Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In the sixty-four days between November 3 and January 6, President Donald Trump and his allies fought to reverse the outcome of the vote. Focusing on six states - Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin - Trump's supporters claimed widespread voter fraud. Caught up in this effort were scores of activists, lawyers, judges and state and local officials, among them Rohn Bishop, enthusiastic chairman of the Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, Republican Party, who would be branded a traitor for refusing to say his state's election was tainted, and Ruby Freeman, a part-time ballot counter in Atlanta who found herself accused of being a 'professional vote scammer' by the President. Working with a team of researchers and reporters, Mark Bowden and Matthew Teague uncover never-before-told accounts from the election officials fighting to do their jobs amid outlandish claims and threats to themselves, their colleagues and their families. The Steal is an engaging, in-depth report on what happened during those crucial nine weeks and a portrait of the heroic individuals who did their duty and stood firm against the unprecedented, sustained attack on the US election system and ensured that every legal vote was counted and the will of the people prevailed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 596

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

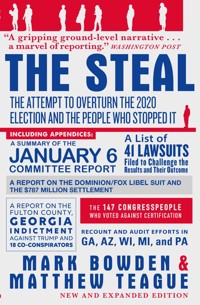

Praise for The Steal

“A gripping ground-level narrative of the weeks after Donald Trump lost the popular vote . . . The Steal is a marvel of reporting: tightly wound . . . but also panoramic.”

—Washington Post

“An indispensable and alarming ground-level record of how Donald Trump’s attempt to steal the 2020 election played out in precincts and ballot-counting centers in key states.”

—The Guardian

“A lean, fast-paced and important account of the chaotic final weeks.”

—New York Times

“The Steal is brilliant, an incredibly important document reported without bile or self-righteousness. A book every conservative should read.”

—P. J. O’Rourke, New York Timesbestselling author ofParliament of Whores

“It’s impossible to think of a better combination of writing and reporting talent to cover an historic assault on democracy than Mark Bowden and Matt Teague. That combination has produced a book that must be read now and will be read for many years to come. It is incredibly informative, terrifying and a screeching klaxon of alarm for our democracy. Imagine A.J. Liebling and William Shirer combining to write about the Reichstag fire of 1933 and that’s the sort of gift we—and history—have been given with The Steal.”

—Stuart Stevens, New York Times bestselling author of It Was All a Lie

“The Steal is a terrifying picture of the civil war that began on Election Day 2020. Here is the rancor, distrust, and deception that spun into the conspiracies and rabbit holes that Donald Trump has used to undermine truth, logic, and common sense. This is the behind-the-scenes world of the Big Lie. The Steal reads like an edge-of-your-seat political thriller—one without a happy ending.”

—Michael Wolff, New York Times bestselling author of Landslide

Comments on the 2020 Election

“The only way we can lose, in my opinion, is massive fraud.”

—Donald J. Trump at a rally in Allentown, Pennsylvania, on October 26, 2020

“And what Trump’s gonna do is just declare victory, right? He’s gonna declare victory. But that doesn’t mean he’s a winner. He’s just gonna say he’s a winner . . . The Democrats—more of our people vote early that count. Theirs vote in mail. And so they’re gonna have a natural disadvantage, and Trump’s going to take advantage of it—that’s our strategy. . . . So when you wake up Wednesday morning, it’s going to be a firestorm . . . If Biden’s winning, Trump is going to do some crazy shit.”

—Steve Bannon to a group of his associates in October 2020

“Vote counting is not a Republican or Democrat issue; everyone should want all the votes to be counted, whether they were mailed or cast in person. An accurate vote takes time. It’s possible the results you see now may change after all the votes are counted. This is evidence of democracy, not fraud.”

—Clint Hickman, Republican chairman of the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors, in a letter to Maricopa County voters on November 4, 2020, one day after Trump lost the election and claimed fraud

“Just to preempt the question, because I know it is going to come up: Are we seeing any widespread fraud? We are not.”

—Gabe Sterling, Chief Operating Officer for Brad Raffensperger, on November 6, 2020

“There is no fraud . . . Do you understand that you can suspect something, but it means nothing if you don’t have evidence . . . If you can find evidence, I’ll be the first person to thank you.”

—Valerie Biancaniello, Delaware County organizer for Trump, to Leah Hoopes and Greg Stenstrom on November 6, 2020

“It’s independent judges who are doing the fact-checking, and it ain’t pretty. . . . It’s harder to lie in court than, say, at a White House briefing. . . . Repeating things that other people say that aren’t true, maybe that gets you a retweet, but it doesn’t go far in court.”

—Ari Melber on MSNBC on November 12, 2020

“We were asked to take power we didn’t have. What would have been the cost if we had done so? Constitutional chaos and the loss of our integrity.”

—Aaron Van Langevelde, Republican vice chair of the Michigan State Board of Canvassers, in his statement certifying the results of the election on November 23, 2020

“I voted for you. I worked for you. I campaigned for you. I just won’t do anything illegal for you.”

—Rusty Bowers (R), then Arizona House Speaker, to Donald Trump on a phone call on December 25, 2020, during which Trump requested that Bowers unlawfully appoint presidential electors from Arizona

“Just say the election was corrupt + leave the rest to me and the R. congressmen.”

—Donald Trump to Rosen and his deputy, Richard P. Donoghue, in notes taken by Donoghue, on December 27, 2020

“President Trump . . . We don’t agree that you have won.”

—Brad Raffensperger, Georgia Secretary of State, on a phone call with Trump on January 2, 2021, when Trump said he wanted to “find 11,780 votes” in Georgia

“Will you please explain to me how this doesn’t create a slippery slope problem for all future presidential elections?”

—Senator Mike Lee on the fake electors plot, in a text message to one of Trump’s advisors on January 6, 2021

“Today was a dark day in the history of the US Capitol. Those who wreaked havoc in our Capitol today did not win. Violence never wins. Freedom wins. And this is still the people’s house. As we reconvene in this chamber, the world will once again witness the resilience and strength of our democracy, for even in the wake of unprecedented violence and vandalism at this Capitol, the elected representatives of the people of the United States have assembled again on the very same day to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. Let’s get back to work.”

—Mike Pence on January 6, 2021

“While the petitioners [Hoopes, Stenstrom, et al.] seek sanctions against the Board of Elections, they come before this court with unclean hands and they themselves are the ones whose conduct is contemptible.”

—Judge John Capuzzi on January 12, 2021, in his ruling on the lawsuit filed by Greg Stenstrom and Leah Hoopes in Delaware County, PA

“A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.”

—Donald Trump, in a post on Truth Social in December 2022

“The most obvious question in American politics today should be: why is the guy who committed treason just over two years ago allowed to run for president?”

—Robert Reich, former U.S. Secretary of Labor, in an Opinion piece in The Guardian on April 24, 2023

“Every fraud claim I was asked to investigate was false.”

—Ken Block, founder of Simpatico Software Systems, the second firm hired by Trump to investigate fraud, in an interview with the Washington Post on April 27, 2023

“The illegality of the plan was obvious. . . . Dr. Eastman and President Trump launched a campaign to overturn a democratic election, an action unprecedented in American history.”

—U.S. district judge David O. Carter of California, in his March 28, 2022, ruling on the release of emails between Trump and lawyer John Eastman

“It’s much bigger than Watergate. It’s of a whole different dimension. It goes to the very foundation of democracy.”

—John Dean, who served as White House counsel under Nixon and later became a key witness in Watergate, when asked on CNN whether he sees echoes of Watergate in the Trump case, on August 14, 2023

“I just think the [Republican] party is gone. . . . I don’t think there’s any way that it can be repaired. And I think Trump is going to take them down. . . . It’s like crack. I mean, they’ve addicted themselves to these lies. They live off of these lies. The conservative media profits off of these lies, the political consultants profit off of these lies. . . . The congressmen basically make a living selling lies to the American people for contributions and funding.”

—George Conway, conservative attorney, on the Bulwark podcast on August 8, 2023

“Trump and the other defendants charged in this Indictment refused to accept that Trump lost, and they knowingly and willfully joined a conspiracy to unlawfully change the outcome of the election in favor of Trump.”

—Georgia indictment filed in the Fulton County Superior Court on August 14, 2023

Also by Mark Bowden

Doctor Dealer

Bringing the Heat

Black Hawk Down

Killing Pablo

Finders Keepers

Road Work

Guests of the Ayatollah

The Best Game Ever

Worm

The Finish

The Three Battles of Wanat

Hue 1968

The Last Stone

The Case of the Vanishing Blonde

First published in the United States of America in 2022 by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2024 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © 2022, 2024 by Mark Bowden and Matthew Teague

The moral right of Mark Bowden and Matthew Teague to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 427 5

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 875 4

Printed in Great Britain

To the real patriots

Contents

Publisher’s Note

Preface

1 Election Day

2 The Count

3 The Blunderbuss Strategy

4 Pressure

5 The Popular Front

6 Epilogue

Afterword to the Paperback Edition of The Steal

Acknowledgments

Cast of Characters

Appendixes

A List of House Members Who Objected to Certifying the Electoral College Results

B List of Senators Who Objected to Certifying the Electoral College Results

C Guide to the Lawsuits Filed to Challenge the Election Results

D Recount and Audit Efforts

E The Report of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol: A Distillation

F The Dominion Settlement: Dominion Voting Systems vs. Fox News Network

G The Trump Indictment: U.S. v. Donald Trump

H The Georgia Indictment: Fulton County Superior Court vs. Donald Trump and 18 Co-Conspirators

Notes

Index

Publisher’s Note

The paperback edition of this book went to press on December, 22, 2023. By October 25, 2023, three codefendants had pleaded guilty in the Fulton County, Georgia, lawsuit against Donald Trump and eighteen others, but the trial had not begun. The special prosecutor lawsuit against Trump and four unnamed coconspirators is currently scheduled to begin in March 2024.

Preface

We began work on this book in April 2021 after some of the dust settled from the January 6 assault on the US Capitol. Donald Trump’s attempt to stay in power after losing the election was unprecedented in American history. It wasn’t clear in April that Congress was disposed to investigate it thoroughly—the House Select Committee on the January 6 Attack wasn’t formed until July. We set out to create a record of what had happened, specifically to tell the story of how Trump’s effort unfolded in each of the six most narrowly contested states. And we wanted to do it fast.

Then and now, most of the national media attention on the story focuses on Washington, on the efforts of Trump and his minions, and on the outrageous January 6 assault on Congress. That story continues to be aggressively pursued by law enforcement and by journalists, and recounted in the flood of tell-all books by former Trump administration officials. We believe that the less obvious and more important story happened in the swing states in the two months between Election Day and the violent assault on the Capitol by Trump’s mob.

With the help of a team of young journalists and researchers, we completed the book in just five months. Morgan Entrekin and his team at Grove Atlantic crashed it into publication in time for the first anniversary of the January 6 attack. For this paperback edition, we have revised portions of the text to incorporate new information that has surfaced especially from the work of the January 6th Committee, most significantly around the efforts to present “false electors” around the country.

We hope that The Steal helps document the wider scope of this seditious scheme and explains exactly how it played out in the counties and states where votes are tallied and certified. Trump and his inner circle were not the only ones trying to overturn the election. They had thousands of willing coconspirators across the country, lawyers, county and state lawmakers, election officials, and average citizens. And in each state, there were many who stood firm against this assault, who fought and in some cases paid a heavy price to defend democracy.

1

Election Day

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 2020

Donald Trump refused to believe he might lose. While some of his aides would tell him only what he wanted to hear, in the days before the election his own polling data said he would. Trump said no. He could feel it in his bones.

But . . . what if he lost? A man who grounds his very identity on winning has strategies for handling loss. For years, Trump had been laying out his. If the votes did not add up to victory, there was a reason. An obvious one. Everybody could see it. He had spelled it out again and again, warning even before his shocking victory in 2016 that the system was “totally rigged.”

Rigged by whom? Trump’s promise to “Drain the Swamp” was a sure applause line at his rallies. The expression long predated him, of course, referring to the nefarious ties between lawmakers and lobbyists, but Trump’s usage implied something more and kept enlarging. In time it became simply “The Swamp,” a thing he never clearly defined but that eventually seemed to encompass every entrenched institution in America. There was the “Deep State,” the career employees who made up the enduring machinery of government; the Democrat Party, stem and branch; unprincipled “career” politicians; the “lying” mainstream press; the technocrats who created and controlled the very internet platforms he and his supporters used; the Republicans who dared to criticize him; liberal academia . . . on and on the meaning expanded. Left-leaning and corrupt, The Swamp was an unyielding suck on Trump’s native genius, determined to drag him down, and with him the American dream.

Campaigning against Hillary Clinton, he had predicted “large-scale voter fraud” and had decried the American electoral process as fundamentally unfair. He forecast a sweeping crime capable of changing the nation’s course but was always vague about how it would actually work. Indeed, despite his claim that everybody knew it, there was no evidence of it in modern times. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that tabulated voting fraud cases nationwide going back more than thirty years, listed only widely scattered instances committed by members of both political parties, capable of influencing—and even then only in rare instances—local election results. But the charge resonated with those who feared big government, the growing number and power of minorities, the whole modern drift of American society. Drawing on antiquated stereotypes from the era of Tammany Hall, Trump especially stressed corruption in big cities, where Democrats ruled and the population was heavy with African Americans.

“They even want to try and rig the election at the polling booths, where so many cities are corrupt. And you see that,” he said, campaigning in Colorado in 2016. “And voter fraud is all too common. And then they criticize us for saying that. . . . Take a look at Philadelphia . . . take a look at Chicago, take a look at Saint Louis. Take a look at some of these cities where you see things happening that are horrendous.” In his final debate with Clinton, he had refused to say whether, in the event he lost, he would even acknowledge the results. In that event, the numbers would be crooked.

Even victory did not allay this gripe. He continued to throw shade on the contest, questioning the validity of Clinton’s winning margin in the popular vote, eventually setting up a commission to investigate voter fraud. Asked whether Clinton’s certified numbers were accurate, the commission chief, Kris Kobach, said, “We may never know the answer to that.” Even after the probe found nothing and disbanded, Trump continued grooming his supporters to expect fraud.

Throughout his White House tenure, he used his elevated platform to spread this message. In November 2018, prior to midterms, Trump and his attorney general, Jeff Sessions, warned of wide-scale voter fraud. They offered no evidence. Trump said, “Just take a look. All you have to do is go around, take a look at what’s happened over the years, and you’ll see. There are a lot of people—a lot of people—my opinion and based on proof—that try and get in illegally and actually vote illegally. So we just want to let them know that there will be prosecutions at the highest level.” As ballots were still being counted in Florida’s races for governor and US Senate, Trump claimed on Twitter, “Many ballots are missing or forged, ballots massively infected.” No evidence of this surfaced, no one was prosecuted, and both Republican candidates ultimately won.

Still he continued impugning the voting process. The move to allow more mail voting during the pandemic gave him a new target. “Mail ballots are a very dangerous thing for this country, because they’re [Democrats] cheaters,” he said at a coronavirus press briefing on April 7, 2020. “They go and collect them. They’re fraudulent in many cases. . . . You get thousands and thousands of people sitting in somebody’s living room, signing ballots all over the place.” Pressed the next day about the “thousands and thousands” claim, Trump promised to provide evidence, and did not. There wasn’t any. He wasn’t making a case; he was sowing suspicion.

So Trump did have a strategy in case of defeat. He used fear of fraud to raise millions of dollars for his 2020 campaign, soliciting contributions on his campaign website with the words “FRAUD like you’ve never seen,” asking for donations “to ensure we have the resources to protect the results and keep fighting even after Election Day.”

On October 26, one week before votes would be cast, campaigning in Allentown, Pennsylvania, he said, “The only way we can lose, in my opinion, is massive fraud.”

GEORGIA

In the darkness of election morning, the first drop of water fell from the lip of a urinal in an Atlanta bathroom, splashing onto a black concrete floor. Every flood arrives with a first drop.

For months, within the walls of the State Farm Arena, water had risen in a pipe that led to the bathroom in the Chick-fil-A Fan Zone on the upper level. The arena’s maintenance staff had shut off the water on that level during the coronavirus pandemic, since crowds couldn’t come watch the ice skating shows or listen to Harry Styles sing. But thanks to a valve not quite shut or an O-ring worn by time, water in the pipe inched upward. Sometime in early November, it topped a curved trap and began filling the basin of the urinal, a Toto Commercial model in Cotton porcelain.

Now it spilled into the world, pouring onto the floor, seeking the lowest point in concrete worn smooth by ten thousand pairs of sneakers. It seeped into crevices, into the arena’s structure and interstitial spaces, down through the wires and ductwork, and finally collected and poured through the ceiling of the room below.

About five thirty in the morning, a few blocks away at the county’s election headquarters, Rick Barron’s phone rang and chirped with the bad news. He was director of Fulton County’s elections, and stood surrounded by banks of phones and televisions. Workers back at the arena should have started sorting early ballots, but now calls and text messages said they hadn’t. When the first workers arrived, in the dark and quiet, they’d heard the impossible sound of what seemed like indoor rain. Someone flipped on the lights and the workers found themselves standing on the edge of a storm.

Now Barron watched a video of the indoor flood. The image showed a vast room, with an array of ballot-processing machinery, tables where the workers normally sat, and big plastic bins full of ballots. Two of the workers always made an impression, even in grainy arena security footage. Ruby Freeman stood out with an Afro that matched her big personality. In normal times she ran a kiosk at the mall selling handbags, socks, and other ladies’ accessories, which she called Lady Ruby’s Unique Treasures. But during election season she helped out with temporary work. Her daughter, thirty-six-year-old Shaye Moss, wore her hair in recognizable long blond braids, and had worked for years for the Fulton County elections office. Doing election work meant early mornings and long hours but it gave the mother and daughter a close-up view of democracy in action, right in the room where ballots were gathered, sorted, and counted. But now this—water pouring from above—had brought the machinery of freedom to a stop.

Behind his pandemic mask, Barron sighed. He would hear about this from higher-ups at the state level, which was the last thing he needed. He already didn’t fit in here; he was the only white member of his election staff, to start. And the Atlanta political class found him odd. He was from Oregon, for one thing. At that moment, he wore a lanyard emblazoned with the logo for the Portland soccer team, of all things. He might as well drink Pepsi.

Now a rain cloud had burst, somehow, in his counting room.

Bonkers, he thought. He showed the video to Johnny Kauffman, an Atlanta radio reporter who had covered local elections for years and had embedded with the Fulton County staff. It seemed funny, in a bleak way. “Oh my God,” Kauffman told him. “It looks like it’s raining from the ceiling.”

“It could only happen to us,” one of the election staffers said. What could Barron do but laugh?

He didn’t know he stood on a historic precipice; soon he would realize that in this election, any detail, no matter how small, could be manipulated. And any event, however mundane, could be contorted into conspiracy.

The downpour in the Atlanta arena turned out to be a brief squall. The arena’s maintenance crew found the source, fixed the urinal, and sopped up the mess. No ballots got wet; no equipment damaged. Shortly after eight, when the polls opened, the counting resumed.

Barron thought, No big deal.

PENNSYLVANIA

Proud, hopeful, and vigilant, Leah Hoopes arrived at her local polling place in Bethel Township before the doors opened. There was already a line. She had come not just to cast her vote for Donald Trump and the rest of the Republican slate but also to serve as a watchdog. She had formed a group by that name: the PA State Watchdogs. This was a fateful day for herself, her family, and her country.

The year before, Hoopes had been elected a Republican committeewoman in Bethel, in Delaware County, or Delco, as natives prefer, a sprawling suburb that stretches west and south of Philadelphia. Soon to be given a measure of fame by the fictional HBO series Mare of Easttown, it was home to more than half a million people, of whom only 9,500 lived in Bethel. The county contains disparate worlds, stretching from the city’s swanky, storied Main Line suburbs to the densely packed rows of blue-collar townhouses of Upper Darby. Bethel lay twenty-six miles southwest of Philadelphia at the Delaware border. The county was one of those traditionally red suburbs that in recent years began turning blue. In 2020, Delco had sworn in a Democratic majority on its governing council for the first time in a century and a half. But along the leafy curved lanes of Hoopes’s precinct, the vote still leaned Republican.

Hoopes is a slight and very energetic woman of early middle age, big-eyed, occasionally blond, cheerfully social—she loved a stiff drink—and fiercely opinionated. Trump had won only 37.4 percent of the vote in Delco four years earlier, but he had narrowly edged Hillary Clinton in Bethel. Two hundred and ninety-one votes had made the difference. Ever since, as best she could, Hoopes had rallied the Trump troops, mostly through pungent and frequent Facebook postings. She maintained two accounts, one featuring her face superimposed on an old tourist ad of a woman in a polka-dot spring dress with a red carnation in her hair, inside the slogan “Everyone Is Welcome on the Trump Train,” and the other with her in a Rosie the Riveter pose, with her hair tied in a red polka-dot kerchief, flexing her bicep over a “Trump-Pence” banner. Each had a following in the hundreds. She posted multiple times on most days, about, among other things, gun rights, the glory of God and America, Democratic perfidy, the necessity of cracking down hard on the leftist antifascist group called Antifa, and lately, vehemently, against all public health efforts to curb the COVID-19 pandemic, which she regarded as less threatening than the seasonal flu. For Hoopes, masks, vaccinations, and shutdowns were needless, and to the extent they were mandated or encouraged by government, liberal tyranny. When the statistics she posted to support her arguments were labeled false by Facebook, it just underscored her point. Mark Zuckerberg and the other social media titans, along with the mainstream liberal media and Demo cratic leaders, were out to push a liberal agenda, to stop Trump, and strangle freedom. Hoopes fought back with outrage and sarcasm. She was a cheerful and outspoken warrior, telling it like it was to anyone who would listen.

The term she self-applied was “patriot,” by which she meant something much more than showing the flag on Independence Day. And it wasn’t just a matter of degree. Her use of the word signified allegiance to a particular idea of America, one in tune with God, with the nation’s commonsense core—as these patriots saw it—where men were men and women were women, where justice meant protecting hearth and home and cherished values, where the heroic stories of American greatness learned in elementary school remained true, where folks lived and earned and thrived free of meddling government or so-called experts, where the old usually trumped the new, where gut feelings counted for more than science, where good people were free to carry guns to protect themselves from bad people, where America was respected worldwide and its power feared. As used more widely, the definition was loose by design and wasn’t always coherent. There were “patriots” who deplored racism and those who were white supremacists. There were those who both embraced America’s immigrant traditions but also wanted to build a wall to keep foreigners out. Some wanted to remove the United States from foreign entanglements but also wanted it to flex its muscles more aggressively overseas. The tent was wide. It included Christian fundamentalists and conspiracy theorists and ordinary God-fearing, gun-toting wives and mothers like Leah Hoopes. But all shared a conviction that the America they revered lay under siege. The “patriot” stood armed and ready at a conceptual Bunker Hill, holding the line against the erosion of faith and decency, against big government, multiculturalization, affirmative action, or any other force that threatened their traditional ideal, or to abolish freedoms in the name of some cockeyed communal purpose. This especially included repressive, expensive, harebrained programs and policies to reengineer America, like those to redress “institutional” racism and sexism, to confuse the concept of gender, to enforce safety and health regulations in the name of public safety. “Patriots” recognized each other. It was less an ideology than a feeling.

And Donald Trump got it. Hoopes had been sold on him since the moment he descended the escalator in his Manhattan tower on June 16, 2015, to declare his candidacy for president. Here she saw a powerful, savvy messenger for those like her, who felt America lazily slipping away from greatness. The eight years of Democratic governance under President Barack Obama had been one tortuous disaster, with elitist nannystate policies supplanting sensible tradition and good old-fashioned patriotism replaced by self-hatred. Trump understood it all. He waged war against apologetic Americans who held a jaundiced view of their own country, who saw it as flawed, racist, and in need of improvement, who had rendered it impotent, unwilling to carry a big stick abroad and incapable of policing its cities and borders. Trump had the guts to call out immigrants as drug dealers and rapists—not all of them, of course, but those who were tearing at the fabric of the country. His words infuriated the lefties, which is what she liked about him particularly. He never apologized, and he didn’t mince words.

Not that she was starry-eyed. A lot about him made her cringe. He had a huge ego. He was often crass. But he saw America as she did: as the hope of the world. It was still the place millions envied and yearned to live in, which was fine, so long as they arrived legally. Some of Hoopes’s dearest friends were immigrants. But through three years and more in the White House, Trump had withstood relentless liberal persecution and mainstream media assaults as he fought for her and other patriots to restore the unabashed, righteous, proud image of Amer i ca they held dear.

So the consequences on this Election Day were, as President Trump would say, huge. He simply could not lose to Biden, whom she called a “stuttering prick.” The cost would be catastrophic. As her Facebook writing made clear, Hoopes regarded Democrats less as fellow citizens with whom she disagreed than as a threat to the very idea of Amer i ca, out to destroy her way of life. Weeks earlier, after a discussion with her husband, Zach, she posted a plea for her fellow patriots to rise up as if it were 1776. She spelled out the consequences of a Democratic win: “Our business will cease to exist . . . the luxuries we have will no longer exist, our freedoms diminished, our opportunities gone, our schools have crumbled, the middle class will no longer exist.” Rioting and looting in the cities would spread to their own quiet neighborhoods; in fact, she wrote, “It is the goal of the left to destroy suburbia.” Only thirty-five people liked her post, which illustrated the challenge. But Hoopes would reach a much bigger audience soon enough.

The truth is that ardent Trumpists like her were outsiders, even with the local Republican Party. Delco’s GOP organization viewed them the way mainstream churches viewed evangelicals. They shared the same religion but not the same zeal. Trump rallies filled Hoopes with exhilarating passion. At them, she felt engulfed in fellowship, immersed in a rising, egalitarian, class- and color-blind tide of those who believed America was pretty near perfect exactly as it was and had been. Trump had beaten the staid old Republican guard, who had failed to grasp the urgency of the moment. This passion was a big reason she had gotten herself elected as committeewoman and had scored her pass as an official poll watcher. As Election Day approached, Hoopes believed that Trump and the patriot tide were unstoppable . . . unless something happened. Unless the Democrats cheated.

Trump had asked them to prepare. He wanted them to monitor their polling places closely. The PA Watchdogs existed, in her words, to “expose and bring to light election fraud.” They linked themselves with the Thomas More Society, an activist Chicago-based law firm that figured prominently in Trump’s effort to challenge voting procedures. Hoopes had joined an October lawsuit by the organization attempting, without success, to bar districts from accepting grants from the Center for Tech and Civic Life, a philanthropic organization partly supported by donations from Zuckerberg. Delco had used one such grant to purchase new vote-counting machines for the anticipated flood of mail ballots—the pandemic would prompt millions to cast their ballots in advance from home. When she met Greg Stenstrom, a navy veteran who presented himself as a “data forensic scientist,” she recruited him, telling him, “I could use some help if somebody knows fraud.” Neither he nor Hoopes had ever worked on or observed an election, but they planned to pay close attention and make a public record of what they expected to find. In one of her posts, she had called the Demo crats on the county council and election board, her county neighbors, “lying hacks.”

Here was the animating principle behind Hoopes’s concern. The Demo crats who had won Delco in 2019, those at the state capitol at Harrisburg, those walking the federal halls of Washington, DC, and those embedded throughout all levels of government bureaucracy, the Deep State—along with their allies in the party’s mainstream, in academia, and the press—were not simply fellow citizens with competing views. They were subversives. Anti-Americans. They could not be trusted to run a fair election.

Plenty of fervent Democrats had a similar way of looking at Republicans. They were racist, ignorant, xenophobic, and determined to impede the popular vote. This Election Day felt more like combat than friendly competition. A day of pent-up emotion.

So Hoopes arrived early and keen-eyed at Bethel’s Precinct 5 polling place, the Belmont Community Club House, a low, tan building in a tony village for the elderly wrapped around a shallow pond. It was about as placid a location as you could imagine. But the atmosphere felt charged. Feelings were running high. Hoopes knew many of the poll workers and voters. Quite a few were seniors. They were afraid of catching the COVID virus and afraid they might encounter violence. Trump’s son Donald Jr. had called for an “army” of Trump supporters to show up at polling places around the country.

“The radical left are laying the groundwork to steal this election from my father,” he said. “We need every able-bodied man, woman, to join [the] army for Trump’s election security operation . . . we need you to help us watch them, not just on Election Day, but also during early voting and at the counting boards.”

So the mood, even in quiet Bethel, felt tense. The lines Hoopes saw on arrival persisted throughout the day. They fed into a large well-lit conference hall, with long tables to one side manned by poll workers. Voters were checked against the registration books and directed to curtained pods to cast their votes. Hoopes tried to keep things calm, and the Democratic poll watchers seemed composed and professional. She directed people and looked for ways to be helpful.

Problems started right away, though. The voting machines Delco had purchased to record ballots were new. Voters marked paper ballots, which the machines then scanned. The process created an electronic image of the ballot, stored in the machine’s memory and backed up by the paper copy. The machines, provided by Hart InterCivic, had been the subject of a misinformation campaign two years earlier, in Texas, that suggested they might be used to switch votes. Texas secretary of state Rolando Pablos had felt the need to issue a statement defending them. They were originally designed for votes to be cast on an electronic slate, but out of continued worry about vote-switching, they had been redesigned to accommodate a paper ballot, so there would be a physical record. Because of the pandemic, most Delco poll workers had not received in-person training on the new machines. Either because of human error or some issue with the batch they had been given, the paper ballots kept jamming, which meant each had to be discarded and the voter asked to fill out another. This slowed the flow and kept the lines long.

One of the county’s roving repair vans arrived that morning to take a look and diagnosed a paper problem, not a machine problem. A fresh batch of paper ballots was delivered, but Hoopes saw little improvement. It seemed fishy to her. It looked more like incompetence than outright fraud, but what if the clumsiness was deliberate? Considering the narrow margin Bethel had given Trump over Hillary Clinton, she wondered if the Democrats now in charge had intentionally provided clunky machines and hapless operators to her precinct to gum up the works. The idea grew. She would later liken it to a “Nazi operation,” with “little monkeys” following orders after being set up by their superiors to fail.

Across Pennsylvania, millions voted that day without incident, but some, as always, encountered problems. Voting is a complicated and highly decentralized process with many people, machines, and procedures, all of them working quickly. There were new machines in many counties, and the pandemic had created a host of new rules, often irregularly enforced. So there were screw-ups, delays, and, in many places, confusion. Urged on by their candidate, Trump voters and observers stayed attentive.

Gary Phelman, a rare Republican voter in Philadelphia, had a gold slip of paper that he believed authorized him to watch the voting on behalf of Trump at any polling place in the city. When he heard a rumor that observers like him were being turned away at a polling place in South Philly, he drove there. It was a funeral parlor. He entered and was asked to leave. He showed his gold certificate.

“That’s not good here,” a poll worker told him.

“It is!” he insisted and asked her to read it.

They stepped outside, and Phelman’s friend videoed the exchange.

“I’m the eyes and ears of the president of the United States,” Phelman said. He was gently turned away.

Barbara Sulitka, an elderly Trump voter in Fairview Township in rural central Pennsylvania, voted for the president, but when she received a printout, it confused her. She did not see his name on the slip of paper. She complained to a poll worker who assured her that her vote had been recorded, but she remained concerned that the names for the presidential slate didn’t appear on the printout. She was told that this was to protect the secrecy of her ballot, but she stayed worried. Had they counted her votes?

Another Trump voter from Drums, a township in central Pennsylvania, was confused by how to use the new machines and wasn’t sure his ballot had been scanned. He found the poll workers unhelpful. Olivia Jane Winters of Philadelphia found confusion at her polling place over voters who showed up with mail ballots they had not filled out. She felt the workers there had been rude to her when she complained that some of those people might be voting twice. There was no evidence that any had.

There were plenty of incidents like these. In an ordinary election, they might result in an angry letter to a precinct captain. But this year, they, like the leaky urinal in Atlanta, were all going to become a big deal.

Hoopes stayed all day at her polling place in Bethel, happy to participate and only mildly concerned by what she had seen. She left shortly before the polls closed at eight that evening in order to witness the sealing of the township’s ballot drop box. By law, the box had to be secured when the polls closed. She watched that happen and then drove to the nearby McKenzie Brew House to celebrate with her fellow Watchdogs.

They were thrilled by the early returns strongly in favor of Trump and other Republican candidates. In her precinct alone, Trump had received 67 percent of the in-person votes tallied so far. Her own candidate for the state legislature, Craig Williams, was also winning handily. The first sign of trouble came in a call she took from her fellow poll watcher Greg Stenstrom.

He said there were big problems at the counting center.

MICHIGAN

Antrim County, Michigan, seemed an unlikely setting for the attempted overthrow of an American election.

In the mitten shape of the state’s lower peninsula, Antrim makes up a fingertip in the far north. It sits on the eastern side of Grand Traverse Bay, which took its name from French voyagers who in the eighteenth century paddled canoes across its lonesome width: la grand traverse, they called it.

About twenty-three thousand people live in Antrim. Many work in fruit production, including the cherry farms that make the region the “cherry capital of the world.” They grow sweet cherries and sour: Montmorency cherries, Balaton tart cherries. Cavaliers, Sams, Emperor Francises, Golds, and a particular local favorite, Ulsters.

In spring, those cherry trees cover the landscape with pink and white blossoms. And the county features what people here call the chain of lakes, a series of fourteen terraced lakes and rivers starting with Beals Lake at the top and finally flowing into the Grand Traverse. The largest and deepest body in the chain is Torch Lake, where long ago Native Americans fished by torchlight. Today Antrim’s residents sail their boats up and down its length on turquoise waters.

So Antrim County sits on a peninsular outcrop, its people are few and scattered, and its landscape is sublime. All of which makes it seem outlandish as the stage for what followed: private jets arriving in the night, intrigue, threats of violence, and an effort to subvert the will of the American people.

Election Day started with coffee for Sheryl Guy. She poured it from the old Bunn coffeepot into her teal-colored mug. Then she placed a lid on the mug, because you never know what might go wrong.

Life had carried the Antrim county clerk toward this moment since her first breath in a sense. In a concrete-block room, here in the Antrim County Building, her own birth certificate sits in a chunky black binder: Baby Sheryl Ann, born May 1961, eight pounds and ten ounces.

She graduated from the local high school on a Friday, and the next Monday she started work in the county building as a receptionist. She worked her way up and sat in every chair in the building along the way: clerk 1 and 2, deputy 1 and 2, chief deputy, administrator. For thirty-one years she worked under the previous county clerk, whom she viewed as a mother figure and who granted Sheryl—maiden name Kirts then—a license to marry her high school sweetheart, Alan.

Now Guy was almost sixty and county clerk herself. The people of Antrim had elected her for the job eight years earlier, and she loved it. It’s a small county, so on Election Day she and her staff of four handled election duties along with the everyday responsibilities: collecting court fees, paying the county’s bills, certifying births and marriages. “Busy,” she said.

The vote itself went smoothly. Michigan counties are divided into grid-like townships, which are home to what they call villages: Elk Rapids village, Central Lake village, and so forth. People across the county voted on issues specific to their villages—on school boards, on a proposed marijuana shop—and bigger questions like the US presidency. There was a last-minute change, adding a candidate for village trustee to the ballot, but people voted without confusion or incident. Guy voted to reelect both Trump and herself.

Poll workers in precincts around Antrim fed people’s ballots into scanners, which printed out tally tapes that looked like thirty-foot strips of receipt paper. The scanners also recorded the votes on memory cards.

At about 6:00 p.m., Guy walked from the county building to buy dinner for the staff—“the girls”—at Short’s, a pub that sells sandwiches with names like “Sketches of Winkle” (salami) and “Old Man Thunder” (braised beef). They worked while they ate, and after the polls closed the results started to come in. Poll supervisors from around the county brought their memory cards to Guy at the county office, and she plugged those results into her central computer. It placed the votes into what amounted to a spreadsheet, sorting about sixteen thousand votes into columns and rows.

It took hours. Guy is quick to admit she’s not technologically adept. “I’m not a techie person,” she said. “I type, and I use my computer when I have to.”

They finished just before 5:00 a.m., in total exhaustion. Guy had spent hour after hour peering at the columns and rows and, by the end, was too tired to step back, figuratively, and consider a broader view of the election. She knew she, a Republican, had won reelection as county clerk because she ran unopposed. But she felt too weary to even note how many votes she got. She registered, vaguely, that Joe Biden had won the presidential vote.

She locked the office about 5:00 a.m. and headed home briefly to shower. No time for sleep. She said a brief good morning to Alan, a machinist, then gave him a goodbye peck and drove back toward her office. Along the way she stopped at McDonald’s to buy breakfast for the girls, who wanted sausage and egg McMuffins. Between placing her order and arriving at the pickup window, she received an email from an earlyrising citizen who had seen reports of the presidential vote in Antrim. The short message was ominous: “Things don’t look right.”

The results she had posted, unofficially, showed Joe Biden beating Donald Trump by about 3,200 votes, which would be nearly impossible in a county as reliably Republican as Antrim. That kind of sudden shift in long-standing voting patterns signaled a problem, and the realization awoke Guy like a shock of cold water. “Oh CROW,” she cried. She wanted to race to the office but could only sit trapped in the drive-through. Finally, after picking up the McMuffins, she gunned her car toward the county building.

She quickly put out a statement on Antrim’s official Facebook page. “By this afternoon, we expect to have a clear answer and a clear plan of action addressing any issue,” she said. “Until then, we are asking all interested parties to bear with us while we get to the bottom of this.”

That sounded confident enough, but inwardly she felt baffled. What could’ve happened? She suspected a culprit: computers. They probably weren’t talking to each other right. So all day, she and her staff totaled up votes directly from the official tape printed at each precinct and entered that by hand into the central computer. Then they republished the results, which now showed Trump as victor.

But a new problem arose. Now the totals showed more than eighteen thousand votes, which was two thousand too many. And the world was starting to notice tiny Antrim County.

CROW.

ARIZONA

Lynie Stone didn’t like to vote. She didn’t trust it.

Four years earlier, she had instead prayed and meditated, and set an intention that Donald Trump would win, which had worked! But this year, she had changed her mind, not about Trump—she liked him—but about her role.

“I’m voting in this election,” she told her husband. This admirable, civic-minded decision would lead her down a trail of disillusion, to a public stand on a national stage.

A mail ballot wouldn’t do. A voice inside her told her that she needed to vote in person and early, and Stone listened to her inner voice. So a week before Election Day, she drove from the ranch she and her husband owned outside Tucson to the modernist Pima County Recorder’s Office, a big white-and-black box with five stone pillars in front that appears to have been designed to look like a giant computer component. She brought her passport and driver’s license. Arizona law required only one photo ID, but Stone was on a mission.

An animal chiropractor, she looked like someone who just stepped off a ranch, with sun-bleached long brownish-blond hair and a pink complexion that looked mildly baked. Her sunny mood clashed immediately with the hushed gloom of the office.

“I’m here to vote,” she told the clerk, an older man, seated behind the front desk.

He just smiled.

She told him that she had brought her IDs, and he thanked her but didn’t seem to care. The look on his face and his tone implied they weren’t necessary, which she found odd.

She was given a ballot and made a mistake filling it out. She offered to take it home and shred it.

“Oh, no, no, no,” he said. “You can’t do that.”

The clerk drew lines with a black marker through her votes and wrote “SPOILED” on both sides.

“This ballot has to be accounted for,” he explained. She watched as it was placed in a box with others marked the same. Then they gave her a new one, which she filled in correctly, voting for Trump and others. She signed it and sealed it in an envelope. It was placed in a locked box with other ballots. Then she received a slip of paper with a website printed on it—Pima.gov/VoteSafe—where she could, in three days, track the processing of her vote online.

On her way out, she noticed that there was a drive-up ballot collection window, which struck her as inappropriate. You could vote the way you picked up a burger and fries? She didn’t see photo IDs being checked nor the ballots themselves. What if these drive-up voters made a mistake, too? Was there a “spoiled” box for them? She left the center with an uneasy feeling.

Stone waited three days and then accessed the website to check on the status of her ballot. She downloaded a three-page Excel spreadsheet. This would lead her down a complex path that others might find hard to follow.

The recorder’s office had assigned her ballot to a batch labeled “Q2.” At that point, the numbers for this batch listed thirty-nine duplicated ballots but no rejected ballots. This worried her. In fact, hers had been counted as “duplicated” because she had been handed a duplicate after she’d made the mistake. “Rejected” ballots were ones with mistakes where the voter was unavailable to fill out a new one. She didn’t understand the difference and so was confused enough to wonder why her “spoiled” ballot hadn’t been counted as “rejected.” If that spoiled ballot had not been counted, had her corrected one?

She called the recorder’s office and failed to get a satisfactory answer. The person she spoke to didn’t seem to grasp the nub of her confusion. “What are you saying?” he kept asking and left her with the classic bureaucratic brush-off “We’ll have to study that.”

This sent Stone back to the spreadsheets, which only grew more worrisome. Out of 454,633 total ballots—she was now looking beyond her batch—only 20 were listed as “rejected.” This seemed way too few. Given her understanding, she wondered how it was that more people, like her, hadn’t made mistakes on their first try. The spoiled ballots of those who had were, like hers, noted in the category “duplicated,” but she hadn’t made that connection. If she had, she would have discovered that she was right about the number of voters who made errors. And each day, as more votes were cast, they grew more numerous. There were now more than forty “duplicated” ballots in her Q2 batch alone.

When the votes were all in, something caught her eye about that “duplicated” column that chilled her. The total of “duplicated” ballots countywide was 6,660. The number 666 is, in the Book of Revelation, the “sign of the beast,” the mark of the Antichrist. Stone followed QAnon, the conspiracy theory that posited an international group of Satanic pedophilic sex traffickers as the secret power behind forces fighting Trump. And here was Satan’s signature, right there in the county’s spreadsheets! The Pima County vote was not just fraudulent, but evil.

On election night, she was watching TV with her dogs when Fox News called her state for Biden. This was just minutes after the polls closed.

It made Stone’s blood boil. She knew what was happening!

Was she the only one seeing this?

COOPED

Across the country, a handful of Americans had arrived first at a new and precarious place: a historic ridge dividing the way elections worked before and the way they would work after.

To survey America’s electoral record is to look back on a landscape of these ridges, for better and worse. The millions of followers who applauded Trump’s declarations of fraud seemed unaware how long and hard the country had struggled to refine the vote. Some failures and victories loom so large they barely need naming; women gained suffrage only in 1920, for instance, and many African Americans won real access to polls only after the civil rights acts of the 1960s. But the history of voter fraud, in particular, describes two general styles.

In the first, broadly, perpetrators tried to sneak phony votes into the ballot box. During the “political machine” era of the 1800s, for instance, parties printed their own ballots and stuffed collection boxes. Even less subtly, political bosses sent thugs into polling places to beat up any voter not holding the right-colored ballot. In New York City, the Society of St. Tammany—Tammany Hall—instructed its followers to grow full beards before voting on Election Day. Later in the morning they shaved their beards into mutton chops and voted a second time, then shaved down to moustaches and voted again.

Tammany Hall and similar outfits in other cities “cooped” voters by throwing enormous parties with free booze in their locked basements a day before elections or by kidnapping victims outright. Then on Election Day they hauled their half-conscious captives to the polls, often forcing them to change clothes and vote multiple times, between which the victims either took more alcohol or beatings. Some scholars theorize the author Edgar Allan Poe died a victim of cooping; Baltimore reeked of voter fraud in 1849, and on Election Day a man discovered Poe semiconscious at a tavern that also served as a polling place where coopers often brought their victims. Instead of his own clothes, Poe wore an ill-fitting farmer’s outfit, including a straw hat. Poe gave the concerned man the name of a magazine editor who also was a doctor, so the man quickly dispatched a handwritten note—

Baltimore City, Oct. 3, 1849

Dear Sir,

There is a gentleman, rather the worse for wear, at Ryan’s 4th ward polls, who goes under the cognomen of Edgar A. Poe, and who appears in great distress, & he says he is acquainted with you, he is in need of immediate assistance.

Yours, in haste,

JOS. W. WALKER

To Dr. J. E. Snodgrass.

—but too late to save Poe.

So there was a colorful history of this style of fraud, but the nation had prevailed against it, mostly with simple innovations. Colored ballots, for instance, gave way to secret ballots around the turn of the twentieth century, state by state; once voters stepped behind a curtain, political bosses’ bribes and threats became useless. Nobody knew how they’d voted. States set boundaries at polling places to restrict electioneering that could intimidate voters. And in recent years, more sophisticated technologies have allowed election officials to sift mountains of data to search for patterns of illegal votes across entire populations. These safeguards so thoroughly snuffed out illicit voting that in the weeks after the 2016 election, when the Washington Post combed legal records searching for confirmed cases of fraudulent presidential votes, the paper found exactly three: a woman in Iowa voted twice for Donald Trump, a man in Texas voted twice for Trump, and a woman in Illinois tried to vote for Trump on behalf of her dead husband. A fourth case involved a local mayoral race. None of those votes were counted. Others almost certainly went undetected, and authorities may have discovered straggling cases later, but the report made Trump’s claims—ballot boxes stuffed with millions of illegal votes—a farce.

In the second style of voter fraud, culprits tried to keep legitimate votes out of the ballot box. For instance, southern authorities suppressed votes with ham-fisted rules like land ownership requirements, poll taxes, and literacy tests. A more insidious technique raised the specter of the first style of voter fraud—ballot stuffing, dead voters, and so forth—even when there was none. In this case, politicians often played on their constituents’ fear of outsiders who threatened to snatch away control of the country. In the 1840s, for instance, a political cartoon showed an Irish immigrant dressed in a whiskey barrel and a German immigrant wearing a beer keg, stealing an American ballot box. Such propaganda stirred nativist sentiment and gave politicians a pretext for restrictive voter laws. More recently, as technology extinguished the first style of election fraud, the technology itself became seen as a vulnerability. Could foreign hackers meddle with the count?

The human suspicion that there’s something funny going on here is universal. The US Constitution delegates the responsibility for handling elections to the states, where a patchwork of party loyalties defines America’s political map, and modern politicians, both left and right, have alleged voter fraud with varying degrees of credibility.

In 1960, Republicans claimed that corrupt political bosses in Cook County, Illinois—Chicago—handed a narrow victory in the state to John F. Kennedy over Richard Nixon. Historians have since analyzed the vote and concluded that yes, corrupt counting favored Kennedy, but no, it didn’t decide the race in Illinois. At the time, Nixon didn’t know that, of course. Even so he, one of the shrewdest and most grasping of all American politicians, declined to object to the outcome. He conceded to Kennedy and told a friend, “Our country cannot afford the agony of a constitutional crisis.”

After the presidential election of 2004, some Demo crats expressed suspicion that voting machines in Ohio may have tilted the vote there toward George W. Bush over John Kerry. The New York Times said otherwise, in an editorial: “There is no evidence of vote theft or errors on a large scale.” The Washington Post dismissed the claims as “conspiracy theories.”

Even so, Demo cratic US representative John Conyers, then ranking minority member of the House Judiciary Committee, led an investigation into irregularities in Ohio and issued a report called Preserving Democracy: What Went Wrong in Ohio. The report accused then-secretary of state Kenneth Blackwell of using his position to purge voter rolls of minority citizens who hadn’t voted recently, and detailed various computer irregularities, but didn’t offer evidence of mass fraud.

The left-leaning magazine Mother Jones, in a closer investigation of its own, found that, yes, Ohio politicians had used their authority to influence the election, but no, it didn’t add up to fraud. Even so, the next year Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took up the cause, writing in Rolling Stone of a “media blackout” and that “indications continued to emerge that something deeply troubling had taken place in 2004”—language that would later become recognizable from the other side of the political aisle. But in Salon, Farhad Manjoo dissected Kennedy’s case, saying “the evidence he cites isn’t new and his argument is filled with distortions and blatant omissions.” Further: “If you do read Kennedy’s article, be prepared to machete your way through numerous errors of interpretation and his deliberate omission of key bits of data.”

None of the squabbling on the left mattered, though. After the election, a spokesman for the Democratic Party had said, “The simple fact of the matter is that Republicans received more votes than Democrats, and we’re not contesting this election.” And Kerry, to the point, had conceded to Bush.

In May 2017, Trump created a commission headed by Vice President Mike Pence and Kansas secretary of state Kris Kobach, who would hunt down evidence of the fraud Trump had claimed. The clear message was, Now that I’m president, we can finally get to the bottom of this. The probe ended a little more than a year later, without documenting a single instance. One of the commission’s own members, Maine secretary of state Matt Dunlap, attacked it, saying it had “a pre-ordained outcome,” which it could not deliver. A draft of its unissued report listed categories of election deceit, but the spaces for documentation were, according to Dunlap, “glaringly empty.”

“It was a dishonest effort from the very beginning,” said Dunlap in an interview with journalist David Daley. “It was never really meant to uncover anything. It was meant to backfill an unprovable thesis that there’s voter fraud—then to issue a fake report justifying laws or executive orders that change the fundamental nature of how we run elections. I think that might have been the real danger that we averted.”