the Nguyen house with candy and teach the children English phrases and give them rides in the Jeep. In return, they were treated to large Vietnamese meals that put the compound mess to shame. On one of those trips in January, Doezema told Quy that he would soon be going home. He put his camera and his watch on a table and told the boy he could have his pick. Quy chose the camera.

The letter of January 21 to his brothers Ardis and Bill displayed both his homesickness and his sense of humor:

Here it is Sunday again and I have to work all day. It’s a pretty nice day too. The misquitos [sic] are getting pretty thick again. We still haven’t had much of a monsoon season or cold weather either like everyone told us we would. It’s OK with me though. I will be glad to get back to all that beautiful snow though.

Last Sunday afternoon Bob [Mignemi] and I went down to my friend’s house in Hue & visited with them a while. Yesterday afternoon we had a practice alert in the compound. Only about 1/3rd of the people were there so it really wasn’t very profitable.

It’s 10:00 already & a lot of late reports are coming in from last night’s activities. Just mostly small contacts like ambushes being ambushed while on their way to an ambush site. We’ve got a brigade from the 1st Air Cav in our area now. That should make the V.C. think twice. Phu Loc [an American base south of Phu Bai] still takes sporadic fire once in a while. They’ve got a lot of nearby mountains so it’s hard to locate the enemy.

I made it to the movie last night. I sure get homesick when I watch a movie with “round eyes” in it. It won’t be long now, though. Only forty-eight more days. A lot of new people are coming in & now it is my turn to laugh. I can’t hardly imagine what it will be like to get back. Alls I know is that it’s going to be great. I can hardly wait. I sure do dream about it a lot lately. I’m not the only one though. 3 guys in our hootch are going home soon & that’s all we talk about. Ernie Barbush is from Pittsburgh & goes home February 20th. Bob Mignemi is from New York & he goes home March 1. I go home shortly after Bob. Ernie gets out of the Army in July but Bob and I get out at the same time. That will be a happy day also.

How is everyone doing these days? Fine I hope. I imagine the guys aren’t doing too much in all that cold weather. Is the roof over the lot finished & if so how does it work? At least it will keep the snow off the lot in this weather. What else is new around there? Keep me posted, OK? I’m fine, just homesick that’s all. That will be changed soon though.

Well I guess I’ll close here. I’ll see you very soon. Your brother, Frank.

On January 30, his countdown had reached thirty-nine days. That evening he was expecting a visit from his friend Coolican. The captain’s Hac Bao unit was taking off a few days for the Tet holidays, so he planned to drive down to the American compound. There would be beer and barbecue and conversation. It was likely to be the last chance Doezema would get to see him before flying home.

3

Spizzerinctum

ON FRIDAY MORNING, November 17, 1967, President Lyndon Baines Johnson had taken breakfast in bed. A big man, he was imposing even in his bathrobe. Three TVs were going across the room, each tuned to one of the three networks. Phones rang. Aides brought messages and documents to be signed. At his bedside sat General William Westmoreland, also in his bathrobe, eating breakfast off a tray, chatting between bites.

Westy, as he was known, was enjoying himself. His long march up the ranks of the US Army had led him here, to the bedside of the president of the United States. He wasn’t just LBJ’s most important general; he had also become a vital ally, a confidant, or at least he felt like one. Johnson was good at that. He had been summoned from Saigon, where he led the American military effort, the MACV.

The general and his wife, Kitsy, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Margaret, had been assigned upstairs quarters in the White House. The fifty-three-year-old former Eagle Scout from South Carolina didn’t drink, smoke, or swear; the most colorful expletive in his vocabulary was “dad gum.”7 He was a West Pointer and had been an artillery commander in World War II. After that his career had been a steady upward climb. Once he’d won the war, which he fully expected he would—and soon—there was even talk of his running for president. These were heady days. He and Kitsy had dined the night before with the president and Democratic congressional leaders. Afterward, Johnson had even come upstairs for a late-night chat, loosening his tie and propping his big feet on a coffee table. Before the Westmorelands finally turned in, the two beds in their room had been pushed together, and inadvertently the phone, which ordinarily sat on a table between them, had been left underneath. So when it rang with the president’s unexpected breakfast invitation early that morning, the four-star general had to crawl down and answer it on all fours.

“Yes, Mr. President. Yes, I’m awake, Mr. President. Not at all, Mr. President. I’ll be right down, Mr. President.”8

Even in his bathrobe, Westy looked the way generals were supposed to look: ramrod tall and fit, square jawed. His close-cropped hair had gone regally white at the temples while his thick eyebrows stayed dark, so there was something positively eagle-like about his gaze. Johnson had met him at West Point, where Westy was superintendent. After the fateful decision was made in 1964 to ramp up America’s presence in Vietnam, Johnson tapped the steely-looking general he’d met at the Point to take charge. Three years had passed, and throughout ups and downs—and steady requests for more troops—Westy had calmly and persuasively predicted victory. Despite a growing and unseemly chorus of opposition throughout the country, he never wavered. The war was difficult, but it was progressing according to plan, from triumph to triumph. This was in keeping with not just his own can-do personality, but also the can-do spirit of the entire US military, which had proved itself in World War II and in Korea and considered itself with some justification to be the finest fighting force in the history of man.

If you were to sculpt a general to command this force in battle, Westy was that man. Even without all the stars and medals and ribbons on his dress uniform, he looked the part, knew it, and put great store in it.9 Leadership was partly showmanship, and Westy neglected no means of projecting confidence, strength, and moxie. This last quality was key in war fighting, but away from the battlefield it was harder to display. Westy found ways. When he was presiding at West Point, he’d hung a banner across the “poop deck,” the balcony high over the cadets’ mess hall from which important announcements were made, that read: SPIZZERINCTUM. The cadets squinted up at the word, scratched their heads, and consulted their dictionaries. It was a southern colloquialism for vim, vigor, or gumption. A man who stood firm in the face of adversity was said to have spizzerinctum. Superintendent Westy wanted his cadets to have it.

Firmness in the face of adversity had defined his performance as MACV commander. It was not the highest position in the US military, but because it was responsible for the war, it was the most important. Westmoreland reported to Admiral Ulysses S. Grant Sharp, the commander in chief, Pacific, in Hawaii, who reported to General Earle Wheeler, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs. These top commanders shielded Westy from the doubts and criticism in Washington, not that he needed shielding. The louder the opposition, the more certain he seemed to be of his course. In 1966, speaking in Manila, he summed up his progress by noting a great improvement in kill ratios—the number of enemy killed per allied deaths—and claimed success by every other measure: “The number of enemy soldiers who surrender in battle has also increased,” he said. “The number of casualties he leaves on the field of battle, rather than carrying them off, is rising. The stream of refugees choosing government security over Vietcong domination continues to grow. The flow of information about the enemy from the people in the countryside increases weekly.”10 In July 1967: “We have made steady progress in the last two years, especially in the last six months.”11 On his way to this White House visit, he had stepped off the plane in Honolulu and told reporters that the war effort was “very, very encouraging. I have never been more encouraged in my four years in Vietnam.”12

This invitation as the year drew to a close wasn’t just about hanging out with the president; it was also about showcasing some of that spizzerinctum. Johnson felt America needed a strong dose of Westy’s can-do. Protesters now dogged the president’s every public appearance, and his critics in Congress had become relentless: movements were afoot in his own party to deny him a second full term. The goddamn Kennedys and their people were bailing on him over Vietnam—Senator Robert F. Kennedy was known to be weighing a run for the White House himself—and they were the ones who’d gotten him into it. Pay any price, bear any burden, my ass! One by one the Camelot crew was going soft on him, even Bob McNamara, JFK’s (and LBJ’s) wunderkinddefense secretary, one of the prime theorists behind “limited warfare,” and an early advocate of the war.

Johnson had had it. He was pushing back. He had in mind a weeklong course of backbone stiffening. America was a country that still respected its generals. Westy’s eagle countenance and steely optimism would be on display all week in interviews and speeches, most notably a major address in four days at the domestic enemy’s inner sanctum, the National Press Club.

The president was privately wearying of the war. He felt trapped by it. It wasn’t something he’d started, after all; it was an onerous inheritance from three previous presidents. In the early 1950s, Harry Truman had sent arms, military trainers, and advisers to the French (then colonial masters of Vietnam), who were battling a nationalist movement called the Viet Minh. As the French hold on the country slipped, Truman’s successor, Dwight Eisenhower, declined to send American combat troops (his vice president, Richard Nixon, favored the idea), but upped the number of arms and advisers. The French were chased from the country in 1954 after a stunning military defeat at the northern outpost of Dien Bien Phu. They signed an accord with the Viet Minh in Geneva granting independence to Vietnam, but temporarily partitioning it at the seventeenth parallel. The Viet Minh, under their leader Ho Chi Minh, set their capital in Hanoi, and a separate French-backed government was established in Saigon. The Geneva Accords called for elections in 1956 to reunite the country. But as it became apparent that Ho’s Communist government had overwhelming popular support—Eisenhower later estimated that if the elections had been held in 1954, Ho would have captured 80 percent of the vote13—South Vietnam’s president, Ngo Dinh Diem, reneged on the election. The United States, which had not been a party to the Geneva Accords, continued to back Diem, while the Viet Minh, newly reconstituted as the Viet Cong, began a war of resistance, aided by North Vietnam’s regular army. Most people didn’t give Diem much of a chance in that fight, but since Hanoi was a single-party Communist state, and Saigon was ostensibly a democracy, this remote civil war in faraway Indochina assumed, for some, global import. Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, had famously begun his tenure with that ringing promise: “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” Vietnam became the case in point. In a letter to Diem in 1961, Kennedy wrote, “We are prepared to help the Republic of Vietnam to protect its people and to preserve its independence.”

Once begun, a military commitment is a hard thing to contain. Even a small number of American troops, no matter how limited their mission, had to be protected and supplied. Under Kennedy, the advisory force grew significantly, as bases, ports, and depots were established to safely house, feed, and support those directly engaged. Then came Kennedy’s assassination and Johnson’s presidency. As the nation grieved, LBJ shouldered the slain president’s ambitious agenda and made it his own: economic policies, civil rights, the moon program—and Vietnam. How would it have looked to pull the rug out from under the martyred president’s most ambitious stand against Communism? Johnson upped troop levels significantly in 1964, doubled the draft, and installed Westy as MACV commander. The following year he unleashed a vicious bombing campaign over North Vietnam, arguing that it was not “a change of purpose . . . it is a change in what we believe that purpose requires.” Later that year, he for the first time authorized American troops to engage directly in ground combat, claiming this did not represent an expansion of the war effort—despite the fact that it obviously did.14 Over fifteen years and four presidents the war effort had evolved from a peripheral support mission to a vital and binding national cause. Johnson said in 1965: “If we are driven from the field in Vietnam, then no nation can ever again have the same confidence in an American promise, or in American protection.”15 A year later, in 1966, there were 385,000 American troops in Vietnam. They were now doing the bulk of the fighting, and Johnson speculated that victory might ultimately require almost double that amount.16

The number, which included Jim Coolican and Frank Doezema, was up to a half million by the time Westy arrived in the United States for this spizzerinctum tour. American troops had for the most part fought valorously and well for three years. They were highly mobile and well trained, backed by overwhelming airpower, superior weaponry, and seemingly endless reserves of ammo, fuel, and men. Handling the logistics of the war effort alone—providing food, clothing, shelter, fuel, ammo, etc.—took over fifty thousand soldiers.17 More than nineteen thousand Americans had given their lives. The Republic of South Vietnam had become a de factoAmerican colony. But despite this enormous investment of blood and treasure, the advance of Communist forces had been merely stalled, not defeated. In April 1967, Johnson had dispatched General Creighton Abrams to Vietnam as Westy’s deputy. Abrams, a famous tank commander in World War II, had more combat experience than any other officer in the upper ranks of the US military, and some saw his appointment as a hint that LBJ was not entirely satisfied with Westy’s progress. The White House denied it.18 To a swelling chorus of war critics at home, the huge application of American force had accomplished only one thing: it had greatly increased the killing.

This was an ugly truth, but one that Westy embraced. Battlefield deaths were something you could count, and the general, like the thoroughly modern manager he was—very much in McNamara’s mold—placed great stock in data. He could dazzle an audience with charts and numbers and well-ordered explications, arranging the messy work of war into neatly quantified categories and crisply reckoned “phases.” Westy was a demon for phases. And the body count was his go-to metric. It was stark and final, and it offered something that appeared irrefutable, so much so that it became a substitute for strategy. Missions were planned and their success was measured not by how they advanced a well-defined goal, but by how many casualties were inflicted.19 In that 1966 Manila speech he had said: “The ratio of men killed in battle is becoming more favorable to our side. From a little better than two to one last January, the ratio has climbed to more than six to one in favor of our side.”20 Westy argued that the ratio so heavily favored allied forces that in time the mounting toll would buckle Hanoi’s resolve.

And Johnson was a convert. Body counts were the first thing he asked for in regular war briefings. He bragged that his general in Vietnam killed thousands of enemy personnel for every one man he lost: “He has done an expert job; anybody that can lose four hundred and get twenty thousand is pretty damn good!” the president told Washington Star reporter Jack Horner when questions were raised about the general’s performance in early 1968.21

What became increasingly clear, however, was that Westy’s counts were bogus. He believed them—he was not the first general to welcome statistics he wanted to hear—but the numbers emerged from an intricate origami of war bureaucracy: South Vietnamese, North Vietnamese, and American. The truth was bent at every fold for reasons that went beyond propaganda to self-interest, sycophancy, and wishful thinking. In Hanoi there was no pretense of truth whatsoever; “facts” were what served the party’s mission. American commanders, on the other hand, supposedly embraced a more enlightened standard. Accurate information was essential to war planning, and, unlike Hanoi, the United States was dogged at every turn by an independent press. But, in practice, there was every incentive for field commanders to inflate or even invent body counts. It was how their performance was assessed, and it became one of the greatest self-reporting scams in history. Everyone knew it was going on. Some of the more senior commanders discouraged the practice, but it was so widespread—and so hard to disprove—that few if any field officers were ever disciplined for it.22 No one in a position to know better took the numbers that emerged from this process seriously. But Westy was far enough removed to embrace them. He was the last man up the self-reporting chain. The absurd body counts and kill ratios were proof of his leadership. He sold them to LBJ, who in turn presented them as fact to the American people.

But what if the death toll—which despite the distortions clearly favored the Americans—was having the opposite effect? What if heightened punishment by US bombs and guns actually fueled Communist resistance, inspiring ten recruits for every dead enemy fighter? Harrison Salisbury of the New York Times wrote an influential series of stories in December 1966, reporting from North Vietnam, where he witnessed firsthand the extensive damage done by American bombs. Salisbury reported that the death and destruction seemed to have only a small impact on the country’s economy, and had in fact spurred the people’s will to fight on. In the final story in his series, Salisbury wrote, “The basic question would seem to be: Has all this hurt the North Vietnamese so much that they are ready to quit? Their answer is, ‘By no means!’ And they say that they expect their task to get a lot harder before it gets easier.”23

Salisbury’s insight came as no surprise to realists in the government. A secret Rand Corporation study for the Pentagon had concluded in 1966 that while the bombing had caused widespread hardship and even food shortages in the North, “there is, however, no evidence of critical or progressive deterioration or disruption of economic activity . . . As to the effects of the war on public morale and effectiveness of government control, the cautious guess should be that they have redounded to the regime’s net benefit. The bombing specifically has probably produced enough incidental damage and civilian casualties to assist the government in maintaining anti-American militancy, and not enough to be seriously depressing or disaffecting.”24 A CIA report completed in 1968 found similarly: “The war and the bombing have eroded the North Vietnamese economy, making the country increasingly dependent on foreign aid. However, because the country is at a comparatively primitive stage of development and because the bombing has been carried out under important restrictions, damage to the economy has been small. The basic needs of the people are largely satisfied locally. Imports from Communist countries have enabled North Vietnam to make up for losses in industrial production and to take care of new needs created by the war.”25

For war hawks like Curtis LeMay, one of the architects of successful World War II bombing campaigns over Europe and Japan, the answer was more and bigger bombs. He said the United States should issue Hanoi an ultimatum, and, if they refused it, “bomb them back into the Stone Age.” Johnson was mindful that fully unleashing America’s airpower risked drawing China or the Soviet Union into the war, but he was hardly squeamish. More bombs had been dropped in North and South Vietnam by the beginning of 1968 than had been dropped over Europe in all of World War II, three times more than were dropped in the Pacific theater, and twice as many as in Korea.26 LeMay’s prescription sounded right to those—perhaps even a majority of Americans—who felt it was high time Ho’s nettlesome regime was simply erased from the planet.

McNamara resisted escalation for reasons quite apart from morality or even avoiding World War III. He was beginning to believe the war could not be won. For nearly a year, in private, he had been saying so. In a secret October 1966 memo to Johnson he recommended that further investment of troops be slowed and their number capped. He believed the previous year’s enormous military investment had “blunted the communist military initiative,” but his careful reading of even the tainted metrics had begun to reveal the truth. “This is because I see no reasonable way to bring the war to an end soon,” he wrote. “Enemy morale has not been broken—he apparently has adjusted to our stopping his drive for military victory and has adopted a strategy of keeping us busy and waiting us out (a strategy of attriting our national will). He knows that we have not been, and he believes we probably will not be, able to translate our military successes into the ‘end products’—broken enemy morale and political achievements by the GVN [government of Vietnam].” He noted approvingly high enemy losses, “allowing for possible exaggeration in reports,” and called Hanoi’s infiltration routes “one-way trails to death.”

“Yet there is no sign of an impending break in enemy morale, and it appears that he can more than replace his losses,” McNamara wrote, both by sending more NVA troops down those “one-way trails,” and by recruitment in South Vietnam.27

The defense secretary also knew that more and bigger bombs accomplished nothing. He had pushed for the bombing campaign in 1964 because he believed it would slow the southward movement of the NVA and armaments and inflict enough pain on the North to force Hanoi to negotiate an end to the war. But beyond the immediate death and destruction, the bombs had changed nothing. The economy of the North actually grew in 1965 and 1966. There was a sharp decline in 1967, the bombings having taken their toll, but it was more than offset by aid from the Soviet Union.28 Troop movements southward had not slowed; they had kept pace with America’s escalation. McNamara, the supreme quantifier, could no longer fight his own data.29 The numbers were in. Bombing had failed.

How do you bomb a nation into the Stone Age when, in modern industrial terms, they are not that far removed from it? North Vietnam was an agricultural society that lacked the vast energy, transportation, and industrial infrastructure of more developed nations. In military terms, it lacked targets. Blown-up roads and bridges were rapidly repaired. Downed power lines were restrung. Destroyed power plants were replaced by thousands of small generators. Manufacturing plants were so small that destroying them was literally not worth the effort. In a classified briefing of US senators in the summer of 1967, McNamara explained that well over two thousand targets had been bombed in the North so far, and that of the fifty-seven identifiable ones that remained, none were significant enough to justify risking a pilot and plane, or even the cost of the bombs. One of the targets was a rubber plant that produced only thirty tires a day. Systematic bombing on the triple-canopy jungle that hid the bulk of North Vietnam’s armies was yielding an estimated mortality rate of only about 2 percent. And the cost was terrible. Well over nine hundred aircraft had been shot down over North Vietnam as of January 1968. Two hundred and fifty-five airmen had lost their lives and almost that many were now prisoners of war, held in brutal conditions. The cost-benefit analysis, the kind of thing McNamara did so well, was clear.

The failure of the air war was mysterious to those who had grown up proud of the world’s most powerful air force. Representative George Andrews of Alabama questioned one high-ranking military officer. As journalist Don Oberdorfer reported it:

“Do you have enough equipment?” asked the congressman.

“Yes, sir,” the officer responded.

“Do you have enough planes?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you have enough guns and ammunition?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, why can you not whip that little country of North Vietnam? What do you need to do it?”

“Targets—targets,” came the reply.30

On a trip to an aircraft carrier to thank and encourage some of the aviators flying these missions, LBJ was within earshot of a young flier complaining bitterly in a staff meeting. “We are going through the worst fucking flak in the history of man, and for what?” the pilot said, not knowing the president and his entourage were in the next room listening. “To knock out some twelve-foot wooden bridge they can build back a couple of hours later?”31

There were also profound human costs. An estimated one thousand North Vietnamese civilians were being killed or severely injured by American bombs every week. The carnage appalled the world. In a moving speech against the war in April 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Nobel Peace Prize recipient and a figure of towering international repute, branded his own country “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”32 Increasingly the United States found itself isolated. Having for two decades enjoyed its status as champion of the free world, it was increasingly the target of bitter criticism abroad and at home, where a growing number of prominent intellectuals and church leaders denounced the bombing campaign as barbaric. The military might disdain the fickle nature of public sympathy, but a democracy cannot sustain a war effort without it, and moral revulsion was growing.

In that memo to the president, McNamara firmly dispatched the bombs-away fantasy: “It is clear that, to bomb the North sufficiently to make a radical impact upon Hanoi’s political, economic, and social structure, would require an effort which we could make but which would not be stomached either by our own people or by world opinion; and it would involve a serious risk of drawing us into open war with China.”33

McNamara was dismissed by the president in late 1967—eased aside would be the more appropriate term. He was appointed to head the World Bank. In Johnson’s opinion, he had “gone soft.”34 The president dug in. As journalist Don Oberdorfer would write, “[He] took it personally. In private his critics were ‘simpletons,’ they were ‘cut-and-run people’ with ‘no guts.’” The war having commenced with the goal of stopping the spread of communism, there was no way LBJ was going to fall short of that promise. Despite McNamara’s convincing analysis, the bombing continued.35