Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Sandtown is one of the deadliest neighbourhoods in the world; it earned Baltimore its nickname Bodymore, Murderland, and was made notorious by 'The Wire.' Drug deals dominate street corners and ruthless, casual violence abounds. Montana Barronette grew up in the centre of it all. The leader of the gang 'Trained to Go,' or TTG, when he was finally arrested, he had been nicknamed 'Baltimore's Number One Trigger Puller.' Under Tana's reign, TTG dominated Sandtown. When a string of murders were linked to TTG, each with dozens of witnesses too intimidated to testify, three detectives set out to put Tana in prison for life. For them, this was never about drugs: It was about serial murder. Acclaimed journalist Mark Bowden, who spent his youth in the white suburbs of Baltimore, returns to the city with exclusive access to the FBI files and unprecedented insight into one of the city's deadliest gangs and its notorious leader. As he traces the rise and fall of TTG, Bowden uses wiretaps, police interviews, trial transcripts and his own ongoing conversations with Tana's family and community to create the most in-depth account of an inner-city gang ever written. With his signature precision and propulsive narrative, Mark Bowden positions Tana - as a boy, a gang leader, a killer, and now a prisoner - in the context of Baltimore and America, illuminating his path for what it really was: a life sentence.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 474

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for

LIFE SENTENCE

‘A ground level view . . . The masterful yarn is a riveting true narrative about an FBI investigation that landed eight criminal bosses behind bars in the city profiled in the popular American television crime drama The Wire’

—Associated Press

‘Most of the TTG gang members are now serving life sentences, but as Bowden starkly illustrates, neutralizing one criminal enterprise won’t solve the great ongoing tragedy of violence in poor, isolated urban Black communities, nor will it fix the devastation fuelled by racist policies from the 19th and 20th centuries’

—Washington Post

‘A scorching true-crime narrative . . . Bowden pulls no punches in his indictment of the ways in which the richest country in the world has allowed Black children for decades to be born into blighted urban neighbourhoods, and saddled them with burdens that they must struggle to surmount to lead meaningful lives. This account of “young men growing up in a place where murderous violence has become a way of life” will haunt readers long after they finish it’

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

‘Bowden turns his masterful storytelling talent to chronicling the gang’s reign of terror and law enforcement’s Herculean efforts to end it . . . A powerful chronicle of gang life. Life Sentence is not pessimistic, despite the hopelessness at the heart of its story. Instead, it offers many avenues for change and improvement if only the proper political will can be summoned and applied’

—Booklist

Also by Mark Bowden

Doctor Dealer

Bringing the Heat

Black Hawk Down

Killing Pablo

Finders Keepers

Road Work

Guests of the Ayatollah

The Best Game Ever

Worm

The Finish

The Three Battles of Wanat

Hue 1968

The Last Stone

The Case of the Vanishing Blonde

The Steal

First published in the United States of America in 2023 by Grove Atlantic

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2024 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Mark Bowden, 2023

The moral right of Mark Bowden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Photo credits are as follows: p. 1: Courtesy of Shanika Sivells; p. 16: Baltimore Police Department; p. 33: Maryland Historical Society; p. 50: YGG Tay, “My City;” p. 82: Wikimedia Commons; p. 103: Courtesy of Joe Landsman; p. 128: Courtesy of Ronnie Johnson; p. 145: The Baltimore Sun; p. 172: Courtesy of Joe Landsman; p. 192: Baltimore Police Department; p. 215: Courtesy of Mark Neptune; p. 227: Baltimore Police Department.

“Trained to Go (TTG).” Words and music by Baby Bomb, Lamar Joseph, Juaqui Malphurs, Karim Kharbouch, Lex Lugar, Joe Moses and Omar Maurice Ray © 2010 Kimani Music, Juaquinmalphurspublishing, Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp., WC Music Corp., BMG Rights Management (US) LLC and The Administration MP Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission of Alfred Music.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 80471 041 8

E-book ISBN 978 1 80471 040 1

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Stan Heuisler, who gave me a shot

Contents

Preface

1 The Game (or, The Greased Path)

2 Shabangbang Shaboing

3 The Fulton Avenue Wall

4 Either You Got to Be That, or You Ain’t

5 Shit Be Catching Up with Them

6 Here Come Landsman

7 The Ballad of Ronnie Jackass

8 We Hunting

9 Number One Trigger Puller

10 Gotta Take It on the Chin

11 Drinking from a Fire Hose

12 What Are We Supposed to Do Now, Clap?

13 Crabs in a Bucket

Notes

Books

Acknowledgments

So that in the nature of man, we find three principall causes of quarrel. First, Competition; Secondly, Diffidence [self-defense]; Thirdly, Glory. The first maketh men invade for Gain; the second, for safety, and the third, for Reputation . . . for trifles . . .

— Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

Preface

This book began early in 2021, with an invitation from the US Attorney’s office in Baltimore, which was eager to talk about its efforts to combat that city’s shocking street violence. The prosecutors I met were rightly proud of the work they were doing to take violent gangs off the street, and I assumed they had invited me in hopes that I might write something about it.

They did have a good story to tell, and when I asked them for a specific example, they told me about Trained to Go, a Sandtown gang run by a young man with the unlikely name Montana Barronette. The gang, mostly teenagers, had terrorized its West Baltimore community throughout the previous decade. TTG had been linked to twenty or more killings and convicted and sentenced, as a group, for ten of them. It was a rich opportunity. I knew that the story of how TTG was investigated, arrested, and prosecuted would be fascinating in itself, and journalists rarely get such willing cooperation from law enforcement, especially federal agencies. But what interested me more was a bigger and more important story.

Who was this Montana Barronette? How did he become who he became—a young man, barely out of his teens, known to the Baltimore police as the city’s “number one trigger puller”? I had started my career as a reporter in Baltimore. One of the first major stories I wrote was a series about life in a West Baltimore high-rise housing project, which I lived in, off and on, for a week. I was familiar with Barronette’s home turf of Sandtown. It had long been considered one of the worst neighborhoods in the city, an exemplar of intractable urban failure and neglect. It was the backdrop for much of David Simon’s series The Wire, which had begun airing almost twenty years earlier. Why was it still that way? Why was it so seemingly impossible to change? These questions were bigger than the specifics of this story. There were neighborhoods and characters like Sandtown and Barronette in cities all over America, where rates of homicidal violence are an ongoing national disgrace.

So I set out to find answers, framing this book chapter by chapter as part of the larger story. There was Barronette’s greased path into drug dealing and murder, starting with his family and childhood circumstances, which pulled him in a direction that would have been hard to resist—even though most young men born in such circumstances do. There was the long racist history of Baltimore itself, the intentionality with which Sandtown was created. That long story intersected with my own upbringing as part of the privileged baby-boomer white caste in the city’s northern suburbs, just ten miles by map but in all other respects a whole world away. I looked into the ambitious, expensive, and ultimately futile effort in the first decades of this century to rebuild and revivify Sandtown, and examined the perverse role played by the internet and social media in cheering on violent gang behavior.

Perhaps the most important discovery was that Barronette and his TTG crew were not, as prosecutors and cops suggested, outliers or dangerous psychopaths. They were essentially normal teenagers in an abnormal environment, one that Baltimore (and other cities) had built and sustained very deliberately over centuries. TTG was perfectly adapted to its habitat. To better understand that story, I read a wider range of books and papers, and interviewed more academic experts, than for any other book I have written. Relevant parts of that research and reporting are cited throughout in the text and in source notes.

Ultimately, this isn’t a story about an unusual group of young men. It is the story of young men growing up in a place where murderous violence has become a way of life.

1

The Game(or, The Greased Path)

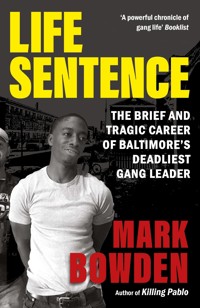

Tana with his siblings: left, Shanika, and right, Rell.

Violence becomes a homing pigeon floating through the ghettos seeking a black brain in which to roost for a season.

—Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice

When he was a boy, his mother briefly removed him and his baby sister from the apartment in Sandtown where they lived with their grandmother and two older half siblings.

His mother, Annette Burch, brought them to the Poe Homes, a notorious West Baltimore housing project. This would have been in about 2002, when the boy, Montana Barronette, was seven, and his little sister, Sahantana Williams, whom the family called Booda, was two. Less than a mile away, it would have been a sharp change for the children. It took them “over the bridge,” south of the sunken, divided Franklin-Mulberry Expressway (US Route 40), a roaring moat that formed the bottom of the world they knew.

The area over the bridge had been long defined by the brick towers of the Lexington Terrace housing projects. Built in the 1950s, in part to house those dislocated by the beginnings of Baltimore’s massive modern downtown renewal, the five eleven-story towers were a universally acknowledged disaster. In them were all the ills of the urban poor, compressed. One resident described them as “a living hell.” After the buildings were imploded in 1996, their occupants were resettled in the Poe Homes, rows of squat red-brick town houses that filled roughly three large square blocks. This did not resolve the problems of the towers, just spread them horizontally. The neighborhood remained virtually all Black, poor, beset with violence, and a central hub for heroin distribution—a small step down from Sandtown, which was all those things, too.

The removal of Montana and Booda must have seemed a blessing to Annette’s mother, Delores, and might have come at her insistence. All four of the children were Annette’s. Delores had taken them into her Harlem Avenue apartment one by one, after raising her own brood of five. She worked full-time as a custodian at Baltimore City Hall and had no help from her estranged husband. Annette was always nearby, adrift in the circle of neighborhood drug users, shifting for herself. Eventually her fifth child, James, would come to live with Delores, too. The fathers of these children were truant.

Mother and grandmother were opposite extremes, Annette dissolute, Delores pious and stern. Delores belonged to a local Pentecostal church, and as her daughter delivered child after child, she was trapped by her own sense of responsibility. The children could not be abandoned, or blamed for the sins of their mother or fathers. They had to be taken in, even if this enabled Annette’s behavior. So Terrell and Shanika Sivells, Montana Barronette, and Booda and then James Williams were reared on their grandmother’s sometimes bitter forbearance. They were not mistreated but felt the bitterness. Because their mother was around, they were caught in a contradiction. At home, Delores dragged them with her to worship so often the neighborhood kids taunted them, calling them “church kids,” which they hated. But work kept Delores away often, so they spent a lot of time in the streets with their mother, learning the ins and outs of the corner drug markets. This left them always out of step, teased on the corners, an enemy camp in the Harlem Avenue apartment. “We all went through our own separate hell when we was kids,” Shanika would say years later. Annette’s decision to take the two youngest with her to Poe Homes may have resulted from an ultimatum or perhaps a fleeting good intention. Whatever the reason, it didn’t last.

One morning, not long after the move, the children woke up alone. Montana waited all day, until nightfall, and when their mother failed to return, he left with Booda and flagged down a police car. The officer took them back to Harlem Avenue.

Several things of note about this: It shows the tenor of his upbringing. It shows him to have been poised and capable at age seven. And it also shows him to have been unafraid of the police.

Given the stories told by his older sister, this last is surprising. Shanika grew up in terror of cops. In particular, she remembered a night when police crashed into their apartment, guns drawn, looking for Montana’s father, Delroy. Montana was then an infant, named after a paternal Jamaican uncle. Shanika was only three, so her memory is mostly secondhand and probably exaggerated, but there is no doubt that the raid was traumatic. Delroy wasn’t there. Annette was nabbed trying to climb out a back window and was taken away. Seeing their mother arrested would be enough to sear the night in the children’s memory. For the rest of her childhood, Shanika would blame the raid for her nervous problems and nightmares. Ever after, Delores would shake and pray when she heard a siren. Shanika firmly believed that the police, local and federal, had a vendetta against her family. Delores would say, simply, “I just don’t like them.”

Yet Montana, at seven, abandoned in a strange place with his baby sister, sought out a cop.

He would have had no memory of the raid. The only police he knew were kindly ones who bought treats at the corner store for neighborhood kids. Montana would sometimes go with other children to the precinct station and beg. For a long time after being abandoned at Poe Homes, he would say that when he grew up, he wanted to be a cop.

It was a dream not destined to last. In Sandtown, cops were seen less as protectors than as an occupying force. The neighborhood might as well have been an adjunct to the Maryland prison system, so many of its men were either locked up or enjoying a brief taste of freedom between jail terms. The neighborhood had the highest incarceration rate not just in Baltimore but in all of Maryland. Nearly everybody knew or loved somebody who had been jailed at one point or another or had been locked up themselves. Like most people convicted of crimes, few felt their punishment was just. Most in the community distrusted police and judges, a rational apprehension with deep historical roots. Such places are a breeding ground for criminals. Writing in an era of lynching and overt Jim Crow restrictions, sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois had noted this more than a century earlier, observing oppressed Black communities in the rural South.

The appearance, therefore, of the Negro criminal was a phenomenon to be awaited; and while it causes anxiety, it should not occasion surprise. . . . When, now, the real Negro criminal appeared, and instead of petty stealing and vagrancy we began to have highway robbery, burglary, murder, and rape, there was a curious effect on both sides the color-line: the Negroes refused to believe the evidence of white witnesses or the fairness of white juries, so that the greatest deterrent to crime, the public opinion of one’s own social caste, was lost, the criminal was looked upon as crucified rather than hanged. On the other hand, the whites, used to being careless as to the guilt or innocence of accused Negroes, were swept in moments of passion beyond law, reason, and decency. Such a situation is bound to increase crime, and has increased it.

For various reasons, Montana’s immediate family had fallen into a condition of petty crime familiar to Sandtown. Delroy was arrested three times in the 1990s. He served at least one prison term and was deported to Jamaica when his son was four. Annette had her share of arrests, and out on the streets she schooled her children in The Game, the ongoing hustle of selling illegal drugs, learning how to work street buys and avoid those who would steal from them or arrest them— sometimes one and the same.

Montana Malik Barronette was born in 1995 in the richest country in the world. Yet by virtue of his race and gender, statistically speaking, he had from his first breath a much smaller chance than most American children of reaching adulthood alive, avoiding prison, or enjoying even modest legitimate success—a college education, say, or a steady job. If he failed to finish high school, he stood a less than fifty-fifty chance of holding a full-time job by the time he was thirty—for white Americans the chances were close to 90 percent. If he did everything right, finished high school or even college and found employment, he would likely earn 20 percent less than a white man. The poverty of Montana’s family alone would drag him down, but so would his race—a white child born into a similar situation was three times more likely to escape it. The community around him further reduced his chances; there were few examples of legitimate success and many of failure. In this, he was no different from many other Black American children, particularly those from blighted urban districts and, in Baltimore, even more particularly those from Sandtown. Writing about the neighborhood in his book Black Baltimore, published two years before Montana was born, author Harold A. McDougall noted that, in the “virtually all black” district, “unemployment is high, and there are a significant number of female-headed households living at or below the poverty line,” and its overall crime rate was the highest in West Baltimore.

Statistics are not destiny, of course, and there are many things that can and do help defeat those odds—good parenting, a strong family and community, good schooling, role models, opportunity, and, not the least, character. Most Black children, by far, do defeat those odds, even those from Sandtown. They not only survive their youth; they avoid the pitfalls on their path and thrive. Kurt Schmoke, the former mayor, estimates that in every high school homeroom class in Baltimore, there is likely one child fully lost to street life. “But in a large school,” he says, “that becomes a big number.” Without any of the advantages listed above, a child’s character, the crucial check on criminal behavior, is strongly tested well before maturity has armed him to resist.

Montana had no advantages. Born poor, he grew up mostly fending for himself. Parents? Selling and using drugs was the family way, one that had brought little beyond misery. Father exiled to Jamaica, mother somewhere in the neighborhood doing her thing. Community? With drug markets openly working the corners, addiction and violence were rampant. There were other hazards. Living in a rundown old town house on Harlem Avenue, the children had a strong chance of being exposed to mentally debilitating lead paint—an enormous problem in Baltimore’s poorest neighborhoods. Schools? Harlem Park, the grade school Montana attended, was consistently ranked one of the worst in the state. Opportunity? When he was old enough to look for work, if he chose to look, competition was fierce for the few legitimate jobs, most of which paid only minimum wage.

On the corners, by contrast, The Game paid handsomely.

The pull was gravitational. Montana’s path was greased. He was, Shanika would recall, “the baby on the block,” running errands for those working the corners, who ridiculed his fondness for the police. Concerned adults, especially late at night, would stop to question him or his siblings. Who did they belong to? What were they doing out by themselves? Montana was a fast learner. Soon he was selling drugs and committing bolder crimes. At nine he was arrested for stealing a car. The police, no longer his friends, took an arrest photo. It shows a frightened slender boy with dark skin, short hair, ears poking out of his small head, big eyes under worried raised brows. He looks younger even than nine, weighing in at all of sixty-five pounds and barely tall enough to see over a steering wheel. By then the street had him.

He was already working for one of the local heroin dealers, Davon Robinson, selling a product labeled “Get Right.” It was a complex operation. In little processing and packaging shops, the heroin was cut with any number of white powders—quinine, powdered caffeine, chalk, baking soda, mannitol, crushed pain pills, a substance known as “benita” (said to be “baby laxative”), and so on—reducing the kick but stretching the product and upping the profit. It was delicately apportioned and sealed in gelcaps, which were sold in packs of twenty-five or fifty. The “corner men” directed traffic, dealt with buyers as they drove or walked up, and took their money. Since they were the most visible of the drug shop’s workers, out in the open all day and night, they never handled the drugs. A “pack runner” was dispatched to report the sale. The drugs were delivered by “hitters” from the hidden stash—usually in a nearby vacant house—to the buyer. Since this was the overtly criminal part of the exchange, hitters were often the crew’s youngest members, who, if arrested, would be charged as juveniles. Both Montana and his half brother Terrell started out as hitters. Industrious and smart, they were soon running their own shop.

When the boys peddled their own product as “Get Right,” Robin-son complained, and they changed the name to “True Bomb.” Besides heroin, they sold fentanyl, cocaine, marijuana, and Percocet, Xanax, and other pills.

Very soon they were making good money. They were Tana and Rell, familiar and feared, players in The Game, part of a strutting, darkly fatalistic street subculture with its own hip style, language, and music. The dead-end nature of the enterprise was part of its attraction. Disputes over status and turf were routinely settled with handguns, readily obtained. This was not, as we tend to think of outlaw behavior, rebellious. Tana simply embraced what he found. Children adapt readily to their environment. His world had been violent from the start, from the beatings meted out by his frustrated grandmother when he misbehaved to those delivered by bullies on the street. And beatings were the least of it. Children in Sandtown learned early to duck and run for cover at the sharp pop of gunfire. They were accustomed to seeing the oily pool of blood on the sidewalk under a victim, its oddly metallic odor, and the sight of spilled viscera or brains. These were not singular traumatic events but as ordinary as ice cream trucks tootling down suburban streets. They were also formative, particularly when the victim was a relative or friend, altering normal expectations for a long life. Fatalism came naturally.

As did contempt for the police. The brothers’ rise as Sandtown street dealers coincided with a complete breakdown of law enforcement in Baltimore. The divide between Black communities and police was a given, rooted in a long history of racial injustice and insensitivity, but in Baltimore it was aggravated by the force’s futility. Getting away with murder was routine. Citywide, the homicide clearance rate—just arrests, not convictions—was less than one-third, and it was far worse in Black neighborhoods. In 2015, the year Tana and Rell were in full stride, there were sixty-four killings in the Western District, the Baltimore Police Department division comprising Sandtown and several other neighborhoods. By the end of that year, only eighteen culprits had been charged—less than half the citywide rate. This both encouraged shootings and severely discouraged witnesses from helping the cops. Often the killers were well known, but so long as they remained at large, it meant talking to the police—snitching— wasn’t just pointless, it was dangerous. So ordinary citizens turned their heads, which, as many cops saw it, made the community itself complicit. Any tenuous bridges between police and community collapsed in April 2015, when a Black twenty-five-year-old named Freddie Gray was arrested in Sandtown and suffered injuries in a police van on the way to lockup that resulted in his death a week later. The arresting cops were accused of first injuring Gray’s back and then taking him for a fatally rough ride, unsecured in the back of their vehicle. Protests flamed into riots. Failed attempts to prosecute the arresting officers fed the anger.

And when the mayhem subsided, the police, stung by community antagonism and outraged by efforts to prosecute their brethren, effectively stopped policing Sandtown and other Black neighborhoods. This, predictably, fed still more violence. In a lawless place, people seek their own justice. Shooting or robbery victims exacted their own revenge or were avenged by family and friends. Gun violence took off like a runaway chain reaction. In the first half of the decade the number of murders citywide annually was about 200; in 2015 it was 344, and totals in following years stayed in that vicinity. Sandtown and neighborhoods like it had slipped out of control. All of this would lead to a federal takeover of the city police department in 2017.

This calamitous descent was, for the most part, extraneous to Baltimore’s wider white community, where violence was rare and law enforcement more diligent, efficient, and respected. For suburbanites and those whites living in the city’s most affluent areas, like nearby Bolton Hill, Roland Park, or Guilford, the shootings were a Black thing. This racist assumption formed an inferential loop: if one assumed violence was common in Sandtown because Black people lived there, the more violent it became, the more the assumption seemed true. It had always been thus.

Sandtown was a particularly egregious example, but Baltimore was not the only city plagued by gun violence in Black neighborhoods. During the first eighteen years of the twenty-first century, about 162,000 Black people were murdered in America, notes sociologist Elliott Currie in his 2020 book A Peculiar Indifference, citing figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Black men between the ages of fifteen and twenty-nine made up more than half of that number. A young Black man has sixteen times the chances of dying from violence as his white counterpart—this in a country whose young white men are, according to Currie, five times more likely to be murdered than young German men and twenty times more likely than young Japanese men. Somehow this is not, and never has been, considered a big deal in white America. On New Year’s Day in 2022, Amy Goldberg, a veteran trauma surgeon at Philadelphia’s Temple University Hospital, after treating twelve shooting victims, two of whom died, tweeted, “Where is the outrage . . . from everyone?” In an interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer, she explained, “I was just so angry, as we all should be. The number of homicides are outrageous, more than ever. I just couldn’t understand. We need to be moved. What’s it going to take [for] us to be moved to do something?”

But doing something about Black on Black violence has never been a social priority. The epidemic of violent death in Black communities is rarely even mentioned by political candidates, other than those running in afflicted localities. Newspapers and local media typically ignore all but the most shocking incidents. The shooting and killing has become, simply, urban background noise, shrugged off as thugs preying on thugs or, to put a finer point on it, Blacks preying on Blacks. Even though social scientists, beginning with Du Bois, have roundly debunked the idea that Blacks are inherently more violent than whites, this myth is widely, if not always consciously, accepted by whites who do not consider themselves racist, for the same reason that most whites do not see racism in the hugely disproportionate percentage of Black people behind bars. I can remember my grandfather, as we drove through a Black neighborhood in Chicago in the 1950s, telling my brothers and me, “Roll up your windows and lock the car doors. These people are dangerous.” He didn’t use the word “people.” In my early years as a reporter in Philadelphia, I remember asking my white city editor why we weren’t writing more stories about the murders happening in the city every night. “It’s not news,” he said, flatly. “Those people are always killing each other.” It goes without saying that the violent deaths of 162,000 whites would not be background noise.

In the worst afflicted neighborhoods, murder and maiming by gunfire are so much a fact of life that they have spawned an aberrant subculture. Exiled in their own cities, Black Americans by necessity had always formed separate local societies. In some cities, Baltimore included, these produced a flowering of discrete music, dance, painting, and literature in the early twentieth century. But they also produced a criminal class regarded, as Du Bois pointed out, with a measure of sympathy, if not esteem, by the very communities it preyed upon.

Today, those young Black men who drift away from school— Schmoke’s one child per homeroom class—compete for status and success on their neighborhood corners. They war ferociously. In Baltimore, city police have identified 320 distinct local gangs. For each, The Game is lethally serious. Where death is normalized, life is cheapened, especially when it is so little noted by the larger world. Centuries of that disinterest, along with social and economic isolation, have bred violent cultism in places like Sandtown. One of the consequences of being relegated to the lowest caste, Du Bois noted, was “recklessness.” This was certainly true for Tana. Discarded by society—in his case by his own family—he embraced his dead-end status, living fast and expecting to die young or to face long imprisonment—which was actually less likely than being felled by a bullet. Who cared? What did it matter? And if his own life meant so little, how much did anyone else’s matter?

Delores was overmatched as Annette’s children reached their teens. “She was frustrated because she needed help,” says Shanika, who as a child chafed under her grandmother’s authority, but who would have sympathy for her as a grown woman and a mother herself. Growing up in the twenty-first century, she and Terrell and Montana spurned Delores’s old-fashioned and religious ways. The street offered more immediate and tangible rewards. If they saw things they wanted on TV or in movies, or things other children had, the answer at home was always, “Y’all got to learn how to make your own money.” So they did. When she was twelve, Shanika once made $100 in one day selling drugs. Terrell, a year older and male, did better than that. Boys were more prized than girls for the street hustle. Girls, as Shanika would learn soon enough, were prized for other things.

As long as she could, Delores stayed in the fight. She found summer jobs for Terrell and Shanika. But the demands of real work, and the low pay, couldn’t compete. Shanika was soon drinking alcohol and using some of the drugs she sold. She and Terrell stopped going to school. Shanika was thrown out of the apartment when she was fifteen. Terrell went soon after. They moved across the bridge to stay with their mother. Montana, who looked up to them, especially to Terrell, followed a few years later, around the time Shanika got pregnant, and Delores relented and let her return home until she gave birth.

By 2012, it was just the brothers on the streets hustling. They became notorious. With its outsize stakes, The Game bestowed not just status but glamour. Even suburban white boys adopted Black street lingo and fashion and consumed rap music and videos that celebrated “gangsta” life. Authenticity was prized above all. A rapper might pretend to have street cred and might even enjoy a bump in sales if he was arrested, but Tana and Rell were the real thing. Their business, which in time they chose as much as it chose them, was not just accepted by their family and friends, it was embraced.

For the brothers, homelessness was no hardship. It suited them not to have a fixed address. Escaping the Harlem Avenue apartment meant escaping Delores’s disapproval, the last vestige of adult control. They thrived. It was the one avenue for which they had an advantage, having entered The Game when most children were still being sent to bed early. They had money. They roved from place to place, staying with friends. They were popular, admired. They got high and drank and, soon enough, were having sex, often with multiple girlfriends. Tana would father a son and daughter by two different women, Rell three daughters. They were living a teenage dream. To rise above this, Tana would have to have been extraordinary. As it happened, he would prove himself extraordinary not by transcending The Game but by mastering it.

Danger was a big part of the allure. One way to achieve status, especially for the young, is to tempt fate, the more recklessly, the better. For most teens, in most places, the penalty for such behavior might mean a broken bone, a bad hangover, perhaps the occasional misdemeanor arrest. In Sandtown the risk was mortal—which upped the status points accordingly. Street rules made more intuitive sense than Delores’s Christianity. The street blessed the bold, not the meek. Someone slaps you, slap back harder. It was about building a hard rep, never backing down, and commanding respect.

There was even a righteous rationale for it. Americans—of every race and social class—craved narcotics. They had to come from somewhere. While suburbanites were not getting busted for recreational drugs stashed in bedroom drawers, those who sold it to them were going to jail. The laws were baldly hypocritical. This was particularly true in Sandtown, where some of the very cops who busted corner crews and seized their product turned around and sold it. When you looked at the hugely disproportionate number of Africans American locked up on drug charges, it was easy to see the whole multibillion-dollar incarceration industry as just the latest face of a time-honored American project, Keeping the Black Man Down. Trapped in the worst neighborhoods with bad schools and few employment opportunities, viewing the relative affluence of the larger white society, it was easy to react with reckless anger and defiance. Du Bois would write, in The Philadelphia Negro: “How long can a city say to part of its citizens, ‘It is useless to work; it is fruitless to deserve well of men; education will gain you nothing but disappointment and humiliation’? How long can a city teach its black children that the road to success is to have a white face? How long can a city do this and escape the inevitable penalty?” The penalty is street crime and violence. Hustling drugs, making money, enjoying the illicit pleasures of the life was a way to get back, to raise a middle finger to injustice. It was the price Baltimore paid for centuries of inequity. As for Tana, he was all in. Prison or an early grave? “Fuck all you anyway!”

Everybody could see that Tana, in particular, was smart. He was also likable, genial, even goofy, singing, cooing his little raps, teasing—his sister thought he could be a real pain in the ass. Rell was often stoned, so spacey and slow that people wondered whether he was all there. On the street, people called him “Smiles.” But if older brother was all about maintaining a pleasant buzz, little brother had plans.

His ambition showed in unexpected ways. Even as his earnings and rep grew in the street, Tana carefully preserved his options. Without Delores or anyone else to rouse him up in the morning and point him out the door, and despite the examples of his dropout father, mother, older brother and sister, and most of his friends, Tana continued to show up at Edmondson-Westside High School. He played football and basketball and did well enough to graduate, in 2013—the first person in the family to, as Shanika put it, “walk across that stage.” He told his sister that he was also going to break their family’s cycle of poverty and ruin, and that he wanted to be an example to other kids, to show them, he said, “that they don’t have to be a street nigger.” He applied for a program with State Farm that would train him to drive big trucks, steady work that paid well and came without gunplay—a calm, respectable life with middle-class comforts. So even as he was building his street rep, he preserved this option—another path—of becoming a “worker,” the word in Sandtown for those who earned an honest living. Workers were regarded with a mix of pity and respect. You could admire the decency of those who shunned The Game, but for most it led only to a low-wage treadmill of drudge work and dashed hopes. So many things stood in the way of greater legitimate success. In 2015, the year Tana turned twenty, Harvard University researchers ranked one hundred American communities by how easy it was for a child born into poverty to escape. Baltimore placed dead last. Still, Tana kept that chance alive. His acceptance to the trucking program arrived in the mail just days after his own fate was settled for good.

But for him The Game was irresistible. For that he had role models aplenty, like Pony Head, Jan Gray, the reigning corner king in Sand-town, with his new sneakers, gold chains, steamy girlfriends, and the fine leather wallet that swung from a chain on his hip.

2

Shabangbang Shaboing

Pony Head’s mug shot.

All my niggas TTG, they Trained to Go, shawty . . .

I got a O-40, wit’ like four bodies on it

Twerk, puttin’ niggas in the dirt

Enemies necessary, make her work . . .

Trained to go, shawty

—Waka Flocka Flame, “TTG,” Flockaveli

It took Pony Head a long time to realize that The Game—his game—had changed. And in a very bad way.

The big clue he missed came on the night of May 4, 2014, a pleasantly cool Sunday under the streetlamps at the corner of North Carey Street and Harlem Avenue, when he exchanged taunts with that nineteen-year-old upstart Tana.

Carey and Harlem form a particularly wide intersection because traffic slows where Harlem, running east–west, halts at Carey and then resumes a half block south. The jog divides the neighborhood row houses into full and half-block segments, punctuated by open lots, and creates something like a neighborhood square. People were out, sitting on steps along the sidewalk. There was a pleasant hum of talk and laughter, the air scented with cigarettes and the dusky aroma of weed. Pony Head was in the mix, as usual, keeping an eye on business. This was his world, his neighborhood. He was in the lap of family, friends, money, and women. In this little quarter of West Baltimore, Pony ruled.

It was a dubious distinction. Sandtown, a roughly triangular tract of seventy-two row-house blocks amid Baltimore’s larger urban sprawl, was like a sore that would not heal: block after block of row houses in rampant decay, vacant three-story structures with fronts encrusted in years of grime, with peeling paint and faded Formstone, doors and windows either empty or covered with warped, gray plywood, once proud marble stoops stained black, worn at the center from a million footfalls. Gravity, doing its relentless work, was pulling some of them in on themselves. Others leaned toward the street, buttressed with four-by-fours anchored to the sidewalk. Nature was also doing its part. Determined scrubby bushes and even small trees sprouted wild—no doubt from seeds shat out by birds—from open windows and rooftops. Tenacious wall-eating vines clung to facades. Beneath the weeds on empty lots lurked rusted junk, trash, litter, garbage, tires, and other urban detritus. From pockets of packed earth along the sidewalks stood obstinate small maple and ginkgo trees, budding green now like some sad memory of spring. In a month the weeds around them would be waist-high. Here and there were clean rebuilt blocks, evidence of fitful attempts at renewal, and some walls were adorned with colorful murals bearing themes of African American pride. These stood out jarringly from the surrounding rot. It was easy to imagine those living here, growing up here, feeling like social discards, which they were.

It was also surprisingly roomy for a ghetto. This was partly because so many houses had been demolished, creating open lots, and partly because the wide streets had been built to accommodate traffic from the western suburbs. Views from intersections were particularly broad. To the southwest, just a dozen or so blocks away, was the Baltimore skyline, a cluster of towers, old and new, that spoke of power and money, the white city center—just over there—both near and far. Its proximity, if anything, underscored the sense of isolation and neglect.

Such was Pony Head’s unlovely turf. Sandtown was all that the larger city did not wish to be. Baltimore had plenty to boast about. Roughly six decades after the city began rebuilding its dilapidated core, transforming its distinctive Inner Harbor into a tourist destination—hotels, museums, new sports stadiums, restaurants, and glitzy entertainment centers that attracted millions annually—Sandtown remained what it had long been: poor, drug-infested, and violent. With a murder rate that ranked it consistently among the deadliest neighborhoods in the world, this was the side of Baltimore made notorious by the revered HBO TV series The Wire, the part that had earned the city its nickname “Bodymore, Murderland.” One of the city’s oldest Black neighborhoods, Sandtown was by almost any measure the worst. It was named for the spillage from horse-drawn wagons hauling loads from a sand quarry at its western edge in the nineteenth century, creating small drifts in the streets and sifting into kitchens, living rooms, and cellars. Now the sand was gone, but the neighborhood was famous for something else: it was exhibit A of intractable urban failure, a negative of the dazzling new image Baltimore strove to project.

For Pony Head, it was just home. He had grown up here, on the same block of Carey where he now sat. We picture cities as monumental gray blots on the landscape, but they are actually mosaics, patchworks of hundreds of distinct neighborhoods, each as blinkered as a small town. Sandtown, for all its dangers and faults, was still a community. For those rooted here, it was comfortably familiar, in the true sense of the word, a place of family and friends, of shared history and experience. Anger and violence, poverty and hopelessness were part of it, but life here was not all grim. The streets, for those who belonged, could be lively and fun. And for many, for those like Pony Head, Sandtown’s very infamy was a source of perverse pride.

If you could make it here . . .

And Pony Head wasn’t just making it, he was thriving. A thickset, confident, genial man, his light brown skin flecked with tiny moles around his eyes, he was prosperous and content. His birth name was Jan Gray. As boys, he and his buddies made silly chalk drawings of each other on the sidewalk, just up the street. One produced a crude sketch of Jan as a pony, exaggerating his pronounced noggin—he’d always had a high forehead—and he became Pony Head. At thirty-nine, still with a tall cranium and now with a dense black beard that sometimes reached his chest, the name seemed even more apt. More people knew him as Pony Head, or Pony, than by his real name.

Everybody who engaged in the street life of Sandtown had a nickname. It certified that they belonged and might also help shield their legal identity from hazards like bill collectors and the law. Pony sold drugs, mostly heroin and grass, as had his father before him, until he was murdered. Pony joined The Game when he was still in grade school, working as a gofer and a lookout for corner crews. It was both lucrative and fun. There were more benefits as he grew older. Girls swooned for him. The mix of drugs and money and guns was irresistible. After many years of hard and dangerous effort, the neighborhood corners were his.

His domain was two blocks wide, between Calhoun Street on the west and Carrollton Avenue on the east, reaching north to Mosher Street. The southern border was Edmondson Avenue, one block south from where he now sat. His territory bordered two small parks, Harlem Square and Lafayette Square. This thin rectangle, five blocks long, was prize drug turf. More than once Pony and his crew had had to defend it. He oversaw the cutting, packaging, and distribution— in small glass vials with red plastic caps—of a popular heroin brand he’d named “Sweet Dreams.” Fifty vials per pack, a dollar each. It was a hot product. Pony’s corners were open seven days a week, from seven in the morning until seven at night. White kids would drive up from South Baltimore and buy fifty packs at once, dropping $2,500. Say what you will about addicts, they make steady customers. On an average workday, Pony Head and his crew, what he called his “little clique,” would pull in a predictable $10,000, and on good days, twice that. Not that he was personally pocketing that much. Most of the take went for re-up, to pay his workers—each earned fifty dollars a day—and to cover losses.

Losses were a bitch. There were so many ways to lose product and money that it took formidable management skills to turn a profit. One of the features of any illicit trade is the need for self-protection. When people steal from you—your rivals, your own people, others—you are on your own. If you can’t defend your corners, you are out of business. Pony did not regard himself as a violent man, but he did what he had to do.

There were also perils completely outside his control. Some of the worst thieves he contended with were city police. One of the department’s busiest, most in-your-face street units during Pony’s big years was the SES (Special Enforcement Section), which had a star squad called the Gun Trace Task Force. It was created to do smart, aggressive policing, targeting the city’s most violent actors, confiscating their weapons, and using the amazing tools of computer-assisted ballistic analysis to connect them to specific crimes. What it became instead was an organized crime unit, not in the traditional law enforcement sense but in the purely criminal sense. The Gun Trace squad was a gang with badges, whose members preyed upon dealers and convinced themselves—even as they enriched themselves—that they were doing God’s work. If you were doing good, the logic went, who would begrudge you a healthy cut? Beyond straight-up theft, they broke into cars and houses, invented charges to justify searches, faked videos to establish alibis, and robbed dealers—or alleged dealers. And this unit was not just tolerated on Baltimore’s force, it was praised, albeit mostly by itself. Wayne Jenkins, its commanding sergeant, and his men regularly posted photos posing before captured money and guns, boasting of their accomplishments. This was particularly galling to those on the force who knew that few of the unit’s cases resulted in convictions. More often they fell apart in court, as judges ruled its reports and testimony unreliable. Well before fellow officers learned of the unit’s illicit activities, many city cops were skeptical of its methods and disgusted by its grandstanding. Nevertheless, those who spoke critically of the squad were met with ridicule. “You were just accused of being jealous,” said one detective. It amounted eventually to a yearslong departmental charade, with Jenkins leading the cheers for himself. He and other leaders of the outfit were decorated and promoted. If fellow officers were deterred from calling them out, which of their victims dared to report their crimes? And to whom?

So, like every dealer in the city, Pony kept his product hidden. He had a lot of hiding places and shifted them constantly, which, inevitably, led to more losses. An entire shipment once vanished from a rooftop hiding place. Who had taken it? One of his own workers? A random civilian who had stumbled on it? The cops?

Then there were the honest cops, a different brand of trouble, busting him or his crew, keeping their arrest numbers up. One day Pony was nabbed carrying almost $2,000-worth of product. That was immediately lost. Add in attorney fees to defend himself, and the financial hit ended up being more painful than the prison stretch. He could afford a good lawyer, and while he had been to jail seven or eight times for possession with intent to distribute, and once for assault, he had always managed to dodge what he considered a serious charge. All of this, too, was part of The Game.

So, being the corner king in Sandtown was a mixed achievement. Pony had his struggles, but he still made plenty. And it was enjoyable, especially the social aspect. Friends everywhere. Little kids would follow him up the sidewalk, cadging for quarters or dollar bills. He was generous and shared liberally with his very large family—he counted eighty cousins in all. It was amazing how they turned up when he was flush. He had a steady woman with expensive tastes, and he liked to show a little flash himself: pristine designer sneakers, necklaces, watches, rings, and chains. He had a long gold chain he suspended from his belt, from which hung one of the fancy wallets from his collection. He projected prosperity and calm authority. His voice, graveled by cigarettes, was usually low. Here, in the hardest of neighborhoods, Pony Head, who had left school after eighth grade, was that most American of success stories, the entirely self-made man.

His friends and family did not consider him a criminal. The Game was just a fact of life. Pony had simply risen to the top, taking advantage of a clear and present opportunity in a place where opportunity was scarce. In time, a successful corner king could even acquire a measure of security. If you stood your ground long enough, and were bold and lucky enough, as Pony had been, you earned a rep sufficient to back off the competition. Even your respectable neighbors tolerated you somewhat, so long as the shooting incidents were kept to a minimum. This was one of the arenas—community relations—in which Pony excelled. He cultivated goodwill, but he could also project quiet menace. He was loath to do it, but various neighborhood improvement efforts over the years had caused him headaches. For instance, an entire block of Carey Street, right across from where he sat that night in May, had been renovated. The rebuilt houses looked fabulous, like new, with warm red-brick facades, bright white trim around new windows, marble stoops scrubbed clean. The block looked like an ad for urban renewal, with spiffy, appealing homes on one side of the street and decayed ruins on the other. Into the fresh, newly refurbished side of the street had moved respectable, middle-class homeowners. Pony was good with that—until they started calling the cops on his crew working across the street. He spread the word that unless this stopped, some of the fine cars his new upscale neighbors parked before their fine homes might start catching fire, which would be a terrible shame. The calls stopped.

This was mild stuff, easily managed. Pony was no one to trifle with, but he was also amiable. People liked him. He had achieved something like tenure. He felt so firmly ensconced that he believed any threat to him would be countered not just by his crew but by the whole community. Sandtown looked after its own.

This is one of the reasons the warning hurled his way that May evening, as he sat literally minding his own business, didn’t register.

It came from Tana, walking past jauntily. Pony knew and liked him, a wiry, very dark-skinned teen with a loping stride, a homeboy. He had watched Tana grow up, one of the kids on the block who had sometimes followed him around in years past. Pony had gone to school with his mother, Annette, and had even hung around with her a little before she began, as he put it, “dibbing and dabbing” in the product. He had known Tana’s father, a big jovial Jamaican dude, before he got arrested and deported back home. He knew churchgoing Delores, and that Tana had been mocked as a “church kid.” Pony had admired how the boy, even when very small, had always held his own out on the block, cheerful and smart, with a quiet dignity that belied his situation. Proud. Surprisingly poised. Always dribbling a basketball. In his school years Tana had often sat with Pony in the mornings before shouldering his backpack and heading off to classes, and then returned in the afternoons. The kid was the same age as some of Pony Head’s own. Pony had an avuncular feeling for him.

But now the kid had developed swagger, especially since his older half brother, Rell, had been busted and sent away. Tana had assumed leadership of their little drug operation. They were calling themselves “TTG,” for “Trained to Go.” Tana wore wide, loose, low-slung jeans and tight T-shirts that showed off his slender torso. He wore gold caps over his front teeth so his smile gleamed like the grillwork of a luxury car. His face had matured, acquiring overlarge features—big, heavy-lidded, bulging eyes and a long, sloping, wide nose, the tip of which fell just short of his full lips. A receding chin exaggerated those jutting features, giving him an exotic face to match his exotic name.

Tana came up the sidewalk with a phone held to one ear, bobbing to some internal beat, and called out, “Pony, you ain’t from around here no more. You washed up.” He was laughing.

Pony jabbed back in the same spirit: “Yo, this is my block. Yeah. How many times I’m gonna tell you that, yo? This seven hundred Carey Street is me, dog. All the way down to Edmondson Avenue, yo.”

This was “the dozens,” good, harmless neighborhood fun. Tana kept at him.

“Cuz, yo, I shouldn’t see your name on nothin’ else around here,” he said, still with the phone to his ear, still smiling. “Flat out. I mean, we ain’t gonna have this talk no more. Next time I’ll just bang you, like, shabangbang shaboing.”

Pony scoffed.

Tana added, “Crack your head.”

“I mean, why the fuck you be rubbin’ on my arms, yo?” Pony protested, laughing.

Then Tana moved off, still talking into the phone. Pony thought nothing of it. Young ’un strutting his stuff on a Sunday night.

Tana and Rell sold a heroin brand called “Checkmate.” This didn’t concern Pony. Demand was bottomless. When you put more heroin on the street, more buyers showed up. He had let it be known, however, that he expected a cut from anyone peddling on his corners. This he considered only fair. He had secured the turf. It had not come free, so why should sharing it be free? So while he expected a fee, he did not consider Tana and Rell competition. And even if he were, Rell, whom Pony considered the more menacing of the brothers, was locked up. Tana was just a nice kid.

He didn’t give the exchange a second thought until a month later, when, on his way to a corner store, a little homeboy named Tev, Tevin Haygood, one of Tana’s TTG crew, stepped out of an alley across the street and fired two shots at him. Both missed. Luckily, the boy hadn’t dared come close enough to make them count. Tev was another one Pony had watched grow up—cute kid, was how he saw him—but like Tana, he’d grown into a cocky teen. They had exchanged words a few days earlier, Tev acting like a hard case, boasting of being a “shooter,” and Pony dissing him, telling him to knock it off. The shots, Pony figured, were just Tev’s wounded pride. Unless . . . unless it had something to do with Tana’s challenge? Had the kid acted on Tana’s orders? Pony wondered about it and dismissed it, which says something about his world, where being shot at was a thing anyone could dismiss. As he saw it, the attempt, however outrageous, had been timid and halfassed. Having made his point, Tev would not likely try again or, for that matter, cross his path anytime soon. Pony was a serious player. Nobody had gotten hurt, yet. He chalked it up to teenage bluster.